Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

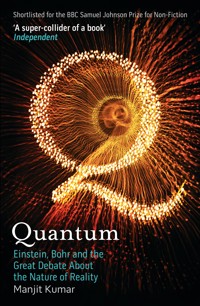

'This is about gob-smacking science at the far end of reason ... Take it nice and easy and savour the experience of your mind being blown without recourse to hallucinogens' Nicholas Lezard, Guardian For most people, quantum theory is a byword for mysterious, impenetrable science. And yet for many years it was equally baffling for scientists themselves. In this magisterial book, Manjit Kumar gives a dramatic and superbly-written history of this fundamental scientific revolution, and the divisive debate at its core. Quantum theory looks at the very building blocks of our world, the particles and processes without which it could not exist. Yet for 60 years most physicists believed that quantum theory denied the very existence of reality itself. In this tour de force of science history, Manjit Kumar shows how the golden age of physics ignited the greatest intellectual debate of the twentieth century. Quantum theory is weird. In 1905, Albert Einstein suggested that light was a particle, not a wave, defying a century of experiments. Werner Heisenberg's uncertainty principle and Erwin Schrodinger's famous dead-and-alive cat are similarly strange. As Niels Bohr said, if you weren't shocked by quantum theory, you didn't really understand it. While "Quantum" sets the science in the context of the great upheavals of the modern age, Kumar's centrepiece is the conflict between Einstein and Bohr over the nature of reality and the soul of science. 'Bohr brainwashed a whole generation of physicists into believing that the problem had been solved', lamented the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Murray Gell-Mann. But in "Quantum", Kumar brings Einstein back to the centre of the quantum debate. "Quantum" is the essential read for anyone fascinated by this complex and thrilling story and by the band of brilliant men at its heart.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 802

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Quantum

‘An exhaustive and brilliant account of decades of emotionally charged discovery and argument, friendship and rivalry spanning two world wars. The explanations of science and philosophical interpretation are pitched with an ideal clarity for the general reader [and] perhaps most interestingly, although the author is admirably even-handed, it is difficult not to think of Quantum, by the end, as a resounding rehabilitation of Albert Einstein.’ Steven Poole, Guardian

‘The reason this book is, in fact, so readable is because it contains vivid portraits of the scientists involved, and their contexts … This is about gob-smacking science at the far end of reason … Take it nice and easy and savour the experience of your mind being blown without recourse to hallucinogens.’ Nicholas Lezard, Paperback Choice of the Week, Guardian

‘Kumar is an accomplished writer who knows how to separate the excitement of the chase from the sometimes impenetrable mathematics. In Quantum he tells the story of the conflict between two of the most powerful intellects of their day: the hugely famous Einstein and the less well-known but just as brilliant Dane, Niels Bohr.’ Financial Times

‘Manjit Kumar’s Quantum is a super-collider of a book, shaking together an exotic cocktail of free-thinking physicists, tracing their chaotic interactions and seeing what God-particles and black holes fly up out of the maelstrom. He provides probably the most lucid and detailed intellectual history ever written of a body of theory that makes other scientific revolutions look limp-wristed by comparison.’ Independent

‘Quantum by Manjit Kumar is so well written that I now feel I’ve more or less got particle physics sussed. Quantum transcends genre – it is historical, scientific, biographical, philosophical.’ Readers’ Books of the Year, Guardian

‘Highly readable … A welcome addition to the popular history of twentieth-century physics.’ Nature

‘An elegantly written and accessible guide to quantum physics, in which Kumar structures the narrative history around the clash between Einstein and Bohr, and the anxiety that quantum theory “disproved the existence of reality”.’ Scotland on Sunday

‘It would be a rare author who could fully address both the philosophical and the historical issues – an even rarer one who could make it all palatable and entertaining to a general audience. If Kumar scores less than full marks it is only because of the admirably ambitious scale of his book.’ Andrew Crumey, Daily Telegraph

‘Quantum: Einstein, Bohr and the Great Debate about the Nature of Reality by Manjit Kumar is one of the best guides yet to the central conundrums of modern physics.’ John Banville, Books of the Year, The Age, Australia

‘By combining personalities and physics – both of an intriguingly quirky nature – Kumar transforms the sub-atomic debate between Einstein, Niels Bohr and others in their respective circles into an absorbing and … comprehensible narrative.’ Independent

‘In this magisterial study of the issue, Manjit Kumar probes beyond the froth and arcane arguments and reveals what really lies behind the theory and ultimately what it means for the development of science … Here we have an erudite work that takes the debate into new territory.’ Good Book Guide

