11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Duncan Forrester's research on an Aegean island is interrupted first by the murder of a British archaeologist, and then by the outbreak of the Greek Civil War. The worship of ancient gods may provide a clue to the murderer, but in such a tumultuous time, little is what it seems.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Gavin Scott and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1 Sunset Over Athens

2 His Beatitude

3 Tin Face

4 The Speculations of Inspector Kostopoulos

5 Going to see the General

6 On the Waterfront

7 Into the White Mountains

8 Minotaur

9 The Hunter and the Hunted

10 Cyclops

11 Poseidon

12 Penelope’s Island

13 The Thumb of St. Peter

14 The Bay of Limani Sangri

15 The Pediment

16 Bitter Herbs

17 The Trio

18 The Gun Emplacement

19 The Legend of Count Bohemond

20 Vanishing Point

21 Aftermath

22 Into the Woods

23 The Field Telephone

24 The Man from Athens

25 The Windmill

26 Truth and Consequences

27 The Affair

28 The Choice

Afterword

Author’s Note

About the Author

Coming Soon from Titan Books

THE AGE OF OLYMPUS

ALSO BY GAVIN SCOTT AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

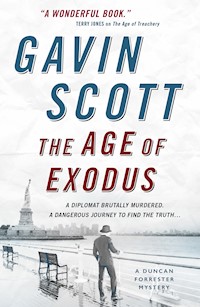

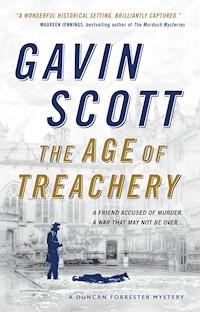

The Age of Treachery

The Age of Exodus (April 2018)

GAVIN

SCOTT

THE AGE OF

OLYMPUS

A DUNCAN FORRESTER MYSTERY

TITAN BOOKS

The Age of Olympus

Print edition ISBN: 9781783297825

E-book edition ISBN: 9781783297832

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: April 2017

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2017 Gavin Scott

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

TO MORRISON HENRY JACKSON

1

SUNSET OVER ATHENS

“We held them off for a week up there back in 1944,” said the press attaché, pointing up to the Acropolis.

“The Germans?” said Sophie.

“No, dear lady,” said the attaché, a pop-eyed man with a military moustache, “the Greeks.”

Sophie glanced at Forrester, puzzled. “I thought the British were on the same side as the Greeks,” she said.

“We were on the same side as the Greeks, yes,” said the attaché. “But not the communists.”

They were inching their way along Aeolos Street, which runs west from Stadium Street to the foot of the Acropolis, and every few yards the car had to slow down to avoid old ladies spilling into the roadway offering hot chestnuts, green-dyed cakes, black market cigarettes, candles decorated with pictures of the Virgin Mary, transfers of the crucified Christ to stick on your arm, and fireworks with which to celebrate Holy Week, 1946. Forrester had flown to Athens because, to his amazement, the Empire Council for Archaeology had finally given him the funds for his expedition to Crete. But it turned out there were people in the Greek capital who wanted to see him before he set off for the island, and the press attaché from the British Embassy had been waiting for them at the airport in a Lagonda, which must have been in use before Archduke Ferdinand went to Sarajevo. Possibly when the Archduke went to Sarajevo.

“During the war, of course,” said Forrester, “the communists were some of the best fighters. And we were all on the same side.” Every other house, Forrester noted, now seemed to be daubed with red communist slogans.

“That was then,” said the attaché, whose name was Lancaster, “but ever since the Germans left, the Reds have been trying to take over. Came as close as dammit just after I arrived, too, in forty-four. Hence the fight outside the Parthenon.”

“Which I imagine would have been a very good defensive position,” said Forrester.

“That’s my point, old chap,” said Lancaster. “Made you realise why the Greeks put the Acropolis there in the first place. It looks magnificent – but it’s all about power.”

