Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

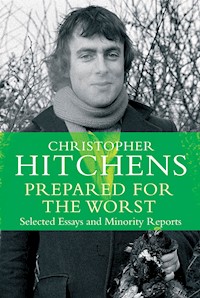

'I suppose that, if this collection has a point, it is the desire of one individual to see the idea of confrontation kept alive' -- Christopher Hitchens Christopher Hitchens is widely recognized as having been one of the liveliest and most influential of contemporary political analysts. Prepared for the Worst is a collection of the best of his essays of the 1980s published on both sides of the Atlantic. These essays confirmed his reputation as a bold commentator combining intellectual tenacity with mordant wit, whether he was writing about the intrigues of Reagan's Washington, a popular novel, the work of Tom Paine, the man George Orwell, or reporting (with sympathy as well as toughness) from Beirut or Bombay, Warsaw or Managua. Hitchens writes clearly, from a well-stocked mind, and is free of the cant that affects many political journalists. - Publishers Weekly

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 763

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PREPARED FOR THE WORST

ALSO BY CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS

Books

Hostage to History: Cyprus from the Ottomans to KissingerBlood, Class, and Empire: The Enduring Anglo-American RelationshipImperial Spoils: The Curious Case of the Elgin MarblesWhy Orwell MattersNo One Left to Lie To: The Triangulations of William Jefferson ClintonLetters to a Young ContrarianThe Trial of Henry KissingerThomas Jefferson: Author of AmericaThomas Paine’s “Rights of Man”: A Biographygod Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons EverythingThe Portable AtheistHitch-22: A MemoirMortality

Pamphlets

Karl Marx and the Paris CommuneThe Monarchy: A Critique of Britain’s Favorite FetishThe Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and PracticeA Long Short War: The Liberation of IraqThe Enemy

Essays

Prepared for the Worst: Essays and Minority ReportsFor the Sake of ArgumentUnacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public SphereLove, Poverty, and War: Journeys and EssaysArguably

Collaborations

James Callaghan: The Road to Number Ten (with Peter Kellner)Blaming the Victims (edited with Edward Said)When the Borders Bleed: The Struggle of the Kurds(photographs by Ed Kash)International Territory: The United Nations(photographs by Adam Bartos)Vanity Fair’s Hollywood (with Graydon Carter and David Friend)

First published in Great Britain in 1988by Chatto & Windus

This edition published in Great Britain in 2014 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Christopher Hitchens, 1988

The moral right of Christopher Hitchens to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 466 2E-Book ISBN: 978 1 78239 499 0

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Ben Sonnenberg

CONTENTS

Introduction

Good and Bad

Blunt Instruments

Datelines

In the Era of Good Feelings

Prepared for the Worst

PREPARED FOR THE WORST

INTRODUCTION

NADINE GORDIMER once wrote, or said, that she tried to write posthumously. She did not mean that she wanted to speak from beyond the grave (a common enough authorial fantasy), but that she aimed to communicate as if she were already dead. Never mind that that ambition is axiomatically impossible of achievement, and never mind that it sounds at once rather modest and rather egotistic, to say nothing of rather gaunt. When I read it I still thought: Gosh. To write as if editors, publishers, colleagues, peers, friends, relatives, factions, reviewers, and consumers need not be consulted; to write as if supply and demand, time and place, were nugatory. What a just attainment that would be, and what a pristine observance of the much-corrupted pact between writer and reader.

The essays, articles, reviews, and columns that comprise Prepared for the Worst do not meet, or approach, the exacting Gordimer standard in any respect. In fact, so far from addressing people posthumously, I feel rather that I’m standing over my collection like an anxious parent. Friends and even acquaintances tend naturally to praise my little son, at least to my face, and I’ve become used to inserting the descant of allowances for myself: you’ve got to realize that he’s a bit spoiled; he’s keener to talk than he is on what he’s saying; he’s a bit lacking in concentration; and so on. Still, the teacher did say just the other day that he was very inquiring and showed distinct promise. Sympathetic, encouraging nods all around.

You don’t get that kind of indulgence for your prose. Hopeless, then, to seek to justify the ensuing. Yes, the piece on Reagan’s mendacity was written to the tune of an emollient week in the national press; yes, the review of Brideshead was composed in response to a TV travesty then in vogue; yes, the report from Beirut understates the horror (didn’t everybody?). But then, might it not be said that the Polish article has a dash of prescience? The Paul Scott essay perhaps a hint of perspective? Forget it. Never explain; never apologize. You can either write posthumously or you can’t.

Fortunately, Ms. Gordimer does set another example that a mortal may try to follow. She combines an irreducible radicalism with a certain streak of humor, skepticism, and detachment. She is also a determined internationalist. My choice among her novels would be A Guest of Honor, wherein the central character sees his beloved revolution besmirched and yet does not feel tempted—entitled might be a better word—to ditch his principles. The whole is narrated with an exceptional clarity of eye, ear, and brain, and there is no sparing of “progressive” illusions. The result is oddly confirming; you end by feeling that the attachment to principle was right the first time and cannot be, as it were, retrospectively abolished by the calamitous cynicism that only idealists have the power to unleash.

Most of the articles and essays in this book were written in a period of calamitous cynicism that was actually inaugurated by calamitous cynics. It was—I’m using the past tense in a hopeful, nonposthumous manner—a time of political and cultural conservatism. There was a ghastly relief and relish in the way in which inhibition—against allegedly confining and liberal prejudices—was cast off. In the United States, this saturnalia took the form of an abysmal chauvinism, financed by MasterCard and celebrating a debased kind of hedonism. In Britain, where there were a few obeisances to the idea of sacrifice and the postponement of gratification, it took the more traditional form of restoring vital “incentives” to those who had for so long lived precariously off the fat of the land. In both instances, the resulting vulgarity and spleen were sufficiently gross to attract worried comment from the keepers of consensus.

Now, I have always wanted to agree with Lady Bracknell that there is no earthly use for the upper and lower classes unless they set each other a good example. But I shouldn’t pretend that the consensus itself was any of my concern. It was absurd and slightly despicable, in the first decade of Thatcher and Reagan, to hear former and actual radicals intone piously against “the politics of confrontation.” I suppose that, if this collection has a point, it is the desire of one individual to see the idea of confrontation kept alive.

