Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

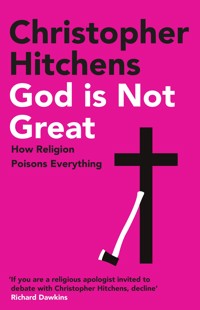

In god is Not Great Hitchens turned his formidable eloquence and rhetorical energy to the most controversial issue in the world: God and religion. The result is a devastating critique of religious faith god Is Not Great is the ultimate case against religion. In a series of acute readings of the major religious texts, Christopher Hitchens demonstrates the ways in which religion is man-made, dangerously sexually repressive and distorts the very origins of the cosmos. Above all, Hitchens argues that the concept of an omniscient God has profoundly damaged humanity, and proposes that the world might be a great deal better off without 'him'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 520

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS (1949–2011) was a contributing editor to Vanity Fair and a columnist for Slate. He was the author of numerous books, including works on Thomas Jefferson, George Orwell, Mother Teresa, Henry Kissinger and Bill and Hillary Clinton, as well as his international bestseller and National Book Award nominee, God Is Not Great. His memoir, Hitch-22, was nominated for the Orwell Prize and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

First published in the United States of America in 2007 by Warner Twelve,an imprint of Warner Books, Inc., Hachette Book Group USA,1271 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020, USA.

First published in Great Britain in hardback in 2007 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Christopher Hitchens 2007

The moral right of Christopher Hitchens to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

987654321

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 227 3

E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 715 2

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House

26–27 Boswell StreetLondon WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Ian McEwanIn serene recollection ofLa Refulgencia

ALSO BY CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS

BOOKS

Hostage to History: Cyprus from the Ottomans to KissingerBlood, Class, and Nostalgia: Anglo-American IroniesImperial Spoils: The Curious Case of the Elgin Marbles

Why Orwell Matters

No One Left to Lie To: The Triangulations of William Jefferson ClintonLetters to a Young Contrarian

The Trial of Henry Kissinger

Thomas Jefferson: Author of America

Thomas Paine’s “Rights of Man”: A Biographygod is Not Great: How Religion Poisons EverythingThe Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the NonbelieverHitch-22: A MemoirMortality

PAMPHLETS

Karl Marx and the Paris CommuneThe Monarchy: A Critique of Britain’s Favorite FetishThe Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and PracticeA Long Short War: The Postponed Liberation of Iraq

ESSAYS

Prepared for the Worst: Selected Essays and Minority ReportsFor the Sake of Argument: Essays and Minority ReportsUnacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public SphereLove, Poverty and War: Journeys and EssaysArguably: Essays

COLLABORATIONS

Callaghan: The Road to Number Ten (with Peter Kellner)

Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question(with Edward Said)

When the Borders Bleed: The Struggle of the Kurds (photographs by Ed Kashi)

International Territory: The United Nations, 1945–95(photographs by Adam Bartos)

Vanity Fair’s Hollywood (with Graydon Carter and David Friend)

Left Hooks, Right Crosses: A Decade of Political Writing(edited with Christopher Caldwell)

Is Christianity Good for the World? (with Douglas Wilson)Hitchens vs. Blair: The Munk Debate on Religion (edited by Rudyard Griffiths)

Contents

One

Putting It Mildly

Two

Religion Kills

Three

A Short Digression on the Pig; or, Why Heaven Hates Ham

Four

A Note on Health, to Which Religion Can Be Hazardous

Five

The Metaphysical Claims of Religion Are False

Six

Arguments from Design

Seven

Revelation: The Nightmare of the “Old” Testament

Eight

The “New” Testament Exceeds the Evil of the “Old” One

Nine

The Koran Is Borrowed from Both Jewish and Christian Myths

Ten

The Tawdriness of the Miraculous and the Decline of Hell

Eleven

“The Lowly Stamp of Their Origin”: Religion’s Corrupt Beginnings

Twelve

A Coda: How Religions End

Thirteen

Does Religion Make People Behave Better?

Fourteen

There Is No “Eastern” Solution

Fifteen

Religion as an Original Sin

Sixteen

Is Religion Child Abuse?

Seventeen

An Objection Anticipated: The Last-Ditch “Case” Against Secularism

Eighteen

A Finer Tradition: The Resistance of the Rational

Nineteen

In Conclusion: The Need for a New Enlightenment

Acknowledgments

References

Index

Oh, wearisome condition of humanity,Born under one law, to another bound;Vainly begot, and yet forbidden vanity,Created sick, commanded to be sound.

—FULKE GREVILLE, Mustapha

And do you think that unto such as youA maggot-minded, starved, fanatic crewGod gave a secret, and denied it me?Well, well—what matters it? Believe that, too!

—THE RUBAIYAT OF OMAR KHAYYAM(RICHARD LE GALLIENNE TRANSLATION)

Peacefully they will die, peacefully they will expire in your name, and beyond the grave they will find only death. But we will keep the secret, and for their own happiness we will entice them with a heavenly and eternal reward.

—THE GRAND INQUISITOR TO HIS “SAVIOR” inTHE BROTHERS KARAMAZOV

Chapter One

Putting It Mildly

If the intended reader of this book should want to go beyond disagreement with its author and try to identify the sins and deformities that animated him to write it (and I have certainly noticed that those who publicly affirm charity and compassion and forgiveness are often inclined to take this course), then he or she will not just be quarreling with the unknowable and ineffable creator who—presumably—opted to make me this way. They will be defiling the memory of a good, sincere, simple woman, of stable and decent faith, named Mrs. Jean Watts.

It was Mrs. Watts’s task, when I was a boy of about nine and attending a school on the edge of Dartmoor, in southwestern England, to instruct me in lessons about nature, and also about scripture. She would take me and my fellows on walks, in an especially lovely part of my beautiful country of birth, and teach us to tell the different birds, trees, and plants from one another. The amazing variety to be found in a hedgerow; the wonder of a clutch of eggs found in an intricate nest; the way that if the nettles stung your legs (we had to wear shorts) there would be a soothing dock leaf planted near to hand: all this has stayed in my mind, just like the “gamekeeper’s museum,” where the local peasantry would display the corpses of rats, weasels, and other vermin and predators, presumably supplied by some less kindly deity. If you read John Clare’s imperishable rural poems you will catch the music of what I mean to convey.

