Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Kohlhammer

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

The distinctiveness of this commentary lies in its consistent rotation between synchronic and diachronic views. This double perspective is directed toward the three prophetic books as a single entity, toward each individual book, and toward the interpretation of each pericope. The result is a sophisticated picture, on the one hand of the structure and intention of the texts in their final form, and on the other hand of their compositional history - from the second half of the 7th century to the late Old Testament period. Each exegetical section opens with a precise, text-critically supported translation and finishes with a synthesis that attempts to make note of the lasting insights from each text and the most important results of the analysis.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 750

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

International Exegetical Commentary on the Old Testament (IECOT)

Edited by

Walter Dietrich, David M. Carr, Adele Berlin, Erhard Blum, Irmtraud Fischer, Shimon Gesundheit, Walter Groß, Gary Knoppers, Bernard M. Levinson, Ed Noort, Helmut Utzschneider, Beate Ego

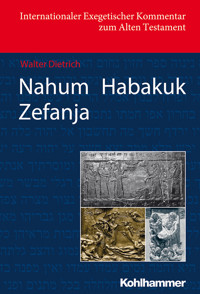

Cover:

Top: Panel from a four-part relief on the “Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III” (859–824 BCE) depicting the Israelite king Jehu (845–817 BCE; 2 Kings 9f) paying obeisance to the Assyrian “King of Kings.” The vassal has thrown himself to the ground in front of his overlord. Royal servants are standing behind the Assyrian king whereas Assyrian officers are standing behind Jehu. The remaining picture panels portray thirteen Israelite tribute bearers carrying heavy and precious gifts.

Photo © Z.Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com

Bottom left: One of ten reliefs on the bronze doors that constitute the eastern portal (the so-called “Gates of Paradise”) of the Baptistery of St. John of Florence, created 1424–1452 by Lorenzo Ghiberti (c. 1378–1455). Detail from the picture “Adam and Eve”; in the center is the creation of Eve: “And the rib that the Lord God had taken from the man he made into a woman and brought her to the man.” (Gen 2:22)

Photograph by George Reader

Bottom right: Detail of the Menorah in front of the Knesset in Jerusalem, created by Benno Elkan (1877–1960): Ezra reads the Law of Moses to the assembled nation (Neh 8). The bronze Menorah was created in London in 1956 and in the same year was given by the British as a gift to the State of Israel. A total of 29 reliefs portray scenes from the Hebrew bible and the history of the Jewish people.

Walter Dietrich

Nahum Habakkuk Zephaniah

Verlag W. Kohlhammer GmbH

Translated from German by Peter Altmann.

1. Edition 2016

All rights reserved

© W. Kohlhammer GmbH Stuttgart

Production:

W. Kohlhammer GmbH, Stuttgart

Print:

ISBN: 978-3-17-020657-1

E-Book-Formats:

pdf: ISBN 978-3-17-029036-5

epub: ISBN 978-3-17-029037-2

mobi: ISBN 978-3-17-029038-9

W. Kohlhammer bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality or content of any external website that is linked or cited, or for that of subsequent links.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

