Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

A beautifully presented sinister seasonal mystery from the acclaimed author of Sherlock Holmes & The Christmas Demon. 1889. The First Terror. At a boys prep school in the Kent marshes, a pupil is found drowned in a pond. Could this be the fulfilment of a witch's curse from two hundred years earlier? 1890. The Second Terror. A wealthy man dies of a heart attack at his London townhouse. Was he really frightened to death by ghosts? 1894. The Third Terror. A body is discovered at a Surrey country manor, hideously ravaged. Is the culprit a cannibal, as the evidence suggests? These three linked crimes test Sherlock Holmes's deductive powers, and his scepticism about the supernatural, to the limit.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 492

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also Available From James Lovegrove and Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

The First Terror

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

The Second Terror

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

The Third Terror

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

About the Author

ALSO AVAILABLE FROMJAMES LOVEGROVE AND TITAN BOOKS

Sherlock Holmes and the Christmas Demon

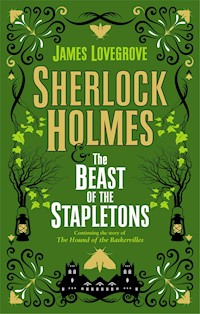

Sherlock Holmes and the Beast of the Stapletons

The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

The Stuff of Nightmares

Gods of War

The Thinking Engine

The Labyrinth of Death

The Devil’s Dust

The Manifestations of Sherlock Holmes

The Cthulhu Casebooks

Sherlock Holmes and the Shadwell Shadows

Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities

Sherlock Holmes and the Sussex Sea-Devils

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Sherlock Holmes and the Three Winter Terrors

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781789096712

Waterstones edition ISBN: 9781789099911

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789096729

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First hardback edition: October 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© James Lovegrove 2021. All Rights Reserved.

James Lovegrove asserts the moral right to be

identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

This book is dedicated to the memory of the late, great

JEREMY BRETT

unquestionably the best onscreen Sherlock Holmes.(Others may disagree, but they are wrong.)

FOREWORD

by John H. Watson, MD

I take up my pen to write again after a lengthy fallow period. There have been too many other demands on my time and attention. First came the late hostilities, during which I renewed my commission as an officer with the Royal Army Medical Corps and worked at the Queen Alexandra Military Hospital at Millbank, treating soldiers afflicted with “Blighty” wounds. The hours were long, and constant exposure to the suffering of those poor, brave injured men took its toll on my energies, so that at the end of each day I had little left in reserve to devote to any other activity.

Following the Armistice, I resumed my duties as a general practitioner, just in time to face the Spanish ’flu pandemic that swept the world during the last year and most of this one. My caseload tripled, and again I was stretched to the point of exhaustion. Readers will be well aware that fully half of London was infected, hospital wards brimmed, and the death toll was appalling, with the mortality rate standing at 2.5%. I myself was laid low by the disease, ending up bedridden for a month and severely debilitated for a number of weeks thereafter, and I am lucky to have survived.

For those concerned as to the welfare of my great friend Mr Sherlock Holmes, he remained ensconced in his farmhouse on the Sussex coast for the duration of the pandemic, having little contact with others, as is his wont these days. Therefore he was spared from exposure and he remains, as ever, in good health.

It is only now, in the winter of 1919, that I feel recovered enough – and once more have sufficient leisure – to set about relating another of the criminal investigations undertaken by the aforesaid Sherlock Holmes. In this instance, it is actually not a single case but three, which took place during the winters of 1889, 1890 and 1894 respectively.

Initially I was uncertain whether I should prepare an account of these episodes for publication, as it entails revealing certain truths that hitherto have not been a matter of public record and casting light upon deeds which the doers might have preferred to remain unilluminated. However, since those directly involved are all now dead, more than one of them a victim of the Spanish ’flu, I feel I need not fear legal repercussions.

Each case, taken on its own merits, is worthy of being chronicled; but, moreover, they share the unique and interesting attribute of together forming what is effectively a single narrative. The common thread is the Agius family – the industrialist Eustace Agius, his wife Faye, and their son Vernon – who happened to find themselves associated with every one of the three incidents.

A second common thread is that the cases all involved phantasmagorical elements and grotesque horrors the nature of which may induce perturbation and even distress in readers of a more sensitive nature. It is not my place to counsel you to be cautious when perusing the pages that follow. Susceptibility to such things varies, and I leave it to your own judgement whether or not you have the appropriate mental fortitude. All I will say is that you may consider yourself warned.

J.H.W., LONDON, 1919

The First Terror

THE WITCH’S CURSE

1889

Chapter One

AN EXTRAORDINARY COINCIDENCE AND AN OLD ACQUAINTANCE

The last thing I was expecting, as Mary and I made our way home after an evening out, was a cry for help.

Until that moment, we had been having a thoroughly pleasant time of it. We had attended a performance of the latest Gilbert and Sullivan operetta, The Gondoliers, which had just opened at the Savoy Theatre. I myself was no great aficionado of the pair’s work – too jaunty and frivolous for my taste – but my wife was and had adored this one in particular. Walking westward down the Strand, huddled together against the cold, I listened as she happily trilled Tessa’s aria “When a Merry Maiden Marries”, or as much of it as she could remember after a single listening. Mary’s singing voice was strong and sweet, and the sound warmed me inwardly, offering a stark contrast to the chill of the night air. London in December is never delightful, and the winter of 1889 was proving a damp and frigid one indeed.

All the passing cabs were taken, but we knew there would be some waiting in the rank outside Charing Cross Station. Before we got there, however, a hoarse, desperate imprecation reached our ears. The cry came from close by, audible to no other pedestrians in the vicinity but us. Its point of origin was an alley leading down to the Victoria Embankment, and Mary and I halted at the entrance to the narrow thoroughfare, exchanging alarmed looks.

The cry was repeated. Somebody, a man, was pleading for succour. “Someone. Anyone! I beg of you. They mean to rob me. Please!”