At later lessons we would be given a printed slip of paper entitled “Search the Scriptures,” which was sent to the school by whatever national authority supervised the teaching of religion. (This, along with daily prayer services, was compulsory and enforced by the state.) The slip would contain a single verse from the Old or New Testament, and the assignment was to look up the verse and then to tell the class or the teacher, orally or in writing, what the story and the moral was. I used to love this exercise, and even to excel at it so that (like Bertie Wooster) I frequently passed “top” in scripture class. It was my first introduction to practical and textual criticism. I would read all the chapters that led up to the verse, and all the ones that followed it, to be sure that I had got the “point” of the original clue. I can still do this, greatly to the annoyance of some of my enemies, and still have respect for those whose style is sometimes dismissed as “merely” Talmudic, or Koranic, or “fundamentalist.” This is good and necessary mental and literary training.

However, there came a day when poor, dear Mrs. Watts overreached herself. Seeking ambitiously to fuse her two roles as nature instructor and Bible teacher, she said, “So you see, children, how powerful and generous God is. He has made all the trees and grass to be green, which is exactly the color that is most restful to our eyes. Imagine if instead, the vegetation was all purple, or orange, how awful that would be.”

And now behold what this pious old trout hath wrought. I liked Mrs. Watts: she was an affectionate and childless widow who had a friendly old sheepdog who really was named Rover, and she would invite us for sweets and treats after hours to her slightly ramshackle old house near the railway line. If Satan chose her to tempt me into error he was much more inventive than the subtle serpent in the Garden of Eden. She never raised her voice or offered violence—which couldn’t be said for all my teachers—and in general was one of those people, of the sort whose memorial is in Middlemarch, of whom it may be said that if “things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been,” this is “half-owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

However, I was frankly appalled by what she said. My little ankle-strap sandals curled with embarrassment for her. At the age of nine I had not even a conception of the argument from design, or of Darwinian evolution as its rival, or of the relationship between photosynthesis and chlorophyll. The secrets of the genome were as hidden from me as they were, at that time, to everyone else. I had not then visited scenes of nature where almost everything was hideously indifferent or hostile to human life, if not life itself. I simply knew, almost as if I had privileged access to a higher authority, that my teacher had managed to get everything wrong in just two sentences. The eyes were adjusted to nature, and not the other way about.

I must not pretend to remember everything perfectly, or in order, after this epiphany, but in a fairly short time I had also begun to notice other oddities. Why, if god was the creator of all things, were we supposed to “praise” him so incessantly for doing what came to him naturally? This seemed servile, apart from anything else. If Jesus could heal a blind person he happened to meet, then why not heal blindness? What was so wonderful about his casting out devils, so that the devils would enter a herd of pigs instead? That seemed sinister: more like black magic. With all this continual prayer, why no result? Why did I have to keep saying, in public, that I was a miserable sinner? Why was the subject of sex considered so toxic? These faltering and childish objections are, I have since discovered, extremely commonplace, partly because no religion can meet them with any satisfactory answer. But another, larger one also presented itself. (I say “presented itself” rather than “occurred to me” because these objections are, as well as insuperable, inescapable.) The headmaster, who led the daily services and prayers and held the Book, and was a bit of a sadist and a closeted homosexual (and whom I have long since forgiven because he ignited my interest in history and lent me my first copy of P. G. Wodehouse), was giving a no-nonsense talk to some of us one evening. “You may not see the point of all this faith now,” he said. “But you will one day, when you start to lose loved ones.”

Again, I experienced a stab of sheer indignation as well as disbelief. Why, that would be as much as saying that religion might not be true, but never mind that, since it can be relied upon for comfort. How contemptible. I was then nearing thirteen, and becoming quite the insufferable little intellectual. I had never heard of Sigmund Freud—though he would have been very useful to me in understanding the headmaster—but I had just been given a glimpse of his essay The Future of an Illusion.

I am inflicting all this upon you because I am not one of those whose chance at a wholesome belief was destroyed by child abuse or brutish indoctrination. I know that millions of human beings have had to endure these things, and I do not think that religions can or should be absolved from imposing such miseries. (In the very recent past, we have seen the Church of Rome befouled by its complicity with the unpardonable sin of child rape, or, as it might be phrased in Latin form, “no child’s behind left.”) But other nonreligious organizations have committed similar crimes, or even worse ones.

There still remain four irreducible objections to religious faith: that it wholly misrepresents the origins of man and the cosmos, that because of this original error it manages to combine the maximum of servility with the maximum of solipsism, that it is both the result and the cause of dangerous sexual repression, and that it is ultimately grounded on wish-thinking.

