Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Sherlock Holmes

- Sprache: Englisch

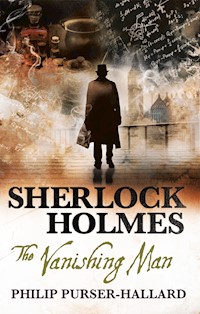

A brand-new Sherlock Holmes mystery from acclaimed author Philip Purser-Hallard. A Mysterious Disappearance It is 1896, and Sherlock Holmes is investigating a self-proclaimed psychic who disappeared from a locked room, in front of several witnesses. While attempting to prove the existence of telekinesis to a scientific society, an alleged psychic, Kellway, vanished before their eyes during the experiment. With a large reward at stake, Holmes is convinced Kellway is a charlatan – or he would be, if he had returned to claim his prize. As Holmes and Watson investigate, the case only grows stranger, and they must contend with an interfering "occult detective" and an increasingly deranged cult. But when one of the society members is found dead, events take a far more sinister turn…

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 394

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

About the Author

Sherlock Holmes Cry of the Innocents

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Sherlock Holmes: Cry of the InnocentsCavan Scott

Sherlock Holmes: The Patchwork DevilCavan Scott

Sherlock Holmes: The Labyrinth of DeathJames Lovegrove

Sherlock Holmes: The Thinking EngineJames Lovegrove

Sherlock Holmes: Gods of WarJames Lovegrove

Sherlock Holmes: The Stuffof NightmaresJames Lovegrove

Sherlock Holmes: The Spirit BoxGeorge Mann

Sherlock Holmes: The Will of the DeadGeorge Mann

Sherlock Holmes: The Breath of GodGuy Adams

Sherlock Holmes: The Army of Dr MoreauGuy Adams

Sherlock Holmes: A Betrayal in BloodMark A. Latham

Sherlock Holmes: The Legacy of DeedsNick Kyme

Sherlock Holmes: The Red TowerMark A. Latham

Sherlock Holmes: The Devil’s DustJames Lovegrove

COMING SOON FROM TITAN BOOKS

Sherlock Holmes: The Spider’s WebPhilip Purser-Hallard

PHILIP PURSER-HALLARD

TITAN BOOKS

Sherlock Holmes: The Vanishing ManPrint edition ISBN: 9781785658426Electronic edition ISBN: 9781785658433

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UP

First edition: June 20192 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2019 Philip Purser-Hallard. All Rights Reserved.Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book?We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at:[email protected], or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offersonline, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:www.titanbooks.com

To all those who have preceded me in John Watson’s footsteps,but especially Stuart Douglas, Kelly Hale and George Mann.

FOREWORD

I recently received through the post a package sent from my friend Sherlock Holmes’s retirement retreat in Sussex, which upon inspection proved to contain a bundle of papers relating to an investigation that occupied Holmes and myself during part of the September of 1896. Some of them I remember my friend showing me at the time; others are new to me. Though Holmes has made occasional annotations, there was no letter accompanying the enclosed material. I have nevertheless taken this as conveying his view that the time has come for the story of the case to be told.

In preparing this account for publication, I have remained faithful to my contemporary impressions, resisting the temptation, beyond some necessary tidying and polishing and the checking and correction of certain facts, to elaborate upon the notes I set down shortly afterwards. However, some of those papers which Holmes must have acquired in the years since demonstrate that the incident of the Evolved Man was one with ramifications that I at least, and perhaps even he, did not fully grasp at the time.

Although their relevance is sometimes tangential, it is clear that Holmes considers all these documents to be of potential interest. I have therefore interspersed them between the chapters of my own account, to provide the reader with a more complete understanding than was available to us then.

John H. Watson, MD, 1928

CHAPTER ONE

‘In the space of an hour’s walk this afternoon,’ Sherlock Holmes told me, ‘I have observed three pickpockets, a housebreaker and a man who disappeared.’

I stared at him, a little befuddled. He had returned from his constitutional, to all appearances energised and invigorated, to find me in the chair by the fire in the cosy fug of our rooms. I had earlier declined to join him on his perambulations on the grounds that the afternoon was wet and chilly, and my old war-wound had been troubling me. Though I had certainly been reading the newspaper when he left, I confess that I might have fallen into a light doze during his absence.

‘Disappeared?’ I asked, struggling to think of an intelligent reply. ‘That hardly seems possible on a London street in daylight, even when the sky is so dark with cloud. But what,’ I added, ‘do you mean about the pickpockets and housebreaker? I can’t believe you’ve seen four crimes committed during one short walk.’

The time was, I noted with a surreptitious glance at the clock, about five-thirty in the afternoon. The day was a damp Tuesday in September. After a sunny morning, heavy clouds had swept in over London during lunch, surrendering a burden of water which had had our window-panes resounding like a drum – albeit a peculiarly soothing one – all afternoon. Outside, I saw as I opened the window for a breath of air, the gutters still flowed murkily. Cabmen and their horses grumbled beneath their oilskins, while pedestrians jostled their way through the puddles under umbrellas, or with droplets cascading from their hats. It seemed an inauspicious day for crime, let alone for unnatural disappearances.

