Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Luca Caioli

- Sprache: Englisch

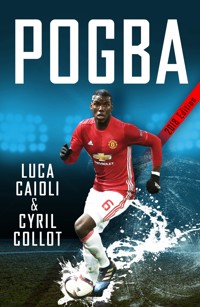

Paul Pogba, Kylian Mbappé and Antoine Griezmann were the stand-out stars of France's World Cup-winning team, drawing comparisons to the great class of '98. Be it Pogba's high-profile apprenticeships in the Premier League and Italy's Serie A, Griezmann's seizing his opportunity in Real Sociedad's youth academy or Mbappé's dazzling performances for AS Monaco in the UEFA Champions League, all three have forged their own distinct routes to the very top. The result is an unstoppable blend of pace, determination and creativity that cuts through opposition defences with devastating efficiency. Through exclusive testimonies from friends, families, managers and teammates, acclaimed football writers Luca Caioli and Cyril Collot document the trio's individual journeys and examine the phenomenal success of France's footballing superstars, including their success at the 2018 World Cup in Russia.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 194

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Introduction

The party belongs to those who write history. On the pitch of the Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow, Antoine Griezmann, drenched by the Russian downpour, shows the star off, smiling, pointing at his brand new jacket, fresh out of the packet. Next to him is Kylian Mbappé, the revelation, pointing at what he too had always dreamed of. There was no demonstration of excessive joy but a broad smile and an initial reaction on French television that speaks volumes about him as a person: ‘The road was long, but it’s been worth it. We’re world champions and we’re very proud. We wanted to make people happy and that’s why we’ve done all this.’

Paul Pogba’s mother, Yeo Moriba, is one of the first to hug her son. His brothers Florentin and Mathias join the party and the four have a family photo taken in La Pioche’s favourite pose.

In the dressing room, Benjamin Mendy – with his shirt off – and an overexcited Paul Pogba teach President of France Emmanuel Macron – drenched and missing his tie – to ‘Dab’. The scene would be immortalised on social media by Paul’s Instagram account. Other moments of glory punctuated the evening, such as Pogba wearing a Mexican sombrero, speaking perfect Spanish and even performing a tongue-in-cheek version of England’s ‘Football’s Coming Home’ anthem.

On 16 July, he strode across the tarmac at Roissy-Charles de Gaulle airport holding the World Cup. The new champions travelled by double-decker bus to the Élysée Palace, where Macron was waiting for them. After the President’s speech, it was time for the Pogba show to begin. Relieved of his tie, with the top button of his shirt undone and round sunglasses on his nose, Paul took the microphone and unleashed the master of ceremonies within him. He got the 3,000 people gathered at 55, Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré jumping, singing and dancing by chanting: ‘We beat them all!’, kidding around with Benjamin Mendy, leading a chorus of N’Golo Kanté’s name and asking the audience to do Grizou’s ‘Take the L’ dance. Paul Pogba in his purest state.

Pogba, Mbappé, Griezmann.

In other words: Paul, Kylian, Antoine.

Three musketeers for the second star. But how have they come so far?

Chapter 1

Mâcon, Roissy-en-Brie, Bondy

A small provincial town with just over 35,000 inhabitants, about 60 kilometres from Lyon, Mâcon is somewhere not necessarily used to attention. From a sporting perspective, there have not been many champions to speak of, or at least no one like Antoine Griezmann, who was born there in 21 March 1991.

Alain Griezmann, his father, had been a municipal employee for a number of years, so the family – Alain, Antoine, his mother Isabelle, his sister Maud and his younger brother Theo – lived in a small detached home next to the Les Gautriats community centre. It was a working-class neighbourhood, bordered by large pine trees and wide-open green spaces.

Georges Brassens Primary School, an imposing building surrounded by a huge tarmac playground with faint markings for a football pitch, is located in the middle of the neighbourhood, on Rue de Normandie. At school, as he himself admits, Antoine was always at the back of the class, usually chatting: ‘I was the kind of kid who would cut bits off my rubber to throw at my friends, and whenever my mother asked if I had any homework, funnily enough I never did!’