CoverContentEditors’ Foreword Author’s PrefaceIntroductionThe Place of Nahum – Habakkuk – Zephaniah within the Book of the TwelveSynchronic Reading – or: The Northern Empire in Nahum – Habakkuk – ZephaniahDiachronic Analysis – or: The Empires of Assyria and Babylon in Nahum, Habbakuk, and Zephaniah NahumIntroductionSynchronic PerspectiveDiachronic PerspectiveStage I Stage II Stage IIIInterpretationThe Superscription (Nah 1:1)Notes on the Text and TranslationSynchronic AnalysisDiachronic AnalysisSynthesisThe Vengeful God and the Counsel of Belial (Nah 1:2–2:1 [ET: 1:15])Notes on the Text and TranslationSynchronic AnalysisDiachronic Analysis1. Introduction 1:2–92. The Composition in 1:10–2:1 [ET: 1:10–15]SynthesisDown with Nineveh, Away with the Lions! (Nah 2:2–14 [ET:2:1–13])Notes on the Text and TranslationSynchronic AnalysisDiachronic AnalysisSynthesisWoe to the City of Blood, Away with the Locusts! (Nah 3:1–19)Notes on the Text and TranslationSynchronic AnalysisDiachronic AnalysisSynthesisHabakkukIntroductionSynchronic Observations1. The Form and Content of the Book of Habakkuk as a Whole2. The Attempt to Place the Book of Habakkuk as a Whole in its Historical Context Diachronic Analysis1. Composition-critical Breakdown of the Book of Habakkuk 2. The After-Effects of the Book of HabakkukInterpretationThe Superscription (Hab 1:1)Notes on the Text and TranslationSynchronic AnalysisDiachronic AnalysisThe Prophet’s Dispute with God (Hab 1:2–2:4)Notes on the Text and TranslationSynchronic AnalysisDiachronic AnalysisSynthesisA Series of Woe Oracles (Hab 2:5–20)Notes on the Text and TranslationSynchronic AnalysisDiachronic AnalysisSynthesisA Prayer (Hab 3:1–19)Notes on the Text and TranslationSynchronic Analysis Outer Frame A Inner Frame A Core Section A Core Section B Core Section B Inner Frame B Outer Frame BDiachronic AnalysisSynthesisZephaniahIntroductionSynchronic ViewDiachronic View1. The Preexilic Original Layer2. A Late Preexilic Collection3. The Deuteronomistic Redaction4. Postexilic AccretionsInterpretationThe Superscription (Zeph 1:1)Notes on the Text and TranslationSynchronic AnalysisDiachronic AnalysisSynthesisThe Day of Yhwh (Zeph 1:2–2:3)Notes on the Text and TranslationSynchronic AnalysisDiachronic AnalysisSynthesisThe People of God and the Nations (Zeph 2:4–3:8)Notes on the Text and TranslationSynchronic AnalysisDiachronic AnalysisSynthesisThe Time of Salvation (Zeph 3:9–20)Notes on the Text and TranslationSynchronic AnalysisDiachronic AnalysisSynthesisIndexAbbreviationsBibliographyIndexPlan of volumesEditors’ Foreword

The International Exegetical Commentary on the Old Testament (IECOT) offers a multi-perspectival interpretation of the books of the Old Testament to a broad, international audience of scholars, laypeople and pastors. Biblical commentaries too often reflect the fragmented character of contemporary biblical scholarship, where different geographical or methodological sub-groups of scholars pursue specific methodologies and/or theories with little engagement of alternative approaches. This series, published in English and German editions, brings together editors and authors from North America, Europe, and Israel with multiple exegetical perspectives.

From the outset the goal has been to publish a series that was “international, ecumenical and contemporary.” The international character is reflected in the composition of an editorial board with members from six countries and commentators representing a yet broader diversity of scholarly contexts.

The ecumenical dimension is reflected in at least two ways. First, both the editorial board and the list of authors includes scholars with a variety of religious perspectives, both Christian and Jewish. Second, the commentary series not only includes volumes on books in the Jewish Tanach/Protestant Old Testament, but also other books recognized as canonical parts of the Old Testament by diverse Christian confessions (thus including the Deuterocanonical Old Testament books).

When it comes to “contemporary,” one central distinguishing feature of this series is its attempt to bring together two broad families of perspectives in analysis of biblical books, perspectives often described as “synchronic” and “diachronic” and all too often understood as incompatible with each other. Historically, diachronic studies arose in Europe, while some of the better known early synchronic studies originated in North America and Israel. Nevertheless, historical studies have continued to be pursued around the world, and focused synchronic work has been done in an ever greater variety of settings. Building on these developments, we aim in this series to bring synchronic and diachronic methods into closer alignment, allowing these approaches to work in a complementary and mutually-informative rather than antagonistic manner.