I do not think it is arrogant of me to claim that I had already discovered these four objections (as well as noticed the more vulgar and obvious fact that religion is used by those in temporal charge to invest themselves with authority) before my boyish voice had broken. I am morally certain that millions of other people came to very similar conclusions in very much the same way, and I have since met such people in hundreds of places, and in dozens of different countries. Many of them never believed, and many of them abandoned faith after a difficult struggle. Some of them had blinding moments of unconviction that were every bit as instantaneous, though perhaps less epileptic and apocalyptic (and later more rationally and more morally justified) than Saul of Tarsus on the Damascene road. And here is the point, about myself and my co-thinkers. Our belief is not a belief. Our principles are not a faith. We do not rely solely upon science and reason, because these are necessary rather than sufficient factors, but we distrust anything that contradicts science or outrages reason. We may differ on many things, but what we respect is free inquiry, openmindedness, and the pursuit of ideas for their own sake. We do not hold our convictions dogmatically: the disagreement between Professor Stephen Jay Gould and Professor Richard Dawkins, concerning “punctuated evolution” and the unfilled gaps in post-Darwinian theory, is quite wide as well as quite deep, but we shall resolve it by evidence and reasoning and not by mutual excommunication. (My own annoyance at Professor Dawkins and Daniel Dennett, for their cringe-making proposal that atheists should conceitedly nominate themselves to be called “brights,” is a part of a continuous argument.) We are not immune to the lure of wonder and mystery and awe: we have music and art and literature, and find that the serious ethical dilemmas are better handled by Shakespeare and Tolstoy and Schiller and Dostoyevsky and George Eliot than in the mythical morality tales of the holy books. Literature, not scripture, sustains the mind and—since there is no other metaphor—also the soul. We do not believe in heaven or hell, yet no statistic will ever find that without these blandishments and threats we commit more crimes of greed or violence than the faithful. (In fact, if a proper statistical inquiry could ever be made, I am sure the evidence would be the other way.) We are reconciled to living only once, except through our children, for whom we are perfectly happy to notice that we must make way, and room. We speculate that it is at least possible that, once people accepted the fact of their short and struggling lives, they might behave better toward each other and not worse. We believe with certainty that an ethical life can be lived without religion. And we know for a fact that the corollary holds true—that religion has caused innumerable people not just to conduct themselves no better than others, but to award themselves permission to behave in ways that would make a brothel-keeper or an ethnic cleanser raise an eyebrow.

Most important of all, perhaps, we infidels do not need any machinery of reinforcement. We are those who Blaise Pascal took into account when he wrote to the one who says, “I am so made that I cannot believe.” In the village of Montaillou, during one of the great medieval persecutions, a woman was asked by the Inquisitors to tell them from whom she had acquired her heretical doubts about hell and resurrection. She must have known that she stood in terrible danger of a lingering death administered by the pious, but she responded that she took them from nobody and had evolved them all by herself. (Often, you hear the believers praise the simplicity of their flock, but not in the case of this unforced and conscientious sanity and lucidity, which has been stamped out and burned out in the cases of more humans than we shall ever be able to name.)

There is no need for us to gather every day, or every seven days, or on any high and auspicious day, to proclaim our rectitude or to grovel and wallow in our unworthiness. We atheists do not require any priests, or any hierarchy above them, to police our doctrine. Sacrifices and ceremonies are abhorrent to us, as are relics and the worship of any images or objects (even including objects in the form of one of man’s most useful innovations: the bound book). To us no spot on earth is or could be “holier” than another: to the ostentatious absurdity of the pilgrimage, or the plain horror of killing civilians in the name of some sacred wall or cave or shrine or rock, we can counterpose a leisurely or urgent walk from one side of the library or the gallery to another, or to lunch with an agreeable friend, in pursuit of truth or beauty. Some of these excursions to the bookshelf or the lunch or the gallery will obviously, if they are serious, bring us into contact with belief and believers, from the great devotional painters and composers to the works of Augustine, Aquinas, Maimonides, and Newman. These mighty scholars may have written many evil things or many foolish things, and been laughably ignorant of the germ theory of disease or the place of the terrestrial globe in the solar system, let alone the universe, and this is the plain reason why there are no more of them today, and why there will be no more of them tomorrow. Religion spoke its last intelligible or noble or inspiring words a long time ago: either that or it mutated into an admirable but nebulous humanism, as did, say, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a brave Lutheran pastor hanged by the Nazis for his refusal to collude with them. We shall have no more prophets or sages from the ancient quarter, which is why the devotions of today are only the echoing repetitions of yesterday, sometimes ratcheted up to screaming point so as to ward off the terrible emptiness.

While some religious apology is magnificent in its limited way— one might cite Pascal—and some of it is dreary and absurd—here one cannot avoid naming C. S. Lewis—both styles have something in common, namely the appalling load of strain that they have to bear. How much effort it takes to affirm the incredible! The Aztecs had to tear open a human chest cavity every day just to make sure that the sun would rise. Monotheists are supposed to pester their deity more times than that, perhaps, lest he be deaf. How much vanity must be concealed—not too effectively at that—in order to pretend that one is the personal object of a divine plan? How much self-respect must be sacrificed in order that one may squirm continually in an awareness of one’s own sin? How many needless assumptions must be made, and how much contortion is required, to receive every new insight of science and manipulate it so as to “fit” with the revealed words of ancient man-made deities? How many saints and miracles and councils and conclaves are required in order first to be able to establish a dogma and then—after infinite pain and loss and absurdity and cruelty—to be forced to rescind one of those dogmas? God did not create man in his own image. Evidently, it was the other way about, which is the painless explanation for the profusion of gods and religions, and the fratricide both between and among faiths, that we see all about us and that has so retarded the development of civilization.

Past and present religious atrocities have occurred not because we are evil, but because it is a fact of nature that the human species is, biologically, only partly rational. Evolution has meant that our prefrontal lobes are too small, our adrenal glands are too big, and our reproductive organs apparently designed by committee; a recipe which, alone or in combination, is very certain to lead to some unhappiness and disorder. But still, what a difference when one lays aside the strenuous believers and takes up the no less arduous work of a Darwin, say, or a Hawking or a Crick. These men are more enlightening when they are wrong, or when they display their inevitable biases, than any falsely modest person of faith who is vainly trying to square the circle and to explain how he, a mere creature of the Creator, can possibly know what that Creator intends. Not all can be agreed on matters of aesthetics, but we secular humanists and atheists and agnostics do not wish to deprive humanity of its wonders or consolations. Not in the least. If you will devote a little time to studying the staggering photographs taken by the Hubble telescope, you will be scrutinizing things that are far more awesome and mysterious and beautiful—and more chaotic and overwhelming and forbidding—than any creation or “end of days” story. If you read Hawking on the “event horizon,” that theoretical lip of the “black hole” over which one could in theory plunge and see the past and the future (except that one would, regrettably and by definition, not have enough “time”), I shall be surprised if you can still go on gaping at Moses and his unimpressive “burning bush.” If you examine the beauty and symmetry of the double helix, and then go on to have your own genome sequence fully analyzed, you will be at once impressed that such a near-perfect phenomenon is at the core of your being, and reassured (I hope) that you have so much in common with other tribes of the human species—“race” having gone, along with “creation” into the ashcan—and further fascinated to learn how much you are a part of the animal kingdom as well. Now at last you can be properly humble in the face of your maker, which turns out not to be a “who,” but a process of mutation with rather more random elements than our vanity might wish. This is more than enough mystery and marvel for any mammal to be getting along with: the most educated person in the world now has to admit—I shall not say confess—that he or she knows less and less but at least knows less and less about more and more.

