Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Luca Caioli

- Sprache: Englisch

When Manchester United re-signed their former youth player Paul Pogba for a world record fee in the summer of 2016, they made a powerful statement. Together with the signing of Zlatan Ibrahimović. It signalled their determination to attract the best players in the world to Old Trafford, despite three seasons of underachievement. In the four years since he had left the Reds, Pogba had blossomed into a midfielder of undoubted world class, his power and dynamism propelling Juventus to a host of club titles and the French national team to within a whisker of winning Euro 2016. With exclusive insights from those closest to the player, Luca Caioli's Pogba is an in-depth portrait of one of modern football's greatest talents.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 269

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

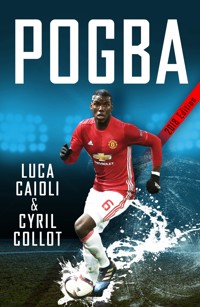

POGBA

About the authors

Luca Caioli is the bestselling author of Messi, Ronaldo and Neymar. A renowned Italian sports journalist, he lives in Spain.

Cyril Collot is a French journalist. He is the author of several books about the French national football team and Olympique Lyonnais. Nowadays he works for the OLTV channel, where he has directed several documentaries about football.

POGBA

2018 Edition

LUCA CAIOLI & CYRIL COLLOT

Contents

1 Son of Yeo Moriba and Fassou Antoine

2 Football, Ping Pong and the City Stade

3 RLS (Roissy-la-Source)

4 The Stadium of Dreams

5 Growing up in Torcy

6 Under the Watchful Eye of the Scouts

7 In Safe Harbour

8 Devils in the Flesh

9 Stolen

10 Manchester, the Home of Football

11 A Band of Brothers

12 Fergie’s Biggest Mistake

13 Juventus Tour

14 Shoooooooot!

15 Light Blue and Dark Blue

16 Golden Boy

17 To Brazil, alongside Messi and Neuer

18 Road to Berlin

19 The Number 10

20 For Sale

21 From Dream to Disappointment

22 Pogback

23 In the Name of the Father, in the Name of the Victims

Acknowledgements

Photos

Chapter 1

Son of Yeo Moriba and Fassou Antoine

The quickest way to trace the origins of the Pogba family is to open an atlas. Put your finger on the African continent; allow it to move west, passing Morocco, Mauritania and finally landing on the Republic of Guinea. This will save you a tiring eight hour flight from Paris to Conakry. However, this virtual journey is far from over. Use your index finger to make an arc from left to right, from the Guinean capital of almost three and a half million inhabitants, turn your back on the Atlantic Ocean to fly over the cities of Kindia and Mamou, carefully follow the borders with Sierra Leone and Liberia before reaching Guéckédou, and bring your journey to an end in Nzérékoré. In no time at all, you have travelled almost a thousand extra kilometres without too much trouble. There are no internal flights or railways across the country from west to east. To get there you must make it along hundreds of kilometres of red dirt tracks by 4×4, avoiding the ruts often concealed by the dust that flies up as bush taxis and overloaded trucks speed past. You will also need to cross towns that may not necessarily appear on your map: Banian, Kissidougou, Macenta and Sérédou.

When you get to Nzérékoré, the country’s third biggest town, the worst is yet to come – around 40 kilometres of roads deemed unsafe, dangerous and often blocked by heavy flooding during the rainy season. Finally, after another hour and a half, a small village comes into view at the end of the road, a sort of balcony overlooking the rainforest.

Fassou Antoine Pogba Hébélamou was born here, in the heart of Forested Guinea, on 27 March 1938. It was in Péla that Paul’s father grew up.

In this landscape at the edge of the world that was hit hard by the Ebola virus between 2013 and 2015 (11,300 deaths in West Africa). Right in the middle of the Mount Nimba nature reserve, not far from the Ziama Massif, home to a formidable variety of flora and fauna, where more than two hundred species, such as duikers (small deer), the favourite meal of lions and leopards, abound. ‘It’s a typical African bush village. It consists of a centre with houses scattered all around. The inhabitants work in the fields; they are known in the region as “Forestiers”’, says Alban Traquet, the only European journalist to have made the real-life journey to Péla for a report on the origins of the Pogba family for L’Équipe in March 2017. ‘It’s a no man’s land, one of the most remote and poorest places in the country. Nor is it a region spared from hardship: in addition to the ravages of Ebola, it is almost completely cut off from the outside world for eight months a year due to heavy rains.’

