9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

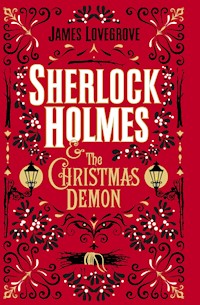

The new Sherlock Holmes novel from the New York Times bestselling author of The Age of Odin.It is 1890, and in the days before Christmas Sherlock Holmes and Dr John Watson are visited at Baker Street by a new client. Eve Allerthorpe - eldest daughter of a grand but somewhat eccentric Yorkshire-based dynasty - is greatly distressed, as she believes she is being haunted by a demonic Christmas spirit.Her late mother told her terrifying tales of the sinister Black Thurrick, and Eve is sure that she has seen the creature from her bedroom window. What is more, she has begun to receive mysterious parcels of birch twigs, the Black Thurrick's calling card...Eve stands to inherit a fortune if she is sound in mind, but it seems that something - or someone - is threatening her sanity. Holmes and Watson travel to the Allerthorpe family seat at Fellscar Keep to investigate, but soon discover that there is more to the case than at first appeared. There is another spirit haunting the family, and when a member of the household is found dead, the companions realise that no one is beyond suspicion.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 395

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also Available from James Lovegrove and Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One: A Felonious Father Christmas

Chapter Two: The Allerthorpes of Fellscar Keep

Chapter Three: The Black Thurrick

Chapter Four: An Archetypal Petrarchan Sonnet

Chapter Five: Fellscar Keep

Chapter Six: Dinnertime Purdah

Chapter Seven: A Marvellous Medium

Chapter Eight: The Monolith In the Glade

Chapter Nine: Shadrach Allerthorpe’S Brief But Most Curious Narrative

Chapter Ten: Ice And Soil

Chapter Eleven: An Additional Benefit of Domestic Retainers

Chapter Twelve: The Smell Of Melancholy

Chapter Thirteen: The Gathering of the Clan

Chapter Fourteen: My Long Night of Penance

Chapter Fifteen: Leaping to a Conclusion

Chapter Sixteen: No Accident

Chapter Seventeen: A Deadly Pas De Deux

Chapter Eighteen: Diamonds Before Swine

Chapter Nineteen: A Good Arm And A Good Eye

Chapter Twenty: Lord Of Misrule

Chapter Twenty-One: The Devil Worshipper and The Hell Stone

Chapter Twenty-Two: Mrs Trebend’S Terror

Chapter Twenty-Three: Departure For London

Chapter Twenty-Four: A Costly Comradeship

Chapter Twenty-Five: The Ideal Murder Weapon

Chapter Twenty-Six: A Frozen Purgatory

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Fragile Ice

Chapter Twenty-Eight: The Lesser of two Evils

Chapter Twenty-Nine: The Greater of two Evils

Chapter Thirty: The Tragic History of the Trebends

Chapter Thirty-One: A Christmas Miracle

About the Author

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM

JAMES LOVEGROVE AND TITAN BOOKS

The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

The Stuff of Nightmares

Gods of War

The Thinking Engine

The Labyrinth of Death

The Devil’s Dust

The Manifestations of Sherlock Holmes (January 2020)

The Cthulhu Casebooks

Sherlock Holmes and the Shadwell Shadows

Sherlock Holmes and the Miskatonic Monstrosities

Sherlock Holmes and the Sussex Sea-Devils

Sherlock Holmes and the Christmas Demon

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781785658020

Electronic edition ISBN: 9781785658037

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First hardback edition: October 2019

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2019 James Lovegrove. All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Respectfully dedicated to

SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

THE MASTER

whose fictional creations have brought delight to so many and in whose footsteps I proudly, if trepidatiously, tread

Chapter One

A FELONIOUS FATHER CHRISTMAS

“Father Christmas! Halt right there!”

These words were delivered by Sherlock Holmes in his most stentorian and authoritative tone of voice.

The object of his command, however, did not heed it. On the contrary, the festively clad fugitive lowered his head and increased his speed.

The ground floor of Burgh and Harmondswyke, the noted Oxford Street department store, was crowded with shoppers, for it was December 19th and all of London, it seemed, was out buying gifts and other seasonal essentials. There were shouts of consternation and the occasional shriek of alarm as the man dressed as Father Christmas, complete with ivy-green robe and mistletoe crown, hurtled through the milling throng. Those who did not get out of his way of their own volition, he barged aside with a ruthless thrust of the forearm. Several men and women, and even a child, found themselves on the receiving end of such rough treatment.

Holmes was hard on his heels and would have overtaken him halfway across the haberdashery department, had a shop clerk not intervened. The young fellow, dressed in an apron with the characters “B & H” emblazoned on the pocket, misread the situation and identified Holmes as the villain of the piece. Boldly he stepped into my friend’s path and made strenuous efforts to waylay him. With as much delicacy as the situation permitted, Holmes disentangled himself from the clerk’s clutches and continued after his quarry.

