1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Andura Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

An essential classic from beloved English author, E. M. Forster.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

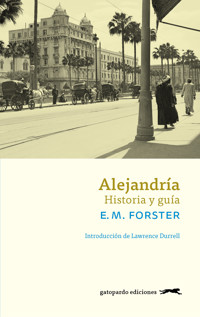

Pharos and Pharillon

Edward Morgan Forster

Contents

9

INTRODUCTION

Before there was civilization in Egypt, or the delta of the Nile had been formed, the whole country as far south as modern Cairo lay under the sea. The shores of this sea were a limestone desert. The coast line was smooth usually, but at the north-west corner a remarkable spur jutted out from the main mass. It was less than a mile wide, but thirty miles long. Its base is not far from Bahig, Alexandria is built half-way down it, its tip is the headland of Aboukir. On either side of it there was once deep salt water.

Centuries passed, and the Nile, issuing out of its crack above Cairo, kept carrying down the muds of Upper Egypt and dropping them as soon as its current slackened. In the north-west corner they were arrested by this spur and began to silt up against it. It was a shelter not only from the outer sea, but from the prevalent wind. Alluvial land appeared; the large shallow lake of Mariout was formed; and the current of the Nile, unable to escape through the limestone barrier, rounded the headland of Aboukir and entered the outer sea by what was known in historical times as the “Canopic” mouth.

To the north of the spur and more or less parallel to it runs a second range of limestone.

10

It is much shorter, also much lower, lying mainly below the surface of the sea in the form of reefs, but without it there would have been no harbours (and consequently no Alexandria), because it breaks the force of the waves. Starting at Agame, it continues as a series of rocks across the entrance of the modern harbour. Then it re-emerges to form the promontory of Ras el Tin, disappears into a second series of rocks that close the entrance of the Eastern Harbour, and makes its final appearance as the promontory of Silsileh, after which it rejoins the big spur.

Such is the scene where the following actions and meditations take place; that limestone ridge, with alluvial country on one side of it and harbours on the other, jutting from the desert, pointing towards the Nile; a scene unique in Egypt, nor have the Alexandrians ever been truly Egyptian. Here Africans, Greeks and Jews combined to make a city; here a thousand years later the Arabs set faintly but durably the impress of the Orient; here after secular decay rose another city, still visible, where I worked or appeared to work during a recent war. Pharos, the vast and heroic lighthouse that dominated the first city—under Pharos I have grouped a few antique events; to modern events and to personal impressions I have given the name of Pharillon, the obscure successor of Pharos, which clung for a time to the low rock of Silsileh and then slid unobserved into the Mediterranean.

11

PHAROS

13

PHAROS

I

The career of Menelaus was a series of small mishaps. It was after he had lost Helen, and indeed after he had recovered her and was returning from Troy, that a breeze arose from the north-west and obliged him to take refuge upon a desert island. It was of limestone, close to the African coast, and to the estuary though not to the exit of the Nile, and it was protected from the Mediterranean by an outer barrier of reefs. Here he remained for twenty days, in no danger, but in high discomfort, for the accommodation was insufficient for the Queen. Helen had been to Egypt ten years before, under the larger guidance of Paris, and she could not but remark that there was nothing to see upon the island and nothing to eat and that its beaches were infested with seals. Action must be taken, Menelaus decided. He sought the sky and sea, and chancing at last to apprehend an old man he addressed to him the following wingèd word:

“What island is this?”

“Pharaoh’s,” the old man replied.

“Pharos?”

“Yes, Pharaoh’s, Prouti’s”—Prouti being

14

another title (it occurs in the hieroglyphs) for the Egyptian king.

“Proteus?”

“Yes.”

As soon as Menelaus had got everything wrong, the wind changed and he returned to Greece with news of an island named Pharos whose old man was called Proteus and whose beaches were infested with nymphs. Under such misapprehensions did it enter our geography.

Pharos was hammer-headed, and long before Menelaus landed some unknown power—Cretan—Atlantean—had fastened a harbour against its western promontory. To the golden-haired king, as to us, the works of that harbour showed only as ochreous patches and lines beneath the dancing waves, for the island has always been sinking, and the quays, jetties, and double breakwater of its pre-historic port can only be touched by the swimmer now. Already was their existence forgotten, and it was on the other promontory—the eastern—that the sun of history arose, never to set. Alexander the Great came here. Philhellene, he proposed to build a Greek city upon Pharos. But the ridge of an island proved too narrow a site for his ambition, and the new city was finally built upon the opposing coast—Alexandria. Pharos, tethered to Alexandria by a long causeway, became part of a larger scheme and only once re-entered Alexander’s mind: he thought of it at the death of Hephæstion, as he thought of all holy or delectable spots, and he arranged that upon its distant shore a shrine should commemorate his friend, and reverberate the grief that had convulsed Ecbatana and Babylon.

