Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

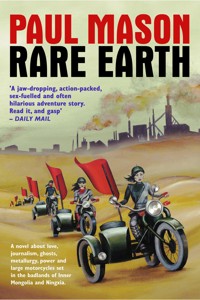

A washed up TV reporter stumbles onto a corruption scandal in Western China. Pursued through the desert by a psychotic spin-doctor and a world-weary cop, he discovers the real China: illegal metal mines, a fashion-crazed gang of girl bikers, a whole commune of Tiananmen Square survivors and the up-market sleaze-joints of Beijing. En route, he clashes with a stellar cast of people-traffickers, prostitutes and TV execs. But then the unquiet dead begin to intervene: ghosts from his own past and the past of Chinese Communism; the 'spirits that hover three feet above our heads' of Chinese folklore. Rare Earth is a story about love, journalism, ghosts, metallurgy, vintage militaria and large motorcycles set in the badlands of Inner Mongolia and Ningxia. It is about the west's inability to understand the East; one man's epic journey across a dying landscape, where 'thousands of pairs of eyes peer beyond grimy windowpanes into the moonless sky, looking for something better.'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 386

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

RARE EARTH

A washed up TV reporter stumbles onto a corruption scandal in Western China. Pursued through the desert by a psychotic spin-doctor and a world-weary cop, he discovers the real China: illegal metal mines, a fashion-crazed gang of girl bikers, a whole commune of Tiananmen Square survivors and the up-market sleaze-joints of Beijing.

En route, he clashes with a stellar cast of people-traffickers, prostitutes and TV execs. But then the unquiet dead begin to intervene: ghosts from his own past and the past of Chinese Communism; the ‘spirits that hover three feet above our heads’ of Chinese folklore.

Rare Earth is a story about love, journalism, ghosts, metallurgy, vintage militaria and large motorcycles set in the badlands of Inner Mongolia and Ningxia. It is about the west’s inability to understand the East; one man’s epic journey across a dying landscape, where ‘thousands of pairs of eyes peer beyond grimy windowpanes into the moonless sky, looking for something better.’

About the Author

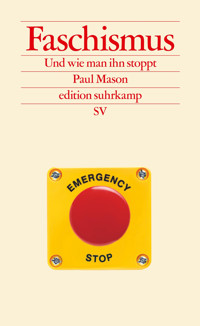

Paul Mason is the award winning economics editor of the BBC current affairs show Newsnight and author of Meltdown: The End of the Age of Greed, an account of the 2008 financial crisis. Why it is Kicking off Everywhere: The New Global Revolutions was published in 2012. This is his first novel.

RARE EARTH

Paul Mason

“All that, the Spring bore towards me, And the flower I plucked, Father’s spirit I thought it was, Dancing and moaning.”Spring, Aasmund Olavsson Vinje

Contents

RARE EARTHAbout the AuthorTitle PageDedicationPART ONE12345678PART TWO12345678PART THREE12345678910PART FOUR123456789PART FIVE12345678910111213PART SIX1234567891011121314CUTTINGSCopyright

PART ONE

“Governing a large country is like frying a small fish. You spoil it with too much poking.”

Lao Tzu

1

It was morning but his body was telling him midnight. That’s why he was trying to siphon the Jack Daniels into the can of Coke. It was only the rattle of the van making his fingers shake. The task complete, Brough held the can up into the flickering sunlight to toast the dawn.

Flashing by to the west were the mountains, same as yesterday: a vertical rock face without snow or vegetation, emitting silence into the landscape. The low sun was making bits of rubble cast long points of shadow across the earth, which was the colour of cigarette ash.

“Helan Shan mountain range famous for excellent feng-shui!”

Chun-li’s voice startled him. She’d been asleep the moment before, like everybody else except the driver. Brough squinted at her through the makeup mirror: sharp fringe, long hair, face hidden behind a pair of plastic sunglasses.

“Feng-shui dictates ideal position for burial is with back to mountains, feet to river,” she chirped.

They’d crossed the Yellow River an hour ago: a bleak stretch of churning water. Now they were heading north along a pristine but deserted road, with fields on one side and this rock-strewn desolation on the other.

“Notice small cairns?”

He’d spotted them: little grey piles of rock dotted across the plain.

“Many important Chinese businessmen buried here.”

“What,” Brough snorted; “they just come here, pick a spot, get buried and pile the stones on top?”

Her voice, trickling like a brook, was starting to charm him, making him think of her, for a nanosecond, without clothes.

“Choose spot, pay bribe to local official, build pile of stones. Otherwise, have to use commercial cemetery. This poster,” she pointed to a billboard at the roadside, “advertising commercial cemetery.”

The plain was throwing off a white haze that was too dense to be morning mist–this was the dust rising as the sun began to scorch the soil. The leaves of the saplings, regimented along the roadside to infinity, were curled and brittle.

“Other side of mountain range is Gobi Desert,” she said, reading his thoughts, “constantly threatening encroachment through passes of Helan Shan.”

“How long before encroachment?”

He took a sip of the Coke and waited. There was always that moment of anxiety when you hide alcohol in a fizzy drink: will the Coke just taste like Coke? Will the little kick not happen? But after a second or two he felt that pleasant clunk in his cortex.

“Probably in our lifetime,” she replied.

He’d spent eight hours in a plane, three hours at Beijing airport, two more flying to Yinchuan, then six hours in a hotel room with no minibar. In that time he had retained just one colloquial Chinese phrase: the words for “fuck me, fuck me”– hooted mechanically by prostitutes in the adjoining room as they entertained a group of officials. And now it was Friday.

Chun-li had drifted back to sleep; Carstairs was snoring next to her, head back, one hairy fist instinctively wrapped around his camera strap. Georgina, their producer, was draped across the whole back row of seats behind them: hair scraped behind a pair of Donna Karan sunglasses, a man’s white shirt, cambric skirt billowing to her ankles, Birkenstocks dangling from her sleeping toes.

Now, through the sun-slant, Brough spotted a flash of colour in the fields: little dots of pink and the silhouettes of human beings moving between the furrows. A few minutes later he spotted some more.

“What’s this?” He gestured to the driver, who’d been on autopilot behind a pair of gold-frame aviators.

The driver laughed the kind of laugh you laugh when somebody you don’t like has been hit by a truck:

“Da-gong;” he chuckled: “Har, har! Da-gong.”

“Chun-li…” Brough whispered.

It was going to be tricky, this. He poked her knee with a biro. She snapped awake.

“Can you tell the driver to stop so we can film da-gong?”

“Da-gong mean migrant worker,” she whispered back, craning her neck to see what he had spotted: “Ah! Da-gong also mean day-labourer.”

“What’s going on?” said Georgina, awake the moment the engine note changed.

“Just pulling over for a quick leg-stretch,” Brough said.

“What have we stopped for, David?” She jerked herself upright.

But he had leapt out of the van and was striding into the field, Chun-li tagging behind him, the tail of his linen jacket flapping in the breeze.

There were about twenty of them in the work-gang, stretched in a line; he could see now that most of them were women, bending and swaying, their backs parallel to the earth. They were wearing headscarves the colour of cherry soup–the Hui minority’s version of the hijab–and swaddled despite the heat in cardigans, chintzy aprons and marigold gloves. A few blokes up front were scraping at the soil with homemade hoes. On a levee stood two men, Han Chinese, identically clad: white shirts, pressed black trousers, comb-over hairstyles–their faces composed as if for a funeral. Chun-li hurried over and began rabbiting at them in Mandarin.

“David, I mean, we’ve got stuff like this already,” said Georgina, stumbling up behind him. The air was thick with the smell of baking earth and melting tarmac.

“You see,” said Brough, ignoring her, “I knew there’d be fucking poverty if we just looked for it. Lying bastards…”

“We don’t know they’re poor, do we? And I’m just not seeing the environmental issue here,” she began–but he said, with studied cruelty:

“You ever worked in a fucking field?”

And then:

“Hey Jimmy!”

Carstairs was swaying towards them under the weight of his tripod, camera and kit-bag.

“Jimmy, look at this. This. Is a fuckin’ money shot, correct?”

Brough made a finger-frame towards the mountains, which would form a tyre-black colourwash against the pink of the women’s headscarves and the dead, white soil.

“It’s not the shots, David,” said Georgina: “It’s…”

“Gimme the stick-mike, Jimmy,” said Brough.

Carstairs handed him a microphone with a radio antenna dangling from one end and a mic-flag with the Channel Ninety-Nine logo at the other.

“Hold on a minute, I’m serious here,” Georgina folded her arms, “It’s a massive drive to Shizuishan and we’ve already done the peasant thing!”

“Yeah,” said Brough: “I-not-poor. I-love-Communist Party. We’ve done lots of that.”

They’d grabbed an hour’s worth of filming in the twilight, on arrival: sheep farmers living amid the ruins of the Great Wall. All of them prepared to say–straight to camera–that they preferred pharmaceutical sheep-feed to the traditional grazing methods; that they would have adopted the sheep-feed anyway, even if the grassland had not died, suddenly, beneath their feet.

“Field bosses say no problem,” announced Chun-li, picking her way across the soil on two-inch heels. “I just tell them we make tourist documentary about Helan Shan and they are not even requesting facility fee: only to emphasise profound respect of CCP for Hui minority and religion of Islam…”

But Brough was already gone, loping towards the work-gang with the microphone held up like an ice cream and Carstairs struggling up behind him.

“This. Land. Good?” Brough shouted to an old guy at the front.

The old guy stopped, leant on his hoe and smiled–not at Brough but into the space above Brough’s head. His skin was Eskimo-brown and his teeth the same.

“Ask him if the land’s any good,” Brough said. And Chun-li began quizzing the old guy in a tone of voice you might use with a retarded kid.

Carstairs snapped the tripod open and clipped the camera into its mount: he had worked with Brough before, in Chiapas and the Niger Delta, so he was used to snatching what could be snatched without constant sound checks and explanations.

“Why is the land so dry?” Brough’s voice became suddenly modulated with concern, now the camera was rolling.

The old guy spoke in short, parched sentences ending with a monotone laugh: “ha, ha, ha”. Chun-li summarised:

“Actually this land quite good–that why two rich brothers decide to buy farms of everyone in area and turn into willow plantation.”

“How much a day do you earn?” said Brough.

After a short exchange she reported:

“Old Mister Jin earning 50 kwai for ten-hour day. Actually that quite good. Only problem is Jin family having to pay 700 kwai for irrigating rice field each week. Therefore, including wages of Little Jin,” she indicated a fat kid standing gormlessly in the background wearing a cast-off army t-shirt, “combined disposable income equals zero.”

Brough turned triumphantly to Georgina.

“Waste of tape,” she sang, under her breath.

“How does he survive? I mean,” Brough paused to leave an editing space: “Whose fault is it that so many people are poor?”

He felt Chun-li go tense as she translated this, but then relax as she heard the answer:

“Old Mister Jin insist he quite rich,” she announced. “Two other sons working in toy factory in Guangdong Province owned by self-made millionaire. Send back wages. Soon Little Jin will also enter toy-making profession.”

“Ahh!” said Brough, arching his eyebrows in mock delight.

“Ha, ha, ha,” said Old Jin.

“Har, har fucking har indeed,” said Brough, to nobody.

“Can we call that a wrap?” said Georgina, not without irony. “Can we get out of this effing field and get on to the next effing city where…”

“But this land is shit!” Brough had grabbed a handful of soil and was crumbling it in front of the old guy’s nose. He was suddenly red-faced and shaking:

“Ask him,” he took a deep breath, “if it’s a Communist country why does he have to pay for irrigation?”

“Da-vid,” Georgina was about to try some neuro-linguistic management bullshit but Brough just tuned it out. He was sweating–sweating whisky-cola it felt like. He could feel the bald patch on his head going the colour of smoked salmon in the sun.

After a long stare at the horizon Old Jin thought of an answer and, with a modest smile, delivered it to Chun-li. She stifled a smirk:

“Old Mister Jin says: Here we eat and drink Communist Party”.

“Wrap!” Georgina sang, eyes rolling–a little bit of mania in her voice as she told Chun-li to tell Old Jin thank-you very, very much and to convey our deepest gratitude please to the field bosses. And Carstairs unclipped the camera and was about to move when Brough said:

“But why do you have to eat and drink the Communist Party?”

There was a beat of silence.

“Sorry don’t really understand question,” said Chun-li.

“What I mean is: can he tell me why they have to eat and drink the Communist Party, because if you ask me, though I’m no expert, the feng-shui round here might be great for the dead but not for the fuckin’ living!”

He could see she thought this insolent.

“Old Mister Jin probably not capable of understanding this kind of question,” she muttered.

“Yes but you understand it, don’t you? You understand why if somebody says they eat and drink a political party it’s sensible to ask them why? If I asked you, you could understand it so why can’t he?”

Carstairs, noticing that yelp in Brough’s voice that always bubbled up when he was about to lose control, and wondering despite the early hour about the looseness of some of Brough’s gestures, said:

“I think we’ll need cutaways.”

But Georgina said don’t waste tape; and Brough threw some convoluted sentence at her sprinkled with obscenities; and Chunli flinched at the f-words, which they were spitting at each other now with a violence they just don’t warn you about at English lessons. And Old Jin just watched and stared.

While all this happened Carstairs shot a sequence that they could use as setups if they had to.

He framed the master-shot wide, with the work-gang toiling at the bottom, blurred by the heat and dwarfed by the mountain range. Then he shot the women in close-up: the pink of their scarves throbbing neon against the drabness of the mountains; the rough wool of their cardigans, their cracked lips, their tanned and florid faces reminding him of Afghanistan.

One woman stole a smile into the camera and Chun-li told her to stop but Carstairs said no, let her. She looked sixty; others were teenagers. There were no adults of working age here at all.

Then he pulled a sneaky two-shot of the field bosses:

“How did these two miserable buggers make their money, d’you think?” he muttered to Chun-li.

“Maybe win lottery, or discover Rare Earth deposit beneath farm, or exit stock market at top of curve,” she began, but Carstairs interrupted:

“For fuck’s sake!”

He made throat-cutting gestures at Brough and Georgina on the other side of the field, instructing them to “shut it!” as their shouting was ruining the natural sound.

“There’s nowhere for it in the fucking structure,” Georgina was yelling at Brough.

“Well fuck the fucking structure!” His knees were flexed with anger, fingers splayed, cowboy boots knocking the tops off furrows as he paced around in the soil.

“It’s been signed off! New York have been all over it for a week!”

“Alright I’ll phone them!”

He waved his Blackberry into her face as a kind of threat.

“Go ahead. I’m sure New York would love to hear from you!”

Brough’s mistake had been to use the words “war crime” in a live report from Gaza, after the Israelis had managed to drop white phosphorus onto a school, followed by a series of world-weary generalisations about Hamas, Al Jazeera, Tony Blair and indeed the entire region. The Channel’s bosses had pulled him off the story within six hours, citing post-traumatic stress. They’d moved him into “long-form”: soft, people-centred reports to fill the half-hour of current affairs they were supposed to air each week, between the freak shows and make-over programs.

“But look at it!”

He made an expansive gesture at the field, the work-gang, the bosses on the levee:

“Look at these two – Gilbert and fucking George! You could tell the whole story here if you wanted to! I bet…”

He checked himself. There was no point. He was feeling shaky, dehydrated.

“So you’re the expert on frickin’ China now!”

Georgina had sensed his deflation. As he hunched his shoulders and turned away she ventured:

“You know Twyla actually speaks Mandarin?”

He muttered an obscenity about Twyla, their boss in London, which Georgina ignored.

“It’s all in the structure and the structure’s signed off, David.”

He forced himself to laugh. At the situation. At himself. He was giggling uncontrollably by the time Chun-li summoned the courage to approach him:

“Why does that old bloke keep staring above my head?”

“Actually quite amusing,” Chun-li, relieved, let herself giggle too:

“According to folk religion believed by uneducated people, spirits of ancestors hovering everywhere, just above our heads. Old Mister Jin tells me he is wondering if Correspondent Brough being advised by mischievous spirit.”

Brough’s rule was never to drink while working on a serious story, so for the past six months he’d been forced to hike his alcohol intake to lifetime record levels. Now he felt like hiking it some more.

2

There was a condom in the wastebasket. No doubt about it: the smell of burning rubber was unmistakeable. Likewise the smirk on Propaganda Chief Zheng’s face, the gold microfibres clinging to the knees of his slacks, the mortified look on Sally Feng’s face as she left the Chief’s office brushing bits of carpet out of her hair.

Li Qi-han straightened himself and tried not to think about Sally Feng doing it with the Chief.

“What’s to report?” Zheng gestured into the air with his cigarette.

Li stood to attention, feeling the hair on his shins crackle with static from the Chief’s carpet – a brand-new red-and-gold creation interweaving the stars of the national flag with images of railways and construction cranes.

He clutched the intelligence file tight under his arm, fighting back nausea and dread.

“Nothing today, Chief.”

Zheng, his feet crossed on the desk and head wreathed in smoke, wore his usual outfit: striped polo shirt, fawn slacks, tweed jacket and Playboy-logo belt, black-weave loafers and hair dyed the same colour as President Hu Jin-tao’s: latex black.

Li himself was wearing a Nile green tennis shirt and caramel-coloured chinos: he despised designer belt-buckles but in preparation for his exam he had taken to wearing a cheap, milled-steel number with a rip-off of the Versace “V”.

“You look a bit peaky today, Deputy Li,” Zheng teased him.

“Peaky? Not me!” said Li. “Ready for action, Chief!”

Li’s grandfather, a coalminer from Wuhan, had used to insist: a miner never misses work from being slaughtered with drink, as a point of honour. Li had arrived for work that morning slaughtered with drink but was not about to betray the family tradition.

“Nothing at all in the intelligence?” Zheng insisted.

“Squat.” Li bullshitted; “We’ve got to organise a morality lecture at the High School because of what those kids keep doing on the Internet. After that, nothing until the,” he angled his head and paused in the obligatory way, “twentieth anniversary…”

“Okay, get lost then.” Zheng wafted a lazy circle of smoke in the direction of the door.

Li quit the room agitated. He’d spent most of last night at the Tang Lu branch of KTV, moving deftly through his Frank Sinatra repertoire into a medley of Chinese love duets with Sally Feng. Around 4am he had been kicked out of a taxi, alone, on the wrong side of the river in the brick-kiln suburb towards Wuhai, stumbling around in the shit-filled alleyways and being sick. He had stared tearfully at the Yellow River wondering whether its spirits were trying to communicate something. Now, six hours later, the throb of white alcohol behind his eyes was communicating the need to lie down.

He marched into the general office and slammed the day’s orders onto the desk in front of his subordinate, Belinda Deng. She was related to some disgraced Shanghai party boss: wide-faced, supercilious, constantly trading shares via text message. Much of Li’s workday was devoted to making Belinda Deng look down at her desk and not up, insolently, at himself.

“Different shit, same day,” he said.

Her face barely registered his presence.

Li slouched over to the hot water machine, refreshing the leaves in yesterday’s tea flask. Everything in the office smelled plastic. The air-conditioner was making his neck hairs stand on end and his brain ache. His under-arms reeked of aerosol. Everything was, in this sense, normal.

He studied Sally Feng’s broad hips as she twisted in her seat to keep her phone conversation private. He studied the wall map of Ningxia Province, with marker-pen lines indicating areas of support for crazy imams in the south, where water had run out and Islamic fundamentalism had run in. An orange paper dot marked the location of Tang Lu Industrial Suburb. He would soon be out of there for good.

He felt shivery, bilious and weird. Usually when he got this paranoid after drinking it was because there was some kind of shitstorm on the political radar screen: an official visit, the upcoming trial of a mining boss. But the notes today said nothing. His computer screen said nothing, except for the usual “have-a-nice-day” from the Communist Party Discipline Section. There was nothing abnormal on the horizon at all.

3

“Oh my God, this is Mordor!”

Georgina’s voice jerked him awake.

Brough could tell from the slant of the light that it was late afternoon. He had dribbled Coke-coloured spit onto his shirt. He desperately needed the toilet. They were at some kind of motorway toll, wedged into the middle of a long queue of coal trucks.

“D’you think they have a toilet here?” he muttered.

“No look, it’s fucking Mordor! You ever seen anywhere like this?”

Brough craned his neck to follow the direction of Georgina’s stare. It was the city he couldn’t pronounce: Shizuishan. He let his eyes drift across the skyline, swathed in brown haze, arrayed with smokestacks, cooling towers, petro-chem rigs and blast furnaces. Implausibly vast, as if every industrial city in Britain had been cut and pasted into one mega-city.

“Yeah,” said Brough, “Belgrade after the Septics bombed it. Listen, I’m desperate. Chun-li, d’you think I can just er, go to the toilet on the side of the road?”

“For urinating or defecating?”

“Urinating.”

“Chinese men will do urinating under table at restaurant if nobody looking.”

He lurched over the crash barrier and into the roadside scrub, stiff with jet-lag. The throb of diesel engines and the stench coming from the truck exhausts touched a childhood memory: his father had been a lorry driver. He unbuttoned his fly and relieved himself into the nettles.

“Smell that?” Carstairs was beside Brough now, legs braced, unzipping his trousers.

Brough let his nostrils flare against the smell of fresh coal.

“Fuck, that takes you back!”

Carstairs was pushing sixty: he’d been a long-lens snapper in Fleet Street, a cameraman in various wars and now made his money out of corporate videos plus–as he had put it to Brough on arrival–“shit like this”.

“That’s where all our bleedin’ jobs went, innit?” he gestured with his chin to the skyline.

Brough nodded.

“What’s up with that bird?” Carstairs ventured.

Georgina had once been breezily at home in the foreign correspondents’ world of drink, late night bitterness and casual sex. But she’d quit, gone into the indy sector, made some money and now had a boyfriend in New York: hedge fund guy with a saltbox in Connecticut and a reconstructed septum.

“She’s made a documentary about the Yangtse Dolphin,” said Brough; “She knows all there is to know about China.”

In the van, Chun-li was having a high-speed Mandarin conversation with her cellphone, which Georgina had learned to read as a sign of trouble.

“Slight problem with Shizuishan wai-ban,” she announced.

“What?” Georgina began tugging at her handbag to fish out the schedule. The city’s foreign affairs department, known as the wai-ban, were supposed to escort them to a three-star hotel, a banquet and the inevitable smoke-hazed drinking session to scope out tomorrow’s interview with a senior party guy.

“Senior Party Guy will not receive interview.”

“Why not?”

“Urgent business trip to Beijing.”

“What do the wai-ban advise?”

“Move to next city.”

Chun-li’s voice betrayed that she knew how ridiculous it sounded. But that was what they’d said.

“So hold on a minute,” Georgina’s voice began to quaver slightly, “who’s going to give us the interview about environmental policy?”

“Difficult to say,” said Chun-li, as Brough and Carstairs swung themselves into the van. Georgina made her eyes bore through Chun-Li’s tinted shades, searching for some kind of logical outcome.

“Are you telling me these guys can just cancel an interview we’ve taken six months to set up at half a day’s notice?”

“Extremely possible,” said Chun-li.

“For a major TV program specifically sponsored by the Chinese government?”

“Quite usual.”

Channel Ninety-Nine had scheduled a special edition of its flagship talk show, Live at Nine with Shireen Berkowitz, to be filmed “as-live” from the top of a skyscraper in Shanghai. The aim was to mark the twentieth anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, or “Events” as they’d agreed to call them. “Let’s do the issues that matter today – not twenny years ago,” their boss, Twyla had told them. That meant everything except torture, democracy and human rights.

Brough’s job was to front a seven-minute report about the Party’s fight against environmental depredation in western China. They had to be in Beijing by Wednesday to edit and feed it to Shanghai. Brough’s presence was not required in Shanghai; in fact his presence anywhere near a live broadcasting position had been actively discouraged.

Georgina flicked through her Lonely Planet:

“Let’s get to the hotel, have a beer and work on it.”

“Also another slight problem,” it was Chun-li’s voice quavering now. Brough, Carstairs and Georgina caught the quaver and began to stare at her intently:

“Three-star hotel in Shizuishan cancelled our reservation on advice of wai-ban chief.”

“Well fuck the wai-ban chief let’s rebook it ourselves,” said Georgina.

“I already try that, they say: No Vacancies.”

“Well book another one!” Georgina exploded.

“Already tried that also.”

There was silence.

“No western-standard hotels apart from already-un-booked Three Star Beautiful Pagoda, No Vacancies. No other hotels at all listed.”

“Where do the foreign businessmen stay?” said Brough.

“Not very often in Shizuishan.”

Georgina screwed her eyebrows into a single eyebrow and studied her guidebook.

“See this? Where’s this town here?” she tapped the page with her finger and thrust the book under Chun-li’s nose; “It says there’s a decent hotel in this place. But I can’t find it on the map.”

Chun-li produced a Chinese atlas and flicked through the pages, settling finally on one that showed only a blank expanse of desert and a precise, square grid of conurbation in the middle of it, with only one road in and out. It was a place she’d never heard of, about an hour’s drive north.

4

A joke among steelworkers in Shizuishan runs: first prize in the trade union lottery is a week’s holiday in Tang Lu, second prize two weeks. But that does not bother Tang Lu residents. They laugh at it out of a kind of pride.

Li Qi-han, who had clocked off and was headed for the massage parlour, hated Tang Lu. Despite his mining ancestry he was a Beijing boy to his core and the locals knew it: from the absence of that happy cynicism that Tang Lu folk carry around on their faces; from his lack of resignation.

Li’s face was, in fact, permanently annoyed. Annoyed at Sally Feng, annoyed at the Chief, annoyed–above all and perpetually–at his dad.

Fair enough; in 2006 things had looked promising: there’d been talk in the Party newspapers about compensation for former “rightists”. Grandfather Li had been a notorious rightist: jailed in 1956 for writing a wall poster against the Soviet invasion of Hungary–and never seen again. Li’s dad had signed a petition requesting lump-sum compensation for the surviving relatives of persecuted rightists. But a year later, after working its way around the desks of various cadres, the whole rightist rehabilitation campaign had been deemed, itself, “rightist”.

Li’s dad, a leftist in the sixties but now running a self-help book imprint, had suddenly been hit with a massive tax demand. Li himself – who’d had no idea what his dad was up to – got called into the discipline section at the Beijing Olympics Propaganda Bureau and told to pack his bags for Ningxia Province.

So now, two years on, he wandered through the backstreets of Tang Lu, headed for the massage parlour: pissed off with the Chief, Sally Feng, his dad, life itself–and still suffering from this strange, unsettling apprehension.

Soon he would sit an exam in The Important Theory of Three Represents: “Just demonstrate some basic knowledge of Jiang Zemin’s contribution to Marxism and you can fuck off back to Beijing,” Zheng had told him. But studying the Three Represents had made Li become irritable, agitated: so agitated that, for weeks now, he’d needed to drink white alcohol to get to sleep.

On top of that he had, for some reason he did not care to rationalise, erected a shrine to Grandfather Li on the mantelpiece in his apartment, consisting of Grandfather’s last known photograph, in PLA uniform, and his Type 51 pistol from the Korean War, a family heirloom. Li had been burning large handfuls of “spirit money” on this shrine most nights.

The backstreets of Tang Lu were teeming with that life you barely see in Beijing anymore. A woman lifted her toddler to pee into the gutter. The tea-seller smiled, beckoning Li to her table of gleaming steel pots: this one to calm his inner fire, this one to stoke it up. In the hairdresser’s, one prostitute was combing the hair of another. Each had a Motorola flip-phone wedged between chin and shoulder: the one gossiping with her sister in Shenzhen, the other placing a bet on tonight’s basketball game with an illegal bookmaker.

Kids wrestled in the street dirt; miners’ wives engaged in hard-faced, emotionless gossip. In an alley behind the hairdressers’ stood the neon-lit frontage of the Happy Girl Massage Parlour. Li slipped silently through the door, barely nodding to its proprietor, Mrs. Ma.

He liked to keep his massage activities discreet and preferred the Happy Girl precisely because it was the kind of place party officials and local government stooges would avoid. Here it was mainly freelance mining engineers, Mongolian drug dealers with buzz-cut hair and other nouveau riche scum.

He killed his cellphone as the serving girl steered him into the booth. He had his shirt off, neatly folded on the chair, by the time she’d brought him a bottle of Snow beer and laid it respectfully on the side-table next to a basket of condoms and a basket of salted peanuts.

There was a mirror: he was in good shape for 27, if a little scrawny. His pudding-bowl haircut marked him out as a dutiful Communist. He waited for the girl to leave before getting his pants off and laying face down on the massage table. Who would Mrs. Ma send in? There was always the frisson of waiting to find out.

The door handle clicked. He could tell from the swish of her tunic, the clunk of her sandals that it was Long Tall Daisy; her breath, as always, a little bit rancid with catarrh but her fingers already trailing gently up his leg in compensation for that.

He would come back to Mrs. Ma’s place for a full night with Long Tall Daisy before he left Tang Lu. He made a mental note of that as she started the CD – eerie, orchestral waves montaged with underwater whale noises – and lit an incense stick. Though his hangover had gone he still felt, for some reason, jumpy.

5

This is what they see on the tape when they finally get to view it:

Vertical spectrum-bars with a high-pitched whine, the word CARSTAIRS in a digital font, and timecode in the corner of the screen beginning 03.00.00. That means the start of tape three.

The opening shot shows the inside door of a Ruifeng van. The cameraman has hit the record button to run the camera up to speed as he mikes-up the reporter. Now the sound channels kick into life, jolting the graphic equaliser.

“Hold on David, I’m not really sure we have time for this.” It is Georgina’s voice, querulous but resigned.

“Maybe I get out first,” Chun-li suggests, off camera. “Pollution very sensitive issue in towns like this.”

“I’m not surprised!” It is Carstairs, his voice betraying that alert distraction that takes hold of cameramen as they begin checking their levels, their battery power, stashing extras of everything into the pockets of their trousers.

“I think I’d better stay with the van,” Georgina suggests.

“Yeah, no worries. Just me and Chun-li.” It is Brough’s voice, calm and languid like it was when US Marines pointed a .50 cal machine gun at him from a Blackhawk, deep to his groin in water, one humid afternoon in New Orleans.

The camera swings up as they bail out of the vehicle. Brough smoothing his sandy hair, his jacket crumpled; Chun-li wobbling around in the dirt on her unsuitable heels.

It’s the very last light of the day: the colours are the warm rust of a traditional Chinese hutong. Low brick shacks topped with curved, medieval roof-tiles; an unpaved road where shaven-headed kids play stone-throwing games in bright yellow cardigans and acid blue T-shirts.

Chun-li leaves the frame and heads up the street but the camera stays on Brough, who keeps squinting at something in the distance, nervously, and whispering to himself: “Shit!”

There is, in the picture, a strange haze to do with more than just the fading light. The camera swings upwards; Carstairs’ cockney grimace blocks the sky out and is in turn blocked out by a chamois leather as he tries to wipe dust off the lens.

“Yes they will talk,” says Chun-li, at 03.02.27.

“Did you explain we are a Western documentary team?” says Brough.

“Yes they say no problem. They very angry.”

The camera follows Brough and Chun-li up the street. Carstairs pulls a nice slow pan off them to a dirty kid, its smile revealing only half the normally allocated number of teeth.

Now Brough walks up to a group of local people who are looking a mixture of puzzled and wary:

“David Brough, Channel Ninety-Nine News.”

Brough shakes a few hands while Chun-li does rapid-fire introductions, and then clears his throat:

“Is the air always as bad as this?”

Pause, translation.

They all start shouting at once. There is a woman in a Qing-dynasty silk jacket, an old man with a face the colour of lead, two middle-aged men and a yappy housewife. Kids skip around them to get into shot. Carstairs goes in tight, the lens out to its full wide-angle making the faces loom, distorted, at the edges. The camera mic picks up the sound of what they’re saying and Chinese listeners will, later on, go pale once they make it out.

Man with grey face: “It’s like this every night. During the day they switch it off so the sky looks blue. But every night at seven o’clock it comes over here. You can tell the time by it.”

Woman with silk jacket: “We have to shut our doors and windows. Every night.”

Yappy housewife: “You journalists should launch an investigation into it!”

Brough tells Chun-li to tell them to slow down and speak one at a time, then he has three goes at asking the same question, his voice tight with adrenaline:

“Have you not complained?”

Man, grey face: “We complained but nobody gives a shit! My chest is tight!”

Chun-li translates: “We have contacted the authorities but nobody seems to care.” You can tell from the tremor in her voice she knows how close they are to saying something bad about local officials on camera.

Silk-jacket woman: “If you breathe this stuff you feel like vomiting and if its windy, your eyes burn.”

And she clears a small space around herself and acts out the final agonies of her dead mother, coughing into her hands and struggling for breath.

Chun-li explains that it’s a battery factory that’s the problem.

“Where?” says Brough.

Everybody points into the distance. The camera – Carstairs is a genius – swings slowly round in a very useable one-eighty degree pan and pushes in, holding steady, to the flaring gas pipes that had made them stop the van in the first place.

It is a modern plant, big slabs of concrete wall and gross, concrete chimneys painted red and yellow, the whole base of the complex shrouded in white vapour.

Off-camera there is more uproar, the crowd shoving each other aside to present their case: “My kids are choking on this shit!” “My son is a dwarf!” “I ran the marathon once but look…”

“Chun-li what are you doing?” Brough asks.

“Just wait a minute. I need to type word into translator”

The camera goes tight on the small translation machine in her hands. Her nail job catches the last of the natural light.

“Chlor-,” she says, then after a long pause: “ine”. “Pollution contains chlorine.”

Brough says:

“How do we know it’s chlorine? It could be just steam.”

Chun-li translates and the crowd – it has grown to a small crowd now–goes slightly wild. They shout at him in a cacophony of anger.

“This factory very notorious polluting factory owned by brother of local city mayor; whole cemetery is full of residents dying below age of 50,” Chun-li translates.

Carstairs is getting cutaways now, of kids, dogs, crumble-walled shacks. A two-shot of Brough and the grey-faced man:

“What do you want the authorities to do?”

“They should move us like they promised,” the man begins, but Carstairs whip-pans off him to a woman standing at the edge of the crowd who is staring coldly at Brough, barking questions at him that he is not hearing.

“This lady want to know who you are,” Chun-li’s voice conveys the clear subtext: “let’s leave”.

“Good evening madam: David Brough, Channel Ninety-Nine News–and whom do I have the pleasure of addressing?”

“Do you have permission to be here?” the woman asks.

It’s Busybody Guo, head of the district management office. She’s been watching the 7 o’clock news bulletin, but luckily with the sound turned down or she would not have heard the commotion.

“Yes of course, we are here with the full permission of the Ningxia Province wai-ban,” says Brough, using a supercilious form of English both he and Carstairs know they will cut out in the edit, especially when he adds: “We have been personally invited by Premier Wen Jia-bao to tell the story of the fine efforts of the Communist Party in the sphere of environmental protection.”

Busybody Guo spins on her heel, flipping her mobile open as she stamps back into the alleyway.

“Ignore the bitch,” somebody shouts.

“Piece to camera,” Brough mutters and breaks away from the group, taking up position with his back to the factory, which is now spewing vapour, thick and greenish, towards them. It’s already started to obscure some of the roofs and reduce the flames from the chimneys to a sickly yellow glow.

“Here in Western China, the official story is…”

“Wait ten seconds,” says Carstairs.

Brough checks his reflection in the camera lens, sees the approaching cloud behind him and understands. He takes a breath, drops his shoulders and smiles wearily.

“Go” says Carstairs.

“Here in Western China the official line is that pollution’s been outlawed. But the residents tell a different story. Every night, they say, a cloud like this comes over the fence and makes the air impossible to breathe. They say it contains chlorine. In the west they’d be able to call in scientists to test the air. Here all they’ve got is the Communist Party, and the local leadership seems more worried about our presence, than about this…”

He turns, with only mild theatricality, to the tsunami of vapour that is now a few yards away and then turns back to face the camera as the cloud engulfs him.

“David Brough, Channel Ninety-Nine, Western China.”

“Wrap,” says Carstairs. The camera drops to knee level and they walk quickly up the smog-wreathed alleyway towards a van with a blonde woman gesturing at them out of the side-door.

“What the fuck?” she is saying: “I’m choking to death here!”

The camera goes back to its starting position, the lens wedged up against the door. Slamming sounds are heard and the engine revs.

“What did you get?” Georgina’s voice is a mixture of annoyance and excitement.

“The fucking works. This cloud is full of chlorine,” says Brough.

“Is that dangerous?”

“No idea. Wait till you see the tape. Do you think that woman was pissed off enough to phone the pigs, Chun-li–I mean the police?”

“Pollution very sensitive in this part of China. Maybe she will not want trouble for herself. Better get away from area. Also switch tapes.”

The screen goes blank. The timecode says 03.23.34: that’s twenty-three and half minutes on tape. Two gigabytes on disc, max.

6

Xiao Lushan’s eyelids were becoming soft under the damp flannel; on the stage the dirty-joke comedian had given way to a monologue artist. Xiao’s feet were being massaged by a demure girl. And his cellphone was on vibrate.

Friday night, for Police Superintendent Xiao, was sauna night. Sprawled in the next armchair, snoozing in a pair of yellow-stripe pyjamas, was Zhou, Secretary of the Tang Lu chamber of commerce. On the other side, flashing a smarmy smile at the tea girl was Sheng, editor of the Tang Lu Daily (founded 1958), wrapped in a cotton robe.

Soon the monologue artist would give way to a drag act and, feigning distaste, the three men would put their slippers on and glide, cracking timeworn jokes, up the escalator to the cafeteria, where they would make menopausal small-talk with the waitress, slam dice cups on the table, shout chaotically for Chairman Mao’s Red-braised Pork and slurp green tea.

This was Superintendent Xiao’s routine. No other cops would dare show up at the Tang Lu Public Sauna Number One on a Friday night–except his driver, who was outside in the command vehicle, a BMW X5 with three digital comms antennae.

By Friday night all the drunks and fighters from the past weekend would have been processed to pre-trial detention centres; let somebody else take the rap if they got mistreated. Most strikes and industrial accidents happened, as every good cop knows, towards the beginning of the week. And any politically dodgy sermons at Friday prayers were a problem for the State Security Police, not Xiao.

Only “mopes” were the reason Xiao kept his cellphone on at all. “Set phasers on stun,” the three men always joked on arrival.

“Mope” was a word he’d picked up from The Wire–Series One, which the command group at the station had been watching on pirate DVD with Chinese subtitles. It was satisfyingly close to the Mandarin word for con-man. Ningxia Province was home to all kinds of mopes, some driving SUVs, others zipping between the hairdressers, karaoke bars and acupuncture shops on little motorbikes. They would stare into space violently when the traffic cops busted them. Whether it was drugs, betting, prostitution – it was always executed with a profound failure of imagination: disorganised crime, Xiao called it.

He’d busted a whole gang of mopes last year, supplying trafficked women to a “ballroom” servicing the flint quarries in the Helan Shan. A spectacular bust – even rescued three of the girls alive and got a mention in the People’s Daily.

He was one pip short of Commissioner and with his good connections–and bearing in mind the rule that says one out of every three officials in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Province actually has to be a Hui Muslim, and not, like Xiao, Han Chinese–he would one day make it.

“Hey Spock, your tricorder is registering signs of life!” said Zhou.

Xiao’s phone was a fat Nokia; its gold-lacquered fascia decorated with fake gemstones in the shape of the Taj Mahal. His daughter had given it to him when she’d left for Beijing and, though he knew it made other police officers snigger behind his back, he couldn’t bear to change it. He had taped her photograph onto the back of the handset. Now, as he peeled the flannel off his forehead, it was her face he could see vibrating its way towards the edge of the table.

He leant wearily across, motioned the massage girl to leave his feet alone and grabbed the phone.

Xiao Lushan is a big man, so when he shot upright in string vest and shorts, purple-faced, neck veins protruding–like a giant walking penis–scattering pumpkin seeds and frightening the massage girl rigid, the whole room fell silent.

The duty officer had been too scared to call so had put the entire situation into a text message:

“Foreign media in Tang Lu East Village. Threat to social order. Await instructions.”

Xiao’s face went into the shape of a vengeful warlord’s face, like in a TV shouting-drama:

“I’ll give them a threat to social order,” he said between clenched teeth.

“We will eat your portion of Chairman Mao’s Red-braised Pork,” Zhou chuckled.

“Somebody is going to regret that they were born,” newspaper editor Sheng sniggered, reaching for what was left of the pumpkin seeds as Xiao strode–wordless and with fists clenched–toward the changing room.

7

At Tang Lu Police HQ he found the control room deserted apart from his deputy, Tong, and the riot-squad leader, Hard Man Han:

“Why were we not told the foreign media were in Tang Lu?” Xiao yelled.