‘Alas,’ said Holmes, vigorously stoking the fire, ‘I saw none of them breaking the law. I merely inferred their intentions from their behaviour and manner. The pickpockets were fleet-footed, nimble-fingered fellows, walking briskly at the side of the pavement nearest the road, unencumbered by umbrellas. Their coats were too light for the weather, short in the arm and tight-fitting about the cuffs, with deep pockets. Their eyes darted about as they walked, sizing up each person they passed.’

He threw himself down into his armchair and continued. ‘The housebreaker was a different specimen, thin as a wire with large, strong hands. Though he could have moved as quickly as any of the pickpockets, he instead trudged slowly through the rain, gazing up at the buildings around him with a rustic’s curiosity. He lingered for a while on Baker Street, lit a cigarette, took in his surroundings along with his leisurely smoke, then trampled the cigarette-end and went his way.’

As I re-seated myself I wondered, not for the first time, how Holmes could be certain of such firm convictions based on what were surely mundane observations. ‘Anyone might take an interest in his surroundings while enjoying a quiet smoke in the street,’ I admonished him. ‘I’m sure I’ve done it myself.’

Holmes smiled. ‘I would venture, Watson, that you have not chosen to linger opposite a bathroom window which hangs ajar on a broken catch, and which might with judicious footwork be reached from the street at dead of night.’

‘Not chosen, no.’ I added obstinately, ‘But I might happen to.’

‘Perhaps, Watson, perhaps. By that time I was wanting the comforts of home, or I should have followed the man and seen whether the coincidence repeated itself further down the street. In any case, Mrs Hudson must advise her counterpart at Number 213 to have that catch mended with all haste.’

I recalled the rest of his peculiar statement. ‘But what did you mean about the other man?’ I asked, allowing a note of amusement to enter my voice. ‘Did he fade away before your eyes, or did you merely infer from his manner an intention to disappear at some time in the future?’

Holmes said good-naturedly, ‘Ah, but that case was different again. I confess that the man I speak of did not vanish in front of me. I could discern, though, that he had recently disappeared from his previous life. The number who do so might surprise you, Watson, steadfast and reliable as your own presence is.’ He stood again and paced across the room, to gaze out of the window into the Baker Street drizzle. ‘Some leave wives and families, of course, whether for some new infatuation or simply because they feel oppressed by their obligations. Others flee the consequences of a crime or scandal, or from debt. And where better to remain invisible than in a city of so many million souls?

‘The man I saw was dressed like a workman and his hands bore cuts and the beginnings of calluses, of the kind one sees on operators of machinery – but all were recent, while the shape of the same digits showed the deep groove of a pen, telling of years spent as an office clerk. His chin was raw from unaccustomed shaving, and he sported whiskers of perhaps a month’s growth, inexpertly kempt although they were the kind in which the wearer normally takes some pride. He doffed his cap to ladies, but with a sense of novelty to the movement, as if used to wearing a different kind of hat entirely.’

I remained sceptical. ‘It seems a rather flimsy chain of reasoning on which to base such a conclusion. Perhaps the man had simply suffered a recent change of circumstances.’

Holmes continued. ‘As he passed beneath a clock I saw him absent-mindedly reach to his midriff, thinking to take out a pocket-watch and set it, before recalling that he wore no waistcoat and carried no watch. He glanced nervously at the faces of those around him to see whether he had been observed. When he saw my eye on him he blanched and hastened away. He had become visible again, and that is what a vanished man fears the most.’

Holmes turned to me and smiled again. ‘But here we are, Watson, discussing the disappeared when we are about to be favoured with an unexpected appearance.’

I went to the window. In the street beneath were two figures, picking the way through the puddles to our doorstep. The rain persisted still, and all we could see of them were their legs and the black domes of their umbrellas.

‘There’s not a lot you can deduce from that,’ I observed, knowing as I said it that I was in all likelihood handing Holmes another opportunity to prove me wrong. He barked an amused ‘Ha!’ and, shutting the window against the cold, crossed the room to stand before the fire.

A few moments later the sitting-room door opened and Mrs Hudson ushered in two gentlemen, now divested of their outer garments. The senior of the two was a handsome man of about sixty, clean-shaven, with bright eyes and swan-white hair flowing from a high, intelligent forehead. His companion was under thirty years of age, tall and slight, with dark curly hair and large eyes.

‘Ah, Sir Newnham Speight,’ said Sherlock Holmes at once, before Mrs Hudson could introduce them. ‘May I present my associate, Dr Watson?’

The older man nodded politely to me and said, ‘But I wasn’t aware we’d met, Mr Holmes. I’d have thought I would have remembered.’

I recognised Sir Newnham’s name, of course. The reader will doubtless recall him too, as the inventor lauded by a grateful nation for such practical boons as Speight’s Self-Igniting Tinder-Pipe, Speight’s Doubly-Adjustable Bedstead with Integrated Mattress, Speight’s Rotary Clothes-Press Wardrobe, and Speight’s Miniature Bedside Tea-Urn with Integrated Alarm Clock. I owned one of the last myself, a present given in gratitude by an eccentric patient, which I had never yet used.