‘He was a simple, likeable kid who never caused any trouble,’ remembers his former headmaster, Marc Cornaton. ‘He was one of a group of boys and girls who played football at every break time. After school, it was football again.’ As he himself admits, Antoine had his routine at Les Gautriats, kicking the ball alone against the blue doors of the family garage, as well as playing in the basketball court below the house: ‘Even when we went to visit my parents’ friends I had to take my ball with me. Above all, football was fun, a real passion. When you’re ten years old, being a professional is just a dream, nothing more.’

‘God had not blessed my brother Fassou with children. He was living in France and was 50, so he returned home to sacrifice a ram in the hope of finding fertility.’ This is what Kébé, one of Fassou Antoine Pogba’s sisters, told journalist Alban Traquet in March 2017. ‘He then left again for Conakry in search of a romantic relationship.’

This trip marked the starting point for the meeting between the Christian, Fassou Antoine and the future mother of Paul Pogba, a Muslim woman in her twenties named Yeo Moriba. Like her future husband, she was from Forested Guinea. Despite the age difference, the ram sacrifice was not in vain. Yeo Moriba gave birth to two beautiful boys, Florentin and Mathias, on 19 August 1990. The small family would spend two years in the port city of Conakry before leaving the Guinean capital to settle permanently in France.

The couple and their two children took possession of an apartment in the Le Bois-Briard development in a peaceful area to the north-east of Roissy-en-Brie, about 30 kilometres to the south-east of Paris. Just one year later, on 15 March 1993, Paul Labile Pogba came into the world at the maternity unit in Lagny-sur-Marne hospital.

When he was only two years old, Paul’s parents decided to separate and Yeo Moriba moved a little further away to live in a modest uncluttered apartment in the neighbourhood known as La Renardière, where she brought up her three sons and two nieces on her own. ‘I made a lot of sacrifices. I worked morning and night to support them, so they wouldn’t be picked on by their schoolmates, would be happy and could go on holiday,’ she tells the journalists who come to interview her in her new well-to-do apartment in Bussy-Saint-Georges (about 30 kilometres from Roissy-en-Brie).

The boys were inseparable, and Paul was a real showman. He liked to dance, sing and play the clown. He soon christened himself ‘La Pioche’ (The Pickaxe). ‘There was an Ivorian actor in a TV series, Gohou Michel, who always said “La Pioche, il va piocher le village” [The Pickaxe, he’s going to use his pickaxe in the village], “Pogby La Pioche”. I liked it so even my mother started calling me “La Pioche”,’ Paul said in 2016. Next came the turn of his two brothers: Florentin, the craziest, would be ‘Le Zer’. Mathias, who ‘had a back like a gorilla’, would be simply ‘Le Dos’ (The Back). Le Zer, Le Dos and La Pioche soon carved out a reputation for themselves in the neighbourhood.

‘School?’ Paul’s mother is uncompromising for the TV cameras: ‘He was a total nightmare at school. He would tease his friends and the girls in his class because he was so high-spirited.’ Despite being a little embarrassed, Paul can only confirm: ‘It’s true, I was a real chatterbox. I couldn’t keep still. I had ants in my pants.’

Intelligent; lively; mischievous; a dreamer; nice; hyperactive; unruly; and difficult to manage: this is how some of his teachers describe Kylian Mbappé. He was a boy who couldn’t sit still at his desk to listen to his teacher’s explanations. ‘School was not his priority. Kylian had one idea in his head and that was becoming a professional footballer,’ says Jean-François ‘Fanfan’ Suner, AS Bondy technical director and one of Kylian’s first coaches.