Although the official language is French, Guinea is home to almost twenty dialects. Diakhanké, Malinké and Susu are the most widely spoken. In Péla they speak Guerzé, also known as Kpelle. This language, which binds the village’s 5,600 inhabitants, is shared with their close neighbours in Liberia and spoken throughout the south of Guinea, particularly in the region of the Nzérékoré prefecture. It is from this dialect that one of the most famous surnames of the 21st century comes: ‘Pogba is not their real family name,’ reveals Alban Traquet. ‘They were originally known as “Hébélamou”. The name “Pogba” was attributed to Paul’s grandfather because he was particularly influential in the village. In the Guerzé language it means “reverential son”, or someone who is respected and listened to by his family. Since then, the whole family has kept the name.’

Fassou Antoine first arrived in Paris in the mid-1960s, when he was in his thirties. Guinea was undergoing drastic upheaval at the time. A French colony since 1891, it obtained its independence in October 1958 after opposing the referendum announced by General Charles de Gaulle, who wanted the country to be part of a new French Community. The response was scathing: in the following month, France began its withdrawal from the country, leaving the Guineans deprived of military and financial aid, as well as many civil servants, including teachers, doctors and nurses. It was at this time that Fassou Antoine packed his bags to settle in the Paris region, where he began a career in telecommunications, before becoming a teacher at a technical high school. The rather poised and discreet young man was passionate about the round ball. This passion had developed at an early age, and stayed with him over the years. He was a keen fan of the ‘Syli’, the Guinean national team, and, since arriving in France, he had been involved in the founding of the Africa Star de Paris football club, which brought the local Guinean community together until 1990.

The remoteness and inaccessibility of Péla meant that visits home to his childhood village were rare. He did return in the late 1980s, however, when he spent time with his younger brother Badjopé and one of his sisters, Kébé: ‘God had not blessed my brother Fassou with children. He was living in France and was fifty, so he returned home to sacrifice a ram in the hope of finding fertility,’ Kébé told the journalist Alban Traquet when he visited the village. ‘He then left again for Conakry in search of a romantic relationship.’

This sacrificial ceremony therefore marked the starting point for the meeting between the Christian, Fassou Antoine and the future mother of Paul Pogba, a Muslim woman in her twenties named Yeo Moriba. Like her future husband, she was from Forested Guinea, but from the village of Mabossou, located about 100 kilometres north of Péla. The daughter of a civil servant, she came from a family of well-known figures: her great uncle, Louis Lansana Beavogui was the Prime Minister of Guinea between 1972 and 1984 and even temporarily occupied the position of head of state after the death of the illustrious Sékou Touré, but he was quickly overthrown and imprisoned following a military coup. There was also, to a lesser extent, her cousin, Riva Touré, who had had a brief career as a footballer in Guinea and worn the prestigious shirt of AS Kaloum Star. The Conakry club had done well for itself by winning the national league a dozen times. Yeo Moriba, a cheerful and determined young woman, also had a soft spot for the country’s number one sport, which she practised diligently. She was doing well for herself and was on the point of being named captain of the national women’s team.

Despite the age difference, the couple had a number of things in common thanks to their passion for football and background in Forested Guinea. This was only the beginning, Yeo was soon expecting twins! The ram sacrifice had not been in vain. Yeo Moriba gave birth to two beautiful boys, Florentin and Mathias, on 19 August 1990. The small family would spend two years in the port city of Conakry before leaving the Guinean capital to settle permanently in France, about 30 kilometres to the south-east of Paris, in Roissy-en-Brie.

A former hunting ground with 150 hectares of forest that it shared with the neighbouring town of Torcy, the commune in Seine-et-Marne was undergoing profound change and development. The census takers had their work cut out over twenty years: the population had risen from 500 to almost 20,000 inhabitants in 1992. In other words, the wheat fields had given way to buildings of all kinds by the time the couple and their two children took possession of an apartment in the Le Bois-Briard development in a peaceful area to the north-east of the city. The family grew a year later thanks to the arrival of a third son: Paul Labile Pogba, who was born on 15 March 1993. Like all local children, he came into the world at the maternity unit in Lagny-sur-Marne hospital, about ten kilometres from his home.

