Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

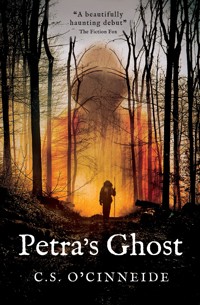

A woman has vanished on the Camino de Santiago. Daniel walks the lonely trail carrying his wife Petra's ashes, along with the damning secret of how she really died. Vibrant California girl Ginny seems like the perfect antidote for his grieving heart, until a nightmare figure begins to stalk them, and Daniel's mind starts to unravel as they are pursued by things he cannot explain.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 432

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Praise for Petra’s Ghost

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Los Angeles Daily News

1 Alto Del Perdón

2 Uterga to Obanos

3 Obanos to Azqueta

4 Azqueta to Torres Del Rio

5 Torres Del Rio to Logroño

6 Logroño to Azofra

7 Azofra to Grañón

8 Grañón to Espinosa

9 Espinosa to Hotel Las Vegas

10 Hotel Las Vegas to Rabé De Las Calzadas

11 Rabé De Las Calzadas to Población De Campos

12 Población De Campos to Calzadilla De La Ceuza

13 Calzadilla De La Ceuza to Portomarín

14 San Paio (8 Miles)

15 Lavacolla (6 Miles)

16 Monte Del Gozo (2 Miles)

17 Carn N’athair

Epilogue Villar De Mazarife to Infinity

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise for

“The kind of rare, immersive read where you feel like you’re breathing the characters’ air and walking in step with them. Part page-turning mystery, part exploration of pain, loss and guilt, part highly original ghost story – the novel defies categorisation and is all the better for it. Atmospheric, brilliantly and engagingly written, I didn’t want the journey to end (although what an ending it is...).”

Sarah Lotz

“Petra’s Ghost follows a spiritual journey along Spain’s ancient Camino de Santiago, or simply ‘the Way’. Vividly realised, eerie, compelling and unputdownable, the novel is haunted at every step – I absolutely loved it.”

Alison Littlewood

“While every story will take you on a journey, it is a rare one that takes you on a pilgrimage. Petra’s Ghost does that: it is a marvellous tale of love, death, and human spirit.”

Francesco Dimitri

“In Petra’s Ghost, C.S. O’Cinneide takes us on pilgrimages literal and figurative. A searching exploration of the weight of the past as well as an increasingly tense supernatural thriller, Petra’s Ghost dives deep into tragedy and loss and comes up clutching gold.”

John Langan

“By turns atmospheric, pulse-pounding, and achingly lyrical, Petra’s Ghost is that rare, exceptional thriller that’s sure to leave you haunted long after the final page.”

Andy Davidson

“Chilling and mysterious, yet pure and sweet, Petra’s Ghost soars from the very first page and accomplishes unforgettable heights. The characters, the imagery, the prose... everything shines. A beautiful journey. A mesmerising novel.”

Rio Youers

“Petra’s Ghost is compelling and haunting, the psychological narrative propelled by the physical journey, as twisty as the path itself, with a vivid and visceral grittiness: you can smell the dust and feel the heat of the pilgrim trail.”

James Brogden

“In prose as clean as bone O’Cinneide tells an unsettlingly elegant tale. By turns horrifying and beautiful, this is a very fine ghost story indeed.”

Angela Slatter

“C.S. O’Cinneide uses the archaic rituals and settings of the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage in rural Spain to tell a very modern ghost story.”

Toronto Star

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Petra’s Ghost

Print edition ISBN: 9781789095609

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789095616

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: October 2020

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Text © copyright by C.S. O’Cinneide, 2019.

Petra’s Ghost by C.S. O’Cinneide first published in English by Dundurn Press Limited, Canada. This edition published by Titan Publishing Group in arrangement with Dundurn Press Limited. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For my Camino brothers, Rob and Michael

And for my husband, Marcus, who makes all journeys possible

Quatuor viae sunt quae ad sanctum Jacobum tendentes, in unum, ad Pontem Regine, in oris Hispanise coadunantur.

Four roads meet at Puente la Reina in Spain and become one route to Santiago.

- CODEX CALIXTINUS, TWELFTH CENTURY

LOS ANGELES DAILY NEWS

Still no trace of American tourist on Spain’s Camino de Santiago

MADRID — Beatrice McConaughey, 32, of Laguna Beach, was last seen August 20 at Villar de Mazarife, in the northwestern Spanish province of León. McConaughey disappeared while walking the Camino Francés, one of the most popular of the pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela, an ancient path that attracts thousands each year. More than six weeks after her disappearance, Spanish police say the investigation remains open.

1

ALTO DEL PERDÓN

The sea is missing.

Daniel stands tall in the early morning on the soaring ridge of Alto del Perdón, searching for a phantom ocean. All he can make out are a patchwork of farmers’ fields. They hover in and out like a mirage beneath the thinning mist settled in the valley below. His navy nylon jacket snaps and billows in the stiff breeze of the exposed hillside. Half a dozen towering wind turbines emit low moans as their massive metal blades turn steadily behind him. At the base of one is a boldly coloured framed backpack, lying open where Daniel has left it at the side of the trail. In his hands he holds a small burlap bag, with Petra inside.