15

Meanwhile the Jews had been attentive. They, too, liked delectable spots. Deeply as they were devoted to Jehovah, they had ever felt it their duty to leave his city when they could, and as soon as Alexandria began to develop they descended upon her markets with polite cries. They found so much to do that they decided against returning to Jerusalem, and met so many Greeks that they forgot how to speak Hebrew. They speculated in theology and grain, they lent money to Ptolemy the second king, and filled him (they tell us) with such enthusiasm for their religion that he commanded them to translate their Scriptures for their own benefit. He himself selected the translators, and assigned for their labours the island of Pharos because it was less noisy than the mainland. Here he shut up seventy rabbis in seventy huts, whence in an incredibly short time they emerged with seventy identical translations of the Bible. Everything corresponded. Even when they slipped they made seventy slips, and Greek literature was at last enriched by the possession of an inspired book. It was left to later generations to pry into Jehovah’s scholarship and to deduce that the Septuagint translation must have extended over a long period and not have reached completion till 100 B.C. The Jews of Alexandria knew no such doubts. Every year they made holiday on Pharos in remembrance of the miracle, and built little booths along the beaches where Helen had once shuddered at the seals. The island became a second Sinai whose moderate thunders thrilled the philosophic world. A translation, even when it is the work of God, is never as intimidating as an original; and the

16

unknown author of the “Wisdom of Solomon” shows, in his delicious but dubious numbers, how unalarming even an original could be when it was composed at Alexandria:

Let us enjoy the good things that are present, and let us speedily use the creatures like as in youth.

Let us fill ourselves with costly wine and ointments, and let no flower of the spring pass by us.

Let us crown ourselves with rose-buds before they are withered.

Let none of us go without his part in our voluptuousness, let us leave tokens of our joyfulness in every place, for this is our portion and our lot is this.

It is true that, pulling himself together, the writer goes on to remind us that the above remarks are no elegy on Alexander and Hephæstion, but an indictment of the ungodly, and must be read sarcastically.

Such things they did imagine and were deceived, for their own wickedness hath blinded them.

As for the mysteries of God they knew them not, neither hoped they for the wages of righteousness nor discerned a reward for blameless souls.

For God created man to be immortal, and made him to be the image of his own eternity.

But it is too late. And all racial and religious effort was too late. Though Pharos was not to be Greek it was not to be Hebrew either. A more impartial power dominated it. Five hundred feet above all shrines and huts, Science had already raised her throne.

II

A lighthouse was a necessity. The coast of Egypt is, in its western section, both flat and rocky,

17

and ships needed a landmark to show them where Alexandria lay, and a guide through the reefs that block her harbours. Pharos was the obvious site, because it stood in front of the city; and on Pharos the eastern promontory, because it commanded the more important of the two harbours—the Royal. But it is not clear whether a divine madness also seized the builders, whether they deliberately winged engineering with poetry, and tried to add a wonder to the world. At all events they succeeded, and the arts combined with science to praise their triumph. Just as the Parthenon had been identified with Athens, and St. Peter’s was to be identified with Rome, so, to the imagination of contemporaries, “The Pharos” became Alexandria and Alexandria the Pharos. Never, in the history of architecture, has a secular building been thus worshipped and taken on a spiritual life of its own. It beaconed to the imagination, not only to ships, and long after its light was extinguished memories of it glowed in the minds of men. Perhaps it was merely very large; reconstructions strike a chill, and the minaret, its modern descendant, is not supremely beautiful. Something very large to which people got used—a Liberty Statue, an Eiffel Tower? The possibility must be faced, and is not excluded by the ecstasies of the poets.

The lighthouse was made of local limestone, of marble, and of reddish-purple granite from Assouan. It stood in a colonnaded court that covered most of the promontory. There were four stories. The bottom story was over two hundred feet high, square, pierced with many windows. In it were the rooms (estimated at three hundred) where the

18

mechanics and keepers were housed, and its mass was threaded by a spiral ascent, probably by a double spiral. There may have been hydraulic machinery in the central well for raising the fuel to the top; otherwise we must imagine a procession of donkeys who cease not night and day to circumambulate the spirals with loads of wood upon their backs. The story ended in a cornice and in statues of Tritons: here too, in great letters of lead, was a Greek inscription mentioning the architect: “Sostratus of Cnidus, son of Dexiphanes, to the Saviour Gods: for sailors”—an inscription which, despite its simplicity, bore a double meaning. The Saviour Gods were the Dioscuri, but a courtly observer could refer them to Ptolemy Soter and his wife, whose worship their son was then promoting. For the building of the lighthouse (279 B.C.) was connected with an elaborate dynastic propaganda known as the “As-good-as-Olympic Games,” and with a mammoth pageant which passed through the streets of Alexandria, regardless of imagination and expense. Nothing could be seen in the pageant, neither elephants nor camels nor dances of wild men, nor allegorical females upon a car, nor eggs that opened and disclosed the Dioscuri; and the inscription on the first story of the Pharos was a subtle echo of its appeal.

The second story was octagonal and entirely filled by the ascending spirals. The third story was circular. Then came the lantern. The lantern is a puzzle, because a bonfire and delicate scientific instruments appear to have shared its narrow area. Visitors speak, for instance, of a mysterious “mirror” up there, which was even more

19