Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

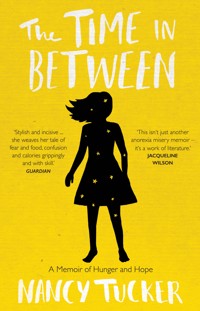

When Nancy Tucker was eight years old, her class had to write about what they wanted in life. She thought, and thought, and then, though she didn't know why, she wrote: 'I want to be thin.' Over the next twelve years, she developed anorexia nervosa, was hospitalised, and finally swung the other way towards bulimia nervosa. She left school, rejoined school; went in and out of therapy; ebbed in and out of life. From the bleak reality of a body breaking down to the electric mental highs of starvation, hers has been a life held in thrall by food. Told with remarkable insight, dark humour and acute intelligence, The Time in Between is a profound, important window into the workings of an unquiet mind – a Wasted for the 21st century.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 492

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The TIME IN BETWEEN

A Memoir of Hunger and Hope

NANCY TUCKER

Published in the UK in 2015 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by

Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India,

7th Floor, Infinity Tower – C, DLF Cyber City,

Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

Distributed in Canada by Publishers Group Canada,

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300

Toronto, Ontario M6J 2S1

Distributed to the trade in the USA

by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution,

The Keg House, 34 Thirteenth Avenue NE, Suite 101,

Minneapolis, MN 55413-1007

ISBN: 978-184831-830-4

Text copyright © 2015 Nancy Tucker

The author has asserted her moral rights

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in New Caledonia by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK

by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

About the author

Nancy Tucker is a 21-year-old writer and nanny. She suffered from both anorexia and bulimia nervosa throughout her teens, but is now on the road to recovery and has gained a place at Oxford to study Experimental Psychology in 2015. She lives in London.

For my very special grandparents, John and Deirdre. I don’t have the words to say how much I love you – but I don’t try to find them often enough.

Contents

Foreword

Fifteen Years Forward

Part One: Small

Yellow

Pink

Green

Red

Part Two: Smaller

Purple

Watercolour

White

Why? Take One

Brown

Orange

Beige

Blue

Gold and Silver

Crimson

Black

Pink and Purple

Technicolour

Orange and Black

Emerald

Grey

Part Three: BIG

Colourless

Why? Take Two

Part Four: In Between

Yellow

An Apology – and a Thank You

Acknowledgements

Foreword

MY BIGGEST FEAR in writing this book – and writing it honestly – was that it would serve the notorious ‘cheat-sheet’ purpose often attributed to eating disorder memoirs. I feared it would be thumbed through by others as vulnerable as myself and dissected in search of tips on how to be ill. Why to be ill. Why to stay ill. It would be easy for me to say that my story doesn’t encourage this sickness emulation because of the ‘gritty detail’ I include about being so suffocated by anorexia that I was nothing more than a shivering, miserable bone bag, but I know this would be a copout. Perhaps it can only be understood by one who has been under the thumb of disease, but there is a voyeuristic something about anorexia nervosa which makes sufferers crave its gory, ugly depths. Fainting in public? Yes please. Fur from head to toe? Love it. Nasogastric tube? I’ll take two. I’ve read book after blog after Facebook post crawling with ‘Oh-woe-I’m-so-very-skinny-and-sad’ (usually accompanied by a melancholy picture of the writer, contorted grotesquely so as to give the most alarming view possible of clavicles, hip bones and ribcage), and have now learnt that this is really nothing more than code-speak for ‘Oh-look-at-me-and-my-suffering-bet-I’m-thinner-than-you-beat-that-(suckers)’.

I made two decisions when I started the feverish typing which eventually spooled into My Story; one easy, the other difficult. The easy was to leave out the numbers; I don’t say what I weighed at my lowest, highest or in-between-est; I don’t specify a body mass index (because any anorexic worth her salt has the weight-divided-by-height-squared calculation down to a tee and can use it as another point of comparison); I don’t talk in calorie numbers. Why would I want to? I know how ill I was – if, indeed, ‘illness’ can be measured at all – I don’t need to quote figures to validate it. This way, if it makes you feel better, you can by all means go through the book reassuring yourself that my lowest weight wasn’t as low as yours, that my BMI never dipped down as far, that my calorie restriction was not as extreme. I know how this illness works, so I know that if this is something you want to do then you are going to do it. Yes, I would urge you not to – it won’t help, won’t give you the fulfilment you crave nor quiet the voices raging in your mind. But if that’s the way you feel you have to read what I write, it’s not my prerogative to preach on the wrongs of doing so – after all, I’ve been there a fair few times myself.

The hard decision was to tell my story in its full, messy entirety. If I wanted an ideal story – one which could be neatly packaged, sealed and read by everyone I know – this book would stop at my eighteenth birthday. I would say something ambiguous about how I was Learning To Live With My Anorexia and that there was Light At The End of the Tunnel and talk about rebirth and lambs springing (and so on and so forth). My ideal story would not involve the giddying swing from starver to stuffer; it would not reveal the shameful momentum of my body hurling from one extreme to the other. But if I wrote my ideal story, I would have fallen into the trap of believing that if things are not said then they do not exist. By documenting, honestly and unflinchingly, my painful descent into post-anorexia bulimia nervosa, not only have I drained my story-self of all vestiges of secret, but I hope I have communicated the foul reality of eating disorders – the fact that one can so easily morph into another, and that it may be the second which hurls you, broken, to the floor.

If you want to read this book and think, ‘Gosh, it certainly sounds fun to have an eating disorder, maybe I should give that a go’, I can’t stop you. But I will say this: please don’t. I didn’t want to write a book in which I wallowed in my own suffering, I wanted to write a book which would give an honest insight into anorexia, bulimia, and, most importantly, the person behind these Big Bad Diagnoses. I wanted to write a book which conveyed the devastating damage caused by eating disorders, but not one which passed on this damage. To give people something to think about, but not something to emulate. Have I managed it? I suppose that depends on you.

