9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

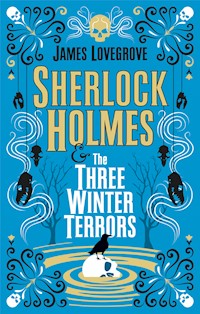

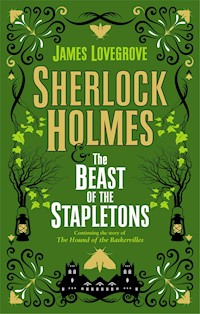

1894. The monstrous Hound of the Baskervilles has been dead for five years, along with its no less monstrous owner, the naturalist Jack Stapleton. Sir Henry Baskerville is living contentedly at Baskerville Hall with his new wife Audrey and their young son Harry. Until, that is, Audrey's lifeless body is found on the moors, drained of blood. It would appear some fiendish creature is once more at large on Dartmoor and has, like its predecessor, targeted the unfortunate Baskerville family.Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson are summoned to Sir Henry's aid, and our heroes must face a marauding beast that is the very stuff of nightmares.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also Available from James Lovegrove and Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Part Two

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Part Three

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

About the Author

ALSO AVAILABLE FROMJAMES LOVEGROVE AND TITAN BOOKS

Sherlock Holmes and the Christmas Demon

The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

The Stuff of Nightmares

Gods of War

The Thinking Engine

The Labyrinth of Death

The Devil’s Dust

The Manifestations of Sherlock Holmes

The Cthulhu Casebooks

Sherlock Holmes and the Shadwell Shadows

Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities

Sherlock Holmes and the Sussex Sea-Devils

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Sherlock Holmes and the Beast of the Stapletons

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781789094695

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789094701

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First hardback edition: October 2020

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© James Lovegrove 2020. All Rights Reserved.

James Lovegrove asserts the moral right to beidentified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is availablefrom the British Library.

This book is respectfully dedicated to

HOLMESIANS AND SHERLOCKIANS EVERYWHERE

in recognition of their passionate admiration and enduring supportfor the deeds of the Great Detective and his ally

FOREWORD

by John H. Watson MD

The friends of Mr Sherlock Holmes – and these days they are many and multifarious – are liable to know well the events that took place on Dartmoor in the autumn of 1889. Such, at least, may be inferred from the reception of my account of the affair, titled The Hound of the Baskervilles, which saw print last year.

Sales of the book were anything but modest – if it is not immodest of me to say so. This and, more importantly, the clamour of critical approbation attending its publication have compelled me now to retrieve my notes on another case, one that occurred almost exactly five years later and upon which Holmes’s earlier investigation had a direct bearing, and turn them into a narrative.

Here, in the pages that follow, you will find the unfortunate Sir Henry Baskerville who, having narrowly avoided death in the prior instance, was again plagued by a lethal, eerie nemesis and obliged to look to Sherlock Holmes as his saviour.

If anything, the episode is even more garish and perturbing than its predecessor, as you shall see. It is with pride and no small amount of caution that I invite you to peruse this chronicle, which I have dubbed The Beast of the Stapletons.

J.H.W., LONDON, 1903

PART ONE

Chapter One

A CANINE CONTRETEMPS

Having finished my rounds for the morning, I decided to pay a visit to my great friend Mr Sherlock Holmes. It was early autumn, with the warmth of summer still lingering in the London air, and the prospect of strolling across Hyde Park on such a clement afternoon to get from Kensington to Baker Street was a highly pleasant one. In that regard, fate had other plans.

Having crossed the Serpentine Bridge, I was proceeding northward along West Carriage Drive, lost in thought. Principally I was musing upon the fact that since Holmes had reappeared in my life a few months earlier, subsequent to that dismal three-year hiatus when I and the rest of the world presumed him dead, my visits to his rooms were becoming ever more frequent. My own home, bereft of the dearly departed Mary and the brightness she had brought to it, seemed increasingly dreary. Every furnishing, every piece of crockery, every curtain and rug reminded me of my late wife, for it was she who had chosen these domestic items. It struck me that reinstating myself in the old accommodation of my bachelor days, sharing once again those well-appointed if rather cramped quarters with Holmes, might be the fillip I needed. I resolved to ask my friend if he would be willing to consider my moving back in.