Since these terms are used in varying ways within biblical studies, it makes sense to specify how they are understood in this series. Within IECOT we understand “synchronic” to embrace a variety of types of study of a biblical text in one given stage of its development, particularly its final stage(s) of development in existing manuscripts. “Synchronic” studies embrace non-historical narratological, reader-response and other approaches along with historically-informed exegesis of a particular stage of a biblical text. In contrast, we understand “diachronic” to embrace the full variety of modes of study of a biblical text over time.

This diachronic analysis may include use of manuscript evidence (where available) to identify documented pre-stages of a biblical text, judicious use of clues within the biblical text to reconstruct its formation over time, and also an examination of the ways in which a biblical text may be in dialogue with earlier biblical (and non-biblical) motifs, traditions, themes, etc. In other words, diachronic study focuses on what might be termed a “depth dimension” of a given text – how a text (and its parts) has journeyed over time up to its present form, making the text part of a broader history of traditions, motifs and/or prior compositions. Synchronic analysis focuses on a particular moment (or moments) of that journey, with a particular focus on the final, canonized form (or forms) of the text. Together they represent, in our view, complementary ways of building a textual interpretation.

Of course, each biblical book is different, and each author or team of authors has different ideas of how to incorporate these perspectives into the commentary. The authors will present their ideas in the introduction to each volume. In addition, each author or team of authors will highlight specific contemporary methodological and hermeneutical perspectives – e.g. gender-critical, liberation-theological, reception-historical, social-historical – appropriate to their own strengths and to the biblical book being interpreted. The result, we hope and expect, will be a series of volumes that display a range of ways that various methodologies and discourses can be integrated into the interpretation of the diverse books of the Old Testament.

Fall 2012 The Editors

Author’s Preface

I wish to express my thanks to those who supported me in the composition of this commentary:

Professor Helmut Utzschneider (Neuendettelsau) as member of the editorial board responsible for supervising and checking the exegesis.

Monika Amsler, Dr. Sara Kipfer, and Heidi Stucki (all in Bern) for copyediting the German manuscript.

Florian Specker (with the press in Stuttgart) provided an impressive visual presentation of the volume.

Peter Altmann provided a thoughtful translation, Linda Maloney contributed improvements.

Summer 2015 Walter Dietrich

Introduction

The three books of Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah, each only three chapters in length, together yield a surprisingly multifaceted view of biblical prophecy. It includes martial and threatening but also caring and gentle depictions of God; severe indictments of guilt against the people of Yhwh but also comforting promises; rage against foreign nations but also engaging tones toward them; rock hard but also plaintive, lamenting expressions by the prophets; dark images of the future but also radiant brightness. Each of the three books has its particular hue but to a certain degree they are attuned to each other. Within the still broader prophetic mosaic of the Book of the Twelve, these three together and alone contribute definitive colors and contours.

The Place of Nahum – Habakkuk – Zephaniah within the Book of the Twelve1

The Book of the Twelve is in principle ordered chronologically, that is, in three blocks – one of six books and two of three. The following list provides an overview of the introductory headings of each, especially the naming of certain kings.

Hos 1:1: The word of Yhwh that came to Hosea ben Beeri in the days of Kings Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah of Judah, and in the days of Jeroboam ben Joash, the King of Israel.

Joel 1:1: The word of Yhwh that came to Joel ben Pethuel.

Amos 1:1: The words of Amos, one of the shepherds of Tekoa, that he saw concerning Israel in the days of Uzziah, King of Judah, and in the days of Jeroboam ben Joash, the King of Israel, two years before the earthquake.

Obad 1: The vision of Obadiah.

Jonah 1:1: And the word of Yhwh came to Jonah ben Amittai …

Mic 1:1: The word of Yhwh that came to Micah the Moresheth in the days of Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, the Kings of Judah, which he saw concerning Samaria and Jerusalem.