Fifteen Years Forward

WHEN I WAKE up, it is because someone has poured poison into my mouth; sluiced it around my gums, dripped it between my teeth. The poison is sharp and spiky inside me; it arcs across my tongue, bitterness clawing at the insides of my cheeks. As the poison trickles over my soft palate, I absent-mindedly conclude that I will be dying today. Accept, with heavy boredom, that today, at fifteen years old and five foot three inches tall, I will be no more. Could be worse.

When, after long minutes of lying prone, swilling the poison from cheek to cheek, I realise I am not dead – or, indeed, in the process of becoming that way – I force movement into lazy arms. Disappointingly, I am still alive, but I do not yet know if I am safe. Reaching down to paw at the bones connecting foot and ankle, I clunk. An audible, hollow clunk between wrist-bone and hip-bone, the latter standing erect, like a guard between torso and pelvis. I run my fingers from knee bones to ribs, pausing only to press down into the well of my stomach, feeling for my back bone through the paper-skin. It is there. All of my bones are there, present and correct. I am safe. The guard must be pleased. As my busy fingers come to rest, curling themselves over the tops of my collarbones as they once clung to monkey bars, I replay the clunk over and over in my head. The sound of nothing-against-nothing. If I had the energy, I think I would smile.

Head cleared momentarily of body-guilt, I can deal with the supposed attempt on my life. Shorn of the romanticism of half-sleep, the sourness swamping my mouth is banal: ulcer after ulcer, chomped down upon by hungry night-time teeth, has oozed a putrid river of pus while I slept. Morning after morning the surprise awaits me; a reward, perhaps, for completing another 24-hour starvation stint. I mentally congratulate myself on no longer being disgusted by my leaky, rotting body: today, I don’t taste sour suffering, but the piquant tang of victory. Three months and counting, now; three months without a meal; a snack; a celery stick; a sip of milk. I don’t do starvation by halves. Ninety-three 24-hour stints and still going strong.

Swinging peg-legs from bed to floor with energy I don’t possess, I observe the feet protruding from my two-pairs-of-leggings-under-two-pairs-of-extra-thick-fleece-lined-tracksuit-bottoms pyjama alternative. Today the feet are wearing their most luminous mottled magenta, blending stylishly to blue at the tips of the toes. When I press a thumb down hard onto the left ankle, the white circle it leaves remains illuminated for ten, twenty, thirty seconds, my heart too lazy to pump the blood back to it with any great haste. Scornful of the lazy heart, I battle to the bathroom through the black scum which descends whenever a too-fast progression from sitting to standing prompts a blood pressure plummet. I feel momentarily dizzy – disorientated by the brume swamping my field of vision – and wonder whether consciousness will now evade me. But no. I survived an attempted assassination this morning, and now I am invincible.

Standing, twig fingers gripping the sides of the bathroom sink, I look hard into the eyes of a person I recognise less and less each day. Blood vessels worm their way across the whites of her eyes like tiny red maggots. Her head hangs off-centre, neck muscles too wasted to hold it straight: puppet-strings too spindly to animate their marionette. The skin on her cheeks is grey, stretched tight like the top of a drum, cheekbones ready to break through the surface each time she opens her mouth to speak; breathe; eat. (Ha. Good one.) I look at her, with her bruised bag-eyes and flower-stalk neck, and I wonder at what point she became me. At what point I became her.

And then I put on my other eyes, and I look at her again. I look at her, with her bloated, fluid-retaining abdomen. I look at her, with her slack, flopping skin. I look at her, chipmunk cheeks bulging with poison, and there is a Voice. A Voice which sounds like metal scraping metal; like the strangled cry of a trapped, mangled animal. And The Voice says:

‘Fat.’

Then I yank brittle hair behind ringing ears and lean forwards and spit. I spit with my eyes closed, body gagging and dribbling and bringing up gush after gush of cheek-skin, bile, sour, dead-tasting pus.

My mouth smarts. I rinse it out with cold water; rinse, spit, rinse, spit, rinse, swallow. Sour. Retch.

My eyelashes are spiky with moisture and they stick out straight, like clusters of spider-legs glued to my lids. Through the film of wetness, I look down at the mess of sickness splattered in the sink.

Yellow.

Small

Yellow

IN THE SUBURBS of London, on the last day of 1993, terraced houses snuggle up close and another baby – a me-baby – is added to the masses already roaming the streets in their Mothercare perambulators. I have a lopsided mouth and am bald for a long time, but eventually hair grows: white-blonde and fine as gossamer. I have full, pink cheeks and threads on my arms where flesh meets flesh. I have a home and a cot and a Mother and a Father called Mummy and Daddy. I am bonny and bouncing and comically well. Everything has a place, and everything is in its place.

Mummy cuddles and kisses and carries me as much as she can, trying to do the Continuum Method. She breastfeeds for years, wanting to be as close to me as possible. Daddy is distant – yellow-white hair shrinking back to where the top of his head pokes out, bare, like an island. A fleeting presence. Daddy doesn’t think much of babies; when he was young he did the routine of cots and bottles and nappies for the first time, with the mewling bundles which became Half Brother and Half Sister and the partner who became The First Wife. By the time I am born they have splintered off and receded back into the mysterious land of The Previous Relationship, but Daddy still sees them often and carries around a ‘been there, done that’ attitude to small children. But Mummy has not been there or done that. For Mummy, I am the first and the most treasured. Daddy finds this treasuring irritating. As a tired, temperamental infant I look through the bars of my cot-prison and wail with the need to be comforted; cuddled; loved. There is a hunger inside which I don’t have the words to articulate. I am shrill and needy and want Mummy – all of her, all the time – but Daddy wants her for himself. Behind the cot-prison bars, I bawl. After minutes which gape into hours, I am exhausted by the flow of hot, fat tears. My eyes grow heavy and I am nearly asleep when Mummy lifts me into warm arms. Mummy needs me like I need Mummy. Mummy needs to be needed.