At that moment, a huge black dog came charging towards me along the path, snarling ferociously.

Sight of the animal filled me with utter, all-consuming dread. I was rooted to the spot, every hair on my head standing on end. The dog was making straight for me, as an arrow flies to its target, and I could do nothing but stare, helpless, unable to move or even think.

Such paralysing terror may perhaps seem strange to my readers unless they recall that not five years prior I had encountered a hound of gigantic proportions upon the moor of Devon, one that caused the deaths of two men and nearly proved the undoing of another. Even though Holmes had killed it stone dead with five shots to its flank, Jack Stapleton’s terrible bloodhound-mastiff cross continued to haunt my dreams. Often I would awaken in bed, soaked in sweat, my heart pounding, having been quite convinced that I was back on fog-shrouded Dartmoor and that the beast was chasing me, its phosphorus-accented features glowing, its fang-filled maw agape and slavering, hell-bent on savaging me to death.

So it was that this dog in Hyde Park seemed like a nightmare come to life, my greatest fear made real. It was hurtling towards me with the clear intent of mauling me. In mere seconds I was going to meet a hideous end.

The dog was less than a couple of yards away, easy leaping distance for so sizeable a creature travelling at so great a speed, when all at once a sharp, shrill whistle resounded from the trees nearby. The dog came skidding to a halt, so close to me now that I could have reached down and petted it, in the unlikely event I should have wished to do so. It stood with its ears erect, its fangs bared, gazing up with dark, acquisitive eyes, regarding me much as it might have a juicy hambone or a cornered rabbit.

“Lucy!” came a gruff voice. “Lucy! Come back here. Lucy! This instant!”

The dog, hearing its name, twitched its head but seemed loath to obey the command.

“Lucy…” said the voice, this time with an unmistakable note of menace.

Now the dog turned about, albeit with a show of great reluctance, as though it could not bear to be drawn away from the human into whose flesh it was so apparently keen to sink its teeth.

A man came into view, brandishing a dog lead. Lucy slouched over to him, aiming the occasional avaricious look back at me. The man grabbed the animal by the scruff of the neck and reattached the lead. Then he strode towards me at a brisk pace, with Lucy trotting at his side.

“Sorry about that,” said this fellow. “Hope she didn’t give you a fright. She’s as meek as a lamb, normally. Just gets a bit excited sometimes.”

My mouth was dry, but I managed to frame words. “A bit excited? The wretched thing was coming to attack me. If you hadn’t called her off, who knows what would have happened!”

“There’s no need to get so hot under the collar about it. You’re all right, aren’t you? She didn’t bite you, did she?”

“Well, yes. I mean, no. Yes, I am all right. No, she didn’t bite me.”

“Then what is the problem?”

Lucy’s owner looked, to all appearances, like a reasonable, respectable gentleman. He was in early middle age and spoke well, and I adjudged him to be some kind of urban professional, a solicitor perhaps or a chartered accountant. He seemed genuinely surprised that I should take offence at his dog’s behaviour.

“The problem,” I said, “is that if your Lucy really is ‘as meek as a lamb’, as you put it, I could not have known that. Certainly not from the way she came at me.”

“You must have acted aggressively towards her. Dogs are known to put on angry displays when somebody threatens or intimidates them.”

“I assure you I did nothing to spark an adverse reaction in her. I was merely minding my own business.”

“You don’t need to do anything,” the man said. “Some people simply give off an aura of hostility towards dogs. That’s all it takes.”

“An aura of…?” I spluttered. My fear was, as if through some process of emotional alchemy, subliming into indignation. “How dare you, sir! It comes to something when a man can’t walk through the park without being assaulted for no good reason by a vicious, undisciplined mongrel.”