Nah 1:1: An oracle concerning Nineveh, book of the vision of Nahum of Elkosh.

Hab 1:1: The oracle that the prophet Habakkuk the prophet saw.

Zeph 1:1: The word of Yhwh that came to Zephaniah ben Cushi ben Gedaliah ben Amariah ben Hezekiah in the days of Josiah ben Amon, King of Judah.

Hag 1:1: In the second year of King Darius in the sixth month on the first day the word of Yhwh came through the prophet Haggai to Zerubabbel ben Shealtiel, governor of Judah, and to Joshua ben Jehozadak, the high priest.

Zech 1:1: In the eighth month of the second year of Darius the word of Yhwh came to the prophet Zechariah ben Berechiah ben Iddo.

Mal 1:1: An oracle. The word of Yhwh to Israel through Malachi.

The reigns of the named kings are: Jeroboam II of Israel 786–746; then the Judeans Uzziah (= Azariah) 786–736, Ahaz 742–725, Hezekiah 725–696, and Josiah 639–609; finally Darius I of Persia 521–485. The first six books evidently intend to provide illumination during the time when both Israelite states still existed in relative independence alongside each other (8th c.), books 7–9 the time of Assyrian and Babylonian influence on Judah, which now remained alone (7th c.), and books 10–12 the time of the emergence of the province of Yehud under Persian rule (late 6th c.).

Of interest here is especially the second block, books 7–9. Their assignment to the seventh century is understandable. The northern kingdom of Israel no longer plays a role in Nahum – Habakkuk – Zephaniah; Judah stands alone, and opposite it are the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires. The first is present in Nahum and Zephaniah, occasionally under the name “Assur” (Nah 3:18; Zeph 2:13), but more commonly represented by its capital city Nineveh (Nah 2–3; Zeph 2:13–15).2 In contrast, the “Chaldeans” enter the scene in Habakkuk (Hab 1:6) and also stand for the Neo-Babylonian empire in the book of Jeremiah.

While the assignment of these three books to the Assyrian-Babylonian epoch makes good sense, the order is perplexing: why is Habakkuk, in which Babylon is the adversary, not placed after Nahum and Zephaniah, which concern Assur, but instead between them? Answers to this question can be sought by means of both synchronic and diachronic analysis.

Synchronic Reading – or: The Northern Empire in Nahum – Habakkuk – Zephaniah

Scholarship has reached a consensus that the Book of the Twelve Prophets first came into existence in the later Persian, or presumably even in the Hellenistic Period. This means a separation of about half a millennium from the Assyrian and Babylonian eras of the history of Judah that Nahum – Habakkuk – Zephaniah treat! It is quite conceivable that by this point the contours of the two Mesopotamian empires of Assyria and Babylon had converged. The end point of this development can be seen in the book of Daniel, which emerged in the second century. In the two visions of Daniel 2 and Daniel 7 four world empires are brought before the eyes of the viewer. The first of them (relatively speaking still the most noble!) is at one point expressly equated with Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon (Dan 2:38), the following then with the Median, Persian, and Hellenistic empires. Assyria has disappeared from view, or rather from memory – although the first animal of the second vision is a winged lion (Dan 7:4), well known from Assyrian (and admittedly also from Babylonian) iconography. It was still different in Herodotus (ca. 470 b.c.e.), with which the visions of the world empires in Daniel share a considerable amount of content. In his work the first world empire is the (Neo-) Assyrian, the second the Median (not the Babylonian!), the third the Persian.3

An initial explanation for the conspicuous order of Nahum – Habakkuk – Zephaniah could lie in the disappearance of the historical progression of Assyria-Babylon (-Persia) in the collective Jewish memory. “Nineveh” and “the Chaldeans” then both stood for an earlier Mesopotamian empire that once cast its shadow over the history of Judah. From this perspective the order Nahum/Assyria – Habakkuk/Babylon – Zephaniah/Assyria might be reckoned artistic, building a kind of inclusio: a favorite artistic form, especially for material of the prophetic tradition.4