This was followed by a muttered growl from another man. The words were unclear but the sense was not. They were addressed to the fellow under attack, who was being urged to hush, on pain of punishment.

I looked at Mary again. She saw the need in my eyes.

“There are no police around…” I began.

“Go, John,” she said, disengaging her arm from mine. “I know better than to try to stop you.”

“But I cannot leave you here on the street alone.”

“There are plenty of passers-by. I shall remain in the light of this gas lamp. I shall be safe.”

“But still…”

“Go,” my wife urged me again. “I beg you, though, take care.”

“I shall, you may count on it.”

So saying, I dashed into the alley.

Illumination from the street penetrated barely half a dozen yards into the alley’s darkness. Yet I was just able to make out the figures of three men ahead of me, silhouetted amid the gloom. One of them had his back against the alley wall, cowering. The other two loomed over him in intimidating postures. One of these pair was brandishing a stubby implement, a cudgel of some sort, while his other hand grasped their victim’s shirtfront. From him came the menacing words: “Now then, no more of this snivelling. Your wallet. Hand it over, or it will go hard for you.”

For a fleeting instant I wished I had my service revolver with me. But then, when going out for an evening’s entertainment with one’s wife, one hardly considers it necessary to leave the house armed.

Something I did have on my person that I might employ as a weapon, however, was my walking stick. It was a handsome piece of polished hickory, a gift from Mary on my last birthday, and as I hurried towards the threesome, I hoisted it aloft.

“Halloa, you blackguards!” I said in my loudest, fiercest voice. “Leave him alone!”

All three of them turned their faces to me. In the dim light I could discern that each looked startled by my sudden appearance. The two assailants, however, swiftly recovered their composure. The one who did not have the cudgel moved towards me, bringing up his fists.

I did not break my step. Rather, I increased pace, drawing the walking stick back as I went. The moment I was within range, I swung it at the man. He attempted to ward off the blow with a forearm, but this was a grave miscalculation on his part, failing to take into account both the sturdiness of the implement itself and the considerable momentum behind it. The head of the stick met the point of his elbow with an almighty, jarring crack. If the impact did not break the joint, it was sufficient nonetheless to put the miscreant out of action, for the elbow is a highly sensitive spot, filled with nerve endings. He recoiled away, moaning in distress, arm hanging limp.

His colleague abandoned their victim. “What do we have here?” he sneered, taking the measure of me. “A hero, is it?” He slapped the cudgel into his open palm.

“No hero,” I replied in an even tone. “Merely a concerned citizen. One, I might add, who is holding a weapon with greater reach than yours. You may come at me, sir, but should you do so, you will find yourself as easily incapacitated as your crony was. I suggest you depart at once, you and he both. Or else.”

The fellow gave a show of weighing up my admonition. By this time, my eyes had adjusted to the gloom, and I could see that not only was he tall and brawny, far more so than his accomplice, but he had the look of someone who had known his fair share of physical altercations, at least if his two missing upper incisors and the scar above his left eyebrow were anything to go by. He was not frightened of me, and in light of this, I found that my initial surge of righteous indignation, which had carried me along thus far like a rolling wave, began to abate. In its place came the first stirrings of trepidation. Perhaps I had erred. Perhaps I had allowed gallantry to overcome common sense.

“Ach,” the big man spat, as if in disgust. “It’s not worth it. Come on, you.” He seized his accomplice by the scruff of the neck. “Let’s be gone. There’ll be easier pickings up Soho way, if we play it right.”

So did those two rogues sidle off along the alleyway in the direction of the Thames, disappearing from view and indeed from this narrative altogether, for I never saw them again nor would I learn anything about them other than the obvious, that they were common street thieves. I was left alone with the object of their malicious designs.

The man was leaning against the wall, hunched over, panting hard.

“Are you all right?” I enquired.

“Y-yes,” he stammered. “Yes, I think so. The brutes ill-used me but did not hurt me. God knows what they might have done, though, if you had not happened along. You have my undying gratitude, sir.”

“Think nothing of it. Come, let’s get you out into the street where the light is better, so that I can look you over. I’m a doctor, as it happens.”

“I assure you I am fine,” said the man, but no sooner had he taken a couple of steps than he swooned and, if I had not caught him, would have collapsed.

“You are far from fine,” I told him firmly. “You have suffered a considerable shock. Here, put your arm around my shoulders. That’s it. Now, one foot in front of the other. This way.”

We emerged onto the Strand. Mary’s relief at seeing me safe and sound was palpable. Her brow furrowed in concern as she turned her gaze to the man I was supporting.

“I take it this is the fellow you have rescued, John. How is he?”

“We shall know in a moment.” I helped him sit down on the pavement and tilted his face up so that I could take a good look at him.

It was then that I felt a sudden thrill of recognition.

“By thunder,” I exclaimed. “It can’t be. Can it? Is that you, Rascal?”

The man blinked up at me in astonishment. “Rascal? Nobody has called me that name in years.”

“‘Ragged Rascal’ Wragge. Bless me, it is you!”

“You have me at a disadvantage,” said the other with perplexity. “You know me, but I am afraid I haven’t the faintest idea who you…” He faltered. “Wait. The lady called you John. And now that I think of it, you do look familiar. John… as in John Watson?”

“The very same.”

“Heavens above.” A wan smile appeared on his face. “What an extraordinary thing.”

“Isn’t it?”

“Dearest,” said Mary, “am I to take it that the two of you know each other?”

“At one time we did,” said I in reply, “and indeed very well. But it has been – how long? – twenty years or more since last we were in each other’s presence. Mary, unless I am much mistaken, this is Timothy Wragge, a schoolmate of mine. We were at Saltings House Preparatory together.”

“Good old ‘Whatzat’,” said Wragge. “How nice it is to see you again, after all this time.”