I grow and thrive from Baby to Toddler: stubby legs and a round stomach and a halo of thin-thin hair. I talk early and a lot. When I am only two I say things like: ‘Well, that is a good compromise.’ I make everyone laugh and Mummy is proud, but she is also worried. I am bright and able but also brittle and anxious. I don’t sleep. I cling. I cannot cope with the unexpected, or with things going wrong, or with Transitions. When Mummy drops me at playgroup the corners of my mouth jerk downwards and my eyes twinkle with tears – ‘No, don’t WANT to stay!’ – but when she picks me up I am cranky and cold, turning my yellow-dungareed back on her and clinging to the teacher’s hand – ‘No, don’t WANT to go!’ Mummy says I live in a little world where the weather is constantly changing: beatific sun or devastating rain, rarely much in-between.

When I am three and flexing my knees for the leap from Toddler to Girl, another baby happens. Sister. I am pleased to have a sister but also worried because I like having Mummy all to myself. I kiss and cuddle Sister, but I bang my doll’s head on the table and shout at it. Mummy talks on the telephone in big, worried words like ‘Displacement’ and ‘Pent-Up Aggression’ when she thinks I am engrossed in the neon world of the Teletubbies, and says to her Phone-Friend: ‘Can I borrow your copy of Siblings Without Rivalry?’

When I start school I decide I must most definitely be a Girl now. I wear a grey skirt and a white shirt and a soft blue cardigan and feel Very Grown-Up. In Reception, I try to say the most and know the most and answer most of the questions Teacher asks us when we sit on the carpet, frog-legged, close enough to one another for the nits to leap from head to itchy head. I get given a special little red book for Literacy with all lined pages because I write more than can be fitted into the normal Reception books, which have lots of blank space for silly old pictures. Teacher says it is unusual to be able to write so much when you are so small. I glow inside. Usual sounds so grey and wet. I am unusual. Un-usual. It is sparkly and exciting.

In Years One and Two and Three and Four I get bigger and rounder and better. My insides sometimes scrunch and cower – when I can’t remember my times tables; when tetchy teachers deliver whole-class scoldings which seem conspicuously, pointedly addressed towards me; when the playground feels like a cold, lonely concrete cage full of noisy, shouty children who are not my friends – but I plaster over their squirming with layers of crumbly confidence. I can’t afford to be as small and scared as I feel; I have to be Perfect. If I’m not Perfect things are topsy-turvy and back-to-front and itchy-scratchy and wrong. If I’m not Perfect, no one will like me. If I’m not Perfect, nothing is in its place. I count the ticks in my exercise books, covering up crosses with chubby fingers, pretending they aren’t there. Hating the way they tarnish me. I speak in a big, loud voice, so in Class Assembly I usually have the biggest part: one time I am a cat sitting on top of a roof and another time I am the narrator (there are lots and lots of words to learn that time). I am Mature and Responsible, so I am often the one who gets asked to do errands for the teacher. I work hard at perfecting my Mature-and-Responsible skills, because I want everyone to be proud of me.

Being Perfect is especially important now, as by this time Sister is getting bigger every day, starting in Reception and nipping at my heels. Sister’s growing up makes me angry. I can’t say whether the anger is directed at Sister, for trying to steal the limelight, or at myself, for not being exceptional enough to hold onto it. I suspect the latter – I am quickly learning that most problems can be traced back to faults within myself. ‘Please, please don’t let Sister be the star’, I think as I curl up, safe in the privacy of night-time. ‘Please, please don’t let her be better than me.’

At home, Mummy is kind and warm and Sister and I want to be with her all the time. She is all the colours of an autumn leaf, I think – short brown hair and kind, pretty brown eyes. After years of sunlight, her skin has been dyed mottled brown too: soft, weather-worn skin which hangs looser and looser as the years go by (I like to pinch it softly, rolling it between the pads of finger and thumb, puzzled by the way my own flesh springs stubbornly back into shape after the same manipulations). I am also fascinated by the moles which speckle Mummy’s arms – the same moles which colonise my shoulder blades, soft and brown and underdeveloped on my small form. Mummy’s moles have sprouted with age, just as lines have gently furrowed themselves into her face over the years, deepening each time she smiles wide enough to reveal the tiny gap between her front teeth. Sometimes I watch, transfixed, as Mummy bites into a piece of toast and butter comes through the tooth-gap.

While Mummy has a soft, ex-baby-house stomach on her slender frame, Daddy is normal-sized all over, but to me he seems enormous – tall and towering. Like Mummy, his face is patterned with lines, criss-crossed like roads on a map, from years of smiling and laughing but mostly of frowning. Sometimes, after a long time of frowning, Daddy takes the big, square glasses off his nose and rubs his eyes with his knuckles as if an unnamed Something is making him very, very tired. I see him do this a lot at home, and I think perhaps I make him very, very tired.

Daddy is In Television, which sounds like ON Television but is not as exciting. Daddy is a di-rec-tor, bossing everyone ON television about from behind the cameras. The stacks of scrap paper which bear my crayon-crafted works of art are leftover scripts, and the concept of the world existing through a camera lens – as a series of wide shots and closeups – is one woven into the fabric of my DNA. I am proud of the scrap-script mountains in my house, and proud of having a Daddy In Television. I boast about it to everyone at school, but really it is not anything to boast about because it seems like there is just not enough Television to go round these days and Daddy is often out of a job. And this makes him cold and sad and grey.