A long line of rusty cut-out men and women are positioned sentinel-like on the ridge, a flat metal monument to all those who, over the centuries, have walked the Camino de Santiago, the five-hundred-mile pilgrimage they call “the Way.” Daniel watches as the silhouettes of the heavy sculpture shudder with the force of the wind. He takes a deep breath of the fresh mountain air. The scent is all wrong to him. Unnatural, without a taste of seawater in it. The rocky outcrops and high altitude, the mist below, they all trick him into thinking he is back in Ireland on the coast of Kerry, where he spent summers as a child by the sea. He and his sister had explored the rugged cliffs above the shoreline for hours, standing far out on the ledges, daring each other.

“Stop being eejits,” his father would bellow from the safety of a lawn chair under the awning of their parked caravan. And Daniel and Angela would trudge back from the sweet seduction of certain death, utterly defeated. Their two older brothers would have deserted them earlier, having the sense to commit their risk taking out of sight of a parent. Maybe he and Angela were idiots after all.

Ever since his first day walking the Camino, climbing through the pass of the French Pyrenees to the Spanish border, Daniel has expected to look down and see the swell of whitecaps, to drink in the tang of brine. The Pyrenees were almost fifty miles ago now, but he still feels the want of salt in the air. He switches the rough brown bag containing Petra to one hand and pulls a stash of sodium-laden beef jerky from his pocket. As if to compensate, he takes a furious bite.

He is less than a week into his pilgrimage through northern Spain, hiking from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port at the border in France to the cathedral in Santiago that houses the shrine of Saint James. The full journey will take him over a month to complete. He travels alongside other pilgrims of varying nationalities and spiritual intent, mostly keeping to himself. Each night after a full day of walking, he checks in at a local albergue. These are modest pilgrim hostels, where five to fifteen euros will get you anything from the top bunk at a large modern municipal, to a hard stone floor of a thirteenth-century monastery. The austerity appeals to his sense of simplicity, or maybe he’s just cheap.

“Sure, no one really believes the bones of Saint James are buried there at Santiago,” his sister, Angela, had told him before he left. “Not even the Catholic Church.”

“Perhaps,” he said, as he looked down at the map of Spain on the coffee table of his living room. The laptop perched next to it on a stack of books as he Skyped his sister from his home in the States. Even so, he had traced one finger along the lonely red dotted line of the Camino, wondering what he might find at the end of it.

One of the turbines groans more loudly, hitting some temporary mechanical resistance. The laboured breath of the sound makes him uneasy. He stuffs the beef jerky back in his pocket.

“Fifty percent of Spain’s energy comes from the wind,” he reminds himself. He’d read it in the guidebook. This is the kind of interesting but ultimately useless fact that seems to always lodge in his brain. Like a piece of popcorn caught in the teeth, and at times just as annoying. Mostly for other people.

“Guess what the longest street in the world is,” he had once asked his eldest brother as he sat with him on the tractor. Daniel had still been far too young to drive it.

“The one where I have to listen to your mouth yappin’ all day.”

The rough burlap bag has a drawstring at the top. Daniel rubs the little braided ropes with his thumb. There is a crinkle inside the coarse material. Plastic. He hadn’t wanted the ashes to get wet if it rained. His backpack was supposed to be waterproof, but he needed to be sure. Petra would have laughed at his practicality. “Always the engineer, planning for contingencies,” she would say. He cannot believe he has put his wife in a zip-lock bag, as if she were a ham sandwich or a dime of weed.

He glances over at the two-dimensional metal figures bent over with their walking staffs and donkeys, medieval pilgrims without the benefit of ergonomically correct backpacks and Thermolite hiking boots from the Outdoor Store. Daniel had bought an old-style pilgrim staff at one of the tourist shops back in France, before he started on the Camino. It had a carved wooden handle and made him look like a prat. He abandoned it in a coffee shop in Zubiri, deciding he could make it to the cathedral of Saint James in Santiago without something to lean on.

The heavy sculpture shudders again. The vibration makes a howling sound, and Daniel feels a tremor echo in his own body. If his granny were here, she’d say a goose just walked over his grave. The old woman had many sayings. Some were old Irish; some she just made up. “These are the words of your ancestors, Daniel,” she would intone, trying to make him pay mind. The land he grew up on had been farmed by Kennedys for almost five hundred years. He couldn’t have escaped his ancestors if he tried.

Trying to shake off the feeling, he shifts from one leg to the other. His new hiking boots feel strange without the steel toe that he normally wears at home when inspecting a job, the familiar density reassuring his foot. Not that he’s been on a job site in a while. As their construction business in New Jersey grew, Daniel and his partner, Gerald, found themselves tied more and more to the office. But of course, he’s all set to sell his half of the firm — or just about. They’d had an offer from a group in New York that would be hard to turn down. There are still papers to sign that Gerald keeps worrying him about. Once that’s done, Daniel’s expected to come back home to Ireland and take over the farm. His father is ready to retire to his lawn chair permanently.

Nothing is keeping Daniel in New Jersey anymore, now that Petra is gone. He’d gone to the States for her and never regretted it, even though he had always felt the pull of the land he grew up on. Those bloody ancestors again. Petra, a child of the North American melting pot, did not have the same ties. Her folks had died in a car crash during her senior year at college. She had no siblings. But her roots were in America just the same, and he had made a life with her there.