“And how dare you!” the other retorted, his voice rising just as mine had. “I’ll have you know that Lucy is a purebred German Shepherd and, what’s more, is as well trained a hound as you could hope to find. You saw how she answered when I called. Like that.” He snapped his fingers.

“Hardly. It wasn’t until the third or fourth time you used her name that she responded. I’ve a good mind to report you to the authorities. What if you had not been around to curb Lucy? And what if I had been not a grown man but a woman, or a child?”

“But I was, and you aren’t,” came the reply, accompanied by an insolent sneer. “So your hypothetical proposition is meaningless.”

“I have friends at Scotland Yard, you know. One word from me and you’d be clapped in irons so fast your head would spin.”

This was an empty threat and we both knew it. Indeed, I felt instantly ashamed to have brought up my police connections, such as they were. Yet Lucy’s owner irked me so greatly that I could not help myself.

“Hah!” he snorted. “Hiding behind the skirts of the law, just because you were scared by a dog. You pathetic, lily-livered weakling.”

“What did you call me? Scoundrel! I’ve seen and done things more hair-raising than an office-bound milksop like you could ever imagine.”

“Milksop, eh? You’ll regret that. I have a boxing blue from Camford.” My antagonist looped the end of Lucy’s lead around the arm of an adjacent bench and began removing his jacket. “It may have been a while ago, but there’s not much about the noble art that I’ve forgotten.”

Tempted as I was to roll up my sleeves and dish out a drubbing to the fellow, or at least give as good as I got, our altercation was drawing a small crowd. To indulge in a public bout of fisticuffs would be unseemly and, worse, liable to result in arrest by a passing constable and charges of affray, which would do little for my standing as a general practitioner. With a deep, self-steadying breath, I elected to be the bigger man.

“I have no wish to get into a brawl over this,” I relented. “Just keep your dog on the lead in future, that’s all I ask.”

So saying, I set off past the man. My blood was still up, and it wasn’t until I emerged from Cumberland Gate into the hurly-burly of Marble Arch that I began to calm down. At that point, I found myself wondering whether the dog really was called Lucy. It seemed altogether too decorous a name for such a brute. Unless, of course, it was short for Lucifer.

I was still chuckling over this little witticism of mine as I crossed the threshold to 221B Baker Street where, it transpired, the beginning of another adventure awaited, one considerably more remarkable and perilous than my canine contretemps in the park.

Chapter Two

BUFFALO SOLDIER

“Ah, Watson!” declared Sherlock Holmes as I entered his rooms. “Your timing could not be more fortuitous.”

“You have a guest,” I said, motioning at the person who occupied the chair opposite Holmes. “Or is it by any chance a client?” I added, hopeful that this was so, for I could think of nothing more appealing than to join my friend on another of his remarkable investigations.

“The latter,” Holmes confirmed.

The stranger rose and offered me a formal bow, which I reciprocated.

“Corporal Benjamin Grier, at your service,” said he, extending a hand. He was a Negro gentleman, large and imposing-looking. Yet, for all that he stood a head taller than me and his shoulders were half as broad again as mine – not to mention that he possessed a voice whose low, rumbling timbre resembled a peal of thunder – there was a marked gentleness and gentility about him. As for his smile, it carried a warmth that could only put one at ease.

All the same, I could not help but notice a certain agitation in Grier’s bearing. This, as far as I was concerned, cemented his status as a client of Holmes’s, for few called upon my friend who were not in need of his services as a consulting detective and thus, for one reason or another, in a state of some anxiety.

“Dr John Watson,” I replied, taking the offered hand. Grier’s grip was powerful, but I sensed restraint in it. He was withholding his full strength and could, so I thought, have crushed every bone in my hand had he wanted.

“It is an honour to meet you, sir. I am a great admirer of your works. I read avidly, Hawthorne and Poe being my favourite authors. You, sir, run them a close third.”