‘No more we have,’ Holmes replied, gratified by the man’s perplexity. ‘But I had the opportunity to observe your umbrellas as you arrived outside. Each is unmistakeably a Speight’s Super-Collapsible Pocket model, but with certain ingenious adjustments. I take it that today’s inclement weather has been an opportunity for you to test out a prototype for a more advanced design?’

‘Two different prototypes, in fact,’ the younger man said in a light, musical voice. He seemed amused by Holmes’s odd manners, and introduced himself as Talbot Rhyne, Sir Newnham’s assistant. ‘Sir Newnham has the brolly with my improvements, and I the one with his. We’re carrying out a comparative field-test.’

‘Capital!’ cried Holmes. ‘Do you hear that, Watson? The perfect marriage of the entrepreneurial and the empirical spirit.’

‘You chose a day that suited the experiment, anyway,’ I said. ‘Won’t you sit down and take some tea?’

‘Tut, Watson,’ insisted Holmes, ‘they haven’t come for tea.’ My view was that given their chilly journey they might welcome it nonetheless, but Holmes was unlikely to succumb to persuasion when gripped by such an enthusiastic mood. ‘Take a seat, gentlemen, and tell Dr Watson and myself what is on your minds this sodden evening.’

‘It’s a very peculiar affair, Mr Holmes,’ said Sir Newnham as they both settled into chairs. Though perfectly articulate, his voice retained echoes of the working-class Londoners outside on the street, and I recalled reading that Speight, a millionaire several times over and knighted by the Queen to boot, was a self-made man of humble origins. ‘I fear it’s not really in your usual line, but if there’s a man in London who can explain it to me, it’s yourself.’

‘I am already intrigued,’ said Holmes. ‘If there is one thing guaranteed to endear a case to me, it is that it should be peculiar. Pray proceed.’

‘Well, that’s part of the question,’ Sir Newnham Speight said. ‘It may not even be a “case” in the criminal sense. Something has happened, certainly – something decidedly out of the ordinary – and the explanation may well involve a crime of some sort. But at the moment it’s impossible to say whether Thomas Kellway is missing or dead.’

‘That is distressing,’ I suggested sympathetically, remembering Holmes’s earlier comments about men who abandon their positions in life, ‘but perhaps not so very unusual.’

‘It’s the possibilities that make it so, Dr Watson,’ Talbot Rhyne put in eagerly. ‘You see, it may be that Kellway is one of the greatest hoaxers in history, or it may be that he has somehow managed to transport himself to the planet Venus. I think that puts it in the realm of the remarkable, at least.’

‘The planet Venus?’ I repeated in astonishment.

Holmes smiled tightly. ‘In principle, gentlemen, it is a trivial matter to guess which of your alternatives is the more likely. I have known a considerable number of hoaxers during my career, but am yet to meet a single interplanetary traveller. I imagine, though, that you have more to tell me. Watson, I believe we may after all benefit from some tea, while Sir Newnham recounts this surprising story to us from the beginning.’

Our guests settled themselves while I rang for Mrs Hudson and outlined our requirements. As she departed, Sir Newnham began his tale.

‘Among my other interests, I am the Chairman of the Society for the Scientific Investigation of Psychical Phenomena. Our aim is to investigate through experiment and observation those phenomena commonly ascribed the label “psychic” – thought-transference, mental action at a distance, clairvoyance, et cetera – with a view to either proving or disproving their existence.

‘I see you frown, but you must understand that my own interest isn’t in the mystical mumbo-jumbo with which imaginative people so often surround such claims – the spirit world and Druids from Atlantis and the like. I’m a scientist, not a metaphysician. My interest lies in research, and that obliges me to be as open-minded on this question as on any other.

‘I will admit that the Society attracts members of various types, with varying philosophical and even religious persuasions. Provided they pay their dues and don’t interfere with the experiments, they’re all welcome. My own view is not fixed as to the veracity of those exceptional phenomena that witnesses in history have from time to time reported – levitation, precognition, bilocation and what-have-you. So far I haven’t seen compelling evidence one way or the other.

‘I am firm, though, that if such things exist then they are neither magical nor miraculous, but can be measured and observed like everything else in the universe, and on that basis analysed, predicted and eventually reproduced. If ever that were done successfully, then the potential contribution to future science would be incalculable. Alternatively, there may be nothing at all to measure – but to the scientist a discovery of truth is never truly a failure.

‘Over the years I have found it helpful to set up the facilities for my researches in the more conventional sciences at my home, Parapluvium House in Richmond, and among these I’ve constructed an annexe where claims of extraordinary phenomena may be tested under a variety of controlled conditions. Its most salient feature is a set of three Experiment Rooms in which subjects may be isolated from one another, and from any necessary experimental materials, so that we may be sure that any interaction between the rooms is exclusively mental.