Countess Sophie Arnfeldt-Laurvig’s eyes met Forrester’s in a secret smile. They were both savouring the delight of being together again after their brief, dangerous encounter in Norway. When Forrester had asked her if she wanted to come with him in the Cretan expedition he had held his breath, wondering whether he had misread what had passed between them during those tense, tender and almost fatal hours at Bjornsfjord, but to his profound relief she had responded to his invitation immediately. After four years of balancing the demands of supporting the Norwegian resistance and protecting the tenants on her estates from the German occupiers, she was eager to escape, and when they had met at London Airport it was as if they had never parted. During the flight to Athens she had clasped his hand tightly in hers, and though they had said little, it seemed that little needed saying. The war was over and they were back together again. It was enough.

Now they were being driven through what was left of the old Turkish bazaar, past alleys full of toymakers, shoemakers and coppersmiths, like something out of the Middle Ages. There was even a row of shops whose windows were entirely filled with buttons. Sophie smiled. “I must go to those shops,” she said. “In Norway, for some reason, it was impossible during the occupation to readily obtain any buttons.” Her English, lightly accented and perfectly pronounced, was composed of a slightly old-fashioned vocabulary once provided to the nobility of Europe through well-qualified governesses.

“Say again?” asked Lancaster. “Hard to hear through this din.”

Which was an understatement. The Greeks, Forrester had always felt, had a unique passion for noise. Radios blared from every open window, the street was loud with conversations being carried on at the top of voices, seconded by church bells, crowing cockerels, the clanging of trams and the roar of internal combustion engines. A motorcycle passed them with a deafening boom.

“Look at his exhausts,” said Lancaster, his fingers drumming the steering wheel. “I’m pretty certain that not only are those not silencers – they’re actually amplifiers.” The attaché’s Christian name was Osbert, which Forrester remembered reading somewhere, during the war.

Lancaster turned to Sophie. “So what was it you wanted to shop for, Countess?”

“Buttons,” said Sophie.

“Buttons tomorrow,” said Lancaster decisively. “Sunset tonight,” and swerved the car violently into the kerb beside a ramshackle taverna whose sign was almost hidden under a canopy of vines. “Hop out and grab a table.”

Moments later they were looking over the shoulder of the proprietor, an unshaven man in a shirt that looked as if it had not been washed since the German invasion, as he poured liberal doses of yellow retsina into well-chipped drinking glasses.

“It’s only going to last two minutes,” said Lancaster, “so keep your eyes open.”

Obediently, Sophie and Forrester fixed their eyes on the Acropolis.

“Watch how the last rays of the sun leave this hideous city in blessed darkness and just light up the hilltop.”

Sure enough, as post-war Athens vanished into the dusk, the marble of the Parthenon and the Propylaea began to gleam as if with an inner fire, and behind them Mount Hymettus turned rose-red.

“It’s perfect,” said Sophie. And it was. It was like a stage set, complete with lighting, which had been arranged for their delight two and a half thousand years before.

“Your health,” said Lancaster, raising his battered glass – and then paused and held up his hand in warning. “Have you alerted the countess to what this stuff tastes like, Forrester?”

“The wine has hints of pine resin,” said Forrester to Sophie.

“For which read emphatic overtones of the best turpentine,” said Lancaster.

Forrester smiled. “But you might come to enjoy it.” He clinked his glass against hers, and Lancaster’s, and as they drank, the sunset reached its climax. Sophie looked at Forrester, her eyes bright with merriment.

“My admiration for the ancient Greeks is very much increased,” she said, “if they built their civilisation while drinking muck like this.”

“They say this was the hour that Socrates took the hemlock,” said Lancaster, his long fingers caressing his silky moustache, “so you may be witnessing the last thing the old boy ever saw.” They watched in silence as darkness reclaimed the great temple, thinking of the snub-nosed, henpecked philosopher who had paid the price for questioning the gods four hundred years before the birth of Christ.

“Tell me more about your run-in with the communists,” said Forrester. “Some of them were probably chaps I fought alongside during the war.”

“Doubtless some of them were splendid fellows,” said Lancaster, “but we couldn’t let them turn the cradle of civilisation into a Soviet People’s Republic.” He swallowed some more wine, and grimaced. “Not without an election anyway, which they seemed to want to avoid. So, there was much fighting in the streets, embassy under siege, British peacekeeping force outnumbered, machine guns, mortars, bombs, all that kind of thing. And then in the middle of the battle who turns up but Winston Churchill? In a Royal Navy cruiser, naturally. Horribly dangerous, but he was in his element, of course. Insisted on holding a press conference while hostilities were still in progress – in the embassy garden, of all places.”

