11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

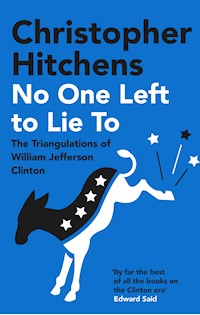

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In this vitriolic polemic, Christopher Hitchens takes on the myth surrounding the most divisive political figures in American political history: Bill Clinton and Hilary Clinton. By far the best of all the books on the Clinton era. - Edward Said In No One Left to Lie To, Christopher Hitchens portrays President Bill Clinton as one of the most ideologically skewed and morally negligent politicians of recent times. In a blistering polemic which shows that Clinton was at once philanderer and philistine, crooked and corrupt, Hitchens challenges perceptions - of liberals and conservatives alike - of this highly divisive figure. With blistering wit and meticulous documentation, Hitchens masterfully deconstructs Clinton's abject propensity for pandering to the Left while delivering to the Right and argues that the president's personal transgressions were inseparable from his political corruption.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS (1949–2011) was a contributing editor to Vanity Fair and a columnist for Slate. He was the author of numerous books, including works on Thomas Jefferson, George Orwell, Mother Teresa, Henry Kissinger and Bill and Hillary Clinton, as well as his international bestseller and National Book Award nominee, God Is Not Great. His memoir, Hitch-22, was nominated for the Orwell Prize and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

ALSO BY CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS

BOOKS

Hostage to History: Cyprus from the Ottomans to Kissinger

Blood, Class, and Nostalgia: Anglo-American Ironies

Imperial Spoils: The Curious Case of the Elgin Marbles

Why Orwell Matters

No One Left to Lie To: The Triangulations of William Jefferson Clinton

Letters to a Young Contrarian

The Trial of Henry Kissinger

Thomas Jefferson: Author of America

Thomas Paine’s “Rights of Man”: A Biography

god is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything

The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Nonbeliever

Hitch-22: A Memoir

Mortality

PAMPHLETS

Karl Marx and the Paris Commune

The Monarchy: A Critique of Britain’s Favorite Fetish

The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice

A Long Short War: The Postponed Liberation of Iraq

ESSAYS

Prepared for the Worst: Selected Essays and Minority Reports

For the Sake of Argument: Essays and Minority Reports

Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere

Love, Poverty and War: Journeys and Essays

Arguably: Essays

COLLABORATIONS

Callaghan: The Road to Number Ten (with Peter Kellner)

Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question

(with Edward Said)

When the Borders Bleed: The Struggle of the Kurds (photographs by Ed Kashi)

International Territory: The United Nations, 1945–95

(photographs by Adam Bartos)

Vanity Fair’s Hollywood (with Graydon Carter and David Friend)

Left Hooks, Right Crosses: A Decade of Political Writing

(edited with Christopher Caldwell)

Is Christianity Good for the World? (with Douglas Wilson)

Hitchens vs. Blair: The Munk Debate on Religion (edited by Rudyard Griffiths)

First published in 1999 by Verso, an imprint of New Left Books.

Published in hardback and e-book in Great Britain in 2012 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This edition published in paperback in 2021 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Christopher Hitchens, 1999, 2000

Foreword to the Atlantic Books edition copyright © 2012 by Douglas Brinkley

The moral right of Christopher Hitchens to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Douglas Brinkley to be identified as the author of the foreword has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 228 0

E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 843 2

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Laura Antonia and Sophia Mando, my daughters

Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgments

Preface

ONE Triangulation

TWO Chameleon in Black and White

THREE The Policy Coup

FOUR A Question of Character

FIVE Clinton’s War Crimes

SIX Is There a Rapist in the Oval Office?

