22,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ullstein eBooks

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

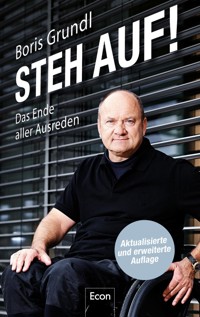

In seinem Buch zeigt Boris Grundl, wie er sein Schicksal am absoluten Tiefpunkt in die eigene Hand genommen hat, um sein Leben selbst-bestimmt und frei zu führen. Für den überzeugten Optimisten liegt heute das größte Glück darin, andere Menschen zur Entwicklung ihrer Potentiale zu inspirieren. Ein bewegendes Buch über mentale Stärke und Persönlichkeitsentwicklung und die Geschichte eines unglaublichen Lebens. Er ist Mitte zwanzig und hoffnungsvoller Spitzensportler, als es passiert: ein Unfall – und Boris Grundl ist querschnittgelähmt. Doch er gibt nicht auf. Als erster Rollstuhlfahrer schließt er sein Studium der Sportwissenschaften ab. Er wird Verkäufer von Rollstühlen, steigt zum Marketing- und Vertriebsdirektor in einem Großkonzern auf. Nebenbei wird er einer der besten Rollstuhl-Rugby-Spieler der Welt. Heute ist er ein erfolgreicher Business-Coach und beeindruckt durch seine Authentizität.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

The Book

In his book, Boris Grundl shows how he took his fate into his own hands at the absolute lowest point in order to lead his life in a self-determined and free way. For the convinced optimist, the greatest happiness today lies in inspiring other people to develop their potential. A moving book about mental strength and personality development and the story of an incredible life.

It happened in the Mexican jungle. A young top athlete, on holiday, jumps off a steep cliff, breaks his neck and can just about be saved from drowning. He loses every foothold he had in life, is paralysed from the neck down, dependent on a wheelchair and living on benefits. Life as he knew it seems to be over. But he doesn’t give up. Today he is one of the most successful business coaches in German speaking countries. Boris Grundl is an entrepreneur, a happy family man, does research on the topic of responsibility, has no financial worries and writes books. How was that possible?

The Autor

Boris Grundl is an expert in business leadership, an entrepreneur, coach, and popular keynote speaker. Through his “Institute for Leadership” he advises companies such as Daimler, SAP, and Deutsche Bank. He lectures as a guest at several universities, does research in responsibility and volunteers in schools.

Boris Grundl

STAND UP!

Good-bye to all excuses

Econ

Visit us online at:

www.ullstein.de

We select our books with great care, proofread them rigorously with authors and translators, and manufacture them to the highest quality standards.

Copyright notice

All of the content contained in this e-book is protected by copyright. The buyer only acquires a license for personal use on his or her own end devices.

Copyright infringement harms authors and their works. The further distribution, reproduction, or public dissemination is expressly prohibited and may result in civil and/or criminal prosecution.

This e-book contains links to third party websites. Please understand that Ullstein Buchverlage GmbH is not responsible for the content of third parties, does not endorse their content, and accepts no liability for such content.

ISBN 978-3-8437-2986-4

© Ullstein Buchverlage GmbH, Berlin 2022

Translated from German by Marc Wilch

Graphic inside text: Timo Wuerz, Andreas Gerhardt

Editing: Michael Schickerling, schickerling.cc, Munich

Jacket Design: FHCM Designagentur, Berlin

Jacket Image: Nico Pudimat

Drawings by Timo Wuerz and Andreas Gerhardt

E-Book: LVD GmbH, Berlin

All rights reserved.

Our fate is determined not

by what we experience but rather

by how we perceive what we experience.

Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach

My life shattered on impact

So, that’s what it’s like when you die.

I’m in the water and there is only one thought: “That’s what it’s like when you die.” I try to swim. But I can’t. Something is wrong with me. What’s wrong? I try to keep above the surface. But I slowly sink. I command my legs the way I have done thousands of times before: Swim! But they don’t perform the usual movements that would take me back to the surface, that would let me just tread water and float. It’s just not working. I continue to sink. I try again. Nothing. Something is different. What that may be, I don’t know. I don’t understand. My brain is totally baffled. I continue to sink. My head is half-way under water. I make frantic movements, swallow water in gulps. It’s like being in a bad disaster movie. Instinctively, my arms start moving more quickly. Ah, so there still is some strength. But it’s so damned exhausting. There is no uplift because of the lack of tension in my body. I am hanging in the water like a sack of potatoes, oblivious to everything around me. I don’t call out for help, that’s how preoccupied I am with keeping afloat. Fear sets in. Pure fear for my life. The more I paddle, the more frantically my arms move, the faster I seem to be sinking. The moments when my head is above water become fewer and fewer. I will sink to the bottom of the lagoon …

At the same time, I notice how my mind is expanding. I feel tranquility, clarity, a sense of complete relaxation. My mind continues to expand — in waves, in concentric circles, horizontally. And also, vertically. My mind rises, higher and higher, until I can see myself from the treetops, sculling in the water with my arms. From above, I see the jungle. The lagoon. The people by the water. I keep on fighting for my life. But my fear is no longer as intense. Instead, a sense of peace spreads through me. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if things could stay like this forever …?

From this same perspective I notice my friend Stefan running into the water. He is swimming toward me. Stefan is a good swimmer, I think. He will rescue me. At the same time, I return to my body. The peace and clarity have gone. I am terrified. I slowly realize that help is on the way. I don’t have to hang on for much longer, and I calm down to some extent. It takes a long time for Stefan to get me out of the water. My body is too heavy, and I am unable to help him. He holds me against a rock on the shore. With other people’s help, he finally manages to heave me out of the water. I lie in the sand, looking up at the treetops. I am breathing. I am alive.

My life suddenly decelerated from one moment to the next: from full speed ahead, unbridled restlessness, to slow motion. Up to that point I had been used to winning — now I had lost everything at once: my health, my prospects, my motivation for living. Everything had gone.

What was I left with? What meaning did my life have? I was full of fears and self-reproach. The same questions kept tormenting me relentlessly. Why had this happened to me? How could I have done something like this to myself? Why had I felt genuinely alive only on the brink of death? What purpose did my life have now? What would become of me? I didn’t have any idea of the consequences the accident would have for me. At first, I stubbornly refused even to give it any serious thought. Major feelings of guilt and self-pity ate away at my soul.

I was paralyzed, in body and mind. In those first weeks, I just let everything wash over me as if I had nothing to do with it. With a certain curiosity, I observed various nurses feeding me, when they attended to my incontinence, sucked the phlegm out of my bronchial tubes and did anything else that needed to be done to keep me alive. I had nothing to do with any of it. My body was alien to me. When the nurses were seeing to my needs, I felt like a sack of potatoes.

Me, the super athlete! I felt utterly defenseless. The bed I was lying in was what they called a rotating bed. It was meant to keep me from developing bedsores. Every couple of hours it flipped my body like a hamburger on a grill — from my back to my stomach and then onto my back again. I stared at the ceiling, turned, and stared at the floor.

Ceiling. Floor. Ceiling. Floor. An endless loop between ceiling and floor.

My field of vision was that of a baby in a crib: Anyone who did not bend over me closely enough was invisible to me. Even my consciousness became increasingly limited.

Ceiling, floor, ceiling, floor, ceiling, floor.

My little world was confined to my cramped hospital room. Beyond it, nothing else existed for me anymore. This rotating bed would become a metaphor for my life: Everything had rotated in a radical way.

I knew I was no longer the person I had been, although I frantically tried to cling onto my image. This strong, handsome, and successful young man had gone. I could not yet accept the fact. It wasn’t me, Boris Grundl, the tennis star, the golden boy who was always in high spirits, the charmer and ladies’ man. Now I was a cripple.

Well, and how about today? Today I am one of the most sought-after leadership experts and keynote speakers in Europe. I write books and have founded the Grundl Leadership Institute, an organization among the top destinations for transformational management training. My financial means allow me to live in Spain and Germany. I am married to a fantastic woman and have two wonderful adult children who are forging their own paths in a remarkable way.

Learning to understand life

Perhaps you are now asking yourself: How can someone experience such a defeat, such a deep fall into a bottomless abyss and turn it into victory? How did he achieve this? How was it even possible?

I had to learn to understand, to understand deeply what had happened. Initially, I needed to understand myself and my new situation. And then I had to learn to understand others. To understand relationships, my family. Later, professionally, I needed to understand markets, companies, production, sales. Understand meaning, human growth and development, transformation. To understand life. And that is precisely the point: First, it was about learning to understand life and its principles. Not my life. That is the crux of the matter: Most people first want to understand their own life so they can then understand life in general. That is a cardinal error! It’s necessary to first understand life and then to understand your own life. That’s the right approach, and it lets you achieve a healthy distance from yourself.

My life: This life map emerges almost solely from my own experience.

Life: This life map emerges from my own experience and the experiences of others.

Today I know that individuals who intelligently reconcile their own experiences with those of others will recognize the powerful laws of life more quickly. They will make wiser and more far-reaching decisions, which will lead to substantially better results.

I was first preoccupied with myself and my life, so I had to learn to ask myself better questions. Instead of: Why did this happen to me (my life)? It would be: What lesson does life want to teach me through this experience (life)? Instead of: How could I do this to myself (my life)? I needed to ask: What good came from the whole experience (life)? I admit, it was anything but easy — it took a lot of discipline.

The ideas behind this different kind of thinking must meet three criteria. Firstly, they must inspire me to move from self-reflection to action, because inspiration is the result of wise self-reflection. Secondly, they must deliver the desired results after action is taken. And thirdly, they must also be able to deliver the desired results for aspiring students at our institute. Only then do I dare to write and speak about them.

I don’t mean to imply in any way that I’m always in control of all these principles myself. All too often, I fail in applying them. I’m aware that I fail daily to abide by these laws of life — as a husband, a father, a colleague, an entrepreneur or simply as a human being. Getting yourself to fail less and less is not easy. Practicing transformation, not just preaching it, means exactly that: to fail less and less. Because every winner stands on a mountain of defeats. That is clear to me today, crystal clear.

I now manage more and more often to live my life like this. After all, the point is not to achieve perfection. Nor is it to live a perfect life. The point is to live an inherently consistent life. A life you are called up to live. To my mind, it’s not a matter of what “I want” or “don’t want”. It’s a matter of “what is my purpose on this earth?” That sounds completely different: It’s a life full of meaning, a calling, a vocation. This meaning in one’s life stems from a highly individual journey of self-discovery. And this inward journey makes every life unique and exciting. I am convinced of that.

I wouldn’t like to be the man my parents see in me. Neither would I like to be the man my spouse wants me to be. Nor my boss. Nor society, for that matter. And I am also not the man I once was. I am the man I am now!

For me, the power of living a free and self-determined life is encapsulated in these statements. I’m convinced that these ideas become more and more crucial for every human being, every day. From the day we start reflecting on “our existence” to the day of our death. In the future, it’s not a question of us going higher, faster, further but rather of being more flexible, clearer, deeper. To do so, we must learn to understand, without letting ourselves be pressured into agreeing to everything. It’s an art to understand something without necessarily having to agree with it.

Fate has taught me some intense lessons and treated me to many wonderful ones. Lessons I had to learn to recognize and to acknowledge. I’m not saying that my insights are “true and correct”. Not at all! I cannot and do not want to make that claim. Yet through constant reflection and action, I’ve gained a world view I can also offer in my work with people learning to reflect on their lives. The same is true of this book. I’m opening myself up as much as possible and as effectively as I can, so everyone can benefit from my limitations, learning processes, and insights. That’s the point, even if I make myself vulnerable and lower my defenses in the process. The effort is worthwhile for everyone who makes headway in their life after reading this book.

I had to learn to understand all this in my rotating bed. At first, I couldn’t come to terms with my situation at all. And I thought I never would. Yet today I’ve come to grips with it. If the accident hadn’t happened, I would not be the person I am today. That’s why I like to irritate people at my lectures by saying: I would dive again.

After my friend Stefan pulled me out of the water, I knew: I am a paraplegic — even if I couldn’t fully grasp it at the time. What good can possibly come of this, I asked myself back then. And: What parts of me still function? What is possible now? Does my life still have any meaning? Strangely enough, I had an answer to that last question pretty quickly: You could live your life in a way that would be an example for others. An example of the stuff all human beings have inside them, better and more truthful than before. This solid idea, this image gave me the strength to persevere over all these years. I thought time and again I should write something about this experience; even at the hospital in Mexico I decided to document and record everything. But it wasn’t possible. I was not in a position to do so until 2008. Only then I understood my story well enough myself. It would take 18 years before I was able to tell it. And another 10 years to arrive at the depth and substance I have today.

I’m eternally grateful that my story gives so many others inspiration and confidence. Also, that I have the privilege of sharing my experience, my knowledge, my insights worldwide in so many lectures, seminars, coaching sessions, and books — including now, for the first time, also in English.

I know from countless letters and emails that many people have been inspired by my life story. I hope you gain similar inspiration from reading this book. Please feel free to send me an email with your feedback: [email protected]. I look forward to your comments.

Boris Grundl

1Focus on what is there — and make the most of it

“Do what you can, with what you’ve got, wherever you are.”

Theodore Roosevelt

It was like a scene from “Taste of Paradise”, that Bounty chocolate bar commercial from the late 1980s: I was lying in fine, white sand, above me the azure blue Mexican sky. The sun was shining. I could hear the nearby waterfall cascading into the lagoon, a turquoise, mirrorlike surface surrounded by lush green jungle. But something was wrong with this commercial. The moment I tried to move my legs I knew: I was paralyzed. Paraplegic. Back then I had no way of judging the level of my paralysis, all the details I know today were unknown to me at the time. Nonetheless, I grasped my situation immediately: This is what it must feel like, I thought, as I reached out to touch my legs. Yes, this is what it must feel like, the medical state I had learned about during my sports studies in a physiology course: paraplegia caused by a spinal lesion. To calm myself down, I checked the rest of my body: What could I still feel? What could I still move? Other questions shot through my brain: What was left now? What sense did my life still have? Although I realized I could only move my hands, my mind was completely clear. I was calm, functioning like a robot, as if it all had nothing to do with me. Today I know: What I was experiencing was shock, adrenalin. I felt no pain, not at that point in time in any case. I just couldn’t move.

“Boris, can you hear me?” The face of my buddy and travel companion Stefan loomed over me. I had planned the whole trip with him; the two of us, both students, had decided to take off together one more time before life got serious. He had pulled me out of the water and saved my life. Yes, I was able to hear him. I just couldn’t move. Then other voices hit my ears: “What’s wrong with him?” The tour group gathered around me. We had left the hotel together to visit this delightful bit of paradise. I heard their voices, loud and clear, but as if from a distance. I saw horrified faces, wide-eyed and open-mouthed, bending over me but I did not perceive the actual people behind them. Their feelings hit me with even more impact. I sensed their emotional states — from fear and helplessness to despair and panic — so intensely that I felt the need to help them. Crazy, considering the situation I was in! This continued to happen to me frequently from then on. But I didn’t allow myself to help them. Just as I forbade myself to let the group’s feelings get to me. I did not allow myself to be frightened. You have to function in order to get out of this jungle, I thought.

I knew that something horrible had happened. I was even certain that I was paraplegic. But I did not allow myself to panic, to lose my head, to be literally outside myself, instead of remaining inside my body. And that also answered my question about what still worked: My mind was clearer than ever, my will to survive was strong. I concentrated on what was left to me, in this case, my clear mind and my willpower — of course, only intuitively. Today I think this attitude saved my life. Stefan had saved me by rescuing my body out of the water. Then my mind saved me yet again by fending off the fear of the others. And even more importantly, by resisting the clumsy attempts of my rescuers to carry me away.

“Don’t touch me!” Those were my first words. I repeated them again and again until the group did what I said. “Hands off! Don’t touch me!” I knew what could happen if they tried to lift me. A single wrong move might be enough to cause further damage to my spinal cord by shifting the vertebrae. “Find a door!” I yelled out. “Get a door you can lay me on.” I have no idea where this idea came from. The only thing I knew was that I somehow had to get them to immobilize me. Any additional movement would have meant even more extensive paralysis — or even my death.

Not far from the lagoon, the jungle opened onto the sea. In a house on the beach, several members of the group found a door and took it off its hinges. I remember vividly to this day that it was blue. They carried me on this blue door up the beach to take me to the hospital by boat. There were no paved roads in the jungle; water was the main thoroughfare. The distance we traveled by boat seemed like miles and miles to me — in reality, it was not more than 200 yards, lying on my door. Next to me was the group’s travel guide, shocked and sobbing. I did not let any of this affect me. In fact, I even suppressed the certainty of being a paraplegic. Instead, I only thought about the next step. I wanted to get out of the jungle and make it to the hospital. At least you can feel no pain, I thought. That was true. I was still in a state of shock.

About an hour after the accident, I finally arrived to the hospital, where sheer chaos reigned. I was lying somewhere in a hallway, still in my swimming trunks, my body covered with sand. Stefan was phoning my parents, who nearly lost their minds with worry. Some financial details had to be worked out. I was supposed to be operated on quickly to prevent my condition from deteriorating. But who would foot the costs of my surgery? And who would pay for my return home? My parents were already planning to take out a loan. Just minutes ago I had been the hero in that Bounty commercial. Now I felt like I was in a bad insurance ad. Fortunately, someone found an insurance policy in my name.

Of course, these things had to be settled. I understood that but it didn’t interest me one bit because I was caught in my own nightmare. The shock subsided and the pain came rushing through me like a tsunami. I experienced not a single breath, not a single movement without the feeling that someone was ramming a blade into my neck and then turning and twisting it. Welcome to hell on earth.

The shocking truth

At the same time, I was slowly becoming aware of my situation. Along with the pain came the fear, but in waves, an ebb and flow. Not every hour but within minutes. A constant coming and going. The physician treating me had used a stretching device attached to my head with clamps to fix my broken spinal cord in place between the sixth and seventh vertebrae of the neck. Ever since then, not a single hair has grown on the spots where the clamps were lodged — at the back of my head and under my chin. I looked like the main character in A Clockwork Orange and felt like him, too. My field of vision was totally limited; all I could see were the cracks in the ceiling of the room. I felt and saw nothing of what was happening to my body, whether it was being fitted with a urinary catheter or receiving an infusion.

The pain changed. Now it felt as if the bones of my sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae were poking through my skin. The crushed nerves did in fact hurt — or, to be more accurate, the part of them that had not yet been destroyed. I was still able to localize this pain precisely. The diffuse pain and side effects with which my body and mind sought to fight this new situation — phantom limb pain, fever attacks, phlegm in my lungs — would not start until I was back in Germany.

When I did manage to ignore the pain, fear arrived in its place. And the same questions kept tormenting me, relentlessly: What was my life worth now? What would become of me? I didn’t know exactly what consequences the accident would have for me and still refused to think about it. This much was clear: Prior to the accident, I had been a top athlete. Now I knew I could forget about my career as a tennis player and coach. But there was still my second major passion besides sports — music. Then I’ll just study saxophone and clarinet, I told myself, I can still move my fingers. But that too would soon change. “Still” — I did not know at the time what power this inconspicuous word could have.

In Mexico I underwent the first surgery. I was not afraid. I had been told that my surgeon was a neurologist and had studied in the United States. After the surgery, mobility in my fingers decreased, but I was still not worried. Don’t panic, I thought, this may be part of the process, mobility is sure to return. It did not. Instead, thanks to the insurance company a Learjet arrived from Germany to fly me home. The German doctor accompanying me was shocked by the chaos in the hospital and by my condition. His words still ring in my ears. He entered the room and greeted me with the following words: “For God’s sake, we have to get you out of here!” So, two or three days after my accident, I ended up leaving the country I had fled to in order to escape the serious side of life — and found that it had caught up with me in full force.

A flight in a small, twin-engine Learjet from Mexico to Germany is not as quick and uncomplicated as with a holiday airliner. For safety reasons and for refueling, we made numerous stops in Canada and Greenland. On finally landing in Germany after what had seemed an eternity, I was taken to a special hospital in Markgröningen near Stuttgart. Home at last. Was it a good thing? There was nothing good about it! My inner calm and self-control disappeared, along with my concentration. On the way from the airport to the hospital I asked every three seconds: “How much further?” Suddenly the new reality had caught up with me in my old world. I became delirious. Self-control didn’t work anymore. I was completely shaken — physically and mentally. Welcome to the reality of paraplegia.

Self-pity gnaws away at self-esteem

When I arrived at the hospital in Germany, the Mexican sand still clung to my body and now smelled terribly. I underwent a kind of post mortem while still alive. At least it seemed like that to me because the people around me were talking about me as if I were not paralyzed but dead — or deaf. I mostly picked up on the body language and the tone of voice. It was not the words, but rather how they were said. The contents were intended to have a positive effect on me, but failed. The manner of speech communicated more than the words did. Time and again, they repeated, like the music you have to listen to when you are put on hold: “There he is, our cliff diver from Mexico.”

“Too bad, they say he was once a fantastic tennis player.”

“Yes, you can see that, too. Look at those muscular legs! So fit and so tanned …”

“It’s hard to imagine he has no feeling in them anymore.”

“Well, I couldn’t bear it. You can’t call that a life anymore. Also, as a man, I mean, nothing down there works anymore.”

“Yeah, and being fully dependent on others to do everything. Feed you, wash you, change your diaper you for the rest of your life … that really sucks!”

I wanted to scream at them: “I’m paralyzed, you idiots, not deaf!” But I was completely defenseless and incapable of doing anything. I wasn’t even able to wash the sand off my body. I needed their help for everything, and as time went on, they talked about me as if I wasn’t even there. The more my self-esteem shrunk, the less they saw me as a human being deserving of respect. Today I know this happens not only to paralyzed individuals.

This double defenselessness was getting me down. At the same time, they were saying exactly what I was feeling. I knew myself I would never be the man I had been before: that strong, attractive and successful young man had ceased to exist. And what was I now? A cripple. I couldn’t accept that. That just wasn’t me. Not me, Boris Grundl, the tennis star, the golden boy who was always in a good mood, the charmer and ladies’ man. I clung to my old self, didn’t want to give it up, didn’t want to be disabled. Disability — as a fully functioning person before, I had formed a picture of what that meant. Just like everyone else. I was then still a person who could walk upright on their own, and I kept thinking like that person even when I no longer had any feelings in my toes.

During the months of hospitalization that followed, my attitude initially didn’t change. On the contrary: The more aware I became of my situation, the more vehemently I rejected it. I rejected myself. I could only see the humiliating aspects of my situation and felt more useless than a house plant. Plants can at least show gratitude for being watered by blooming once in a while. I withered inside. On my rotating bed, my own personal rack that was meant to keep my body from developing bedsores, I was continually turned from one side to the other, like a suckling pig on a spit. Imagine the bed as the slices of bread in a sandwich — and I was the filling. I looked at the ceiling, was turned, looked at the floor. Ceiling, floor, ceiling, floor. My field of vision was that of a baby. Anyone who didn’t bend over me far enough was invisible to me and my consciousness also became increasingly limited. My little world was confined to my cramped hospital room. There was nothing for me beyond its walls. Above all, I was as dependent as an infant, just as the nurses had predicted. I was fed, washed — and turned over once again.

During the long nights when silence fell in the hospital hallways, loneliness came. I was terribly sad and desperate, afraid about the future: What would become of me? I was unable to take care of myself, I was a high dependency case who would have to live off his parents and the state. The way things looked I wouldn’t be able to live by myself. What about my sports degree? What about driving? Would I ever be able to have a job? I knew I would never play tennis again, never reach out and pick up my saxophone again. I had no alternative to these things, not even the inkling of an idea about what I could replace them with, just this overwhelming feeling of being absolutely useless. And who would ever take me, a picture of misery, seriously again? Since I no longer trusted myself to do anything, no one else would think I’d be able to do anything with my life either. And what about women? They don’t find cripples attractive. At best they might pity me. Later self-reproaches crept into these thoughts: How could I have done something like that to myself?

The magic of change

When I lost control over my life, I had just turned 25. I saw only my losses and thought that my future consisted only of my past minus all the things I was no longer able to do. That was my blind spot. I saw only what I had lost, not what was still there. A few years later, I would find out that the celebrity paraplegic, Superman actor Christopher Reeve, had had a similar fate. Reeve was paralyzed from a few centimeters higher up in the body than I had been and had hoped until his death in 2004 that he would one day walk again. He too was unable to let go of the past, wanted to return to whatever society considers normality. I remember seeing the TV images of a paralyzed Reeve trying to walk two steps under excruciating pain, cheered on by hundreds of people who could walk normally as he attempted to become one of them himself. The images really made me think. I wanted to call out to him: “Let it be! Why do you want to be able to walk again? Why are you concentrating on what you no longer have? You would be better off concentrating on what you can do!”

Concentrate on what you can influence.

But what I had wanted to tell him was something I first had to grasp myself, and I could only do that after my second surgery. Maybe I hadn’t expected a successful operation. At the time, I couldn’t even move my fingers anymore, and that was exactly what my surgeons wanted to change with the surgery. They tried to recover my triceps and parts of the muscle strength in my hands. With my right triceps, they were 60 percent successful. With my left, 40 percent. With my hands, they were 7 percent successful on the left and 15 percent on the right. When I was able to move my right thumb again during a post-operative muscle test, I was baffled when the doctors literally started cheering. My own joy was more reserved. Although it did me a world of good to see the surgeons respond the way they did, I remembered the old German saying: “Don’t praise the day before the evening” — the equivalent of the English, “Don’t count your chickens before they have hatched.”

As it slowly dawned on me what the progress of my thumb meant, I wept for joy. What a gift, I thought, and began to visualize all the things I would do with this thumb. I could turn book pages, press the buttons on a remote control, operate a computer mouse, hold a spoon. Maybe I would even be able to drive a car! That was my world now — a whole universe in this one thumb. I had completely given up on my fingers and no longer expected any improvement. That made me all the more joyful about my thumb and later also about the strength I subsequently recovered in my fingers.

Today I realize that this situation led to the most crucial insight of my life. If I hadn’t hoped so fervently back then to become “normal” again, I wouldn’t have been able to rejoice so much about the mobility of my thumb. Instead, my only thought would have been: Damn it, I want my old life back! Like Reeve, I had been fighting a battle with the world around me that I was doomed to lose. It was only when I was willing to take up the inner fight that my perspective changed. It was only a small break, a minimal shift in my perception, but suddenly everything was different: I felt good. I had a deep sense of gratitude. I was happy about what abilities I had left instead of being angry about what was no longer possible. Of course, I tried every day to reactivate the parts of my body that were paralyzed. And I continue to do so to this day. But I never again become lost in hope or expectations.

Concentrate on what you’ve got — and make the most of it! This realization has become the philosophy of my life. And by focusing on my thumb, I suddenly had much more than before. New paths opened when I recognized that my thumb was an opportunity. Today I’m still 90 percent paralyzed but I concentrate on the 10 percent of muscle function that I do have. It means more to me than the 100 percent I had prior to the accident. My thumb represents just the first of many doors that opened for me. I certainly had to struggle for a long time to realize this was a rocky road, and I’m still fighting this today. Sometimes it is still painful and lonely.

It wasn’t only the realization I struggled with, but also the willingness to let go. The joy I felt about my thumb was not only the first sign that I was confronting my situation head-on, but also that I had accepted it. And not intellectually — through the eyes of someone without a disability — but emotionally. It was only this deep acceptance of reality that enabled me to change my perspective. The crisis then gave rise to new opportunities. This incident illustrated the problem: Many people know what should be done (intellectually) but fall short of becoming emotionally convinced. A person doesn’t lose weight by simply knowing how to do it (intellectually), but rather by actually consuming less food or by burning up more calories (emotional insight). Most people don’t lack intellectual knowledge but rather the emotional strength needed to apply it. And: The question is not whether a crisis can become an opportunity but rather what makes a crisis turn into an opportunity.

This experience is the first I share in my work as a coach. I mention it in every single lecture. The ability to concentrate on present capabilities is the first building block of a simple yet incredibly powerful philosophy that can be applied in all spheres of life. Just ask yourself as a manager: What in your life, company or job represents that thumb? It may be hard to determine. Many people work for years with their index finger even though their thumb is the digit with real talent.

As a manager you should also shift your perspective a little for a change and examine the resources of your company and assess the talents of your employees. Do you feel happy about what you might find? Or are you taking people for granted? Do you only see apparent shortcomings rather than potential? Do you ask yourself: Why in the world am I working in a company with such low sales? And why is our marketing budget so small? That is like me saying: “Sorry, I am indisposed at the moment, I am sitting in a wheelchair.” At least you have a sales department and a marketing budget! If you concentrate on the things that already exist, they become better, and you are less likely to notice whatever is missing.

Incidentally, when I talk about concentration, I mean it absolutely literally. I will give you an example: One day, I drove my car to do some shopping and was on my way to where my vehicle was parked. It was raining cats and dogs. I was in my wheelchair next to the car and wanted to heave myself into the driver’s seat, normally one of my easiest routines. But that day there seemed to be a spanner in the works. Ten minutes later I was still sitting there. I watched others passing by, going to their cars and simply getting in without giving it any thought. I didn’t want to let myself go and start envying everyone else — because then I would have lost. I had to remain grounded. What good would it do to envy the people passing by? That wouldn’t get me out of the rain any quicker. On the contrary! I had to concentrate on what was possible. Suddenly I saw the right way to go about it and figured out what I had been doing wrong in my previous attempts to get into the car.

Something has been clear to me ever since: Envy is nothing more than a mind going haywire and becoming preoccupied with other people. The envy factor is at play everywhere in daily life and limits people tremendously. It is not helpful to focus on what others can do or what they have. Envy simply diverts our attention from our own capabilities.

Wealthy people run the risk of taking everything for granted — one of the greatest diseases of Western civilization. Fortunately, you have the freedom to decide for yourself. Do you allow yourself to be tormented by thoughts of the past, by things that you don’t have? Or do you focus on making something of who you are now? When you get older, will you be angry about your past life or happy about the possibilities offered to you in each phase of your life? The list is endless.