Daniel has come to the Camino to spread Petra’s ashes. This is what he needs to do before he can go back to Ireland. This is what he has told his sister, his parents. This is what he has told himself. So he can “move on,” as everyone keeps telling him he must do. He and Petra had always planned to walk the Camino together. Ever since they saw the golden scallop shells and arrows pointing toward the Spanish pilgrimage from France on their honeymoon. He feels that bringing her ashes here serves to keep a promise. Although so many promises remain unfulfilled when someone leaves before you’re ready, like a dinner guest who gets up and walks out during the main course. He could spend a lifetime trying to finish the meal that should have been a future shared with his wife, and the food would rot on the dishes anyway. Somehow, he just can’t bring himself to take away her plate. It’s been over a year now since Petra died and he hasn’t even put their house in Paterson on the market yet.

“When are you comin’ home, Daniel?” his sister, Angela, had asked during one of her weekly phone calls from her apartment in Dublin. His parents were still on the farm at Carn N’Athair in Kilmeedy, but she made the drive out every other weekend to check on them. They were all getting anxious. If Daniel didn’t come home, his father would have to sell out. All those ancestors to be owned by somebody else. His granny would reach out and cuff him from the grave at the sheer shame of it.

“I’ve got some things to do,” he said. He always had reasons. First it was the winding up of the business with his partner. Then it was critical home renovations he needed to make before he could sell. As those jobs dried up he created new ones, increasingly more futile.

“I’m after putting a bidet in the guest bathroom,” he told Angela.

“Correct me if I’m wrong, but how many people when they come over for a cup o’ tea are looking to wash their genitals?” Of course, she had a point. He had ignored it though.

The Camino is his latest effort at procrastination, having run out of rooms to renovate in the house where he and Petra had lived since they were married over ten years ago. Happy years for the most part, until the cancer twisted her into someone he could barely recognize. As gnarled and rake thin as the carved wooden staff he had left behind in the coffee shop. Petra wouldn’t have liked that comparison. She hadn’t been a vain woman, but she’d had her pride. She said the worst part of cancer was turning into something alien, like the dwarfed extraterrestrial in the movie E.T. All she needed to do was hide in a closet full of pinch-faced stuffed animals, she teased the doctors, and they would never find her. Daniel had brought Reese’s Pieces for her the next day in the hospital to continue the joke. She had coughed — her version of laughing in those final weeks.

He should do it here. It makes sense to let the ashes float from the cradle of his hands down into the disappointingly landlocked valley below. An offering to everything he can’t accept. Like having an ultrasound diagnose uterine cancer instead of the baby he and Petra had hoped for. A ruthless surprise that had spread through her body like hot gossip. He’d be angry at God, but he has enough Irish Catholic superstition to believe it might land him in hell or on the receiving end of a lightning bolt. He looks with distrust at the metal pilgrims beside him then scans the sky for storm clouds, on the off chance.

“What do I need with a uterus?” Petra had said. “It’s not a vital organ. Nothing will change.”

But the things that became vital after that changed them both.

Daniel continues to stand looking out on the valley, almost as motionless as the rusty pilgrims on the ridge. The burlap bag remains closed in his hands, its contents secure. Daniel’s right thumb draws the string a little tighter. When he hears the voice from behind him, he jumps as if he has just stuck a wet finger into a light socket.

“I’d stand upwind if I were you.”

He whips around, holding the burlap bag protectively behind his back, looking ridiculous. Like a kid trying to hide a porn magazine from his mother.

A stunted copse of trees grows on the west side of the wind turbines. Someone — a woman, judging by shape — sits alone on a rock there, partly obscured by branches and morning mist. Beside her is one of those cairns you see on the Way, built from small stones the pilgrims leave behind called “intentions,” small rock embodiments of their prayers and purposes. The cairns make Daniel twitch. In Ireland they’re used to mark a place of death, like a car accident, and he can’t help but cross himself every time he sees one. The woman sits there with her face turned away, not acknowledging him.

“Pardon me?” he says, annoyed now that she rattled him so. He starts walking toward her, the bag still in his hands.

She remains turned in profile. Her features seem to morph with the mist and then solidify as he approaches. He stops, confused by the phenomenon. The clearer she becomes, the more everything around them starts to fade. He no longer hears the wind or the turbines. No longer feels the roughness of the burlap bag in his hand. All he can process is the one sense, the sight of her. All he can see is the rich hair tumbling down her back in long waves, natural and free, worn just the way he had always liked. He reaches toward her involuntarily. His fingertips still remember the feel of those rich strands slipping gently through his hands.

“Petra?” He takes a few tentative steps closer. His other senses have returned. He can smell her coconut shampoo now.

The woman doesn’t move. He still can’t see her face, but in her lap her hands are clasped together, a shadowy tube slithering out from the back of her right one. The ever-present IV.

“Petra, is that you?” he whispers, not believing.

The woman doesn’t answer. Her long hair trembles in the wind.