‘Quantum is a fascinating, powerful and brilliantly written book that shows one of the most important theories of modern science in the making and discusses its implications for our ideas about the fundamental nature of the world and human knowledge, while presenting intimate and insightful portraits of people who made the science. Highly recommended.’ thebookbag.co.uk

‘This is the biography of an idea and as such reads much like a thriller.’ Ham & High

‘It is a revolution that, even if most people don’t fully realise yet, has changed the face of science – and of our understanding of the nature of reality – forever. Beautifully written in a tour de force that covers the fierce debate about the foundations of reality that gripped the scientific community through the 20th century, this book also looks at the personal collision of thinking and belief between two of quantum theory’s great men, Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr … This is the world of Alice down the cosmic rabbit hole. Take a peek.’ Odyssey, South Africa

‘Kumar brings us through the detail of the various advances, confusions and mistakes, and what emerges clearly is a picture of how science works as a great international collective effort.’ Irish Times

‘A dramatic, powerful and superbly written history.’ Publishing News

‘The most important popular science book published this year.’ Bookseller

‘Rich and intensively researched … this qualitative, narrative method is a great way to get your head around the most extraordinary and intellectually demanding theory ever devised. Kumar brings to life the wide spectrum of personalities involved in the development of the quantum theory, from the quiet and thoughtful Bohr, to the lively womanising Schrödinger … I had difficulty putting this book down.’ Astronomy Now

‘As an introduction to a fiendishly difficult branch of science it is hard to improve upon Quantum. This is one of the finest accounts of the 20th century’s greatest intellectual adventure.’ Express Buzz, India

‘If theoretical and often boring physics can be delivered in an exciting novel style, Manjit Kumar has done it. His Quantum is an engrossing account of the high caliber intellectual and academic debates, sometimes acrimonious, on the then evolving concept of Quantum, in the 20th century.’ The Organiser, India

‘Manjit Kumar writes a pulsating narrative about the history of modern science’s most fundamental revolution in Quantum … [He] brings lucidity and a sense of drama to what is usually considered by lay readers as an esoteric, bubble-chambered subject. He does this without sacrificing the ‘science of it’ at the altar of readability. The triumphs and the tribulations, the politics and the physics, the humanity and the genius of the protagonists all collide to produce the sort of energy that we usually expect in a Le Carré thriller.’ Hindustan Times, India

‘A staggering account of the scientific revolution that still challenges our notions of reality. Kumar provides a gripping narrative of the birth of atomic physics in the first half of the 20th century … [He] evokes the passion and excitement of the period and writes with sparkling clarity and wit.’ Kirkus Reviews

‘Other narratives may rival in their sweeping scopes, scenic settings, and cast of characters, but no other area of science has raised deeper questions about the very nature of reality. In Quantum, Manjit Kumar breathes new life into this classic story through superb writing and careful research, focusing on a philosophical conflict between Niels Bohr and Albert Einstein that still resonates through physics to this day.’ Seed Magazine, USA

‘A lucid account of quantum theory (and why you should care) combined with a gripping narrative.’ San Francisco Chronicle

‘Kumar has done a splendid job of explaining complex theories and describing the people involved with discovering them, mired in cultural and historical upheavals that haunted all of them. This is a necessary, mesmerizing, and meticulous volume.’ Providence Journal, USA

Quantum

Quantum

Einstein, Bohr and the Great Debate About the Nature of Reality

Manjit Kumar

This edition published in the UK in 2014 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Previously published in paperback in 2009 by Icon Books Ltd

Originally published in the UK in 2008 by Icon Books Ltd

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by

Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

ISBN: 978-184831-035-3

Text copyright © 2009 Manjit Kumar

The author has asserted his moral rights.

Line drawings by Nicholas Halliday

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in Minion by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

ForLahmber Ram and Gurmit Kaur Pandora, Ravinder, and Jasvinder

CONTENTS

List of illustrations

Prologue

PART I: THE QUANTUM

Chapter 1The Reluctant Revolutionary

Chapter 2The Patent Slave

Chapter 3The Golden Dane

Chapter 4The Quantum Atom

Chapter 5When Einstein Met Bohr

Chapter 6The Prince of Duality

PART II: BOY PHYSICS

Chapter 7Spin Doctors

Chapter 8The Quantum Magician

Chapter 9‘A Late Erotic Outburst’

Chapter 10Uncertainty in Copenhagen

PART III: TITANS CLASH OVER REALITY

Chapter 11Solvay 1927

Chapter 12Einstein Forgets Relativity

Chapter 13Quantum Reality

PART IV: DOES GOD PLAY DICE?