Periclean Greeks employed the term idiotis, without any connotation of stupidity or subnormality, to mean simply “a person indifferent to public affairs.” Obviously, there is something wanting in the apolitical personality. But we have also come to suspect the idiocy of politicization—of the professional pol and power broker. The two idiocies make a perfect match, with the apathy of the first permitting the depredations of the second. I have tried to write about politics in an allusive manner that draws upon other interests and to approach literature and criticism without ignoring the political dimension. Even if I have failed in this synthesis, I have found the attempt worth making.

Call no man lucky until he is dead, but there have been moments of rare satisfaction in the often random and fragmented life of the radical freelance scribbler. I have lived to see Ronald Reagan called “a useful idiot for Kremlin propaganda” by his former idolators; to see the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union regarded with fear and suspicion by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (which blacked out an interview with Miloš Forman broadcast live on Moscow TV); to see Mao Zedong relegated like a despot of antiquity. I have also had the extraordinary pleasure of revisiting countries—Greece, Spain, Zimbabwe, and others—that were dictatorships or colonies when first I saw them. Other mini-Reichs have melted like dew, often bringing exiled and imprisoned friends blinking modestly and honorably into the glare. Eppur si muove—it still moves, all right.

Religions and states and classes and tribes and nations do not have to work or argue for their adherents and subjects. They more or less inherit them. Against this unearned patrimony there have always been speakers and writers who embody Einstein’s injunction to “remember your humanity and forget the rest.” It would be immodest to claim membership in this fraternity/sorority, but I hope not to have done anything to outrage it. Despite the idiotic sneer that such principles are “fashionable,” it is always the ideas of secularism, libertarianism, internationalism, and solidarity that stand in need of reaffirmation.

GOOD AND BAD

THOMAS PAINE

The Actuarial Radical

“GOD SAVE great Thomas Paine,” wrote the seditious rhymester Joseph Mather at the time:

His “Rights of Man” explain To every soulHe makes the blind to seeWhat dupes and slaves they beAnd points out liberty From pole to pole.

As befits an anthem to the greatest Englishman and the finest American, this may be rendered to the tune of “God Save the King” or “My Country Tis of Thee.” The effect is intentionally blasphemous and unintentionally amiss. Napoleon Bonaparte, when he called upon Paine in the fall of 1797, proposed that “a statue of gold should be erected to you in every city in the universe.” He fell just as wide of the mark in his praise as Mather had in his parody. Thomas Paine was never a likely subject for a cult of personality. He still has no real memorial in either the country of his birth or the land of his adoption. I used to think this was unfair, but it now seems to me at least apposite.

How right Paine was to call his most famous pamphlet Common Sense. Everything he wrote was plain, obvious, and within the mental compass of the average. In that lay his genius. And, harnessed to his courage (which was exceptional) and his pen (which was at any rate out of the common), this faculty of the ordinary made him outstanding. As with Locke and the “Glorious Revolution” of 1688, Paine advocated a revolution which had, in many important senses, already taken place. All the ripening and incubation had occurred; the enemy was in plain view. But there are always some things that sophisticated people just won’t see. Paine—for once the old analogy has force—did know an unclad monarch when he saw one. He taught Washington and Franklin to dare think of separation.

The symbolic end of that separation was the handover of America by General Cornwallis at Yorktown. As he passed the keys of a continent to the stout burghers, a band played “The World Turned Upside Down.” This old air originated in the Cromwellian revolution. It reminds us that there are times when it is conservative to be a revolutionary, when the world must be turned on its head in order to be stood on its feet. The late eighteenth century was such a time.

“The time hath found us,” Paine urged the colonists. It was a time to contrast kingship to sound government, religion to godliness, and tradition to—common sense. Merely by stating the obvious and sticking to it, Paine had a vast influence on the affairs of America, France, and England. Many critics and reviewers have understated the thoroughness of Paine’s commitment, representing him instead as a kind of Che Guevara of the bourgeois revolution. Madame Roland found him “more fit, as it were, to scatter the kindling sparks than to lay the foundation or prepare the formation of a government. Paine is better at lighting the way for revolution than drafting a constitution … or the day-to-day work of a legislator.” And in her 1951 essay “Where Paine Went Wrong,” Cecilia Kenyon wrote rather coolly:

Had the French Revolution been the beginning of a general European overthrow of monarchy, Paine would almost certainly have advanced from country to country as each one rose against its own particular tyrant. He would have written a world series of Crisis papers and died an international hero, happy and universally honored. His was a compellingly simple faith, an eloquent call to action and to sacrifice. In times of crisis men will listen to a great exhorter, and in that capacity Paine served America well.

This is to forget that Paine went to France as an official American envoy, not as an exporter of revolution. It also overlooks Paine the committee man and researcher, Paine the designer of innovative iron bridges and the secretary of conventions. The bulk of part 2 of The Rights of Man is taken up with a carefully costed plan for a welfare state, the precepts and detail of which would not have disgraced the Webbs, for example:

Having thus ascertained the probable proportion of the number of aged persons, I proceed to the mode of rendering their condition comfortable, which is.

To pay to every such person of the age of fifty years, and until he shall arrive at the age of sixty, the sum of six pounds per ann. out of the surplus taxes; and ten pounds per ann. during life after the age of sixty. The expense of which will be,

Seventy thousand persons at £6 per ann.420,000 Seventy thousand ditto at £10 per ann.700,000£1,120,000This decidedly pedestrian scheme was dedicated to the equestrian Marquis de Lafayette—a man who more closely resembled the beau ideal of Madame Roland’s freelance incendiary.

Paine was even able to rebuke his greatest antagonist for his lack of attention to formality:

Had Mr. Burke possessed talents similar to the author of “On the Wealth of Nations,” he would have comprehended all the parts which enter into and, by assemblage, form a constitution. He would have reasoned from minutiae to magnitude. It is not from his prejudices only, but from the disorderly cast of his genius, that he is unfitted for the subject he writes upon.

This argument from Adam Smith is not the style of a footloose firebrand.