Daniel begins running toward her. She turns her head at the sound of his heavy footfalls then jumps up from the rock and knocks over the cairn. She stumbles and falls on her ass as the intentions spill out all over the ground.

“What the hell?” she yells at him.

He looks at the woman sprawled in the dirt. Her hair is no longer running free down her back in waves, but tied in a high ponytail beneath a pink ball cap. The white stitching on it reads, “Kiss me, I’m smart.” She juts out her lower lip and blows a piece of hair out of her eyes, the result of overgrown bangs.

“What the fuck is wrong with you?” the woman says as she gets up and brushes gravel off the seat of her hiking pants. “You scared the shit out of me.”

He sees the tube now. It hangs not from the back of her hand, but from the hydration bladder in her backpack. Her hair is honey brown, not pale blond like Petra’s. Her face doesn’t even remotely resemble Petra’s. Though her body is toned and fit as Petra’s had been — before she got sick. How could he have mistaken her for Petra? He needs to get a grip. Start wearing his hat more often in the full sun.

“If you plan to attack me, I suggest you get it over with,” she tells him as she zips up the front of her jacket. She reaches for her backpack, which he notices is the smaller-framed duplicate of his own, right down to the colour, bright turquoise. He had wanted black, but the girl at the Outdoor Store had ordered the wrong one, and it had been too late to make an exchange. He had tried to roll it in the mud a few times to make it look manlier, then felt like a git for doing so. His sister had told him he should be too evolved to feel emasculated by a colour.

“What? I mean no.” Daniel watches her pull the hip belt of the pack tight around her middle, adjust the load lifters on both sides. “I thought,” he pauses, “I thought you were after saying something.” He’s not sure of anything now. Maybe she hadn’t said anything. Maybe he had just run at a woman alone in a secluded spot for no reason. The Camino was usually safe, but there had been incidents lately. No wonder she’d shouted at him.

“I said, ‘I’d stand upwind if I were you,’” she says, looking down as she snaps the sternum strap across her chest into place. He wasn’t completely mad then. He had heard her speak after all.

“And why might that be?” Daniel asks. She has managed to annoy him again, despite the fact he’s still shaking.

“So the ashes don’t blow back on you in the wind,” she says, coming toward him, her thumbs hooked in her shoulder straps, standing impossibly close. He can see the faded sprinkle of freckles along the bridge of her nose, smell the dried overripe fruit of a power bar on her breath. “I saw it happen to a guy earlier. He ended up with his son all over his rain pants.”

And with that, she walks away from him, making her way down the ridge, her backpack with the attached white scallop shell bouncing with the sway of her hips. It was an enduring symbol of the Way, that shell, representing one of Saint James’s many miracles. Daniel hadn’t attached one to his own pack, though most did. He had never been good with outward symbols, preferring to play his cards and his purposes close.

He watches the woman slowly sink out of sight, hiking down the other side of the peak. The wind blows his curly black hair into his face when he turns back to look at the valley. She was right about the risk of getting Petra caught in an updraft. This isn’t the right place for her.

Daniel goes back to get his pack, placing the burlap bag carefully inside. He buries it deep at the bottom beneath his guidebook and passport. Then he pulls out the broad-brimmed hat he wouldn’t be caught wearing anywhere else and pulls it down over his unruly windblown hair.

When he stands, he lifts the pack onto his shoulders and feels the weight settle into the strength of his back. But he still carries the heavy doubt of the sea in his mind. Just as he carries what’s left of his wife, unable to accept what happened to her any more than the scent in the air. He wonders whether five hundred miles will be enough to finally lay her to rest, when he was the one who killed her.

The towering wind turbines turn, stoic against a harsh sky, as he follows the path where he has just watched the woman who is not Petra disappear.

* * *

The stones on the way down from Alto del Perdón are slippery with the rain from yesterday. Daniel takes his time picking his way along the trail. He can’t afford to twist an ankle, not when he still has weeks of walking to go. Banked on either side of him are stunted grass and low brush. The occasional huge boulder sits marooned at the side of the trail, as if washed up on the shore of his imagined sea. Gravity rams his toes into the front of his boots. Maybe it is a good thing there is no steel in them.

He is surprised when he comes around a bend and finds her waiting for him, a curious look on her face. Somewhere between amusement and wariness.

“You’re different,” she says, leaning against one of the boulders. It is a statement with a hint of a question.

“How?” Daniel asks her. He stops, braces himself sideways on the hill.

“Just different.”

“The accent,” he says, guessing. Daniel’s accustomed to being outed by the sound of his voice. Most people know as soon as he opens his mouth where he’s from; although, there was a lanky American a few days ago that had thought he was English. That and the fact that the guy never shut up made him want to punch him in his skinny gut.

“Maybe,” she says. Her accent betrays her as well. She is also American. “I thought maybe you were from around here, at first.”

Daniel’s granny had always said he had “the look of the Spaniard,” an Irish pronouncement reserved for those with dark and not-to-be-trusted attractiveness. “The Spanish Armada did some marauding in my country a few hundred years ago,” he tells her. “Left a fair amount of their gene pool about.”

She waits awhile before answering as if weighing the pros and cons of marauding gene pools. “Mind if I walk with you?” she says, apparently deciding in favour of his DNA.