Born on 20 December 1998 and christened with the name Kylian Sanmi (short for Adesanmi, ‘the crown fits me’ in Yoruba), he was the first child of Fayza Lottin and Wilfrid Mbappé, who lived on the second floor of a white building at number 4, Allée des Lilas, a five-storey 1950s council building in the centre of Bondy. Fayza – 24 years old at the time and originally from Algeria – grew up in Bondy Nord, in the Terre Saint Blaise neighbourhood. She played handball on the right wing for AS Bondy in Division 1 in the late 1990s and used to work as an instructor in the Maurice Petitjean and Blanqui neighbourhoods. Wilfrid, also an instructor, was 30 when he met Fayza; he was born in Douala in Cameroon and had come to France in search of a better life. First Bobigny, then Bondy, a suburb to the northeast of Paris, nine kilometres from the city’s Porte de Pantin, where he worked and played football for years.

‘He was a good player, a number 10 who was fond of keeping the ball,’ according to Fanfan. ‘When he stopped playing, he came back to us and we offered him a coaching position.’ One player in particular attracted his attention: he was eleven years old and had arrived from Kinshasa. The boy was called Jirès Kembo-Ekoko; he was the son of Jean Kembo, a midfielder for the Zaire team that become the first team from sub-Saharan Africa to qualify for the World Cup in 1974. Wilfrid was Jirès first coach in 1999 and soon also became his legal guardian; the Lamari-Mbappé Lottin family did not adopt him but Jirès went to live with them and soon became Kylian’s big brother, role model, idol and first footballing hero.

Chapter 2

Kicking a ball for the first time

‘As soon as he started walking he had a ball at his feet. He spent his free time doing keepie uppies,’ remembers Christophe Grosjean, a friend of the Griezmann family and one of his first coaches. For Antoine it was all about playing. ‘He was only interested in waiting for break time so he could go outside and play football,’ remembers his childhood friend, Jean-Baptiste Michaud.

His pitches were all over the town, at the foot of the tower blocks at La Chanaye, near his grandmother’s house: ‘People in this part of town remember Antoine as a little blond kid who wore French national team shorts,’ recalls André de Sousa, another childhood mate. ‘When we were three or four, his parents would take him to visit his grandmother, who lived on the floor below us, and we would take the opportunity to have a kick about. Well, I say “take the opportunity”; he would force me to play with him!’

For the start of the 1997–98 season, Antoine officially received his first French Football Federation licence at the Entente Charnay-Mâcon 71, later Union du Football Mâconnais (UFM). ‘We started him at five and a half’, confirms his first coach Bruno Chetoux. His father trained a team at the club and Antoine was always hanging around the pitches. To start with, we would only let him train because he was still too young to take part in Saturday matches. But eventually we had him play a few matches before he turned six.’ Unsurprisingly, Antoine took to it like a duck to water and attended every session without fail.

‘We could see straight away that he was a good player,’ explains Chetoux. ‘But the most surprising thing was that at that age gifted children tend to be more selfish with their play. Not him, he liked to score goals, but he was also happy to help others score.’

Antoine soon joined the group born a year earlier, in 1990, quickly found his feet and showed himself to have the mindset of a true champion: ‘We didn’t lose many matches, hardly ever. When it did happen, it was a big deal. I remember an indoor tournament that we lost on penalties. Antoine missed his last attempt. He left in tears, without even waiting for the prize-giving. That showed me his temperament.’

It was always the same. Yeo Moriba had to raise her voice: ‘Hey, boys! It’s time to come in! Hurry up,’ she shouted from her window on the twelfth floor of the tall white tower, using her deep, strident voice to make herself heard. Florentin, Mathias and Paul eventually finished their match, picked up their ball and ran up alleyway no. 13 at the Résidence La Renardière.

Paul was seven years old; Mathias and Florentin were ten. The City Stade had just been built at the end of the playground, along the railway track. It quickly became a rallying point for all the local kids. No prisoners were taken in this rough street football; the boys played right up against the walls and would even hit each other during one-on-ones. Paul was often knocked to the ground. Whenever a tear began to appear in the corner of his eye, he was immediately called to order: ‘Stop crying and play!’ his brothers commanded. As the matches went on, he became stronger and made progress.