Che Guevara, who was bored to tears at the National Bank of Cuba, once spoke of his need to feel Rocinante’s ribs creaking between his thighs. If Paine ever felt the same, then he stolidly concealed the fact. A large part of his revolutionary contribution consisted of using the skills he gained as an exciseman. “The bourgeoisie will come to rue my carbuncles,” said Marx on quitting the British Museum. The feudal and monarchic predecessors of the bourgeoisie actually did come to regret teaching Paine to count and to read and to reckon, even to the paltry standard required of a coastal officer.

You may see the doggedness (and, sometimes, the accountancy) of Paine in numerous passages—almost as if he were determined to justify Burke’s affected contempt for “the sophist and the calculator.” The prime instances are the wrangle over slavery and the Declaration of Independence, and the negotiation over the Louisiana Purchase. Both involved a correspondence with Thomas Jefferson, which has, unlike much of Paine’s writing, survived the bonfire made of his papers and memoirs.

Jefferson withdrew a crucial paragraph from the Declaration, consequent upon strenuous objection from Georgia and South Carolina. In its bill of indictment of the king, it had read:

He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of INFIDEL powers, is the warfare of the CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought and sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce. And that this assemblage of horrors might want no feet of distinguished dye, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them by murdering the people on whom he has obtruded them, thus paying off former crimes committed against the LIBERTIES of one people with crimes which he urges them to commit against the LIVES of another.

In his earlier pamphlet against slavery, Paine had written:

These inoffensive people are brought into slavery, by stealing them, tempting kings to sell subjects, which they can have no right to do, and hiring one tribe to war against another, in order to catch prisoners … an hight of outrage that seems left by Heathen nations to be practised by pretended Christians… . That barbarous and hellish power which has stirred up the Indians and Negroes to destroy us; the cruelty hath a double guilt—it is dealing brutally by us and treacherously by them.

Either Paine actually wrote the vanquished paragraph or, as William Cobbett said of the Declaration itself, he was morally its author. His biographer Moncure Conway, who fairly tends to find the benefit of any doubt, comments on the excision and summons an almost Homeric scorn to say:

Thus did Paine try to lay at the corner the stone which the builders rejected, and which afterwards ground their descendants to powder.

Conway and Paine both half-believed that revolutionaries make good reformists, a belief obscured by the grandeur of Conway’s phrasing.

Anyway, Paine was not always to be Cassandra. As elected clerk to the Pennsylvania Assembly, he labored hard on the preamble to the act which abolished slavery in that state. He is generally, but not certainly, credited with its authorship. At any rate, his clerkly efforts gave him the satisfaction of seeing the act become law on March 1, 1780, as the first proclamation of emancipation on the continent.*

More than two decades later, on Christmas Day, 1802, Paine wrote to Jefferson with a well-crafted suggestion of another kind.

Spain has ceded Louisiana to France, and France has excluded the Americans from N. Orleans and the navigation of the Mississippi: the people of the Western Territory have complained of it to their Government, and the government is of consequence involved and interested in the affair. The question then is—what is the best step to be taken?

The one is to begin by memorial and remonstrance against an infraction of a right. The other is by accommodation, still keeping the right in view, but not making it a groundwork.

Suppose then the Government begin by making a proposal to France to repurchase the cession, made to her by Spain, of Louisiana, provided it be with the consent of the people of Louisiana or a majority thereof… .

The French treasury is not only empty, but the Government has consumed by anticipation a great part of the next year’s revenue. A monied proposal will, I believe, be attended to; if it should, the claims upon France can be stipulated as part of the payments, and that sum can be paid here to the claimants.

I congratulate you on the birthday of the New Sun, now called Christmas day; and I make you a present of a thought on Louisiana.

This is not exactly visionary (the only revolutionary bit is in the valediction), but it is very good actuarial radicalism. Paine did not foresee the imperial delusions harbored by Bonaparte—it has to be admitted that Burke was more prescient on that point—but five years after the Corsican had offered him a statue of gold, he was still able to take a more solid bargain off him.

Paine was schooled in the rational, down-to-earth style of the English artisan’s debating club. His earliest pamphlet was a technical treatise on the folly of the Crown in underpaying the excisemen. His fellow workers in his second trade, that of corset making, were no less steeped in the fundamentals. He never forgot to consider the material substratum that is necessary for happiness or even for existence.

The Puritan revolutionaries influenced Paine also. In preaching to the men and women of no property, he was always contrasting man as made by God to mankind as reduced by priestcraft and monarchy. The echoes of the Diggers and Levelers, and of Milton’s “good old cause,” are everywhere to be found in his prose. And, though he repudiated the suggestion with some heat, it’s very plain that he must have read the second Treatise on Civil Government by John Locke. Paine was a borrower and synthesizer, not an originator.

Paine’s arguments about natural right and human liberty followed the tiresome fashion of the time in claiming descent from Genesis. Here again, he put himself in debt to Locke and to the long English Puritan tradition of asking, “When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?” He was somewhat wittier and pithier than Locke, but he did continue to take the arguments of the “Church and King” faction at face value in making his case:

For as in Adam all sinned, and as in the first electors all men obeyed; as in the one all mankind were subjected to Satan, and in the other to sovereignty; as our innocence was lost in the first, and our authority in the last; and as both disable us from reassuming some former state and privilege, it unanswerably follows that original sin and hereditary succession are parallels. Dishonorable rank! Inglorious connection!

Staying in Locke’s footsteps, Paine also ridiculed the Normans, whose conquest of Britain was the fount of kingly authority. In fact, this essentially populist ridicule provided the occasion for a wonderful story about Benjamin Franklin, who, while envoy at Paris, received an offer from a man

stating, first, that as the Americans had dismissed or sent away their King, that they would want another. Secondly, that himself was a Norman. Thirdly, that he was of a more ancient family than the Dukes of Normandy, and of a more honourable descent, his line never having been bastardised. Fourthly, that there was already a precedent in England, of kings coming out of Normandy: and on these grounds he rested his offer, enjoining that the Doctor would forward it to America.

Franklin didn’t forward the letter.