SEVEN The Shadow of the Con Man

Afterword

Index

Foreword

Let’s be clear right off the bat: Christopher Hitchens was duty-bound to slay Washington, D.C., scoundrels. Somewhere around the time that the Warren Commission said there was no conspiracy to kill Kennedy and the Johnson administration insisted there was light at the end of the Vietnam tunnel, Hitchens made a pact with himself to be a principled avatar of subjective journalism. If a major politician dared to insult the intelligentsia’s sense of enlightened reason, he or she would have to contend with the crocodile-snapping wrath of Hitchens. So when five-term Arkansas governor Bill Clinton became U.S. president in 1993, full of “I didn’t inhale” denials, he was destined to encounter the bite. What Clinton couldn’t have expected was that Hitchens—in this clever and devastating polemic—would gnaw off a big chunk of his ass for the ages. For unlike most Clinton-era diatribes that reeked of partisan sniping of-the-moment, Hitchens managed to write a classic takedown of our forty-second president—on par with Norman Mailer’s The Presidential Papers(pathetic LBJ) and Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72 (poor Nixon)—with the prose durability of history. Or, more simply put, its bottle vintage holds up well.

What No One Left to Lie To shares with the Mailer and Thompson titles is a wicked sense of humor, razorblade indictments, idiopathic anger, high élan, and a wheelbarrow full of indisputable facts. Hitchens proves to be a dangerous foe to Clinton precisely because he avoids the protest modus operandi of the antiwar 1960s. Instead of being unwashed and plastered in DayGlo, he embodies the refined English gentleman, swirling a scotch-and-Perrier (“the perfect delivery system”) in a leather armchair, utilizing the polished grammar of an Oxford don in dissent, passing judgment from history’s throne. In these chapters, the hubristic Hitchens dismantles the Clinton propaganda machine of the 1990s, like a veteran safecracker going click-back click-click-back click until he gets the goods. Detractors of Hitchens over the years have misguidedly tattooed him with the anarchistic “bomb-thrower” label. It’s overwrought. While it’s true that Hitchens unleashes his disdain for Clinton right out of the gate here, deriding him on Page One as a bird-dogging “crooked president,” the beauty of this deft polemic is that our avenging hero proceeds to prove the relative merits of this harsh prosecution.

Hemingway famously wrote that real writers have a built-in bullshit detector—no one has ever accused Hitchens of not reading faces. What goaded him the most was that Clinton, the so-called New Democrat, with the help of his Machiavellian-Svengali consultant Dick Morris, decided the way to hold political power was by making promises to the Left while delivering to the Right. This rotten strategy was called Triangulation. All Clinton gave a damn about, Hitchens maintains, was holding on to power. As a man of the Left, an English-American columnist and critic for The Nation and Vanity Fair, Hitchens wanted to be sympathetic to Clinton. His well-honed sense of ethics, however, made that impossible. He refused to be a Beltway liberal muted by the “moral and political blackmail” of Bill and Hillary Clinton’s “eight years of reptilian rule.”

I distinctly remember defending Clinton to Hitchens one evening at a Ruth’s Chris Steak House dinner around the time of the 9/11 attacks. Having reviewed Martin Walker’s The President We Deserve for The Washington Post, I argued that Clinton would receive kudos from history for his fiscal responsibility, defense of the middle class, and an approach to world peace that favored trade over the use of military force. I even suggested that Vice President Al Gore made a terrible error during his 2000 presidential campaign by not using Clinton more. I mistakenly speculated that the Clinton Library would someday become a major tourist attraction in the South, like Graceland. “Douglas,” he said softly, “nobody wants to see the NAFTA pen under glass. The winning artifact is Monica Lewinsky’s blue dress. And you’ll never see it exhibited in Little Rock.”

To Hitchens, there were no sacred cows in Clintonland. With tomahawk flying, he scalps Clinton for the welfare bill (“more hasty, callous, short-term, and ill-considered than anything the Republicans could have hoped to carry on their own”), the escalated war on drugs, the willy-nilly bombing of a suspected Osama bin Laden chemical plant in Sudan on the day of the president’s testimony in his perjury trial, and the bombing of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq on the eve of the House of Representatives’ vote on his impeachment. The low-road that Clinton operated on, Hitchens argues, set new non-standards, even in the snake-oil world of American politics. With utter contempt, Hitchens recalls how during the heat of the 1992 New Hampshire primary (where Clinton was tanking in the polls because of the Gennifer Flowers flap), the president-to-be rushed back to Arkansas to order the execution of the mentally disabled Rickey Ray Rector. “This moment deserves to be remembered,” Hitchens writes, “because it introduces a Clintonian mannerism of faux ‘concern’ that has since become tediously familiar,” and “because it marks the first of many times that Clinton would deliberately opt for death as a means of distraction from sex.”

