Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

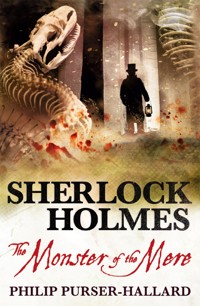

When Watson's holiday in the Lake District takes a sinister twist, he and Holmes must uncover the truth hidden by superstitious locals, folklore and rumours of prehistorical monsters far away from the familiar streets of London... A serene walking holiday in the Lake District becomes a far more sinister excursion for Dr Watson when disappearances and murders start occurring in the small town of Wermeholt. Local legends, rumours of large slithering reptiles and spooked palaeontologists have the denizens paranoid and terrified, so it is up to Watson and his inbound companion Sherlock Holmes to uncover the truth and discover what is really lurking in the lake…

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 389

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Author’s Note

About the Author

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Sherlock Holmes:Cry of the InnocentsCavan Scott

Sherlock Holmes:The Patchwork DevilCavan Scott

Sherlock Holmes:The Labyrinth of DeathJames Lovegrove

Sherlock Holmes:The Thinking EngineJames Lovegrove

Sherlock Holmes:Gods of WarJames Lovegrove

Sherlock Holmes:The Stuff of NightmaresJames Lovegrove

Sherlock Holmes:The Spirit BoxGeorge Mann

Sherlock Holmes:The Will of the DeadGeorge Mann

Sherlock Holmes:The Breath of GodGuy Adams

Sherlock Holmes:The Army of Doctor MoreauGuy Adams

Sherlock Holmes:A Betrayal in BloodMark A. Latham

Sherlock Holmes:The Legacy of DeedsNick Kyme

Sherlock Holmes:The Red TowerMark A. Latham

Sherlock Holmes:The Vanishing ManPhilip Purser-Hallard

Sherlock Holmes:The Spider’s WebPhilip Purser-Hallard

Sherlock Holmes:Masters of LiesPhilip Purser-Hallard

Sherlock Holmes:The Back-to-Front MurderTim Major

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Sherlock Holmes: The Monster of the Mere

Print edition ISBN: 9781789099263

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789099270

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: May 2023

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2023 Philip Purser-Hallard. All rights reserved.

Philip Purser-Hallard asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

CHAPTER ONE

In June of 1899 I was engaged in a walking tour of the Lake District, that unlikely pocket of alpine territory hidden away in the far north-western corner of our English countryside. As I wandered the landscape walked before me by shepherds and poets, the serenity and grandeur of its vistas reminded me of my visit some years previously to Switzerland. That earlier journey had brought with it considerable trials, culminating in what I had believed at the time – erroneously, thank Heavens – to be the tragic death of my friend, Sherlock Holmes, at the hands of Professor Moriarty. On this occasion, I had more restful company in the person of my schoolfriend Percy Phelps, with whom I spent a pleasant time interspersing energetic walks with convivial interludes in inns and hostelries.

As we reached the town of Ravensfoot on the northern shores of Lake Wermewater, Phelps received word of a minor family emergency and was forced to cut short our sojourn. Resolving to persevere alone, I bade him farewell at Ravensfoot railway station, and continued in solitary progress around the lake’s shore until I neared Wermeholt, the smaller town facing Ravensfoot across the waters from the south.

Murray’s Westmorland, Cumberland, and the Lakes had promised me a fine walk from there up to the summit of Netherfell, from which a panorama of Wermewater and the neighbouring peaks would be visible. I was to spend the afternoon of Thursday the fifteenth exploring Wermeholt, and intended to stay there for the night before walking the recommended path on the morrow. From Netherfell’s heights I should make my way down to Hartsmere, reaching the town of Hartsdale by Friday evening.

The locals in Ravensfoot had warned me to make my way westward around the lake, as much of the eastern shore belonged to the Wermeston family and was closed to the public, and so I approached Wermeholt with the fell to my right, and the morning sun glinting from the lake before me. A large wooded islet, Glissenholm according to my map, interrupted its waters like the pupil of an eye, and I reflected on that peculiarity of local dialect, inherited from our Celtic forebears, that transforms the lakes in this part of England into meres, its mountains into fells, its streams into becks and its islands, amusingly to me, into holms.

From Ravensfoot, Wermeholt had seemed a pretty enough place, nestled beneath the slopes of the fell, but as I commenced the downward approach towards the town, it came to seem less picturesque. I had not appreciated quite how overshadowed it would be by Netherfell; only now, at mid-morning, was the town beginning to welcome the sun’s illumination. Like many settlements in the area, Wermeholt was built mainly from the local black slate, but few of its buildings boasted the cheerful white limewash that brightens many of those in the more popular wayside stops. Some way beyond the town, a tall spur of rock stretched out from the fell almost to the side of the lake, its nearer slope scarred and grey.