Paine was most emphatically a moralist. His stress was always upon condition, not upon class. Still, his best writing and his finer episodes are improvisations upon the moment. His most brilliant are of course the exhortations to Washington’s army and the splendid rebuff to Admiral Lord Richard Howe (“In point of generalship you have been outwitted, and in point of fortitude, outdone”). His least impressive are the entreaties to the French to spare their king from the knife. It is to Paine’s credit that he urged clemency—having once written so dryly of Burke’s concern for the plumage rather than the bird—and that he took a frightful personal risk to do so. One is tempted to find in him the figure of a humane moderate, who wanted to temper the French Revolution just as he had itched to spur the American one. John Diggins actually tries this line in Up from Communism, where he characterizes Paine as “another fellow-traveller whose revolutionary idealism had drowned in the Jacobin terrors of the Eighteenth Century.” But it won’t do. For one thing, if Paine was a fellow traveler with anyone, it was with the Girondins. For another, it was all up with the French king, just as it had been all up with the English one. The French had had more to endure than the American colonists and could not put the Atlantic between themselves and those who wished for revenge or reconquest. Paine, for all his scruple and decency, was out of his depth in trying to brake the pace of events. Mather put it well in another of his poems, “The File-Hewer’s Lamentation”:

An hanging day is wanted;Was it by justice granted,Poor men distressed and dauntedWould then have cause to sing:To see in active motionRich knaves in full proportionFor their unjust extortionAnd vile offences, swing.

Even so, Paine did not sicken of revolution as a result of his rough handling by the Committee of Public Safety. To the end of his days, which were shortened by the experience, he proudly pointed out that “the principles of America opened the Bastille.” He never diluted any of his convictions, regretting, rather, the slackening of respect for the ideals of the Revolution and insisting, for example, that the Louisiana Purchase should be conditional upon emancipation.

PAINE PASSED his last years fending off the jibes of the Federalists and the taunts of the religious. As Carl Van Doren says, he could have survived The Rights of Man if he had not written The Age of Reason. But the pious were (and are) too crass to see how devotional a book The Age of Reason really is. The cry of “filthy little atheist,” directed at Paine at the time and resurrected by Theodore Roosevelt on a later occasion, reflects only ignorance. Paine was no more an atheist than Luther (another conservative revolutionary) or Milton (likewise). He was as biblical and sound as any “plain, russetcoated captain” in Cromwell’s New Model Army. But even at the close, with clerics gathering around his sickbed in hopes of a recantation, Paine roused himself to make such distinction as he could between faith and superstition, Addressing the reverend gentlemen who had squabbled over the corpse of Alexander Hamilton, he wrote to a clergyman named Mason:

Between you and your rival in communion ceremonies, Dr Moore of the Episcopal church, you have, in order to make yourselves appear of some importance, reduced General Hamilton’s character to that of a feeble-minded man, who in going out of the world wanted a passport from a priest. Which of you was first applied to for this purpose is a matter of no consequence. The man, sir, who puts his trust and confidence in God, that leads a just and moral life, and endeavors to do good, does not trouble himself about priests when his hour of departure comes, nor permit priests to trouble themselves about him.

He remained staunch to his last hour, drawing down a hail of petty abuse and innuendo. The godly did not even refrain from insinuating that Paine was in thrall to the brandy bottle, as if it had been this that sustained him through war, revolution, poverty, incarceration, and the calumny and ingratitude of the American Establishment.

His courage was by no means Dutch and was worthy of a better cause than theism. It required bravery as well as common sense to give the ambitious objective “United States of America” to the enterprise of the thirteen colonies (Paine was the first to employ the name). It required something more than prescience to say plainly, in The Rights of Man, that Spanish America would one day be free. And sometimes Paine’s aperçus give an awful thrill:

That there are men in all countries who get their living by war, and by keeping up the quarrels of Nations, is as shocking as it is true; but when those who are concerned in the government of a country, make it their study to sow discord, and cultivate prejudices between Nations, it becomes the more unpardonable.

Paine belongs to that stream of oratory, pamphleteering, and prose that runs through Milton, Bunyan, Burns, and Blake, and which nourished what the common folk liked to call the liberty tree. This stream, as charted by E. P. Thompson and others, often flows underground for long periods. In England, it disappeared for a considerable time. When Paine wrote that to have had a share in two revolutions was to have lived to some purpose, he meant France and America, and not the narrow, impoverished island that he had last fled (on a warning from William Blake) with Pitt’s secret police on his tail.

But when the Chartists raised their banner decades later and put an end at some remove to the regime of Pitt and Wellington, it was Paine’s banned and despised pamphlets that they flourished. Burns’s “For a’ That, and a’ That” has been convincingly shown, in its key verses, to be based upon a passage in The Rights of Man.

Marx does not seem to have heard of him, though there is in The Rights of Man a sentence that pleasingly anticipates the opening of The Eighteenth Brumaire:

Man cannot, properly speaking, make circumstances for his purpose, but he always has it in his power to improve them when they occur; and this was the case in France.

And, not long ago, I came across the following:

Let it not be understood that I have the slightest feeling against Henry of Prussia; it is the prince I have no use for. Personally, he may be a good fellow, and I am inclined to believe that he is, and if he were in any trouble and I had it in my power to help he would find in me a friend. The amputation of his title would relieve him of his royal affliction and elevate him to the dignity of a man.

That was Eugene Debs, giving a hard time to the fawners of New York high society in 1907. To say that Debs could not have written in this manner without the influence of Paine is not to diminish Debs, who acknowledged his debt. Traces of the same lineage can be found in the work of Ralph Ingersoll and (a guess) in the finer scorn of Mark Twain and H. L. Mencken. Can it be coincidence that the founding magazine of the NAACP was called The Crisis? When Earl Browder spoke of communism as “Twentieth-century Americanism,” and when Dos Passos used Paine to counterpose American democracy to communism, they were both straining, to rather less effect, to pay the same compliment.

Yeats used to speak of a “book of the people,” in which popular yearning was inscribed and wherein popular memories of triumph over tyranny and mumbo jumbo were recorded. Tom Paine wrote a luminous page of that book. But, just as he was only a revolutionary by the debased standards of his time, he can only be commemorated as one by contrast to the reactionary temper of our own.

(Grand Street, Autumn 1987)

*In his Reflections of a Neoconservative, Irving Kristol presses anachronism into the service of chauvinism: “Tom Paine, an English radical who never really understood America, is especially worth ignoring.”

THE CHARMER

PERHAPS YOU might suggest a time when I could reach Mr. Farrakhan by telephone …?

“Try on Monday.”

“Certainly, thank you. Oh—isn’t that Columbus Day?”