‘For such trials we need subjects, and it is necessary to encourage those who believe themselves to be gifted in the psychical arena to come forward. Such persons are generally reluctant to subject themselves to a full scientific investigation, but this is not always because they are dishonest. Many may be quite sincere in their claims, but mistrust our motives, or lack the education to understand our aims, or fear that the experiments will be invasive or painful.

‘To overcome such reluctance, I have made a standing offer of a reward of ten thousand pounds to any claimant who can successfully convince the Committee of the Society, in a simple test, of a psychic ability or corresponding phenomenon.

‘Such an outcome would be merely the start of the process, of course – the condition for the reward is the Committee’s satisfaction, whereas the criteria for scientific proof would be a great deal more rigorous, and could take months of repeated experiments. If any trial subject were to pass the first test, we would naturally offer all possible inducements to persuade them to stay on. However, in the three years since the reward was first offered, several dozen claimants have come forward, and none have satisfied the Committee’s credulity, let alone the strictures of experimental proof.

‘At least – that was certainly the case last night. It may no longer be possible to say so this morning.’

Sir Newnham fell broodingly silent for a few moments before continuing. ‘Ten thousand is a very substantial sum, of course,’ he said. ‘It has attracted a few subjects who came close enough in the experiments to persuade some of the Committee that they were genuinely gifted. It has brought us many who are sincerely deluded, and a few overconfident fraudsters. The latter group have sometimes been remarkably ingenious. So far we’ve found out all their deceptions, but it remains a fear of mine that one day I will be taken in by some hoax.

‘That, then, is the background to our current quandary. I shall proceed to the more immediate events.

‘A little over two months ago I received a letter from a man named Thomas Kellway, who informed me that he had psychic abilities. He prefaced it with a lot of waffle, as they generally do. In any case, while Kellway’s spiel may have been about how interplanetary etheric influences had boosted certain abilities in him that are latent in all of us, his gist was that he could make an object move some distance away using the power of his mind – the technical term is “telekinesis”. Our experimental facilities can certainly put such phenomena to the test, so I invited him to come and meet me.

‘My first impressions of the man were favourable enough. He is a soft-spoken Yorkshireman, a fine physical specimen, perhaps fifty years old but hale and strong. Intelligent too, and articulate, with a calm, persuasive way about him. His most remarkable characteristic, though, was that he was entirely bald – not a hair on his head, not even an eyebrow, nor yet on his hands.

‘I found him eccentric, to be sure, but no more so than many who come our way. No more so than some in our Society, if truth be told. We encounter freemasons, theosophists, spiritualists, vegetarians – all sorts. He attended last month’s meeting of the Society, and many of them were quite taken with him. He has called at several of our houses, including mine, on a number of occasions since.

‘As I have said, Kellway’s particular fancies are in the cosmological line. He believes – or perhaps I should only say that he claims – that he has been remotely influenced since before his birth by superior intelligences from the second planet in our solar system.

‘These Venusians supposedly established a form of pre-natal psychical communion with Kellway, and under their influence he has become a more highly developed form of human being, mentally and physically superior to the rest of us – although he insists that anyone can become such with the proper discipline. An “Evolved Man” is what he calls himself – the next stage of human development – although I have also heard him use the term “Interplanetary Man”. He told me that he was born bald, hair being a useless vestige of mankind’s evolutionary past. He maintains that for similar reasons he lacks the normal vermiform appendix, though I am of course in no position to confirm that statement and I cannot imagine how he can be certain of it either.

‘According to Kellway, the goal of the Venusians, having raised all life on their planet to the peak of its evolutionary potential, is to assist those of us here on Earth to perfect ourselves likewise, becoming angelic paragons like the Venusians themselves. To do him justice, Kellway claims merely to be a step along that road rather than its final destination. Supposedly the Venusians were blessed in this way aeons ago by beings from Mercury, and intend that we in turn shall show the same favour to the inhabitants of Mars, each world bestowing enlightenment on the next one out from the Sun, which is the original source of these emanations of divinity.

‘His cosmology is rather primitive, you see, despite its modern veneer. He speaks with an occasional rather biblical turn of phrase, which I might have put down to a non-conformist upbringing were it not for these messianic pretensions of his.

‘It was decided early in our Society’s existence, however, that we would judge our subjects on the practical results of our experiments, not on their own beliefs. I agreed with Kellway that we would conduct a trial to prove or disprove his ability. We agreed the form that this experiment would take, which is our standard one for telekinesis, though with a few modifications. The date was set for yesterday.

‘Kellway would be locked in an otherwise empty room, next to another, similar room, also locked, which would also be empty but for three things: a table, a closed wooden box on top of it, and an ordinary billiard ball placed inside the box. The intervening wall would mean that Kellway would be unable even to see the experimental materials. His task would be to open the box in the next-door room and remove the ball, using nothing but the power of his mind.

‘The Experimental Annexe was built to my own specifications, two years ago. I hope you will take the opportunity to inspect it yourself, Mr Holmes. In the meantime, allow me to describe it to you.