“You are too kind. It is an honour to be numbered in such company, especially since my literary career is still in its infancy. An American?”

“You have me there,” Grier said, letting slip a small laugh. “What gave it away?”

“Watson’s perspicacity is second to none,” Holmes said with an ironical lift of an eyebrow. “Nothing escapes him, least of all a pronounced Yankee accent. Watson, Corporal Grier arrived scarcely two minutes before you. So far I have gleaned a little about him, albeit nothing whatsoever about his reasons for visiting me. He is a soldier, of course. He introduced himself to me by his rank, as he did to you. He is an American, too. That much we have both established. Aside from those two rather obvious inferences, I can hazard a few further.”

“Pray do,” I said, taking a seat.

“If it’s all the same to you, I would prefer that we got down to business, Mr Holmes,” Grier said. “I am here on an errand of some urgency and I feel that every second is crucial.”

“Naturally, Corporal Grier.” Holmes gave an obliging wave of the hand. “Let us delay no further. What, I wonder, has compelled you – a Freemason, who has seen service with the 25th Infantry Regiment during these so-called Indian Wars – to journey to London from the West Country by train, in a forward-facing seat beside the window, and seek me out with some haste?”

Grier’s eyes widened and his jaw dropped. It was a shift in expression familiar to me from the countless other occasions when Holmes would deduce intimate details of someone’s life and habits based upon that person’s appearance alone.

“Very well, Mr Holmes,” said he. “I cannot resist. You have earned yourself a minute of my time to explain how you came by those facts, every one of which is as true as I’m sitting here.”

“A minute will more than suffice. Really all I have done is play the odds, tendering the most likely conjecture in each instance. So often the commonest interpretation of evidence is the correct one. Firstly, an American soldier of your race must perforce belong to one of only four regiments, namely the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry. No regiment in the US army will accept black enlisted men save those four. Collectively, the troops in your regiments are known as Buffalo Soldiers.”

“Yes. The name was given to us by the Apaches. Our skin tone and curly hair remind them, it seems, of a buffalo’s hide and topknot. Even if it is perhaps not meant as a compliment, I choose to take it as one. The buffalo is a mighty, noble beast, docile unless provoked, dangerous when it is. But how can you be so sure I am infantry, not cavalry?”

“Simple. You are far too big to be a cavalryman.”

Grier nodded at that with some amusement. “I pity the horse that would have to carry anyone of my bulk for long distances.”

“That makes you, by default, an infantryman,” Holmes continued, “and hence, given that there are only two foot regiments to decide between, I had an even chance of choosing the right one. Happily, the gamble paid off.”

“Fine, but what prompted you to suggest I am a Freemason?”

“It is a fact – not a well-known one, maybe – that the vast majority of Buffalo Soldiers are also Freemasons. The balance of probabilities that this would be true of you was, therefore, significantly in my favour.”

“You have played your hand excellently,” said Grier, “but I am still mystified as to how you could know I have come here today by train from the West Country.”

“The ticket stub,” said Holmes, gesturing towards the other’s chest. “The one tucked into your breast pocket. Enough of it is projecting for me to discern the words ‘at’, ‘stern’ and ‘way’, from which it is easy to extrapolate the longer words ‘Great’, ‘Western’ and ‘Railway’.”

Grier glanced down at the stub. “The answer was in plain sight all along.”

“The same may be said for proof that you sat in a forward-facing seat. I imagine, with the weather being warm, that it was rather stuffy in the compartment in which you rode and that the window was at least partially open. This would admit smoke from the locomotive’s chimney, and smuts from said smoke have adhered to your left shirt cuff.”

Grier inspected said shirt cuff, observing – as I did – the few tiny dark speckles that besmirched it.

“Compartments on Great Western Railway trains are on the left-hand side of the carriage, with the corridor on the right,” Holmes said. “The location of the smuts thus reveals that you must have been seated facing forward and, moreover, adjacent to the window. It is quite straightforward.” He threw a glance at the mantel clock. “And with that, I believe my allotted minute is up.”