“Not for us it isn’t.”

Thus the abortion of one of my several approaches to the office of the Final Call in Chicago. I had just been to hear Louis Farrakhan speak at Madison Square Garden on October 7, 1985. Prior to that evening, I had seen only two attention-getting public speeches delivered in the flesh, as it were. One was Edward Kennedy’s unctuous address to the Democrats in Philadelphia in June 1982, the other was Mario Cuomo’s crowd-pleasing convention “keynote” in San Francisco two years later. Both of these featured invocations of Ellis Island, brave immigrants, and the American dream. Both of them exhibited pride of ancestry and pride in the struggle for a place in the New World.

Immigrant chic, as James Baldwin pointed out two decades ago, is a form of uplift and consolation denied to black Americans. How, I wonder, do blacks feel when they see Lee Iacocca grandstanding about the Statue of Liberty? Many of them, I presume, are too polite to say. But the atmosphere at the Garden could hardly have been in bolder contrast. The opening prayer made repeated reference to the congregation’s being “here in the wilderness of North America.” In his warm-up speech, Stokely Carmichael, who has named himself Kwame Touré after the two most grandiose and disappointing pan-Africanist despots, eulogized Africa as the mother of religion and culture, and cited Freud as the authority for Moses’ having been black. As he entered his peroration against Zionism, attention was distracted from his white dashiki by the spirited efforts of the interpreter for the deaf to keep in step.

This officer had much less trouble conveying into gestures the clear, honeyed tones of the main attraction. Louis Farrakhan does not do black talk. He does not do jive. He speaks in a clear, remorseless English, varying only the pitch and the speed. A calypso artist called the Charmer until he saw the light in 1955, he wrote a play about the black travail and called it Orgena, which is “a Negro” spelled backward. The hit song from this play, which filled Carnegie Hall in its time, was “White Man’s Heaven Is a Black Man’s Hell (Heed the Call Y’All).” The key verse is from Genesis (15:13–14), promising redemption and revenge. Like Jesus, with whom he frequently compares himself, Farrakhan has not read the New Testament. He sings well on the recording I possess but enjoys cutting short any laughter with a menacing remark: the charmer has a cruel streak.

By now, everybody knows what Farrakhan said that night, and what Farrakhan thinks, about the Jewish people. In particular, and although most New York newspapers prudently played it downpage or not at all, his warning that “you can’t say ‘Never Again’ to God, because when He puts you in the ovens you’re there forever” has become defining and emblematic. And in a way that it never was in the days of Malcolm X or even Elijah Muhammad.

In May 1962, just after the Los Angeles Police Department had cut a lethal swath through the members of the local Muslim temple, Malcolm X opened a public meeting with what he called “good news.” One hundred and twenty-one “crackers” of the all-white Atlanta Art Association had died in a plane wreck at Orly. There was a tremendous row about this remark, along conventional lines of hate being no answer to hate, but it was clear even then that Malcolm felt that all whites—without discrimination, so to say—were courting judgment. It was to become clearer, though, that he was in transition from racial nationalism to radicalism and was a man who could sicken of his own bile. Farrakhan, a much smoother and shallower person, who wrote in Muhammad Speaks in December 1964 that “such a man as Malcolm is worthy of death,” is, if anything, in transition the other way. Otherwise, to paraphrase an ancient question, Why the Jews?

In her anxious, thoughtful, and unreviewed book The Fate of the Jews (New York: Times Books, 1983), Roberta Strauss Feuerlicht describes a series of meetings on black–Jewish tension which were held at Manhattan’s 92nd Street Y in the early part of 1981. At the first of these, the black spokesman was the educator Dr. Kenneth Clark, whose study of racial discrimination was cited by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education. He wondered aloud at one point why it should be this relationship, rather than, say, black–Catholic relations, that was so emotionally combustible:

Clark’s rhetorical question was unexpectedly answered a few minutes later. A woman told him he underestimated how important survival is to Jews and said, “One of the reasons there isn’t quite as much dialogue with the Catholics is the Catholics aren’t worried that the blacks are going to shove them into the oven.”

Though the woman continued to talk, Clark winced, as though he had been physically struck. “My goodness,” he said very softly. Then he spoke louder, asking incredulously, “Did you say something about blacks shoving people into ovens?”

At a subsequent meeting:

A young black woman, who happens to be married to a Jew though she didn’t say so, said that Jews are always talking about the 1960s, but what have they done for blacks lately? A few minutes later, someone thrust a note into her hand. It said:

Dear Lady,

Is the lives of the children of my friends killed in the civil rights march enough for you? That’s what some Jews have done for you.

There was no signature, and it was a long way from the spirit of Schwerner, Chaney, and Goodman.

Feuerlicht’s book, which is full of anguish and decency, suffers from its implicit belief that anti-Semitism is a prejudice like any other. This belief, though it may be convenient for pluralism and for civilization, is not well founded. Anti-Semites are inhibited from making exceptions or distinctions. All of their worst enemies are Jews. Their weaker brethren—the anti-Catholics and anti-Masons—emulate anti-Semites only in seeing their devils wherever they look. Anti-Semitism is a theory as well as a prejudice. It can be, and is, held by people who have never seen a Jew. It draws upon vast buried resources—calling upon Scripture, blood, soil, gold, secrecy, and predestination. It may have special attractions for those who are themselves victimized by their own kind. And typically the anti-Semite has an interest, however sublimated, in a Final Solution. Nothing else will do. The usual outward sign of this is an inability to stay off the subject.

Thus, while it may be true that some of Farrakhan’s audience is drawn by resentment of the political and moral strength of the American Jews (Jesse Jackson was never more instructive or more honest than when he said that he was tired of hearing about the Holocaust), Farrakhan himself is uninterested in that banal kind of fedupness. For him, the Jews are a question of the Law and the Book. His meeting demonstrated as much by two significant gestures to white anti-Semitism which went unreported. The first of these was made by the introducing speaker, who said that “Minister Farrakhan” was a true champion. He had “even knocked Henry Ford out of the ring.” Why, Henry Ford was made to apologize for his writings on the international Jew. But Minister Farrakhan, he didn’t apologize to anybody, and there was no one around who could make him. This, evidently, was something more than an appeal to black self-respect.