The delay cost him precious seconds, however, and now Father Christmas was nearing one of the sets of doors that afforded access to the street. Naught lay between him and freedom, save for one thing: me.

I had been guarding the door for the past half an hour. Inspector Lestrade and a number of police constables, all in plain clothes, were likewise stationed at the other points of egress around the building. As luck would have it, the onus of intercepting our felon now rested upon me.

It was not a task I relished, since the man was nothing short of a giant: six feet seven tall if he was an inch, and broad as a barrel around the chest. He weighed, I would estimate, in the region of seventeen stone and, to judge by his speed, was possessed of considerable strength and vitality, not to mention a determination to evade capture that bordered on desperation.

I braced myself as he approached, feeling the way a matador must when confronted with a charging bull. Father Christmas’s cheeks, above his bushy white beard, were crimson with exertion. His eyes, beneath the mistletoe crown, glared like a madman’s. His nostrils flared.

I had faced men of similar stature on the rugby pitch, and duly adopted a half-crouch, as one might when preparing to tackle an oncoming flanker.

Father Christmas, on seeing me, did not falter. If anything, he accelerated.

“Watson!” Holmes called out from behind him. “He is yours! Deal with him, would you? There’s a good fellow.”

All might have been well, had I not in the heat of the moment made a crucial mistake, namely leading with my injured shoulder. When playing rugby, I was always at pains to tackle an opponent using my good shoulder, the one that had not received a bullet from a jezail rifle wielded by a Ghazi sniper in Afghanistan. On this occasion, I neglected to take the precaution. I drove the bad shoulder hard into Father Christmas’s midriff. The collision saw both of us tumble to the floor, and the wind was certainly knocked out of Father Christmas’s sails, and for that matter his lungs; but alas, I myself was rendered helpless too. My wounded shoulder seized up from the impact, feeling as though it were suddenly gripped in a vice. I could do nothing but roll on my back, clutch the offending area and clench my teeth, hissing with pain.

Giving vent to a roar of indignation, Father Christmas regained his feet.

At that moment, Holmes at last caught up. Without hesitation he pounced, driving the giant back down to the floor. There followed a brief struggle, which ended with Holmes enfolding his opponent in a complicated baritsu wrestling hold. His arms were wrapped around Father Christmas’s neck, fingers interlaced, while one knee pressed into the small of the man’s back and the other leg locked around his thighs.

“Submit,” he hissed in the miscreant’s ear, “or I will choke you into insensibility. The choice is yours.”

There was further resistance, but Holmes merely tightened his grasp, and soon the fellow was choking, gasping for breath. He slapped the floor, indicating surrender. Holmes obligingly released him.

By now, the commotion had drawn Lestrade and his fellow Scotland Yarders. They swarmed around Father Christmas, and in no time he was in handcuffs, cursing hoarsely but volubly.

“Watson, are you well?” Holmes enquired with the utmost solicitude. He extended a hand to me, helping me to my feet.

“I have been better, Holmes,” I replied, rolling my shoulder in a gingerly manner. “I feel such a fool. In attempting to incapacitate the man, I ended up incapacitating myself.”

“Nonsense! You performed admirably. You stopped him. He is in irons. What more could one want?”

“An explanation,” Inspector Lestrade interjected in that rather testy way of his. “That is what I want, Mr Holmes. You prevailed upon me to assist you with the apprehension of a notorious jewel thief, and who do I now have in custody but good old Saint Nicholas?”

“Ah, but, Lestrade, that is where you are mistaken.” Holmes reached for Father Christmas’s bushy beard and gave it a firm, forthright tug. It peeled away, revealing itself to be false. “Tell me, whom do you see now?”

“Why, bless me!” declared the sallow-skinned, weasel-featured official. “If it isn’t Barney O’Brien!”

“Indeed,” said Holmes. “A criminal taker of treasures posing as a jolly giver of gifts. Barney O’Brien, newly released from Pentonville and already up to his old tricks again.”

“Damn you, you dog,” growled the man called O’Brien, adding a few less salubrious oaths and curses.

“A very pretty scheme you concocted, O’Brien,” said my friend, unperturbed. “Something of a step up from your usual housebreaking. I salute you. Oh, by the way, Lestrade, have one of your men go to the jewellery department and arrest a certain female assistant there. Her name, I believe, is Clarice. She shouldn’t be hard to recognise. Russet hair. Freckles. She is O’Brien’s accomplice.”

Having despatched a subordinate as requested, Lestrade said, “So where is the booty? You told me, Mr Holmes, that we would seize the culprit in flagrante. I suppose I am to rummage through his pockets in order to find his ill-gotten gains?”

“No need.” Holmes plucked the mistletoe crown from O’Brien’s head. He turned it in his hands, examining it until at last his eye alighted upon that which he sought. “You see, Lestrade? What you are looking for is right here.”

He passed the crown to Lestrade, who cast his gaze over it. “All I see are leaves and berries.”

“Look closer. All is not as it appears.”