Back in Guinea, the news of the birth of a new member of the Pogba family spread very quickly. Rosine, one of the maternal aunts who had also settled in the capital, would be one of the first to visit the little miracle. She remembers this of her stay in France: ‘The twins were there and Paul was tiny. He was six months old. The day I arrived, I held him in my arms and put some big sunglasses on him for a photo,’ she says, showing an image of her giving a bottle to the newest member of the family, who is all smiles. ‘I can say that he was born with success and that he had it in his blood. This was the blessing I gave to his mother.’

In the villages of Mabossou and Péla, Paul would be seen only in snapshots sent from France. Although Yeo Moriba kept close ties with her country, where she now owns a luxury house given to her by her youngest son in the Kipé neighbourhood of Conakry, his father, Fassou Antoine, gradually became more distant. He never returned to his native village after the famous ram sacrifice in 1989 and was never able to officially introduce his three sons: ‘But that did not stop the creation of a link and in Péla a huge portrait of Paul has been painted in the town hall,’ reports Alban Traquet. ‘It’s a way of thanking him for his many gifts. He has given the village a sound system, a generator and a flat screen for the video club. He also funded the sending of a hundred 50 kg bags of rice to help the needy. He and his brothers sent two sets of FC Pogba printed shirts for the young people of the village in the colours of Manchester United and AS Saint-Étienne, where Florentin plays.’

Of course, they all hope to see Paul come to the village of Péla in the flesh one day and not only just to make it as far as the capital Conakry, as he did in 2011. This one visit to the country of his ancestors nevertheless left its mark on him. He will never forget what he saw on the streets of the capital. This journey of initiation carried out in the year he turned eighteen gave him a close-up view of suffering and helped him understand how lucky he had been. It also taught him to share and measure his happiness. ‘Over there, they laugh, they play football and they have nothing, but they seem happier than we do, Europeans who have everything,’ he would say in the summer of 2016. ‘You’re black, they’re black but they know you’re not from there. All that helped me grow.’

In the mid-1990s, one event marked the childhood of Paul Pogba. At that time, he was still far from imagining what awaited him. Too young to see into his future. Too young to remember his family’s heartbreak. When he was only two years old, his parents decided to separate. Fassou Antoine kept the apartment at Le Bois-Briard. Yeo Moriba moved a little further away but still in the town of Roissy-en-Brie. With her three children by her side, she went to live in the neighbourhood known as La Renardière.

Chapter 2

Football, Ping Pong and the City Stade

It was always the same. Her children never knew when to stop. Yeo Moriba had to raise her voice: ‘Hey, boys! It’s time to come in! Hurry up, it’s dark and you’ve got to go to bed,’ she shouted from her window on the twelfth floor of the tall white tower, using her deep, strident voice to make herself heard through the branches of the large pine trees that concealed the playground a hundred metres or so below. If she had not intervened that night, her three sons would have kept on playing until dawn. Florentin, Mathias and Paul eventually finished their match, picked up their ball and ran up alleyway no.13 at the Résidence La Renardière.

Paul was seven years old; Mathias and Florentin were ten. The City Stade had just been built at the end of the playground, along the railway track. It quickly became a rallying point for all the local kids. Since the 1970s, La Renardière had been home to fourteen blocks of varying sizes. Several buildings are scattered across the large landscaped estate among four large towers with up to thirteen floors. It was in one of those, the closest to Avenue Auguste Renoir, that Yeo Moriba had settled with her family five years earlier.

In the modest uncluttered apartment, she brought up her three sons and two nieces on her own: ‘They were the daughters of her big sister,’ explained a close friend of the family. ‘They were called Marie-Yvette and Poupette. They’re in their thirties now. One lives in England and the other in the south of Paris. They played the role of big sisters and sometimes mothers to the boys, preparing meals for them or taking Paul to the Pommier Picard School across the street.’

To be able to provide for everyone, Yeo Moriba took on several jobs: she worked as a chambermaid in a hotel, a cashier at a supermarket and an employee at an aid association for the handicapped. She struggled to ensure that her children would not go without: ‘I made a lot of sacrifices. I worked morning and night to support them, so they wouldn’t be picked on by their schoolmates, would be happy and could go on holiday,’ she tells the journalists who come to interview her in her new well-to-do apartment in Bussy-Saint-Georges (about 30 kilometres from Roissy-en-Brie), in which the living room looks more like a museum with its carefully arranged newspaper clippings and photos.