“Would that it were under more auspicious circumstances,” I said. “But we must get you in the warm, Wragge, after your ordeal. A nip of brandy, too, would not go amiss, I’d wager.”

Wragge began to protest feebly, but I would not countenance it.

“Not a word,” I declared. “Do you think you can make it as far as that cab rank?”

“I can try.”

“Good man,” I said, and presently the three of us were snugly ensconced in a brougham and trundling towards Paddington.

Chapter Two

WHATZAT!

I made Wragge comfortable in an armchair in the drawing room. Mary, meanwhile, poured him a brandy, then said she was going to make tea for us. I told her to get the maid to do it, but she pointed out that it was late, the servants were all in bed, and it seemed unreasonable to wake them.

I proceeded to subject my old school friend to a thorough medical examination – eye motion, flexibility of joints, palpating for areas of tenderness. Wragge was, as he had said, unhurt, but he remained badly shaken. It wasn’t until I had plied him with a second glass of brandy that his hands finally ceased to tremble.

“I don’t get up to London much,” he said. “Is it always this dangerous?”

“Only for those who go down alleys where no sane person would venture after dark,” I replied.

“It seemed a useful shortcut.”

“A shortcut to getting your throat cut.”

Wragge looked aghast. “You mean I might have died?”

“No, no,” I hastened to reassure him. “I was exaggerating, for effect. All the same, there’s a good chance those two scoundrels would not have stopped at taking your wallet. I would not be surprised if they had roughed you up further, purely for the fun of it.”

Wragge shuddered. “What a fool I was.”

“Inexperienced, Wragge, that’s all. Not foolish.”

Mary returned with the tea and poured Wragge and me a cup each. “Mr Wragge, you’ll be spending the night with us,” said she. “I will prepare a room for you.”

“I couldn’t possibly impose on you, madam,” came the reply. “When I am recovered, I shall go and find a hotel.”

“I don’t think you understand, Wragge,” I said. “Mary is not asking a question. She is making a statement of fact. You are staying, and there is an end of it.”

Wragge looked set to offer another polite demurral, but then, at a stern glance from Mary, relented. “If it isn’t too much trouble.”

“None at all,” Mary said, and left to make up the bed in the spare room.

“Well, Watson,” said Wragge, “she seems an excellent woman, no doubt about it. Beautiful, too, if I may say so.”

“I am luckier than I deserve.”

“And you yourself seem in good health. You have not changed much. Apart from that moustache and a touch of grey at the temples, I see clearly the John Watson I used to know.”

“The same may be said for you.” Indeed, Wragge retained the fine-boned features I remembered from our early youth, and the intelligent green eyes, not to mention the full, slightly girlish lips. His flaxen hair had thinned somewhat and he had developed a small paunch, but otherwise the years had been kind to him. As schoolboys he and I had not been the closest of friends, but we had shared several interests, including cricket and a fondness for the works of Dumas and Poe, and we had often sat at adjacent desks in class owing to the alphabetical proximity of our surnames.

He glanced about the room. “Generally, you are prospering. Nice house. Loving wife. You are in general practice, then?”

“Since leaving the army, yes.”

“The army. So a man of action as well as a man of medicine. Hence you were not intimidated by those two louts.”

“I wouldn’t say I was not intimidated, but I have faced a fair few villains in my time. When my blood is up, I refuse to be cowed.”

“How fortunate for me that that is the case. It’s funny, though. I always thought you would become a writer. As I recall, you were constantly scribbling down stories in notebooks in the dormitory before lights out.”

“It so happens I have had a book published, just the year before last.”

“You don’t say!”

“Yes, and it met with some success.”

“My congratulations. I apologise for not knowing that, but then, living where I do, I am rather out of touch.”

“And where is that?”

Wragge gave a soft chuckle. “You may not believe this, but Saltings House.”

“You are employed at the school?”

“I have been a master there these past five years, teaching Latin, Greek and Ancient History, as well as a bit of cricket coaching. Before that, I had a position up in Yorkshire at a place called the Priory School.”

“A schoolmaster,” I said. “Yes, I can see how that might suit you, Wragge. You were always far more studious than I. But the school holidays do not start for another week. What, pray, has brought you up to town on a weekday during term time? It must be some urgent errand.”

“Very urgent.” Wragge’s expression clouded. “One, indeed, that requires the involvement of Scotland Yard, no less.”

“Were you intending to visit the Yard tonight? The hour is far too late for that. I doubt you would find more than a couple of constables on duty, and certainly no inspectors.”

“I planned to stop by there first thing in the morning,” said Wragge. “I was unable to get away from Saltings House until late, you see. I had to oversee evening prep, and then lights out in the dormitories. Once I had discharged those duties, I caught the last train up to London. My intention was to find myself a hotel for the night, as near to the Yard as possible so that I could call there early and be back at school in time for first lesson. It was while I was seeking said hotel that those two men waylaid me.”

“Ah. And this matter cannot be dealt with by your local constabulary?”

“I think not. The business is more serious than that.”

“Goodness me. Well, would you care to expound?”

At the back of my mind, a thought was forming. I knew of someone whose services one might engage when it came to investigating “serious business”, and whose powers of deduction and analysis were infinitely superior to those of any policeman.

“I cannot see the harm, I suppose,” said Wragge. “It so happens there has been a death at the school.”

“Heavens,” I declared.

“Yes. A death in suspicious circumstances. Just last week, one of the pupils was found drowned in the lake. Only thirteen, in his final year.”

“How awful.”

“Quite,” said Wragge, with feeling. “Mr Gormley – that’s the headmaster – insists it was nothing other than a tragic accident. I, however, have my doubts.”

“Tell me more,” I said, then amended, “Actually, don’t. I have a better idea.”

“What’s that?”

“Wragge, I don’t suppose you’ve heard of a fellow called Sherlock Holmes.”

He frowned. “The name doesn’t ring a bell. Should I have?”