No One Left to Lie To was scandalous when first published in 1999. The Democratic Party, still trying to sweep Lewinsky under the carpet, didn’t take kindly to a TV gadabout metaphorically waving the semenflecked Blue Dress around as a grim reminder that the Arkansas hustler was still renting out the Lincoln Bedroom to the highest bidder. Hitchens took to the airwaves, claiming that Clinton wasn’t just a serial liar; he actually “reacted with extreme indignation when confronted with the disclosure of the fact.” To be around Clinton, he told viewers, was to subject oneself to the devil of corrosive expediency. It’s not so much that Clinton surrounded himself with sycophantic yes men—all narcissistic presidents do that. It’s that Clinton insisted, no matter the proposition, that his associates and supporters—indeed, all liberals—march in lockstep with his diabolic ways. To do otherwise was a sign of rank disloyalty to the House of Clinton. It was Nixon redux.

History must be careful not to credit Hitchens with this book’s arch title. As the story goes, Hitchens was in a Miami airport on December 10, 1998, when he saw David Schippers, chief investigative counsel for the House Judiciary Committee, on television. The old-style Chicago law-and-order pol was on a roll. “The president, then, has lied under oath in a civil deposition, lied under oath in a criminal grand jury,” Schippers said. “He lied to the people, he lied to the Cabinet, he lied to his top aides, and now he’s lied under oath to the Congress of the United States. There’s no one left to lie to.”

Bingo. Hitchens thought Schippers was spoton. The more he reflected, the angrier he got. The writing process for No One Left to Lie To took only days; he banged it out in a fury. Using his disgust at Clinton’s shameless gall as fuel, he defended the twenty-two-year-old intern Monica Lewinsky, who had over forty romantic encounters in the Oval Office with the president, from bogus charges that she was a slutty stalker. That Clinton had determined to demolish her on the electric chair of public opinion infuriated Hitchens. So he acted. He came to the rescue of a damsel in distress, protecting the modern-day Hester Prynne. It was Clinton, he said, the philanderer-in-chief, who deserved persecution for lying under oath.

There was something a bit New Age Chivalrous about it all. In 2002, Lewinsky wrote Hitchens, on pink stationery, mailed to him c/o The Nation, a note of gratitude for writing No One Left to Lie To and defending her as a talking head in the HBO film Monica in Black and White. “I’m not sure you’ve seen the HBO documentary I participated in,” Lewinsky wrote Hitchens. “I wanted to thank you for being the only journalist to stand up against the Clinton spin machine (mainly Blumenthal) and reveal the genesis of the stalker story on television. Though I’m not sure people were ready to change their minds in ’99, I hope they heard you in the documentary. Your credibility superseded his denials.”

Clinton is for Hitchens emblematic of an official Washington overrun with lobbyists, Tammanybribers, and bagmen of a thousand stripes. But Hitchens doesn’t merely knock Clinton down like most polemicists. Instead, he drives over him with an 18-wheel Peterbilt, shifts gears to reverse, and then flattens the reputation of the Arkansas “boy wonder” again and again. Anyone who gets misty-eyed when Fleetwood Mac’s “Don’t Stop,” the Clinton theme song, comes on the radio shouldn’t read this exposé.

Hitchens tries a criminal case against Clinton (a.k.a. “Slick Willie”) with gusto. No stone is left unturned. He catalogues all of Bubba’s lies. He shames so-called FOBs (“friends of Bill”) such as Terry McAuliffe and Sidney Blumenthal for embracing the two-faced and conniving Clinton under the assumption that an alternative president would be far worse. Was America really worse for wear because Nixon was forced to resign in 1974 and Gerald Ford became president? Would Vice President Al Gore really have been that bad for America compared with the craven Clinton? The heart of this long-form pamphlet is about adults turning a blind eye to abuse of power for convenience’s sake. What concerned Hitchens more than Clinton the man is the way once-decent public servants abandoned Golden Rule morality to be near the White House center of power. Hitchens rebukes the faux separation, promulgated by Clinton’s apologists during the impeachment proceedings of 1998, of the Arkansan’s private and public behavior. “Clinton’s private vileness,” he writes, “meshed exactly with his brutal and opportunistic public style.”