The official peered at the item of plant-based millinery with such furrowed-browed concentration, I thought his forehead might crack. “No,” he said eventually. “I must confess myself baffled. I see nothing out of the ordinary.”

For my own part, I was in agreement with him. The mistletoe crown appeared to be nothing other than a mistletoe crown.

“Great heavens above, the berries!” Holmes snapped. “Here.” He took the crown back from Lestrade and dug thumb and forefinger into the wreaths of mistletoe. He plucked out what seemed at first glance to be an ordinary white berry. Only when he held it up to the light did I observe that it bore a distinctive nacreous lustre.

“A pearl,” I said.

“Precisely. And there are two more wedged into the crown’s interstices, here, and here. As for the others that O’Brien has spirited off the premises over the past few days, I daresay they are stashed at whatever lodging he calls home. If, that is, they have not already been sold on to a third party.”

He thrust the mistletoe crown back into Lestrade’s hands.

“Come, Watson,” he said. “Our work is done. Friend Lestrade will tidy up the last few loose ends, will you not, Lestrade? I feel Watson and I are no longer needed.”

“As you wish, Mr Holmes,” Lestrade said, with some resignation. “And am I to mention your name, when the time comes to write my report?”

“It is up to you. You may take full credit if you like. Messrs Burgh and Harmondswyke have retained my services for a handsome fee. That, from my perspective, is more than sufficient reward for my trouble. Besides, if I know my Watson, this episode will no doubt form the basis for one of his stories, and so the general public will someday come to learn of the affair and my involvement in it.”

We took our leave, donning hats, gloves and scarves and wrapping our greatcoats around us as we headed outdoors. Snow lay thickly piled on the pavements, here and there compacted to treacherous ice by the passage of countless feet, while the roadways were lined with churned-up brown sludge that was crisscrossed with wheel ruts. The afternoon sky was clear, the air bitterly sharp. That December was already proving to be colder than any in living memory, and indeed the winter of late 1890 and early 1891 is on record as one of the severest ever.

We walked a short way west along Oxford Street and thence southward into Soho, where we found a coffee house. Soon we were warming ourselves with hot drinks, and I felt the stiffness and pain in my shoulder gradually begin to abate.

“Now then, Holmes,” I said, slipping notebook and pen from my pocket, “perhaps you would care to divulge some of the finer points of the case upon which we have just been engaged.”

“While you take notes? It would be my pleasure. You did come in somewhat late in the proceedings, after all, and are not apprised of the full details.”

“Until lunchtime today I did not even know there was a case.”

“Well, it was a trifling but nonetheless enlivening matter. Put simply, it had come to the attention of the store’s owners, Mr Burgh and Mr Harmondswyke, that pearls were disappearing from the jewellery department. Not in great numbers, but incrementally, two or three at a time. They were loose gems that had not yet been strung in a necklace or bracelet or set into a ring. The department would conduct its usual stocktake at the end of each day before consigning the valuables to a safe, and always when they tallied up the pearls, they would come up short.

“At first it was assumed a shoplifter was responsible, but close observation of customers disproved the supposition. Mr Burgh and Mr Harmondswyke then hit upon the notion that the culprit must be a member of staff, and so took the step of conducting a thorough search of all the clerks in the jewellery department daily as they left at close of business. When that did not stem the outflow of pearls, they instituted a regular search of all members of staff throughout the store. Still pearls continued to vanish. That was when I was hired to investigate.

“I spent a couple of days wandering the store in various disguises. You know my penchant for such masquerades, and you will be familiar with a couple of the personae I adopted. One was an asthmatic master mariner, another a rather guileless Nonconformist clergyman. I also essayed a new role, that of a venerable Italian priest, which, I will admit, remains a work in progress but which I hold out high hopes for. Watson? Are you paying attention? Your note-taking has tailed off somewhat.”

“What’s that, Holmes? Sorry. I was distracted. Pray go on.”

The cause of my distraction was a smartly dressed and rather comely-looking young woman who had entered the coffee house shortly after us and now sat two tables away. I had caught her eyeing me in a quizzical fashion and had returned her curiosity with an amiable smile.

Holmes crooked an eyebrow and continued. “As I was saying, I visited the store several times over the course of two days, on each occasion in a different disguise, and made a careful study of the comings and goings in the jewellery department. It was mid-afternoon on the second day, yesterday, when I saw our Father Christmas enter and start greeting all and sundry in a hearty manner, customers and staff alike. A Christmas grotto has been erected in the toy department – a sizeable construction made of wood and papier mâché, designed to resemble an ice cave – wherein a Father Christmas impersonator might entertain youngsters and dispense cheap gewgaws. The gentleman, it transpires, was also under instruction to amble around the rest of the store, spreading yuletide cheer wherever he went. He whiled some time in the jewellery department chatting with the shopgirl whom I described to Lestrade.”

“Russet hair. Freckles.”