“What was wrong with the embassy garden?” asked Sophie.

“Nothing in itself, but you came into it down a set of steps, and I knew that as soon as Winnie clapped eyes on them he’d stop at the top and strike a heroic pose for the photographers. They were all waiting eagerly among the rose bushes down below. And here was the problem – the top of the steps was the one place in the garden where a sniper in one of the surrounding houses could take you out. I explained this to Winnie and he promised to keep moving, but I knew perfectly well he wouldn’t be able to resist temptation, and sure enough, as soon as he comes out of the embassy he adopts one of his bulldog stances and the flashbulbs start going off and he wouldn’t move till they’d stopped taking pictures. I was sure the end had come.”

“What did you do?” asked Sophie.

“Pushed him down the steps,” said Lancaster. “Not a very elegant solution, but sure enough, at that very moment there was a rifle crack and a handful of plaster flew out of the embassy wall right where he’d been.”

“I hope he was grateful,” said Sophie. Forrester grinned.

“Knowing his probable reaction to having his moment of glory spoiled,” said Lancaster, “I said the ambassador did it.”

Sophie grinned, there was a pause, and Forrester knew they were about to discover the reason why Lancaster had given them a lift from the airport.

“Anyway,” said the press attaché, “I wanted to fill you in on the situation before you meet up with everybody.”

“Everybody?” said Forrester. “A reception committee?”

“No, no,” said Lancaster, refilling their glasses. His and Forrester’s anyway: Sophie’s remained largely untouched. “It’s just that there happen to be a lot of people you know in town at present. Paddy Fermor, for a start.”

Patrick Leigh Fermor had been in charge of the operation in Crete in which British commandos had captured a German general and spirited him away to Egypt. It was while performing his diversionary role that Forrester had found, in the Gorge of Acharius, the cave he was coming back to excavate. He grinned as he heard Leigh Fermor’s name.

“What’s Paddy doing here? Last I heard he was in London looking for a job.”

“Well, he’s found one here, lecturing on British culture to the Greeks on behalf of the British Council.”

Forrester laughed. “I wonder what the Greeks make of that,” he said.

“They lap it up,” said Lancaster, “because all he really does is tell them war stories, and there’s nothing they like better than a war hero telling his tale. Xan Fielding’s backing him up, and we hope you will too.”

“If it helps,” said Forrester.

“Every little thing helps,” said Lancaster. “The fact is we’re in a precarious position here, and so is Greece. The fighting’s over for the time being, but it could start up at any moment. The communists are putting together an army and when the time comes, they’ll strike. Tito’s backing them from Yugoslavia.”

“So the Iron Curtain could fall over Greece too?” said Sophie.

“It could indeed,” said Lancaster, and fixed his pop-eyed gaze on Forrester. “And that’s where your old friend General Alexandros comes into it. We’re a bit worried about him.”

“He’s not a communist,” said Forrester. “I know that for a fact.”

After the Germans invaded Greece in 1941, Forrester and Aristotle Alexandros had spent weeks together, planning guerrilla operations while hiding out in a cave near Mount Olympus, and they had talked about every subject under the sun, including the Soviet Union. “He’s the most rational man I’ve ever met. One of the best read, too. He saw through Marx as a teenager.”

“But after you parted he spent the rest of the war fighting the Nazis alongside the communists,” said Lancaster, “and that makes him a suspect now as far as the Greek Army is concerned. They’re all royalists, you know.”

“But he’s the best strategist in Greece,” said Forrester. “Best tactician too. Don’t tell me the regular army’s put him on ice.”

“That’s exactly what they’ve done,” said Lancaster. “And he’s getting bored and impatient. The communists want to put him in charge of ELAS.”

“ELAS?”

“Their strike force. The so-called Greek People’s Liberation Army.”

“But surely he wouldn’t—”

“The present regime’s pretty rotten. Too many people who cosied up to the Germans. He might think he could use ELAS to take over, clean house and start again with a fresh slate.”