The second such insight came from Farrakhan himself, when he spoke of the power of the Jewish lobby in Washington and of the numbers of congressmen who were honorary members of the Knesset. These people, he said, are “selling America down the tubes.” Here is the precise language employed by the Liberty Lobby, the Klan, and the right-wing patriots who surfaced at the time of the oil embargo. Why is Farrakhan, who doesn’t vote or care for Columbus Day, and who thinks America is Babylon, so solicitous of this interpretation of its interests? Dr. Clark’s question is answered. Yes, somebody did say something about blacks shoving people into ovens. The fact that it was said under the rubric of religious prophecy may console those who respect that kind of thing.

In his book The Ordeal of Civility, John Murray Cuddihy wrote of black–Jewish rivalry:

The cold war at the top, that between the literary-cultural representatives of the contending groups, is a war for status: the status at issue is the culturally prestigeful one of “victim.”

At a slightly less elevated level, black demagogy turns on the Jews not in spite of the fact that they are more liberal and more sensitive to the persecuted, but because of it. Could rationalism, not to speak of socialism, suffer a worse defeat?

There’s no doubt who prevails in Cuddihy’s “prestigeful” stakes, at least as far as white sympathy goes. And Farrakhan’s repeated claim for the numbers martyred by slavery is a self-conscious competition with the six million rather than (as is interestingly the case with some species of anti-Semite) a denial of them.

The tendency of victims not to identify with one another and even to take on the oppressor’s least charming characteristics is strongly marked and has been much recorded. “Asked if he would accept whites as members of his Organization of Afro-American Unity, Malcolm said he would accept John Brown if he were around today—which certainly is setting the standard high.”* Invited to consider Jews as allies, while modeling its own myth on that of Zion in captivity, the Nation of Islam is instead set upon the same quest for racial destiny which has led Israelis to emulate European colonialism. What this says about the future of illusion, and about the cost of religion to humanity, is as much as one can bear to contemplate.

(Grand Street, Winter 1986)

*Eldridge Cleaver, describing Black Muslim prison life in one of the few worthwhile passages of Soul on Ice.

HOLY LAUD HERETIC

IN JANUARY 1986, an International Colloquium of the Jewish Press was held in Jerusalem. Its most tempestuous session concerned the various “responsibilities” of the critic. And in this session, which was entitled “The Press and the Preservation of the Jewish People,” the most forward participant was Norman Podhoretz. In his remarks, the editor of Commentary went somewhat further than he had in “J’Accuse” (Commentary, September 1982) and “The State of World Jewry Address” (1983). He stated plainly that “the role of Jews who write in both the Jewish and the general press is to defend Israel, and not join in the attacks on Israel.” Turning to the Israeli press proper, he admonished its writers and editors “to face the fact that the internal political debate in Israel, when it reaches a certain pitch of intensity, has an extremely damaging effect in the U.S. and other diaspora countries. It is hard for Israeli journalists to understand how crushing a blow they deal the political fortunes of Israel in the U.S. by calling Israel a fascist country—as many of them do; what damage they do to Israel by blowing the Kahane phenomenon out of proportion.” Perhaps in an effort at paradox, Podhoretz declared that “all this helps Israel’s enemies—and they are legion in the U.S.—to say more and more openly that Israel is not a democratic country.” Or, as he put it later and more gnomically in the same session: “The statement ‘freedom to criticize’ is only the beginning of the discussion, not the end of it.”

In one way, this was the adaptation to Israel of the standard neoconservative three-card monte as it is played in America: America is a democracy which allows demonstrations against its policies; the Soviet Union does not allow such demonstrations; the American demonstrations are therefore a form of aid and comfort to the Soviet Union. Sometimes the first or second card of this trick is ineptly played, resulting in the unintentionally absurd injunction “This is a democracy, so shut up!” or the even flatter injunction that the critical voice should relocate in Moscow. Podhoretz, even as he defends the undemocratic Israeli Right to American audiences, will invoke the very “democracy” that, when he is in Israel itself, he attempts to enfeeble. And the often-heard slogan about “the only democracy in the Middle East” has its effect on liberal journals like Dissent and the new Tikkun, which would themselves never pass a Podhoretz loyalty test.

Neither Western nor Israeli “democracy,” of course, is a sham. But the conservative defense of it often rests upon a half-truth. Whether in the weak and propagandistic form of a Jeane Kirkpatrick syllogism (authoritarianism is to be preferred to totalitarianism and, in practice, often to democracy also) or in the more muscular form of Reagan’s “Free World” rhetoric, the conservative position in Israel and in the United States exhibits the same irony. It consists of the relentless iteration of a “democracy” for which, in the real world, the speaker has contempt. This explains the vicarious envy with which people like Podhoretz write about the “unfettered” freedom of communist dictatorships to act without restraint. In this ideological imagination, freedom is a sort of moral credit, which may be banked but should not be drawn upon. Objectors to this logic may be denounced as communists. If they challenge the deep alliance between the American and Israeli establishments, they may well be called fascists, too. And the striking thing about this fundamentally conservative relationship between facts and values is how much support and justification it gets from liberals. Of no other power relationship between Washington and a foreign government can this be said.

THIS SHORT preface introduces an Israeli who, over the past decade and more, has won an increasing reputation. Unlike the nonexistent critics whom Podhoretz denounces but never cites, he does not believe that Israel is a fascist country. But he does believe that it is menaced by fascism, and if taken over by it would constitute a fascistic menace to others. Professor Israel Shahak, Holocaust survivor and pioneer Zionist, devotes himself to the study and dissemination of observable currents in Israeli society as evidenced in the Hebrew press. He believes firmly in the virtues of Israeli pluralism and democracy, and has done more to uphold and defend them than most of those who make of them a mere boast. Although he is best known for his stand on the rights of the remaining Palestinian Arabs, he is also heavily engaged in the battle between fundamentalist and secular Jews which now rages so bitterly and which he was among the first to foresee. What follows is an attempt to make his findings and his principles better known and better understood.

In the course of a week’s discussion with Shahak, I endeavored to keep each daily session self-contained. As far as possible, this profile and analysis follows the pattern of our discussions and disagreements. We began with biography.