“Free country,” Daniel replies. He’s still a little pissed about how she caught him off guard before. But then again, she did save him from wearing Petra on his jacket.

“My name’s Virginia,” she says, holding out one gloved hand. “People call me Ginny.”

“I’m Daniel,” he says, stepping toward her to return the handshake. He can feel the coldness of her fingers through the thin wool. He forces a smile. Then not knowing quite what to do next, he starts back down the hill.

“Who you got in the bag, Daniel?” she asks, falling in behind him.

“None of your feckin’ business, that’s who I got in the bag.”

“That’s a bit harsh.”

Realizing it probably was, he tries a peace offering.

“Beef jerky?” he asks, holding out the red-and-black cellophane bag.

“No, thanks.”

He puts the hard cured meat back in his pocket. When he pulls out his hand again he rubs it together with the other one, blowing on them. He’s got gloves in his backpack, but he doesn’t bother with them despite the warmth of the autumn sun not yet reaching this side of the valley. He started early this morning while everyone else was still asleep at the albergue, not being a fan of crowds. A result of a rural upbringing with an abundance of space. Also, he’s a bit of an ass before his first cup of coffee. For that reason, it is probably a good thing they don’t talk all the way down. He walks silently, knowing she is behind him. He can hear her ponytail swishing back and forth on the nylon shoulders of her jacket. He remembers the hair he thought he saw flowing down her back up on the ridge, pale and almost to her waist. Wishful thinking is a powerful hallucinogen, he decides.

Soon the topography begins to change, becoming more and more level, fewer rocks, more gravel. The mist is receding with the day. When they round a final bend, the Camino lies in front of them like a length of grey ribbon undulating through plucked orchards and farm fields burnt brown from a summer of hot Spanish sun. They stop for a moment and take in the new scenery, but not for long. There are still eight miles to go to the next albergue, where Daniel plans to spend the night. He’s in good shape but that doesn’t mean walking six hours a day doesn’t make him feel like an old man by evening.

He is nervous at first as they switch to walk beside one another. There is something more personal in this than travelling single file. In time, however, he relaxes into the hypnotic beat of the trail, uninterrupted by speech. Their steps strike a hollow rhythm on the tightly packed earth. Gravel kicked up by their hiking boots the only variation in tempo.

He builds up the courage to steal a glimpse of her. Just a few seconds. He takes in the determined set of her jaw in contrast to the full lips. The little divot on the outside of one slender nostril, betraying the small wildness of a former piercing thought better of. All contrasted with the serious deep-set hazel eyes she had fixed him with back up on the ridge when she had chastised him for frightening her. Ginny said he was different, but he senses she is, too. A woman of contradictions. When she catches him staring, he turns away, embarrassed. Great. Now she’ll think he’s a pervert.

“I’m sorry for asking you about the ashes,” she says.

“No mind,” Daniel tells her. “I reckon I’m just a bit sensitive about it.”

“Just a bit.” She pauses. “Is that why you came on the Camino?”

“I suppose so.”

“Everyone has a story,” she says with a look of understanding. She’s right. Everyone Daniel has met on the Camino seemed to come with a history. He had met a German guy whose daughter had committed suicide. He carried ashes as well. Then there was the middle-aged woman he’d walked with for an afternoon whose husband had left her after thirty years of marriage. She had financed her trip by selling off his favourite football card on eBay.

“Why did you come?” he asks, getting the nerve up to turn and look at her again.

“To pick up guys,” she says. She bursts out laughing when his face starts to redden. He turns away again and keeps walking. Great, he thinks. I’m walking the Camino with a feckin’ comedian.

When they enter the first small village, the two still haven’t spoken again. It’s not due to any ill will, more because each has sensed the other needed some quiet time. There are two vital things a pilgrim needs to learn on the Camino. One is how to prevent blisters and the other is when to shut up. But when they pass a noisy bar full of pilgrims eating breakfast, Daniel breaks the silence to tell her he needs to get a coffee. She waits outside for him.

When he comes back outside with his steaming Styrofoam cup, the street is empty. He looks up and down the road but can’t find her. Then she speaks from behind him and scares the shite out of him for a second time. Where the hell did she come from?

“You notice they are all bars here,” she says.

Daniel wipes his hand where he spilled a bit of the hot liquid on it when she startled him. “The canteens, you mean?” He takes a deep sip of the café con leche, steadying himself. Feckin’ heaven. “I have. Saw two fellas yesterday knocking back shots at seven in the morning with their tea and croissant.”

“I’ve seen the same thing. They’re always so serious though. Like alcoholism is a job they had to show up for when they’d rather stay in bed.”

“You got to admire their work ethic,” he says, taking another sip. This time when she laughs, he smiles instead of blushing.

The two follow the yellow arrows and scallop shells that take them through the small village and keep them on the Camino. Some of the signs and symbols are painted roughly on the walls of old stone buildings. Some are built into the pavement beneath their feet. They meander through village streets and alleyways on a route used by pilgrims for over a millennium. It leads not just to the cathedral in Santiago, but past most of the churches within walking distance. Daniel can see the belfry of one coming up on the right. When he looks up, he can make out a huge nest perched precariously on the top. Every church in Spain seemed to have at least one resident stork. Daniel watches to see if the bird is roosting as he walks by, but the nest is abandoned. If there are any eggs, they have been left unattended.