Forrester was silent for a moment. It was all too plausible. And if Aristotle Alexandros joined the communist army, they would win. Stalin’s campaign to control Europe would be one step closer to fulfilment.

“What do you want me to do?” he asked.

“Just talk to Alexandros, find out what you can about his thinking. Then let us know.”

“I’m very fond of him,” said Forrester. “I’m not going to sell him down the river.”

“Wouldn’t dream of asking you to, old boy,” said the attaché. “Just sound him out about whether he’s going to join ELAS, that’s all.”

“If we come across each other.”

“Oh, you’ll come across each other,” said Lancaster. “This is Greece. Besides, there’s a party tonight at the Regent-Archbishop’s, and I’ve wangled you both an invitation.”

“I had hoped to have a quiet dinner with Sophie,” said Forrester.

“I know,” said Lancaster, with patently insincere sympathy, “but I also know we can rely on you to be a good scout, old man. They speak very highly of you at the War Office, and the same can’t be said for most academics, I can tell you.”

2

HIS BEATITUDE

They walked through the warm evening air along Kifissia Street, which ran from Syntagma Square alongside the Old Royal Palace, its grounds now known as the National Garden. The topiary bushes and winding paths, Forrester knew, concealed the hastily buried bodies of the victims of the failed communist uprising in 1944, but he did not mention this to Sophie, determined not to disturb her pleasure in exchanging the cold austerity of Scandinavia for the balm of the Mediterranean.

Opposite the gardens were the pompous, wedding-cake buildings of the Egyptian Legation, the French Embassy, the Greek Foreign Office and the Ministry of War, but the edifice to which they were headed, Skaramangar House, residence of His Beatitude the Orthodox Archbishop and Regent of Greece, surpassed them all in opulent vulgarity.

“You’ll recognise it quite easily,” Lancaster had told them when he gave them directions. “It’s built in a style I call ‘Hollywood Balkan’.” Forrester placed the name then: before he became a press attaché, Osbert Lancaster had published several very funny books about, of all things, architectural history, inventing names for pompous styles and skewering them in spare, elegant cartoons. “Make sure you look out for the debased Byzantine capitals,” he had advised as they parted. Sophie looked at Forrester, puzzled.

“Debased?” she said. “Doesn’t that mean—”

“I think in this case it’s a technical term,” said Forrester. “But we are in Athens. You never can tell.” The Archbishop’s door opened and a liveried footman ushered them into a vast and crowded room. As he took their names they stopped, astonished at the spectacle before them.

Massive oak beams rested on squat pillars (topped, as promised, by the gilded shapes of the debased Byzantine capitals) from which hung baroquely ecclesiastical candelabra illuminating a sea of guests resplendent in dinner jackets, heavily braided uniforms and elegant evening gowns. Waiters glided around the room offering spanakopita, saganaki and tiropitas. A huge log roared in a fireplace so immense it reminded Forrester of Xanadu in Citizen Kane, which he and Barbara had seen the night before he parachuted into Sardinia.

Beside the fireplace, in a chair that might once have served a medieval warlord, sat Archbishop Damaskinos, robed and bearded with all the magnificence of Byzantium itself. Even seated, he looked huge: at least six foot six, seventeen stone if he was a pound, and adding to that already imposing appearance were a tall black headpiece like an upside-down top hat and a silver-knobbed staff of office, clutched in a large, meaty hand, its sausagelike fingers thick with wiry black hair. On his feet were stout black boots, which again reminded Forrester of an image from the cinema. It was a moment before he had it: the massive footwear sported by Boris Karloff as Frankenstein’s monster. Suppressing the lese-majesty of the image, and watched closely by the two splendidly uniformed Greek soldiers behind His Beatitude’s chair, in their traditional flounced skirts, pom-pommed shoes and red sock-like berets, Forrester bowed low.

“Welcome to Greece, Dr. Forrester,” said the Archbishop in thickly accented English. “May you and your countrymen help bring us the peace for which we hunger.”

“I hope very much that that is possible, Regent,” said Forrester. Damaskinos was currently regent of Greece because King George II was still in exile in London. During the war the king had been supported by the Allies as the country’s legitimate ruler, driven from power by the Nazis. But before the Axis invasion he’d been hand in glove with a semi-fascist dictator who had persecuted not just communists but anyone he considered liberal. Even the works of Plato, Thucydides and Xenophon had been banned. As a result of King George’s support for this fairly loathsome regime, it was not just the communists who never wanted to see him again.

As a result, to avoid setting off a firestorm after German troops withdrew, the Allies had persuaded King George to stay in London until a vote could be held about whether he was allowed to return, and in the meantime Archbishop Damaskinos was officially Head of State. But tonight His Beatitude did not apparently want to discuss politics; he wanted to defend his religion. Some disparaging remark about either himself or the Greek Orthodox faith, Forrester guessed, must have appeared in the British press.

“You British disapprove of Greek Christians,” said the Archbishop. “You regard us as insincere.”

“I’m not sure—” began Forrester. Sophie suppressed a smile, and Forrester realised His Beatitude had mistaken him for someone else.

“You think of us as worldly, as lacking a sincere belief in our maker,” said the Archbishop.

“No, Your Beatitude —”

“You think we are too close to the old pagan ways.”

“Why would people be thinking such things, Your Beatitude?” asked Sophie, innocently. Deflected, the Archbishop seemed to notice her for the first time, and his face suddenly lit up with mischief.

“Perhaps because it is true,” he said, instantly switching his position. “You see, dear lady, it was much easier to turn the old gods into saints than to try to abolish them.”

“So much easier,” said Sophie. “We did it in Norway with Thor and Odin. And I see you have a kouros yourself. A beautiful kouros.” The Archbishop beamed with pride and followed her gaze towards the niche in the wall at the far end of the room in which stood a four-foot-tall statue of a handsome, naked young man, his shoulders square, his head erect, his lips curved in a mysterious smile. Several people were gathered around it.

“Do you think he is the god?” asked the Archbishop. “Or an acolyte?”

“I think he is both,” said Sophie. “I think he is perhaps the god in man.” The Archbishop looked at her appreciatively.

“That is exactly what I think myself, dear lady,” he said. “You may touch him if you like.” He noted Sophie’s surprise. “As my other guests are doing.” And indeed, several members of the party were laying their palms flat on the head of the kouros, one after another, their eyes closed as if in prayer.

“They say that if you think of heaven when you touch him, God will ensure you a safe passage there. Which god and which heaven I leave for you to choose.” Abruptly, as if remembering his real purpose, he turned his attention back to Forrester. “What you British forget,” he said, “is that the Greek people love their church. They may laugh at the local priest, certainly, with his wife and children, but they look up to their bishop, and they revere their archbishop. What’s more, they expect him to play a part in the government of his country. Why should he not? Why should I not govern as well as bless?”

“Why not indeed, Your Beatitude?”

“But if the communists take over, where will the Church be then? That is my question for you, Dr. Forrester. I want you to think it over.”

“I will, Your Beatitude,” said Forrester. “I certainly will.” And the audience was complete.

“What a charming old man,” whispered Sophie as they made way for the next guests to pay their respects. Forrester grinned and gazed around the room where, lit by the flickering firelight, was gathered the whole panoply of the Greek political establishment. Red-faced Michaelis, peering at the assembly through his monocle like a benevolent London clubman; Constantine Papas, so theatrically political he looked as if he had been playing the part of a politician on some provincial stage; Admiral Plaxos, a garden gnome in naval uniform, and an assortment of individuals who represented most of the Greek political dynasties, the Venezelos, the Dragoumis, the Tsaldaris. Political power in Greece, Forrester knew, tended to be a hereditary business. Above them all towered the distinctive figure of General Aristotle Alexandros, as tall as the Archbishop but whip-thin, his eagle nose projecting over a nutcracker chin, his moustache bristling, his olive-black eyes flashing. As soon as he saw Forrester he abandoned the politicians, strode across the room and embraced him.

“Duncan,” he said. “Duncan the digger.”

“I never got to dig when I was with you, Ari,” said Forrester. “Too many people shooting at us.”

“And missing us,” said the General. “Because we were too quick for them. Who is this beautiful woman?”

Forrester introduced Sophie, and was amused to see that there was an immediate glint in the General’s eye.

“I am at your service, my lady,” said Alexandros, and gestured to the assembled company. “Feast your eyes on our film stars.”

“Film stars?” said Sophie, surprised, as Alexandros had clearly intended.

“The Greeks think of their politicians as the rest of the world thinks of film stars,” he said. “Or the English think of horses.”

“From which I infer that Greeks have a serious interest in politics?” said Sophie, smiling.

“Oh, yes,” said the General. “Very serious. The poorest cigarette seller has an opinion on who is about to be traded from his team, who is about to be given a starring role in the next production, who is about to be put out to pasture.”

“Which generals are going to stage a coup,” said Forrester, feeling he ought to say something to repay Lancaster for the ride from the airport.

“Oh, coups,” said Alexandros. “They are so old school. Just exchanging one team for another, with a few shots fired at half-time. I think something larger is in the air these days.”

“What’s that?” said Forrester, but before Alexandros could reply an arm was thrown around his shoulder and gripped him tight.

“What are you doing out in the sunlight, you old mole?” and Forrester turned to see the beaming face of David Venables, last glimpsed boarding an armoured ferry to cross the Channel just after D-Day, following the invading army with a microphone and a BBC Outside Broadcast van. Despite the formality of the occasion he was still carrying over his shoulder the canvas bag in which Forrester knew he kept whichever manuscript he was working on at present, which would be further encased in an odiferous oilskin pouch whose distinctive scent was discernible even here in this maelstrom of hair pomades and perfumes.

Forrester had met Venables under a table in a pub in Soho when they were caught in a raid at the height of the blitz, and been pleasantly carried away on the tide of acerbic wit that flowed out of the man as the floor shuddered with each falling bomb. Venables had begun his working life as a naturalist, and looked at the human race as if they were so many ants milling about an anthill, but he had wisely disguised the cynicism under a coating of cosy wit for his weekly nature broadcasts on the BBC Home Service. “Our Friend the Vole” and “Otters I have Known” were among his most popular broadcasts. When he was in company he felt he could trust, however, he would frequently compare the passions and rituals of the human race to those of the orangutan, the parrotfish and even the amoeba, usually to the disadvantage of Homo sapiens.

“I’m digging up Crete,” said Forrester, noting out of the corner of his eye that Sophie, with some effort, was in the process of gently disengaging herself from Alexandros. “And you? What poor dumb beasts are you gunning for now?”

“Greeks,” said Venables. “Keith and I have come to write our Greek book. Or rather,” he added, tapping his canvas bag, “my Greek book – Keith will merely draw the pictures.”

“Which will be the only reason anybody ever opens it,” said the stocky young man beside him. “And once they close the book, my pictures will be all they’ll ever remember.” He shook hands with Forrester and bowed to Sophie as she joined them.

“Keith Beamish,” he said. “Be like Dad – Keep Mum.”

Sophie, joining them, looked puzzled.

“Wartime poster,” said Venables. “Advising people to keep secrets. Keith did the picture, and it went to his head.”

“Always made me laugh,” said Forrester. He turned to Sophie. “‘Keep Mum’ is colloquial English for not saying anything. It’s a pun.”

“Is it a good one?” said Sophie.

“Not very,” said Beamish, “but my picture was terrific. The lady in it, draped over a couch, was very… attractive. Very like you, in fact. What brings you here?”

If Forrester had been the jealous type, he might have resented both Beamish’s instant familiarity and the fact that Sophie seemed to reciprocate it.

“I’ve come to make sandwiches for my archaeologist,” she said, smiling, “while he digs up long-lost Minoans.”

“Perhaps I’ll tag along and draw you,” said Beamish. “It’ll be a lot more interesting than anything Venables asks me to do.”

“What’s this I hear about a bloody book?” said a loud voice behind Forrester, and he turned to see the lanky figure of Patrick Leigh Fermor. “Far too many people writing books about Greece, Venables,” said Leigh Fermor. “You have to get in line. You’re not writing one too, are you, Forrester?”

“Just a paper,” said Forrester. “About the dig. If I find anything.”

Leigh Fermor pointed an accusing finger at him. “I’ve a strong suspicion you were off looking for Minoan ruins when you were supposed to be helping me harass Germans,” he said.

“Well, harassing Germans was all very well up to a point,” said Forrester. “Looking for ancient Cretans was much more interesting.” Leigh Fermor grinned and punched him in the arm.

“Good to see you again, Duncan,” he said. “Glad you made it through.” There was real affection in his voice, and Forrester remembered again why he had been prepared to follow this man through hell and back during those desperate days in Crete.

“You too, Paddy,” he said. “I gather your lectures are bringing down the house all over the Aegean.”

Leigh Fermor leant closer. “Let me tell you a secret,” he said. “Spinning yarns about the war is considerably more fun than fighting it.”

Keith Beamish said something that provoked general laughter, particularly, Forrester noted, from Sophie, and Leigh Fermor used its cover to draw Forrester aside. As he did so he saw David Venables drawing Alexandros in the direction of the kouros.

“Ever heard of a chap called Cornelius Brandt?” said Leigh Fermor. “Dutchman. Medium height. Curly hair. He has a rather bizarre face.”

“Doesn’t ring any bells,” said Forrester. “What do you mean about his face? What’s wrong with it?”

“Well, half of it is covered by a tin mask,” said Leigh Fermor. “On which he’s painted half a mouth and an eye. Not very well, I’m sorry to say.”

“And you mention this because…?”

“He’s been looking for you.”

“What?”

“Hovering around the fringes of some of my lectures. Asking if you were one of the party.”

“Did he say why?”

“No. But I got the impression he meant you no good. I was wondering if he had a score to settle.”

“I don’t recall particularly doing any Dutchmen down during the late hostilities. They were on our side, if I recall rightly.”

“What about during one of your escapes?” Forrester knew what Leigh Fermor meant. He had indeed sheltered with several Dutch families when he had been on the run in Holland, and though as far as he knew none of them had been betrayed, the fact was that some of those who had helped British servicemen hide from the Gestapo had subsequently been turned in by their compatriots. Or by the carelessness of those they had aided.

“I don’t think so,” said Forrester. “I was never recaptured and I never told anybody who’d helped me get out.”

“Bit of a puzzle, then, isn’t it?” said Leigh Fermor.

“It is,” said Forrester. “But thanks for the tip.”

“My dear chap,” said Leigh Fermor. “I want you to stay in one piece for as long as possible. I can’t wait to see what you dig up in our old stamping ground.”

“To chamógeló tou eínai gia mena mia apólafsi kai ta matia tou—” said a deep voice from across the room. As Sophie turned her head towards the speaker, Forrester whispered in her ear.

“Jason Michaelaides,” he said. “The poet.” The Greek had displaced Venables and Alexandros from beside the kouros so he could command the room.

“What is he saying?” asked Sophie.

“His smile delights me,” said Forrester, “I think he’s speaking of the kouros – and his eyes—”

“—Lámpoun me mia chará pou den tin kséroume apo tote pou oi ánthropoi ítan paichnídia neogennithénton theón.”

“Shine with a joy we have not known since men were playthings of fresh-minted gods.”

As Michaelaides declaimed the last line his hand rested lovingly on the head of the kouros and it seemed for a moment as though the stone figure’s lips curled in pleasure.

“Fresh-minted gods,” said Sophie, savouring the words. She looked across at the long, mournful face of the poet as Alexandros led the applause that rang around the room. “That’s wonderful,” said Sophie. “Do you know him too?”

“A little,” said Forrester. “Met him in Cairo. Melancholy, as if he’s always on the point of saying goodbye to life. I’ll introduce you if you like.” But as they moved across the room, they were waylaid by a plump man in a dinner jacket decorated with an impressive row of colourful medals. Forrester recognised him as Prince Constantine Atreides, one of the leading Greek royalists. His thick black hair, usually hidden beneath a panama hat, was plastered firmly in place with copious quantities of scented pomade.

“Captain Forrester,” he said. “How splendid to see you back in Greece again.”

“Your Highness,” returned Forrester. “It seems a long time since the Shepheard Hotel.”

“To say nothing of the Ritz,” replied Atreides. “And their excellent cucumber sandwiches.” Atreides had fled Greece with King George when the Germans arrived, and had spent a considerable amount of time in Cairo and London with the government in exile, polishing up his anti-fascist credentials without having to fight any actual fascists. He was lazy, passionate and intensely romantic. Despite himself, Forrester had always liked him. There was something distinctly Ruritanian about him, as if he came out of a novel by Anthony Hope.

“May I introduce the Grevinne Sophie Arnfeldt-Laurvig, Countess of Bjornsfjord?”

Atreides clicked his heels and made a bow that would not have looked out of place in a production of The Prisoner of Zenda.

“Enchanted,” he said. “I think in fact I met your husband the count once at Gstaad.”

“That sounds highly probable,” said Sophie lightly, and there was no hint in her expression of the truth about Ernst Arnfeldt-Laurvig, a drunkard and a vain, foolish gambler who had dabbled in black magic with the notorious occultist Aleister Crowley and nearly brought the estate to ruin in the 1930s. He had been killed when the Germans invaded Norway in 1940.

“I suppose you are here to prepare for the return of your king,” said Sophie politely.

Atreides looked comically rueful.

“He cannot come back without a referendum,” he said. “Who would have thought the Royal House of Greece would need to subject itself to a referendum before regaining its rightful position?”

“Will you win?” asked Forrester.

“Of course,” said the prince. “The Greeks love their monarch. But the communists will try to stop the referendum happening.”

“How?”

“I think they will renew the civil war,” said Atreides.

“And if they do, do you think they’ll win?”

Atreides glanced over towards General Alexandros, still holding court on the far side of the room. “That depends who they have on their side,” he said, darkly.

As if sensing the prince’s glance, Alexandros turned towards them – and Forrester saw his face grow pale. For a moment he was at a loss: the General’s look could not be directed at him, and Constantine Atreides had never made anyone nervous in his life. Then he realised Alexandros was looking beyond them, towards the door, where two beautiful women were entering. The shorter of the two was dark, and exuded an animal energy, her dark eyes gleaming as they flickered around the room.

“Helena Spetsos,” whispered Constantine. “She fought alongside Alexandros during the war.”

“I’ve met her,” said Forrester. “She’s a formidable woman.”

Helena was surrendering her evening wrap to a footman as though conferring a blessing.

“And the blonde girl?” said Sophie. Helena’s taller, younger companion looked willowy by comparison, her fair hair braided in thick plaits, reminding Forrester of a statue of the goddess Diana.

“Ariadne Patrou,” said Atreides. “Helena’s muse. You will see Helena’s portraits of her in the National Gallery one day. When the king reopens it.”

Suddenly a man in a colonel’s uniform was embracing the two women, his voice booming through the room.

“The two muses!” he said. “Come down from Olympus to grace us with their presence.”

“Giorgios,” said Helena Spetsos, firmly trying to disengage herself from the colonel’s arms. “Anyone would think you were asking us to dance.”

“I am not worthy to dance with two such beauties,” said the colonel. “And besides, I prefer to dance alone.”

After Forrester had left mainland Greece, Giorgios Stephanides had become Alexandros’s top lieutenant, and after the Thebes massacre, his second in command. But long before he had joined the resistance, Stephanides had established himself as one of Greece’s leading novelists, most famous for Patros, the elemental peasant who, when troubles threatened to overwhelm him, danced alone on the beach to the sound of the bouzouki.

“Would you like me to show you?” the colonel asked.

“Not yet, Giorgi,” said Helena. “Perhaps when I have paid my respects to His Beatitude and spoken to Ari.”

“Alas, dear lady,” said Colonel Stephanides, “you have just missed the General.”

Helena glanced sharply in the direction of Alexandros’s admiring circle and Forrester, following her look, realised Alexandros had vanished. Suddenly Helena’s eyes flashed with anger and she leant close to Giorgios.

“Doing your master’s bidding again, Giorgi?” she hissed, for it was now clear Stephanides’s job had been to delay them until Alexandros could leave the room.