The boys were inseparable. Paul could always be found with the twins. ‘They were like the Three Musketeers. The twins really mollycoddled their younger brother. They were always as thick as thieves,’ explains Henri, a long-time resident of the neighbourhood who we meet while crossing the car park. Paul had a strong character and was a real showman. He liked to dance, sing and play the clown. He soon came up with nicknames for the whole family. Starting with himself. He christened himself ‘La Pioche’ (The Pickaxe). ‘There was an Ivorian actor in a TV series, Gohou Michel, who always said “La Pioche, il va piocher le village” [The Pickaxe, he’s going to use his pickaxe in the village], ‘Pogby La Pioche.’ I liked it so even my mother started calling me “La Pioche”,’ Paul said in 2016. Next came the turn of his two brothers: Florentin, the craziest, would be ‘Red Bull in his blood,’ then ‘Flo Zer’ and then just ‘Le Zer.’ Mathias, who ‘had a back like a gorilla’, would be simply ‘Le Dos’: The Back.

Le Zer, Le Dos and La Pioche soon carved out a reputation for themselves in the neighbourhood. At the end of the school day, they would take possession of the small pitch and entertain themselves while perfecting their technique to impress their friends: keepie uppies with their left foot, right foot, and head, dribbling and firing shots towards the goal. Champions in the making!

At the City Stade, where the handrails have been repainted bright red and grey and the artificial pitch replaced by concrete, they now play both basketball and football. Surrounded by a dozen kids shouting and running in all directions, two local teenagers, Bryan and Kévin are quietly shooting hoops to the rhythm of the beats emanating from a small speaker. They know the Pogbas by reputation. One of the two kids points to a large white wall that had been home to a huge portrait of the future French international for more than a year: ‘It was painted by the local kids but then covered up. But there’s still a poster of Paul on the landing of his old apartment. Proof that he was here.’

However, our two NBA aficionados know nothing of the football tournaments that saw the local kids face off during the school holidays in the early 2000s. Matches at the social centres saw players from La Renardière challenge other residences such as ‘50 Arpents’, ‘Bois-Briard’ and ‘La Pierrerie’. ‘Games were held over two legs, home and away,’ explains Yoann, in his thirties, once a young footballing hopeful now working as a chauffeur. ‘You should have seen the level! The winner was the first to ten. In the early days, Paul waited quietly behind the handrail, watching his brothers intently.’

But he would not remain a spectator at these five-a-sides for long. His brothers soon threw him in at the deep end: the ‘City’ would be his first training academy. ‘We were happy he wanted to play with us and not mess about with the kids his own age,’ explain his two brothers. ‘It helped give him character.’

The three Pogbas were given offensive positions. Mathias and Florentin, also nicknamed the Derrick brothers after the cartoon Captain Tsubasa, played on the wings. Paul was put in the central midfield. No prisoners were taken in this rough street football; the boys played right up against the walls and would even hit each other during one-on-one’s. Paul was often knocked to the ground. Whenever a tear began to appear in the corner of his eye, he was immediately called to order: ‘Stop crying and play!’ his brothers commanded. As the matches went on, he began to toughen up. He resisted better, learned to fight his own corner, became stronger and made progress.

The kid had character alright, as well as a marked taste for competition, something it was said he got from his father, Fassou Antoine. He did not like to lose and was lucky because La Renardière often came out the winner of these local matches. But it was not just about football. Whenever he lost at cards at home or at the PlayStation, he would get himself into a real state. He wanted to play over and over again to compete with his brothers. It was the same when he discovered table tennis, thanks to Florentin and Mathias. Luckily, the club was just five minutes’ walk from the residence. At the time there was even a shortcut across waste ground to avoid Avenue Eugène Delacroix.

The Salle Jacques Rossignol, built from beige and blue sheet metal, is set back from the road, just behind a small dirt car park. At the time, the US Roissy Table Tennis club had just taken over the space left vacant by a bowls club. It was the perfect spot to line up almost a dozen tables with the space behind them to allow the players to move around comfortably. In 1999, Patrick Sembla, a former professional and the life and soul of the club where he has been coaching for more than twenty years, remembers the arrival of the Pogba twins, followed very quickly by the youngest member of the family: ‘They were always accompanied by their two big “sisters”, who would drop them off in the late afternoon and then collect them around 8.30pm. Paulo, as I nicknamed him, wanted to do everything Mathias and Florentin did. He was a smart kid. A nice kid, always happy and motivated. He tried to copy his brothers in every way. He tried and tried again and again until he got there. He was extremely gifted and clearly had the mental, physical and tactical ability to succeed. He would learn in three minutes what it took others a year to assimilate. He had all the qualities to become a champion, in table tennis or in any other sport, for that matter.’