‘It is reached from the house via a passage from my chemical laboratories, or from the grounds through an external door. Both of these doors are located in the antechamber which adjoins the three Experiment Rooms, which are in a row next to one another and are designated A, B and C. The experiment required that Kellway occupy Room A, with the experimental materials in Room B. Each room is a cube, eight feet by eight feet by eight feet, with a large glass panel in the door and a window at the top of the far wall. The windows can be opened for comfort during hot weather, but they are narrow and barred, as well as high. A cat might squeeze through one of them perhaps, but not a man. The doors are of a design normally used in store-rooms, which can only be locked and unlocked from the outside, and the lock’s manufacturers advertise it as unpickable. There are no connecting doors between the three rooms, of course – that would hardly serve the purposes of the experiment. Have I been clear enough, Mr Holmes?’

Holmes said, ‘I believe I can visualise the arrangement. I, too, hope that I will be able to examine it in person before long. Pray continue.’

‘Well, Kellway told me that he could accomplish the task, but he had certain stipulations. He spoke of charging up his psychical energy like a battery, until he had a sufficiency of it to perform the task – those may not have been his precise words, but that was his drift. This would, he insisted, take many hours of meditation to do. This process would have to begin at sunset, with Venus still visible in the sky. He added that experience had shown him that direct artificial light would interfere with the frequency of his psychic vibrations, and would render the experiment futile.

‘I need not say that this rang alarm bells for me – in my experience, a subject who prefers to work in the dark has something to hide. However, it transpired that Kellway had no objection to Room B being well lit, nor the anteroom, merely his own room. Each has its own independent electric light, so the box on its table would be illuminated clearly throughout, while Kellway himself would be visible, though not strongly lit, by the brightness from the anteroom. Given the aim of the experiment, I felt that, provided we could observe the experimental materials, it would be less important to see exactly what Kellway was doing. After some consultation with the members of the Society Committee, I agreed to his stipulations.

‘Last evening, therefore, at seven o’clock, nine members of the Society, including the two of us, assembled in the Experimental Annexe at my house, along with Mr Kellway and a couple of attendants. We all observed as the experimental materials were placed in Room B, the middle room. I locked the door, leaving the light on. The table and closed box were clearly visible through the glass of the door. At half-past seven, with Venus twenty minutes away from setting by the almanac, Kellway entered the unlit Room A. Again I locked him in myself. Room C was to play no part in the experiment and was never unlocked, or for that matter lit.

‘Kellway took off his shoes and jacket and began his meditations. We could see him dimly in the light from the antechamber, sitting in what is called the lotus position. From the moment I turned the key he could not have escaped the room by normal means – he would have needed to slither under the door or float through solid brick. Even the window was locked shut, it being a cold night.

‘At eight o’clock, as we had arranged, we all left the room except the first pair of observers. Our standard practice for protracted sessions such as these is that Rhyne here, who serves as secretary to the Committee, draws up a rota of such observers. As I say, it is less usual for such events to occur overnight, but fortunately my house is large and I have no family, so my staff were able to arrange accommodation for those who needed it.

‘The reason for using two observers at a time is of course to reduce the risk of human error or collusion with the subject. As a general rule in such cases, the observers are not constantly peering through the glass at the subject, as naturally this tends to distract them. Our normal approach is that the observers look through the doors at timed intervals of five minutes, one checking on the subject while the other confirms the status of the experimental materials. Nobody enters the rooms, of course – they remain locked.

‘On this occasion the first two observers were Dr Peter Kingsley – a gentleman of your profession, Dr Watson, who is my neighbour in Richmond – and Professor Elias Scaverson, one of our more distinguished scientific members. Between observations they spent most of the time playing cribbage, and they reported nothing unusual or amiss. At ten o’clock Rhyne here relieved them, along with Major Bradbury; and so we continued throughout the night, with pairs of individuals taking two-hour shifts, until the four to six o’clock shift this morning.

‘The observers at that time were Frederick Garforth, the artist, and my butler, Anderton. Unlike myself and Rhyne, Anderton is an honorary rather than a full member of the Society, as, if truth be told, he has little interest in scientific matters, but he has helped make up our numbers on several past occasions, and I would trust him as an impartial observer above a number of our regular members. At a little before ten to five Major Bradbury, having woken early in a companionable mood, joined them once again. At ten minutes to five, five to five and five o’clock, Garforth and Anderton looked into the rooms as usual and saw, as before, the box sitting undisturbed upon the table in Room B, and Kellway meditating with great concentration in Room A.

‘At five minutes past five they checked again, and Garforth cried out that Kellway had vanished. Bradbury and Anderton immediately checked his observation and confirmed it. Thomas Kellway had disappeared, Mr Holmes, from a locked room, leaving behind him not a trace of his passing.’

Schedule and Plan for an Experimental Test of TelekinesisThe Psychic Experimental Annexe, Parapluvium House,14th & 15th September 1896

SUBJECT: Thos. Kellway

SCHEDULE:

7 p.m. to 8 p.m. START OF EXPERIMENT.