I paused at a fork in the path, one track leading up towards Netherfell’s summit, the other the route that would take me down past the lakeside to Wermeholt. An ornate way-marker stood at the divide, carved from some dark stone.

I peered north across the lake towards the friendlier waterfront of Ravensfoot. A train, the first since Phelps’ departure, was approaching the town around the base of Ravensfell, and I heard the distant note of its whistle, as puffs of steam sketched a line across the side of that further slope. To the south, Wermeholt glowered at me like the town’s dark reflection, an impression amplified by the shadowed peak above.

I considered simply continuing up the fell and so on to Hartsmere, arriving at my next destination a day early. It would make for a long day’s walk, though, with no opportunity for luncheon or other refreshment, and so I resolved to adhere to my original itinerary.

I strode on into the gloom, through meadows cropped and fouled by sheep and demarcated with drystone walls, and shortly found myself in a grey, unlovely high street. A churchyard with a stone church tower lay close by the shore, and along the street a dilapidated pub sign proclaimed a dilapidated pub. A grey dog of indeterminate breed was tethered outside the latter, and it stirred fretfully and whined at me as I approached. I patted and complimented it before moving on. Between an ironmongery and a butcher’s shop bearing the name F.H. BATTERBY stood a grocery-cum-post-office, and I considered whether, in Phelps’ absence, I should write to Holmes suggesting he come up and join me in my meanderings.

I feared, though, that without the mental stimulation of the criminal cases that normally brought us to such far-flung regions, he would simply find them dull. When I had first proposed such a tour he demurred, pleading an inseparable attachment to the pavements and byways of London that had for so long constituted his native domain.

“Come now, Holmes,” I had cajoled him. “You have not had a holiday for ages. It will do you good to get out of the city. A change is as good as a rest, you know.”

He smiled. “Ah, but I prefer to take my rest in familiar territory. The atrocities of the countryside have their charms, to be sure,” he conceded jovially, “and I have no doubt that I shall sample them again. But, for the present, I prefer the more comfortable crimes of our fair metropolis.”

And so I had instead spent a week in restful companionship with Phelps, a more peaceable traveller, and if I had found his talk of his young family and modestly distinguished career at the Foreign Office somewhat lacking in excitement, he compensated for it with a tolerance for late mornings and idle lunches that I have yet to discover among Holmes’s admirable qualities. When Phelps had been summoned home to Woking, I too had considered hastening back to the old shared rooms in Baker Street, but I found myself too enchanted by the majesty of my surroundings to give up on my planned peregrinations.

Wermeholt did not, on its showing so far, live up to the promise of its surroundings. Still, while not perhaps the most idyllic haven the Lake District had to offer, it was to be my resting-place for but a night, and I resolved that I should make the best of it. Having ascertained the location of the Mereside Hotel, where I purposed to stay, I turned back along the high street and returned to the church of St Michael the Archangel to pursue my plan for exploration. Returning the rather indifferent nod of a woman walking home carrying her groceries, I entered the churchyard and strolled around it, inspecting its slate roof and battlemented bell-tower.

Like many of the older churches in the area, St Michael’s was sturdy and squat, as if constructed for defence rather than worship. The graveyard, crowded with centuries of the dead, stretched all the way to the lakeside, where a crumbling stone wall shored it up, for now at least, against a collapse into the mere. A gate there gave onto some steps, which led down to a wooden jetty.

The church door stood open to visitors, so I doffed my hat and stepped inside.

The inner walls were as rough as the exterior, and windows of plain glass failed to make much of the pitiful sunlight. Though inevitably lacking the grandeur of our city churches, the edifice nonetheless conveyed a simple honesty of faith that would, or so I endeavoured to convince myself, impress the folk of so humble a town.

The church’s only notable decoration stood in the vestibule: a statue, perhaps three feet tall, of its patron saint engaged in energetic combat with Satan in the form of a dragon. It was executed in the same dark volcanic stone as the way-marker I had seen earlier, and perhaps by the same sculptor, as that had been in the shape of a globe held in a dragon’s foot. St George’s Church in Ravensfoot had, I recalled, made similar use of a scene from the legends of its own patron, but that building was a relatively modern one, and its statue had been tame in comparison. This sculptor had made his sainted angel stern and warriorlike in his armour, but his devil was truly terrifying – its snout abrim with teeth, its wings leathery and clawed, its coils constricting the saint as if they would snap him in two.

“A vivid vision of evil, is it not?” a man’s voice observed, close behind me, and I started. Turning quickly, I found a man in clerical garb, his face becoming apologetic as he beheld my surprise.

“It is,” I said, recovering myself.