It is not that the northern empires in Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah always play the same role. From this perspective it is much more the case that a chiasm appears. In Nahum 2–3 the prophet vehemently attacks the Assyrian metropolis as greedy beyond measure and immoral without restraint. He paints a scene of how the arrogant without conscience will soon be humbled and plundered. In Hab 1:5–10 the prophet receives an oracle that the Chaldeans will advance with irresistible military power and God’s consent. In Zeph 2:13–15, on the other hand, the prophet threatens Assyria and its capital city, which boastfully declares: “I and none other!” If we view this sequence synchronically with the assumption that later periods generally only remembered one Mesopotamian empire, we can see them drawing the historical background in these texts. In order to appreciate this fully, one must also take into consideration the preceding book of Jonah (in both versions of the canon). Already in this book, which is fictively set back as far as the reign of Jeroboam II, that is, before Assyria’s advance into the southern Levant,5 the metropolis Nineveh appears as full of “wickedness” (Jonah 1:2). Of course, God succeeds, with Jonah’s begrudging help, in bringing them to repentance, in response to which God spares them. The repentance, however, is not enduring; why else would Assyria have struck out against Israel and Judah some time later, thereby provoking Nahum’s cry against the “harlot” Nineveh?

The anti-Nineveh texts in Nahum 2–3 are admittedly not declared to be the words of God; in fact, here the prophet “alone” speaks with tangible disgust. But then, in Habakkuk 1, God himself speaks – and he does not announce something like the immediate destruction of the horrible enemy, but rather their unstoppable advance! However, at the end of the oracle the prophet is told that their coming will only be temporary; they will be shipwrecked on their own self-idolization (their god is their own might, 1:11). Zephaniah 2 ties in with this: Assyria and Nineveh are the dramatic climax of a chain of Divine words directed against enemies in the west, east, south, and north. This intends to say that God will also put a stop to the actions of the greatest and most dangerous of enemy powers.

Read in succession and synchronically, these declarations in Nahum – Habakkuk – Zephaniah concerning the northern empires yield the following statement: Judah had every reason to fear them greatly and hoped understandably that God would eliminate them in good time (Nah). However, God decided to give them free rein (Hab). In the end, however, they would indeed encounter divine judgment (Zeph). This presents a thinly veiled theodicy with regard to the apparent inactivity of God at the demise of the Israelite states. These took place, according to these texts, not because the empires were too powerful or Yhwh powerless. They instead are part of his plan for history, which allows the terrifying enemy a certain amount of time. God’s people must first be chastened, but then their tormentor will be destroyed.6

The creator of the Book of the Twelve probably considered this progression enlightening not only with regard to the past, that is, the Assyrian-Babylonian era, but also for the subsequent period. In the same way that the Mesopotamian empire once carried out a painful, but also temporally limited mandate against Israel, after its completion God rescinded its power so Israel could also count on the temporal limit of every further foreign hegemony, be it Persian or then Greek. The visions in Daniel 2 and 7 conceptualize, or visualize this point of view. No world empire is eternal; even the time of the world itself will end.

The sequence of the books of Nahum – Habakkuk – Zephaniah may be interpreted synchronically somewhat as stated. There are, of course, reasons to assume that the composers of the Book of the Twelve Prophets were not completely free to arrange the books as they wished. So the considerations above were not the cause behind the sequential order of Nahum – Habakkuk – Zephaniah; these instead appeared meaningful after the fact.

Diachronic Analysis – or: The Empires of Assyria and Babylon in Nahum, Habbakuk, and Zephaniah

In scholarship there is overall unanimity that the redactional processes leading to the Book of the Twelve Prophets began long before the Persian or even the Hellenistic period. Proposals that see the emergence of a Book of the Two Prophets Hosea – Amos in the seventh century, in the sixth century becoming a Book of the Four Prophets Hosea – Amos – Micah – Zephaniah,7 and in the fifth century enlarged with the two-prophet-book of Haggai – Proto-Zechariah have a wide appeal.