Setting-Up and Locking of Experiment Rooms. All Society Members welcome to attend. NB: Venus sets 7.49 p.m.

8 p.m. to 10 p.m. FIRST OBSERVATION:

Dr Kingsley, Prof. Scaverson.

10 p.m. to 12 p.m. SECOND OBSERVATION:

Major Bradbury, Mr Rhyne.

12 p.m. to 2 a.m. THIRD OBSERVATION:

Revd Small, Mr Beech.

2 a.m. to 4 a.m. FOURTH OBSERVATION:

Lord Jermaine, Mr McInnery.

4 a.m. to 6 a.m. FIFTH OBSERVATION:

Mr Garforth, Wm. Anderton.

6 a.m. to 8 a.m. SIXTH OBSERVATION:

Sir Newnham Speight, Hon. Mr Floke.

8 a.m. onwards END OF EXPERIMENT.

Release of Mr Kellway, followed by Breakfast and Discussion of Results. All Society Members welcome to attend.

CHAPTER TWO

I whistled, and Holmes, who had been listening intently throughout all of this, was equally impressed. He said, ‘I had hopes that you were leading up to some spectacular revelation, Sir Newnham, and you have not disappointed me. Please tell us the rest. What happened next?’

‘Well,’ said Speight. ‘After Bradbury and Anderton had reassured Garforth that his eyes were not deceiving him, Anderton came to find me at once.

‘I was already awake and mostly dressed, as I was to take the sixth and final shift. I sent Anderton to knock up Rhyne, and went down to the Annexe straight away. I would have been there by ten past five. Bradbury and Garforth were waiting for us in the anteroom, and had nothing new to report. When we arrived I unlocked the door to Room A and the three of us searched it together – not that there’s anywhere in that bare space where Kellway could possibly have concealed himself. We also checked on Room B, but found the billiard ball still inside the box.’

‘Did you check the third room?’ Holmes asked.

‘For form’s sake, yes. It was perfectly empty. There are also some cupboards in the anteroom where experimental equipment is stored, and when Rhyne joined us he suggested searching those as well, in case Kellway had somehow… Well, we were all at a loss for an explanation, and by now I’m afraid we were clutching at straws. Nothing had been disturbed in any case, and of course there was no sign of Kellway.

‘We roused the rest of the household, and assembled the Society members in the Experimental Annexe. Nobody could explain how Kellway had left a room that was, for all reasonable purposes, sealed tight, nor where he might be now. Of course, by that I mean that nobody was able to offer a conventional explanation. Inevitably, several of those present were inclined to take a supernatural view of the affair.

‘For my own part I am sceptical enough to believe for now that this is an unprecedented hoax, though as to its mechanics I am just as much perplexed as everybody else. In fact I have been half-expecting Kellway to stroll in and claim the reward, but when I left Richmond this afternoon he had not yet reappeared.

‘This, then, is the problem I came to put before you, Mr Holmes. How did Thomas Kellway escape from that room, where is he now, and does the Society for the Scientific Investigation of Psychical Phenomena owe him ten thousand pounds?’

‘A most attractive problem, indeed,’ Holmes said. ‘Although I fear the possibilities that Mr Rhyne outlined at first are extreme ones. If Kellway has indeed vanished away, there is no more reason to suppose him on Venus than anywhere else – indeed, I venture to suggest that the feat of transporting oneself instantaneously and intangibly from one place to another would be no less marvellous if one’s destination were Putney Common. And if Kellway is a hoaxer, I venture that he is more liable to prove a talented practitioner than an unprecedented genius, though I admit the effect he has produced is an exceptional one.

‘I have a few questions, Sir Newnham, if I may. To begin with, where were the keys to the Experiment Rooms kept during the procedure? I mean the keys to the windows as well as the doors.’

‘My housekeeper, Mrs Catton, keeps one set,’ Speight said, ‘which she is meticulous in locking away when they are out of use. The other was on my key-chain, which I keep on my person. When the Annexe is not in use, that set remains in the safe in my study, to which only Rhyne and myself have the combination. The windows all use the same key, and that is on a ring with the three door-keys.’

‘Was your key-chain on your person while you were asleep?’ Holmes asked, somewhat sceptically.

‘No – it was not, of course,’ agreed Sir Newnham. ‘It was on my night-stand in my room – I always place it there at night, and I remember seizing it in haste on my way down to the Annexe. It was, however, within two feet of me, and I am an unusually light sleeper, as my manservant will be able to confirm. I tend to wake several times during the night, and last night was no exception. I cannot see that anyone could have entered my room and borrowed the chain without my being aware of it.’

Holmes proceeded with his questioning. ‘You said that the experiment rooms were empty other than Kellway and the table, box and ball, but you then told us that Kellway took his shoes and jacket in with him. Precisely, please, what was in Room A?’

‘Precisely? Well, Kellway himself, of course. The light bulb and a coat-hook are the only fixtures. Normally we provide a chair for the subjects, but Kellway insisted he had no need of that. He took in the clothes he was wearing, naturally, including his jacket and shoes. I believe he also had with him a walking-cane.’