“Is it very old?” “I believe it dates back to the sixteen-hundreds. But I apologise, sir,” the priest added nervously. “I had no intention of startling you. You were quite absorbed in your contemplation, and did not hear me approach. I share your fascination with this piece. You will find that it continues to haunt the imagination long after it is first seen. My name is Felspar, sir, the Reverend Gervaise Felspar, and I am the vicar here.”

“I am Dr John Watson,” I told him. “I am pleased to meet you, sir. My walking companion left me this morning, and I am now roving alone wherever my Murray’s chooses to take me.”

“You have chosen your destination well, Doctor,” Mr Felspar replied. “This is a most lovely part of the country. I am no native, and to the good-humoured scorn of my parishioners I cannot abide boats, but nevertheless I have come to consider it my home.”

While he was correct about the loveliness of the Lakes as a whole, I found it difficult to concur regarding Wermeholt, at least on the basis of what I had seen so far. I made some noncommittal response.

After his initial forwardness, Felspar seemed rather a timid soul, and was clearly pleased that I had not taken offence at his intrusion. He told me that he had been the incumbent at Wermeholt for some six years, having moved from a parish somewhere in the Midlands. “An honest people,” was how he described his current parishioners, “though superstitious at times, and set in their rustic ways. My parish houses perhaps a hundred souls, and I serve them as best I may.”

He told me that the churchyard was unusual in having two lych-gates, or corpse-gates as they are called in those parts – one approached in the normal way by a lych-path from the road, and the other giving on to the jetty, where the inhabitants of Ravensfoot had once been wont to deliver their dead by barge for burial in St Michael’s churchyard. “There was a time,” Felspar said, “when Ravensfoot was a mere hamlet, and Wermeholt the largest settlement for many miles. The Ravensfoot slate mine changed that. We have no comparable industry on this side of the mere. That is why the railway passes instead along the northern shore.”

He confirmed that the inn I had seen earlier would provide me with lunch, and as the church clock struck twelve I pleaded the demands of my stomach and left him to his devotions. In truth I was looking forward to some hearty refreshment after my morning’s exertion.

As I stepped outside the church, I saw that the woman I had seen earlier was still positioned across the road, groceries now at her feet. She was speaking animatedly in the local dialect to a younger woman, who was stoically ignoring the complaints of a small child tugging at her hand. As I emerged from the churchyard, the older woman turned to glance at me before returning her attention to her friend. Her face was grey and craggy, and she wore widow’s black.

Outside the hostelry I found the grey dog I had met earlier untied, and lying at the feet of a muscular man who sat on a bench, smoking a pipe and seemingly guarding the entrance. The sign above him was a dilapidated representation of a coat of arms, presumably that of the local landowner. The seated man nodded curtly, as if granting me permission to enter. The wag of the dog’s tail was friendlier.

Inside, I found the building in poor repair, with peeling paint and a pervading smell of damp. However, the barmaid was pretty enough, and willing to sell me a pint of adequate porter, which will endear me more closely to anyone. With a promised mutton pie to follow, I soon cheered up, and settled myself at a rickety table with my mug of beer. I leaned my walking-stick against the wall, took my writing materials from my haversack, and began a letter to Holmes while I awaited my food. I had used the last of my stamps in Ravensfoot, but doubtless the Wermeholt post office would oblige.

“Is thou – are you up from London, sir?” said the girl when she brought me my pie with peas and potatoes. “I thinks thou – you must be, from your accent. I hope you don’t mind me asking,” she went on. Her own accent was strong, but after a week spent in the region I found it easier to follow. “I like to know where our visitors come from. My da and me don’t get away from Wermeholt over often, with t’pub to run. Over til Ravensfoot for market days is all, and once two year ago til Keswick, for my cousin’s wedding there. But we get a lot of folk from other places coming through, and I like to meet them. I’s – I’m Effie, sir, Effie Scorpe. My da Ben’s t’publican here. My auntie does t’cooking for t’pub, but it’s just him and me lives here since my ma died.”

“Well, I am pleased to meet you, Effie,” I told her, though a little warily. She was pretty, as I have said, and young, with a freckled face and hair all curls, and while there was no sign of any other presence behind the bar, I did not wish her father to overhear us and conclude that I was being overfamiliar. “I am Dr Watson, I am indeed from London, and I’m on a walking tour of the Lakes.”

“Lots of gentlemen comes here for t’walking,” she agreed with me eagerly. “They say travel broadens t’mind, sir, and perhaps talking to travellers does t’same, for those of us stays in one place. London’s a fearful long way, I ken, and so big – a town bigger than any of our lakes, they say, though I can scarce believe that.”

“Effie,” I said, “Regent’s Park, close by where I live in London, is perhaps half the size of Wermewater by itself. It’s the tiniest scrap of green in the smoggy grey sprawl of the capital.”

“Now I ken thou’s joking wi’ me, sir,” said Effie Scorpe, forgetting her careful grammar. She affected a scornful expression, but I could see the excitement in her eyes.

