Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Modern Tales of the North

- Sprache: Englisch

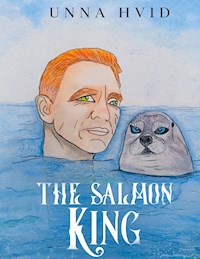

"But The Salmon King was still not entirely satisfied. And when men, whether of jotun descent or human blood, reach out for more than there is to take, good fortune can turn against the brave and arouse not only the wrath of men but also of the Invisible". The Salmon King takes place on the Island of Eysturoy in the Faroe Islands in both the past and present. The story is rooted in the history and folklore of the Faroe Islands and is inspired by old legends, folk ballads, and beliefs, in a modern setting with quota barons and salmon farming. And maybe there are still invisible forces at play in the magical Faroese nature? The Salmon King is the first volume in a planned series of modern tales from all the Nordic countries. The series is also published in Danish and is colourfully illustrated by Unna Hvid in watercolour / mix media.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 59

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

GØTUGJÓGV

TORBJØRN GØTUSKEGG

THE JOTUN RETURNS

THE SALMON KING AND THE SEAL WOMAN

THE HULDU KING

GRÍMUR THE HONOURLESS

VIDAR THE SILENT

THE SALMON IS FREE

GØTUGJÓGV

I have wandered around the village and asked everyone I met, who would be the best to recount the stories of the area. Every villager has recommended her, and now suddenly she shows up of her own accord and sits down next to me on the bench.

From where I sit, I have a view of the whole of Gøtugjógv and most of Gøtuvik. It is so beautiful that the head has no room for thoughts with all that the eyes take in. It has to do with the mountains. They lie in a circle around the three settlements. They are still wintery greenish brown here in early June, as if they were wrapped in old moss. Thousands of sheep and lambs testify to that, when you drive along the narrow roads that wind up and down the mountains between the smaller settlements on Eysturoy. Here you must be careful, not just to stay on the road and not tumble down the cliff sides, but also to look out for the many sheep and lambs that walk on the roads. Fences have been erected along the major thoroughfares, but sometimes a lamb manages to get through the fence, after which the lamb and its sheep mum stand on opposite sides and call out to each other. To one side, the mountains are round and flat. They lie in layers, like cake icing smeared with a knife. On the other side, the tops are notched and angular. On both sides, the mountains are heavily cut from top to bottom by deep gorges that open into the fjord.

Here, three small settlements have grown together over time into one, but the affiliation to one or the other of the settlements lives on. One village has the shop and the gas station, the other has the church and the school. The third has… nothing at all according to an islander I spoke with yesterday. No reason to walk that way, he muttered, living in the middle village, Gøtugjógv himself.

There are long thin cotton clouds hanging under the mountain tops, and in the sky the layered clouds face the sea in shifting shades from stormy dark to sunny bright. Every other moment I look up, and the sea, the mountains, or both have disappeared in the fog. Then it eases a little again. The fog can roll in in minutes and be just as quickly gone again. Contours soften, sounds are muffled in grey cotton wool.

The water curls and shifts towards the bottom of the fjord. A good distance out are 15 large rings in the water circling a fishing boat. It is a facility for salmon farming.

The last couple of evenings I have seen a single Faroese boat, a fourman boat rowing around the fjord for hours. Now it looks like there are quite a few more Faroese boats on their way out into the fjord, and they are bigger, six-man boats, as far as I can see between the grey clouds of fog now pulsating back and forth over the water and getting closer.

As the woman sits down next to me, the fog settles dense and thick around us. She begins to speak, without further ado. Her body is slightly bent forward, due to arthritis perhaps, but it still looks strong, and her face is round and soft under her dark hair, which is skilfully braided. Her eyes are so intense that I must gaze away from her and into the grey to be able to listen.

Once I tune in to her story, all other sounds disappear into the fog.

TORBJØRN GØTUSKEGG

There was a time when a large part of the Islands was covered by forest. People settled on shores and fjords in small settlements isolated from each other and lived off the land, forest, and sea. Together, they cleared the forest and farmed the small plots of land. They helped each other catch fish and whales when the season was right, and they built storage sheds and small wooden houses with grass roofs and connected them with lines for drying fish. The young people of the villages were sent to the mountains to shepherd the sheep, and the elders taught farming skills, housework, handicrafts, and the history of the village to the children.

But the people were not alone on the Islands. Out in the dark, in the forest, on the mountain, in the lakes and on the sea lived other beings who claimed the Islands long before man. Occasionally it came to confrontation between humans and Beings and only rarely for the benefit of humans. Therefore, the village was not just a place to live, it was also a protection against everything Out There that would hurt people. On the side of humans, however, were the Gods, but they were not always to be trusted, nor always strong enough to keep the wicked at bay. Especially the wintertime, when there was only sunlight for a few hours a day and the rest of the day lay in darkness, was unsettling. During the darker days, people gathered in each other's living rooms and had meals together safely in the glow of candles and whale-oil lamps, while listening to those who were best able to tell stories about all that lurked Out There in the darkness and the fog.

In the summer, when the sun shone most of the hours of the day, there was less time to worry, but no fewer dangers. At sea and in the mountains, the fog could suddenly come rolling and envelop people in a matter of minutes, so one lost orientation. At sea you could sail on skerries or move too far out to sea in the long narrow rowboats, and on the mountain, you could fall and break limbs and skulls. Or one could inadvertently get too close to the dwellings of rocks and stones of the Invisibles.

The Invisibles, or huldufólk, were erratic and vengeful if they felt offended. They could push men off cliffs or simply give an honest man a slap in the face or a full beating. The hulde people fished, farmed, and kept sheep, just like the humans. Conflicts could therefore easily arise about ownership of sheep and fishing grounds, or about areas in the mountains that the Invisibles did not want people to get too close to. Then the hulde people took revenge either by violence or by cunning. The hulde people were tall; taller than humans; they wore grey clothes and had dark hair. They should have been easy to recognize, if not for their ability to make themselves invisible along with everything that surrounded them.