Israel Shahak was born on April 28, 1933, into a religious and Zionist family in Warsaw. Although his father, a leather merchant, was from a long line of rabbis and had qualified to be one himself, he had developed at a slight angle to strict orthodoxy. The young Shahak was educated in Polish and Hebrew. The family home was damaged in the siege of Warsaw in 1939, which was soon followed by the Nazi creation of the ghetto, but he recalls no serious hardship until 1942. News of the Final Solution had come in the form of rumor from other towns and was more intensely discussed by the children and youngsters than their protective parents ever suspected. Each community felt that it might be the one to be spared; in Warsaw, the given reasons for optimism were the presence of embassies from the neutral states and the fact that the Jewish population performed much useful labor for the occupiers. Shahak’s father was the Pangloss of the family, and an early memory is of disputes between parents about the advisability of flight. This argument was cut short by the abrupt removal of the Shahaks to Poniatowa concentration camp, but it resumed there. It culminated in Shahak’s mother leaving the camp as the barbed wire went up. Assisted by good Polish friends and taking her son, she left her husband behind. Sheltered for a while by a Polish family, and making use of the trade in false passports from Latin America, mother and son were not “selected” for extermination when apprehended, but they did spend some grueling time in Bergen-Belsen. One week before the liberation, they were transported by rail to Magdeburg and rescued on April 13, 1945, by the American army.

It took only a brief while to establish that the father had perished in a mass extermination by shooting and that Israel’s older brother, who had left Poland well before the war, had been killed while serving in the Royal Air Force in the Far East. This gave the family the right to settle in England, and young Israel, who now by Jewish custom headed the family, was asked to decide on their future home. He opted unhesitatingly for Palestine, and he and his mother disembarked at Haifa on September 8, 1945. The succeeding six years were, he says, ones of “utmost happiness.” He was a good pupil, although occasionally slapped for asking impertinent questions. His mother remarried successfully (having even asked his permission as head of the family), and stepfather and son took to one another at once. Shahak was too young to serve in the 1948 war, but old enough to feel the excitement of delivering messages and running errands. The memory of ghastliness in Central Europe was not erased—he says it comes back vividly when he is ill—but it was overcome.

Shahak knew very well that there were atheist Jews, because his mother abandoned her belief in God as a result of the Holocaust. He also knew that many Jews were anti-Zionist, because he had had a grandmother in prewar Poland who was wont to spit at the mention of Herzl’s name. But he remained both Orthodox and a staunch Ben-Gurionist until the 1950s. His repudiation of both religion and Zionism took place over a long period and, though related, are not identical. For convenience, the two anticonversions can be discussed separately.

It was while he was studying Holy Writ for his final examinations that he found a disturbing symmetry between the biblical atrocities and extirpations enjoined by a jealous God and the genocidal propaganda of the Nazis. He feels that the work of Maimonides and Averroës, with its attempted reconciliation between religion and philosophy, may have been at work on his subconscious. But even these two savants had observed the Commandments, which Shahak now found himself unable to obey. In his lengthy essay “The Jewish Religion and Its Attitude to Non-Jews,” he sets out his generalized objections to the sectarianism, absolutism, and racialism of Orthodox doctrine and argues that an attempt by Jews is under way to undo the emancipation of Jews by the Enlightenment. I shall return to this, but I want to emphasize meanwhile that Shahak would insist on this position even if there were no “Palestinian problem.”

In any case, his misgivings on that score were to come later, with Israel’s attack on Egypt in October 1956. He was shocked, he says, by the lying and deception which went into the collusion with Britain and France against Nasser during the Suez crisis. He was even more shocked by Ben-Gurion’s boast that the war would establish “the kingdom of David and Solomon.” But the Eisenhower-enforced retreat from Suez was so swift, and the subsequent decade so peaceful and prosperous, that it was not until the conquest of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967 that he faced the idea of his adopted country as at once expansionist and messianic. In the intervening years, he had visited the United States as a lecturer in chemistry at Stanford and had had the opportunity to contrast its open atmosphere with the conformist environment at home. He was struck by the rapid advances of the civil rights movement in the Deep South, and the experience taught him, he says, to admire the United States Constitution. He advocates a similar constitution for Israel in his bulletins. (Many who are called “anti-American” by the neoconservatives are in fact admirers of American liberty and would prefer it to the sort of government with which America so often colludes.)

What, now, are his convictions? He is neither a materialist atheist nor a Marxist, preferring to call himself a disciple of Spinoza. “It may not be said of any philosophy or metaphysic that it is true, but it may be said not to be contradictory.” The work of Spinoza, he also finds, is “conducive to intellectual happiness and to fortitude in the face of calamity.” As a self-defined elitist, Shahak reposes little faith in “the masses,” preferring to rely upon “good information that is addressed to educated minorities.” And like Spinoza, he is alone. Not a joiner or a party man, he has voted for the Rakah communist candidates in the last three elections, solely because of their stand on Palestinian self-determination. His apartment on Bartenura Street is almost a caricature of the scholarly dissident’s warren of tottering files and unsorted shelves, a cartoon of the one-man show. His mimeographed digest of salient admissions in the Hebrew press, which he translates and sends out to friends and contacts all over the world, has, typically, no title. By “salient admissions” I mean the inadvertent manner in which the devout choose to reveal themselves. One might as well say the advertent manner in which they do this, given stories like the following: “It is forbidden to sell apartments to non-Jews in Eretz Israel—‘not even one apartment,’ says the Sephardi chief rabbi, Mordechai Eliahu, in response to a question from members of the Shas Party in Jerusalem, who are campaigning against selling and renting apartments to Arabs in the Jerusalem suburb of Neve Ya’akov” (Ha’aretz, January 17, 1986). Or:

Those who initiate meetings between Jews and Arabs are traitors to the nation. This is a destruction… . The Arab nation should not be granted education. If they are allowed to raise their heads, and will not be in the condition of hewers of wood and drawers of water, we will have a problem. The education which is given them is destructive.