“It’s absolutely true,” I told her. “Perhaps one day you’ll see it for yourself.”

“Stop pestering t’gentleman, Effie, and gan thou back til t’bar. Let him eat his dinner in quiet.” The rough voice belonged to the surly, burly man from outside, who had returned. Though his face was certainly not one that I would have described as pretty, now that I saw them together I could detect a certain resemblance.

“Mr Scorpe, I presume,” I said apologetically. “It’s my fault, I’m afraid. I’ve been keeping your daughter from her duties. I’ve been walking alone all morning, and welcomed the conversation.”

“That’s as maybe,” Ben Scorpe grunted, ushering Effie back to the bar nevertheless. “She has her work.”

I finished my lunch in a less convivial mood, reluctant even to ask for my mug to be refilled lest I get my young friend into further trouble with her father. However, as I left with my completed missive, I asked her whether I would find the post office open, and she confirmed that I should. “Don’t get talking to Mrs Trice, though,” she warned me with a smile. “She’ll have your business all over town afore sundown.”

Thanking her for her help, and nodding a cordial farewell to her father, which he acknowledged reluctantly, I left the inn and walked up the street to the premises I had observed earlier. Rather than anything the average Londoner would recognise as a post office, this turned out to be a village shop with shelves displaying everything from carbolic soap to mustard powder, a row of bottles containing tinctures of variously dubious medical efficacy, and a counter for taking parcels and telegrams. It was adequate to my purposes, nevertheless.

The lady in charge proved as loquacious as Effie had promised me on the subject of visitors to the town, and just as fascinated by my own affairs. She even opened our conversation with the same question. “Are you up from London, then, sir?” she asked me with keen interest. She was in late middle age, with a peevish look behind her half-moon spectacles and an ingratiating manner. When I told her my name, she added, “Are you with those scientists at t’Mereside?”

“Scientists?” I asked. It seemed an unlikely spot for a scientific project, but perhaps there were some experiments that might best be conducted in such an isolated area as this. “How many are they?” I had merely checked the position of the Mereside Hotel earlier, not considering that it might already be full. Again I wondered whether I could manage the walk to Hartsdale that afternoon, should it prove necessary.

“Four of them,” said Mrs Trice promptly, “and a lady. Two older gentlemen and two younger. Friends of Sir Howard Woodwose, they are.”

“I see.” From what I had observed, the hotel was surely more than large enough to accommodate such a group and myself. “No, I’m not of their party. I’m a medical man, here on holiday. Isn’t Sir Howard Woodwose a student of folklore, though, not a scientist?” I had seen the name in newspapers, mentioned in connection with the study of such things as medieval ballads, fairy tales and the legends of Robin Hood. While I knew little of such matters, I understood that his books were well thought of by those better versed than I.

“Oh, he knows about all kinds of things, Sir Howard does,” said Mrs Trice. “A fearfully learned man, they say. Oh!” she remarked, for at this point she glanced down at the envelope that I had carelessly placed on the counter. “I see you’re writing to Mr Sherlock Holmes, in London. Would he be a friend of yours, then, sir?”

I realised that I should have anticipated her interest, and cursed myself. Since most of those who write to Holmes are seeking his assistance with some mystery, criminal or otherwise, I was a little surprised that she had jumped to the conclusion that we were acquainted, but perhaps she simply assumed that everyone in London knew everyone else.

“As it happens, he is,” I replied. As Effie had warned me, this busybody would doubtless broadcast my affairs to all and sundry before the day was out. Still, I did not suppose I could prevent that by dissembling now.

“Then you must be the Dr Watson that writes t’stories!” she declared, her eyes alight with gossip’s glee. “I dare say you’ll have a great many tales to tell us, then.”

“I have told most of them,” I assured her, allowing myself considerable latitude from the truth, “in my stories for the magazines. If you have read them, then you know already virtually all that is of interest.”

“Read them?” She frowned, as if the suggestion were indelicate. “No, I can’t say I’ve read them. But I’m sure we’re pleased to have you here, Dr Watson. Tell me” – and I was able to predict with absolute accuracy what her next words would be – “will Mr Holmes be joining you? It’d be an honour for us in Wermeholt to welcome a man of such distinction. Perhaps there’s some matter he sent you ahead to investigate?” she added insinuatingly.

I sighed. “No, Mrs Trice, I’m afraid I really am here on holiday, and Mr Holmes has no plans to join me. He is very busy with affairs in London at present.” I tried to change the subject. “I’m more interested in these scientists you mentioned, Sir Howard’s friends. Do you know what their purpose is in coming here?”

But my reticence had perhaps offended the postmistress. “I wouldn’t know anything about that, sir. You’d have to speak to them.”