“Why do you think they brought babies?”

“Huh?” His response to her question is inelegant but authentic. Babies are the last thing on his mind, despite his concern for the eggs.

“Why do you think they always said that the storks brought the babies?” she explains, pointing at the nest.

“They were there,” he says, musing. “It’s always easiest to put the blame on whatever’s close at hand.”

Her eyes flash approval. “I suppose it is. Although not necessarily fair.”

“Life isn’t fair,” Daniel says, and then regrets it. What a downer he is. He tries to recover from looking like a depressing git, even though for the last year he has probably been one. “Did your parents blame the storks?”

“My mother gave me a detailed explanation at the age of four, complete with a discussion of the missionary position and a picture book with fallopian tubes.”

“Impressive,” Daniel says, and he means it.

“I forgot it all by the time I was six and had to have it explained again.”

“Did you remember it after that?” he asks her.

“I can still sketch a vas deferens from memory,” she tells him, smiling.

God, that smile. Playful but challenging. It could set a man off his balance.

“What did your parents tell you about where babies came from?” she asks.

“Nothing,” Daniel tells her, fiddling with the straps of his pack.

“How could your parents tell you nothing?” she asks, pressing him.

“I asked my mother that once,” he says, remembering the conversation. He was a grown man by then. “She told me, ‘You grew up on a farm, Daniel, with the bull let loose on the poor cows in the field each spring. You’d think a clever chiseler like yourself might figure a thing or two out.’” He plays up his mother’s Irish accent. She was from the town and had a different dialect than the rest of them.

“And did you figure it out?” Ginny asks him, completely deadpan.

“I suppose,” he says. “But from my experience, I’d say women are a fair bit different from cows.”

She stares at him now, and he wonders if he has gone too far comparing women to livestock and mimicking his mother with an exaggerated accent like a stock Irish moron. He really needs to get out more.

She continues to fix him with those penetrating grey-green eyes. For a moment, the pupils seem to widen, swallowing up each iris entirely. The wide black circles make him take a step back. Then she’s smiling again, and the healthy hazel returns, the earlier absence of colour a trick of the light.

“Are you interested in a side trip, Daniel?” she says with a raised brow above a perfectly normal eye.

He nods dumbly. Then recovers. “Where to?”

“The site of a massacre,” she says. “It’ll be more interesting than cows.”

2

UTERGA TO OBANOS

The side trail at Muruzábal only adds a couple of miles to Daniel’s planned route. It is not every day you get to see a building associated with the Knights Templar. The Church of Santa Maria de Eunate is twelfth-century Romanesque and octagon shaped, a miniature of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem it was modelled on. The ruins of its external cloister surround the small chapel with crumbling columns and archways. According to the guidebook, the name translates to “Saint Mary of a Hundred Doors.” Daniel counts thirty-three as he approaches. Being Irish, he’s not too offended by the exaggeration. He wants to tell Ginny all this but doesn’t want to bore her with his need to spew facts. Instead he keeps the knowledge to himself. This effort requires a force of will that almost brings the coffee back up his throat.

Although there is a large parking lot in front for tourists, the place looks empty. This is the off-season, and the building looks gloomy and abandoned. It rests at the base of a series of rolling foothills.

“So, where’s the massacre?” he asks Ginny as they cross the main road to the parking lot.

“You know Friday the thirteenth?” she says, not bothering to look both ways as they cross the highway.

“The date or the horror movie?” he asks her.

“The date,” she says. “It was the day the Knights Templar were wiped out by the Catholic Church in a bloody mass execution.”

“Is that why it’s considered unlucky?”

“Sure was unlucky for the knights,” she says. It is not lost on him that she appears to share his enthusiasm for random facts. He wonders if she knows what the longest street in the world is.

“They were the financial arm of the Church, of course.”

“Yes,” she says, nodding, pleased. “Their castles and churches used to be all along the Camino. A place of refuge for the medieval pilgrims, starving half the time and sick. Or injured from attacks by roving bands of thieves.” She does a sweep of the parking lot with her eyes, as if roving thieves may still be an issue, then pushes a stray hair from her ponytail behind one ear. “But the money the Templars held made them too powerful. The pope had to get rid of them.”

“Is that who is buried in the cemetery there, the massacred knights?” Daniel points at the small graveyard on the west side of the church just now coming into view.

“No,” she says.

“Who’d be buried there, then?” he asks.

“The pilgrims who didn’t make it.”

As they approach, they see the site is not entirely deserted. Sitting on a low stone wall between the graveyard and the church is a lone pilgrim. He is dressed much like they are, convertible hiking pants, warm fleece and jacket, and a painter’s cap to keep off the sun. He sports a beard as most men do on the Camino, shaving being one of the first daily grooming habits to go. This man’s red-brown beard is better kept than Daniel’s. He probably had it before he came. The man lifts his arm and waves at them in greeting. His lengthy legs jut out in front of him, one well-worn hiking boot crossed over the other.

“Hola. Buen Camino!” he calls out as they get closer.

“Buen Camino,” both Ginny and Daniel respond, but it is Ginny who continues.