At that time, Holmes’s career as a consulting detective was almost a decade old, but his fame had yet to spread much beyond the limits of London, and even then was largely restricted to certain social circles within the capital and of course, in a different way, to the criminal underworld. My accounts of his exploits would do much to bolster his reputation both nationally and internationally, but as yet, only the first of them, A Study in Scarlet, had appeared in print.

“It does not matter,” I said. “What matters is that, if you have a problem of an abstruse or delicate nature, Sherlock Holmes is your man. You would be far better seeing him about it than anyone at the Yard.”

“Are you sure?”

“Quite sure. I will take you to him first thing tomorrow.”

Having shown Wragge to the spare room, I retired to bed. Mary had waited up for me, and enquired after Wragge’s wellbeing. I recounted our conversation, and she agreed that, if Wragge felt there was something amiss with regard to the drowned pupil, it was worthwhile bringing Holmes in on it.

“Mr Holmes will prove him right,” she said, “or he will be able to allay his misgivings. In either case, it will bring him satisfaction.”

“My thinking precisely.”

“One question, dear.” She gave a quizzical smile. “‘Whatzat’?”

“Oh, you know how schoolboys are, Mary,” I said, with a small blush. “You only have to do something once to earn a nickname, and then you’re stuck with it until you leave. In my case, I used to get rather enthusiastic when calling a batsman out during cricket matches, and one day I accidentally yelled ‘whatzat’ instead of ‘howzat’. Because it sounded a bit like my actual name, everyone started calling me that instead. It’s a little embarrassing.”

“No, it isn’t,” Mary said. “It’s sweet. Now turn out the lamp and get some sleep, John. I rather suspect that ‘Whatzat’ Watson and ‘Ragged Rascal’ Wragge have a busy day ahead of them.”

Chapter Three

THE MARK OF THE SEASONED ACADEMIC

As Wragge and I walked to Baker Street the next morning, he enquired tentatively whether this “consulting detective” friend of mine was a professional and, if so, was he expensive.

“A teacher’s salary is modest,” said he. “I have little to spare, and everything costs more in London.”

“Do not give it a second thought,” I said. “Holmes often renders his services for free, if he feels the cause is worthy and the case interesting enough. Even if that does not happen in this instance, I shall enjoin him to give you a preferential rate. Failing that, I will pay his fee myself.”

“You would do that for me?”

“What are old school friends for?”

Upon entry into Holmes’s rooms, I could tell straight away that my friend was absorbed in some thorny conundrum. Newspapers, reference books and notes jotted on scraps of paper littered the floor, while the atmosphere was thick with pipe smoke. Holmes himself was seated in his favourite chair with his knees drawn up and that faraway look in his keen grey eyes that betokened deep thought. I daresay he had been up all night, pondering.

“Watson,” he said, the vaguest of greetings. “Forgive me, but I cannot speak to you right this moment. I am awaiting a telegram from my brother that will determine whether my hypothesis about a rather important case is correct or not. You and the gentleman with you make yourselves at home. You know where the tobacco is. It shouldn’t be too long.”

Wragge and I did as bidden, and for a while we all sat in silence, the only sounds the clatter of carriage wheels and horse hooves on the cobbles outside, the sonorous tick of the mantel clock, and the occasional tap of pipe bowl on ashtray.

Then the doorbell rang and a messenger came up with the anticipated telegram. Holmes scanned the slip of paper, whereupon a smile tweaked the corners of his mouth. He penned a reply, and the boy took this and his payment and scurried off.

Holmes then passed the telegram to me. “Take a look at that, old fellow.”

The message was brief, comprising a mere three words:

NO SHIP SHERLOCK

“What do you make of it?”

“What am I expected to make of it?” I said. “Without context, the sentence is meaningless.”

“Ah yes. I imagine you have not been keeping up with events in the Farthingale affair. Well, there is no reason you should have, I suppose.”

“You are referring to the steam clipper Farthingale, which sank in heavy seas in the Bay of Biscay last month, with the loss of all hands. I read about it in the papers. It was just another terrible maritime disaster, was it not?”

“There is a little more to it than that,” said Holmes. “The Farthingale was carrying valuable cargo – gold bullion – and doubts have been raised at Lloyd’s of London as to whether she sank at all.”

“You mean insurance fraud could be involved?”

“That and more. Mycroft tasked me with finding out the truth, on behalf of several Lloyd’s Names who are intimates of his. As a result of my investigations, I was able to ascertain that everything hinged upon the existence, or otherwise, of a clipper by the name of Nightingale that is more or less identical to the Farthingale. Now, the harbourmaster at Bilbao, on the north coast of Spain, stated that a ship called the Nightingale entered his port on the fourteenth of November. That is the day before the Farthingale is alleged to have sunk.”

“Could the Nightingale have been the Farthingale, refitted and given a slightly different name?”

“Just so, and in that case, it is likely there was misconduct. The cargo of bullion had already been unloaded elsewhere, doubtless to be fenced through some criminal network, and then the Farthingale, rather than being scuppered, was repurposed as a ‘new’ ship and an insurance claim lodged.”

“Two thefts for the price of one.”

“Ha! Very droll, Watson, but also quite correct. I asked Mycroft to confirm, via his extensive network of sources, whether a Nightingale did put in at Bilbao on that date.”

“And by ‘No ship Sherlock’ he is stating, in typically terse manner, that she did not.”

“She did not,” said Holmes with a shrug. “There is, in fact, no such vessel. It was the Farthingale all along. The Spanish harbourmaster simply confused the words Nightingale and Farthingale, and wrote down the former when he meant the latter. An easy mistake to make if English is not your first language. The Farthingale did then go down the next day, as was believed all along, and therefore Lloyd’s must pay out. It was not too tricky a mystery to solve, but it required thought and patience. Now then, to what do I owe the honour of this visit? I can only assume that our friend here – a schoolmaster from rural Kent, if I do not miss my guess – has need of me.”