I bade her a hasty good day and left the shop, pausing only to place my stamped letter into the box outside. Though I had little confidence in its privacy, given the hungry way Mrs Trice had been eyeing it, its contents were innocuous, and I did not care to carry it all the way to the post office in Hartsdale.

As I left the post office, I was surprised to see the craggy-faced widow for the third time, this time without her groceries, but once again glancing at me, with a curt nod of acknowledgement, from across the road. I was sure that, when I had first seen her outside the church, she had been heading in the opposite direction.

CHAPTER TWO

Although it was but early afternoon, the sun was vanishing already behind the western slopes of the fell. In view of the information I had just received, I felt that I had better proceed to the Mereside Hotel and secure a room for the night. There had been no other walkers on the trail from Ravensfoot that morning, but others could have set out later, or have approached the town the other way, from Hartsdale.

Accordingly I presented myself at the Mereside, and was rewarded with a serviceable enough room. “It’s all we have,” the proprietor told me. A melancholy man named Mr Dormer, he spoke with a mild local accent, lacking the telltale signs of dialect that Effie Scorpe had been struggling to shake. “We’ve a party taking up the rest. No view of the water, I’m afraid. You’re welcome to it if it serves.”

I agreed that it would, and took up residence therein. As my host had warned me, the window looked back along the length of the high street towards the church, with little visible of the promised lakeshore. The prospect was entirely overshadowed by the fell. I washed and unpacked my haversack, then took my guidebook downstairs to a gloomy sitting-room, intending to make notes on prospective sights in Hartsdale and points beyond. My aim was to finish my tour at Ullswater, and to return home to Baker Street before the month was out.

The lounge was somewhat threadbare, with a fireplace that might have been cosy in winter but on a summer’s afternoon seemed dismally superfluous. Shabby tapestry sofas and armchairs promised a little comfort, and a picture window gave a view across the garden to the lakeshore, with Glissenholm and Ravensfell beyond. Beneath the far hill’s slopes, Ravensfoot gleamed in sunshine above serene waters, a glimpse of a better world.

As I was taking all this in, to my surprise a tall, gaunt figure sprang up from one of the armchairs, took the briar pipe from his mouth and calmly stated my name. “Dr Watson.”

For a moment my heart leapt, thinking that Holmes had changed his mind about a holiday together and had thought to surprise me here, but this man was not he. It took me a moment to place him.

“Dr Summerlee?” I said. “Summerlee, the anatomist?” He had been a junior lecturer at my medical school, and had instructed me sternly on the inferences to be drawn by comparisons between human and animal skeletons and organs. Though I admired his fierce intellect, I had never found him congenial company.

“I am Professor Summerlee now,” he told me, shaking my hand. “I hold the Chair of Comparative Anatomy at University College.”

It had easily been twenty years since I had last seen Summerlee, whose austere and precise manner had, despite his absolute adherence to scientific rationalism, earned him the nickname “the Jesuit” among his students. Though he was but a few years older than myself, his familiar goatee and moustache had gone quite grey. As ever, he carried about him a mingled smell of stale tobacco-smoke and other odours that suggested he had not washed for several days.

“I have been following your own work with interest,” he told me. “I do not mean your medical career, which I understand is undistinguished, but your popular publications. Your accounts of Mr Holmes’s exploits are sensationalised, inevitably, but I find the records of his deductive technique and accomplishments to be inspiring.”

“He would be gratified to hear it,” I told him. It was in keeping with Summerlee’s personality that what he most appreciated about my writing was the abstract intellectual theory Holmes himself was always encouraging me to emphasise, to my publishers’ despair. “Personally I enjoy the sensational events and details. They’re indispensable when selling the stories to publishers and readers.”

Summerlee nodded. “As I said, such trivialities are inevitable. For my part I am not averse to adventure, but it is a means to scientific enquiry, not an end in itself.” I recalled being told that as a younger man he had joined a number of expeditions, both zoological and anthropological, to various uncivilised climes, and had returned professing a thorough indifference to his experiences, though never to the knowledge he had acquired by them.

“I say, Professor,” I said, “I suppose you must be a friend of Sir Howard Woodwose. I heard there was a scientific party staying here.”

Summerlee frowned. “To be frank, I am not very well acquainted with Woodwose. He is a friend of my colleague Professor Creavesey, the palaeontologist. But yes, it is at his invitation that I am here, along with Creavesey, his students Gramascene and Topkins, and Mrs Creavesey.” He stared at me, a little warily. “You have heard tell, then, of our investigative enterprise?”

I shook my head. “Only that you are here. I must say, I found it difficult to imagine what you might find to investigate in such an out-of-the-way place. But if Professor Creavesey’s field is palaeontology, I suppose there must be fossils here.” I remembered passing a museum of such things in Ravensfoot, though I had not been tempted to visit.