“I will grant you a brief extension to the time so that you can explain how you knew I have come in haste.”

“Oh, as to that,” said Holmes airily, “had your journey been a leisurely one, you would surely have taken the opportunity to neaten yourself up between disembarking from the train at Paddington and making your way to my door. The carelessly neglected ticket stub implies otherwise. So, too, does the rapidity with which you took the stairs to my rooms. Indeed, your general mood is one of impatience and preoccupation. To that end, let us prevaricate no further. How, Corporal Grier, may I be of assistance to you?”

Grier composed himself. “It is not I, Mr Holmes, who require your assistance. At least, not directly. Rather, it is an old friend of mine, a man who is already known to both you and Dr Watson.”

Holmes steepled his fingers and leaned forward. “Go on.”

“The gentleman in question is a Masonic brother of mine. We met in Chicago at the Hesperia Lodge in the mid-eighties, struck up a close comradeship, and have remained in touch ever since, reuniting whenever circumstances allow, although our paths in life have taken us in very different directions. He is Canadian by birth but spent much of his adulthood in America, until providence took him to the shores of your own land some five years ago, where he has remained ever since.”

“A-ha. From that thumbnail description, I believe I can identify the fellow in question.”

“I had a feeling you might. He has told me how you once aided him in his hour of need, when death loomed and all seemed hopeless. Regrettably, sir, a similar evil situation has befallen him again. However, the crisis, I would submit, is far more acute this time than last.”

“I must confess I am in the dark,” I interjected.

“A perennial condition with you, Watson,” Holmes quipped.

“Come now. That is unfair.”

“I apologise. Yet it surprises me, old fellow, that you have failed to interpret the clues Corporal Grier has provided. Can it be that you have forgotten our adventures on Dartmoor back in ’eighty-nine? I know full well that you made copious notes about the case, and by your own admission you have every intention of turning them into one of your published chronicles at some point.”

“My goodness,” I breathed. It seemed an uncanny coincidence that, a mere half hour earlier, I had been forcibly reminded of Stapleton’s grim hound and its predations.

“Yes,” said Holmes. “I see it is all coming back to you.”

“The man I am referring to,” said Grier, “is Henry Baskerville. And I have to tell you, gentlemen,” he went on sombrely, “it is not just Henry’s life that is at stake on this occasion but his very sanity.”

Chapter Three

THE BASKERVILLE CURSE STRIKES AGAIN

“But to begin at the beginning…” said Corporal Benjamin Grier.

“If you wouldn’t mind,” said Holmes.

Sitting back, the American commenced his narrative. “I was owed several weeks’ leave by the army, and got it into my head that I should visit with my old pal Henry all the way across the Atlantic. I was keen to see his home and get an idea of how life as a baronet was treating him. He had a wife now, too.”

“Lady Audrey.”

“That is she. You know her?”

“Know of her. A Devonshire lass, and by all accounts a great beauty.”

“He also had sired a son, and I had yet to make the acquaintance of either. I wrote him, expressing my intentions, with the proviso that if he was too grand now to consort with commoners such as myself, naturally I would not come. In his reply, Henry matched my joshing tone. ‘Normally I send peasants packing with my shotgun when they come to my house, but for you, Benjamin, I shall make an exception.’” Grier heaved a deep sigh. “Those words proved, in the event, to be horribly prophetic.

“Throughout the ocean voyage my prevailing mood was one of joyous anticipation. Everything I knew about Henry’s present circumstances, from the correspondence he and I had exchanged over the years since he came to England, suggested that he had found happiness. He was deeply in love with Audrey, and she had provided him with a healthy heir, name of Harry, who had lately turned three and upon whom Henry clearly doted. He was settling into the ways of Dartmoor, befriending neighbours and enjoying an active social life. It seemed he had put behind him the whole episode involving the hound and Jack Stapleton, or whatever the man’s name was. About this his letters had furnished only a sketchy account, but from what I could gather, it was a horrendous ordeal. By the way, regarding you, Mr Holmes, Henry was fulsome in his praise. The same goes for you, Dr Watson. It is quite apparent that he owes you two his life. But how much can change in a single moment! How easily can disaster strike when least expected!” Grier nodded towards the whisky decanter on the sideboard with an importunate air. “I realise it is barely gone noon, sirs, but might I…?”