Mummy is fun and Daddy is strict. Mummy lets me and Sister stay up late and sometimes even lets us wrap up warm and takes us out for walks when it’s pitch-black-night-time outside and this makes me feel special and grown-up and important. Daddy tells me off a lot – for Talking With My Mouth Full and Dropping My Coat On The Floor and Not Making My Bed – and this makes me feel horrid and messy and lazy. I sometimes hear Mummy and Daddy fight about how Mummy is fun and Daddy is strict. There are more big, worried words then, like Unified Front and Lack of Discipline. I do not understand them, but they sound cold and dangerous. But we are a good little family of performers, following the script set out for us to the letter.

Scene One: The Dinner Table

[Shot of family – Mummy, Daddy, Nancy, Sister – sitting eating dinner together]

Nancy (animated)

Today at school when it was lunchtime at school and –

Daddy [flat]

Don’t talk with your mouth full.

Mummy

What happened at lunchtime, sweetheart?

Nancy

It was at school and I was on the steps and then I was going to come down but –

[Sister throws handful of mashed banana from high chair onto floor]

Mummy

Oh dear, what happened there, poppet?

[Daddy sighs. Sister gurgles, smiling. Mummy strokes her hair. Nancy pulls Mummy’s skirt]

Nancy (almost shouting)

Mummy, it was at school and I went down the steps but then I got a bit of my shoe – like this bit here – this bit of my shoe – stuck on the step and it was lunchtime and –

[Daddy sighs again. He leaves the table. Mummy wipes Sister’s face, making ‘listening’ noises in Nancy’s direction]

Mummy

Really, darling? Is that right? What a funny thing to have happened!

[Nancy slumps down in chair, chewing her cardigan sleeve]

Nancy’s Inside Voice (voiceover)

No. That’s not right. I hadn’t even finished. Nobody is listening.

Nancy (very quietly)

Yes. So funny.

[CUT]

As well as Mummy and Daddy and now Sister (whom I am still not all that sure about), Granny and Grandpa occupy a cosy corner of my life. These are Mummy’s Mother and Father – Daddy’s family are all either dead or living far away in mysterious places like The Other Side of the Motorway. Mummy’s family all live just around the corner so they are the ones I see often and spend most time with, and this seems to make Daddy cross. I don’t really understand why.

Granny and Grandpa have a big, long garden with a bay tree in the middle, and in summertime there is a sprinkler and tiny bare bodies run in-out-in-out, dripping onto the sitting room carpet and knowing that the drips will not be met with scrunched eyebrows or cross voices. One weekend, Mummy says, ‘Do you want to take any toys with you when we go to Granny and Grandpa’s house?’ and I say: ‘Don’t be silly, Mummy. Granny has her own toys.’ And she does – baskets and baskets of toys, and offcuts of fabric for wonky cross-stitch and a shed for carpentry and a table set up for painting in the attic and blackberries to be picked from the garden hedges. Granny has everything and knows everything and does everything she can to keep me and Sister occupied, and though, like Daddy, she wears glasses – enormous glasses which hang on a chain round her neck and magnify her eyes like an owl’s – she never has to take them off to rub tired eyes, even though she is old. Granny never seems tired at all – she is always ready to go out on trips or play games or just listen to the things I have to tell her, while Grandpa sits in Grandpa’s Chair and Sister falls asleep on his knee.

I grow up falling asleep in dressing rooms, swinging on the handles of stage doors and assembling make-shift step ladders out of yet more scripts, because Granny and Grandpa are In Theatre, and in this case really IN theatre, not just behind the scenes making things happen (which is what Mummy does – or what she did before mine and Sister’s advent). I am proud to be part of a Theatrical Family, and pretend to enjoy the productions of The Cherry Orchard and Separate Tables in front of which I doze at five, six and seven years old. I think it is Very Special Indeed to be part of such a mysterious, sparkly world – to see people on a stage and then, minutes later, see them again, the same and also different, back in Real Life – but I also find the thought of being up on a stage with millions of people staring at you very scary. They might not like you, might laugh at you for being too small or too fat or too ugly. You might be on the stage with lots of other people, and the other people might be better than you, and the lights might get in your eyes, and you might make a mistake and not be Perfect. And what then? But performance surrounds me, and I feel the weight of expectation like a leaden scarf around my shoulders.

Scene Two: ‘When you grow up…’

[Grown-Ups cluster around a seven-year-old Nancy. They are loud and exclamatory; she is tense and quiet]

Grown-Up One

So, would you like to go into The Business when you’re older?

Nancy

Oh yes, of course…

Grown-Up Two

And you’re planning on following in the family footsteps, I assume?

Nancy

Absolutely, yes…

Grown-Up Three

And you’ll be the next actress in the family, I hear?

Nancy

Definitely…

Grown-Up Four

It’s in your blood, isn’t it? I imagine all you want to do is perform?

Nancy

Yes, yes, definitely, I just want to act…

Nancy’s Inside Voice (voiceover)

Yes, yes, please like me, I just want to be what you all want me to be…

[CUT]

There are sad bits interwoven with the sparkle of my world during The Young Time. Mummy and Daddy get cross with each other and retreat into themselves, flexing small, tight muscles of resentment. People die – indeterminate uncle/aunt/family friend characters whose passing engenders in me not grief, but an uneasy sense of foreboding, scrabbling like an unruly ferret at the bottom of my stomach. (‘Please don’t let Mummy die,’ I whisper at night, eyes tight shut, fingers and toes crossed, willing the prayer to wrap a shield around her, to preserve her as the solid centre of my Little Girl World. ‘Please, please don’t let Mummy die.’) I sometimes feel sad and can’t explain why; Mummy sometimes cries and I don’t understand why; I feel a deep-seated fear – of Daddy; of The Future; of not being Good Enough – and wish I knew why. But the overwhelming colour of my early world is yellow: bright, warm, welcoming yellow. Playing on the streets, falling down, blood trickling down into frilly white socks and strong, safe arms lifting up, up, up. Twenty pence pieces clutched in hot hands, then exchanged for technicolour sweets in cardboard tubes which stain fingers like paint, their purchase echoed by the ting-a-ling of the bell on the door of the corner shop. Days spilling into nights; months spilling into years; babies spilling into boys and girls.

Yes; The Young Time is yellow.

Pink

Christmas – 1998 – Five Years Old

Excitement fizzles in my tummy from the first of December, pop-pop-pop, effervescing like bath salts. Christmas is everywhere – in the smell of the cold days, the lethargy of the end-of-term lessons at school, the thrill of popping open a new cardboard window every day to reveal a picture of a shepherd, or a star, or a bulging stocking. (In an uncharacteristically wholesome way, Mum disapproves of chocolate advent calendars. Sister and I grudgingly make do with pictures, gazing wistfully at friends’ Cadbury alternatives when we go round for tea.) There is a double calendar-window on Christmas Eve, opening like the big doors out onto the garden at Granny and Grandpa’s house, and that night I cry and cry and panic because my brain and my tummy are tick-tick-ticking too fast to let me sleep but I know that if I don’t sleep I’ll be tired on The Big Day and then Everything Will Be Ruined.

Christmas is full of fizzy feelings. Frenzied excitement so heady it’s like champagne bubbles frothing in my nose. Real champagne bubbles which do froth in my nose and make me feel gloriously, glamorously Grown-Up. Crushing despair as I clamber into the car to go home from Granny and Grandpa’s house and realise that it’s all over for another year.

I wear a pink, flouncy satin dress. A party dress. The fabric is soft against my skin and makes a snick-snick-snick noise when I move. I am dizzy with the pride of Dressing Up. I get a fairy costume from my cousins this Christmas, with a soft top and long, gauzy skirt, dotted with silver stars. And wings. AND a wand. I go out of the room and Biggest Cousin pulls it over my head, over my grubby cotton vest and wrinkled green tights. I am transformed. I glow.

I want everyone to exclaim, ‘Golly gosh, it’s a fairy!’ when I go back in. I have it all planned out in my head. It is going to be fantastic. But when I tell them – very strictly and exactly – what I want them to say upon my grand entrance, I can see they are laughing at me. It is not mean laughing, not ‘ha-ha-we-think-you-are-stupid’ laughing, just ‘ha-ha-you-are-so-eccentric-and-so-very-young’ laughing. But I don’t want to be young, and I don’t want to be funny. I don’t really see what there is to laugh about, because a fairy coming into your sitting room on Christmas Day is magical and exciting (and possibly even a bit of a shock), not funny. I think the whole lot of them need to take the whole thing a lot more seriously.

I come in and wave my wand and everyone says, ‘Golly Gosh, it’s a fairy!’ but it feels all wrong. Their voices are too loud and I have to put my hands over my ears because I hate big noises. They are acting surprised but I know they aren’t really, because they all saw me unwrap my fairy costume and saw me go to get changed. They know I am not a real fairy – just an ordinary, boring little girl. I don’t even feel like a fairy anymore. My Big Moment has fallen flat and Everything Is Ruined.

When I am in Year Five our class is moved into one of the new buildings, out in the corner of the Key Stage Two playground, which is very exciting indeed. The new buildings are clean and smart, with carpets which don’t scratch your bottom when you sit on them and whole walls of windows. My Year Five classroom is at the end of the corridor and is painted pink all over (except for the bit by the sink which has gone a sort of greeny-dishwater colour because that’s where the roof leaked and it got damp). All the girls love being in The Pink Classroom, but the boys say they hate it and pretend to be sick.

I like being in the new building for lots of reasons; the classrooms are nicer-looking, and the painty smell is sharp and exciting, and we don’t have to use the horrible Years-Three-and-Four toilets anymore. But most of all I like being in the new building because it feels like a Fresh Start – a chance for everything to be bigger and brighter and better than ever before. I have a new uniform too; a new grey pleated skirt and a new white polo shirt (which doesn’t have any baked bean stains down the front) and a new blue sweatshirt with the yellowy-orange school logo in the shape of a tree on the chest. I feel very big and very bright and I am determined to be very much better than ever before.

Our Year Five teacher was supposed to be Miss D, but then at the end of the summer holidays she broke her leg, so we have to have Supplies. The Supplies are mostly Australian or New Zealand-ish (I can’t tell the difference), and mostly they are very nice. Miss B is small and rounded with tight, curly hair (she gives us sweets when we get enough house points), and Miss C is tall with fair hair (she teaches us a really fun game where you have to think of lots of things beginning with the same letter in one minute. I am very good at this game). But they can never stay very long; usually as soon as we get used to one they are replaced by another. I can’t cope with all this change. It makes me feel unsafe.

I have lots of friends in Year Five: Freckly Friend, who is one half of twins and used to live on my road; Tall Friend, who has pale, pale skin and is very tall and sometimes shows me steps from her Irish dancing class at playtime; Pointy-Teeth Friend, who laughs very loudly and very often and sometimes gets me into trouble. I don’t have any friends who are boys, because that wouldn’t be right, but Freckly Friend and Tall Friend and Pointy-Teeth Friend and I talk a lot about who we fancy and who everyone else fancies. I don’t really fancy anyone, but I choose a boy at random and pretend to swoon, just so I don’t feel left out. It is important not to be left out.

At school we do Literacy (in blue books) and Numeracy (in green books) in the mornings, and we have red books which we use in the afternoon for ‘Topic’ (which Mum says is ‘just a modern way of saying Geography and History and Science all together’). Sometimes our Topic might be The Victorians, sometimes it might be The Water Cycle, sometimes it might be Space. In our red Topic books there is one page lined for writing and the other plain for the picture, like in the silly baby books I outgrew years ago.

One Tuesday afternoon, when our Topic is The Human Body, we draw two bubbles with lots of sticky-out lines sticking out. We have to see if we know the difference between the things we need in order to live and the things we might think we need but actually we just want.

My Topic book is very neat and my bubbles are very Perfect. It is important for my work to be Perfect because work is like a mirror held up to my round face: if my work is Perfect then I am Perfect. Or closer to being Perfect. As well as my flower-patterned pencil-case and pink plastic water bottle, since Year Three I have been bringing a secret supply of Perfection-Correction Tools to school: a tiny notebook of white paper, sharp little scissors and a gummy glue-stick. This way, mistakes don’t need to be there for long, and I never have to even think about Crossing Something Out – the very thought makes me feel sick. So messy. So permanent. My way is much better – with a snip and a stick, it is like the imperfection never even happened. Sometimes, heart pounding with dishonesty, I do my snipping and sticking trick with the crosses in my Maths book; glue white scraps over the horrid, messy marks and pencil in a neat column of ticks instead. When there are no crosses in my books, I feel clean. Neat. Everything is in its place.

So far I have not made any mistakes in any of my work today, and I want it to stay that way. Topic is easy and I know all the answers. I know we need oxygen and water and sleep and food. Just to live. I also know the things I want. I want to meet the cast of the Harry Potter films. I want a dress with beads round the neck and lace round the bottom from British Home Stores, like the one Tall Friend has. I want my own computer.

I chew the end of my pen, teasing the plastic into slivers between my teeth, but then I remember the story Freckly Friend told me about how once her little brother was sucking the end of his pen and all the ink went into his mouth and he had to go to hospital and nearly died. I stop chewing my pen. I look at my bubbles and at the shadow cast across the page by the soft flesh of my forearm; at the dimples which, like tiny valleys, punctuate my pudgy hands. There is another thing I know I want – perhaps even more than the dress or the computer (though I’m not sure whether I want it more than I want to meet the Harry Potter cast) – but somehow it doesn’t feel as easy to put down on the page as the other things. While it is something I yearn for desperately, it’s not concrete like clothes or commonplace like Harry Potter obsession. It’s something which, when I think of it, makes me feel somehow sad and embarrassed, though I can’t explain why. I consider keeping it locked away inside, but reason that unless I put it out there – make it known to the world that this is one of my most serious wishes – there is no chance of it coming true. So I scribble it down, and as it spools itself out onto the page in my wobbly joined-up writing I hear the words spoken by a brittle, whining voice. The Voice feels prickly in my head, and I slam my red Topic book shut, slamming away the whining and the spiky, complicated final ‘want’.

‘I want to be thin.’

Inside my red Topic book I think my work looks very neat and I think I will get a sticker for it. I have been sneaking a look at Girl-to-the-left-of-me’s bubbles and Boy-to-the-right-of-me’s bubbles and Girl-across-from-me’s bubbles and I think mine definitely look the best. After all, the others haven’t even really been trying very hard: Girl-to-the-left has been seeing how far back she can tip her chair without toppling over (not very far, it turns out: now she has a wet paper towel on her head and is sniffling) and Boy-to-the-right has been drawing Pokémon on the table (which he will get in trouble for later) and Girl-across has asked to go the medical room three times and the toilet twice (though Miss only let her go to each once). I’m not surprised their bubbles-with-sticky-out-lines look a bit wonky and rubbish.

I don’t think much else apart from this. I don’t think about how to get thin any more than I plan a trip to the Harry Potter Studios or a PC World raid. At nine years old, I have small thoughts and small plans, and they fit inside small bubbles without spilling out. I don’t think about next year, or next month, or next week. I don’t look at my two bubbles next to each other, so I don’t think about the irony of the fact that the sticky-out line saying that I need food to live is right next to the sticky-out line saying that I want to be thin.

When we go out to play, Friends and I cluster in our favourite corner of the Years-Five-and-Six Playground, taking it in turns to race across to the water fountain and back to see whether we can make it without getting hit by a football (Tall Friend can’t, so we take her to the Medical Room). At lunchtime I eat three small strips of white-bread-no-butter-crusts-off ham sandwich and some red grapes and a chocolate biscuit. In the afternoon we have Music and we play on the xylophones. I have a Loud Day, shouting across the football pitch at playtime, laughing noisily at lunchtime, bashing my xylophone so hard in Music that one of the keys flies off. I say sorry to the teacher. I don’t say that I only did it because I was trying to block out the continuous, thrumming chant in my head: ‘I want to be thin, I want to be thin, I want to be thin.’

Green

Christmas – 2003 – Ten Years Old

There are things I enjoy about being Grown-Up at Christmas – I like giving presents that I chose myself, because I feel glowy when people are pleased with them – but there are more things I don’t enjoy. I hate the feeling of getting too old for babyish traditions; I hate niggling worries in the pit of my tummy about all the mountains and mountains of money being spent; I hate lying awake at night with my mind curling itself into tortured knots, fearing I might start my period on Christmas Day (we learnt about ‘Men-stru-ation’ in PSHE the other day and I think it sounds horrific).

I don’t enjoy how I look at Christmas. I know I’ve probably been fat ever since I was little, but back then it was an endearing, soft sort of fat. Chubby. ‘Cute’. When I was in Year One, my class was in the school nativity play as the animals, and all the Year Sixes used to say to me: ‘Aww, look at your chubby cheeks! You’re so cute!’ But now I’m TEN – we’re having school discos and everyone is worrying about what they wear and how they look – and the fat doesn’t feel cute anymore. It feels indecent. Embarrassing. It sneers at me. I try to pretend that I don’t care, that looks don’t matter to me, that I’ll lose weight naturally when I get to being a teenager because, after all, I really don’t eat that much. Incidentally, none of it is true. I do care, painfully, so much so that sometimes I can hardly breathe for caring; beneath the standard it’s-what’s-inside-that-counts façade, looks do matter to me; I do eat a lot, more than I should do or need to, because even by ten years old my relationship with both the size of my stomach and what goes inside it is skewed (the humiliation of being known from birth as a ‘chubby kid’ leading, ironically, to comfort eating.)

On Christmas day I wear a black skirt and a black jumper because it is the only outfit I trust to fit me. The fabric is scratchy against my tight skin. I cry when skinny Sister wears a party dress. She sparkles. I skulk. I eat a lot, all day. I wonder why I never seem to get full.

In Year Six, we have The Year Six Production. We are doing a musical and I have a big part with lots of lines and a solo song. This makes me feel good as I know that all the girls in Year Six wanted to get the big part but we had to do auditions and they only chose one person so I must be the most Perfect. Imagine that. It’s basically like being The Queen. I learn all my lines, and then I learn all the stage directions, and then I learn everyone else’s lines, and I mouth them when we are rehearsing just in case anyone forgets. I want everyone to see that I am Perfect at learning lines.

Sister is proud that I am playing a big part in The Year Six Production, and I feel ashamed of my inability to mimic her selfless generosity – when good things happen for Sister, my go-to reaction is jealousy, not pride. Four years ago, in her end-of-year report, Sister’s Nursery-school teacher wrote that Sister ‘definitely has a career ahead of her as an actress or dancer’, and it sparked a rage in me which still bubbles at times. ‘Performing is my thing, Sister,’ I think. ‘I’m the older one, it’s me who’s supposed to be the Star. Stop treading on my toes. You’ve already got everyone cooing over you for being The Baby of The Family – isn’t that enough?’ Mum tries to soothe me when I put on my green eyes, telling me that ‘Sister being talented in the same areas as me doesn’t detract from my own abilities’, but I don’t agree – it is as if, at birth, Sister and I were given a finite amount of ‘Specialness’ to share, and the more she takes the less there is left for me. The more she grows and shines, the more I shrink and tarnish.

The Year Six Production is a Very Big Deal, so we all have costumes. This is the only bit I don’t like, because I know that I am fatter than most of the other girls in Year Six. When I have to go and try on my costume in the Years-Five-and-Six toilets my heart goes bang-bang-bang in my ears and my cheeks feel hot. My dress is green and silky and very tight, but it does fit. Just. While I struggle to get Green Dress off again, I think again about how I would like to be a little bit thinner. Just because I want to be an actress when I grow up. Just because I don’t want always to be worried about my costumes being too small. Just a little bit thinner. Thinking this makes my throat prickle and tighten. I don’t know why.

When we rehearse the next day I forget about the Green Dress and the Fat Feelings. Everyone says I sing my solo really well and know my lines really well. The teacher in charge says I am very reliable and am doing really well. I don’t care about Too-Tight-Green-Dress anymore. I am Perfect; everything is as it should be. Everything is in its place.

I don’t want to leave my Small School, and on the last day my eyes are like leaky taps. I won’t see many people from Small School at Big School because I’m going to a Private Girls’ School, not the local comprehensive. Dad wanted me to go to Private Girls’ School because he is preoccupied with my being successful, but the whole thing makes Mum anxious because we haven’t enough money for those horribly high fees, no matter how many scholarships and bursaries we throw at them. By now, Mum has retrained as a primary school teacher, but even the renewed defence of a double income is trounced in the war against Money Worries. Uncharacteristically, I am in agreement with Dad: I do want to go to Private Girls’ School. I tell my parents that I think I will fit in there; that I would be too scared to go to the big, rough, comprehensive; that I would rather go to school with just girls than with girls and boys. I don’t tell them that really I just think going to Private Girls’ School (which you have to pass a Very Difficult Exam to get into and where you have to wear a Very Smart Uniform) will make me feel Special. I need to shine in the same way other people need to sleep and breathe, but I have a feeling this is one of the things Mum would regard as ‘worrying’. When I try to talk to her about my overachievement obsession, she does her worried look and says things like: ‘Sometimes it’s OK not to be perfect, you know, Nancy.’ I hate it when people say things like this because I know it’s not true: I do have to be Perfect. If I am not Perfect, I am flawed. If I am not Perfect, no one will like me. If I am not Perfect, I am nothing.

I pass the Very Difficult Exam; Dad gets a new job; Mum purses her lips and looks doubtful about the whole thing, but it is too late – the place is accepted, the starchy new uniform is bought. Before I start my first term, I go to an Induction Evening where we sit in our new classroom and do Icebreaker Activities. Private Girls’ School also has a Private Junior School, so a lot of the girls in my new class already know one another. They cluster together in noisy clumps, giggling as they swish long, straight hair over their shoulders. I tug hard on the end of one of my short plaits, willing it to sprout longer and magically attract me a few friends at the same time. It doesn’t work. I feel left out and don’t really want to come to Private Girls’ School anymore. In the classroom I sit next to a girl from Private Junior School who has a long, blonde ponytail fastened with a green scrunchie. She is Very Pretty and Very Confident and Very Thin. I feel very plain and very shy and very fat. When I get home I cry hot tears and tell Mum about pretty-thin-confident Blonde Girl. Mum looks even more purse-lipped and doubtful, but she wraps me up in soft arms and tells me that she knows how much I struggle not to feel bad about myself – how easily I fall into thinking I am not-good-enough; that she was also chubby at my age; that if I truly think it would help me to feel better in myself we could think – together – about ways in which I could start to Do Something About The Weight. Despite the warmth of soothing words all around me, I am cold inside. My chest goes tight and achy. I hear Mum saying that I don’t need to be thin, that I have other things going for me, that I am clever and talented and kind. But I think actually I would rather just be thin.

When I am in bed that night, the words come back to me, claws out, pinching and scratching and rearranging themselves into cruel, caustic loops. They whip around my head, battering at the sides of my skull, except this time they don’t articulate themselves in Mum’s voice, or my voice, or any voice I recognise. Or – at least – I don’t think, at first, that it is a voice I recognise. It is a voice which is small and shrill but spiky all over, like a cross hedgehog, and it flings itself around inside my head, angry and gleeful and maniacal all at once, and as its pitch rises to a shallow mewl I realise that it is familiar after all. It is not just a voice; it is The Voice. The whining, grinding ‘I want to be thin’ Voice which I thought I had buried deep in the annals of my red Topic book. I was wrong. It escaped. It escaped, and it grew.

‘Not good enough. Bad. Chubby. BAD. Do something about it. The Weight. Bad. Chubby. The Weight. Not good enough. BAD. THE WEIGHT. NOT GOOD ENOUGH. DO SOMETHING ABOUT IT.’

Red

AT FIRST, THINGS are hard at Private Girls’ School (PGS). It feels like everyone there knows everyone else, but no one knows me. Even the other girls who are new to the school this year already seem to have become intricately arranged in neat social circles, sniggering together in lessons and snarling up the lunch line with their tight, secretive huddles. I am not a member of any of these secret clubs. In lessons I clutch my pen so tightly the tip of my index finger whitens, trying to make my joined-up-handwriting Perfect. Trying to ignore the empty seat beside me. In the lunch line, I pretend to count the change in my purse, desperately looking busy to escape feeling lonely. As well as the friendship frustrations, I am struggling to keep up with the relentless pace of academics and extracurricular activities; the niche of ‘Best’ – which, mere months ago, I slotted into so neatly – now seems aeons away. A lot of the time, I feel like The Worst. The difference between PGS and Small School is overwhelming, and I am overwhelmed.

After the first few tearful weeks, things start to settle down a little. I find that I still have moments where I can feel Perfect, like when I sing all by myself in a concert and everyone says it was Very Good, or when I win a box of Quality Street for an Art Competition. But PGS is not the same as Small School because I have to work very hard to carry on being Perfect. At Small School I could just float along and it wasn’t difficult to be at the top, but at PGS I have to paddle-paddle-paddle and often I still can’t quite break the surface. This scares me. This is not how it should be. Nothing is in its place. I am good at English, Music and Drama, but I don’t get put in the top ability set for Science and Maths. All the confident, clever classmates do get put in the top set, and this makes me think that maybe I don’t really want any of them to be my friends.

Even putting competitiveness aside, making friends at PGS is not easy. Mum worries, as for the first few weeks I come home despondent, saying I feel I don’t fit in. I overhear her on the phone one night saying to another mother: ‘Nancy is very insecure in her relationships with other children.’ I don’t know exactly what this means, but I think it may have to do with the fact that whenever I alight on someone I would like as a Friend, I am immediately gripped by a conviction that this liking is one-sided; ridden with worries about my shortcomings. In friendships of three or more this ‘insecurity’ is particularly troublesome – Mum has already had to deal with years of my conniptions over ‘being left out’ and ‘so-and-so going off with so-and-so’ at Small School, and at PGS the feeling is ever-present and ever more intense.

Eventually, after the bumpy start, there are the beginnings of tentative, two-sided likings and even more tentative relationships. The first Friend has dimples and a slim, neat shape; another Friend has pointy teeth and takes me under her wing, like my stand-in weekday mother; another wears square glasses with heavy frames and sings in a lovely, husky voice. All of the Friends are clever, and most of them are pretty, and this means I spend a lot of time worrying about whether they are soon going to realise I am neither clever nor pretty and dump me. But days and weeks pass, and no date is set for the anticipated ‘dumping ceremony’; instead there are shared giggles and saved seats and ‘will-you-sit-with-me-today-at-lunch?’s and, after a while, cinema trips and friendship bracelets and midnight feasts at sleepovers.

When I go to Friends’ houses after school for tea I am always surprised – not by their palatial homes (I’m used to that bit by now), but by their dads. Bizarrely, to me, many of them have dads who seem to be almost as involved in their lives as their mums. My mind ties itself up in knots trying to understand these dads who come and welcome them when they get home from school; dads who they kiss and cuddle; dads who know all about their lives; dads who cook. I watch these spectacles of paternal behaviour and I don’t feel jealous exactly – more hollowly sad. I think, ‘My dad just sits upstairs at his desk and tells me off if I leave my room in a mess. My dad doesn’t get my dinner or take me on outings or put me to bed. My dad disappears at weekends to spend time with Half Sister and Half Brother from The Previous Relationship. I don’t think my dad even knows the name of my form teacher.’ I don’t feel neglected, because I have Mum to do all the parenting I need and I think my mum is better than all of Friends’ mums put together. But I do begin to see the unusualness of Dad’s absence from Sister’s and my upbringing.

The gradual stabilisation of friendships helps me feel a little better in myself, with my increasing understanding of Friends’ identities helping me come to cautious conclusions about my own. Motherly Friend’s petite stature belies formidable self-confidence, the like of which I feel certain I will never accrue. She is the sort of person of whom I am usually jealous, because everything in her life seems Perfect – her house is a mansion, she is the cleverest in the class, she wins the poetry competition and the singing competition and the public speaking competition – but somehow her offer of friendship to ‘one as lowly as I’ imbues in me not envy, but honour. On non-uniform day she wears blue jeans with flowers embroidered down the leg and her denim jacket matches, so it is clear that her life is completely and utterly sorted. My clothes never match because my life is not sorted, but I think I could certainly do with the sorted influence Motherly Friend offers.