Summerlee snorted. “A fossil would be more concrete evidence than Creavesey has managed to amass so far. No, our errand is an absolute wild-goose chase, but a scientist must be as committed to falsifying theories as to proving them. Even so, it was frivolous of me to come during term time; that, I fear, has been a disservice to my students.” His beard bobbed self-censoriously as he spoke.

“How intriguing.” I was conscious that I was echoing the prurient interest of Mrs Trice, but was unable to restrain my curiosity. “Can you tell me no more?”

He sighed. “The secret of our purpose here is not mine to divulge. Perhaps Creavesey or Woodwose will take you into their confidence, although I doubt it. There will be an opportunity at dinner tonight, I believe.”

There being some time still until then, I elected to walk a little way beyond the Mereside Hotel to the east. The professor declined to join me, pleading a paper he was to review, and I set off alone.

There was little enough left of the town in this direction. Beyond it, a rough track led across more meadows towards the spur of hill that reached down almost to the stagnant water. Though I knew that the recommended route up the fell, which I should take on the morrow, lay to the west, I was curious to see whether or not there might be another approach to the summit from this direction.

The fell’s shadow lay across all the land here, and the grass was sparser than it had been even on the other side of the town. As I approached, I saw that there was certainly no route up Netherfell this way. Along the ridge of the spur ran a drystone wall, constructed from large rocks settling together under their own weight without mortar, but that would be an easy enough barrier to pass. The problem would lie in reaching it, since the slope ahead was scree, a mass of dust and rubble that covered bare rock, and would make ascent all but impossible for any but the most experienced mountaineer.

At the end of the ridge, where it sloped sharply down to meet the lake, the drystone wall met a more formal construction, and the track ahead was bisected by a high wall of cemented limestone that extended some distance beyond the shore into the lake itself. This wall was broken by a large gate, which from my vantage looked large enough for a cart or carriage.

This, then, must be the way to Wermeston Hall, which I had been told barred the walker’s route on the eastern side of the lake. As I had been warned, it held no welcome for visitors, and I was not surprised that the locals saw fit to avoid it. I, too, turned back without going any closer, seeing no good reason to probe the shadows under the fell, and returned to the Mereside Hotel to dress for dinner.

At dinner, Professor Summerlee introduced me to his colleagues, and also to Sir Howard Woodwose, who came from his cottage on the other side of the town to dine with us. I was the hotel’s only guest not of their party, and they seemed disinclined to be forthcoming on the nature of their undertakings. I did, however, gather that they intended an expedition onto Wermewater the next day, where they intended to circumnavigate Glissenholm, the wooded island out in the mere.

To me this sounded more like a pleasure jaunt than a scientific endeavour, but I supposed that Creavesey and the rest must have their reasons, however frivolous Summerlee considered them. I had seen on my arrival that the hotel had its own mooring and a rowing-boat for the use of guests, but for my own part I had no intention of making use of the facility. In my mind boats have always been a necessary form of transport rather than a leisure pursuit. I was finding the dank shadows of Wermeholt oppressive, and frankly I was looking forward to quitting it for what I hoped would be the superior comforts of Hartsdale. Besides, I gathered that my dining companions intended to rise at six, and that in my view is no way to conduct oneself on holiday.

“I say, though,” Henry Gramascene suggested, “if you’d waited a bit until old lady Wermeston pops off, whoever inherits the estate might have given us permission to land on Glissenholm, rather than just rowing around it. I must say I’m curious about what’s there.” The student was loud and hearty, and seemed tolerantly amused by both his elders and his friend, the quieter Topkins. Despite his irreverence, I liked him instinctively.

“That is hardly respectful to Lady Ophelia, Henry,” suggested Edith Creavesey. “Her manservant explained to Sir Howard that her family burial plot is on the island. I can quite see why she would not want outsiders treating it as a curiosity.” Mrs Creavesey was a handsome woman, less than half the age of her balding, gnomelike husband. I gathered that she, too, had been a student of his before their marriage, and she had clearly profited intellectually from the experience. She was articulate and curious, asking intelligent questions that drew out fascinating strands of knowledge from her companions.

“Besides, her ladyship, though advanced in years, is hale and spry. Who can say how long she has left – or any of us for that matter?” Sir Howard Woodwose said. “Such things are not given to us to know.”

His voice was mournful, but his eye held an amused gleam. Though of advanced years, the great man had a relentless energy that I could tell after our few minutes’ acquaintance would make him the largest presence in any room. He was a huge man physically too, not overly broad nor muscular but quite six and a half feet in height, with a spade-like beard, and no sign of the self-effacing stoop that sometimes afflicts tall men.

“Well, she isn’t immortal,” Gramascene pointed out reasonably. “Or, if she is, that really is a scientific curiosity worth investigating. Have you known the family long, Sir Howard?” he asked, with an interest that sounded more than perfunctory.

“Only since my arrival in Wermeholt,” said the knight, “some ten years ago. At that time Lady Ophelia was not quite the recluse she has since become. She still walked the hills beyond her estate, and we encountered one another on the far side of Netherfell. I was able to tell her more than she had known of some of her family’s legends, and it seems she found the conversation sufficiently stimulating to seek out more of it. Sadly, her ladyship is unmarried with no living relatives, and it is a moot point to whom Wermeston Hall and its lands shall pass.”

“Why did she never marry?” I wondered.

“Really, Watson, do you imagine that the human animal can find fulfilment only with a mate?” snapped Summerlee, whom I knew to be a lifelong bachelor.

“On the contrary,” I said, “I have known several women who have been quite as devoid of interest in our own sex as some men are in theirs.” I was thinking of Holmes, of course, among others. “But I suppose that whatever her own feelings on the matter, the pressure on an heiress to continue the line must be very great.” Summerlee merely grunted in reply.

In some ways the Professor reminded me of Sherlock Holmes. His commitment to the facts, and his merciless application of logic, certainly explained his interest in my published reminiscences of my friend’s activities. But he shared none of Holmes’s passion nor his zest for adventure, and certainly none of his considerable personal charm. While Holmes could be sardonic and impatient, Summerlee responded to lesser intellects – which in his view included almost everyone – with the disdain that Holmes reserved for criminals alone.

I had heard both men characterised as thinking machines merely, lacking in emotion and empathy, as indifferent to others’ suffering as to their own, but nobody who read my stories closely, let alone met Holmes himself in all his glorious humanity, could sustain such a view of him. And in fairness, though many among my fellow medical students had described Summerlee as such, I could not believe that it was wholly true in his case either.

As I was the only one at dinner not privy to their secret purpose, the conversation of necessity turned to more general matters, and I asked Woodwose what had led him into such an unusual career as the study of myth and folklore.

“In my youth,” he confided in his deep, compelling voice, “I aspired to the priesthood, if you can believe such a thing. I was a pious young man, or so I imagined, and I talked my way into a theological college with a view to ordination.” His beard bristled white and his eyes shone with humour, though I could well imagine them burning instead with religious zeal.

I sensed as well that expounding upon his personal history was something of a habit with Woodwose, as he continued with practised ease: “Alas, as I read more widely in the religions of the world and their attendant mythologies, I came to realise that what excited me was not faith itself, but the legends and stories that surround it. I came to many of the same conclusions that Mr Frazer has popularised recently in his Golden Bough, though I did not, alas, think to publish them for myself.”

I searched my memory for what I might have read about this Frazer, but unearthed nothing beyond a vague sense that he sought to relegate Christianity to the moribund status of the pagan religions. The folklorist continued, “I left the college under something of a cloud, after questioning the morality of the ancient Christian evangelists who turned our ancestors away from the worship of their national gods, Woden and Thor and their peers. Who were those missionary saints, I asked, to decide that the destiny of our people lay with a deity from the Middle East, so foreign to these shores? Needless to say, this was not the kind of question that my prospective superiors appreciated from a priest-in-training.

“And so I parted company with both the seminary and the church, and turned my attention to the work that has consumed me since.”

“And the world of scholarship has been the beneficiary, Sir Howard,” Professor Creavesey assured him. “As have I, through the intersection of our fields of study.” The palaeontologist displayed a childlike enthusiasm for almost any subject of conversation, but the awe with which he deferred to Woodwose seemed excessive to me.

“I’m surprised that they intersect at all,” I said, prompting a look of concern as Creavesey realised that he might have said more than he intended.

“Oh, but they do, Doctor,” Woodwose assured me at once. “Fossils may inspire folklore, and folklore may influence our interpretation of fossils. You are familiar, perhaps, with the legend of St Hilda?” I admitted that I was not. “The story tells us that when the area around Whitby suffered a plague of snakes, the abbess prayed for a miracle, whereupon the reptiles all curled up and turned to stone, becoming the fossils known as ammonites. The coiled snake has become an essential part of her iconography, and appears on the town’s coat of arms. I understand a species has also been named after her, Professor?”

“Oh yes, I believe so,” Creavesey agreed, blinking.

“Hildoceras bifrons,” said James Topkins, the quieter student, eager enough now to share his knowledge of their shared subject. “The creature was never a snake, of course. It’s a mollusc with a coiled shell, similar to the nautilus. They’re one of the commoner types of fossil, and I believe especially prevalent around the Yorkshire coast. I suppose that’s why the locals felt the need to explain them.”

“Hilda of Whitby was a real historical figure, though,” Edith Creavesey observed. “The new women’s college at Oxford is named after her.”