I looked at Wragge, fully expecting to see astonishment writ large upon his face. This was the customary reaction whenever Sherlock Holmes made one of his detailed, accurate deductions about a person’s circumstances based on physical appearance alone.

Wragge, however, evinced little in the way of surprise.

“Aren’t you curious as to how Holmes knows what you do for a living and where you live, Wragge?” I said, feeling somewhat crestfallen. I had been hoping that the display of my friend’s talents would impress him.

“Oh,” said Wragge. “I presumed you wired Mr Holmes late last night, in advance of this meeting, and informed him about me. You mean to say you didn’t?”

“No.”

Wragge canted his head to one side, pursing his lips. “Well then, that is deuced clever of you, Mr Holmes, I must admit.”

“A mere trifle,” said Holmes, with a dismissive wave of the hand.

“How are you able to draw these inferences about me?”

“The rural part of it is easy. Your jacket is made of green houndstooth tweed, a fabric rarely if ever worn in the city. It is, moreover, cut in a style which is no longer fashionable in the capital – those narrow lapels, that double buttonhole – but which persists in the country. Furthermore, the uppers of your shoes bear traces of mud that is too pale to have come from London’s streets.”

“Fair enough,” said Wragge. “My clothing betrays me. But how did you know I am from Kent specifically?”

“You have a copy of volume one of Bradshaw’s in your pocket,” said Holmes. “The title is just visible, peeking out. That section of the railway handbook covers London and its immediate environs, from Kent to Devon, with the Isle of Wight and the Channel Islands thrown in. The pale mud I referred to a moment ago is the type known as London Clay and, outside the capital, is found primarily in the marshlands of the Thames and Medway estuaries in northern Kent.”

“But could it not have adhered to my shoes since I arrived in London, not before?”

“The alluvial deposits of London Clay in London itself are deep-seated. The city has been built over them and they are visible solely on the bed of the river when the tide is out. The mud on London’s streets is of a quite different composition. Ergo, unless you have been trudging along the Thames foreshore, which I doubt, you came by your mud stains elsewhere.”

“Very well.” Wragge seemed satisfied with Holmes’s elucidation. “But what about the schoolmaster part?”

“You have a certain way about you,” Holmes replied, “an air which I can only describe as professorial. A slight stoop, a way of peering. It is almost invariably the mark of the seasoned academic. Add to that the light powdering of chalk dust upon your right sleeve, doubtless gained from resting your arm against a blackboard as you write on it, and the supposition becomes a certainty.”

“All of that might mean I was a university lecturer, though, just as easily as it might mean I was a schoolmaster.”

“True. However, you appear in reasonably good physical condition, and the great majority of university lecturers are not. They shun exercise and the outdoors. Schoolmasters, on the other hand, are often required to be outside, coaching their pupils in various sporting endeavours.”

Wragge leaned back. “You are insightful indeed, sir. Watson speaks highly of your prowess, and with some justification, it would seem.”

It was time for me to make formal introductions. “This, Holmes, is Timothy Wragge, a contemporary of mine at prep school, who now teaches there.”

“Saltings House, eh?” said Holmes. “Then, Mr Wragge, I can only assume you have come to see me regarding the death of one Hector Robinson, a pupil in your charge.”

Wragge’s eyebrows shot up. “How can you know that?” He turned to me, a mistrustful expression stealing over him. “Are you sure you did not contact Mr Holmes last night, Watson?”

“You think this is a ploy he and I have concocted between us?” I said. “Some kind of trick?”

“It has crossed my mind.”

“To what end?”

“To win me over and ensure my custom.”

I was somewhat offended. Wragge was impugning my honour, and Holmes’s. Yet his suspicions were, I supposed, forgivable, and I reined in my indignation.

“Really, Wragge,” I assured him, “it is no trick. Did you tell me that the boy was called Hector Robinson?”

“Come to think of it, I did not.”

“No, you didn’t. So I could hardly have imparted that information to Holmes, then, could I? That said, Holmes, it is my turn to be mystified. How did you know the boy’s name?”

“Nothing to it,” said Holmes. “As you can see from the state of the floor around me, I read the newspapers. A lot of newspapers. I subscribe not only to the national dailies but to many of the regional organs as well, not least those hailing from the immediate environs of London. One such is The Kentish Gleaner, in whose pages it was reported that a boy, name of Hector Robinson, met his death by drowning at Saltings House School the Tuesday before last. I have the sort of mind that is apt to retain data, not least those pertaining to the more morbid aspects of life. It is a prerequisite for one in my vocation. My mind is yet more apt to retain a particular datum if it has a connection, however thin, to my dearest friend in the world – if, for instance, it pertains to a school where he spent several of his formative years. In point of fact, Watson, I was going to draw your attention to the Gleaner article when next we met, if purely as a curiosity. It would appear fate has closed that circle in a different fashion. Mr Wragge, young Robinson’s drowning is believed to have been death by misadventure. Such is the view of the local police and also of your headmaster, as quoted in the paper. You would not be here, however, if you did not disagree.”

“Indeed so, Mr Holmes.”

“Then, sir,” said Holmes, placing his palms together and adopting an attitude of great attentiveness, “I would be obliged if you would regale me with the facts of the matter.”

Chapter Four

THE FACTS OF THE MATTER

“Hector Robinson,” Wragge began, “was not what you might call popular at Saltings House.” He leaned forward in his seat a little nervously, resting his elbows on the arms and interlacing his fingers. “Rather, he was one of those boys who seem to rub people up the wrong way. His peers tended to dislike him. The majority of the teachers were unimpressed with his scholastic achievements, which were average at best. He was sallow-skinned and sickly looking – hardly resembling the Greek hero with whom he shared a name – and he exhibited a kind of surly diffidence that was deeply unappealing. It isn’t that he was mean-spirited in any way, or deliberately gave offence. There was nevertheless something offensive about him.”