As for consolation, since religious people so often insist that faith answers this supposed need, I shall simply say that those who offer false consolation are false friends. In any case, the critics of religion do not simply deny that it has a painkilling effect. Instead, they warn against the placebo and the bottle of colored water. Probably the most popular misquotation of modern times—certainly the most popular in this argument—is the assertion that Marx dismissed religion as “the opium of the people.” On the contrary, this son of a rabbinical line took belief very seriously and wrote, in his Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, as follows:

Religious distress is at the same time the expression of real distress and the protest against real distress. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, just as it is the spirit of a spiritless situation. It is the opium of the people.

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is required for their real happiness. The demand to give up the illusions about its condition is the demand to give up a condition that needs illusions. The criticism of religion is therefore in embryo the criticism of the vale of woe, the halo of which is religion. Criticism has plucked the imaginary flowers from the chain, not so that man will wear the chain without any fantasy or consolation but so that he will shake off the chain and cull the living flower.

So the famous misquotation is not so much a “misquotation” but rather a very crude attempt to misrepresent the philosophical case against religion. Those who have believed what the priests and rabbis and imams tell them about what the unbelievers think and about how they think, will find further such surprises as we go along. They will perhaps come to distrust what they are told—or not to take it “on faith,” which is the problem to begin with.

Marx and Freud, it has to be conceded, were not doctors or exact scientists. It is better to think of them as great and fallible imaginative essayists. When the intellectual universe alters, in other words, I don’t feel arrogant enough to exempt myself from self-criticism. And I am content to think that some contradictions will remain contradictory, some problems will never be resolved by the mammalian equipment of the human cerebral cortex, and some things are indefinitely unknowable. If the universe was found to be finite or infinite, either discovery would be equally stupefying and impenetrable to me. And though I have met many people much wiser and more clever than myself, I know of nobody who could be wise or intelligent enough to say differently.

Thus the mildest criticism of religion is also the most radical and the most devastating one. Religion is man-made. Even the men who made it cannot agree on what their prophets or redeemers or gurus actually said or did. Still less can they hope to tell us the “meaning” of later discoveries and developments which were, when they began, either obstructed by their religions or denounced by them. And yet—the believers still claim to know! Not just to know, but to know everything. Not just to know that god exists, and that he created and supervised the whole enterprise, but also to know what “he” demands of us—from our diet to our observances to our sexual morality. In other words, in a vast and complicated discussion where we know more and more about less and less, yet can still hope for some enlightenment as we proceed, one faction—itself composed of mutually warring factions—has the sheer arrogance to tell us that we already have all the essential information we need. Such stupidity, combined with such pride, should be enough on its own to exclude “belief” from the debate. The person who is certain, and who claims divine warrant for his certainty, belongs now to the infancy of our species. It may be a long farewell, but it has begun and, like all farewells, should not be protracted.

I trust that if you met me, you would not necessarily know that this was my view. I have probably sat up later, and longer, with religious friends than with any other kind. These friends often irritate me by saying that I am a “seeker,” which I am not, or not in the way they think. If I went back to Devon, where Mrs. Watts has her unvisited tomb, I would surely find myself sitting quietly at the back of some old Celtic or Saxon church. (Philip Larkin’s lovely poem “Church-going” is the perfect capture of my own attitude.) I once wrote a book about George Orwell, who might have been my hero if I had heroes, and was upset by his callousness about the burning of churches in Catalonia in 1936. Sophocles showed, well before the rise of monotheism, that Antigone spoke for humanity in her revulsion against desecration. I leave it to the faithful to burn each other’s churches and mosques and synagogues, which they can always be relied upon to do. When I go to the mosque, I take off my shoes. When I go to the synagogue, I cover my head. I once even observed the etiquette of an ashram in India, though this was a trial to me. My parents did not try to impose any religion: I was probably fortunate in having a father who had not especially loved his strict Baptist/Calvinist upbringing, and a mother who preferred assimilation—partly for my sake—to the Judaism of her forebears. I now know enough about all religions to know that I would always be an infidel at all times and in all places, but my particular atheism is a Protestant atheism. It is with the splendid liturgy of the King James Bible and the Cranmer prayer book—liturgy that the fatuous Church of England has cheaply discarded—that I first disagreed. When my father died and was buried in a chapel overlooking Portsmouth—the same chapel in which General Eisenhower had prayed for success the night before D-Day in 1944—I gave the address from the pulpit and selected as my text a verse from the epistle of Saul of Tarsus, later to be claimed as “Saint Paul,” to the Philippians (chapter 4, verse 8):

Finally, brethren, whatsoever things are true, whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report: if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise, think on these things.

I chose this because of its haunting and elusive character, which will be with me at the last hour, and for its essentially secular injunction, and because it shone out from the wasteland of rant and complaint and nonsense and bullying which surrounds it.

The argument with faith is the foundation and origin of all arguments, because it is the beginning—but not the end—of all arguments about philosophy, science, history, and human nature. It is also the beginning—but by no means the end—of all disputes about the good life and the just city. Religious faith is, precisely because we are still-evolving creatures, ineradicable. It will never die out, or at least not until we get over our fear of death, and of the dark, and of the unknown, and of each other. For this reason, I would not prohibit it even if I thought I could. Very generous of me, you may say. But will the religious grant me the same indulgence? I ask because there is a real and serious difference between me and my religious friends, and the real and serious friends are sufficiently honest to admit it. I would be quite content to go to their children’s bar mitzvahs, to marvel at their Gothic cathedrals, to “respect” their belief that the Koran was dictated, though exclusively in Arabic, to an illiterate merchant, or to interest myself in Wicca and Hindu and Jain consolations. And as it happens, I will continue to do this without insisting on the polite reciprocal condition—which is that they in turn leave me alone. But this, religion is ultimately incapable of doing. As I write these words, and as you read them, people of faith are in their different ways planning your and my destruction, and the destruction of all the hard-won human attainments that I have touched upon. Religion poisons everything.