If this is accurate, then Zephaniah was incorporated relatively early into the prior book of prophets.8 It is unclear, however, when Nahum and Habakkuk were added and why these two books were placed before Zephaniah. In answering this question, the compositional history of Nahum and Habakkuk must be taken into consideration.

The prophet Nahum in my view comes across as fitting in the middle of the seventh century,9 while the Assyrian Empire was still completely intact but had been shaken by the murderous civil war between the Emperor Assurbanipal and his brother Šamaš-šum-ukīn, residing in Babylon. Contrary to Nahum’s great hopes, Nineveh did not perish at that time – not yet. Judah was and remained firmly in the hands of the Assyrian lackey Manasseh (696–641 b.c.e.). Nahum’s attacks were directed against both: the metropolis of the empire (Nah 2:4–3:19) and the ruling class in Judah that was completely oriented toward Assyria (still recognizable under the present text of Nah 1:9–2:3). Whether he originally delivered his oracles orally or immediately wrote them down need not be decided at this point; at least the poetically demanding Nineveh poem points in the direction of the latter conclusion.

The political situation in Judah changed soon after Manasseh’s (late) death. His son and successor Amon fell victim to a palace revolt after only about a year’s reign, after which the ‘am-ha-’arets – known at the latest since the removal of Queen Athaliah, that is, since the middle of the ninth century, as an active political group – killed the murderers of the king and raised the eight-year-old Josiah to the throne (2 Kgs 21:23–24). During his reign (639–609) the Assyrian Empire met its end, allowing Judah to emerge from its shadow. A signal of this was probably that in the year 625 Babylon under Nabopolassar freed itself from Assyrian hegemony. Only three years later – whether by chance or not – Josiah carried out his reform in accordance with the principles of Deuteronomy and, among other things, appears to have brought about the abolition of the Assyrian astral cult in Jerusalem.10 In 612 Nineveh was destroyed and Nahum’s expectations came true in triumphal if gruesome fashion.

Habakkuk probably debuted as the Assyrian era came to an end, but before the Babylonian era had really begun. His attention was turned primarily to the internal circumstances within Judah. “Oppression and violence” spread, “instruction” and “justice” became powerless. The “just” were helplessly handed over to the “wicked” (Hab 1:2–4). Unlike the prophets of the eighth century, Habakkuk did not directly address those responsible (perhaps this would have been too dangerous during his time), but he complained to God. And God answered him: the Chaldeans would rise up and overrun the world (1:5–8) – which arguably intends to say that soon the regime in Jerusalem would be swept aside.

This announcement was apparently fulfilled less quickly than the prophet had hoped.11 So he again turned to God and asked him accusingly (Hab 1:12): “Have you not been Yhwh, my holy God forever?” in order to continue: “Your eyes are too pure to look at evil, and the viewing of anguish you cannot bear. Why do you watch the treacherous, silent when a villain swallows one more righteous than himself?” (Hab 1:12–13). Again the prophet receives an answer. He should write down the “vision” – what is meant is arguably the declaration of the Babylonian advance (1:5–8) – because it will remain in effect “for a set time” (2:2–3). Yhwh himself vouches for the fact that the Chaldeans truly will come.

And how they came! With unimaginable speed they tore the Assyrian Empire off its hinges. In Judah hopes of a better time arose. Deuteronomy, if it was the guideline for the Josianic Reform, contained not only cultic ordinances but also a social law treatise that accommodated the critique of the prophets to a considerable degree. But before this reform could really take effect, the Assyrian giant dragged Judah into a political abyss. When Josiah confronted Pharaoh Necho near Megiddo when Necho was hurrying to help the Assyrians, “he killed him when he saw him.” It sounds strangely casual, as if Josiah did not have any soldiers with him – or as if they did not fight for him. Necho was unable to rescue Assyria, just as he was unable to hinder Babylon from becoming its successor. So Judah, after a short Egyptian interlude, fell under Babylonian hegemony, with the well-known catastrophic ending.