In table tennis, it would be the twins who would win the prizes, however. Florentin became champion of Seine-et-Marne and Île-de-France. Mathias did even better and became French Under-11 champion. ‘They were so much better than everyone else that they shared out the wins and were happy to knock balls around in the finals,’ explains Sembla. ‘Sometimes one would win and then the next time the other. They had this determination to be the best, whatever the sport. You could feel their will to win.’ One of Paul’s best memories is of a tournament in Roissy-en-Brie where he was playing in a higher age category and could play against the rest of the family for once. Wearing the light blue shirt of US Roissy TT, the Pogbas pulled off an incredible family victory: ‘Flo 1st, Mathias 2nd and Paulo 3rd.’ Paul can only have been seven or eight but he was already ranked among the three best table tennis players in Seine-et-Marne in the Under-11 age group.

Despite his promise, Paul eventually said goodbye to table tennis aged nine: ‘His brothers had just been selected among the best young table tennis hopefuls in Île-de-France and Paul probably didn’t want to carry on playing the sport on his own in Roissy. Florentin and Mathias wanted to go as far as they could in table tennis but in the end it became tough for them because they also had ambitions in football. Within a year they had all stopped,’ says a regretful Patrick Sembla, who keeps several photos of the Pogba brothers on his phone as a souvenir. In one of these, the coach is flanked by the twins on the day Mathias won the title of French champion. In another, Paul is wearing a navy and white t-shirt at the front of a group of about twenty kids. As always, his brothers are not far away, just behind him wearing the club shirt. ‘I’ve got other ones but I prefer to keep them for myself. Paul is so concerned about his look and appearance that he would hate me if I made them public.’

In the end, Paul decided to devote himself entirely to his favourite sport but presumably has no regrets about the time he spent at US Roissy Table Tennis: ‘Table tennis is a sport that requires a lot of concentration. If you get upset you lose your match. That helps me a lot today.’ The insatiable competitor surrendered his weapons without ever managing to beat Mathias or Florentin. They were too good for him but were still careful to look after their little brother: ‘Back then, whenever they received a cheque or some money for winning a tournament, they bought me a pair of shoes. I always told them I would pay them back.’

Chapter 3

RLS (Roissy-la-Source)

It is a Wednesday like any other at the Stade Paul-Bessuard. And yet as soon as you go through the little gate, for some strange reason it feels like the first weekend of the summer holidays. At the USR, the Union Sportive de Roissy, kids are running back and forth like cars on the A7 Autoroute du Soleil from Paris to the beaches of the south during the summer exodus. The hustle and bustle is constant, sometimes causing traffic jams in the narrow alleyway that borders the new artificial pitch and runs alongside the dressing rooms and office. Some of the kids greet each other with a tap of the fist and a ‘Check mon pote’, others run after each other shouting ‘You can’t catch me!’ while others still chat about their morning at school. One takes refuge in the secretary’s office to read a love letter away from prying eyes. He is quickly chased out by the secretary herself, Martine: ‘Shoo, you can’t be in here!’ He is swallowed up by the influx of young footballers with a colourful mix of shirts and origins who give this town in Seine-et-Marne its character. A little black kid wearing a Real Madrid shirt returns to his mother, who is armed with a large pushchair in which his little sister is taking a nap. ‘Say goodbye and don’t forget to ask your coach why you didn’t play last weekend!’ The little boy does as he is told and runs off, teasing another kid who is not allowed a snack during Ramadan as he goes. ‘Do you want some?’ he mocks a teammate wearing full PSG strip while waving a piece of cake under his nose. A few yards away, the instructors do not bat an eyelid. They are too busy carrying out a head count and dishing out invitations to play in matches that weekend, like sweets. The wind catches these invitations as they fly away over the offices while the kids look on with amusement. Their run comes to an end on the other side beneath the covered stand that overlooks the main pitch. On Wednesdays its turf is used to teach the youngest children the basics. You could spend hours there just admiring the show. A tall, slender black man with a fine white goatee beard and an Olympique Lyonnais cap is fussing around a dozen children who cannot be more than five at most. Some of them are wearing the club’s socks, recognisable by their wide blue and white stripes. They are all wearing bibs that are far too large for them. They are so small and light the ball seems to weigh them down like an anvil. They struggle to move, so much so that their instructor is constantly interrupting them and gesturing with his arms. ‘The greens are going that way. Why are you shooting in this direction?’ a man in his fifties asks a nervous little blond boy. A few seconds later, he restarts the game: ‘Play!’ A mother takes advantage of the interruption to retie her son’s laces.