Chapter Two

Religion Kills

His aversion to religion, in the sense usually attached to the term, was of the same kind with that of Lucretius: he regarded it with the feelings due not to a mere mental delusion, but to a great moral evil. He looked upon it as the greatest enemy of morality: first, by setting up factitious excellencies—belief in creeds, devotional feelings, and ceremonies, not connected with the good of human kind—and causing these to be accepted as substitutes for genuine virtue: but above all, by radically vitiating the standard of morals; making it consist in doing the will of a being, on whom it lavishes indeed all the phrases of adulation, but whom in sober truth it depicts as eminently hateful.

—JOHN STUART MILL ON HIS FATHER, IN THEAUTOBIOGRAPHY

Tantum religio potuit suadere malorum.(To such heights of evil are men driven by religion.)

—LUCRETIUS, DE RERUM NATURA

Imagine that you can perform a feat of which I am incapable. Imagine, in other words, that you can picture an infinitely benign and all-powerful creator, who conceived of you, then made and shaped you, brought you into the world he had made for you, and now supervises and cares for you even while you sleep. Imagine, further, that if you obey the rules and commandments that he has lovingly prescribed, you will qualify for an eternity of bliss and repose. I do not say that I envy you this belief (because to me it seems like the wish for a horrible form of benevolent and unalterable dictatorship), but I do have a sincere question. Why does such a belief not make its adherents happy? It must seem to them that they have come into possession of a marvelous secret, of the sort that they could cling to in moments of even the most extreme adversity.

Superficially, it does sometimes seem as if this is the case. I have been to evangelical services, in black and in white communities, where the whole event was one long whoop of exaltation at being saved, loved, and so forth. Many services, in all denominations and among almost all pagans, are exactly designed to evoke celebration and communal fiesta, which is precisely why I suspect them. There are more restrained and sober and elegant moments, also. When I was a member of the Greek Orthodox Church, I could feel, even if I could not believe, the joyous words that are exchanged between believers on Easter morning: “Christos anesti!” (Christ is risen!) “Alethos anesti!” (He is risen indeed!) I was a member of the Greek Orthodox Church, I might add, for a reason that explains why very many people profess an outward allegiance. I joined it to please my Greek parents-in-law. The archbishop who received me into his communion on the same day that he officiated at my wedding, thereby trousering two fees instead of the usual one, later became an enthusiastic cheerleader and fund-raiser for his fellow Orthodox Serbian mass murderers Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic, who filled countless mass graves all over Bosnia. The next time I got married, which was by a Reform Jewish rabbi with an Einsteinian and Shakespearean bent, I had something a little more in common with the officiating person. But even he was aware that his lifelong homosexuality was, in principle, condemned as a capital offense, punishable by the founders of his religion by stoning. As to the Anglican Church into which I was originally baptized, it may look like a pathetic bleating sheep today, but as the descendant of a church that has always enjoyed a state subsidy and an intimate relationship with hereditary monarchy, it has a historic responsibility for the Crusades, for persecution of Catholics, Jews, and Dissenters, and for combat against science and reason.

The level of intensity fluctuates according to time and place, but it can be stated as a truth that religion does not, and in the long run cannot, be content with its own marvelous claims and sublime assurances. It must seek to interfere with the lives of nonbelievers, or heretics, or adherents of other faiths. It may speak about the bliss of the next world, but it wants power in this one. This is only to be expected. It is, after all, wholly man-made. And it does not have the confidence in its own various preachings even to allow coexistence between different faiths.

Take a single example, from one of the most revered figures that modern religion has produced. In 1996, the Irish Republic held a referendum on one question: whether its state constitution should still prohibit divorce. Most of the political parties, in an increasingly secular country, urged voters to approve of a change in the law. They did so for two excellent reasons. It was no longer thought right that the Roman Catholic Church should legislate its morality for all citizens, and it was obviously impossible even to hope for eventual Irish reunification if the large Protestant minority in the North was continually repelled by the possibility of clerical rule. Mother Teresa flew all the way from Calcutta to help campaign, along with the church and its hard-liners, for a “no” vote. In other words, an Irish woman married to a wife-beating and incestuous drunk should never expect anything better, and might endanger her soul if she begged for a fresh start, while as for the Protestants, they could either choose the blessings of Rome or stay out altogether. There was not even the suggestion that Catholics could follow their own church’s commandments while not imposing them on all other citizens. And this in the British Isles, in the last decade of the twentieth century. The referendum eventually amended the constitution, though by the narrowest of majorities. (Mother Teresa in the same year gave an interview saying that she hoped her friend Princess Diana would be happier after she had escaped from what was an obviously miserable marriage, but it’s less of a surprise to find the church applying sterner laws to the poor, or offering indulgences to the rich.)

A week before the events of September 11, 2001, I was on a panel with Dennis Prager, who is one of America’s better-known religious broadcasters. He challenged me in public to answer what he called a “straight yes/no question,” and I happily agreed. Very well, he said. I was to imagine myself in a strange city as the evening was coming on. Toward me I was to imagine that I saw a large group of men approaching. Now—would I feel safer, or less safe, if I was to learn that they were just coming from a prayer meeting? As the reader will see, this is not a question to which a yes/no answer can be given. But I was able to answer it as if it were not hypothetical. “Just to stay within the letter ‘B,’ I have actually had that experience in Belfast, Beirut, Bombay, Belgrade, Bethlehem, and Baghdad. In each case I can say absolutely, and can give my reasons, why I would feel immediately threatened if I thought that the group of men approaching me in the dusk were coming from a religious observance.”