I stood up, charged a glass and handed it to him. With appreciation, he drank deep.

“That’s better,” said he, and resumed his account. “Of my arrival at Southampton and my subsequent journey to Devon, there is little to say, other than to mention a strange foreboding that came over me, its intensity increasing the further inland I travelled. At first my inexperienced eye roved with delight over the hills, rivers and quaint villages I passed in a succession of trains. Yet, as I crossed into Devon, the terrain grew not only wilder but in some weird way darker: small towns interspersed with solitary stone hovels, all huddling beneath a low, grey sky. An oppression settled over my spirits, and I ascribed it to the bleakness of my surroundings, and also to exhaustion. I had been a week at sea and am no sailor; nor had my accommodation helped, for all I could afford was a cabin in steerage. There was a part of me, however, that seemed convinced somehow that disaster lay ahead – and in this, alas, it was proved accurate.”

“Yes, yes, enough of the hors d’oeuvres,” said Holmes, somewhat curtly. “Please, I beg you, Grier, the entrée.”

One might deem this remark rude, and I fear his interlocutor took it as such. I, on the other hand, who knew Holmes’s ways intimately, understood that he was excited by Grier’s story and anxious to get to the heart of the matter.

“You are right,” the American said, a little stiffly. “Here I am, insisting that time is of the essence, and what do I go and do but get lost in digression? I shall henceforth do my best to be concise.”

“But at the same time, you must omit no salient fact.”

“Agreed. Well, eventually I alighted at a place called Bartonhighstock, a tiny, out-of-the-way village with an inn and a train halt to its name and not much else.”

I knew Bartonhighstock, for it was there, at a little rural wayside railway station, that I had fetched up, along with Dr James Mortimer and Sir Henry himself, on the way to my memorable sojourn at Baskerville Hall.

“By prior agreement, Henry was to have laid on a wagonette to collect me,” said Grier. “None, though, was to be seen. I waited a full hour, and still no wagonette appeared. This struck me as odd but explicable. Maybe there had been some kind of miscommunication. Maybe Henry had got his dates muddled up, or I had. So I assured myself, even as my misgivings mounted.

“In the end I decided to walk, and duly went to ask for directions to Baskerville Hall. There was no station master – the station was too small for that – but there was a booking clerk. Upon hearing my destination, the fellow’s face turned grim.

“‘You have heard about the recent tragedy there,’ said he. I shan’t attempt to replicate his thick rural burr.

“‘Tragedy?’ I enquired.

“‘The death of Lady Audrey.’

“At that, my heart sank like a stone. All at once, my feelings of foreboding were justified.

“‘Her Ladyship was killed,’ the clerk said, ‘just a short distance from the Hall.’

“‘Killed? How?’

“Now his expression became not just grim but evasive. ‘Well, it’s not for me to say one way or another what might have been responsible. Nobody knows for certain. But a terrible bad death it was. And there are rumours…’

“‘What sort of rumours?’

“‘That some monster did it. Nothing else could account for the awful state of her body.’

“‘Monster,’ I echoed wonderingly. I pressed him for more detail, but none was forthcoming. All he would tell me was that Baskerville Hall was not somewhere I, or anyone, should go. He advised me to take the next train out of Bartonhighstock.

“He still had not vouchsafed the Hall’s whereabouts. However, I managed to extract that morsel of information from him, if nothing else. I can be quite… persuasive when I put my mind to it. What is the good of being built so sturdily if one cannot take advantage of it from time to time?