The kid had character alright, as well as a marked taste for competition, something it was said he got from Fassou Antoine. The boys’ father took the activity very seriously and whenever the children came to visit, he would give them special sessions on a small dirt pitch near his apartment in Le Bois-Briard.

Paul joined US Roissy in September 1999, following in the footsteps of his two brothers. Sambou Tati, his first coach, remembers: ‘I was 30 when I coached Paul’s generation for the first time … He was a kid like any other, except you could already see how gifted he was. When he played on the neighbourhood pitches, he scored goal after goal.’

How did his first training session go? ‘He was impressive,’ comments Sambou Tati. ‘Paul likes to say that he scored two or three goals that day. To be frank, I don’t remember, and it’s difficult to say because at that age the goals are made from cones without a crossbar … One thing for sure is that he had no fear. He wanted to dribble all the time, keep the ball and shoot from anywhere on the pitch. He was a bit selfish, but he was only six years old.’

‘He was here every day, always with his father, who was the technical director for the categories from U11 to U17. Kylian must have been three or four years old,’ remembers Athmane Airouche, the president of AS Bondy since June 2017. ‘He was the club’s little mascot. You would see him come into the dressing room holding a ball and sit in the corner, in silence, to hear what the manager had to say before the game. And because Kylian has always been a sponge … from an early age he assimilated football concepts that others only heard and understood years later.’

At aged six, Kylian would finally be allowed to enrol at AS Bondy. His first coach was his dad, a man Airouche would describe as: ‘Generous, a hard-worker and fair. Like Fayza, his wife. I can only think of them together because they’re like two halves of a whole.’ Antonio Riccardi, who has been at AS Bondy for twelve years, first as a player, now as head of the U15s, adds: ‘I remember Kylian at four years old, singing the ‘Marseillaise’ with his hand on his heart or when, at six or seven, he would tell you not to worry and that someday he would be playing for the national team in the World Cup. All you could do was smile, when he was seriously planning out his future: Clairefontaine, the France team, Madrid. We just thought he was a dreamer,’ claims Riccardi.

‘His idol was Cristiano Ronaldo. He wallpapered his room with posters of the Portuguese player. He liked his dribbling and would watch him on television and try to repeat it on the pitch.’ But the five-time Ballon d’Or winner was not the only star Kylian admired. There was also Ronaldinho and Zidane. His childhood friends still make fun of him for the time he showed up at the hairdressers and asked, in all seriousness, for the same style as Zizou. Years later, Kylian would try to justify it: ‘When you like a player, you want to do everything just like them. Back then, I didn’t know it was baldness!’

Chapter 3

Child’s play

Antoine was quickly moved up a category and joined the U13 group trained by Christophe Grosjean for the 2000–01 season. ‘That first year, he didn’t really manage to hold his own because physique counts for a lot, and at that age he wasn’t ready in that respect. But by the second year, he had begun to get bigger physically and better technically. We were still playing in teams of nine and I liked to put him on one side in the centre left position.’

At that time, Antoine spent almost every waking moment with his two best friends, Stéphane Rivera and Jean-Baptiste Michaud. They had no trouble rounding up local kids to make up teams for breakneck matches: ‘We imagined we were playing in the World Cup or the Champions League … When we scored, we would try to celebrate our goals in the most original way possible. It was 2002, so Antoine was fond of sliding like Thierry Henry or Fernando Torres,’ recalls Jean-Baptiste Michaud.

Despite being vertically challenged, Antoine was one of the most promising players in the Saône-et-Loire département in his age category. Paul Guérin, who has been the FFF’s Regional Technical Adviser for Burgundy since 2000, had been following the boy from Mâcon closely for several years. ‘He was an engaging kid and everyone liked him. He was also incredibly passionate.’