Anyone who defends Clinton’s bad behavior gets the stern Sherman-esque backhand. It’s liberating to think that the powerful will be held accountable by those few true-blooded journalists like Hitchens who have guts; he was willing to burn a Rolodex-worth of sources to deliver the conviction. What Hitchens, in the end, loathes most are fellow reporters who cover up lies with balderdash. Who is holding the fourth estate’s patsies’ feet to the fire? In our Red-Blue political divide, American journalists often seem to pick sides. Just turn on Fox News and MSNBC any night of the week to get the score. Hitchens is reminding the press that for democracy to flourish, even in a diluted form, its members must be islands unto themselves. There is no more telling line in No One Left to Lie To than Hitchens saying: “The pact which a journalist makes is, finally, with the public. I did not move to Washington in order to keep quiet.”

A cheer not free of lampoon hit Hitchens after the publication of No One Left to Lie To. While Clintonistas denounced him as a drunken gadfly willing to sell his soul for book sales, the one-time darling of The Nation was now also embraced by the neoconservative The Weekly Standard. Trying to pigeonhole him into a single school of thought was an exercise in futility. “My own opinion is enough for me, and I claim the right to have it defended against any consensus, any majority, any where, any place, any time,” Hitchens noted in Vanity Fair. “And anyone who disagrees with this can pick a number, get in line, and kiss my ass.”

Having absorbed a bus-load of Democratic Party grief for bashing Clinton’s power-at-any-cost character, Hitchens felt vindicated when, on January 26, 2008, the former president made a racially divisive comment in the run-up to the South Carolina presidential primary. Out of the blue, Clinton reminded America that “Jesse Jackson won South Carolina twice, in ’84 and ’88”—grossly mischaracterizing Barack Obama’s predicted victory over his wife, Hillary Clinton, as a negro thing. So much for a postracial America: Clinton had marginalized Obama as the black candidate. The incident, Hitchens believed, was part-and-parcel to Clinton’s longtime “southern strategy” that entailed publicly empathizing with African-Americans while nevertheless playing golf at a whites-only country club. In chapter two (“Chameleon in Black and White”) Hitchens documents the heinous ways Clinton employed racially divisive stunts to get white redneck support in the 1992 run for the nomination. Examples are legion. Clinton had the temerity to invite himself to Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition Conference just to deliberately insult Sister Souljah for writing vile rap lyrics: a ploy to attract the Bubba vote who worried the Arkansas governor might be a McGovernite. Clinton even told a Native American poet that he was one-quarter Cherokee just to garner Indian support. “The claim,” Hitchens writes, “never advanced before, would have made him the first Native American president. . . . His opportunist defenders, having helped him with a reversible chameleon-like change in the color of his skin, still found themselves stuck with the content of his character.”

Most of the tin-roof Clinton cheerleaders of the 1990s and beyond will be essentially forgotten in history. How many among us, even a presidential historian like myself, can name a Chester Arthur donor or a Millard Fillmore cabinet official? But everyone knows the wit and wisdom of Dorothy Parker and Ambrose Bierce and H.L. Mencken. Like these esteemed literary predecessors, Hitchens will be anthologized and read for years to come. Three versions of Clinton’s impeachment drama (maybe more to come) will remain essential: Clinton’s own My Life, Kenneth Starr’s Official Report of the Independent Counsel’s Investigation of the President, and Hitchens’s No One Left to Lie To. Hopefully Hitchens’s book will continue to be read in journalism and history classes, not for its nitty-gritty anti-Clinton invective and switchblade putdowns, but to remind politicians that there are still reporters out there who will expose your most sordid shenanigans with a shit-rain of honest ridicule. Hitchens salutes a few of them—Jamin Raskin, Marc Cooper, and Graydon Carter among them—in these pages.