“The very one. Well remembered. The two appeared on cordial terms, to the point of clasping hands at one stage, and I inferred some sort of relationship between them. By means of a casual enquiry to the floor manager I learned that this girl, Clarice by name, had been with Burgh and Harmondswyke for several months and was regarded as a good, diligent worker. Not only that but she had recommended an intimate of hers for the job of Father Christmas, which had come vacant. She had described him as a close friend and given his name as Seamus Flynn. Physically he fit the bill, being large and ruddy-cheeked, and he even had his own costume, saving the store the trouble and expense of providing him with one.

“Already I was beginning to formulate a conjecture. Why was it only pearls that were disappearing? Why not some other, more valuable form of precious stone, of which the department had ample specimens? And by what method were the pearls being smuggled out? I rapidly hit upon the solution. Father Christmas’s mistletoe crown was the key. Even if inspected closely, a pearl might easily pass for a mistletoe berry. It was a fairly ingenious stratagem.

“I was also aware – through the auspices of the Police Gazette, whose pages are a boon to the criminal specialist – that a certain Barney O’Brien had lately been released from prison, having served three years for stealing the Baroness Willoughby-Cavendish’s diamond tiara.”

“Yes,” I said, “I recall the trial. He would have been detained for longer had the tiara itself actually been found. As it was, there was only circumstantial evidence connecting him to the crime, and so he received a more lenient sentence than he otherwise might.”

Again, I caught the young woman’s eyes upon me. She averted her gaze and resumed her business, namely scribbling industriously in a small journal. Nevertheless I had the impression that she found me interesting, and were I not a happily married man, I might have paid her the compliment of a brief word or two after Holmes and I were finished with our coffees.

“It was no great leap in logic,” Holmes said, “to deduce that Seamus Flynn and Barney O’Brien were one and the same person. I knew of the latter’s considerable height and girth, which were matched by the former’s. I even had a strong suspicion that during his brief exchange of words with russet-haired Clarice, she could have surreptitiously passed a pearl or two to him, which he had then palmed with a view to inserting them into his crown later, when no one was looking.

“To prove this beyond a shred of doubt, however, I would actually have to observe the swap taking place. Hence I returned to the store today, this time as myself, and again shadowed Father Christmas on his perambulations. In the jewellery department I watched closely as he spoke to the shopgirl. There it was! Subtle but clearly visible to one who was looking for it. A glimpse of tiny, pale objects moving from her hand to his.

“I decided to wait until after he had secreted the pearls inside his mistletoe crown. In this, I was indulging my theatrical streak somewhat. I wished to provide a dramatic dénouement to the case, by exposing not just the villain’s identity but his modus operandi, in one fell swoop.”

“Much as you did.”

“Yes, but it was nearly not to be. As O’Brien was leaving the jewellery department, I saw him pause and remove the crown as though to make some small adjustment to it. It was then that he stealthily inserted the pearls in amongst the mistletoe fronds, before returning the crown to his head. I, spying my chance, pounced.

“‘You scoundrel!’ I declared. ‘I have you now!’

“Unfortunately, I had underestimated the full extent of his strength and he was able to give me the slip. I gave chase, secure in the knowledge that he would not be able to leave the building unimpeded, since I had taken the precaution of enlisting the aid of Lestrade and his men – and yours too, of course – and the exits were covered. All the same, I feared I was to be denied my moment of glory. It was a close-run thing!”

“What about the shopgirl?” I said.

“As to her, she will doubtless confess her complicity in the crime in due course.”

“Do you think O’Brien duped or coerced her into it?”

“Neither. On the contrary, my feeling is that Clarice was actually the mastermind and O’Brien her willing foil. O’Brien has in the past not shown himself to be the shrewdest of operators. He is a skilled enough burglar but not what one would call cunning. Clarice already had the job at Burgh and Harmondswyke. She was the one who put O’Brien forward, under a pseudonym, as a candidate for Father Christmas. She could well have worked out a means of stealing the pearls and then simply inveigled O’Brien into participating in her scheme. It would not have been difficult for her. She is not unattractive.”

“Nor would O’Brien have taken much persuasion, I’d have thought, an inveterate larcenist like him.”

“Indeed. And now you have the long and the short of it, Watson. Let us congratulate ourselves. We have scored a notable success, doing our bit to ensure that this remains a time of peace on earth and goodwill to all men.”

With this ironical flourish, my friend completed his disquisition, and I put away my notebook.

Lowering his voice, Holmes then said, “That young woman who has been proving so diverting to you – do you recognise her?”

“What young woman?”

“Come now, old friend. I have seen where your eyes keep straying.”

“Well, I… I mean… She is the one whose eyes keep straying.”

“And how could any female resist a square-jawed, well-whiskered fellow such as yourself? Yet I regret to inform you that it is the both of us who fascinate the girl, not just you, for some of her glances have been directed at me. Moreover, we have seen the lass before.”

“We have?”

“She was a customer in the stationery department at Burgh and Harmondswyke. I noticed her watching us during our exchange with Lestrade. Her scrutiny was quite intense. I am surprised you were not aware of it then. And now she has followed us to this coffee house, which I cannot believe to be a coincidence, and indeed, even as I speak, she is standing up and approaching our table.”