Chapter 14For Whom Bell’s Theorem Tolls

Chapter 15The Quantum Demon

Timeline

Glossary

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

IMAGES IN THE TEXT

Figure 1

The characteristics of a wave

Figure 2

Distribution of blackbody radiation showing Wien’s displacement law

Figure 3

The photoelectric effect

Figure 4

Young’s two-slits experiment

Figure 5

The periodic table

Figure 6

Some of the stationary states and corresponding energy levels of the hydrogen atom

Figure 7

Energy levels, line spectra and quantum jumps

Figure 8

Electron orbits for n=3 and k=1, 2, 3 in the Bohr-Sommerfeld model of the hydrogen atom

Figure 9

Standing waves of a string tethered at both ends

Figure 10

Standing electron waves in the quantum atom

Figure 11

A wave packet formed from the superposition of a group of waves

Figure 12

Determining the position of a wave but not the wavelength; measuring the wavelength but not the position

Figure 13

Einstein’s single-slit thought experiment

Figure 14

Bohr’s rendition of Einstein’s single-slit thought experiment

Figure 15

Einstein’s two-slits thought experiment

Figure 16

Bohr’s design of a moveable first screen

Figure 17

Two-slit experiment with both slits open and with one slit closed

Figure 18

Bohr’s rendition of Einstein’s 1930s light box

PLATE SECTION

i.

The fifth Solvay conference, 1927

ii.

Max Planck

iii.

Ludwig Boltzmann

iv.

‘The Olympia Academy’

v.

Albert Einstein in 1912

vi.

The first Solvay conference, 1911

vii.

Niels Bohr

viii.

Ernest Rutherford

ix.

The Bohr Institute

x.

Bohr and Einstein in Brussels, 1930

xi.

Bohr and Einstein at Paul Ehrenfest’s house

xii.

Louis de Broglie

xiii.

Wolfgang Pauli

xiv.

Max Born, Niels Bohr and others

xv.

Oskar Klein, George Uhlenbeck and Samuel Goudsmit

xvi.

Werner Heisenberg

xvii.

Bohr, Heisenberg and Pauli

xviii.

Paul Dirac

xix.

Erwin Schrödinger

xx.

Dirac, Heisenberg, Schrödinger in Stockholm

xxi.

Albert Einstein at home in 1954

xxii.

Bohr’s last blackboard diagram

xxiii.

David Bohm

xxiv.

John Stewart Bell

About the author

Manjit Kumar has degrees in physics and philosophy. He was the founding editor of Prometheus, an interdisciplinary journal that covered the arts and sciences, described by one reviewer as ‘perhaps the finest magazine that I’ve ever read’. He is the co-author of Science and the Retreat from Reason, which introduced key areas of modern science while defending the Enlightenment notions of social progress and scientific advance against the loss of faith in progress and science. Published in 1995, it was critically acclaimed as a ‘corrective to the hype’, ‘thought-provoking’, and ‘undoubtedly one of the best introductions one can find to the crisis of confidence within science itself’. His second book, Quantum, was shortlisted for the BBC Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction in 2009 and has been translated into more than a dozen languages. He has written and reviewed for numerous publications including the Guardian, Independent, Times, Daily Telegraph, Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, Literary Review and New Scientist, and was Consulting Science Editor at Wired. He lives in north London with his wife and two sons.

www.manjitkumar.com

Prologue

THE MEETING OF MINDS

Paul Ehrenfest was in tears. He had made his decision. Soon he would attend the week-long gathering where many of those responsible for the quantum revolution would try to understand the meaning of what they had wrought. There he would have to tell his old friend Albert Einstein that he had chosen to side with Niels Bohr. Ehrenfest, the 34-year-old Austrian professor of theoretical physics at Leiden University in Holland, was convinced that the atomic realm was as strange and ethereal as Bohr argued.1

In a note to Einstein as they sat around the conference table, Ehrenfest scribbled: ‘Don’t laugh! There is a special section in purgatory for professors of quantum theory, where they will be obliged to listen to lectures on classical physics ten hours every day.’2 ‘I laugh only at their naiveté,’ Einstein replied.3 ‘Who knows who would have the [last] laugh in a few years?’ For him it was no laughing matter, for at stake was the very nature of reality and the soul of physics.

The photograph of those gathered at the fifth Solvay conference on ‘Electrons and Photons’, held in Brussels from 24 to 29 October 1927, encapsulates the story of the most dramatic period in the history of physics. With seventeen of the 29 invited eventually earning a Nobel Prize, the conference was one of the most spectacular meetings of minds ever held.4 It marked the end of a golden age of physics, an era of scientific creativity unparalleled since the scientific revolution in the seventeenth century led by Galileo and Newton.

Paul Ehrenfest is standing, slightly hunched forward, in the back row, third from the left. There are nine seated in the front row. Eight men and one woman; six have Nobel Prizes in either physics or chemistry. The woman has two, one for physics awarded in 1903 and another for chemistry in 1911. Her name: Marie Curie. In the centre, the place of honour, sits another Nobel laureate, the most celebrated scientist since the age of Newton: Albert Einstein. Looking straight ahead, gripping the chair with his right hand, he seems ill at ease. Is it the winged collar and tie that are causing him discomfort, or what he has heard during the preceding week? At the end of the second row, on the right, is Niels Bohr, looking relaxed with a half-whimsical smile. It had been a good conference for him. Nevertheless, Bohr would be returning to Denmark disappointed that he had failed to convince Einstein to adopt his ‘Copenhagen interpretation’ of what quantum mechanics revealed about the nature of reality.

Instead of yielding, Einstein had spent the week attempting to show that quantum mechanics was inconsistent, that Bohr’s Copenhagen interpretation was flawed. Einstein said years later that ‘this theory reminds me a little of the system of delusions of an exceedingly intelligent paranoic, concocted of incoherent elements of thoughts’.5

It was Max Planck, sitting on Marie Curie’s right, holding his hat and cigar, who discovered the quantum. In 1900 he was forced to accept that the energy of light and all other forms of electromagnetic radiation could only be emitted or absorbed by matter in bits, bundled up in various sizes. ‘Quantum’ was the name Planck gave to an individual packet of energy, with ‘quanta’ being the plural. The quantum of energy was a radical break with the long-established idea that energy was emitted or absorbed continuously, like water flowing from a tap. In the everyday world of the macroscopic where the physics of Newton ruled supreme, water could drip from a tap, but energy was not exchanged in droplets of varying size. However, the atomic and subatomic level of reality was the domain of the quantum.

In time it was discovered that the energy of an electron inside an atom was ‘quantised’; it could possess only certain amounts of energy and not others. The same was true of other physical properties, as the microscopic realm was found to be lumpy and discontinuous and not some shrunken version of the large-scale world that humans inhabit, where physical properties vary smoothly and continuously, where going from A to C means passing through B. Quantum physics, however, revealed that an electron in an atom can be in one place, and then, as if by magic, reappear in another without ever being anywhere in between, by emitting or absorbing a quantum of energy. This was a phenomenon beyond the ken of classical, non-quantum physics. It was as bizarre as an object mysteriously disappearing in London and an instant later suddenly reappearing in Paris, New York or Moscow.

By the early 1920s it had long been apparent that the advance of quantum physics on an ad hoc, piecemeal basis had left it without solid foundations or a logical structure. Out of this state of confusion and crisis emerged a bold new theory known as quantum mechanics. The picture of the atom as a tiny solar system with electrons orbiting a nucleus, still taught in schools today, was abandoned and replaced with an atom that was impossible to visualise. Then, in 1927, Werner Heisenberg made a discovery that was so at odds with common sense that even he, the German wunderkind of quantum mechanics, initially struggled to grasp its significance. The uncertainty principle said that if you want to know the exact velocity of a particle, then you cannot know its exact location, and vice versa.

No one knew how to interpret the equations of quantum mechanics, what the theory was saying about the nature of reality at the quantum level. Questions about cause and effect, or whether the moon exists when no one is looking at it, had been the preserve of philosophers since the time of Plato and Aristotle, but after the emergence of quantum mechanics they were being discussed by the twentieth century’s greatest physicists.

With all the basic components of quantum physics in place, the fifth Solvay conference opened a new chapter in the story of the quantum. For the debate that the conference sparked between Einstein and Bohr raised issues that continue to preoccupy many eminent physicists and philosophers to this day: what is the nature of reality, and what kind of description of reality should be regarded as meaningful? ‘No more profound intellectual debate has ever been conducted’, claimed the scientist and novelist C.P. Snow. ‘It is a pity that the debate, because of its nature, can’t be common currency.’6

Of the two main protagonists, Einstein is a twentieth-century icon. He was once asked to stage his own three-week show at the London Palladium. Women fainted in his presence. Young girls mobbed him in Geneva. Today this sort of adulation is reserved for pop singers and movie stars. But in the aftermath of the First World War, Einstein became the first superstar of science when in 1919 the bending of light predicted by his theory of general relativity was confirmed. Little had changed when in January 1931, during a lecture tour of America, Einstein attended the premiere of Charlie Chaplin’s movie City Lights in Los Angeles. A large crowd cheered wildly when they saw Chaplin and Einstein. ‘They cheer me because they all understand me,’ Chaplin told Einstein, ‘and they cheer you because no one understands you.’7

Whereas the name Einstein is a byword for scientific genius, Niels Bohr was, and remains, less well known. Yet to his contemporaries he was every inch the scientific giant. In 1923 Max Born, who played a pivotal part in the development of quantum mechanics, wrote that Bohr’s ‘influence on theoretical and experimental research of our time is greater than that of any other physicist’.8 Forty years later, in 1963, Werner Heisenberg maintained that ‘Bohr’s influence on the physics and the physicists of our century was stronger than that of anyone else, even than that of Albert Einstein’.9

When Einstein and Bohr first met in Berlin in 1920, each found an intellectual sparring partner who would, without bitterness or rancour, push and prod the other into refining and sharpening his thinking about the quantum. It is through them and some of those gathered at Solvay 1927 that we capture the pioneering years of quantum physics. ‘It was a heroic time’, recalled the American physicist Robert Oppenheimer, who was a student in the 1920s.10 ‘It was a period of patient work in the laboratory, of crucial experiments and daring action, of many false starts and many untenable conjectures. It was a time of earnest correspondence and hurried conferences, of debate, criticism and brilliant mathematical improvisation. For those who participated it was a time of creation.’ But for Oppenheimer, the father of the atom bomb: ‘There was terror as well as exaltation in their new insight.’

Without the quantum, the world we live in would be very different. Yet for most of the twentieth century, physicists accepted that quantum mechanics denied the existence of a reality beyond what was measured in their experiments. It was a state of affairs that led the American Nobel Prize-winning physicist Murray Gell-Mann to describe quantum mechanics as ‘that mysterious, confusing discipline which none of us really understands but which we know how to use’.11 And use it we have. Quantum mechanics drives and shapes the modern world by making possible everything from computers to washing machines, from mobile phones to nuclear weapons.

The story of the quantum begins at the end of the nineteenth century when, despite the recent discoveries of the electron, X-rays, and radioactivity, and the ongoing dispute about whether or not atoms existed, many physicists were confident that nothing major was left to uncover. ‘The more important fundamental laws and facts of physical science have all been discovered, and these are now so firmly established that the possibility of their ever being supplanted in consequence of new discoveries is exceedingly remote’, said the American physicist Albert Michelson in 1899. ‘Our future discoveries,’ he argued, ‘must be looked for in the sixth place of decimals.’12 Many shared Michelson’s view of a physics of decimal places, believing that any unsolved problems represented little challenge to established physics and would sooner or later yield to time-honoured theories and principles.

James Clerk Maxwell, the nineteenth century’s greatest theoretical physicist, had warned as early as 1871 against such complacency: ‘This characteristic of modern experiments – that they consist principally of measurements – is so prominent, that the opinion seems to have got abroad that in a few years all the great physical constants will have been approximately estimated, and that the only occupation which will be left to men of science will be to carry on these measurements to another place of decimals.’13 Maxwell pointed out that the real reward for the ‘labour of careful measurement’ was not greater accuracy but the ‘discovery of new fields of research’ and ‘the development of new scientific ideas’.14 The discovery of the quantum was the result of just such a ‘labour of careful measurement’.

In the 1890s some of Germany’s leading physicists were obsessively pursuing a problem that had long vexed them: what was the relationship between the temperature, the range of colours, and the intensity of light emitted by a hot iron poker? It seemed a trivial problem compared to the mystery of X-rays and radioactivity that had physicists rushing to their laboratories and reaching for their notebooks. But for a nation forged only in 1871, the quest for the solution to the hot iron poker, or what became known as ‘the blackbody problem’, was intimately bound up with the need to give the German lighting industry a competitive edge against its British and American competitors. But try as they might, Germany’s finest physicists could not solve it. In 1896 they thought they had, only to find within a few short years that new experimental data proved that they had not. It was Max Planck who solved the blackbody problem, at a cost. The price was the quantum.

PART I

THE QUANTUM

‘Briefly summarized, what I did can be described as simply an act of desperation.’

—MAX PLANCK

‘It was as if the ground had been pulled out from under one, with no firm foundation to be seen anywhere, upon which one could have built.’

—ALBERT EINSTEIN

‘For those who are not shocked when they first come across quantum theory cannot possibly have understood it.’

—NIELS BOHR