‘What was in his jacket?’ I asked.

‘A highly pertinent point,’ said Holmes. ‘I trust that you at least searched his pockets for suspicious items.’

‘We do so as a matter of routine,’ Sir Newnham said, seeming a little hurt. ‘As I said, we have been troubled by pranksters in the past. I don’t believe we found anything out of the ordinary, though. What did he have on him, Rhyne?’

His secretary said, ‘A pocket book containing cards and notes, some loose change, a handkerchief, a door-key. That’s all.’

‘No cigarettes or tobacco?’ Holmes asked. ‘No matches?’

‘Kellway’s a strict non-smoker,’ Rhyne said. ‘It’s one of his fads. But, gentlemen, if you know of something a chap could hide in his clothes that would let him disappear from a locked room – or to move an object in an adjacent room, for that matter, since that’s what we were expecting – I’ll be astonished to hear of it.’

Holmes nodded thoughtfully. ‘I will need to examine the items even so, assuming they are still in his jacket. I take it he spent the night in shirtsleeves and socks?’

‘He took off his socks as well,’ said Rhyne. ‘I didn’t see him do it, but he was certainly meditating barefoot by the time I came on watch.’

‘You said that one reason for pairing observers together was to prevent collusion,’ Holmes said to Speight. ‘But it is surely conceivable that two men might collude together with a third.’

‘I said it reduced the risk,’ Sir Newnham corrected him. ‘It is impossible to rule it out altogether. We do our best to avoid pairing together relatives, business partners or close friends. In this instance, of course, Major Bradbury was unexpectedly also present at the time of the disappearance. Of course many of our members come to know one another through the Society itself, but I know of no particular connection between Bradbury and Garforth, and I most certainly trust Anderton. He has been with me for nearly thirty years, first as my manservant and then as my butler, and is an intelligent man of shrewd judgement and great loyalty.’

‘And Garforth and Bradbury? What can you tell us of them?’

‘Both good men, as far as my knowledge goes,’ Speight said. ‘Major Bradbury I have known since he retired from service in India, seven years ago. He’s quite the enthusiast for Eastern religion, but keeps a level head in everyday matters, though I believe he was quite charmed by Kellway. Garforth has been with the Society for a year or so. I don’t know him as well as the others, but I believe he’s a friend of Rhyne’s family.’

‘Oh yes, I’ve known Garforth since I was a boy,’ Rhyne confirmed, in his boyish tones. ‘I called him Uncle Freddie as a lad. He’s a very sound fellow.’

‘You stood Major Bradbury’s own watch with him, Mr Rhyne,’ Holmes said. ‘Did he strike you as especially interested in Kellway at the time?’

‘Well, not especially,’ the young secretary said. ‘He takes an interest in all our subjects – he seems to have seen a lot of mystical stuff that impressed him out in India, and he lives in hopes of seeing the same thing reproduced scientifically here. I’m not surprised he was interested in how things were proceeding, come the morning.’

‘And what did you make of Kellway?’ I asked him. Rhyne hesitated.

‘You may as well tell them, Rhyne,’ Sir Newnham said with a sigh. ‘You know I can’t stand intellectual dishonesty.’

‘Well.’ Rhyne shrugged. ‘He’s a remarkable fellow, forceful and charismatic. I’m not so fond of his esoteric cosmology; as Sir Newnham says, it’s more like some superstitious hangover from medieval astrology than anything scientific. But it’s not so hard to believe that, if anyone had extraordinary mental powers, it would be a man like Kellway. And… well, look, a chap doesn’t just disappear, not in the natural course of events. As you say, it’s not so very important whether he went to Venus, just that he went somewhere – and, to be frank, I believe he did. He might be waiting for the right conditions for his return, or… well, he might not even have survived the journey. Or the destination, if it were the South Pole or the bottom of the ocean. He might not have had control of the process, you see.’

Sir Newnham sighed expressively. ‘And there you have it – Rhyne is a rational man, or I would never have employed him as my secretary, and he is convinced. Oh, don’t fret, Rhyne, I don’t take it personally. Mr Holmes, I don’t care at all about the money – ten thousand’s nothing to me. But if we hand Kellway the reward and he turns out to be a fraud, the Society will become a laughing-stock and my reputation will be ruined. I am not just an inventor, Mr Holmes, I am a scientist, and I rely on my standing among others of that profession. It would be a grave blow to me, a grave blow indeed.’

Holmes said, ‘If Kellway should reappear to claim the reward, how will the matter be decided?’

‘The Society Committee must agree it. That’s myself, Dr Kingsley as Vice-Chairman, Professor Scaverson, the Reverend Small, the Honourable Gerald Floke and the Countess Irina Brusilova – and Mr Gideon Beech, who is our Treasurer. Rhyne acts as secretary to the Committee but does not have a vote.’