Sure enough, the young woman was making her way towards us with a certain nervously resolute air, as though after a period of prevarication she had made up her mind to introduce herself.

“Please forgive the intrusion, gentlemen,” she said. “You are, am I right in thinking, Mr Sherlock Holmes and his companion Dr John Watson?”

“None other,” said Holmes.

“Your servant, madam,” said I, rising a little from my chair and bowing. “But you have us at a disadvantage. You are…?”

“Eve Allerthorpe. I would never normally be so forward, but when I saw the two of you in action at Burgh and Harmondswyke, and heard you address each other by name, I said to myself, ‘This is fate, Eve. Here I am, on a visit to London, and who should I chance upon amid all the millions in this city but the celebrated detective Mr Holmes, in the flesh. A rare chance has presented itself, and you must take it, girl.’ And that, after some inward debate, is what I am doing.”

“Please, have my seat,” I said, ushering her to it.

“You are too kind, Doctor. I don’t rightly know whether I should trouble you with my predicament or not. Sometimes it seems ridiculous even to me, while at other times it seems the deadliest and most serious set of circumstances and I fear that my sanity, even my very life, might… might be…”

All at once, Miss Eve Allerthorpe broke down in tears. I tendered her my handkerchief and she sobbed into it copiously. A few inquisitive glances came our way from other patrons of the coffee house, and I offered them a reassuring wave of the hand, as if to say all was well.

“Oh, I vowed I would not give in to my emotions,” the young woman said after her crying fit had run its course. “It’s just that I have been under such strain lately. You can hardly begin to imagine what it has been like. First my mother dying, and now this…”

“I think,” said Holmes, “that Watson and I should escort you to my rooms at Baker Street, Miss Allerthorpe, and there, away from prying eyes and eavesdropping ears, you may feel at liberty to unburden yourself to us in full.”

Chapter Two

THE ALLERTHORPES OF FELLSCAR KEEP

Not half an hour later, we three were ensconced in the first-floor drawing room at 221B. Mrs Hudson had banked up a roaring fire, which did much to dispel the chill, and had drawn the curtains against the onset of dusk. I had relieved Miss Allerthorpe of her overcoat, mantle and sable muff and pressed a glass of brandy into her hand.

Now Holmes, having allowed the young woman a few moments to compose herself, embarked upon a gentle interrogation.

“Miss Allerthorpe,” said he, “am I to take it that you hail from that distinguished clan whose family seat is Fellscar Keep, in the East Riding?”

“You would be correct in that assumption,” she replied with a nod.

I saw Holmes bristle somewhat at her use of the word “assumption”. It was a particular source of pride to him that he never assumed anything. However, tact and his customary politeness towards the gentler sex prevented him from upbraiding her.

In the event, the woman herself realised she had committed a solecism. “But of course, I am familiar enough with Dr Watson’s writings to know that you possess a knack for gleaning information about a person upon first acquaintance, much as though reading a page of a book. That was the case here, was it not?”

“The trace of a Yorkshire accent was a clue,” Holmes said. “Those flattened vowels, discernible even in one who is otherwise well-spoken. But also the surname Allerthorpe is an uncommon one, and given your evident affluence, it seemed more than likely that you are one of those Allerthorpes.”

“Our renown has obviously spread further than I thought.”

“It would be hard not to have heard of one of the richest families in the north, if not all of England, whose collective wealth derives from coal mining and wool, in which trades Allerthorpes became preeminent during the Industrial Revolution.”

“I wonder what else you can tell about me,” Miss Allerthorpe said. “Something more obscure, perhaps.”

“Well, since you have thrown down the gauntlet, madam, allow me to accommodate you. Judging by your youth – you can be no more than twenty years of age – you belong to the most recent generation of the Allerthorpe dynasty. You are as yet unmarried, as you wear no wedding ring. You are also fond of poetry.”

Miss Allerthorpe’s eyes widened. “How on earth can you know that? Outside of my immediate circle of acquaintance, there can be no one aware that poetry is my passion.”

Holmes flapped a dismissive hand. “As Watson took your overcoat and hung it up, I spied the slim, well-thumbed volume of Keats protruding from the pocket. That was all the evidence necessary. You write poems of your own, what is more.”

Her surprise at his deduction was this time not as great. “I suppose that is obvious. The odds are high that those who read poetry are versifiers themselves.”

“Odds have nothing to do with it,” said Holmes. “I observed you at your table in the coffee house. Thanks to our relative positions I could not see precisely what you were writing in your journal, but the distance your pen covered when moving from left to right was shorter than the full breadth of the page by some margin. Short lines customarily denote poetry. Added to that, you crossed out and rewrote several times, actions suggestive of someone in the throes of creative composition.”

“I see. Anything further?”

“I would submit that you are in a state of high tension and have been for some days.”

“I already told you that I am under great strain.”

“And it is plain not only in the slight tremble that attends your every gesture, but in your recent significant weight loss.”