“Of course, my dear,” the professor agreed at once. “A most intelligent and able woman, like yourself,” he added, with a fond smile.

“She played no small part in the Christianisation of these isles,” said Woodwose, a little censoriously, “but as with many so-called saints, some fascinating tales have accreted around her.”

“Isn’t there a similar legend of St Patrick?” I asked. “Didn’t he drive the snakes out of Ireland?”

“Ah yes,” beamed Woodwose, “but that story exists to explain an absence, not a prevalence, since the curious fact is that Ireland has no native snakes.”

“Shrewd of old Patrick to take the credit for that,” Gramascene observed. “I blush to mention it, but I myself banished all the tigers from Shropshire some years ago.” While it was clear that Topkins would one day follow in the footsteps of the older men, it seemed to me that Gramascene was concealing a certain impatience with their whole purpose, whatever it might be. I wondered whether he had come along solely to keep his friend company.

“Must you, Henry?” Topkins complained affectionately.

Woodwose gave a good-humoured laugh. “No, Topkins, Gramascene is quite right to prick my pomposity. I am afraid you have hit upon a subject upon which I threaten to become a bore, Dr Watson. The lore of serpents and their relatives is a particular area of interest of mine.”

I am afraid that at that point I rather closed my ears to his conversation, but it was in any case not long before we finished dinner. Shortly afterwards Woodwose bade us all farewell and left for the short walk back to his cottage, while Summerlee and the Creaveseys announced their intention to retire. Topkins and Gramascene were all set to stay up with brandy and cigars, and invited me to join them, but by now I, too, had had enough of company. I made my excuses and retired to my room, where I read for a while then tried to sleep.

Despite my weary limbs, I was unable to. Against my habit, I had taken a small cup of coffee after dinner, and I should have remembered how this always affects me. Sufficient time with the brandy decanter might have remedied the problem, but I was certainly too tired now to get dressed again and join the conversation between Gramascene and Topkins downstairs.

I lay awake for some time, then finally I got up, opened the window of my bedroom to the damp night air, and sat there smoking for a while. Having no need to see clearly, I did not light a lamp. The sky above was cloudless, though much occluded by the ominous bulk of Netherfell, and such stars as I could see were bright and clear. Although I could discern even less of the lake, it too was calm, and reflected the celestial lights perfectly. There was an otherworldly beauty to be found even in Wermeholt, it seemed, even if it was a paradoxical beauty bestowed by lights astronomical distances away.

Thinking of beauty reminded me of Mrs Creavesey, a striking woman with a penetrating mind. Her grace and intelligence seemed wasted on the elderly, weak-willed Professor Creavesey, and I felt it a shame that her husband seemed more under Sir Howard Woodwose’s influence than her own.

Why was she here, I wondered, or for that matter Summerlee or the students? I could imagine that Creavesey was sufficiently in thrall to Woodwose to welcome some eccentric collaboration that impinged upon both their disciplines, and perhaps it did make sense for him to bring his wife with him on such a visit, but his undergraduate students, not to mention an eminent anatomist, surely had more important calls upon their time.

It was a mystery, and for a moment I indulged myself by wondering whether it was one that would interest Holmes. My friend was wont to occasional protestations that it was the grotesque and surprising that interested him in the mysteries we investigated together, not the criminal element in itself, and there was perhaps some of that here. Yet I could hardly suppose that he would find this academic secret sufficiently alluring to draw him away from the bloodstains and fingerprints of the capital.

My musings were interrupted by the sound of a door being quietly opened, and then just as carefully closed. Had my window been shut I might never have heard it at all, but in my position by the casement I recognised the sound of the hotel’s front door. A moment later, I watched a dark figure appear in the street outside, stepping away in the direction of the church. From his broad back and youthful stride, I saw at once that it was Henry Gramascene.

I recalled being told that Sir Howard Woodwose’s cottage was beyond the church. Indeed, I must have passed it on my way into the town that morning, though I had of course been unaware of it at the time. Perhaps, I thought, Woodwose had left something behind here when he departed, though it would have to be some item of great importance to need to be returned to him that night. I could think of no other reason why Professor Creavesey’s student would be abroad at such an hour.

I was startled, then, when a moment later I heard the sound of the front door again, even more quietly this time, and a second figure appeared, silently following the first. This one was slender, and crept nervously, keeping to the shadows, but I thought that it could only be that of Topkins.

This was still more curious, but nevertheless hardly my business. If Gramascene had some nocturnal errand in Wermeholt, and Topkins some interest in following him, that was no concern of mine. I was on holiday, after all, and both men had seemed quite harmless at dinner. I had no reason to imagine any ill intent on the part of either, and there was no Holmes here to persuade me that their choice of tobacco or the state of their shirt-cuffs was proof of some nefarious intent.