Clinton was impeached by the House but acquitted by the Senate. Although he was barred from practicing law, prison time isn’t in his biography. But he paid a peculiar price for his Lewinsky-era corruption: Hitchens’s eternal scorn, which, since his death from esophageal cancer in 2011, is resounding louder than ever with a thunderously appreciative reading public. In the post–Cold War era, Hitchens was the polemicist who mattered most. He understood better than anyone that today’s news is tomorrow’s history. “He used to say to me at certain moments,” his wife, Carol Blue, recalled, “whether it be in the back of a pickup truck driving into Romania from Hungary on Boxing Day 1989, or driving through the Krajina in Bosnia in 1992, or in February 1999 during the close of the Clinton impeachment hearings: ‘It’s history, Blue.’ ”

Douglas Brinkley

February 2012

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to all those on the Left who saw the menace of Clinton, and who resisted the moral and political blackmail which silenced and shamed the liberal herd. In particular, I should like to thank Perry Anderson, Marc Cooper, Patrick Caddell, Doug Ireland, Bruce Shapiro, Barbara Ehrenreich, Gwendolyn Mink, Sam Husseini (for his especial help on the health-care racket), Robin Blackburn, Roger Morris, Joseph Heller, and Jamin Raskin. Many honorable conservative friends also deserve my thanks, for repudiating Clintonism even when it served their immediate and (I would say) exorbitant political needs. They might prefer not to be thanked by name.

The experience of beginning such an essay in a state of relative composure, and then finishing it amid the collapsing scenery of a show-trial and an unfolding scandal of multinational proportions—only hinted at here—was a vertiginous one. I could not have attempted it or undergone it without Carol Blue, whose instinct for justice and whose contempt for falsity has been my loving insurance for a decade.

Christopher Hitchens

Washington, D.C., March 1999

Preface

This little book has no “hidden agenda.” It is offered in the most cheerful and open polemical spirit, as an attack on a crooked president and a corrupt and reactionary administration. Necessarily, it also engages with the stratagems that have been employed to shield that president and that administration. And it maintains, even insists, that the two most salient elements of Clintonism—the personal crookery on the one hand, and the cowardice and conservatism on the other—are indissolubly related. I have found it frankly astonishing and sometimes alarming, not just since January of 1998 but since January of 1992, to encounter the dust storm of bogus arguments that face anyone prepared to make such a simple case. A brief explanation—by no means to be mistaken for an apologia—may be helpful.

Some years ago, I was approached, as were my editors at Vanity Fair, by a woman claiming to be the mother of a child by Clinton. (I decline to use the word “illegitimate” as a description of a baby, and may as well say at once that this is not my only difference with the supposedly moral majority, or indeed with any other congregation or—the mot juste—“flock.”) The woman seemed superficially convincing; the attached photographs had an almost offputting resemblance to the putative father; the child was—if only by the rightly discredited test of Plessy v. Ferguson— black. The mother had, at the time of his conception, been reduced to selling her body for money. We had a little editorial conference about it. Did Hitchens want to go to Australia, where the woman then was? Well, Hitchens had always wanted to go to Australia. But here are the reasons why I turned down such a tempting increment on my frequent-flyer mileage program.

First of all—and even assuming the truth of the story—the little boy had been conceived when Mr. Clinton was the governor of Arkansas. At that time, the bold governor had not begun his highly popular campaign against defenseless indigent mothers. Nor had he emerged as the upright scourge of the “deadbeat dad” or absent father. The woman—perhaps because she had African genes and worked as a prostitute—had not been rewarded with a state job, even of the lowly kind bestowed on Gennifer Flowers. There seemed, in other words, to be no political irony or contradiction of the sort that sometimes licenses a righteous press in the exposure of iniquity. There was, further, the question of Mrs. and Miss Clinton. If Hillary Clinton, hardened as she doubtless was (I would now say, as she undoubtedly is), was going to find that she had a sudden step-daughter, that might perhaps be one thing. But Chelsea Clinton was then aged about twelve. An unexpected black half-brother (quite close to her own age) might have been just the right surprise for her. On the other hand, it might not. I didn’t feel it was my job to decide this. My friends Graydon Carter and Elise O’Shaughnessy, I’m pleased to say, were in complete agreement. A great story in one way: but also a story we would always have regretted breaking. Even when I did go to Australia for the magazine, sometime later, I took care to leave the woman’s accusing dossier behind.