“It is true I haven’t had much of an appetite in the past few months,” Miss Allerthorpe confessed. “I scarcely dare ask how you divined that.”

“Your blouse has been recently taken in, as is evident from the thickness of the new seams. A woman of your means and background would not wear an item of clothing that was not tailored to her figure. Her blouse would neither be borrowed nor hand-me-down. Yours has been altered because it no longer fits you as once it did, a state of affairs which must be recent, else you would by now have purchased a whole new wardrobe better suited to the slimmer you. And would I be mistaken in inferring that you have a younger sibling? A brother?”

“I do. Erasmus.”

“I thought as much.”

“Perhaps you have read about him in the society pages. Raz has been known for his boisterous activities, reports of which sometimes appear in the gossip columns.”

“No, I had not the faintest idea about his existence until I observed the small scar on your face.”

“You mean here?” Miss Allerthorpe’s hand went to her left eyebrow, just above which lay a small, all but imperceptible blemish.

“The very one. Its faintness bespeaks a wound sustained some years ago, in other words in your early youth, when, as the good Doctor here will attest, the body heals more quickly and efficiently than in adulthood. Your brother is the one who inflicted it upon you during a bout of horseplay.”

“It is absurd that you could know that.”

“I will admit I was somewhat chancing my arm with the deduction,” said Holmes. “I felt moved to venture it regardless, and the gamble paid off. You see, my own brother, Mycroft, has a very similar scar in almost the exact same spot, and I was the culprit. I gashed him with the tip of a wooden sword while we were playing at pirates one afternoon. It seemed at least plausible that your wound was inflicted in a similar manner. It tends to be younger brothers who are to blame for such malfeasances, and older siblings their victims.”

“I was ten, Erasmus eight,” Miss Allerthorpe said. “He was pretending to be Saint George, riding a hobby horse and wielding, like you, a wooden sword. I was saddled with the role of the dragon he was bent on slaying. Raz was always a bumptious boy, lacking in self-restraint, and his enthusiasm for the game got the better of him. He has marred my features but I have forgiven him.”

“Hardly marred!” I declared. “Why, if Holmes had not mentioned the scar, Miss Allerthorpe, I would never even have realised it was there. Your looks are quite undiminished for its presence.”

“Thank you for saying so, sir.”

“Watson’s gallantry exceeds mine,” said Holmes, feigning chagrin. “Consider me rebuked for my temerity in raising the subject at all. But now that I have discharged my duty by making these few small observations about you, Miss Allerthorpe, perhaps you are ready to expand upon the nature of this ‘deadliest and most serious set of circumstances’ in which you find yourself.”

“Where to begin, Mr Holmes?”

It was a rhetorical question but Holmes answered it anyway. “You mentioned that your mother is dead and that this heralded the onset of your woes. There might be a good place to start.”

Eve Allerthorpe steeled herself with a sip of brandy and commenced her narrative.

“My mother passed away a year ago almost to the day,” said she. “She was never what one would call the most stable of characters. Her temperament was mercurial, her mood as changeable as the weather over the Yorkshire Moors. Some might even go so far as to call her mad. She could be angry and vituperative, downright venomous at times. Yet she could also be tender and loving, and on the whole was devoted both to Papa and to her two children. That made her death in one sense surprising and in another sense not surprising at all.”

“How so?”

“Mama took her own life, you see.” Miss Allerthorpe faltered. “Even now it is difficult for me to discuss.”

“I understand. Take your time.”

“Our home – Fellscar Keep, as you have said – is an immense, rambling edifice of towers, wings and battlements, perched on an island in the middle of a lake. One evening last December, my mother was in a particularly volatile frame of mind. She had endured some minor setback during the day – a maidservant had, as I recall, accidentally scorched one of her favourite dresses with the smoothing iron – and it threw her into a fit of rage and recrimination, as such things were apt to. Her anger, though it could often be visited upon others, was just as often visited upon herself, and so it was in this instance. Mama somehow blamed herself for the damaged dress, saying that it was no better than she deserved and that a wretch like her should not expect anything ever to go her way. All my father’s efforts to placate her were to no avail. Eventually she went to her room and locked herself in.”

“Her own bedroom? She and your father slept separately?”

“She was a restless sleeper. Papa preferred his slumber not to be disturbed by her wakefulness. At any rate, from past experience we knew we were unlikely to see any more of her until the following morning, when she would doubtless emerge all smiles and laughter, as though nothing untoward had occurred. Around midnight, however, she was heard rushing along the corridors of the castle, wailing at the top of her voice, and…”

Miss Allerthorpe strove to maintain her poise.

“And then,” she said, “she took herself to the top of the tallest tower, which lies in the castle’s east wing, opened a window and threw herself out, into the lake. The servants dragged the water all night, under Papa’s supervision, but it wasn’t until first light that the… that the body was eventually recovered.”

I made sympathetic noises, while Holmes quietly steepled his long fingers and pressed their tips to the groove above his upper lip.