The instructor cuts such an imposing figure that it is hard to take your eyes off him. He dispenses so much good advice that he could be a wise village elder: authoritarian when necessary but still keeping an eye out for the slightest graze or mishap. It is not surprising that he knows how to deal with the kids. Mamadou Diouf has been training coaches in Île-de-France and the district for more than twenty years. He is also the technical manager of the football school: ‘US Roissy is a family club,’ he explains after his session. ‘95 per cent of our players live in the town. There’s a strong social cohesion here. In 2010, we opened the club up to children aged four because that allowed us to better target the kids and to teach them ball control more easily. This is reflected in their progress. For example, in the Under-9 category our boys are already capable of 30 keepie uppies with both feet and fifteen with their heads. That bears fruit and now we’re almost a victim of our success. Even more so when people find out that Paul Pogba came through here. We have almost 550 players. You can’t imagine how many want to be like him and copy his haircut! It’s great marketing for the club! Some parents think if they sign their kid up with us they’ll be just as successful.’ It is not hard to imagine the scene: proud fathers hoping that one day their son’s shirt will be carefully folded in a frame hanging on the wall of the little locked office that serves as a makeshift museum for US Roissy. Hanging next to the red and white PSV Eindhoven shirt printed with the number 2 of Nicolas Isimat-Mirin and relics of all three Pogba brothers. A light blue shirt with the unlikely number 99 that belonged to Mathias, a green AS Saint-Étienne jersey with Florentin’s number 19, and the black and white shirt worn by Paul when he made his debut for Juventus. The shirt is genuine and signed. The local star even took the trouble to write a message in red felt tip pen across the white printing of his number 6: ‘To my first dream club, Roissy-en-Brie.’

Paul joined the club in September 1999. He was following in the footsteps of his two brothers, just as he had done with table tennis. The immaculate artificial pitch funded by the town council did not yet exist. The kids played on a ‘red pitch’ as it is known here, a dirt pitch at the end of the complex that has now fallen into disuse. Sambou Tati was his first coach. Like his protégé he has come a long way. ‘I’ve been through practically everything at US Roissy. I started playing when I was thirteen, then I became a director, coach and I’ve been president for a few years now. I can’t even tell you how long it’s been, it’s gone so quickly,’ says the 48 year old, who looks a good ten years younger. ‘I was 30 when I coached Paul’s generation for the first time. I got to know him through his two brothers who were at the club and showed a lot of promise. I also had the opportunity to meet him at the social clubs because I was a youth worker. He was a kid like any other, except you could already see how gifted he was. When he played on the neighbourhood pitches, he scored goal after goal.’

Of course, the baby of the family had plenty of opportunity to follow in his brothers’ footsteps. The football stadium was very close to La Renardière. It took less than ten minutes to walk there past the cemetery, where the boules players gather, and out onto Rue Yitzhak Rabin, a stone’s throw from the sports complex.

Fassou Antoine had given his approval. The boys’ father took the activity very seriously, in fact. He did not wait for his youngest son to enrol at the club before putting him through his paces. Whenever the children came to visit, he would give them special sessions on a small dirt pitch near his apartment in Le Bois-Briard. He had them work on their technique and gave them plenty of tips. Over and over, he would tell the three brothers: ‘You have to learn to win whatever the circumstances.’ He told Paul to take the example set by his older brothers, to copy what they did and show the same will to win on the pitch. La Pioche listened to his father’s recommendations, which he intended to put into practice in September 1999 when he first played in a US Roissy shirt.

How did his first training session go? ‘He was impressive,’ remembers Sambou Tati, better known at the club by the nickname ‘Bijou’ (jewel or gem). ‘Paul likes to say that he scored two or three goals that day. To be frank, I don’t remember, and it’s difficult to say because at that age the goals are made from cones without a crossbar. It’s not easy to work out whether the ball has flown over the top or not. One thing for sure is that he had no fear. He wanted to dribble all the time, keep the ball and shoot from anywhere on the pitch. He was a bit selfish, but he was only six years old. It was just the beginning, the “source” as he likes to remember it.’