“Some people are like that,” said Holmes. “They have the misfortune to radiate disagreeability, like a bad odour.”

“I try to see the best in all my pupils, but with Robinson I cannot deny I struggled. Harsh as it may sound, the lad had few redeeming qualities. It may not surprise you to learn that he was unhappy at Saltings House; nor that, given his character, his unhappiness was compounded by being the object of bullying. Now, of course, bullying is commonplace at all schools…”

“Indeed,” I said. “As I recall, we ourselves were rather mean to several of our contemporaries, weren’t we? Percy Phelps, for instance. Remember him? ‘Tadpole’ Phelps. We used to chevy him all the time. It did him no lasting harm, though. He went on to Cambridge and then the Foreign Office, where he has had a glittering career.”

The last part was not entirely true. I refrained from mentioning that, earlier in the year, Holmes and I had come to Phelps’s aid when an important naval treaty went missing from under his nose. I would later publish an account of this exploit, but at the time the theft and recovery of the document remained a state secret and I was bound by confidentiality laws from discussing it.

“Phelps had a brilliant mind and great reserves of self-assurance,” said Wragge. “He could cope. Not so Hector Robinson. Moreover, the treatment Robinson received was unduly vicious. Two boys in particular, Jeremy Pugh and Hosea Wyatt, took it upon themselves to persecute him relentlessly, finding all manner of ways to torment him. Sometimes it would simply be tripping him up as he walked or giving him an unexpected cuff round the ear. Other times it would be humiliation, such as emptying an inkwell over him, tipping his lunch into his lap or slipping a dead mouse between his bedcovers. Then there was the verbal abuse, subtler but no less insidious. Name-calling. Making insinuations about his parents. Accusing him of deviant behaviour. Whenever I witnessed it personally, I did what I could to curb it, but I cannot control what goes on when I am not present. Besides, Pugh is a great all-rounder, both academically and on the sporting field, and is currently Head Boy. Big things are expected of him in the future. As for the Honourable Hosea Wyatt, he is somewhat less gifted, but his father is Lord Gilhampton, the Member of Parliament for Woking and a senior Minister of the Crown. Both lads are the apples of Headmaster Gormley’s eye and can do no wrong in his book, so whatever complaints I made to him about their mistreatment of Robinson were met with stony indifference.”

“Everything you have said so far might lead one to the conclusion that Robinson’s drowning was self-inflicted,” said Holmes. “He had been made miserable by the attentions of these two bullies, becoming so downcast that he saw no alternative but to take his own life.”

“I agree. You can imagine it, can’t you? Day in, day out, a constant scratch, scratch, scratch of cruelty, eroding his confidence, undermining his sense of his own worth. It could easily have driven him to suicide.”

“But you still think not.”

“I would not put it beyond Pugh and Wyatt to have dragged Robinson out to the lake, forced him into the water and held him under. It may not have been their intention to kill him. Perhaps they meant it as a prank and things got out of hand.”

“Manslaughter, not murder.”

“That does not make them any less culpable, as far as I’m concerned.”

“You have no proof of this, though.”

“None whatsoever. Just a strong instinct that Robinson did not kill himself and that his death was not a mishap either.”

“Very well,” said Holmes. I could see that, as yet, he was far from convinced there was a mystery to be solved here. “It would help if you could tell me a little more about the actual circumstances of his drowning. All I know from the newspaper, whose report was rather skimpy on detail, is that the lad was found floating face down in the school lake.”

“I was not there when the body was recovered from the water.”

“Who did find it?”

“The groundskeeper, Talbot.”

“Not ‘God’ Talbot!” I ejaculated. “Is he still there? He must be a hundred years old by now.”

“Still there, and still as cantankerous as he was when we were boys,” said Wragge. “Still as fond of a drink, too.”

“He was known as ‘God’,” I explained to Holmes, “because he had a bad leg and––”

“And therefore moved in a mysterious way,” Holmes finished for me, his tone impatient. “Yes, yes, I get it. Very witty. Now, if we may confine ourselves to the case and leave these schooldays reminiscences of yours for another time… Thank you. Go on, Mr Wragge.”

“Attempts were made to revive Robinson, so I am told,” said Wragge. “The school matron, Mrs Harries, employed a kind of resuscitation technique, pressing repeatedly on his stomach, but to no avail. He was clearly dead and had been so some while. Mr Gormley, who arrived on the scene not long after Mrs Harries had abandoned her efforts, immediately pronounced that Robinson had drowned by accident. ‘The boy went swimming,’ he said, ‘got into difficulties, and perished. It was his own fault.’ But I ask you, gentlemen, who in his right mind would go swimming in a lake before dawn on a December morning when the water was freezing cold? Gormley’s contention is preposterous.”

“You say ‘in his right mind’,” said Holmes, “but it is conceivable that a youngster whose life was being made a living hell by his tormentors would be anything but in his right mind.”

“Granted, but you should have seen Pugh and Wyatt, Mr Holmes, when the tragedy was announced by Mr Gormley at assembly that morning. I was watching them, looking for a reaction, and they were dismayed and horrified. Their behaviour since has, I admit, been much the same as usual, but in that moment, I saw it on their faces. I swear I did. Guilt.”

“Guilt, or simply the bully’s remorse, which he is wont to suffer when events bring home to him the full import of his actions. Robinson drowned himself, and Pugh and Wyatt realised they had driven him to it through their hounding and harassment, and were suitably chastened. In that case, they are not answerable in a court of law for the outcome of their transgressions, although one hopes that a higher power will hold them to account for it in the life hereafter.”

“But what if they did actively kill him?”

“Then that is a very different story.”

“And if Watson is to be believed, you are the man to prove it,” said Wragge earnestly. “You must understand, Mr Holmes, the entire school is in a ferment right now.”

