7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

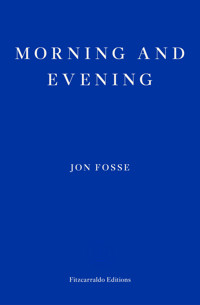

- Herausgeber: Fitzcarraldo Editions

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Scenes from a Childhood is the latest collection of stories by Jon Fosse, one of Norway's most celebrated authors and playwrights, famed for the minimalist and unsettling quality of his writing. In the title work, a loosely autobiographical narrative covers infancy to awkward adolescence, unearthing the moments of childhood that linger longest in the imagination. In 'And Then My Dog Will Come Back To Me', a haunting and dream-like novella, a dispute between neighbours escalates to an inexorable climax. Taken from various sources, the texts gathered here together for the first time demonstrate that the short story is one of the recurrent modes of Fosse's imagination, and occasions some of his greatest works.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

‘Jon Fosse is a major European writer.’

— Karl Ove Knausgaard, author of My Struggle

‘Jon Fosse is less well-known in America than some other Norwegian novelists, but revered in Norway – winner of every prize, a leading Nobel contender. I think of the four elder statesmen of Norwegian letters as a bit like the Beatles: Per Petterson is the solid, always dependable Ringo; Dag Solstad is John, the experimentalist, the ideas man; Karl Ove Knausgaard is Paul, the cute one; and Fosse is George, the quiet one, mystical, spiritual, probably the best craftsman of them all… His writing is pure poetry.’

— Paris Review, from an essay by the translator

‘Fosse has been compared to Ibsen and to Beckett, and it is easy to see his work as Ibsen stripped down to its emotional essentials. But it is much more. For one thing, it has a fierce poetic simplicity.’

— New York Times

‘With its heavy silences and splintered dialogue, his work has reminded some of Beckett, others of Pinter.’

— Guardian

‘Undoubtedly one of the world’s most important and versatile literary voices.’

— Irish Examiner

‘He has a surgeon’s ability to use the scalpel and to cut into the most prosaic, everyday happenings, to tear loose fragments from life, to place them under the microscope and examine them minutely, in order to present them afterward… sometimes so endlessly desolate, dark, and fearful that Kafka himself would have been frightened.’

— Aftenposten

SCENES FROM A CHILDHOOD

JON FOSSE

Translated and selected by

DAMION SEARLS

CONTENTS

SCENES FROM A CHILDHOOD

IT’S MAYBE FOUR O’CLOCK

It’s maybe four o’clock when Trygve and I go out to the old barn. My grandfather built this barn but now it’s falling apart, the unpainted planks in the walls are rotting away, there are holes in the wall you can see through in some places and a couple of roof tiles lying in the nettles, three more sticking out of a puddle of mud. A rusty hook is hanging from the door-frame. The door is hanging from the door-frame too, attached with hay-baling cord, swinging crookedly. A warm summer day, afternoon. Trygve and I sit on a large round stone a few yards from the barn. There are plastic bags under our legs with our lunches inside, slices of bread with brown cheese, we each have a soft drink. It’s hot. We’re both sweating. Mosquitoes are buzzing round our heads.

I JUST CAN’T GET THE GUITAR TUNED

I just can’t get the guitar tuned and the dance is about to start. There’s already a big crowd in the room, most of them people involved with the event and their friends and girlfriends, but still a lot of people, when I look up from the shelter of the long hair hanging down over my eyes I see them moving around the room. I’m bent over my guitar, turning and turning a tuning knob, I turn it all the way down and the string almost dangles off the fretboard, all forlorn, and then I strum on it while I turn the knob up, up, I hear the tone slide higher, I strum on two strings, now is this right? no, it always sounds a little off, doesn’t it, and I turn it more, I turn and turn, up and down, I turn it and turn it and the drummer is pounding for all he’s worth and hitting the cymbals and the bassist is thumping too and the other guy on guitar is standing there strumming chord after chord and I just can’t get this damn guitar in tune. I turn the knob more, and the string breaks. I push my hair back and shout that the string broke. The others just keep the noise going. I unplug the guitar and go backstage, I have spare strings in my guitar case. I find a new third string. I change the string, turn the knob until the string is on. I walk back onstage. I plug the guitar in again and start tuning it. I can’t hear anything. I shout for the others to stop playing. They stop. I try to tune the guitar. I can’t do it. I ask the other guitarist to give me the note, he plays a G on his third string. I turn the knob.

Little more, he says.

I turn it a little more. I look at the other guitarist and he shakes his head a little. I turn it a little more, strum the string. He looks up, stops, listens.

Little higher, he says.

I turn it a little higher and strum.

Little more, he says.

And now it starts to sound right.

Almost there, he says. Maybe a little more.

I turn it a little higher and strum.

Little lower, he says.

I turn it down slightly and strum.

Damn it, he says. Take it all the way down, we’ll try it again, he says.

I turn the knob all the way down. He plays the open third string on his guitar. I start to turn the knob up. I hear it getting closer. It’s getting closer. I see the other guitarist nod. I turn it a little more. And now it sounds right, almost perfect.

Almost, the other guitarist says.

I turn it a little more and now it’s off, I turn it more and I hear it getting closer again. A little more.

Careful now, the other guitarist says.

I turn it a little bit more. And I hear the string break.

Fuck, I say.

Go get another one, the other guitarist says.

I go backstage again and go to the guitar case to get another string. But I don’t have any more third strings. I shout and say I don’t have any more third strings, I say I need to borrow one, and the other guitarist goes to his guitar case and looks for a string. I see him put one knee on the floor and dig around in his guitar case and look for a string. He looks at me.

