Terzopoulos Tribute Delphi E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Verlag Theater der Zeit

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This book collects the contributions to the international conference on the theater of Greek director Theodoros Terzopoulos, held in Delphi, Greece, in 2018. Terzopoulos, who developed an internationally acclaimed contemporary form of ancient theater with his own method, has made a deep impact with his work on both theater theory and practice as well as on the research of its foundations in different cultures. Contributors include Hélène Ahrweiler | Afroditi Panagiotakou | Erika Fischer-Lichte | Etel Adnan | Anatoly Vasiliev | Eugenio Barba | Freddy Decreus | Frank Raddatz | Dikmen Gürün | Vasilis Papavasileiou | Eleni Varopoulou | Daniel Wetzel | Jaroslaw Fret | Blanka Zizka | Maria Marangou | Kalliope Lemos | Konstantinos Arvanitakis | Gonia Jarema | Dimitris Tsatsoulis | Savas Patsalidis | George Sampatakakis | Penelope Chatzidimitriou | Despoina Bebedeli | Tasos Dimas | Savvas Stroumpos | Avra Sidiropoulou | Johanna Weber | Panagiotis Velianitis | Ileiana Dimadi | Kim Jae Kyoung | Sophia Hill | Aglaia Pappa | Dimitris Tiliakos | Marika Thomadaki | Niovi Charalambous | Özlem Hemiș Katerina Arvaniti | Paolo Musio | Kerem Karaboga | Yiling Tsai | Lin Chien-Lang | Justin Jain | Li Yadi | Przemyslaw Blaszczak | Mikhail Sokolov | Rustem Begenov | Juan Esteban Echeverri Arango

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 336

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Theodoros Terzopoulos, born in Makrygialos in Northern Greece in 1945, studied acting in Athens. Between 1972 and 1976 he was a master student and assistant at the Berliner Ensemble. Returning to Greece, he worked as director of the drama school in Thessaloniki. In 1985 he founded the theatre group Attis, which he has led since then. From 1985 to 1988 he was also Artistic Director of the International Meeting of Ancient Greek Drama in Delphi, which included participation from Heiner Müller, Marianne McDonald, Tadashi Suzuki, Robert Wilson, Andrei Serban, Wole Soyinka, Min Tanaka, Yuri Lyubimov and Anatoly Vasiliev. He was a co-founder of the International Institute of Mediterranean Theatre and has been Chairman of its Greek Committee since 1991 and of the International Committee of Theater Olympics since 1993, for which he has conceived events in Delphi (1995), Shizuoka (1999), Moscow (2001), Istanbul (2006), Seoul (2010) and Beijing (2014), Wroclaw (2016), in 22 cities across India (2018), Toga, Japan, and St. Petersburg (2019). Since the late 1970s, he has continuously developed an individual, heavily codified, intercultural theatrical language. Guest performances of Attis Theater and workshops on Terzopoulos’ working methods take place throughout the world. As a guest director, he has directed ancient tragedies by Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, as well as operas and works by important contemporary European writers, in theatres in Russia, the USA, China, Italy, Taiwan, Germany and elsewhere.

TERZOPOULOSTRIBUTEDELPHI

Imprint

Terzopoulos Tribute DelphiEdited by Attis Theatre

© 2021 by Theater der Zeit and Attis Theatre

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopied, recorded or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Verlag Theater der ZeitPublisher Harald MüllerWinsstraße 72 | 10405 Berlin | Germany

www.theaterderzeit.de

Editor: Attis Theatre, Athens, Greece (www.attistheatre.com)

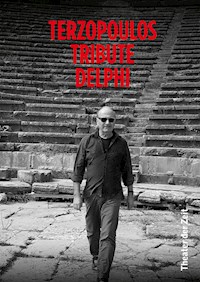

Cover photo: Johanna Weber

Translation: Articles by Anatoly Vasiliev, Vasilis Papavasiliou, Despoina Bebedeli, Tasos Dimas, Aglaia Pappa, Panagiotis Velianitis, Maria Maragkou, Eleni Varopoulou, Marika Thomadaki translated from the Greek by Maria Vogiatzi.

English language editor: Penelope Chatzidimitriou

Copy Editor: Thomas Irmer

Design: Gudrun Hommers

ISBN 978-3-95749-400-9 (Paperback)

ISBN 978-3-95749-401-6 (ePDF)

eISBN 978-3-95749-414-6

TABLE OF CONTENTS

GREETINGS

Hélène Ahrweiler, President of the Administration Council European Cultural Centre of Delphi, Greece

Afroditi Panagiotakou, Director of Culture, Onassis Foundation, Greece

Erika Fischer-Lichte, Professor of Theatre Studies at Freie Universität Berlin, Germany

Etel Adnan, Writer, Painter, Lebanon/ France

TERZOPOULOS’ POEM

MASTERS – DIRECTORS – ACTORS – ARTISTS

Anatoly Vasiliev, Director, Russia, The Return

Eugenio Barba, Director, Italy/ Denmark, No Beauty without Rules, no New Beauty without Breaking the Rules

Vasilis Papavassiliou, Director, Greece, Theodoros, a Legacy with no Borders

Blanka Zizka, Director, Artistic director, The Wilma Theater, USA, Theodoros Terzopoulos at the Wilma Theater in Philadelphia

Daniel Wetzel, Director, Rimini Protokoll, Germany, Curious Beasty Theo Boy

Jaroslaw Fret, Director of the Grotowski Institute and of Zar Teatr, Poland, Wrestling with Memory

Despoina Bebedeli, Actress, Cyprus, The Eye of Dionysos

Sophia Hill, Actress, Greece, The Body at the Anti-chamber of Death

Tasos Dimas, Actor, Greece, The Time of Grief

Aglaia Pappa, Actress, Greece, Alarme – Amor: the Evolution of an Actor Working with Theodoros Terzopoulos

Niovi Charalambous, Actress, Cyprus – The Liberating Method

Panayiotis Velianitis, Composer, Music teacher, Greece, The Memory of Sound

Dimitris Tiliakos, Baritone, Greece, The Wanderer and his Shadow

Kalliope Lemos – Sculptor, Installation artist, UK, A Synthesis of Antitheses

Maria Marangou – Art critic, Artistic director of the Museum of Contemporary Art of Crete, Greece, When Malevich meets Dionysos

Johanna Weber, Photographer, Germany, The Dismemberment of Dionysos

TEACHERS OF THEODOROS TERZOPOULOS’ METHOD “THE RETURN OF DIONYSOS

Savvas Stroumpos, Actor, Director, main teacher of the method, Greece, Corporal Reflections on the Method of Theodoros Terzopoulos – The Question of the Method.

Paolo Musio, Actor, Italy, Here, elsewhere, on the border: where I am when I am on stage with Attis

Kerem Karaboğa, Actor, Professor, Department of Theatre Criticism and Dramaturgy, Faculty of Letters, Istanbul University, Turkey, The Acting Method of Terzopoulos as a Means of Confrontation with our Age of “Total Decay”

Justin Jain, Acting company member, Wilma Theater, Professor of Acting, University of Arts, Philadelphia, USA, The Universal Body: Exploring the Methodology in the United States

Li Yadi, Acting Teacher, Beijing Central Academy of Drama, Director, China, An Extraordinary Journey of Attis

Przemyslaw Blaszczak, Actor, Grotowski Institute, Poland, My Experience of the Method of Theodoros Terzopoulos

Rustem Begenov, Actor, Director, ORTA Center, Kazakhstan, The Method of Theodoros Terzopoulos: my Experience as an Actor and Assistant Director

Lin Chien-Lang, Theatre performer, Taiwan National Theatre, Theatre Academy, Taiwan, A Journey to the Unknown: My Reflection on the Return of Dionysos

Yiling Tsai, Actress, Taiwan National Theatre, Lecturer, Department of Drama, College of Performing Arts, National Taiwan University of Arts, Taiwan, My Journey to the Unknown

Mikhail Sokolov, Actor, Electrotheatre Stanislavski, Russia, The Experience of the Bacchae

Juan Esteban Echeverri Arango, Actor, Colombia, The Vibration, a Journey into a Primitive Memory

THEORETICIANS

Savas Patsalidis, Theatre Professor, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece, Theodoros Terzopoulos’ Eco-Theatre and Tragic Landscapes

Freddy Decreus, Professor Emeritus, University of Ghent, Belgium, A Theatre of Energy, a Theatre of Consciousness

Frank Raddatz, Author, Dramaturg, Germany, Theodoros Terzopoulos’ Theatre of Verticality

Eleni Varopoulou, Theatre Critic, Author, Translator, Greece, Theatre as a Translation: Heiner Müller and Aeschylus by Theodoros Terzopoulos

Konstantinos Arvanitakis, Professor of Psychoanalysis, McGill University, Montreal, Canada, Primal Phantasies and the Unrepresentable in the Work of Terzopoulos

Gonia Jarema, Professor, University of Montreal, Canada, The Voiceless Voice in the Work of Theodoros Terzopoulos

Dimitris Tsatsoulis, Semiotics of Theatre & Theory of Performance/Professor Emeritus, University of Patras/ Theatre Critic, Greece, Glossolalia: from Artaud’s “langage universel” to Terzopoulos’ “Nuclear Rhythm of the Word”

George Sampatakakis, Ass. Professor of Theatre Studies, University of Patras, Greece, Eros and Thanatos: the Aesthetics of Enchantment in the Theatre of Terzopoulos

Penelope Chatzidimitriou, Dr. in Theatre Studies, Instructor in MA in European Literature and Culture, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece, (Un)livable, (Un)grievable, (Un)mournable Bodies: Violence, Mourning and Politics in the Theatre of Theodoros Terzopoulos

Marika Thomadaki, Professor of Theory and Semiology of Theatre, University of Athens, Greece, Energetic Theatricality and Creative Forms in Theodoros Terzopoulos’ Performances

Iliana Dimadi, Dramaturg, Onassis Cultural Center, Greece, Attis Theatre and the Need for “another” Critical Language

Özlem Hemiş, Assistant Professor, Kadir Has University, Istanbul, Turkey, The Idea of the Tragic in Alarme / Amor / Encore

Avra Sidiropoulou, Ass. Professor at the M.A. Programme in Theatre Studies, Open University of Cyprus, Cyprus, Towards a Poetics of Communality: Theodoros Terzopoulos’ Staging of Tragedy in the 21st Century

Katerina Arvaniti, Ass. Professor, Department of Theatre Studies, University of Patras, Greece, Prometheus Bound Directed by Theodoros Terzopoulos

Dikmen Gürün, Professor of Theatre Studies M.A. Programme, Kadir Has University, Istanbul, Turkey, Reception of Theodoros Terzopoulos’ Works in Turkey

Kim Jae Kyoung, Ass. Professor, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, Korea, Theatre Olympics and Terzopoulos’ Artistic Vision

PROGRAMME OF THE TRIBUTE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

GREETINGS

HÉLÈNE AHRWEILER

President of the Administration Council European Cultural Centre of Delphi

An inner and long-lasting relationship links the European Cultural Centre of Delphi with the work of Theodoros Terzopoulos. For a long time, the questions and concerns of this great director and outstanding man of the theatre were also the concern and anxieties of the Centre.

Delphi has always been a perfect setting for the presentation of all the remarkable performances of Theodoros Terzopoulos either as research experiments or as proposed solutions. Their acceptance by the audience, as well as by experts and critics, has always been encouraging and often very enthusiastic.

I would also like to note that Theodoros Terzopoulos was, for many years, the artistic director of the emblematic meetings of Ancient Drama organised by the European Cultural Centre of Delphi.

This year’s tribute is organised as a small token of this longstanding friendship between Theodoros Terzopoulos and the Centre of Delphi. “The Return of Dionysos” is the main event of the Centre’s artistic programme for this year. Participants are distinguished foreign and Greek academics, researchers and artists whom I wish to warmly thank for their contribution.

The tribute includes an international symposium, a demonstration of the method of Theodoros Terzopoulos, a photographic and a sound installation. The crowning event is the performance The Trojan Women by Euripides, directed by Terzopoulos, at the Ancient Theatre of Delphi.

The “Return of Dionysos” is made possible thanks to the Onassis Foundation’s generous contribution. The cooperation of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Phokis has been invaluable. Let me also remind you that 2018 has been declared “Year of the European Cultural Heritage” and Delphi shares these celebrations.

The tribute to Theodoros Terzopoulos is organised, despite the very limited financial resources of the Centre of Delphi, thanks to the dedication and the high professional quality of the few associates of the Centre. I wish to thank and congratulate them as President of the European Cultural Centre of Delphi.

AFRODITI PANAGIOTAKOU

Director of Culture, Onassis Foundation, GREECE

The body is a very dangerous thing. Myths are, too. And Theodoros Terzopoulos’ theatre is a theatre wrought from myths and bodies; a theatre beautiful for reasons that transcend aesthetic categories. “Beauty lies in change. That’s the intoxication of things. I always seek a clash, a rupture. I’m not interested in things resting peacefully in their beauty”, he says.

At the Onassis Foundation, we often say we have no interest in beauty per se. Meaning that showing beautiful things to the world just isn’t enough. Because we are not striving simply to produce culture; we want to change culture. Change means conflict. Pressing on ahead without a safety net is liberating; it can also be self-destructive – unless the freedom comes with knowledge, specifically well-founded knowledge.

A forward-thinking man, never afraid of conflict, Theodoros Terzopoulos is more than the internationally celebrated director with 2,100 performances to his credit. He laid the foundations of an actor training method that places its trust in the body, in myth and ritual, in Dionysos. For the god of theatre, of life and death, eternal transformation and conflict, always returns to the Attis theatre.

Given his oeuvre and his career, you could almost say that the Onassis Foundation’s entire cultural mission over the last four decades is encapsulated in Theodoros Terzopoulos: presenting Greece at its best, here and everywhere, with humankind and society at its core and art as an engine of change. That’s what Theodoros Terzopoulos does. His work comprises a theatre education in its own right; his method is an act of liberation; his axis, around which the works revolve, is people – always people.

And we are at his side. As a gesture, our support for this Tribute to Theodoros Terzopoulos at Delphi is especially symbolic. The first step in a long-term relationship. Because we too have learned a great deal from Theodoros Terzopoulos. Have learned too from what he is doing here: connecting people with one another, connecting generations, making clear to us all that the very future’s future is in fact the present moment. Our job then is just to talk with one other, to follow his guidelines, all of which are rooted in learning how to listen, how to give our full attention. I consider myself lucky because I have already seen Terzopoulos’ future, my children have seen Terzopoulos’ performances, and that means something for the generations to come. And some of us may sometime meet again and say: “We first met at Delphi, oh yes, with Terzopoulos, oh yes…”

PROF. ERIKA FISCHER-LICHTE

Professor of Theatre Studies at Freie Universitat, Berlin, GERMANYDirector of the International Research Centre for Advanced Studies on ‘Interweaving Performance Cultures’, GERMANY

Dear Theo,

I am so deeply sorry that I cannot participate in this wonderful event, held in your honor. As you know quite well, I owe some of my deepest and most important experiences in theatre to your productions. The first was the Bacchae and the last, as we both remember, Prometheus in Wroclaw.

The title of this conference is The Return of Dionysos and this is not by chance. As we both know, as a child, Dionysos was dismembered by the Titans and then Zeus put together the fragments of the dismembered body. This is so meaningful for your theatre. In its center is the human body. Since Helmuth Plessner, we are all very much aware of the fact that we are a body, that we are body subjects. On the other hand, we have a body, a body that we can instrumentalize and put to very different kinds of use. The body-subject and the body-object are very closely related to each other. Everyone grows up in a particular culture and gains quite a number of different body techniques. Body techniques that are linked to this very particular culture and determined by it. For the actors, moreover, techniques are shaped by the special kind of training. So, what you want the actors to do is to unlearn the specific body techniques they have acquired so far. We can say that you ask them to dismember their body and then to put together the fragments piece by piece in a new way, creating a completely new body-object. But since the body is nothing without the body-subject and because they influence and are related to each other, this way also, another body-subject comes into being. This is in fact, the journey which Dionysos made in a certain respect.

This is not only a method that shapes a new body, body-subject and body-object, but is also one which forms the basis for the co-operation of actors hailing from very different cultures. Because all of them have to do the same. But what comes out of that, the result, is by no means a homogeneous body. They do not do the same, although they have undone the formal body-object in a very similar way and acquired a new one, as well as a new body-subject. This is one of the great aspects of your work with actors: that actors hailing from such different cultures and performance cultures are able to collaborate with each other in such a fruitful and promising way.

This is also the basis for another thing, which is particularly important to me. That this is a new approach to Greek tragedy. As we all know, since the late nineteenth century, people in Greece, in Germany and in Europe in general, were more or less convinced that Greek tragedy is “universal” and therefore transmits universal meanings and values. This is, of course, of great doubt to us. What happens now is that your method, when you apply it to Greek tragedy, “universalizes” Greek tragedy in a way that is completely new. Because it is based in the human body and springs from the human body. The link between the body and the word, the logos, is a completely new one. The logos is not something inscribed into the body, but which comes out of the body, grows from the body, emerges from it and then through the breath, which is also a part of the body, is conveyed to the world and onto the spectators. One might call this a universal proceeding, but it has nothing to do with the universalism, cherished so much since the eighteenth century.

Theo, I want to thank you very much for the experience you allowed for with your productions, for the new insights you enabled me to make into theatre as well as into Greek tragedy. I hope very much that you will continue to create new works in this way, but of course in very different manners, as you used to do and that I shall also have the opportunity in the future to witness them. So, once more, congratulations on this great event, which you more than deserve and best wishes for your future projects.

ETEL ADNAN

Writer, Painter, LEBANON

I’m deeply sorry that I cannot attend the tribute to Theodoros; a tribute he mostly deserves. I love his job because he looks to the East. It is authentic and, while it is modern, it is deeply rooted in the tradition. It unites the old with the new, creating an authentic form. When you listen to Theodoros singing oriental melodies, you realize his relationship with the tradition. You feel that in his work nothing ends, it goes on forever, because his work focuses on the nucleus of the body.

I do not visit Greece often, but Theodoros is always in my mind, I love him very much, because he is authentic and his work is collective and profound. I love him, as if we have known each other for a long time. When we meet, I speak Greek better. His voice reminds me of my father’s voice and I am moved.

THEODOROS TERZOPOULOS’ POEM

You now arrive,and I am eagerto participatein your beautiful celebration.

You now arriveto remind methat the Word is the Earthand that Knowledge is Consciencethat Passion is its Removaland Harmony is its Contradiction.

You now arrive at the homelandand I linger around youeager to participate in your beautiful celebration.

Crash the Mirror, you say,And the fragments willgive birth to a new image.

Looking in your eyeshallucinations possess methe journey of Transgression begins.

You arrive now when I am readyTo offer my Bodyto the sanctum of the Uncanny!

An evening in DelphiWhen the mountains are bleeding.

Theodoros Terzopoulos, Erdogan Kavaz at the Ancient Theatre of Delphi, The Trojan Women rehearsal (photo Johanna Weber)

MASTERS DIRECTORS ACTORS ARTISTS

The Return

ANATOLY VASILIEV

Director, RUSSIA

I will speak about Terzopoulos and my generation – since we are almost the same age. I first came to Delphi in 1995, invited by him. Our acquaintance and relationship have been decisive for my relation with Greece. For twenty-three years now – from 1995 until now – I have been feeling connected with Greece.

I saw his performances in Delphi in 1995 and it was a formidable experience. The most striking memory I have was walking through the night, climbing a mountain and then suddenly beholding the amazing view of the ancient theatre of Delphi and seeing the performance. It was a remarkable performance, with a new, utterly different expressive language. I had never seen such a performance. For the first time I felt that I had been transferred to an ancient world and that experience was stunning. I was thinking that if this world always existed, if our European civilization maintained fragments of this ancient civilization, then we would be able to talk about a great culture. Instead, now we only have the European culture and I, as a Russian, am a part of that culture. We have not maintained the tradition of the ancient Greek theatre, unlike the Japanese or the Chinese who have preserved theirs despite the revolutions. And then, along with my enthusiasm, I felt sad because I realized that it required a human feat, the feat of a director and a small troupe of actors, to represent it and say: “This exists. Embrace it. Embrace us.” And the most important: “Preserve it.”

Then, I visited Delphi many times and there it was decided that Moscow would host the 3rd Theatre Olympics. Once again, I owe this to Theodoros. To be precise, I owe a lot to Theodoros. On the occasion of the Theatre Olympics, we had proposed an adventurous idea to the Moscow government: to build a new theatre building, based on my theatre concept and the designs of a fellow architect, scenographer and artist, who also knew Delphi very well. But to make this happen we needed money and the support of the Moscow government; and we only had two years until the Theatre Olympics. So we needed an eminent and prestigious person to support this endeavor and this person was Theodoros. We all sat around a big conference table along with the Moscow government, and then Theodoros stood up and said that he, as a Greek director and the Chairman of the International Committee of Theatre Olympics, was convinced that the government should build a theatre for Vasiliev. And Theodoros’ word had a great impact in Moscow.

Here I would like to make a parenthesis to say that I speak about Theodoros not only on my behalf but also representing Yuri Lyubimov, who had visited Delphi several times and was a friend of Theodoros and Alla Demidova, who has played in many of his performances and sends her greetings to Theodoros, this great man.

Well, the theatre was built and its architecture was based on the ancient Greek principles. There was not a single Italian stage in the theatre. I remained in this theatre for only a few years, namely from 2001 to 2006. The Moscow government gently asked me - actually, not only gently but ordered me - to leave the theatre and the city. I was not angry, I do not hold any grudge against the government, but I said farewell to Moscow forever.

If you ask why this happened, it happened because of my devotion to the ancient theatre. I started working on the ancient theatre, the internal drama, metaphysics, the ancient dramaturgy. My last premiere in Delphi was Homer’s Iliad. I also presented here Heiner Müller’s Medea Material.

It was then that the Moscow government claimed that this approach was not new; this was not theatre for the people. And yet, this is the most powerful idea. This is what Theodoros, Grotowski, Barba and I have been working on. So, is this theatre for the people or not? How could I explain to the government that this is real, authentic theatre for the people? Everything else is bourgeois theatre. What do we mean when we say “people” and “bourgeoisie”? These two concepts are not identical.

Time passed by and Theodoros came once again to Moscow, this time invited by the Electrotheatre Stanislavsky. Here, I would like to make one more parenthesis to say that I started my career at the Moscow Art Theatre and continued at the Electrotheatre Stanislavsky. The artistic director of Electrotheatre, Boris Yukhananov, is a former student of mine. He invited Theodoros to direct for this stage, where I had also directed in 1977 and 1981. So, I went to the theatre to see the Bacchae directed by Theodoros with Russian actors. And I was happy to see the return of Dionysos.

Before closing my short speech, I would like to thank Theodoros Terzopoulos not only because he is an exceptional director – which is the topic of our meeting today – but also because he is a great person.

Thank you very much.

No Beauty without Rules, no New Beauty without Breaking the Rules

EUGENIO BARBA

Director, Italy / Denmark

On my way to this conference, I met a flock of birds who asked me: “Are you going to Delphi, the city of oracles? Be careful, do not listen to them, because they don’t bring luck. And, please, deliver this message to Theodoros Terzopoulos”.

(Julia Varley delivers the message singing bird sounds)

I will translate their message.

There is one aspect in Theodoros Terzopoulos’ work which is peculiar. It has nothing to do with the professional, but it is fundamental in shaping cultural surroundings. I am talking about his need to create shelters. He creates and organizes these shelters within institutional frames and names them with fine-sounding titles, like the International Meetings of Ancient Theatre in Delphi, or the International Institute of Mediterranean Theatre, or the Theatre Olympics, or the International Meeting of Ancient Theatre in Sikyon. But what does he really do? He stresses out a very essential dimension in our profession, which is the process.

When we speak about theatre, we always refer to the audience, the spectators, the external, the visible part of our profession - the results. However, the most difficult, the hardest part for the most of us, is the process: how to be able to transform an idea, a heritage, a legacy, a text – symbols written on the paper - into something which becomes perceptible signs – intonations, silences, gestures, immobility – provoking a personal reaction in the spectators’ memory, senses and neural system. So these meetings about the actor’s individual creative process, for which Terzopoulos has his own vocation to organize them, are extraordinary events in contemporary theatre. He is an exception and I want to thank him for this.

Terzopoulos belongs to the kind of people in our profession, who ask themselves “what is theatre?” I don’t know what his definition is, but I believe a possible answer could be: “theatre is the men and women who do it”. What does it mean practically? It means to work individually with every single actor and find a way to make them a source of attraction/reflection for each single spectator. When we think of the origins of the systematic work with the actor, when we look back at the beginning of the last century and refer to the leading theatre reformers, we discover two ways which were developed, in order to stimulate the personal resources of the actor, transform them into creators of a new sensorial dramaturgy and establish a new relationship with the spectators.

Roughly speaking, either you could go East or West. You could get inspiration from Asian theatres, anthropological ceremonies or religious rituals. Or you could begin with an intellectual analysis of the European tradition for the actor’s technique. The actor starts building the character out of given circumstances, with the support of psychology, the new science that was developed at the beginning of the last century. This new method was partially shaped by Stanislavsky. This new method was partially shaped by Stanislavsky, who was also aware of Meyerhold’s biomechanics, a method of engaging the intelligence of the whole body, starting from the organism and the unexplored possibilities of anatomy. When I speak of anatomy, I mean body-mind, because it is impossible to separate these two. We are impregnated by the autonomous and multiple activities of our brain. And we should not forget its archaic aspect, the reptilian brain, which separates us from the animals only by two percent.

I will speak about the demonstration I saw yesterday. Terzopoulos was able to discover the hidden resources of the actors, and for one hour and forty-five minutes we witnessed them drawing their personal expressive bow to the maximum, but in a very controlled way, just like a surgeon or an alpinist who carefully takes one step after the other. It was interesting listening to Terzopoulos’ actors speaking about their experience with him: how they were able to discover their source of energy, this flow of forces that they ignored and how they became capable of shaping them.

The Italian actor Paolo Musio asked “Where am I when I am here on the stage?” He was right, because the actors indeed are here on the stage and at the same time, they are somewhere else. Stefan Zweig gave the answer to the question where the actors are when they are playing, or where the authors are when they are writing or where the painter is when he puts one brush stroke after the other on the canvas. And Zweig also explained the reason why they are unable to speak about their creation on progress. Stefan Zweig says: “Because the actor is somewhere else”. The actor is literally in ecstasy and, let’s remember, ecstasy doesn’t mean to be lost somewhere, ecstasy means to be outside of your usual awareness, your daily familiar way of behaving. So, you are somewhere else, which means “there” in your own creative process, but also here, present on the stage in front of the spectators.

Another aspect of the actors’ demonstration indicates how Terzopoulos carried on the tradition of the beginning of the 1960s. The need and longing to reach the primary source was evident when starting a creative process. Sometimes this stimulus may seem simple, almost boring, sometimes it is a sudden illumination. But its energy becomes the umbilical cord which nourishes the actor’s relationship with the spectator.

The Colombian actor Juan Esteban Echeverry Arango described how, while working with Terzopoulos, he had gone back in time, discovering the archaic, the ancient, the animal side, which is fundamental in our profession.

Why are we attracted to dance? Why do we go to the opera, even though we don’t understand German, if it is Wagner, or Italian, if it is Verdi? Because dance and songs impact the non-conceptual parts of our brain and nervous system, they address to our animal legacy and heritage, to the intelligence of our total anatomy. And this is what today, in part, theatre has lost. Our contemporary “classic” is Samuel Beckett, an extraordinary writer who buries the actor and leaves only the head and mouth to speak. Undoubtedly, he is interesting. But when I am here, in Delphi, in the omphalos, in the centre of the cosmos, in this place where the ancient gods were speaking through the actors, then I feel how limited our craft has become. Our possibilities and our future lies within us, in our animal (dionysian) identity longing to find ways of communicating with the animal dimension of the spectators.

Greek culture managed to be rooted in this and was able to represent it in a unity of the two beings we are - half animal and half human. Some of them were intelligent, like the centaur Chiron, half horse and half man, the teacher of Achilles. Think of the Sirens, think of the Sphynx, think of the pure and innocent Minotaurus, jailed in the labyrinth.

In the name of my profession and my theatre colleagues I want to thank Terzopoulos because he is creating shelters, where we can meet, discuss and glimpse the hidden, secret part of our craft. I want to thank him for his artistic achievements, his strive for excellence, his enduring engagement. There is no living technique without responsibility, self-respect and discipline, and all these values we witnessed yesterday at the demonstration.

Therefore, I want Julia to end with a paean, a song to Theodoros, the mentor.

Theodoros – a Legacy with no Borders

VASSILIS PAPAVASSILIOU

Actor, Director, GREECE

I will speak as Kostikas about my friend Giorikas1. Theodoros is one hundred percent Pontic Greek while I am only fifty percent. So, “honor among Pontic Greeks”, as they say.

Theodoros is a second-generation refugee. He is Pontic but he is also Greek, so we could say that he is “hyper-pontios”2. He exists beyond and above the sea, literally speaking. He soars in the sky, he moves flying. In my opinion, the most distinctive characteristic of Theodoros Terzopoulos is the fact that he perfectly incarnates the Hellenic identity. As far as I am concerned, the only worthwhile definition of “Hellenic” is: “I am Greek, so nothing non-Greek is foreign to me”. Terzopoulos embodies this characteristic: he is Greek, so nothing non-Greek is foreign to him. Theodoros Terzopoulos trespasses the borders; he needs the borders in order to transcend them, not to be imprisoned by them and passively reproduce them.

This is also true of his artistic identity. The aesthetic equivalent of internalization is the transcendence and elimination of the distinctions between arts. And what better describes the work of Terzopoulos, which he systematically pursues in the last years, is a confession of faith to this emblematic principle of the reality of internalization. In my opinion, this iconic image is actualized in the installations. I have told Theodoros that I wish I wrote and spoke better to dedicate to him a proper piece about his latest works: “The talking installations of Theodoros Terzopoulos”. I am talking about the latest works of Theodoros at the Attis Theatre3. I believe that they perfectly reflect this dialogue, which takes the important form of existential identification, with that which is not typically theatrical – at least in the dramatic meaning of the word – but moves beyond, towards something else, which still seeks its name – if the name has any significance. This attitude, the theatre beyond drama, the theatre that recognizes the primacy of Dionysos – the Dionysos to whom Theodoros appeals is a confession of faith to a power that has nothing to do with the conventions and assumptions of the bourgeois drama – and this becomes clearer and more distinct as years go by.

Theodoros left Greece early: He opened the door and left. This is the reason he can exist. He knows well that modern Greece speaks with two voices. The first voice tells what is obvious: “Look how great I am! Stay here, live and enjoy!” This is the voice of the Siren. And the second one is the voice of Kassandra, who says: “Get up and get out of here! Pick up your things and leave!” Theodoros Terzopoulos knew that he had to “pick up his things” and leave in order to exist and of course experience at first hand the glory and recognition that historically follows the identity of the “re-imported Greek” in modern Greece. There is always a doubt about the accuracy of the criteria. For example, the residents of Thessaloniki doubt that they create something of importance unless they get the confirmation from Athens. The same applies to Athens on an international scale. They doubt that they create something of importance unless it is internationally acclaimed. Theodoros had this good fortune for which he has worked hard and, above all, believed in from the day he was born as a necessary condition of his life. And that is why today we can honor and thank him.

Thank you very much.

1Giorikas and Kostikas are two popular names among Pontic Greeks and also popular figures of Pontic jokes. Pontic Greeks are identified as those who originally come from the Euxinos Pontos at the Black sea.

2The word “hyper-pontios” in Greek means overseas. It is a composite word, formed by the words hyper and “pontos” which in ancient Greek means sea. The author creates a pun with reference both to Terzopoulos’ identity as a traveler (who crosses the seas) but also to his Pontic origin.

3The author refers to the performances Alarme (2010), Amor (2013), and Encore (2016).

Theodoros Terzopoulos at the Wilma Theater in Philadelphia

BLANKA ZIZKA

Artistic Director, The Wilma Theater, Philadelphia, USA

I first met Mr. Terzopoulos over the internet. Given our mutual reverence for the live experience, it is a rather ironic meet cute. I was working on the Polish play Our Class, by Tadueusz Slobodzianek, about the city of Jedwabne where in 1941 Polish Catholics, emboldened by the German racial politics, killed all the Jews. After the war, the Polish Communist government lied about it and the city even put up a small memorial suggesting that it was the Germans who killed the local Jews. The play looked at school children (hence the name Our Class), who were spending time together as kids, and later became each other’s executioners.

The play was intense, and difficult. The actors were on stage all the time and played their characters from six years old until their deaths. The play spanned over a long time period: 1925 – 2003. The actors portrayed characters who were either victims having to face death or survivors in hiding, scared and damaged for life; or the perpetrators who lied about these events for the rest of their lives.

I live in Philadelphia, the U.S., and my cast, comprised of white American actors, (and I purposely emphasize the word white because in the US white people and people of color have lived different histories) hadn’t experienced in their lives this kind of brutal disruption, and yet they had to create a theatrical reality on the stage that would be persuasive and evoke the complex realities and the tragedy of that historical moment in Jedwabne.

During one of the run-throughs of the piece, I just felt that actors were not with each other, not together. There was no energy and cohesiveness in the company. I was very much impressed with and influenced by the work of Jerzy Grotowski and Tadeusz Kantor when I lived in Czechoslovakia, and so I started Googling some of the workshops that were still happening in the Grotowski Institute. This is how I stumbled upon the workshop led by Theodoros and Savvas in Warsaw at TR Warszawa with Polish actors. He was talking to his actors about energy, focus, presence, the collective: all the elements I thought the performance of Our Class that night was lacking. I brought the video to the rehearsal and we watched it with my actors and discussed how these principles connected to our work. The performance was very different that night. The choreography hadn’t changed, but the performance went much deeper; actors were present and alert, listening to each other and creating the piece in the moment in front of the audience. I had in the meantime looked at all the video excerpts I could find of Attis performances and was hugely impressed by the actors’ physical, muscular presence. I don’t think I had seen anything like this since my time in Poland with the Grotowski theater.

Next, I flew to Athens to see the work and watch rehearsals. I caught a performance of Jocasta, watched many DVD’s of previous productions and even some of the early experimentations with endurance that had taken place in the early age of Attis before the current methodology was developed. I was impressed by the largeness and fullness of actors’ gestures, and by the unusual mixture of formality and vibrancy in actors’ performances. During the rehearsals session I was for the first time introduced to the idea of an infinite improvisation. After this experience, I decided to bring Mr. Terzopoulos to Philadelphia, we presented his Ajax, the Madness at the International Festival in Philadelphia. While in a performance, Mr. Terzopoulos offered his first workshop in Philadelphia to a group of approximately twenty actors. After the workshop we decided to go further and bring some of these actors back for another workshop. Finally we chose eight actors to perform in Mr. Terzopoulos’ Antigone, where the Philadelphia group of actors had a chance to perform alongside Attis actors. This group of actors has become the core company of The Wilma HotHouse that was established the same year as we produced Antigone in Philadelphia. We had an eight week rehearsal schedule for Antigone, the longest any of these actors had ever experienced, but it still was not an easy process, since the Philadelphia actors were both at the same time students of the method and creators of the performance and they performed together with Attis actors who had worked with Mr. Terzopoulos for many years. It had brought some anxiety into the rehearsal room. And I can say that some of Philadelphia actors really struggled with Terzopoulos’ principles. It was difficult for them to surrender their ego and sense of originality to the methodology and the work of the collective. I realized this was not just a physical difficulty, but a psychological one. In America, the rugged individual reigns. The idea that everyone must make a life for him or herself, relying only on him or herself, is embedded into every aspect of the American theater industry.