“I was told it was a distance of some seven miles to the Hall, and it was anything but an easy journey. Yet to a soldier who has marched, day upon day, across desert, mountain and prairie, seven miles is nothing. Having double-checked the route with the booking clerk – for there were many junctions where I would have to make turns, and few signposts for guidance – I hefted my suitcase and set off at a fast lick. A couple of hours of daylight remained, I estimated, and it would not do to get caught out in the open, somewhere remote and uninhabited, as darkness fell.

“Along narrow lanes and up and down hillocky slopes I strode. A wind stirred, bringing enough of a chill to the air that I felt obliged to button my coat up to the neck. The overcast sky darkened. All the while, as I walked, I felt a profound pang of sorrow for my friend Henry. A widower now, after a mere four years of marriage – and his wife taken from him in circumstances which, judging by the clerk’s hints, were as violent as they were mysterious. I recalled Henry saying once, in a letter, that there was a widely held belief that the Baskervilles were cursed. The wicked antics of an ancestor of his, name of Hugo, had seen to it that the family would never know happiness. Successive generations would pay the price for their forebear’s sins. He had mentioned this laughingly, and doubtless when the supposedly spectral hound that killed his uncle was revealed to be no more than a flesh-and-blood dog, it did put Henry’s mind at rest, convincing him that he was not the victim of some supernatural legacy of suffering.

“But now it occurred to me that perhaps, after all, the Baskerville curse was real, and Audrey was just the latest in line to fall to it.

“Night was fast approaching when at long last I spied what could only have been the Hall. As you yourselves know, gentlemen, it is a huge, stark edifice built of black granite and dominated by a pair of twin towers, its walls covered in ivy and inset with meanly small mullioned windows. All Henry had told me about his home was that it was large and rambling, and up until that moment, in my New World ignorance, I had had in my mind’s eye some grand, porticoed mansion in the American style. I had not thought that the place would be quite so ancient, nor quite so austere.

“The Hall sits in a natural depression in the landscape fringed with ragged trees. As I headed downhill towards it, I met a man and a woman coming the other way. He was tall, with a square black beard and a lugubrious air, while she was large and broad and similarly had a very serious look about her. They were carrying luggage, and from their stooped shoulders and repeated backward glances I could see they were in a state of some consternation. I hailed them, and soon enough, after they had overcome their initial wariness, we fell to talking. I swiftly ascertained that these two were the Barrymores, Henry’s butler and housekeeper.”

“The Barrymores?” I said. “They are still working for Sir Henry? That is somewhat surprising, given everything that—”

“Hush, Watson,” Holmes interrupted, wagging an admonitory finger at me. “Let Corporal Grier tell his tale.”

“Mr Barrymore was quick to inform me that he and Mrs Barrymore had handed in their notice that very afternoon and were leaving Baskerville Hall with no intention ever to return. ‘The master’s behaviour,’ he said, ‘has become unconscionable.’

“‘Since Lady Audrey’s death,’ said his wife, ‘he has been quite out of his mind.’

“‘Grief may do that to a man,’ I pointed out.

“‘Grief?’ said Mr Barrymore. ‘Oh, this is not grief, sir. This is something far worse. I would not go so far as to call it madness, but the word is as good a description as any for Sir Henry’s mental state. The fits of rage. The shouting and raving at all hours of day and night. The smashing of plates, the defacing of portraits…’

“‘Nine days we have endured it,’ said Mrs Barrymore, who seemed a woman of some fortitude, if her stolid features were anything to go by. ‘What happened to Her Ladyship shocked us all, but nothing could have prepared us for Sir Henry’s reaction. At the funeral he scarce spoke a word, save for a few combative grunts, and it has only got worse since. This morning he even brandished a gun at my husband! Said he would shoot him, or himself, one or the other, he didn’t much mind. That was the last straw as far as we were concerned. We have quit, and good riddance.’

“‘It is the lad I feel sorry for,’ said Mr Barrymore.

“‘You mean Harry, Sir Henry’s son,’ I said.