I don’t think I have one, he says.

He digs around in his guitar case some more. He gets up and shakes his head.

Nope, he says. No G string.

Then I guess I’ll have to play with five strings, I say.

That’ll probably work, he says.

People are already here, I say.

That’ll work, he says.

THE AXE

One day Father yells at him and he goes out to the woodshed, he gets the biggest axe, he carries it into the living room and puts it down next to his father’s chair and asks his father to kill him. As one might expect, this only makes his father angrier.

IT HAS STOPPED SNOWING

It has stopped snowing. Geir and Kjell are out in the new snow but they’re not going skiing, no they’re busy with their snow shovels, pushing the snow around and beating it down flat and hard. I’m standing at my window spying on what they’re doing out there. I ask my mother if I can go outside and she says OK. I bundle up, gloves and everything, and go outside. I run over to Geir and Kjell and ask them what they’re doing and they say they’re going to play car and make streets and a tunnel and everything in the snow. I run home and get two cars. I come back and Geir and Kjell have finished with the snow shovels and they’ve already started working on the construction. And then Geir and Kjell and I build a tunnel, and a garage, and a house. This is going to be great. Geir loads snow onto the truck with an excavator. Kjell drives the snow in the truck, then dumps it out. I build a road. We are working and building. We don’t know what will happen next but we crawl around in the snow, humming and whistling, driving and dumping. Snow is falling steadily on us, light and white, so that the road has to be cleared again and again. We work and build and clear the road. Time passes, but we don’t notice. We plough the road and gravel it with the lightest new snow. We don’t notice that some slightly bigger boys, boys we barely know even though they live only a few houses away, have come walking up to us through the yard. The boys don’t live far away but we don’t know them. They stand and look at us. They ask what we’re doing, and we say we’re playing car. They ask if they can play too, and we hand them our cars, our excavator. Then we stand and watch the other boys play. They yell louder and push the wheels down into the road, they laugh and shout.

Crappy road, they say.

You can’t fucking drive on a road like this, they say.

They have to repair the road, it’s a bad road, Geir says.

You can’t fucking repair a road like this, they say.

These road workers are useless, they say.

Making such a crap road, they say.

I want my car back, Kjell says.

Your crappy car, they say.

That car’s useless too, they say.

It’s all a bunch of shit, they say.

What’s that? they say.

A car park, Geir says.

Huh, a car park, they say.

You can’t park there, they say.

FORGET IT

Let’s forget it, Finn says, and he sits right down on the ground.

It’s too hot now, Asle says. We can’t chop any more wood, he says.

These damn spruce bundles, Finn says.

Let’s do something else, Asle says.

And Asle goes over to Finn and sits down next to him.

What do you think ol’ Haug would say if we just leave, Finn says. Asle doesn’t answer.

He can say whatever he wants, he says after a while.

I’m not sure he’d notice right away, Finn says.

Let’s leave, Asle says.

And go where? Finn says.

The fjord? Asle says.

In your boat? Finn says.

We could do that, Asle says.

And then Finn says Let’s do it. And Finn and Asle get up and climb down through the quarry, through the bushes, down to the road, Asle and Finn have found themselves a summer job clearing away the brushwood from a spruce orchard so the nasty little shrubs have enough room and get enough light, the copse is a couple of miles outside the village, in a quarry above the road that runs from the fjord up to some farms all the way by the tree line. Finn and Asle climb down through the quarry.

We left, Finn says.

We just left! Asle says.

POTATOES AND ONIONS

I am sitting in the living room with my grandmother. Since she’s recently got a new radio, I sit and turn the dial from station to station, and on one of the stations there’s usually music you can’t hear anywhere else, slow music with long dark guitar solos, no singing, no big fuss, music that just is, and between these slow dark guitar solos someone speaks a language I don’t know, in any case it’s not English, I can understand a little English and it’s a language I don’t like.

I find the station where they play those long dark guitar solos, and I sit in front of the radio and listen. My grandmother, who I love, is sitting in the armchair where she usually sits, she’s looking out the window, I don’t know at what, but she’s sitting there looking out at the fjord, I think, anyway I always look at the fjord when I sit in that chair. I’m listening to the slow dark guitars. My grandmother sits looking out at the fjord.

Are you hungry? my grandmother asks.

I nod and my grandmother says that since it’s Saturday she can make what they used to make on Saturday evenings when she was little, then she goes to the kitchen. I listen to the slow black guitar music. I hear the fat start to sizzle in the frying pan. I lean against the kitchen door and see my grandmother standing in front of the kitchen sink chopping onions.

Bacon and eggs, potatoes and onions, my grandmother says.

I go back into the living room. I sit down in the chair in front of the window and look out at the fjord. I hear the sizzling from the frying pan and the slow guitars.

MY GRANDMOTHER IS LYING IN BED

I.

My grandmother is lying in bed, she can’t talk any more. There’s another bed along the other long wall and someone’s lying there talking nonsense all the time. I’m sitting in a chair next to my grandmother’s bed. My hair is so long, down over my shoulders, that it reaches her bed when I bend forward. My grandmother smiles at me. I smile back at her. I ask her how it’s going and she shakes her head from side to side.

Do you want to come back home? I say.

I see her mouth trying to move.

Yes? I say.

My grandmother looks at me. I say yes again, slowly, clearly moving my lips. My grandmother looks at my lips. She shapes her own lips copying mine.

Yes, she says.