“You can well imagine the horror of the incident,” Miss Allerthorpe said, “and the shock Mama’s death wrought upon us. Erasmus and I, in particular, were distraught with grief. Our mother would never have abandoned us in this way if the equilibrium of her mind had not been seriously disturbed, we knew that. But looking back, we had perhaps known all along that it was not unlikely she might meet such an end. Often when Mama’s depressions became profound, she would cause harm to her own person, by pricking her arms with a hatpin, for instance, and raking her fingernails down her cheek. My father had consulted the best alienists in Harley Street, to no avail. There seemed no cure, no hope of change. All any of us could do was accept and endure. Yet it was never wholly bad. There were happy times, too. When she was in one of her ‘up’ phases, my mother had the sunniest of dispositions and there was nobody whose company I would rather have kept.”

“A tragedy is no less appalling when one can see it looming,” I said.

“Quite the opposite, Doctor. The inevitability makes it worse. I will not say that my present difficulties stem directly from Mama’s suicide. I will say, though, that the death has cast a pall over the household, which has yet to lift fully. Put simply, none of us has been the same since. Papa, always a rather remote person, has become positively aloof, and his temperament, once equable, now tends towards the irascible. Erasmus… Well, his behaviour was troublesome to begin with, and has done anything but improve. It was hoped, though, that this Christmas might bring about a change in our fortunes.”

“Why should that be?” asked Holmes.

“If there is one thing that unites the Allerthorpes, Mr Holmes, it is a love of Christmas. At this time of year, the wider family travels from near and far, converging on Fellscar Keep to celebrate the season. It is a tradition going back a good five decades, instituted by my grandfather, Alpheus Allerthorpe, and rigorously, one might even say religiously, maintained ever since. The castle opens its doors and plays host to a week-long revel. There is feasting, carolling, gift-giving. There is also an opportunity to renew family ties and mend any fences that might need mending. Only once has the event ever been cancelled.”

“Last December, in the wake of your mother’s death.”

“Precisely. This year, it is hoped we may resume as before. Or rather, it was hoped. But before I get to that, Mr Holmes, I must furnish you with one last detail which may or may not be of relevance.”

“Pray do.”

“As you surmised, I am twenty years old. My twenty-first birthday falls this coming Wednesday.”

“Christmas Eve,” I said.

“That is right. I was born on Christmas Eve.”

“Hence your first name.”

“Again, that is right.”

“Watson,” Holmes remarked to me superciliously, “never let it be said that your powers of deduction are not at least the equal of mine.”

I rewarded him with a dusty stare.

“When I turn twenty-one,” Miss Allerthorpe said, “I am in line for a sizeable inheritance. It is a legacy left me by my aunt Jocasta. She died when I was very young. I hardly remember her, beyond a few vague impressions. Mostly I recall a rather formidable woman, brusque but well-meaning, with a voice that could be heard several rooms away. Although she was my mother’s sister, her senior by just over a year, the two of them could scarcely have been less alike. Mama, as I have made clear, was anxious and neurotic. Aunt Jocasta was as down-to-earth and dependable as they come. In terms of physique, Mama was tall, thin and brittle-seeming; Jocasta was short and sturdily built, practically as wide as she was tall. Mama did not concern herself with matters beyond the domestic sphere, whereas Jocasta was engaged in politics and a staunch advocate of the rights of women. She believed that women should be educated as men are and given the vote, and she was not afraid to voice her opinions. I am told she once stormed a general election campaign meeting being held by her local Member of Parliament and chanted demands for universal suffrage. Her protest caused disarray and brought the proceedings to a premature halt, resulting in her forcible eviction and an arrest for breach of the peace. I cannot attest to the truth of that. It may just be a family fable. I do know that Jocasta was reviled as a troublemaker in some quarters, and in others considered a radical heroine.”

“And you are the sole beneficiary of her will?”

“Yes. Her husband was a prominent sugar plantation owner, Sir Cyril Keele, who died a few years into their marriage. He contracted typhus while visiting one of his estates in the Caribbean. Upon being widowed, Aunt Jocasta sold off his holdings and invested the capital in stocks, living very comfortably thereafter on the interest. She was childless, and her portfolio and cash savings have been held in trust for me since her death. Everything, minus a few small disbursements to charities, will become mine in just a few days’ time.”

“It is unusual for a legacy to be passed down the distaff line,” said Holmes. “Yet, if your aunt was as favourable towards the advancement of her own sex as you say, then it makes sense. You, I imagine, are her nearest female kin, aside from her late sister.”

Miss Allerthorpe nodded. “Jocasta, by all accounts, regarded my mother as sufficiently well-off already, for she had married into the Allerthorpe family. She knew, moreover, that my father, as husband, would gain control of the money if it went to Mama, and Mama herself might derive no direct benefit from it at all. She chose to confer it on me instead. You must appreciate that, as a daughter, I will profit in no way whatsoever from Papa’s estate. Upon his death, his money will be passed to my brother in its entirety, as will the title to the castle and Allerthorpe lands, which are extensive. Jocasta felt I ought to be of independent means, beholden to no one – no man – for my living. I believe there is an additional reason, too, why she did not regard my mother as a suitable recipient for the legacy. It is implied by a codicil in the will.”