‘At twelve and thirteen he distinguished himself every year in the Foot Challenge,’ continues Guérin. This competition involved a series of keepie uppies and technical challenges. Antoine was a finalist in 2003, his first year, and won it the following year. In 25 years, only two other players from Burgundy had equalled this and both attended the prestigious Olympique Lyonnais training academy. But Antoine would never have the opportunity to wear the shirt of his favourite club.

From the U10s onwards, Paul was clearly a cut above his teammates. ‘We had a fantastic generation,’ remembers Papis Magassa, one of his coaches. ‘Paul was the individual player who often tipped the match in our direction.’ The problem was that his attitude at school was not to Fassou Antoine’s liking. ‘Sometimes, he didn’t turn up at training so we would call his mum to make sure he was okay. In the end it would turn out that his father had punished him. He was tough but fair with him. Paul could cry for hours, but he would never go back on his decision.’

The 2005–06 season, his seventh at the club, was looming. In the U13 category, Paul was reunited with his first coach, Sambou Tati: ‘I put him in as playmaker. I spent my time telling him to play more simply and to stop showboating, but he didn’t listen to me. So once I gave him an ear bashing at half-time: “Paul, you’re not Ronaldinho, you’re crap, you’re not the star in this team, you’re bringing nothing.” He started crying, but as soon as the second half kicked off, he massacred everyone.’

US Roissy finished third in its league and Paul even made several appearances for the U15s. Scouts from professional clubs began hanging around the pitches but Fassou Antoine was not ready to hear talk of leaving Roissy just yet. ‘After such a good season, he couldn’t stay with us, so I advised him to join US Torcy,’ says Tati. Stéphane Albe, the coach at Torcy, a neighbouring town of just over 20,000 inhabitants, was not surprised by the call. ‘Our clubs had always had a good relationship and we knew about Paul’s potential.’

For his first year in eleven-a-side football, Paul went straight into the midfield. Usually as a defensive midfielder, but also as a box-to-box midfielder or a number 10: ‘It’s true that he liked to go a long way out of his position,’ confirms Stéphane Albe. ‘He already had his own way of coming forward, of breaking through. He was capable of taking out several players with a sidestep and of making an impressive difference … How many goals did he score like that with us? By picking up the ball before speeding up, getting support from another player and then scoring? It must have been at least a dozen.’

US Torcy gave a good account of themselves in the U14 league. The yellow and reds strung together some good performances and finished ‘second or third in the table’, according to Albe. ‘Paul brought a lot to the team, through his play, of course, but also through his charisma and mindset … He was really popular with his teammates and was a delight to coach.’

What about Kylian Mbappé? ‘He was a child like all the others who dreamt of becoming footballers, only he had qualities the others didn’t,’ says Athmane Airouche. Fanfan goes on to explain: ‘I had him for a year when he was playing above his age category in the U10s. At training, you could see right away that he had a technical ease. We knew he would go right to the top if there weren’t any physical glitches.’

‘He made the difference,’ adds Antonio Riccardi. ‘Quickly, very quickly, like he was a senior playing at a high level, he understood how to shake off his marker, how to get free for his teammates. What was his best quality? His pace with the ball at his feet.’

‘He was capable of scoring 50 goals a season in the U13s’, remembers Théo Suner, who played with Kylian in almost every category at AS Bondy. ‘We didn’t even count the goals. He could score three in one game and provide two assists. Kylian was a good friend, he was fun and always smiling.’ And Fanfan adds another memory, perhaps one of the best about the lively little kid in a green and white shirt with the number 10 on his back. ‘We were playing an important game against Bobigny. It was 0–0 at half-time and we were all over the place. I spoke to the players and told them: “Listen, we’re not going to get worked up today. It’s simple, in the second half, we’re just going to give the ball to Kylian. That’s it.” We won 4–0 and he was the one who scored the goals.’

Chapter 4