Here, then, is a very brief summary of the religiously inspired cruelty I witnessed in these six places. In Belfast, I have seen whole streets burned out by sectarian warfare between different sects of Christianity, and interviewed people whose relatives and friends have been kidnapped and killed or tortured by rival religious death squads, often for no other reason than membership of another confession. There is an old Belfast joke about the man stopped at a roadblock and asked his religion. When he replies that he is an atheist he is asked, “Protestant or Catholic atheist?” I think this shows how the obsession has rotted even the legendary local sense of humor. In any case, this did actually happen to a friend of mine and the experience was decidedly not an amusing one. The ostensible pretext for this mayhem is rival nationalisms, but the street language used by opposing rival tribes consists of terms insulting to the other confession (“Prods” and “Teagues”). For many years, the Protestant establishment wanted Catholics to be both segregated and suppressed. Indeed, in the days when the Ulster state was founded, its slogan was: “A Protestant Parliament for a Protestant People.” Sectarianism is conveniently self-generating and can always be counted upon to evoke a reciprocal sectarianism. On the main point, the Catholic leadership was in agreement. It desired clerical-dominated schools and segregated neighborhoods, the better to exert its control. So, in the name of god, the old hatreds were drilled into new generations of schoolchildren, and are still being drilled. (Even the word “drill” makes me queasy: a power tool of that kind was often used to destroy the kneecaps of those who fell foul of the religious gangs.)

When I first saw Beirut, in the summer of 1975, it was still recognizable as “the Paris of the Orient.” Yet this apparent Eden was infested with a wide selection of serpents. It suffered from a positive surplus of religions, all of them “accommodated” by a sectarian state constitution. The president by law had to be a Christian, usually a Maronite Catholic, the speaker of the parliament a Muslim, and so on. This never worked well, because it institutionalized differences of belief as well as of caste and ethnicity (the Shia Muslims were at the bottom of the social scale, the Kurds were disenfranchised altogether).

The main Christian party was actually a Catholic militia called the Phalange, or “Phalanx,” and had been founded by a Maronite Lebanese named Pierre Gemayel who had been very impressed by his visit to Hitler’s Berlin Olympics in 1936. It was later to achieve international notoriety by conducting the massacre of Palestinians at the Sabra and Chatila refugee camps in 1982, while acting under the orders of General Sharon. That a Jewish general should collaborate with a fascist party may seem grotesque enough, but they had a common Muslim enemy and that was enough. Israel’s irruption into Lebanon that year also gave an impetus to the birth of Hezbollah, the modestly named “Party of God,” which mobilized the Shia underclass and gradually placed it under the leadership of the theocratic dictatorship in Iran that had come to power three years previously. It was in lovely Lebanon, too, having learned to share the kidnapping business with the ranks of organized crime, that the faithful moved on to introduce us to the beauties of suicide bombing. I can still see that severed head in the road outside the near-shattered French embassy. On the whole, I tended to cross the street when the prayer meetings broke up.

Bombay also used to be considered a pearl of the Orient, with its necklace of lights along the corniche and its magnificent British Raj architecture. It was one of India’s most diverse and plural cities, and its many layers of texture have been cleverly explored by Salman Rush-die—especially in The Moor’s Last Sigh—and in the films of Mira Nair. It is true that there had been intercommunal fighting there, during the time in 1947–48 when the grand historic movement for Indian self-government was being ruined by Muslim demands for a separate state and by the fact that the Congress Party was led by a pious Hindu. But probably as many people took refuge in Bombay during that moment of religious bloodlust as were driven or fled from it. A form of cultural coexistence resumed, as often happens when cities are exposed to the sea and to influences from outside. Parsis—former Zoroastrians who had been persecuted in Persia—were a prominent minority, and the city was also host to a historically significant community of Jews. But this was not enough to content Mr. Bal Thackeray and his Shiv Sena Hindu nationalist movement, who in the 1990s decided that Bombay should be run by and for his coreligionists, and who loosed a tide of goons and thugs onto the streets. Just to show he could do it, he ordered the city renamed as “Mumbai,” which is partly why I include it in this list under its traditional title.

Belgrade had until the 1980s been the capital of Yugoslavia, or the land of the southern Slavs, which meant by definition that it was the capital of a multiethnic and multiconfessional state. But a secular Croatian intellectual once gave me a warning that, as in Belfast, took the form of a sour joke. “If I tell people that I am an atheist and a Croat,” he said, “people ask me how I can prove I am not a Serb.” To be Croatian, in other words, is to be Roman Catholic. To be a Serb is to be Christian Orthodox. In the 1940s, this meant a Nazi puppet state, set up in Croatia and enjoying the patronage of the Vatican, which naturally sought to exterminate all the Jews in the region but also undertook a campaign of forcible conversion directed at the other Christian community. Tens of thousands of Orthodox Christians were either slaughtered or deported in consequence, and a vast concentration camp was set up near the town of Jasenovacs. So disgusting was the regime of General Ante Pavelic and his Ustashe party that even many German officers protested at having to be associated with it.

By the time I visited the site of the Jasenovacs camp in 1992, the jackboot was somewhat on the other foot. The Croatian cities of Vukovar and Dubrovnik had been brutally shelled by the armed forces of Serbia, now under the control of Slobodan Milosevic. The mainly Muslim city of Sarajevo had been encircled and was being bombarded around the clock. Elsewhere in Bosnia-Herzegovina, especially along the river Drina, whole towns were pillaged and massacred in what the Serbs themselves termed “ethnic cleansing.” In point of fact, “religious cleansing” would have been nearer the mark. Milosevic was an ex-Communist bureaucrat who had mutated into a xenophobic nationalist, and his anti-Muslim crusade, which was a cover for the annexation of Bosnia to a “Greater Serbia,” was to a large extent carried out by unofficial militias operating under his “deniable” control. These gangs were made up of religious bigots, often blessed by Orthodox priests and bishops, and sometimes augmented by fellow Orthodox “volunteers” from Greece and Russia. They made a special attempt to destroy all evidence of Ottoman civilization, as in the specially atrocious case of the dynamiting of several historic minarets in Banja Luka, which was done during a cease-fire and not as the result of any battle.

The same was true, as is often forgotten, of their Catholic counterparts. The Ustashe formations were revived in Croatia and made a vicious attempt to take over Herzegovina, as they had during the Second World War. The beautiful city of Mostar was also shelled and besieged, and the world-famous Stari Most, or “Old Bridge,” dating from Turkish times and listed by UNESCO as a cultural site of world importance, was bombarded until it fell into the river below. In effect, the extremist Catholic and Orthodox forces were colluding in a bloody partition and cleansing of Bosnia-Herzegovina. They were, and still are, largely spared the public shame of this, because the world’s media preferred the simplication of “Croat” and “Serb,” and only mentioned religion when discussing “the Muslims.” But the triad of terms “Croat,” “Serb,” and “Muslim” is unequal and misleading, in that it equates two nationalities and one religion. (The same blunder is made in a different way in coverage of Iraq, with the “Sunni-Shia-Kurd” trilateral.) There were at least ten thousand Serbs in Sarajevo throughout the siege, and one of the leading commanders of its defense, an officer and gentleman named General Jovan Divjak, whose hand I was proud to shake under fire, was a Serb also. The city’s Jewish population, which dated from 1492, also identified itself for the most part with the government and the cause of Bosnia. It would have been far more accurate if the press and television had reported that “today the Orthodox Christian forces resumed their bombardment of Sarajevo,” or “yesterday the Catholic militia succeeded in collapsing the Stari Most.” But confessional terminology was reserved only for “Muslims,” even as their murderers went to all the trouble of distinguishing themselves by wearing large Orthodox crosses over their bandoliers, or by taping portraits of the Virgin Mary to their rifle butts. Thus, once again, religion poisons everything, including our own faculties of discernment.

As for Bethlehem, I suppose I would be willing to concede to Mr. Prager that on a good day, I would feel safe enough standing around outside the Church of the Nativity as evening came on. It is in Bethlehem, not far from Jerusalem, that many believe that, with the cooperation of an immaculately conceived virgin, god was delivered of a son.

“Now the birth of Jesus Christ was in this wise. When his mother, Mary, was espoused to Joseph, before they came together she was found with child of the Holy Ghost.” Yes, and the Greek demigod Perseus was born when the god Jupiter visited the virgin Danaë as a shower of gold and got her with child. The god Buddha was born through an opening in his mother’s flank. Catlicus the serpent-skirted caught a little ball of feathers from the sky and hid it in her bosom, and the Aztec god Huitzilopochtli was thus conceived. The virgin Nana took a pomegranate from the tree watered by the blood of the slain Agdestris, and laid it in her bosom, and gave birth to the god Attis. The virgin daughter of a Mongol king awoke one night and found herself bathed in a great light, which caused her to give birth to Genghis Khan. Krishna was born of the virgin Devaka. Horus was born of the virgin Isis. Mercury was born of the virgin Maia. Romulus was born of the virgin Rhea Sylvia. For some reason, many religions force themselves to think of the birth canal as a one-way street, and even the Koran treats the Virgin Mary with reverence. However, this made no difference during the Crusades, when a papal army set out to recapture Bethlehem and Jerusalem from the Muslims, incidentally destroying many Jewish communities and sacking heretical Christian Byzantium along the way, and inflicted a massacre in the narrow streets of Jerusalem, where, according to the hysterical and gleeful chroniclers, the spilled blood reached up to the bridles of the horses.

Some of these tempests of hatred and bigotry and bloodlust have passed away, though new ones are always impending in this area, but meanwhile a person can feel relatively unmolested in and around “Manger Square,” which is the center, as its name suggests, of a tourist trap of such unrelieved tawdriness as to put Lourdes itself to shame. When I first visited this pitiful town, it was under the nominal control of a largely Christian Palestinian municipality, linked to one particular political dynasty identified with the Freij family. When I have seen it since, it has generally been under a brutal curfew imposed by the Israeli military authorities—whose presence on the West Bank is itself not unconnected with belief in certain ancient scriptural prophecies, though this time with a different promise made by a different god to a different people. Now comes the turn of still another religion. The forces of Hamas, who claim the whole of Palestine as an Islamic waqf or holy dispensation sacred to Islam, have begun to elbow aside the Christians of Bethlehem. Their leader, Mahmoud al-Zahar, has announced that all inhabitants of the Islamic state of Palestine will be expected to conform to Muslim law. In Bethlehem, it is now proposed that non-Muslims be subjected to the al-Jeziya tax, the historic levy imposed on dhimmis or unbelievers under the old Ottoman Empire. Female employees of the municipality are forbidden to greet male visitors with a handshake. In Gaza, a young woman named Yusra al-Azami was shot dead in April 2005, for the crime of sitting unchaperoned in a car with her fiancé. The young man escaped with only a vicious beating. The leaders of the Hamas “vice and virtue” squad justified this casual murder and torture by saying that there had been “suspicion of immoral behavior.” In once secular Palestine, mobs of sexually repressed young men are conscripted to snoop around parked cars, and given permission to do what they like.

I once heard the late Abba Eban, one of Israel’s more polished and thoughtful diplomats and statesmen, give a talk in New York. The first thing to strike the eye about the Israeli-Palestinian dispute, he said, was the ease of its solubility. From this arresting start he went on to say, with the authority of a former foreign minister and UN representative, that the essential point was a simple one. Two peoples of roughly equivalent size had a claim to the same land. The solution was, obviously, to create two states side by side. Surely something so self-evident was within the wit of man to encompass? And so it would have been, decades ago, if the messianic rabbis and mullahs and priests could have been kept out of it. But the exclusive claims to god-given authority, made by hysterical clerics on both sides and further stoked by Armageddon-minded Christians who hope to bring on the Apocalypse (preceded by the death or conversion of all Jews), have made the situation insufferable, and put the whole of humanity in the position of hostage to a quarrel that now features the threat of nuclear war. Religion poisons everything. As well as a menace to civilization, it has become a threat to human survival.

To come last to Baghdad. This is one of the greatest centers of learning and culture in history. It was here that some of the lost works of Aristotle and other Greeks (“lost” because the Christian authorities had burned some, suppressed others, and closed the schools of philosophy, on the grounds that there could have been no useful reflections on morality before the preaching of Jesus) were preserved, retranslated, and transmitted via Andalusia back to the ignorant “Christian” West. Baghdad’s libraries and poets and architects were renowned. Many of these attainments took place under Muslim caliphs, who sometimes permitted and as often repressed their expression, but Baghdad also bears the traces of ancient Chaldean and Nestorian Christianity, and was one of the many centers of the Jewish diaspora. Until the late 1940s, it was home to as many Jews as were living in Jerusalem.

I am not here going to elaborate a position on the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in April 2003. I shall simply say that those who regarded his regime as a “secular” one are deluding themselves. It is true that the Ba’ath Party was founded by a man named Michel Aflaq, a sinister Christian with a sympathy for fascism, and it is also true that membership of that party was open to all religions (though its Jewish membership was, I have every reason to think, limited). However, at least since his calamitous invasion of Iran in 1979, which led to furious accusations from the Iranian theocracy that he was an “infidel,” Saddam Hussein had decked out his whole rule—which was based in any case on a tribal minority of the Sunni minority—as one of piety and jihad. (The Syrian Ba’ath Party, also based on a confessional fragment of society aligned with the Alawite minority, has likewise enjoyed a long and hypocritical relationship with the Iranian mullahs.) Saddam had inscribed the words “Allahuh Akhbar”—“God Is Great”—on the Iraqi flag. He had sponsored a huge international conference of holy warriors and mullahs, and maintained very warm relations with their other chief state sponsor in the region, namely the genocidal government of Sudan. He had built the largest mosque in the region, and named it the “Mother of All Battles” mosque, complete with a Koran written in blood that he claimed to be his own. When launching his own genocidal campaign against the (mainly Sunni) people of Kurdistan—a campaign that involved the thoroughgoing use of chemical atrocity weapons and the murder and deportation of hundreds of thousands of people—he had called it “Operation Anfal,” borrowing by this term a Koranic justification—“The Spoils” of sura 8—for the despoilment and destruction of nonbelievers. When the Coalition forces crossed the Iraqi border, they found Saddam’s army dissolving like a sugar lump in hot tea, but met with some quite tenacious resistance from a paramilitary group, stiffened with foreign jihadists, called the Fedayeen Saddam. One of the jobs of this group was to execute anybody who publicly welcomed the Western intervention, and some revolting public hangings and mutilations were soon captured on video for all to see.

At a minimum, it can be agreed by all that the Iraqi people had endured much in the preceding thirty-five years of war and dictatorship, that the Saddam regime could not have gone on forever as an outlaw system within international law, and therefore that—whatever objections there might be to the actual means of “regime change”— the whole society deserved a breathing space in which to consider reconstruction and reconciliation. Not one single minute of breathing space was allowed.

Everybody knows the sequel. The supporters of al-Qaeda, led by a Jordanian jailbird named Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, launched a frenzied campaign of murder and sabotage. They not only slew unveiled women and secular journalists and teachers. They not only set off bombs in Christian churches (Iraq’s population is perhaps 2 percent Christian) and shot or maimed Christians who made and sold alcohol. They not only made a video of the mass shooting and throat-cutting of a contingent of Nepalese guest workers, who were assumed to be Hindu and thus beyond all consideration. These atrocities might be counted as more or less routine. They directed the most toxic part of their campaign of terror at fellow Muslims. The mosques and funeral processions of the long-oppressed Shiite majority were blown up. Pilgrims coming long distances to the newly accessible shrines at Karbala and Najaf did so at the risk of their lives. In a letter to his leader Osama bin Laden, Zarqawi gave the two main reasons for this extraordinarily evil policy. In the first place, as he wrote, the Shiites were heretics who did not take the correct Salafist path of purity. They were thus a fit prey for the truly holy. In the second place, if a religious war could be induced within Iraqi society, the plans of the “crusader” West could be set at naught. The obvious hope was to ignite a counterresponse from the Shia themselves, which would drive Sunni Arabs into the arms of their bin Ladenist “protectors.” And, despite some noble appeals for restraint from the Shiite grand ayatollah Sistani, it did not prove very difficult to elicit such a response. Before long, Shia death squads, often garbed in police uniforms, were killing and torturing random members of the Sunni Arab faith. The surreptitious influence of the neighboring “Islamic Republic” of Iran was not difficult to detect, and in some Shia areas also it became dangerous to be an unveiled woman or a secular person. Iraq boasts quite a long history of intermarriage and intercommunal cooperation. But a few years of this hateful dialectic soon succeeded in creating an atmosphere of misery, distrust, hostility, and sect-based politics. Once again, religion had poisoned everything.

In all the cases I have mentioned, there were those who protested in the name of religion and who tried to stand athwart the rising tide of fanaticism and the cult of death. I can think of a handful of priests and bishops and rabbis and imams who have put humanity ahead of their own sect or creed. History gives us many other such examples, which I am going to discuss later on. But this is a compliment to humanism, not to religion. If it comes to that, these crises have also caused me, and many other atheists, to protest on behalf of Catholics suffering discrimination in Ireland, of Bosnian Muslims facing extermination in the Christian Balkans, of Shia Afghans and Iraqis being put to the sword by Sunni jiahdists, and vice versa, and numberless other such cases. To adopt such a stand is the elementary duty of a self-respecting human. But the general reluctance of clerical authorities to issue unambiguous condemnation, whether it is the Vatican in the case of Croatia or the Saudi or Iranian leaderships in the case of their respective confessions, is uniformly disgusting. And so is the willingness of each “flock” to revert to atavistic behavior under the least provocation.