What happened to the traditions of Nahum and Habakkuk during the time of the Babylonian Exile? With Nahum it is likely that wherever “Nineveh” appears, “Babylon” was (also) heard. However, the attacks against the Judahite ruling elite, after these has been severely punished in the meantime, were changed into a comforting message of the liberation of Judah (naturally from the Babylonian yoke) reminiscent of Deutero-Isaiah: “Look, on the mountains are the feet of the herald of joy, the one announcing peace. Celebrate, Judah, your festival, fulfill your vows …. Yhwh is restoring the majesty of Jacob” (Nah 2:1a, 3a).

The Habakkuk tradition underwent an analogous transformation during or shortly after the time of the Exile. The pro-Babylonian elements contained in the text were inverted into anti-Babylonian statements. It is no longer the case that the Chaldeans advance to put an end to the activities of the exploiters in Judah. Instead, “he” – probably the King of Babylon – is now an exploiter himself. “He gathers prisoners like sand,” “he laughs at every stronghold,” “power is his God” (Hab 1:9–10). Habakkuk’s social critique is to that degree changed, so that it is no longer directed toward the nation’s own powerful, but toward the foreign power. Where Habakkuk had threatened an unscrupulous (certainly Judahite) creditor (2:6–7), he now becomes one who “plunders many peoples” and therefore soon “the rest of the nations [will] plunder” – naturally Babylon (2:8). Where Habakkuk had hurled a “woe!” against one who “built a city on blood” (2:12), it becomes a complaint that somebody lets “the nations weary themselves for nothing” – naturally Babylon (2:13). The originally socially critical direction of the series of woe oracles in 2:6–17 now ends in a polemic against divine images, reminiscent of Deutero-Isaiah, and probably also aimed at the Babylonian divine world (2:18–19).

This polemic against idols was picked up by the (early post)exilic book of Habakkuk. It would be more correct to call it the book of Nahum-Habakkuk. Rainer Kessler proposed and supported with solid arguments the thesis that Nahum and Habakkuk were – like Hosea and Amos or Haggai and Proto-Zechariah – already connected before they became part of the Book of the Twelve at a considerably later date.12 This linking probably took place in connection with the above-described revision of both books. That revision also added the headings that are quite similar to one another but single themselves out from the Book of the Twelve: “An oracle concerning Nineveh, book of the vision of Nahum of Elkosh” (Nah 1:1), and “The oracle that the prophet Habakkuk the prophet saw” (Hab 1:1). The noun משׂא and the root חזה are only connected in this way in these two texts.13 The names of the two speakers, on the other hand, including the identification of the origin of the first (“from Elkosh”) and the title of the second (“the prophet”) were probably already extant before the redaction. That is, they belonged to the older traditional material.

The order of the two is very logical: Nahum has the Assyrians as opponent, Habakkuk has the Babylonians. By their connection they now signify the following: Just as Nahum proclaimed the end of Nineveh and that end really took place, the end of Babylon also occurred. The double book of Nahum – Habakkuk is then to be seen as an attempt at self-affirmation by a Judah resurrected from beneath the rubble of the Babylonian era.

Naturally there are textual layers and redactional activity present in all three books – Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah – that are concerned neither with the Assyrian nor with the Babylonian periods of the history of Israel. These layers appear to have left those eras far behind them. It is not that the Persians or even the Greeks expressly enter the scheme. No, the question concerning the identity of Israel or, as the case may be, Judah was no longer determined by its relationship with empires, but alone by its engagement with Yhwh. Israel-Judah is no longer a people whose sovereignty has been stolen by foreign states; it is not even a self-determining nation state; it is nothing but the community of Yhwh. And Yhwh is no longer the one who protects Israel-Judah from empires or snatches them from them. He is the master of the whole world, and as such he holds his hand over his people.