‘Gideon Beech?’ I asked in surprise. ‘The playwright?’ The author of a number of scandalous plays that had outraged the morals of society, Beech was considered an enfant terrible of the theatre; but he had also been canny enough to write The Man for Wisdom, a popular light comedy that had won him financial success and acclaim from the masses of less highbrow theatregoers who remained untroubled by his more challenging works. Beech was forever penning articles and letters to the press, their primary subject, whatever their ostensible topic, always seeming to be himself. From them I knew that he was a ferocious Fabian, a teetotaller, an advocate of spelling reform and numerous other enthusiasms, but this was the first I had heard of his having more esoteric leanings.

Speight nodded. ‘He was one of our earliest members, as a matter of fact. As I was saying, I would call an extraordinary meeting of the Committee and there would be a vote on the matter. As Chairman, I would only cast my own vote in the event of a tie. In the current situation, I’m not sure I would get the chance. Floke is young and rather impressionable, and admires Kellway greatly. The Countess is an inveterate advocate of outlandish phenomena of all kinds, so I fear she would take little persuasion to go along with him. And Kellway’s cosmic mumbo-jumbo has a very particular appeal to Beech, as it supports his own idiosyncratic views on evolution. Beech won’t hear a word against him, in fact. Since this morning he’s been quite convinced the wretched man has been spirited away to Venus.’

‘Much, then, would depend on the votes of Professor Scaverson, the Reverend Small and Dr Kingsley,’ Holmes observed.

‘Indeed,’ agreed Speight. ‘Kingsley and Scaverson are men of science, and reliable. But Mr Small is not only a believer in the supernatural by profession, but a man of a rather… individual bent. I understand some of his own parishioners view him as a troublemaker, in fact. I fear that Small might vote to endorse Kellway purely for his own amusement, and that would be the Committee won over.’

‘Well, I shall hope to speak to them all in due course,’ said Holmes. ‘In the meantime you may perhaps take comfort in the fact that Kellway has not yet reappeared to cash in on his remarkable coup de théâtre. Sir Newnham, if I accept this case, it will be with one stipulation. My primary interest will be in establishing how this person vanished, and you may decide about the reward accordingly. His current whereabouts, unless they prove germane to his method, will be of lesser importance to me.’

‘Well, I won’t object to that,’ Sir Newnham said. ‘I hope the fellow’s safe, of course, but I admit it would spare us some trouble if we never saw him again. My hope, though, is that you will uncover the truth, whatever it may be.’

‘What’s your view of the case, Mr Holmes?’ Talbot Rhyne asked.

‘I always try to avoid theorising without sufficient data, Mr Rhyne. I hope to have a clearer picture once I have inspected the scene of the disappearance itself. I fear I have some business to attend to this evening which cannot wait, but if you are agreeable, Sir Newnham, Watson and I will call upon you in the morning.’

‘Of course, Mr Holmes,’ said Speight. ‘But, like Rhyne, I’d appreciate hearing any thoughts you may have at this point, however unformed.’

Holmes sighed. ‘At present I have little beyond the obvious. You tell me that Kellway was visible in the room at five o’clock, and visibly absent five minutes later, and that in the meantime he could neither have hidden himself in the room nor left it by natural means. As it is unlikely that Kellway has performed a feat that all prior scientific thought tells us is impossible, my first hypothesis must be that you are mistaken in some aspect of the story you have presented to me.

‘I hope to make my own assessment of the escapability of the room when I inspect it tomorrow, but if what you have told me holds then I shall be left with the likelihood that you have been lied to. Several witnesses including yourself saw Kellway enter the room and stay there; multiple pairs of observers testify to his presence throughout the night; and you affirm that you found him absent from the locked room at ten past five. Since I have no choice but to trust your own account, the point where the story is weakest is at the time when Garforth, Bradbury and Anderton attest that the vanishing took place, and you have their word alone for what happened.

‘The case thus becomes a question of conspiracy to defraud, involving a mere picked lock or copied key, rather than anything supernatural. Our working hypothesis must be that these three witnesses colluded to let Kellway escape, and all of them have lied to you about it.’

But the great inventor had been shaking his head for some time. Now he said, ‘I’ve read Dr Watson’s case-studies, sir, and I’m familiar with your maxim about eliminating the truly impossible and accepting any remaining improbabilities. But to apply it, one must first draw the line between the impossible and the improbable, and where that line lies can be partly a matter of personal judgement. I don’t know Garforth well, and I could perhaps believe that Bradbury had somehow been compromised, but Anderton is as loyal to me as my right arm. I have known him since we were boys. If he needed money, or were being blackmailed, or compelled in any way, I am certain he would have come to me at once.

‘It seems to me, Mr Holmes, that your dictum fails to account for different types of impossibility. I might well be persuaded that the continuum of phenomena allowed for by our current science is incomplete, but I could never believe that William Anderton would conspire to defraud me.’

Holmes nodded. ‘I had rather supposed that you might say that. It certainly serves to make the case more interesting,’ he said. ‘Good evening, gentlemen, and I look forward to furthering our acquaintance on the morrow.’

The Chiswick Weekly Parish Examiner

Friday 7th August 1896