So writes Rabbi Yekuti Azri’eli, spiritual leader of Zikhron Ya’akov, in the religious weekly Erev Shabat on September 20, 1985. Mohammed Miari, member of the Knesset, complained to the Minister of Internal Affairs about this article, pointing out that the malady of racism “causes harm to those who bear it no less than to those against whom it is directed.” The Minister of Internal Affairs is Yitzhak Peretz, whom we shall be meeting again. Kol Ha’ir of January 10, 1986, reports, under Shahar Ilan’s by-line, a proposal from Nisim Ze’ev, deputy mayor of Jerusalem, to clear the Arabs out of the Old City. Rabbi Ze’ev says that “the population density in the Old City is a security hazard.” He is just as eloquent when he speaks of the Neve Ya’akov suburb: “Parents are afraid to let their daughters walk outside in the evening, fearing that they may meet an Arab. Arabs live with Jewish women. There is a brothel there with Jewish women and Arab pimps. Such things should be prevented in advance.”

Ten or fifteen years ago, when Shahak was being denounced as an alarmist and a crank, such things were being said “on the fringes.” But ten or fifteen years ago, most Israelis would not have believed that Gush Emunim and Kach militants would have established armed settlements, set up a military underground, elected a deputy to the Knesset, and forged parallel units in the army and the police. As J. L. Talmon, the conservative historian best known for his severe reflections on “totalitarian democracy” during the French Revolution, wrote in what was almost his last letter:

Many among the Orthodox had difficulty accepting the Holocaust within the scheme of Providence and Jewish history, for they could not see the death of more than a million innocent Jewish children as punishment for the sins of the whole Jewish people… . After the Six Day war, however, the Orthodox were much relieved, for now they could argue that the Holocaust had been the “birth pangs of the Messiah,” that the Six Day war victory was the Beginning of Redemption and the conquest of the territories, the finger of God at work.

Talmon was very much a loyalist of the state, emphasizing in this very letter (which was open and addressed to Menachem Begin in the spring of 1980) that he was “not concerned here with the rights of the Arabs regarding whose past and culture I have little knowledge or interest.” But he was a late and probably unwitting convert to the Shahakian view when he wrote:

Any talk of the holiness of the land or of geographic sites throws us back to the age of fetishism.

And:

Is this merely the manifestation of a classically Jewish characteristic, which the Jews may have bequeathed to other monotheistic religions—namely, the need to subordinate oneself to an idea, to a vision of perfection, to an ascetic and ritualistic way of life—instead of treating life as it really is, as did the Greeks, for example, who perceived reality as a challenge and sought to extract from life and nature all the possibilities inherent in them, in order to expand the mind and give pleasure to both body and soul?

We closed our first day of discussion with some differences of emphasis which I believe amount to disagreements of principle. I took, and take, the standard view that derives from Marx’s aperçu that a nation oppressing another nation cannot itself be free. By extension, I argued rather stolidly, Israel’s subordination of nearly three million sullen Palestinians would inevitably debauch Israeli democracy. I called as my witness Danny Rubinstein of Davar, who had written famously about a Jewish longshoremen’s strike in the port of Ashdod where the police had run amok. The bloodied strikers’ leader was interviewed on Israeli television and said indignantly, “What do they take us for? Arabs from the territories?” Here, surely, was a classic illustration of the sort of tension—between poor whites and the “natives”—that Camus had both suffered and described in Algeria.

Shahak, however, detects signs of health and progress in the recent polarization of Israeli Jewish society. These detections are not, as his enemies might suspect, derived from any politique du pire. On the contrary, they arise from his oddly uncynical version of realism. France, he points out, was a cruel colonial power during the Dreyfus Affair. The United States was behaving in a beastly manner in Vietnam during the Watergate exposure. He mentions various other examples, including Warren Hastings in England, who ran India for the East India Company, and Fox, who made the case for Hasting’s impeachment on grounds of extortion, to rebuke my undialectical opening gambit. And he selects, almost perversely, the year 1977 as the one when matters began to improve. Since 1977—the year of Begin’s election—“there has been no further confiscation of Arab private property within pre1967 Israel. And the state of political and religious liberty for Jews has improved enormously.” Shahak allows that things could get rapidly worse in the context of a general or localized war with Israel’s neighbors. But he has a great long-term faith in the operations of democracy. “The sign of victory would be an American-type constitution, which separated church from state and made all inhabitants equal before the law. This would also amount to de-Zionization. Can you imagine an American government confiscating Jewish land for the exclusive use of Christians?” I repress the facetious urge to say yes to this last rhetorical question, and admit his point. A few days later, I see George Bush arrive in Jerusalem fully outfitted with a video crew from his personal PAC and an endorsement from Jerry Falwell. In his address to the Knesset, he chooses to stress the symmetry between Israeli and American values and institutions.

Shahak and I agree to meet next day to debate thornier matters.

EMPLOYMENT OF the word Nazi has an obvious and highly toxic effect on any discussion or argument that involves Israel or the Jews. The merest polemical comparison between certain Israeli and German generals, for example, is enough to ignite torrential abuse and denial. In some cases, the comparison is used demogogically and with the intent to wound. In others, it is invited by the routine, show-stopping denunciation of all criticism of Israel as Nazi or anti-Semitic in inspiration, a routine which does seem designed to arouse the vulgar itch to turn the tables. One may consign this kind of disputation to the propagandists. It remains a fact that within Israel and among Israelis the swastika is a common daub. Instead of being reserved as the ultimate insult, it is freely used to settle arguments about films on the Sabbath, ritual slaughter, and such. It can even be seen on the walls of quarreling religious establishments in the hyper-Orthodox quarter of Mea Shearim in Jerusalem. Amos Oz describes, for instance, in his travelogue In the Land of Israel, a scene in Mekor Baruch:

Here, too, one finds the same slogan that screams in red paint “Touch not my anointed ones” [a quotation from Psalms, meaning, apparently, Do not despoil the innocent children of Israel] and next to it a black swastika. And “Power to Begin, the gallows for Peres”—erased—and then, in anger, “Death to Zionist Hitlerites.” And “Chief Constable Komfort is a Nazi,” “to hell with Teddy Hitler Kollek.” And finally, in relative mildness, “Burg the Apostate—may his name be wiped off the face of the earth,” and “There is no kingdom but the kingdom of the Messiah.”

Oz also notices, as have other writers, the apparent need even of secular Zionist militants for the promiscuous use of Nazi imagery. At one point, arguing with a certain “Z” who expresses his relish at the idea of Israeli conquest, massacre, and enslavement, he asks “perhaps more to myself than to my host”: