Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

'This is mental illness. It is unexpected strength and unusual luck and an uninterrupted string of steps. Then the next wave comes. And while you wipe grit from your eyes and swipe blood from your knees, the smiling faces in the distance call out: Why do you keep falling over?! Just stand up!' Conversations about mental health are increasing, but we still seldom hear what it's really like to suffer from mental illness. Enter Nancy Tucker, author of the acclaimed eating disorder memoir, The Time In Between. Based on her interviews with young women aged 16–25, That Was When People Started to Worry weaves together experiences of mental illness into moving narratives, humorous anecdotes, and guidance as to how we can all be more empathetic towards those who suffer. Tucker offers an authentic impression of seven common mental illnesses: depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, self-harm, disordered eating, PTSD and borderline personality disorder. Giving a voice to those who often find it hard to speak themselves, Tucker presents a unique window into the day-to-day trials of living with an unwell mind. She pushes readers to reflect on how we think, talk about and treat mental illness in young women.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 424

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

That Was When People Started to Worry

Windows into Unwell Minds

NANCY TUCKER

CONTENTS

Voice to the Voiceless

‘People say mental health isn’t discussed, and that’s why no one understands it properly. That’s bullshit though. I can’t go on Facebook without seeing ten or twenty posts about mental health. Maybe this is just me being blind and privileged, and I’m sorry if that’s the case, but I feel like mental health is discussed more and more these days. And yet still no one really understands. You cancel arrangements because you’re physically ill, and you’re unlucky. You cancel arrangements because you’re mentally ill, and you’re flaky. You’re “always bailing”. You take time off work for physical illness, and it’s unavoidable; you take time off work for mental illness, and you’re slacking. The posts about mental health that get shared on Facebook and retweeted on Twitter – a lot of them are great, but more of them are awful. They say nothing – nothing at all – and then at the end they say “STIGMA” or “RAISING AWARENESS” or “IF THIS JUST HELPS ONE PERSON”, as if those words were anything more than empty buzz-phrases. What’s wrong with contemporary representations of mental health? Well, for starters, they shouldn’t be called “representations of mental health”, because mental health is just the state of the inside of your head, the same way “diet” doesn’t actually mean “weight-loss plan”, it just means “what you eat”. If we’re talking about mental ill-health, we’re talking about mental illness. So what’s wrong with contemporary representations of mental illness? They’re sanitised. They’re superficial. They’re tokenistic. A lot of the time, they’re just inaccurate. I know I sound horrible saying this, and don’t get me wrong, it is really great that we’re working towards a better understanding of psychiatric as well as physical disorders, but … I don’t know. I just feel like … we’re not there yet. Yeah. To put it mildly, we’re not there yet.’

Laura, 23

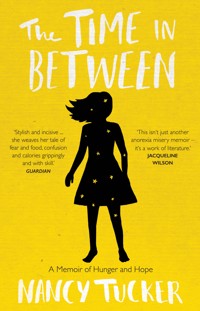

On the 31st of March 2015, I was flitting around a crowded bookshop like a scrawny, nervy star. There were stars on my dress and stars on my earrings and stars behind the lids of my eyes when I moved too quickly because I hadn’t eaten in three weeks. I was all sharp edges. There were stars on the cover of the book I had written about eating and not-eating and self-discovery and self-destruction. Tiny, hopeful, yellow stars. I’m flying, a tiny, hopeful, yellow voice tinkled in my ear. I’m flying, I’m flying, I’m flying.

On the 31st of July 2015, I was tethered to earth by a hollow tube, harnessing me to a tall, metal stand. Salty fluid chilled my arm and swilled the poison from my blood. My edges were gone, swallowed up by flesh I had thought I would never see again. Loose, hateful flesh, weighing me down like sand in a doorstop. All around were puzzled faces, furrowed brows: ‘You wrote a book? You have a job? You’re going to university? What’s wrong with you? Why do this?’ When I met their gaze, I felt the sharp points of a thousand shattered stars prickle behind the lids of my eyes, and I crossed and re-crossed my arms over the body I had tried so hard, and so repeatedly, to exterminate. I’m falling, a repetitive, unexterminated voice scratched in my ear. I’m falling, I’m falling, I’m falling.

On the 31st of December 2015, I felt as if I were buried deep underground, earth and rock and paving stones pressing down on my tired body. You can only fall so many times before you start to fracture. I was disintegrating into splinters of a soul, the raging voices thrumming in my ears a cacophony of blame and bile. Useless! Disgusting! Failure! When the nurses stitched up the patterns carved into my arms, they forgot to knit together the great, gaping wound in my chest. I walked out of the hospital, all fixed up, spilling dirt and desolation from the gash between my ribs. I’m broken, a dirty, desperate voice droned in my ear. I’m broken.

This is mental illness. It is vicious waves slamming you onto a rocky shore, and your tired body dragging itself up, and vicious waves slamming you back onto the rocks, and your tired body dragging itself up, over and over, until you think you might as well lie down on the sharp edges and let the water subsume you. It is smiling faces in the distance, bobbing above a picnic blanket, rolling their eyes and raising their hands: Why don’t you just stand up? Stand up – come and join us! It’s gorgeous over here! It is unexpected strength and unusual luck and an uninterrupted string of steps. Knee-deep, then ankle-deep, then the sun on your face and salt on your tongue. When the next wave comes – an unannounced, unkind fist – it knocks you forwards. You wipe grit from your eyes and swipe blood from your knees and cough mud from your lungs. In the distance there are smiling faces and raised hands: Why do you keep falling over?! Just stand up! It’s gorgeous over here!

At the beginning of 2016, I was marooned on the rocks. The previous year had seen me soaring, giddy on the high of self-confession and self-discovery and an ever-present undertone of self-destruction, until – running out of momentum mid-flight – I had come tumbling from the sky. Swathed in shame and bruised from the fall, I had walked into my university room three months after walking into a room on the psychiatric ward which had tried to stick me back together again, and I felt no more at home in the former than the latter.

‘What went wrong?’ people asked, six weeks into term, when I crumbled spectacularly and was bundled back home. ‘What was it you couldn’t cope with?’

I wanted to say: I couldn’t cope with being me. I couldn’t cope with finding myself in a brand new setting and being unable to turn myself into a brand new person. I couldn’t cope with the myriad hours I spent frantically, privately filling and emptying myself, or the blades I carried in my pencil case, or the search history crowded with questions about how many paracetamol tablets I would have to take to definitely die. I couldn’t cope with the drone in my head telling me: ‘You don’t deserve to be alive. You don’t deserve to be happy. You are a horrible, terrible person.’

I didn’t say that. I said there was a lot of pressure, and I struggled to keep up, and I felt homesick. And some people smiled and said: ‘Yes. You poor thing.’ And other people smiled and said: ‘But everyone feels like that when they leave home.’ And other people said: ‘Running away never helped anyone.’ And other people rolled their eyes and wrinkled their noses and thought: God. What a fuss.

I was terrified by what was happening in my mind – but I had already given my brain a book of its own. My insides had been scraped out and plastered onto the page, and my eyes needed to be swivelled outwards. So I rolled up my sleeves and prepared to sink my hands into the dark, gruesome innards of mental illness in the wider world. I wanted to climb into the grimiest corners of the unwell mind, and open the curtains keeping those corners trapped in gloom. I wanted to invite outsiders to peek through the grubby windows and see ‘what it’s really like’. I wanted to give voice to those whose internal demons rendered them dumb.

Over the following months, I contacted and met 70 young women – of all classes, colours and creeds – and heard stories of pain so visceral it knotted itself around my own nerves. We met in pubs and coffee shops, bedrooms and university houses, kitchens and living rooms. We talked about transformations from happy child to tortured teenager to hardened twenty-something. We talked about difficulties that had been waiting in the wings from birth, ready for a grand entrance. We talked about settled, ‘normal’ younger years, disintegrating to disarray in adulthood. These women allowed me to slip through tiny gaps in their armour, and stand shoulder to shoulder with the most bruised and battered parts of themselves, usually concealed from the melee of the outside world. The experience was harrowing, heartening and humbling.

Although the 100+ hours of interview I collected comprised the unique stories of unique women, their experiences clustered around certain core themes. A subset dwelled on difficulties with food; another on difficulties with mood. A handful relayed stories of alarming impulsivity; others of frightening compulsivity. While some described the agonies of post-traumatic stress, others painted pictures of psychotic duress. Although psychiatric diagnoses were not applicable in all cases – and, in any case, such diagnoses tend to mingle with one another like ambitious millennials at a networking event – most women’s experiences fell within the bounds of one ‘label’ or another. And so, I created characters embodying each of the major difficulties my interviewees described: depression (Abby); generalised anxiety disorder (Freya); borderline personality disorder (Maya); self-harm (Georgia); disordered eating (Beth); post-traumatic stress disorder (Holly) and bipolar disorder (Yasmine). These characters are not real people: they are composites of real people. To have transposed individual interviews directly onto the page would have been unethical (and the resultant product would not have been a book). However, every significant experience my characters undergo, every significant belief they hold, every significant conversation they have is a real event, recounted by a real person. Each character’s ‘story’ is a potted memoir of lives; it is not a potted memoir of a life.

Why women? Put simply, women are more vulnerable than men to many common mental health conditions. The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS), which has been conducted every seven years since 1993, offers some of the most reliable data for the trends and prevalence of mental illnesses. The most recent APMS (2014) found that all types of common mental health problems, including depression and generalised anxiety disorder, were more prevalent in women than in men. The discrepancy was most marked among young people: 26 per cent of women aged 16–24 reported symptoms of a common mental health problem, compared to just 9.1 per cent of men of the same age.1 This survey sampled people from England only, but similar gender patterns have been found in Wales,2 Northern Ireland3 and Scotland.4 Young women also report higher levels of self-harm and suicidal thoughts than any other group.5

This is not to say that male mental health is not important and worthy of exploration. In 2014, the Office for National Statistics reported 6,122 suicides in the UK, of which 75.6 per cent were male.6 Given that suicide and suicide attempts are associated with a psychiatric disorder in 90 per cent of cases,7 men are clearly suffering. Further, young adult males experience greater personal stigma surrounding mental health problems than their female counterparts,8 resulting in a possible reporting bias: men may resist admitting to a mental health problem, hence statistics concerning this population may be inaccurate. This is before considering the mental health of transgender people, or those with a complex gender identity, who may face elevated levels of both psychological distress and stigma.9 A book exploring mental illness within these populations would be highly relevant – but I would not be the person to write it.

Why young people? A 2005 prevalence study carried out in the USA predicted that 75 per cent of mental health problems are established by the age of 24.10 Therefore, it must be of paramount importance to learn more about the wellness or illness that develops during this early chapter of life.

To me, these seemed objectively sound reasons for choosing to focus on this specific population, but it would be naïve not to acknowledge that personal interest played a part. In my experience, being a young woman is, at best, challenging and, at worst, agonising – and I was interested to learn whether or not this sentiment would be echoed by others of my age and gender who suffer from mental health problems.

Before I began interviewing, my primary concern was whether the conversations would constitute a basis for engaging writing. I knew I would find these young women’s stories interesting, but I did not know whether they would translate into readable material. As readers, we tend to look for stories that are wide and full and exciting – but mental illness is often small and empty and dull. By the time I had finished interviewing, my primary concern had morphed: my interviewees’ experiences were too vivid; too shocking; too dramatic. I was convinced no one would believe that these things had really happened. There is little I can do to challenge this state of disbelief, except to reiterate: it is all true. It is all real. These things happened. These things happen.

I am aware that there may – still – be those who look upon these stories as a collective indulgence of ‘first-world problems’. Although the women involved in this project by no means represent a single social class, none came from abject poverty or deprivation. They had roofs over their heads and enough food to eat. Most were educated, employed and in good physical health: they had at least some degree of ‘privilege’.

However, I see no value in comparing the pain entailed by mental illness with the pain entailed by, say, those involved in warfare, national disaster or persecution. To do so suggests that there is some universal ranking of suffering, which puts one type of distress above another. It is ludicrous to compare forms of pain, expecting to discern a ‘worse’ and a ‘better’. It is also absurd to suggest that privilege should preclude or invalidate unhappiness: one’s crushing depression, all-consuming suicidality or paralysing anxiety cannot be discounted because one is white, heterosexual or middle class.

Where is the value in comparing their struggles? We move through the world within the bounds of our own experience, which has peaks – the most intense happiness we know – and troughs – the most intense misery we know. The scope of this experience varies widely: one person’s lows may be another’s middle ground, and the distance separating the depths from the apex can be vast or small. The location of the low is less important than its position within the ‘experience space’: being at the depths of said space, for anyone, feels wretched. For this reason, comparing two people’s nadirs – Things aren’t really that bad for you; just think what others go through! – is unhelpful. I have treated all stories as equally valid, because they are equally valid.

Recently, I was berated for referring to those experiencing mental illness as ‘sufferers’. ‘You can’t say that,’ the person said. ‘It’s judgmental. It’s politically incorrect.’ They were mentally well, but had assumed offence on behalf of the affected party. Who has decided that the suffering entailed by mental illness must be hidden? In my experience, it’s not the mentally ill themselves. My interviewees were united on this front: their illness caused them to suffer. They were sufferers. To say, ‘a person living with a mental illness’ implies harmonious co-existence between the disorder and its host – and this is inaccurate and ignorant. Societal rejection of the word ‘sufferer’ is indicative of a much larger problem: unwillingness to accept the true scale of the duress involved in a mental health condition. Yes, byallmeans, have a mental health problem, but, for goodness’ sake, don’t suffer from it. What’s the point in having it unless it’s going to enhance you? I only want to hear that your depression has made you grateful for sunny days, that your anxiety has made you sensitive to others’ feelings, and that your eating disorder has made you glad to be alive. I don’t want to hear about the unpleasant bits. I don’t want to hear about suffering. In this book, I refer to sufferers as sufferers, not out of disrespect, but in recognition of torment they face.

My aim has always been to present stories honestly. For this reason, the book contains passages some might find upsetting – particularly those with personal experience of mental illness. I have provided a broad overview of the conditions described in each chapter in the table of contents, but it is inaccurate to suggest that symptoms restrict themselves to a single disorder so neatly. Discussion of self-harm, for example, occurs in Georgia, but also Yasmine and Maya. Disordered eating is the core pathology in Beth, but there are references to weight and body image in Abby, Holly and Maya. In Holly, there are descriptions of sexual assault, but sex and relationships also feature in Yasmine and Abby’s stories. These descriptions are – I hope – never gratuitous, but nor are they deliberately moderated. I have simply recounted thoughts, feeling and incidents as they were recounted to me. If you are concerned about the impact of such material on your own mental health, I urge you to think carefully before continuing. There is no pressure or urgency. Books will always be there; your vulnerability may not. A further content notice: the stories and reflections that make up the bulk of the narrative are book-ended by ‘guides’. As I hope is evident, these are not intended as literal instructions on how to develop or recover from mental illness, far less a representation of my own opinions. Rather, they serve to highlight the common misconceptions my interviewees felt surrounded their conditions. At times, they are humorous; at times, they are harsh, callous and inappropriate. This is because those experiencing mental illness are all too often treated harshly, callously and inappropriately.

The women who make up the characters captured between the following pages did a brave and remarkable thing in contributing to this book. They set aside their impressive outer shells, and in so doing uncovered something more affecting than any competent, capable façade. The selves these women revealed were flawed, messy, achingly vulnerable and deeply real. It is this mess of flawed, vulnerable reality that I am honoured to share.

Abby

7.33. I have been awake for three minutes, and have had enough of today.

7.36. I have been awake for six minutes, and have had more than enough of today.

7.39. I will get up in one minute.

7.41. I have missed the opportunity to get up in the 40-minute slot. I will get up at 7.50.

7.53. It really makes no sense to get up before 8.00 now.

8.03. I have left it too late. If I get up now, I will be rushed. When I swing my legs over the side of the bed, the tension will spread upwards, through the soles of my feet, into my calf muscles, around my pelvis, up to my chest. It will be tight and squeezing and sore. It will be like stepping into a bodysuit of tension, and I won’t have time to shower, and not showering will make me more tense, and I will scuttle around the room like a crab, ferreting clothes from the piles crouching in the corners. They will smell stale and sour and will be too creased to wear without ironing.

8.09. There is no way I have enough time to get out the iron, let alone the ironing board.

8.11. I can’t iron this morning, so I have nothing to wear, so I can’t get up.

8.16. If I get up now, I will be really rushed. Maybe I still have a fresh shirt hanging in the wardrobe, and if I wore trousers the creases might not show as much as they would in a skirt …? But then I would have to brush my hair, and it’s been four days since I washed it now. The spines of the brush would leave oily indentations between the strands. What if I pulled it into a ponytail without brushing? Could that work? No, of course it couldn’t, don’t be ridiculous, don’t be absolutely fucking ridiculous, Abby.

8.22. I have to leave the house in eight minutes. I have to leave the house in eight minutes in order to arrive on time. I have to leave the house in thirteen minutes in order to arrive late-but-not-so-late-it’s-an-issue-late, and eighteen minutes in order arrive pretty-fucking-late-but-maybe-possibly-hopefully-only-late-enough-to-warrant-a-raised-eyebrow-and-not-a-‘Can-I-have-a-word?’-late. But calculating that has taken two minutes. So now I have to leave the house in six minutes or eleven minutes or sixteen minutes, and—

8.25. I can’t breathe. I can’t fucking breathe. There is a corset laced up around me, but it is laced up too tight, crunching my ribs together like a rattle of xylophone keys and grasping upwards, upwards, upwards, clenching around my chest, clasping around my throat, squeezing so fiercely that all the air inside me is forced out …

8.27. I can’t get there on time. I can’t be late. But I can’t get there on time. But I can’t be late. And I can’t … I can’t … I can’t I can’t I can’t I CAN’T I CAN’T I CAN’T I—

8.29. There are billions of burning, blistering beetles crawling up the back of my neck, over the top of my scalp. My skin is melting, sizzling and splitting under their feet. My head is on fire, and my tongue has swollen, thick and slimy, and my heart is banging the blood away from my limbs, away from my lungs and into my eyes, my ears, my mouth, until all I can see and hear and taste is the hot, thick slime of my tongue …

8.30. Silence. Stillness. Soft and sad as a soggy cornflake, softening sadly in chalk-white milk dregs.

8.31.

I can’t get to work on time now. Even if I rocket up, stuff un-socked feet into uncomfortable shoes and leave the house trailing an armful of clothes, ready to button myself into ‘competent professional’ mode on the train, I won’t make it. If I leave for work now, I will be late. I can’t be late. My manager has already had to ‘have words’ about my lateness, and the words that she has had have left me fairly sure that they are not the sort of words she enjoys having, and that if she has to have many more of them she will make sure the need for those words to be had is eliminated. If I am late, I will be eliminated. I can’t be late, but I can’t go to work without being late, so the solution is clear: I can’t go to work at all. Simple. Why didn’t I think of this in the first place?

I am still lying, mummy-like, but the knots of panic trussing my insides begin to unravel. Like rainwater dripping from leaves, the tension gradually drip-drip-drips from my body. There is a dull ache across my shoulders and a throbbing ache at the back of my head and a gnawing ache between my ribs. I ache all over, as if I have just emerged from a boxing match with an opponent who has run rings around me. But my challenger was not a brawny sportsman – it was a dense mass of myelin. A three-pound lump of fatty grey matter that trounces me every time.

When I sit up, the weight of the duvet falls away, goosebumps erupting across my arms. Harry’s side of the bed is a shell of early-morning clumsiness and boy-smell – crumpled pillows and rucked-up sheets infused with testosterone and stubble. Harry sets his alarm for 6.00 in the morning. Harry is up by 6.15. Harry drinks a sludgy concoction of bananas and soy milk and whey protein on the way to the gym at 6.30. Harry does legs on Mondays and arms on Tuesdays and something else and something else and something else on Wednesday– Thursday–Fridays and showers in the nice clean gym showers at 7.30 and is at work by 8.00, and I don’t because I’m not Harry and I won’t ever be Harry, and sooner or later I won’t even have Harry any more because I get tethered to my bed in the mornings by crumpled clothes and greasy hair. And, anyway, I never consume any whey. Harry smells of safety and relief. I will never smell like Harry.

I creep across the hallway, desperate to lock myself in the bathroom and scrub my skin raw. Porridgy breakfast-time chatter skitters up the stairs. When you squeeze six people into a five-person house, what happens? It’ll be fine! we said, waving away raised eyebrows. It’ll be cosy! we said, mouths distorting in exaggerated grins. It’ll be such a laugh! we said, doubling over, grotesque caricatures of mirth. What actually happens is that there’s noise, noise, noise everywhere, and the air is thickened by the smell of six different deodorants and six different dinners cooking, and the low, ominous hum of the washing machine is a constant, and there is never, ever an hour or minute or corner of a room that is yours and yours alone. It is definitely cosy, but rarely fine. And I very rarely laugh.

The trickle from the shower nozzle spills lazily over my too-big body in the too-small stall. It is not quite hot enough to stop me shivering. I am working Tropical Paradise-scented shower gel into the hair under my arms when there are two sharp taps on the bathroom door. They sound clipped and accusatory. I feel sticky and hairy and indecently fleshy, and I wish I didn’t smell so strongly of Tropical Paradise.

‘Abby? Is that you?’ Ellie-from-across-the-corridor doesn’t speak: she chirrups. It is unmistakeable and inescapable. Her voice sounds like her face: round and smooth and perpetually hopeful. When I open the door, cold air prods at the nakedness under my towel. Ellie has been standing right up against the wood, listening, and for a moment we are almost nose to nose. As she stumbles back, her brown eyes come into focus, the smooth skin between her plucked brows puckering.

‘Oh, hey? Yeah, so I’ve got a seminar starting at 9.30? On campus?’ Her persistent upwards inflection questionises every sentence. It is infuriating. ‘I was just wondering if I could just …?’ She gestures vaguely behind me to where her toothbrush and toothpaste balance on the edge of the sink. Even her movements feel like questions. Stop asking me things, Ellie, I think as I lumber past her, like a great, apologetic hippo. Can’t you see I have no answers?

Back in the bedroom I feel sticky as I pack myself into yesterday’s clothes. I didn’t rinse myself properly. The soap still coating my skin makes me stiff. I sit heavily on the bed, knees hunched up to my chest, and the day stretches ahead of me like a deserted racetrack. An ocean of unfilled time, to float in and swim in and wallow in. Surely there could be no greater luxury than a sea of blank time. What freedom. Only my unfilled day doesn’t feel tantalising. It feels like a sentence. I can’t look at my phone because I don’t want to see the whingeing red dot above the voicemail icon and I don’t want to listen to the whingeing grey voice of my manager. She will not be able to mask her exasperation at having to ask why, yet again, I have not seen fit to grace the office with my presence. I can’t open the curtains, because I think it’s sunny this morning. There is waxy yellow light bleeding through the un-curtained corners of the window, and it makes my ears ring and my throat feel thick and sore. When it is sunny you should be warm and colourful and Shall we eat lunch outside today? Why the hell not?! We’re young and free and beautiful! What’s not to celebrate?! You shouldn’t be soapy and scratchy and indefinably sick.

I screw my wet towel into a ball and drop it by the bed. The laundry basket is three feet away, but those three feet look complicated today. The towel can sit in a grouchy ball until it starts to fur and reek. I fish a fat bottle of rattly tablets from the silt of my bedside table and twist off the childproof cap. One pink sleeping pill of dubious provenance purchased from eBay will have no effect on me. Three pink sleeping pills of dubious provenance purchased from eBay will make me drowsy. Five will knock me out. Six will leave me with a hangover. I count the pills in my hand – 1-2-3-4-5-6-7 – and swallow them with flat Coke that tastes of sugary dust. Then I pull the duvet up, over my head, and the world goes black until Harry shakes me awake in the evening.

When Harry shakes me awake in the evening, we don’t talk about my greasy hair or my mouldy towel or my work shoes, lying exactly where they lay when he left this morning. He doesn’t mention the seven texts he sent me over the course of the day and the seven replies he didn’t receive. He doesn’t ask why these days – the empty days – are starting to outnumber the not-empty days, and we don’t acknowledge the fear that thickens the silence between us. Harry goes downstairs. I hear him laughing in the kitchen with the others, and I wish everyone in this house would stop bloody laughing all the time, as if they only laugh to highlight my not-laughing. He comes back upstairs later – quite a lot later – with two bowls of pasta and green pesto. The food feels pappy in my mouth. While we eat, Harry watches football highlights on his phone with his headphones in.

As the day ebbs away, replaced by a blue-black bruise of night, Harry showers and changes, and I put on last night’s pyjamas and question why I took them off in the first place. We lie, limbs tangled with the covers, wishing for a breeze to buffet the curtains. We lie for a long time, not sleeping, not speaking. Eventually I shift towards him, and he loops an arm around me, and I rest my head on the ball of his shoulder. His breathing is very deep, and every breath sounds like a sigh, and there is a throbbing pain in my nose and throat as two tears slide down and wet his white T-shirt. There is nothing I can say that I have not said before, and the despair in the room is as close as the heat. We are too hot like this, wrapped in one another, but we do not move. Sweat gathers in the creases of my neck, and I want to lift my hair, but I do not move. Harry falls asleep, and his arm falls away from my back, but I do not move.

When I met Harry I was drunk and nauseated and normal. We caught spangled glimpses of one another in the strobe lighting of a horrible club, and mashed our bodies together to the beat of horrible music, and he stood and flapped his hands as I was horribly sick in the gutter outside. When I had finished spewing dark swirls of vodka and Coke onto the paving stones, I wiped my mouth with the back of my hand, straightened up, and cocked my head to the club’s hungry music. ‘We going back in then or what?’ He looked at me, beer and confusion clouding his watery eyes, and said, ‘What? Back in there? There’s no way we’ll get back in. You’re so drunk.’ And I tried to walk too fast on ridiculous heels and wobbled precariously and slurred, ‘Try and stop me.’ He hoisted me up and looked at me like I was the best thing in the world and said, ‘You’re fucking mental. You know that, right?’

The first university year was a whirlwind of books and bravado and Harry. We were charged particles, barrelling towards each other over and over again, never sure whether we would collide in an embrace or a blistering of bitter words. We fought and we pined and we didn’t speak for weeks, and then we made up, faces fused by saliva and contrition, insatiable for whatever young, giddy derivative of love we had. We were electrons.

The weeks ran through my fingers like water. Second year swung up like a garden rake in a slapstick sketch, and I stumbled through the first term reeling from the thwack between my eyes. The safe, sensible schedule of day and night that had contained my life up to that point fell away, and I vacillated between weed-smoking, wine-glugging oblivion and keyboard-tapping, coffee-downing anxiety. I returned from raucous nights out in the early hours of the morning and collapsed, broken, into bed, then woke mid-afternoon and feverishly tried to catch up on weeks’ worth of essays, watching the sun rise without leaving my desk to wash, change or even remove the smeared nightclub make-up.

I dealt with self-doubt and self-loathing through hair dye and piercings. ‘Crisis piercings’, I called them. When I kissed Harry goodbye one morning, my past-the-shoulder brown hair tickled his cheek, and he tucked a strand behind my single-pierced ears. Later, I lay with my head in his lap and he ran gentle fingers through bleached tufts, reassuring me over and over that he did like it, he really did think it looked good; it was just a bit of a surprise, that was all. He traced the loops of the five gold rings in each of my ears. His palms were sweaty and smelled of salt. When I cried he asked me why I’d done it, and I said I’d just needed a change. He smiled at me like I was the best thing in the world, but this time it was like he was realising that all the best things in the world are warped and strange at the edges. And he murmured, ‘You’re fucking mental. You know that, right?’

By the time I moved into the third-year house I was spiralling. Within weeks, the nauseating knot of dread once reserved for essay deadlines had set up permanent residence in the bottom of my gut, and I was dogged by a relentless sense of doom. Desperate, I made an appointment with the university counselling service, but as Therapy Day drew nearer I felt more and more incapacitated by fear. The fear was as intangible and illogical as it was intense. The clock ticked closer and closer to Therapy Time, and my body curled tighter and tighter into an embryonic ball, and I thought: I cannot go. I cannot go. I did not go. When Harry came home from his afternoon lecture, eager to hear how the session had gone, I collapsed on him in a slump of snot and anguish.

‘You didn’t go? What do you mean you didn’t go?’ he moaned, raking a clawed hand through his hair.

‘I couldn’t! I couldn’t!’ I howled, bunching myself into a knot. ‘I was too anxious!’

The air filled with my sniffles and Harry’s sighs and the ringing of obvious, unspoken words. Too anxious to get help with my anxiety? The tide in Harry’s eyes ebbed weakly.

Spring term and six weeks of blank time leading up to a coursework deadline. For a month I deteriorated steadily, barely noticing the sheer drop on the horizon until I was tumbling down, down, down. I became almost entirely nocturnal during the final two pre-deadline weeks, snatching an hour of sleep at midday here, another two hours at 5am there, otherwise sitting so still at my desk I imagined myself putting down roots between the floorboards. When I did leave the house, it was to wander aimlessly through the streets – in the middle of the night just as easily as the day – my mind blank, senses dulled. I forgot how it felt to have a chest that didn’t lurch and convulse with every breath, and a head that didn’t buzz with low, insistent pain, and muscles that didn’t tic and tense of their own accord. After thirteen days and 23 hours I had reached the end of the assignment and my tether. My tutor would be collecting hard copies of the coursework from his desk at 7am; the printer spat out my final page at 6.30.

‘You’re not going to get there if you walk,’ said my housemate Chris, leaning against the kitchen doorframe, watching me struggle to tie shoelaces with uncooperative fingers.

‘Oh. Well. I might,’ I said, knowing that I wouldn’t.

‘No, you won’t,’ said Chris, knowing that I wouldn’t.

‘No. I suppose I won’t,’ I sighed, accepting that I wouldn’t. I couldn’t summon the strength to care.

‘Take my bike,’ said Chris, bundling me out of the door, and, in a daze, I did. The early morning air was crisp and refreshing, and I felt as though I’d been put through a laundry mangle in the night. My legs ached with the effort of propelling the bicycle wheels round, and my throat stung with the unfamiliar influx of oxygen, and suddenly one of my feet went cold, and then the other, and I heard something bump onto the ground; I looked down and saw that my shoes had fallen off and were lying in the road behind me, as if running a marathon independent of an athlete. My feet were bare on the bicycle pedals and the wind was whipping between my toes and I felt horribly, ridiculously naked, but it was 6.45 and I was ten minutes from where I needed to be and I had to keep forcing the bicycle wheels in jeering, spiteful revolutions.

When I got back to the house, Chris and Harry were sitting at the table, eating toast topped with sand-coloured peanut butter, drinking sand-coloured tea from mismatched mugs.

‘Did you get it in?’ Chris asked, teeth doughy.

‘Four minutes to spare,’ I panted. Chris whooped, then choked, and raised his mug in an elaborate gesture of triumph. Harry didn’t. Harry looked at me.

‘Where are your shoes?’

‘Fell off. On the way. Couldn’t stop. No time.’

Harry looked at me for a long, swollen moment. I was wearing a scrubby black coat over plaid pyjamas, feet mottled purple by the cold of the morning. Salt crusted from my nose to my mouth, and I tasted iron on cracked lips. I was shivering from head to toe, and my breath came in short, sharp gasps, and the blue-black bags under my eyes were so heavy I could feel them dragging down my lids.

Harry looked at me. He didn’t look at me like I was the best thing in the world. He looked at me like I was a monster, or a deformed baby.

‘You’re fucking mental,’ he whispered. The tears trapped in his throat made his voice as thick and gluey as the peanut butter collected at the corners of his mouth.

‘You’re fucking mental. You know that, right?’

If you had to draw a picture of a counsellor, you would draw Anna. If you had to cast a film featuring a counsellor, you would scour the country for an actress who looked exactly like Anna. If you were a woman who looked like Anna, it would be criminal to pursue a career in anything but counselling. Everything about Anna is soft and neutral and unthreatening. She is a remarkable feat of unremarkability. Middle-aged, middle-height, middle-build, dressed in thoroughly middle-of-the-road clothes and sitting in an office on the middle floor of a building in the middle of the street.

‘Perhaps you’d like to tell me a little about what’s brought you here today, Abigail?’ Anna asks, in a middly sort of voice.

And I think: Yep. I can do this one. I know the answer to this one. No revision, no panicked trips to the library – I’ve got this one down.

‘Yes. Well. I suppose I … The thing is, I …’

And then I think: Fuck – I can’t do this one. Fuck. This is supposed to be the easy one. This is like the starter for ten, except much easier. Like the starter for five, or the starter for two, or … If I can’t manage this one, how the fuck am I going to manage the rest of them? The really deep, probing ones? Fuck. Why am I here? I don’t really have ‘problems’. I mean, of course I have problems, because everyone does, but I only have problems, not Problems. I only have problems like, ‘Oh no, I haven’t done any washing in six weeks and have no clean underwear.’ Like, ‘Oh God, I really drank too much last night and now I feel like my tongue is made of carpet and my insides are made of mud.’ Like, ‘Oh fuck, I’m at work and I’m crying, and everyone can see me crying, and I don’t know why I’m crying but I know I can’t stop crying.’ Normal problems.

In the waiting room, I saw a lot of people with real, serious Problem problems. The girl whose face was so red and puffy she looked like she was in anaphylactic shock. The boy whose heel tapped incessantly against his chair and whose fingers drummed out an anxious rhythm on his thigh. The girl whose legs were the width of my wrists, who bobbed from foot to foot in front of the notice boards like a lissom rubber duck, pretending to read the pinned-up leaflets about sexual health. They deserve to be here. I don’t. I’m a fraud.

I am crying. Not civilised, blotting-a-tear-delicately-from-the-cheek crying. Sobbing. Howling. I am sitting opposite the queen of non-description in a chair and a room and a building designed to be nondescript, but I am not being nondescript. I can think of few times when I have been more demonstratively descript.

‘What about that question makes you so upset, Abigail?’

Oh, Anna. I don’t know. I’m upset because there’s too much to say, and I’m scared of saying it to you, because – bless you, Anna – I’m sure you’re doing this job because you want to be kind and solve people’s problems, and good on you for wanting to help, but the thing is, Anna, I feel like, with me, it’s just not going to be that simple. Because with me, you see, Anna, I am the problem. I’m upset, Anna, because even though I don’t know you, and I’m not supposed to care what you think, and you’ve clearly put a lot of effort into convincing me that you’re a completely blank canvas, I really want you to like me, Anna. And I’m upset because, if I tell you what’s brought me here, the fact is, Anna, you’re not going to like me. If I tell you about the not-getting-out-of-bed-in-the-morning and the cancelling-plans-at-the-last-minute and the sleeping-through-the-day and the worrying-through-the-night and the being-horrible-to-poor-Harry, you’re not going to like me, Anna. No one does, and no one should. Anna, I think I’m upset because I know it’s all my fault. Everything. All of it. It’s all my fault, Anna.

I don’t launch this torrent of words at Anna. I tell her about the overcrowded, over-noisy house and how cosy and how fine and how much of a laugh it was supposed to be, and how actually it’s just a messy prison where I can’t relax. I tell her about sweet, kind, patient Harry and how much better he deserves, and how I’ve started to wonder whether he might prefer to come home and find me dead than come home and find me asleep in bed. I talk and cry and shred tissues for 50 minutes, and when I go back to real life I feel as if I’ve been sitting in Anna’s room for 50 years.

The doctor Anna sends me to see is hassled and has letters and prescription pads and half-drunk mugs of coffee all over his desk, and after alarmingly few words and an alarmingly brief questionnaire I find myself walking across the road to fill a prescription for antidepressants. The pills, shaped like tiny white bullets, are shame and comfort – proof that I am cracked and broken; hope that the cracks and breaks are fixable. For the first few days, gulping down a tablet every morning has little effect. After swallowing I sit, tense, on the bed.

Is it working yet? Maybe now? Or maybe now? Do I feel as bad now as I did yesterday morning, when I hadn’t taken a pill? If I do, is that definitely because of the pill, or could it just be that I slept better/it’s a warm day/it’s a Thursday? Do I feel better yet? Maybe now? Has it started working yet? How about now? Now?

When it finally kicks in, the medication gives me the boost of a strong cup of coffee. I don’t feel happier – not in a sunny, laughing-and-smiling way – but the murky sense of dread that has been underscoring my day-to-day life begins to peel away, until one day I realise it has been replaced with a liberating indifference. For the first time in years, I am not foggy: I am focused. Getting up with my alarm no longer feels like a mountain to scale – more a hummock to hop over. I can go to work and get things done and come home in the evenings and go to the pub and not care about the noisy house or the imperfect achievements or the gnawing pointlessness of it all. I can function, and functioning feels fantastic after aeons of fog.

At first, Harry is elated by the departure of the haunted spirit that has been using his girlfriend as host. Who cares if my sudden energy is bordering on mania? At least I’m not a lifeless slug any more! So what if I’m drinking a bottle of wine a night, clinging to the acidic habit like a limpet? At least I’m having a good time! Does it matter that my newfound functionality is becoming more dysfunctional with every passing day? At least it’s different! Within weeks, the tide in his eyes has changed. His teeth gnaw at his lips. His eyes track the wine from bottle to glass to my lips. We are together – stoically, immovably together – but it is a taught, sour thing, crackling with negative energy. We are electrons.

One particularly messy morning after a particularly heavy night before – drinks and clubs and pumping music and little white pills under my tongue with no prescription – I open my eyes to a splintering headache and Harry’s broad, T-shirted back, arched over as he runs his hands through his hair. I reach across the gulf between us, pressing the flat of my hand to his warm body, and for a moment I feel him flinch.

‘How are you feeling?’ he mutters, turning to face me.

‘Like sick,’ I yawn, forcing a smile that feels like a leer.

‘Look. Don’t you think … I mean, I don’t know, Abs. I know I’m not inside your head. And I know it’s not, like, easy, or whatever. But don’t you think maybe these meds might be a bit … Are you sure they’re a good idea?’

Indignation heats my cheeks. ‘What? What are you saying? I don’t know what you mean. I don’t – I can’t – Harry, what?’

‘Come on, Abs. You do know. You have to know. You’re out of control. It’s not working.’

‘What’s not working? The meds? My meds aren’t working for you? Sorry, Harry. I totally forgot that you were the one with depression. You’re the one who didn’t used to be able to get out of bed in the mornings and who couldn’t leave the house for days, aren’t you?’

‘Abs, you know I’m not—’

‘Actually, Harry, these are my meds. They’re my meds because they’re my feelings, and I think it’s going great. I love these meds. They make everything better for me. Look at me: I can go to work now, and I can go see my friends now, and I can go out and have a good time now, and I—’

‘YOU’RE SO FUCKING SELFISH, ABBY!’

I have been so caught up in my righteous tirade of reasons why Harry is wrong and I am right that I haven’t noticed his muscles go tense and his jaw set hard and the tic at the corner of his eye start to dance. It takes me by surprise that there is suddenly a roaring volcano of a man standing over me, spitting resentful lava.

‘You’re the most selfish person I have ever met! Do you realise that? All you ever talk about is yourself! All you care about is your life and your problems and the things that make stuff easy for you! But you’re not the only one in the world, Abby! There are six of us in this house, and there are two of us in this relationship, and only one of us has become a fucking nightmare over the past few weeks!’

‘But I—’

‘No! You don’t get to say that any more. You don’t get to say anything any more. You don’t get to. You don’t get to …’

His voice makes a sound as if it has been snagged by a fishing hook, and his face sags like a punctured bouncy castle, and he is jelly on the bed. He is sobbing, and I am sobbing, and we are holding onto one another like babies clutching fingers. We cry and cling for minutes, snot and sweat mingling on our skin, and I feel like the emperor, exposed by a child. My selfishness has shrouded me, protected my modesty, but now it lies wrinkled at my ankles.

‘I want you to be happy, Abs.’ Harry chokes, muffled by the swell of my chest. ‘But I don’t want you to be like this. I’m scared.’

I run my fingers through his thick, dishwater-blonde hair, and think maybe I am selfish, because maybe we’re all selfish, deep down.

Harry feels young in my arms. He shudders with each breath. I feel heavy and tired and nothing more.

As it struggles to force its way through the leaves of the trees in next-door’s garden, the sun casts patchwork shadows onto my legs. I am eating handfuls of dried cherries from a brown paper bag. They are sour. They stick my teeth together. On the narrow aisle of scrubby grass stretching out in front, Chris and Harry flick a dented football lazily back and forth. They are like lanky children, allowed out to play before bed.

I pour myself a second half-glass of red wine. It tastes soft and deep in my mouth. I won’t drink any more after this. It’s been a few months now, and the insatiable hunger for sensation that growled in the wake of the last medication hasn’t returned. The new pills make me feel clear-headed and capable. There is no chaos around the corners.

Harry glances at me over Chris’ shoulder, raising his eyebrows in a silent question. Harry still has anxious eyes. Beetle eyes. They skitter across my face. It is hard for him to accept my smile when he is the one to grip my hand and guide my breath at two in the morning, insisting over and over that I’m not going to die, that my heart isn’t going to beat out of my chest, that I can breathe, that the world won’t collapse in a heap of bones and rubble. But he is learning – we are learning – not to panic about the black days, or the dark thoughts, or the panic attacks. At my last session with Anna, I told her that Harry and I were going to stay together after all. That maybe it wouldn’t be forever, but it would be for now. And she wasn’t allowed to tell me what she thought, because that wouldn’t be middly at all, and it was probably just refracted light ricocheting from window to iris, but I felt like her eyes twinkled approval.