“With good reason. An awful thing has happened.”

“No, I mean that the atmosphere at the place is poisonous. The boys are recalcitrant and refractory. They cannot concentrate on their studies. At times they are downright mutinous, and no amount of disciplining by members of staff will bring them back into line. It is all to do with the witch’s curse, you see.”

“Gracious,” I interjected. “Of course. I had forgotten all about that.”

Holmes leaned back in his chair. “The witch’s curse,” he echoed sardonically. “Whatever can that be, eh?”

“It is a legend,” said Wragge, “dating back to the school’s founding and beyond.”

“But you are probably not interested in hearing about it, Holmes,” I said. My tone was, I will admit, somewhat peevish. “After all, you are so contemptuous of these ‘schooldays reminiscences’ of ours.”

“Oh, Watson,” said my friend, feigning contrition. “I’m sorry if I hurt your feelings earlier. I should very much like to know about this curse and what bearing, if any, it has on Hector Robinson’s death.”

“I must warn you,” I said to Wragge, “Holmes has no truck with the paranormal. He reserves his deepest scorn for anything that carries even the faintest whiff of ghosts, magic or the unearthly.”

“To the rigorously logical brain,” Holmes said, “such things are anathema.”

“I share that view,” said Wragge, “to a degree. There is no question, however, that drownings have been a recurring theme at Saltings House, or rather on the land Saltings House is built on, and it all relates to a witch called Old Sarah.”

Chapter Five

THE TERRIBLE TALE OF OLD SARAH

At this point, Mrs Hudson appeared with a pot of coffee on a tray.

“I had a feeling you might be after a pick-me-up, Mr Holmes,” said that good lady. “I have made enough for Dr Watson too, and your guest.”

“Your prescience borders on the uncanny, Mrs Hudson,” said Holmes. “I was just on the point of calling down for coffee, and here you are, anticipating my wishes. Are you certain you are not clairvoyant, madam? A witch, even?”

He framed the query teasingly, and Mrs Hudson took it in that spirit, albeit with some puzzlement. “If by clairvoyant you mean sensitive to the needs of others,” she replied, “then that is true of almost all women, and regrettably few men. I also know when my lodger has been up all night, working, and could do with a morning restorative.”

She poured us each a cup and left.

“Now then, Mr Wragge,” said Holmes, taking an appreciative sip, “tell me about Sarah the witch. I am in the mood for something that tingles the spine.”

I gave Wragge a look, hoping to convey apology for Holmes’s facetiousness.

Wragge merely shrugged and said, “Back in the early seventeenth century, at the height of the witch-hunt mania that seized this country and most of Europe, a coven was unearthed in the north Kent countryside. Five women were accused of practising black magic, consorting with imps and demons, holding blasphemous midnight rituals and the like – everything short of riding broomsticks through the air. They were arrested by constables and held at the county assizes in Gravesend until a witch-finder could be found to verify the truth. It so happened that one lived close by, a local squire by the name of William Chapman, a devout Puritan with a particular passion for seeking out and executing witches. He wasted no time in subjecting the five to so-called trials in order to get them to confess. This entailed various forms of torture that were standard in most witch-hunts. The women were refused food and water and kept awake for hours on end until they were so exhausted their thoughts became addled and they did not know what they were saying. They were cut with blunt knives, and when they did not bleed, this was deemed proof of unholy powers. They were stripped bare and their bodies searched for the ‘Devil’s mark’, a birthmark, perhaps, or a mole, the presence of which was conclusive evidence that Satan was their lord and master.”

“Hardly empirical methods, any of those,” said Holmes.

“Well, quite. Methods designed, rather, to bewilder, hurt and demean, until the alleged offenders became so cowed and wretched that they would admit to anything, simply to make it stop. Then came the drownings. The five witches – they were inarguably that now, for each had signed a confession admitting her guilt – were taken to Saltings. That’s the name of the area of marshland where the school is sited and where, furthermore, Chapman had his manor house. There, they were dragged to one of the inlets that leads to the Thames estuary, and one after another they were thrown into the water with their thumbs tied together and their big toes likewise. This was the final test of their witchy powers. If they bobbed to the surface and swam, plainly the Devil was helping them, and as a result they would be hauled back out and hanged. And if they sank…”

“They drowned, and the point was moot.”

“The supposed head of the coven was called Sarah. Her surname is lost to the mists of time, and she was known to all in the area just as Old Sarah. She was the most senior among the five and had served for decades as a midwife and a healer in the region. Chapman decided she must be the ringleader because she had been the least cooperative. That is to say, she held out the longest under torture before breaking. The night before she was subjected to the water test, a priest visited the room where she was being held, in order to bring her the comfort of the scriptures. Sarah remained defiant. She told the priest that her confession to Chapman was invalid because it had been made under duress. It was a position she maintained right to the end.”

“And she was not wrong to do so.”

“She claimed that she and the others were the victims of malicious gossip. They were friends who enjoyed a spirited get-together from time to time, and there was no harm in that. But women who convened in the company of their own sex exclusively were, it seemed, not to be trusted. They must be up to no good, and the likeliest explanation was that they were witches. You need to bear in mind that the country was in upheaval in the wake of the Reformation. There was a collective moral panic, and people were looking for a scapegoat, something to blame for the nation’s ills. They decided the answer was witchcraft, and soon everyone was seeing witches everywhere. If a woman did not behave as a woman ought, if she showed a spark of unconventionality or rebelliousness, then there could be only one cause for it: she was in league with Lucifer.”

“You seem well-versed in the topic, Mr Wragge,” Holmes observed.

“I read up about the Saltings witch trials not so long ago. I teach Ancient History, but history in general is a subject for which I have a real passion, and shortly after I took up my post at the school, I recalled the legend and felt moved to do some research. Old Sarah, at any rate, was the last of the five to be thrown into the water. What happened to the other four is not recorded, at least not in any of the local archives I consulted. My assumption is that they did not rise to the surface.”