“Está abierto?” she asks him.

“No hablo español,” the man tells her. “Soy holandés.”

“Dutch,” she tells Daniel and then addresses the pilgrim again. “Do you speak English?”

“Yes,” he says, and smiles at her. “Although not as well as German. But much better than Spanish.” He has a Swiss Army knife open, slicing up a red apple. The sharp blade moves deftly in his large hands. On the stone wall he has laid out a checkered linen napkin with a large hunk of dark-skinned cheese and a crusty loaf of bread.

“The church will not open for another quarter hour. We must wait,” he tells them. Daniel eyes the white juicy flesh of the apple. They hadn’t stopped for breakfast, and it’s nearly lunchtime. He tries not to visibly drool.

The Dutchman gestures with an open hand to the food. “Please join me,” he says with a gentleman’s flair. This is something Daniel has noticed about the Dutch, their graceful thoughtfulness. It is a stereotype that becomes the Netherlands, much like tulips.

“Thanks, but we wouldn’t want to be disturbing your meal,” Daniel says, now eying the fresh rind of the cheese as well as the apple. He doesn’t want to take the man’s lunch although he probably shouldn’t have answered on Ginny’s behalf. She doesn’t appear to have noticed, though, as she sits down and tears a good-sized piece of bread from the loaf and pops it into her mouth.

“This is great,” she tells the Dutchman, taking off her gloves. “Very civilized.”

The Dutchman spears a piece of apple with the knife and tips it toward her. She leans in and takes it between her teeth, the shiny blade dangerously close to her lips. Her eyes close in satisfaction. He skewers another piece and offers it to Daniel.

“Please, you are hungry,” he says.

Daniel hesitates for a second more and then takes the fruit from the knife point carefully with his fingers, popping it in his mouth. The tart juice wakes up his tongue, reminding him how thirsty as well as hungry he is. It is time for a break. Slipping off his backpack, he sits down alongside the other two pilgrims.

“Thank you,” he says as the Dutchman cuts off a generous piece of cheese and hands it to him. Its creaminess clings to the sides of Daniel’s mouth. He washes it down with a good swig from his water bottle.

The Dutchman puts down the Swiss Army knife and wipes his right hand on his pants before he extends it. “I am Rob,” he says, before adding theatrically, “the most handsome and intelligent man in the Netherlands.” His wry smile is infectious. Daniel shakes his hand.

“I am Daniel from New Jersey,” he tells him through a mouthful of bread. Rob nods at him without any question in his eyes. People whose first language is not English don’t usually detect the accent. Daniel enjoys the chance to be culturally ambiguous.

“And you?” the Dutchman asks, turning to his other lunch guest.

“I’m Ginny,” she says. “From California.”

“Is this where you learned your Spanish?” Rob asks her.

“Sort of,” she says, cutting off a piece of cheese. “I took a course before I left. Plus, you pick things up after awhile.”

Daniel wishes he had taken a course in Spanish before he left. Two days ago, he tried to order wine in a restaurant. Vino del año meant “young wine,” he was told, the fresh kind they served for drinking early in the year. But he had pronounced it incorrectly, and the insulted waitress told him in English that he had asked for “wine of my butthole.”

“Where did you learn your English?” she asks the Dutchman.

“Oh, from English speakers at my work. I owned once a moving business, but I had to sell and change to a new job. My heart,” he says as he pounds on his chest for emphasis, “was not strong enough for the stress. I had, I am not sure in English.…” The Dutchman pauses for a healthy burp and to search for words. “A go around for my passes,” he says.

“A heart bypass?” Ginny suggests.

“Yes, that is right. A heart bypass. My wife says no more stressful work after this. I listen to my wife.”

“What do you do now?” Daniel asks him.

“I am a miller,” Rob tells him as he pulls another apple from his pack. “We grind wheat for bread in the old way, with a windmill.”

“Wow, that is so Dutch,” says Ginny.

Rob laughs, curling his fist and holding it to his mouth so he doesn’t choke on a bite of apple. “It is,” he admits, as he coughs. When he clears his throat, he reaches into his backpack and pulls out a short fat link of chorizo. He cuts off a slice of the spicy sausage and offers it to Ginny.

“No, thanks,” Ginny says, chewing on a piece of bread before closing her mouth self-consciously.

“The chorizo is very good, Ginny, you should try it,” Rob says, cutting a wedge for Daniel with his knife.

“That’s okay,” she says quietly.

“Are you a vegetarian?” Rob asks her, a bit more perceptive than Daniel. She had refused his beef jerky twice since Alto del Perdón and he hadn’t caught on.

“You’re not a vegan, are you?” Daniel says when she doesn’t respond. “Those people are mad!” He had dated a vegan girl in college once. She had lived off fennel seeds and wheat grass. The only good thing he can remember about her is that she was biodegradable.

“No, I’m not vegan. Just nothing with a face.” Ginny takes a sip from a water bottle she carries. She must have it as a backup for the hydration bladder in her pack. “I eat fish though,” she adds.

“Sure, but fish have faces,” Daniel says.

“Yeah, but they’re ugly faces.”

“This is a shame,” Rob breaks in, looking serious. “There are too many things to enjoy in life to only eat the ugly faces.”