This trans-political status, so to speak, as it appears in Nah 1:2–8; Hab 3:1–19; Zeph 3:9–20, is found on the margin of the three prophetic writings treated here. This makes sense in terms of the literary expansions of a larger sort that are often found only on the margin of an older text corpus and no longer have a place within it.14 These three texts are not homogenous, but they do resemble one another. They are all hymnic in style and sing of the powerful appearance and activity of Yhwh against Evil and the evil ones in the world for the benefit of those belonging to him. In this way a certain consonance emerges between the quite variant traditions of the prophets Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah.

The introduction of Nahum with a psalm and closing of Habakkuk with one so that the two together are framed by psalms left the above postulated Book of Two Prophets of Nahum-Habakkuk15 open to being connected to Zephaniah as well as to further writings of the growing Book of the (Multiple) Prophets. The hymnic elements of these three writings should probably be seen in connection with similar – likewise late – texts in Amos (where they are split into a number of so-called “doxologies” : Amos 4:13; 5:8; 9:5–6) and Jonah (the song of the prophet from the belly of the fish in Jon 2:2–10).

The various psalm texts interspersed through the Persian-period prophetic anthologies suggest the use of the text corpus in a cultic setting. In connection with this we should point out an inconspicuous yet important matter. The Habakkuk psalm (Hab 3:1–19) was not directly connected to the exilic-period polemic against divine images in Hab 2:18–19, but the connection was facilitated by a transitional element that juxtaposed the impotence of other gods with Yhwh’s mighty power: “Yhwh is in his holy temple.16 The whole earth – be silent before him!” (2:19). The cultic call “Be silent before him!” (חס מפני יהוה) rings out similarly three more times in the Book of the Twelve – in Amos 6:10; Zeph 1:7; and Zech 2:17. The earliest appearance was probably in Zeph 1:7. The Persian-period revision inserted the other three: at the end of the Nahum-Habakkuk writing that preceded Zephaniah, quite near the beginning of the Haggai-Proto-Zechariah writing following Zephaniah, and near the beginning of the entire corpus, in the text of Amos. In this manner an arc supported by four posts emerged that spanned almost the entire future Twelve Prophets.17

Nogalski (Literary Precursors) has noted a further literary, or, redactional, form of connection among the writings of the Twelve Prophets. There is an undoubtedly conscious net of catchword links that extends beyond individual components; this is true also of the block of Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah. Micah 7, and Nahum 1 are linked in this way through an entire series of catchwords: enemy, darkness, day, mountain, land, inhabitant, Carmel, Bashan, dust, earth, sea, rage, to pass. Nahum 3 and Habakkuk 1 exhibit a shared martial language (horse, rider, kill, nations, stronghold, power, captivity, destroyer, overpower, flee, king, people, slaughter). Habakkuk 3 and Zephaniah 1 both speak of earth, hill, land, lake, thunder, calamity, and day of terror. Zephaniah 3 and Haggai 1 are connected by the repeated use of the formula “on that day” as well as the term “people/peoples.”

As a result, other books were seemingly added to the older Book of the Four Prophets of Hosea – Amos – Micah – Zephaniah simultaneously with Nahum – Habakkuk. These were Jonah and Haggai – Proto-Zechariah, and possibly also Obadiah and Joel.18 It is easy to recognize the reason for placing Nahum, Habakkuk, and Zephaniah next to each other within this larger arrangement. These three writings treat the Assyrian-Babylonian period. It would have made sense in terms of chronology to separate the double writing of Nahum-Habakkuk and place Zephaniah between them, but this appears to have been nearly impossible. Nor was it necessary because the current order, as shown at the outset, makes very good sense.

Tausende von E-Books und Hörbücher

Ihre Zahl wächst ständig und Sie haben eine Fixpreisgarantie.

Sie haben über uns geschrieben: