Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Modern Tales of the North

- Sprache: Englisch

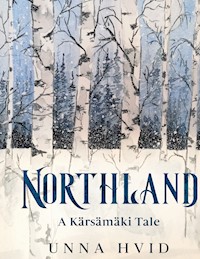

"Matti did not come to Ukko's funeral, although his parents sent a message about it. He could not cope with facing the loss in the form of a coffin, a funeral, the grief of the parents, the support of society for the bereaved. And he did not dare to risk meeting his own parents, his own family. He would stand there as a representative of sin from the south, the sin that had killed his best friend. They would blame him. They would be disgusted at the sight of him. And not for a single moment would they acknowledge his presence." "Northland" is a story about Matti from Kärsämäki in North Ostrobothnia, Finland. An isolated place with a single bus stop on the route between Oulu and Helsinki and a pit stop for drivers who need to refuel on the way to or from their holiday in Lapland. Here, a particularly conservative Christian denomination, Laestadianism, has been strong since the mid-1800s, and Matti was born into one of its congregations. But the world is changing, and so are people. Maybe. "Northland" is based on inspiration from local sources from Kärsämäki, the area's nature, history and folklore and of course from Kalevala, Finland's national epic. "Northland" is the 6th independent story in the series Modern Nordic Folk Tales. Storytelling for adults.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 77

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

EPILOGUE

PROLOGUE

Jemina picks me up at the bus stop in Kärsämäki. It's 3:30 p.m., and if it weren't for the snow, lighting the village up from below, and the big neon sign above the S-Market, it would be pitch dark. The roads are a greyish white and full of ice, but Jemina drives as if on dry black asphalt. Outside, contours of tall firs and dense birch forest rush by. The light mist over the white fields has turned into a night-heavy darkness, which I also feel in my own body.

Jemina shows me around the AIR Frosterus, or Pappila as she calls it, named after the road, Pappilankuja. When we reach the living room, a window flaps in the wind. I can hear the river rushing by like thunder. Jemina closes the window with an irritated click of the tongue while I glance down at the grey-black river below. Smiling, I turn to say something and find that Jemina's gaze is fixed on the other end of the room. My eyes follow her gaze. The door at that end is open, but otherwise there is nothing to see.

Jemina smiles back at me. A little strained, I think, but she has also been sent out in the cold during her Christmas holidays to pick up a stranger at a bus stop and install her in an old rectory outside of Kärsämäki town.

The door at the other end of the room closes with a click. No bang. No slamming. Just a click, as if someone has shut it as quietly as possible. The corners of Jemina's mouth pull to the sides showing no teeth.

"Yes, as I said, sometimes there are creaks and thumps here at Pappila, and the doors can fall shut when there is a draft. Don’t think about it.” Nor would I have done if she had not mentioned it.

It doesn’t take long from when we enter the small thrift shop, until Virpi, the woman working at the office at Pappila, and I are invited to coffee with the ladies who look after the store. The coffee costs 1 euro, but I don't have to pay, because it's not every day we have a visit from a Danish author. We are sitting in the adjoining room, and the ladies have so much to share with me that Virpi has a hard time keeping up with her translation.

One woman tells the story of her grandmother, who once visited one of the old houses with her mother. She walked around for a while, and in the old kitchen she suddenly saw a small, pale, ugly girl staring at her. She ran back to get her mother, but when she came, the girl was gone. But there were footprints in the dust leading to a wall, and on the wall, there was a large burnt stain of soot in the shape of a little girl. All the women around the table shudder uneasily.

A lady with big eyes beneath a quirky hat tells me she had a little sister who once fell into the river. When she saw her little sister underwater, she thought it was Näkki, so instead of helping, she fled in terror. All the children were afraid of Näkki says a slightly younger woman with a large, knitted scarf wrapped many times around her neck. Via the translator app on my phone, I tell the women that the Faroese version of Näkki, the evil water spirit, presents itself to people as a horse, the Swedish version as a beautiful woman and the Danish version as a monster. What does your Näkki look like? But none of them know, as it is a secret creature that no one has seen, I am led to understand.

Unlike the ghost that lives on Pappila, they tell me. The building is a 250-year-old rectory, and the first priest, Johan Frosterus, still lives there. And many people know that. For sure. I see nodding all around the table, and many eyes looking at me to see how I handle that information.

The woman with the hat suddenly recites a poem in Finnish that she herself has written. It's about men who take up too much space on the couch. At least that's how I understand it from Virpi's translation. And then suddenly all the women sing a song in Finnish about all lives being worth a song.

And there is plenty of coffee and different bread, all of which I really must taste, and please take some cake too...

The next morning and many mornings after, I sit out on the dark porch with my coffee. I feel as if in a cocoon in my big polar coat, ski pants and thermal boots. The temperature says -21°. I pull the hood up over my head, sitting at the small table intended for those summer guests who might enjoy a drink here. An ice-cold white wine maybe. But I stick to my café latte in the thermos mug, which keeps one hand warm while the other snuggles in my coat pocket, and I wait for the light to change. In the beginning it is just dark and very quiet. On the other side of the courtyard, I can see the tall firs illuminated from below by the snow. Depending on snowfall and wind, they change color between winter dark green and chalky white snow, from light powder to full cover. Up on the road, a snowplough passes by. At night, a hare has been on the porch, leaving traces in the snow.

Then the light begins to change from black night to blue. The color is a deep dark indigo, almost purple, but clear and luminous. Only the dark firs remain black. Gradually the snow and the sky glow a brighter shade. The blue hour. The light is magical in January. It is as if the night protests against leaving his white bedding. Refusing to leave you as you sit there in the blue darkness. And you also want to stay, just a little longer. But then little by little the blue diffuses, and the morning light prevails and gives everything back its usual hues. The snow turns white, the sky grey or light blue. The day has opened up anew.

I finish my coffee and walk down from the porch and brush the new frosty snow off the kicksleigh. I hurtle down the hill towards the black shingle church as the mist rises above the river and wraps everything in soft shapes of white grey. Down by the church, I look at the full moon still hanging behind the bare black birch trees.

I think of the women's words – every life is worth a song.

Now the cold told a tale to me,

The rain dictated poems,

Another tale the winds brought.

The birds added words,

The treetops speeches…

And now I begin my tale.

It is my desire, it is my wish.

to set out to sing, to begin to recite,

to let a song of our clan glide on, to sing a family lay.

The words are melting in my mouth, utterances dropping out,

coming to my tongue, being scattered about on my teeth.

from Kalevala

CHAPTER 1

Matti was born on a cold and starry night when the green northern lights danced across the sky. The snow was heavy on the roof of the former village school near Kärsämäki, where Matti's parents lived with their large family, of which Matti was number seven. It was early 1965, and there was as yet nothing to suggest that this child would be any different from the first six. Perhaps, if they had been the kind of people who could read the signs, but Mattis's parents were ordinary people who, while strongly faithful, were equally strong in the belief that nothing bad could happen to them. Not as long as the rules were followed to the letter. And Mattis's family were people who followed the rules of the small Laestadian community they belonged to.

In the Kärsämäki, where Matti was born, time had been standing still over old swampy marshlands, tall firs and white birch trunks for a long time. Here, natural areas, large boulders and streams bore the names of Russian soldiers whom local patriots had managed to kill, hanged men, people who lost and died in the forest, drowned children or unhappy women who could not get the one they loved and therefore threw themselves into the river. Everywhere were houses and old log cabins believed to be haunted. The coat of arms told of tribal warfare and burning boats, and its seven flames reminded kärsämäkis that there were seven houses in the city that were bigger than all others.