“Or did, but Chapman had no interest in rescuing them. He simply left them to drown.”

“Yes. Otherwise they would have been pulled from the water and undergone formal execution, and there would be some official documentation of that. As I was saying, Old Sarah was the last of them, and just as she was about to be flung into the inlet, she addressed the assembled company. She denied any wrongdoing, called William Chapman a fraud and a monster, and she said that if she did have a witch’s powers, she would use them now to call down a curse upon his head. She would beg the Devil to ensure that Chapman met with the same fate that she was about to suffer. One can only imagine the reception this got.”

“Chapman, I should think, professed himself impervious,” I said, “being convinced that he had God on his side and that his faith would protect him.”

“I should think so too,” said Wragge. “And then Old Sarah joined her fellow ‘witches’ in the water, and doubtless like them strove her hardest to stay alive but, hobbled as she was, could not for long. Meanwhile, Chapman and the others in the small crowd that had gathered to watch the proceedings looked on from the shore, perhaps congratulating themselves on ridding the world of an evil.”

“And what became of Chapman in the end?” said Holmes.

“That’s the thing, Mr Holmes. Not a year later, what should happen but that he did drown, just as Old Sarah had wished for, and, what’s more, in that selfsame stretch of water. He was out in a rowing boat with his family. It was clement weather, and yet, for no apparent reason, the boat capsized. Chapman’s wife and two sons made it safely to shore, aided by some of the locals. He himself did not. His body was recovered the next day.”

“Poetic justice,” my friend averred.

“And an ironic end to the story,” said Wragge. “Or it would have been, had not two subsequent owners of Chapman’s house died in a similar manner. One was a privateer, John Markby, who plundered foreign ships in the Caribbean on behalf of Queen Anne. The other was an admiral, Hatherthwaite, who had served at Trafalgar under Nelson and was in charge of the naval dockyard at Chatham. Both perished at sea.”

“Statistically speaking, that is not an unlikely demise for a man in the nautical profession.”

Wragge acknowledged the remark with a nod of the head. “Regardless, it came to be believed that not only had Old Sarah’s final words incited dark forces to weigh against William Chapman, but her curse had somehow infected his home too, so that anyone who lived there was liable to die just as he had. In consequence, the manor house came to be shunned. It was tendered for sale but nobody would buy it, and gradually it fell into rack and ruin and had to be demolished. Sometime around the turn of the century, a new house was built on the land, and this, in due course, became Saltings House School.”

I cut in. “The man who built the new house – his name currently escapes me – was aware of the curse of Old Sarah and took steps to mitigate its effects. He had a priest bless the grounds, and he erected a memorial to Old Sarah as well, an obelisk with her name carved on it.”

“That’s right,” said Wragge. “He was a shipping magnate, name of Obadiah Jackson, and the obelisk has come to be known as Old Sarah’s Needle. Jackson’s son Quentin sold the property in order to pay the death duties on his father’s estate, and that was when it was turned into a school. Old Sarah’s Needle is still there, and has been regarded with a kind of superstitious awe by generation after generation of Saltings House pupils. According to schoolboy lore, on Halloween night the ghost of Old Sarah emerges from the marshes, crosses the school grounds and vanishes into the obelisk, cackling to herself all the while. As she goes by, her feet squelch, and she leaves a trail of sodden grass behind her.”

“Yes, that was the story, wasn’t it?” I mimed a shudder, but it was not wholly an act. How well I recalled being told about Old Sarah’s ghost by a senior boy, our dormitory captain, on one of my first nights at Saltings House. I scarcely slept a wink that night, and when October 31st came round and we went to bed, I huddled under the covers with my hands pressed to my ears so that I might not hear those damp footfalls on the lawn outside and that dread cackling. I was only eight, but my terror was pure and genuine; and so indelibly was this terror imprinted in my psyche that I felt it again now, an echo of it at least, as I cast my mind back.

“No one knows who first dreamed up the yarn, but it persists still,” said Wragge. “Many’s the boy in my charge who has come up to me and jabbered on about Old Sarah’s ghost, having himself learned of it for the first time. Many’s the boy, too, who will not go near Old Sarah’s Needle, not even in broad daylight, such is the hold her legend has over the school.”

“Obadiah Jackson did not die of drowning, I trust,” said Holmes.

“No. He died in bed. It was cancer that carried him off.”

Holmes gave a mordant chuckle. “Then his act of propitiation worked, and its influence has held fast.”

“So it would seem.”

“Until now, that is.”

“Mr Holmes,” said Wragge, rising to his feet. He began pacing back and forth on the bearskin hearthrug. “I fully understand your scepticism. I am not asking you to believe that Saltings House labours under a curse from a long-dead witch. What I am trying to do is explain why the mood at the school is so febrile at present. You have a hundred and fifty boys aged eight to thirteen, every one of whom knows about Old Sarah, knows that witches were drowned close by the school some two and a half centuries ago, has been reliably informed by their peers that the ghost of one of these women habitually haunts the place, and is altogether so impressionable that he regards these fancies as fact.” He stopped pacing long enough to run an anxious hand through his thinning hair, then started again. “Then what should happen but one of their number drowns. Appalling as that event is, it is made all the more appalling by the supernatural connotations it evokes. The pupils, almost without exception, are convinced that Old Sarah’s curse has struck once again, and are in a state of heightened tension. When they are not being mulish, they are having tantrums, and when they are not having tantrums, they are breaking down in tears. This has been going on for over a week, and has risen to such a pitch that it is now little short of hysteria. Mr Gormley has been trying to keep a lid on things, but his approach to governance revolves around the repeated application of the cane. I am not against corporal punishment – ‘spare the rod, spoil the child’ and all that – but it can often have the effect of making a situation worse, not better, especially if used to excess.”

“The more you beat them, the more it compounds their agitation.”