5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Some legends are written in blood. Spartacus is the hit TV show which combines blood-soaked action, exotic sexuality, villainy and heroism. This original novel from the world of Spartacus: Blood and Sand tells a brand-new story of blood, sex and politics set in the uncompromising visceral world of the arena. The gladiator Spartacus, the new champion of Capua, fights at the graveside of a rich man who was brutally murdered by his own slaves. Seeing an opportunity, ambitious lanista Quintus Batiatus plots to seize the dead man's estate. In the arena blood and death are primetime entertainment. But not all battles are fought upon the sands...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

COMING SOON FROM TITAN BOOKS

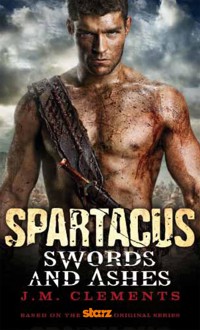

SPARTACUS

Morituri by Paul Kearney

J.M. CLEMENTS

SPARTACUS

SWORDS AND ASHES

BASED ON THE STARZ® ORIGINAL SERIES

TITAN BOOKS

SPARTACUS: SWORDS AND ASHES

Print edition ISBN: 9780857681775

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857687289

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UP

First edition January 2012

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

SPARTACUS TM & © Starz Entertainment, LLC. All rights reserved.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the United States.

DID YOU ENJOY THIS BOOK?

We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

FOR ANDY WHITFIELD

1972-2011

Contents

I THE IDES OF SEPTEMBER

II JUPITER PLUVIUS

III HOSPES

IV IMAGINES

V BUSTUARII

VI CENA LIBERA

VII ROMA AETERNA

VIII VENATIO

IX MERIDIANUM SPECTACULUM

X AD BESTIAS

XI PRIMUS

XII SPOLIARIUM

XIII ARGUMENTA

XIV FENESTRAE

XV SICARII NOCTE

XVI GLADII ET CINERES

XVII POSTERITAS

XVIII RECONCILIATUM

Acknowledgments

About the Author

I

THE IDES OF SEPTEMBER

HE PICKED UP A FRUIT KNIFE AND TAPPED GENTLY ON THE SIDE of a goblet. The sound barely traveled at all through the noise around him. Raucous laughter rolled over girlish giggling, the drums and pipes of the band, and the clash of finger cymbals from one of the few dancers still standing.

Pelorus climbed unsteadily to his feet, using the table for support, blocking the diners’ view of the two-horned crest of his house, which hung on the wall behind him. His fingers clutched at the wine-stained tablecloth, snagging and dragging several dishes toward him. A lamp clattered to the floor, bouncing into the shallow atrium pool, where it joined several floating dishes, apples, animal bones and a partially submerged, half-eaten bunch of grapes. The lamp sputtered and died, leaving a tail of fading smoke and an ever-growing film of oil on the surface of the pool.

“Friends...! Romans...! I entreat you! Silence for but a moment or two,” Pelorus called, half laughing. Someone in the shadows told him to fuck off, and there was more merriment all around.

Pelorus wrapped his fingers around the stem of the goblet, forming a crude hammer with which to bang on the table. He brought it down three times with the practiced aim of a man who knew how to smash things up. Red wine dregs shot across the table, adding to the stains.

“Still your tongues! Every one of you!” he shouted.

And then there was something close to silence.

“Gratitude,” he began, “for honoring the House of Pelorus with your presence here today, before each of us had consumed too much wine for sense to be made!”

Cheers issued forth from half a dozen diners, and there was polite applause from the women in the room whose hands were not otherwise busy.

“And though wine abounds—” cheers again— “be certain to sample the services of the House of the Winged Cock, flavors sweeter even than what fills cup.”

One diner in particular greeted the news with great enthusiasm, half rising to his feet from his couch, tripping and landing on his knees in the shallow pool. Water sloshed over the opposite abutment, while the others laughed and pelted him with grapes.

“Valgus!” Pelorus laughed. “Caius Quinctius Valgus! We shall have to free you from wet attire!” More cheers followed as Valgus’s lady companion tugged at his sodden toga, deftly disrobing him in the manner of one well used to such endeavors.

“Welcome, Valgus, old fool,” Pelorus said. “Welcome Marcus Porcius, and other dear friends from Pompeii. Welcome, too, guests who have journeyed from Baiae and Puteoli. Welcome good Timarchides, fixer infamous. Your presence here at the table is well deserved and long overdue! I trust you will find the house of Marcus Pelorus most hospitable!”

Pelorus paused, basking in the glow of approbation, watching in the light of the flickering lamps as his guests hollered their thanks. He glowed with their love and then held out his hands in a plea for silence once more.

“We are here for celebration of a day of great fortune for our society of Campanian investors. The noblest among us, Gaius Verres, departs Neapolis in but a few days, to take up a post well deserved as governor... Yes, governor! Of all Sicilia!”

Cheers erupted once more.

“To eternal good fortune, and an abundance of coin!”

Pelorus raised his goblet, which had been discreetly refilled, and dropped a stream of wine into the atrium pool. The diners watched in respectful silence as their host invoked the sacred spirits, and offered due homage to the unseen gods.

“I offer this libation in fervent hope of safe travel for our good friend Verres, as he departs Neapolis aboard ship. May his governorship bear fruit of prosperity for his house and for the good people of Sicilia... Those poor, poor bastards!”

The loudest cheers of all shook the walls, drifting into the Neapolitan night sky.

“Gentleman, I give you Gaius Verres, our worthy representative in Sicilia!”

The garden erupted with cries of “VERR-ES! VERR-ES! VERR-ES!” which soon petered out as heads peered around the gathering.

“Wherever the fuck he has gone!” Pelorus giggled, lifting the tablecloth experimentally, and finding nothing.

“I care not!” Caius Valgus yelled. “Matters of greater import plead diversion!” And he pointed down in glee at the woman on her knees before him in the atrium pool, her head bobbing enthusiastically between his legs.

Gaius Verres heard people chanting his name, and then the sound of the band striking up once more. The party would have to go on without him as he explored the darker recesses of the house of Pelorus.

Rooms not intended for the celebration were sparsely lit by solitary oil lamps, and many had already sputtered out. The household slaves had other duties, and the party had already far over-run the length of the average taper.

He could hear the woman sneaking up on him, if one could call it sneaking when there were bells on her ankles.

“Verres,” she stage-whispered down the hall. “Verres? Do you hide from me?”

He ignored her and lifted his lamp. The room was bare, but for a small shrine to household gods, and a wooden sword hanging from the wall. Verres shook his head and sighed.

“Where lies the adventure, Pelorus, you cock?” he muttered to himself. The ankle-bells tinkled closer with exaggerated steps, and Verres was suddenly enveloped in a sheer scarf of Syrian silk.

“Whose cock?” she asked.

“I was not addressing you,” Verres said impatiently.

“Maybe you are not one for conversation,” she said, her voice lilting with the hint of a Pompeiian accent.

“I do not desire your company, woman...”

“Successa. I am called Successa.”

“As you say.” Verres pushed the scarf aside and continued to the next room, fast enough to risk putting out his lamp with the breeze of his passage.

“Successa is my name,” she almost sang it, “Successa is my nature.”

“I am certain many find that true.”

“Why not come close and discover its truth for yourself, Governor Verres?”

“My tastes lie in other achievements.”

“But good Pelorus wills it so.”

“Leave me and fuck him, then.”

With surprising strength, Successa grabbed the governor-designate and pinned him to the wall. Verres dropped the lamp in surprise, dashing its contents into the floor mosaic in a sudden lattice of gentle flames. Successa pressed her hot mouth onto his, her tongue probing, her arms pulling his head closer. She pressed her breasts against him and locked one leg around his calf.

Verres twisted his head away.

“Sample my wares but once, Verres,” she insisted, “and your cock will never seek another resting place.”

“Leave me be, woman.”

Verres pushed her away. His eyes widened as he saw what he was looking for: a staircase down half a floor to the lower level of the house.

“Pelorus’s purse is heavy with coin. And I am tasked with lightening both purse and cock,” Successa insisted.

She watched in bafflement as Verres gingerly descended the stairs. The former flash of brighter light from the broken lamp was almost fading; the burning oil on the floor already reduced to low simmers of dying blue, the door to the lower level almost entirely hidden in shadow.

“That portal offers path to cells where slaves reside,” Successa said disdainfully. “You will discover nothing there of worth.”

Verres ignored her and lifted the latch, opening onto a corridor of roughly assembled brick. Torches, not lamps, flickered every ten paces. He snatched up a fresh brand, and lit it from a sputtering stub in a wall-bracket, waiting patiently as the flames licked around the tar-soaked rags until they hissed into fiery life.

Successa pulled the ankle-bells from her feet and followed.

“Gladiators and slaves,” she whispered. “Middens and storerooms. Is that what kind of man you are, Verres?”

Verres smiled to himself in the half-light.

“Do you seek the company of women at all?” Successa mused.

Verres snorted.

“Accept, Successa, that my interest simply does not lie with you. My meaning is not to offend.”

“Am I too old? Too forward?”

They walked past barred alcoves, each containing one or two dozing male bodies. Some weary heads lifted, only to fall again as Verres passed. Scattered wine flasks in each cell attested to a low-rent copy of the celebrations upstairs.

“I have learned many things,” Successa continued. “In Cyprus, the birthplace of the goddess of love. In Egypt, origin of many dark arts of the bedchamber.” She frowned at the complete lack of effect she seemed to be having. “In Rome itself, where no true man could resist these thighs...” she added petulantly.

“I simply seek something different,” he murmured.

“I can be different.”

Verres had stopped outside one of the cells.

“Now that,” he said appreciatively. “That is different.”

The cell was entirely bare, lacking wine or the remains of any supper. Inside was merely a rough covering of sackcloth, drawn over a prone, shapely form. She was already awake, dark eyes glinting in the torchlight.

“Is she a gladiator?” Successa asked.

“Do not be a fool,” Verres replied. “Pelorus does not deal solely in gladiators, nor does he tender all coin for spending. This, he locks away as treasure.”

The woman in the cage stared back at him impassively, without fear. Verres lifted the slate by the entrance, reading five letters scratched onto it.

“Medea?” he said. “An ill-fated name for such a little mouse.”

She clutched the sackcloth against her chest, not carefully enough to hide a shapely breast and pointed nipple. She drew her legs toward her, as if recoiling from the light.

“There is no place to run, little mouse,” Verres breathed.

The woman in the cell shook her head in denial, as if willing Verres to disappear, in vain. There was something on her face, like the tendrils of a plant, or matted hair. It was difficult to see in the half-light.

“Suddenly she is coy,” Successa observed with a sniff.

“As well she might be,” Verres smirked, handing Successa the torch.

“She is nothing,” Successa said disdainfully. “Why trouble yourself with earth when you can be grasped by the thighs of the heavens?”

Slowly, ceremoniously, Verres unhooked the lock that lay open in the metal loop, and lifted the bolt that kept the cell door closed. He slid it slowly along its loops with a scraping of dry, old metal.

“Temptation enough for most men,” he said to Successa, tugging at his belt. “But one is never closer to the heavens than when one does the taking.”

He let his tunic fall to the ground, looking faintly ludicrous in nothing but his sandals. His left hand snaked between his own legs, rubbing gently at his hardening member. His right hand tugged at the heavy cell door, which creaked open on protesting hinges.

“I am a woman valued many times higher than her,” Successa protested.

“I do not desire two women,” Verres chuckled. “Not this night at least.”

“Why do you seek to make your life difficult?” Successa said, scowling. “She will fight you.”

“That is my very hope,” Verres whispered, moving slowly, deliberately toward the trembling figure.

The woman named as Medea backed further into her corner, her eyes wide with fear, her back meeting unyielding brick.

“You cannot escape from me, little mouse,” Verres said. He leaned forward and grabbed her hair in his fist. “So show me what you have to offer.”

He dragged her to her feet, the sackcloth falling away to display her naked body. Successa gasped in surprise as she caught sight of a network of regular scarring, at tattoos and swirls, incisions rubbed with colored dirt. The entire left-hand side of the prisoner’s body was a work of savage, Scythian artifice, slashed with a thousand knives in careful patterns, or pricked with dyed needles. The woman raised her head in the light, to display a similar pattern across one side of her face—fang-shaped zigzags across her cheek, and red ochre tendrils reaching across her face and forehead.

“What a work of art you are,” Verres breathed admiringly. “A priestess, perhaps. A seer? A valued woman among your tribe, I am sure of it. Highly regarded. Greatly esteemed. And now... here you are. Naked before me.”

Successa stared in wonder at the patterns on the woman’s body, a world away from the gentle rouges or pinched cheeks of the Roman lady. It was an entire cosmology of symbols and sigils, executed with the barbaric angles and daubs of the primitive peoples of the Euxine Sea. But Verres barely glanced at Medea’s decorations. His hands saw no ink. They cupped and caressed the taut, nervous woman’s body like any other.

“Rape is the Roman way,” Verres said in Medea’s ear. “Do you know that, little Medea? We have taken our women this way since before Rome was a city.”

Medea’s dark eyes stared unblinking into his, unfathomable. Verres felt her breath on his mouth. His hard cock bumped against the soft flesh of her stomach, leaving a gleaming trail like a snail. His free hand caressed her hip, traveling up to the curve of her breast, his fingers circling a hard nipple.

“I see you are excited, little Medea,” Verres said with some surprise. “What about me excites you, I wonder...?”

Medea’s glance darted to the doorway, where Successa the courtesan stood impatiently.

Successa let out an involuntary sigh of exasperation.

“If your company is paid for, Successa, then remain here and observe!” Verres said. “The idea of an audience amuses me.”

“I am at your command, Verres,” Successa said, trying in vain to hide a hurt tone.

“Then I command you to witness,” Verres said, smiling. “See how a true Roman man imposes his virtue upon the lower races. Watch and lea—”

Verres was cut off mid-sentence as Medea kneed him hard in the groin.

As Verres gasped in pain and surprise, his grip loosed on her hair. He folded on himself, grasping at his bruised gonads, only for his face to come into contact with Medea’s knee, forced down onto it by her hands. Verres let out an involuntary yell, keeling over onto the cell floor, but Medea had already forgotten him. Naked, she sprinted straight for the doorway, where Successa watched, frozen in surprise.

Medea grabbed Successa by the throat, her free hand clawing forward at the woman’s eyes. They spun through half a turn, until Medea kicked Successa away, back into the cell, simultaneously propelling herself out through the doorway and into the corridor.

Verres was struggling to his feet as Successa landed on top of him, sending both Romans back to the floor in a groaning heap. Successa’s dropped torch landed on her expensive, figure-hugging gown, smearing it with viscous, sticky pitch, already burning in multicolored flames.

Medea ran down the corridor, her shadow leaping large on the walls in the light of the newly kindled fires. The shrieks of the burning woman drowned out any other sounds in the enclosed space, but Medea remained focused. She paused momentarily, lost, and then looked at the scuffmarks in the sand left by the feet of her tormentors.

Medea began to sprint along the route they had taken, only to skid to a halt before another cell.

A man spoke to her, in a language she did not know.

She turned to look at him, and he rattled the bars of his cage for effect.

He said something else, but all Medea heard were spits and coughs of Aramaic.

He tried Greek instead, broken Greek, with Latin smeared upon it like dirt.

“Not slave! Not slave! Free Medea free?”

Medea smiled with only half her mouth, grabbing the bolt that held the door closed and shoving it aside. She did not even stop to open the door, darting instead to the next cell, and the next, pulling away the opened locks, and slamming their bolts aside.

The occupant of the first cell gleefully shoved open his prison and stumbled into the hallway. The hellish light from Medea’s old cell had rapidly diminished, the noise of the woman’s shrieks now reduced to whining sobs. The acrid smell of burnt hair drifted into the corridor on a pall of invisible smoke.

“Fucking painted bitch!” roared the voice of the Roman from somewhere within.

Medea peered up at the man she had just freed. He looked back at her expectantly.

“Vhat?” he said carefully, his Latin still slurred and unkempt. “Now vhat?”

Behind him, several other freed gladiators stumbled into the gloomy corridor, some still bleary-eyed, others alert and ready for action.

Medea gestured toward the staircase up to the atrium.

She chose her words carefully, as best she could.

“Kill them,” she said. “Kill them all.”

The band was in full sway, the drummer beating a rhythm like that of a galley slave master. Valgus was on top of a woman in the shallow atrium pool, thrusting into her in time to the music. Timarchides lay back on his couch, cradling the head of the girl who fellated him. Marcus Porcius humped his woman like a dog, grunting and wheezing as he clutched her haunches.

Pelorus lolled smugly on his couch, watching with a contented smile as the Gallic whore ground herself against him. He reached up to tug on her braided red hair, and was faintly disappointed when it came off in his hand. He cast the wig aside with a grumble and concentrated instead on kneading her small breasts.

Medea came out through the band, pitching the pipers into the pool, kicking the drummer headfirst onto his drum. The music came to an immediate stop, with only the cymbals playing on, clashing three last times as they bashed into the wall, each other, and then the ground. One spun momentarily like a dropped plate, coming to a swift and silent halt.

The musicians complained loudly, while the partygoers stared in blank amazement at the ferocious naked woman in their midst. The flickering firelight danced on her skin, making her alien pigments seem to writhe in sinuous whirls. The decorations on her face slid into shadows made by the curls of her hair, making it impossible to tell where the hair stopped and the skin began, as the shadows moved like snakes across her skull.

“Do you come to entertain?” Marcus Porcius asked, slapping his woman’s behind. Medea punched him in the eye.

Several diners laughed at the sight, but not Pelorus. He shoved his wigless couch-mate to the ground, stumbling to his feet.

“Who allowed her to go free?” he yelled, as the freed slaves began to pour from the same door that had permitted Medea’s entry.

“Guards! Guards!” Pelorus called, before Medea leapt right at him, propelling him to the ground. She snatched up his discarded fruit knife and plunged it into his neck. It caught on something, and Medea wrenched it free with a spray of blood. Pelorus clutched his hand to his throat, desperately trying to staunch the flow, as the gore-soaked Medea upended the nearby dining table into the pond.

Behind her came a platoon of men in loincloths, wielding what meager weapons they had managed to snatch from the house. One held a goblet in each hand. He punched with the metal cups, etching deep red welts into the head of Marcus Porcius. The other freed slaves, armed with fence posts and statuettes, clubbed their way through the dinner party in a scene of terrifying chaos.

Then the slaves came face to face with Timarchides, a towering well-muscled Greek, his skin criss-crossed with the thin white lines of forgotten battles. He stared back at them in shock and surprise, a hurt look on his face, as if they had wounded him more deeply than Pelorus.

For the briefest of moments, the escaped slaves and Timarchides stared into each other’s eyes, separated by an insurmountable gulf of liberty. But then the deadlock evaporated in a flurry of limbs, shouts and screams, as the slaves hurled themselves into the fray.

Timarchides dodged a blow from a man swearing at him in Egyptian, who was brandishing a statuette. The snatched deity whisked past Timarchides’s head, missing by mere inches. Timarchides leapt forward and grappled with both arms, forcing his assailant backward into the churning waters of the atrium pond. The man’s head met the marble poolside with a crack, and Timarchides felt the straining arms relax in his grip.

Dark-clad armored figures poured into the room—the guards from the villa’s outer grounds, their numbers increased by members of the nightwatch. With swords and clubs, they swiftly dragged the remaining slaves away from their opponents, cornering them against the far wall of the garden: three bleeding, dishevelled men, and one defiant woman. A guard flung the fifth, unconscious slave at their feet.

Timarchides willed the throbbing in his head to go away. He covered one eye with his hand in an attempt to stop seeing double. But Pelorus lay dead on the floor, surrounded by the wreckage of his last party, his throat torn open like a second mouth, his life’s blood swirling into the oily surface of the pond, flowing across the water toward the drain at the far end.

“Dozens of slaves occupy the cells below,” Timarchides said, addressing the man from the east as if he were their leader. “And yet, you five alone bring death to them all. ”

The man from the east stared back, uncomprehending, at Timarchides.

“Vhat?” he said. “No.”

“‘Vhat’ indeed,” Timarchides said. “You bray as if a fucking horse. Do you not know what you have done?”

The slave simply stared back at him.

“You repay your master’s kindness with the greatest price. His life and your own. And all other slaves in this house.”

“Command and I shall strike the blow,” the lead guard declared.

“No,” Timarchides said. “The death must be answered publicly, as Pelorus must be mourned.”

“We can kill them now,” insisted the guard, glancing anxiously at his men.

“Lock them all away,” Timarchides ordered curtly. “They shall die a slave’s death. And all shall see it.”

II

JUPITER PLUVIUS

“IT LOOKS LIKE RAIN,” GOLDEN-HAIRED VARRO SAID GRIMLY.

Spartacus looked at him and smiled. He shifted his feet experimentally in the sand of the training ground, still damp from the previous day’s shower.

“For a change?” he asked.

“Back inside, Rain Bringer,” Varro said. “I do not wish to fight in rusty armor.”

But Spartacus waited, ready, his wooden training sword and battered shield at the ready. The training space referred to simply as “the square” resounded with the clonks and smacks of wooden swords on wooden shields.

“Look to the heavens,” Varro continued. “They will soon break open.”

“As will your head,” Spartacus responded, “before it has chance to get wet.”

Varro turned pleadingly to Oenomaus, the towering African trainer who frowned down upon them like an irritated god.

“Doctore, I beg you,” he pleaded.

But the black man shook his head and stood with his arms folded, his whip twitching in his hand.

“A gladiator,” Oenomaus said quietly, “has no fear of water.”

The other fighters laughed uneasily.

“A gladiator,” Oenomaus said, his voice rising in volume, his annoyance now more apparent, “does not fear a little rain.”

Oenomaus addressed not merely the truculent Varro, but the whole gathering of warriors. The few practice fights that had been already underway had swiftly ground to a halt as the assembled fighters took the hint to stop and listen.

Oenomaus stood, his hands on his hips, at the cliff’s edge that formed one side of the ludus training ground, a vast open expanse of tantalizing freedom—at least to any man who could imitate Icarus and fashion his own wings. To mere mortals, it was a wall by another name, an empty space above a drop to certain death, and the distant vista of the Campanian hills, wreathed with clouds and glimmers of faraway storms.

“The best arenas have sailcloths drawn across the stands,” Oenomaus bellowed, “to protect the noble public from the sun’s excesses. If the weather is bad, the awnings will hold the rain from the faces of the crowd. Therefore the editor of the games, who has invested a year’s coin in their preparation, need not cancel merely for the sake of some water falling from the sky. The sailcloths do not extend over the arena itself!”

“Doctore,” Varro said humbly.

But Oenomaus was not finished.

“A gladiator fights in all weathers. He must be ready for all conditions, at the editor’s whim.” Oenomaus allowed his voice its full potential to boom. “If the editor demands that you fight on stilts, you fight on stilts. If the editor elects to clad you in the costumes of gods or heroes, you will wear those costumes and play your parts. If the editor wishes to hold games in winter on a mountainside, you will fight on ice and in snow. Is that understood?”

“Doctore!” the men chorused.

“The editor seeks new thrills and spectacles. He demands weapons and mismatched opponents. The House of Batiatus does not arrange the games. The House of Batiatus rents your flesh to any editor that will pay the price, and prepares you for victory. The gladiator is prepared for all circumstances, because if he is not, he will die without honor. Is that understood?”

“Doctore!”

“Then fight!” Oenomaus cracked his whip for emphasis, its leather tip snapping through the air scant inches from Varro’s blond curls. The noise of wood clattering on wood recommenced all around them, and Spartacus waited impassively.

Varro snarled and charged toward him. Spartacus waited calmly as the burly Roman advanced.

But then the Thracian charged in another direction, slanting away from the Roman, charging and stabbing at an invisible opponent. His lunge presented his shield arm against the charging Varro; his sword thrust outward at thin air, at the place where an opponent might be.

Varro was unable to veer to the left: such a move would have thrown him straight onto his opponent’s sword-point. Instead, he faltered, slamming obliquely into the Thracian’s shield as Spartacus wheeled and lifted his arm.

Varro was sent flying, landing heavily on his back, wheezing, the breath knocked out of him.

Spartacus lurched forward, the tip of his sword suspended a thumb’s width from Varro’s throat. The fight was over before it had even begun.

Laughing, Varro raised two fingers in supplication, and the two men waited for an imaginary signal from an absent audience. They glanced up at the balcony, where a lone figure stood motionless, her robes fluttering in the breeze.

On a better day, Lucretia, wife of Batiatus, might have played along and given the signal for manumission. But although she stared right at the two men, she saw nothing. Her mind was elsewhere.

Lucretia watched from the balcony through eyes reddened by weeping, her expression unreadable. She did not smile at Varro’s protestations of Thracian cheating, nor did she stay to watch as the Roman clambered to his feet for a rematch. She turned slowly and walked back inside the house, her ears deaf to the continued din of wooden swords on wooden shields. She swept down a long corridor lined with the busts of former gladiators, stone memories of days past.

“Good news after bad!” Quintus Lentulus Batiatus cried, brandishing a scrap of damp papyrus.

Lucretia did not even acknowledge her husband’s excitement, breezing past him into the shrine of the household gods. Too late, she realized there was no other exit. She was cornered.

She turned to meet her husband, straining to smile.

“Word sent that Pelorus does not require us for the Neapolis games,” Batiatus continued.

“After such preparations—” Lucretia began.

“For a gubernatorial celebration, yes. Plans have been revised.”

“We do not bend to change like Macedonian whores.”

“Events beyond the control of good Pelorus.”

“What events—?”

“That of death. Death of our good friend Pelorus himself at the hands of his own slaves,” Batiatus said with a grin.

For a moment, the house was silent, but for the tinkling of a distant fountain, and the muffled footsteps of a slave going about her duties. Lucretia blinked.

“I can see the loss grieves you,” she said eventually.

“My heart breaks,” Batiatus smirked, “at the loss of coin.”

“The Neapolis games were our last booking this month. And our Prince of Mars lies wounded...”

“And yet I proclaimed good news, as well.”

“How can you jest when our best gladiator fights for his life?”

“Crixus?” Batiatus said. “It is Spartacus who is the Champion of—”

“Crixus will soon rise to reclaim what he has lost!” Lucretia shouted, louder than she had expected.

Batiatus shuffled uneasily.

“My heart is touched,” he said, “that you are moved to such concern for our business and our slaves.”

“And where is this good of which you spoke,” Lucretia muttered, fussing with some of the smaller statuettes among the Batiatus household gods. She picked up the figure of her late father-in-law and gazed at it, her fingers tracing the face of the small metal token. She then carefully set it back down among the other imagines, facing away from its companions, as if lost or addled.

“There will be funeral games, Lucretia,” Batiatus said. “And the editorship requires gladiators beyond the limits of the town.”

“For what reason?”

“The House of Pelorus is finished. Those slaves will suffer execution. And then even the killers will be killed.”

“A terrible thing, to be betrayed by ones so trusted,” Lucretia said, sucking in air through her teeth.

She stepped from the shrine back to the green-walled atrium, her husband scurrying to keep up with her. She looked around for some sign of her slave Naevia, hoping to busy herself on some ladies’ business that Batiatus would find tedious.

“A terrible thing for Pelorus, but a thing of opportunity for us!” Batiatus protested, slapping the papyrus for emphasis. “We only need send a few gladiators, and the very nature of the event assures them all of victory.”

“Do you not think this one last insult from Pelorus? To force you to make haste across Campania on some pointless enterprise of maintenance, little better than sweeping up behind horse? Has that man not cost you enough time?”

“We have but time to waste, beloved. All Capua is in mourning for the... tragic death of Ovidius. Preventing indulgence in the celebration of our recent victory until nine long days have passed.”

“And you would pass day in other town, until our own offers warmer clime?”

“My thought exact. Let Spartacus, Barca and a few promising recruits take to the sun, far from the cloud of Ovidius and the pale of his death.”

“All to scrape coin?”

“A much needed infusion. And, of course, the chance to bid proper farewell to good Pelorus.”

“And what of it to you, if his funeral passes without remark?”

“I care not a shit for his departure from this world,” Batiatus said. “But let us show decorum befitting of this noble house and lend grace to his disgraced house.”

“Quintus, must we?”

“We were mutual hospes! His threshold was as our own, should we ever have crossed it.”

“An opportunity of which we seldom availed ourselves. Nor he with us.”

“He shall surely be laid to rest before the calends of October, but three days’ hence!”

“Then you had best depart immediately. Lest he be set aflame before you arrive.”

“Lucretia, please!”

“He resides in Neapolis, Quintus! Or had you forgotten?”

“Since when do you not care for Neapolis? And the opportunity it allows to part with coin? To say nothing of the sea air,” he protested.

“It smells of rotten eggs.”

“The friendly local citizens?” Batiatus suggested.

“Quarreling Greek refugees and fishwives.”

Something flashed in the sky, like the glint of a sword in the sun. Batiatus paid it no heed, his eyes locked on his wife, entreating Lucretia to offer some iota of spousal support.

“The broad sweep of the bay. Those sparkling waters,” he pleaded.

“Muggy in summer. Choppy in winter.”

“And here we are, swiftly approaching harvest and equinox! An auspicious occasion to visit.”

Batiatus paused, a broad, winning smile on his face begging his wife to acknowledgment. As if to spite him, there was a distant rumble of thunder on the Capuan hills. A drip of errant drizzle dashed against his cheek, then another.

Lucretia held out her hand inquisitively, craning her head out into the open space of the atrium. She stared up at the low, gray clouds overhead.

“Is that rain?” she mused.

“Impossible,” Batiatus replied.

Behind him, the waters of the atrium pond showed dots of activity. Points of water flecked on the previously calm surface, the impact of unseen raindrops. Across the courtyard, Lucretia saw silent flecks of rain dashing against the upper walls, freckling the brown clay plaster into a deeper shade of red.

There was another flash of lightning, and a crackle of thunder almost immediately after it.

Batiatus glanced behind him in annoyance, in time to see the drizzle shift to a downpour, churning the waters of the atrium pond into a rough sea, spattering the green inner walls a murky dark gray. Batiatus shivered involuntarily, and realized that the lower hem of his toga was already drenched.

“Jupiter’s cock!” he shouted, snatching his robe from its puddle.

Lucretia turned from the rain’s chill, gliding back toward the antechambers of the house.

“Jupiter Pluvius, the divine bringer of rain, himself counsels a roof over your head, Quintus,” she called, not looking back at her husband.

“All summer I prayed only for rain,” admitted Batiatus. “Now I tire of it.”

“Then rest indoors and wait for such storms to pass.”

“This storm? It is but trifle,” Batiatus declared.

“As is all unwelcome change. Be it by men or gods.”

Their upraised voices echoed through the house, but did not travel to the outer gardens. The rain saw to that, pelting onto the Capuan clifftop with increasing volume, until it drowned out all other sounds in a relentless rattle. It pattered on the leaves of the formerly parched trees. It drummed on the cracked ground. It tapped an irritating, unceasing tempo on the waxed tarpaulin of the litter that approached the house of Batiatus.

The four bearers, one shouldering each end of the two carrying poles, struggled with each step to maintain their footing. Feet used to the reliable, measured flagstones of the Appian Way scraped and slipped on treacherous dips and uncleared tree-roots. Three of the slaves did not even look up, crouching their heads beneath their sodden hoods and concentrating merely on putting one foot in front of the other. Only the lead bearer, standing at front-right, exposed his head to the rain, squinting through the storm in case of oncoming traffic.

The litter and its bearers had no other company on the remote track. They plodded on through the rain, their pace picking up as the welcoming lights loomed nearer. The cargo was light, barely noticeable to accomplished porters, such that when the leader called halt, the litter was raised off their shoulders and lowered to the ground with ease.

Within the courtyard of the Batiatus villa, shadowy figures scurried to the portal. The occupant of the litter stirred, placing a foot gingerly on the damp ground. A figure substantially smaller than the vast man’s cloak that wrapped it scampered through the storm toward the entrance of the house itself, and the indistinct sound of a couple in the middle of an argument.

“It is inconvenient,” Lucretia said.

“Inconvenient!” Batiatus yelled in response.

He inhaled sharply through his teeth, raising his arms up in exasperation at the walls around him. He glared hotly at a wall of painted finches and songbirds, and thought meanly of roasting them on spits.

“It is inconvenient that my prize gladiator lays pierced with hole the size of Rome’s Cloaca Maxima, unable to enter the arena any time soon.”

“I realize that,” Lucretia said carefully. “It grieves me. It grieves me sorely that Crixus is—”

“It is inconvenient,” Batiatus interrupted, “that this ludus has but one opportunity to secure coin in coming month and it lays forty-five thousand paces from this place, in a miserable, stinking, boy-loving, infestation of Greeks!”

“I thought we liked Neapolis?” Lucretia said with the faintest of smiles.

“I despise Neapolis!” Batiatus spat. “A filthy backwater population brimming with smug merchants, pushy beggars, and unruly street urchins, built upon slope toward sea. Every journey a torment of travel uphill, through fucking stone stairways.”

“Surely you must travel downhill at least half the time, beloved?”

“And yet, all directions lead uphill.”

“Now who defies reason?”

“Pelorus was a dear friend,” Batiatus said.

“You loathed each other,” Lucretia responded.

“As siblings squabble over pets, we tussled over gladiators. Though given predilections of my Capuan colleagues, my occasional auction-block competition with Pelorus seems now the very pinnacle of amity.”

“Still, no reason for my involvement in your farewells.”

“All of Neapolis society will be there.”

“I care not.”

“Pelorus shall have in death what he never had in life. Accord as a man of wealth and virtue. Mourners from the patrician class. A funeral fit for a high-ranking Roman citizen.”

“I repeat. I care not.”

“Pelorus will not be regarded as mere lanista. Important people shall celebrate his life, Lucretia. Important people.”

“And you?”

“Shall be seen as dear friend to the departed, by his other friends. For which I shall require the presence of my wife.”

“You will find that Neapolis has plenty that can be hired for service.”

There was a shadow in the doorway. A slave had approached, swiftly and silently, as protocol demanded.

“What is it, Naevia?” Lucretia said.

“Apologies, domina, but there is a visitor,” the young girl replied, eyes lowered to the floor.

Naevia got no further before the subject of her message caught up with her. A figure appeared behind her, wrapped in a coarse cloak, dripping water on Lucretia’s clean flagstones. Underneath the cloak, there was the hint of green Syrian silks, and dainty, pedicured toes.

“Pardon this intrusion,” a female voice said, lifting her veil to reveal flaxen blonde tresses, coiled into sodden ropes by the rain. Cheeks usually concealed beneath Tyrian rouge were now flushed with their own glow, with specks of dislodged kohl like ashen tears above an exhilarated smile.

“Ilithyia!” Lucretia exclaimed with exaggerated, mannered delight. “I thought you to be in Rome.”

“Such was my hope,” Ilithyia said, pushing her wrap into the hands of Batiatus as if he were no more than a cubiculum slave.

“But muddy tracks and tired bearers conspired to find me here,” Ilithyia sighed deeply, as if it were the end of the world, “scant steps from your yard and your doors.”

“It pains me that we cannot offer you covered walkway,” Batiatus said, directing his eyes heavenward, “under which to arrive more comfortably.”

“Quite so,” Ilithyia said.

“Perhaps decorated in gold,” Batiatus continued to Lucretia under his breath, “and with couches every few paces that you might take your rest.”

“I thought I might have to walk all the way to Atella to find proper lodging, one closer to civilization,” Ilithyia continued, oblivious.

“Civilization?” Batiatus muttered.

“We are delighted to receive you,” Lucretia said, shooting a sidelong glance at her husband.

“I cannot presume to impose,” Ilithyia said. “After all, we are not mutual hospes. I cannot simply turn up at your door—”

“Yet here you are!” Batiatus smiled through gritted teeth.

“Our house is your house,” Lucretia interjected swiftly. “Naevia will see you given proper quarters.” She glanced at her slave to ensure that the message was received.

“My bearers shall bring my impediments from the litter,” Ilithyia said, following Naevia from the room. “Then, we shall drink and talk of scandalous things!” Ilithyia chuckled conspiratorially, and then was gone.

Batiatus waited, seething, as Ilithyia’s footsteps receded. He bundled up her cloak and threw it contemptuously into a corner, before wheeling on his wife to hiss in suppressed rage.

“Even in accepting our hospitality she shits on our name.”

“We are lucky to hear her speak it.”

“This is our home. We were spreading myrrh on our lentils when the Romans were still running around the forests sucking off wolves.”

“Suckling, Quintus. Ilithyia is giddy with the glory of Rome. She speaks without thought.”

“Oh, she thinks. She thinks all too carefully. Every word carefully placed to cut us down. She forces her way into our house—”

“Where she is very welcome. She is an emissary of Rome’s great and good.”

“So she keeps saying.”

“She is a doorway to aediles and consuls. She has the ears of men of power.”

“For herself. Not for us, as we are not hospes. A point she made certain to make.”

“A matter merely of protocol and politesse.”

“If you were to knock on her door in Rome, with Deucalion’s deluge pouring out of the sky, with Neptune himself pissing on your head, she would order the gates slammed shut in your face. We are not fit to be accorded hospitality in her home, yet she thrusts herself upon ours as if tavern in—!” Batiatus suddenly stopped speaking, his eyes wide in surprise.

“What is it?” Lucretia asked, peering behind her, in case her husband had seen a rodent or a spider.

“Atella,” Batiatus said. “She journeys to Atella.”

“And?”

“It is five hours’ march to the south.”

“Yes, Quintus. A fact known to all.”

“On the road to Neapolis!”

Those gladiators who had shields held them over their heads to keep off the rain. Those who did not did the best they could with the flats of wooden swords, or lifted helmet visors. They stood, intently, watching two lone gladiators who stood waiting in the training ground. The storm pelted every man with rain, but none voiced a word of complaint.