“Which stipulates…?”

“That I am to receive the money only if, upon reaching the age of twenty-one, I am ‘sound in mind’. Otherwise, I do not see a single penny.”

“She deemed your mother not ‘sound in mind’, then.”

“With some justification. And it would seem she feared the possibility that I might follow in Mama’s footsteps. Madness is often hereditary, is it not?”

Miss Allerthorpe aimed this question at me. I replied, “Current medical thinking has moved on from the belief that mental aberration arises from social background and ‘sinful’ behaviour. According to Henry Maudsley, the eminent psychiatrist, just as a propensity towards certain diseases may be passed on through the blood, so may a propensity towards certain abnormal mental traits. It is not axiomatically the case, however, that the child of a mad person will likewise become mad. The trait may stay dormant.”

“Aunt Jocasta would certainly seem to have made provision for the possibility that, in me, the trait is not dormant,” said Miss Allerthorpe. “I imagine she felt that if I ended up like my mother, I would be incapable of properly handling my newfound wealth and thus lay myself open to criticism and exploitation. It would set a bad example if a woman were seen to lack the wherewithal to manage large sums of money. It would undermine all that Jocasta strove to prove during her life.”

“What would happen to the legacy if, heaven forfend, you were to be certified unsound in mind?” said Holmes.

“In that instance, the totality is to be apportioned equally amongst family members of my generation. That comprises a number of my cousins and, of course, Erasmus. Each would receive currency and shares worth in the region of four thousand pounds.”

Holmes gave a low whistle. “A tidy sum. Yet, with just five days remaining, it does not strike me as likely that you will be considered unfit to receive your legacy, Miss Allerthorpe. Although at the coffee house you implied that your sanity is imperilled, I see scant sign of it myself. You are anxious and agitated, yes. But mad? Hardly.”

“Little do you realise, Mr Holmes, how close I am to losing my wits,” said the young woman, her hand fluttering to her throat. “There have been times over the past few days when I have truly doubted the evidence of my own eyes, and on one occasion I have been visited by such terror that I can barely bring myself to think about it, let alone talk about it.”

“Yet you must talk about it, if I am to help you.”

“I know. Dr Watson, would you be so kind as to recharge my glass?”

I helped Miss Allerthorpe to more brandy, which she drank almost to the bottom before carrying on.

“When I relate to you now, gentlemen, the series of incidents that have lately befallen me,” she said, “you will perhaps be incredulous and dismiss it all as nonsense. If, on the other hand, you believe me, then you could be forgiven for thinking that I have indeed taken leave of my senses. I am being haunted, you see. Doubly haunted.”

“By a ghost?” said Holmes.

“By a ghost, and by a creature from nightmares.”

Chapter Three

THE BLACK THURRICK

I could see Holmes doing his best to mask his scepticism. In his view, ghosts did not exist, nor any other form of paranormal phenomenon. He was adamant that that which purported to be otherworldly would, when subjected to proper analysis, invariably be exposed as a misapprehension of the data, a hitherto undiscovered natural occurrence, or a downright falsehood. As far as he was concerned, the bright, hard light of empiricism could disperse all shadows.

I myself was less confident when it came to such matters. To me there seemed plenty of room in this world for mysteries that science and logic could not explain. Human understanding only reached so far before it ran up against the ineffable and the irrational, and without that extra, unknown dimension, life would truly be a poor, drab affair.

At any rate, where Miss Allerthorpe’s words served to have no effect upon Holmes other than to cause him to purse his lips, they sent a small chill up my spine.

“With regard to the ghost,” she said, “perhaps I overstated when I said I am being haunted by it. I have not personally experienced any of the various manifestations that might lead one to conclude that a revenant walks the corridors of Fellscar Keep. There have been reports from several of the servants, however, concerning inexplicable noises in the castle’s east wing at night. Thuds, bangs and suchlike. Strange breezes, too, that extinguish candle flames like a puff of breath. I do not frequent that part of the building, so cannot attest to any of this first-hand.”

“The east wing is where your mother took her own life,” said Holmes. “I imagine it holds negative associations for you.”

“Exactly. There is little call for me to go there anyway. It is a somewhat remote corner, far from the usually inhabited sections of the castle. Only during the Christmas family get-together, when we are overrun by houseguests, are its rooms occupied. For most of the year it lies, as it were, fallow.”

“The question, I suppose, is whose ghost it might be. How long have these manifestations, as you call them, been occurring?”

“For several months now. Since spring at least, if not earlier.”

“I am hesitant to suggest this, but might the spectral shade conceivably be that of your late mother?”

Miss Allerthorpe nodded. It was apparent that this unhappy thought had already occurred to her. “Hence it is fair to say that I am being haunted by it, even if I have not seen it with my own eyes. What if it is my mother? What if Mama’s restless departed spirit has returned to the very place where she drew her last breath?”