Daniel takes another bite of chorizo, grinning. None of them hear the studded church doors open until a rough voice calls out from them.

“Abierto!” A shrunken elderly Spanish woman pokes her head out as she makes the announcement and then abruptly retreats, like a turtle pulling back into its shell.

Daniel turns to the others after grabbing a last piece of apple. “Ready to go in?”

“Sure,” says Ginny, standing and brushing crumbs from her lap. She doesn’t put her gloves back on. It has warmed up now with the midday. Daniel takes off his hat and stuffs it in his bag.

“I will finish eating,” Rob says, pulling another crust of bread from his backpack, picking up the last piece of cheese. “I have seen it before anyway.”

“You saw it before?” Daniel asks. “But it was closed.”

“I am not good with my English. I mean I have seen inside churches like this before. They are all the same.”

* * *

Ginny and Daniel walk under the main arch of the external cloister and enter through the open doors of the stone chapel. It can’t be more than thirty feet across inside. At the front is a simple raised semicircular sanctuary, where a small table is laid out with a white linen cloth and the tools of the Eucharist. The silver trays of Communion are each adorned with a cross. Daniel looks up to see that the ceiling is ribbed and curved like a stone basket turned upside down. Canned Gregorian chants float up from a speaker on a folding table in the corner, where the elderly Spanish woman sits guarding a stamp pad.

All pilgrims have a “pilgrim passport” that they need to get stamped at intervals along the Way to prove they are walking. Otherwise, they can’t stay in the albergues, which are meant only for people who are undertaking the pilgrimage to the cathedral in Santiago. You can have your passport updated at any of the major stops or attractions. Ginny lays out her passport for the woman but is ignored. The old lady has become distracted by the speaker, trying to adjust a short in the wire that causes the chanting to cut in and out like medieval club music. She flicks a fly from her ancient sunspotted nose as she fiddles with the connection. Ginny gives up and moves on. Daniel doesn’t even bother. He only gets the obligatory stamps each night at the albergue he stays in.

They both light candles at the front. There are real candles here. Not the usual false electric flames in a Plexiglas-lidded box that you activate with a couple of coins dropped in a metal slot. Daniel sits in one pew, Ginny in another. The Gregorian chants have been fixed and now echo again off the curved stone walls. Daniel makes the sign of the cross and lowers his head to pray. It seems appropriate; although, he doesn’t make use of the kneeler, which makes him wonder at his own seriousness. Our Father can’t hear you if your knees aren’t screaming — another of his granny’s sayings. That woman was a peach.

He tries hard for a few minutes, but the prayer won’t come. He can’t even seem to speak to Petra, as he often does at moments like these. He feels cut off from her. He’s not sure whether it is because he is walking with the cute girl across the pew, or because he almost threw Petra off a cliff a few hours ago. He knows he needs a touch of the divine, but his prayers remain empty.

His eyes are still closed when he feels Ginny’s cool breath in his ear. She speaks with a hush.

“Let’s get out of here. This chanting is giving me the creeps.” A smile comes easily to his lips in response, despite the sombre mood of the church and his thoughts.

“Not a fan of the Gregorian monk hit parade?” he asks Ginny, opening his eyes.

“I feel like I’m in The Exorcist.”

“Do you, now?” Daniel says, almost laughing. Talk about inappropriate.

“I do. I’m just waiting for that old lady’s head to spin around.”

This time he does laugh, releasing himself from more tension than he realized he held. He crosses himself again, genuflects quickly toward the altar, and turns to go with her. They are both still smirking a little as they walk up the narrow aisle. The old woman at her table watches them with a furrowed brow of disapproval. As they pass the table, she leans with her fossil-like frame toward them, then flicks another fly in the air.

“Lo estan siguiendo,” she says, and crosses herself. Daniel stops and looks at her. But she folds her arms atop her chest and turns her face away from him as if in protest. He waits a little to see if she will say anything more, but she doesn’t. He doesn’t know what to say to her. His Spanish is so pathetic. Ginny has already gone outside and is not there to translate.

“I’m sorry?” Daniel says to the woman. No reaction. Is she deaf? Or can she not hear him over the chanting. He tries once more with his limited knowledge of the local language. “No entiendo,” he says. I don’t understand.

She turns and looks at him again, repeating what she said before, but more slowly, punctuating each Spanish word with one bent and frighteningly hairy finger in the air.

“Lo estan siguiendo.”

Daniel doesn’t understand any more than he did the first time. His confused look earns nothing more from her but a hand gesture, her index and pinky fingers held up like horns. It is a sign Daniel associates more with 80s heavy metal rock than with the Catholic Church. He assumes she is using it for its original purpose, to ward off the evil eye, rather than to profess her undying love of Iron Maiden. When she turns away again with a huff, he gives up and walks out the door.

Outside, he is surprised to see Ginny about to overtake the top of the first large hill that leads back to the main trail. She has gone on without him. In fact, she must have taken off at quite a clip to get so far in such a short time. Run even. He glances over and sees the low stone wall is unoccupied. The Dutchman has left as well. Nothing remains of his little picnic except a tattered piece of the checkered cloth caught on one of the rougher stones. It flutters in the breeze.