6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

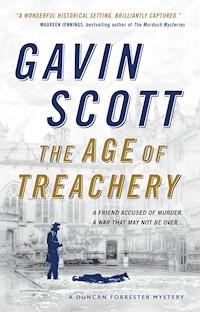

Ex-Special Operations Executive agent Duncan Forrester has returned from the war and is back at his Oxford college as a junior Ancient History Fellow. But his peace is shattered when a much-disliked Fellow is found murdered in the quad. Forrester is not convinced of the principal suspect's guilt and, on the hunt for the true killer, he finds himself plunged into a mystery involving lost Viking sagas, Satanic rituals and wartime espionage.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 380

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Gavin Scott

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1. Three Lumps of Coal

2. Ragnarök

3. Operation Torch

4. Meeting in a Ruined City

5. Fencing Match

6. Discussion by an Unlit Fire

7. A Plan of Campaign

8. The Master’s Port

9. Conversation in a Waiting Room

10. X-Ray Crystallography

11. Drama King

12. Dark Water

13. The Big Board

14. Heavy Water

15. A Walk in the Lodge

16. The Philosopher of Berlin

17. The Blue Cat

18. The Bouncing Czech

19. Up the Down Staircase

20. Northern Lights

21. Night in the Forest

22. Prince of Denmark

23. Conversation with a Wife

24. The Enthusiasm of Kenneth Harrison

25. The Secrets of David Lyall

26. Snowball on a Grey Afternoon

27. Questions Raised by a Suicide

28. Lunch at the Café Royale

29. A Message from Hamlet’s Castle

30. Preparations

31. The Secret of the Book

32. The Gorge of Acharius

About the Author

Coming Soon from Titan Books

ALSO BY GAVIN SCOTT AND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

The Age of Olympus (April 2017)

The Age of Exodus (April 2018)

The Age of TreacheryPrint edition ISBN: 9781783297801E-book edition ISBN: 9781783297818

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: April 201610 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2016 Gavin Scott

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

TO NICOLA, REBECCA, LAURA AND CHLOE

1

THREE LUMPS OF COAL

SUNDAY, 13 JANUARY 1946

The snow had been falling since noon, and Duncan Forrester brushed urgently at the stone bench to clear a space to sit down before the vertigo overcame him. The spinning sensation continued for a moment, but then silence began to seep in and he felt his heart slow.

The buildings around St. Mary the Virgin were mostly Baroque, and the snow was piling deep on their window ledges. The church and its adjoining houses shut the churchyard off from the bustle of the city, and Forrester felt as if he was in a tiny clearing in a dense, silent wood.

There were few cars in Oxford just after the war, and little fuel for them anyway, so what noise there was mostly came from footsteps in the street beyond, and even they were muffled. As the snow came down and the light leaked out of the afternoon sky, he closed his eyes and waited for the demons to slip away into the gloom.

He could not banish them; he’d tried that. He could only let the images rise to the surface unopposed. He felt the familiar wave of nausea but he forced himself to ride it, reminding himself this was not reality: it would fade.

He felt again the peculiar gliding sensation as the knife passed through the cartilage of the sentry’s throat; he smelt the youth’s skin as he gripped him, and then the warmth of the blood as it poured over his fingers and the body slid down to his feet, looking up at him with mildly reproachful eyes. Forrester guessed he was about seventeen. As the sentry died Forrester could see, through the archway leading to the castle courtyard, SS guards taking the prisoners into the basement.

There were many such images. He let them unreel at their own speed.

He saw Barbara again too, that last time at Waterloo Station, and the look in her eyes that made him think of Arctic winds blowing over the ice.

He did not see the man watching him from the tall, unlit window of the vicarage, but the watcher noted the set of Forrester’s shoulders and the tilt of his head, and long experience allowed him to infer the nature of the man’s thoughts with some accuracy.

For a long time, both of them were motionless, separated by no more than fifty yards of snow and lichened stone.

Suddenly, from the archway that led to the street, Forrester heard the word “vintersolstånd” followed by laughter, and then a brief babble of Swedish before the speakers passed on. There were students from all over Europe in Oxford now, a flood pent up by the war, released by the peace. They were not the high young voices of his own university years, but deeper, more mature. Many of the British undergraduates were ex-servicemen, their education postponed by the conflict. They too poured in, thirsty for knowledge.

Duncan Forrester had graduated before the war began, and now, just months after the German surrender, he was back at Barnard College, Junior Research Fellow in Archaeology. But though he was still in his twenties, he felt bone tired, as if he were an old man.

He held out his hand and watched the snowflakes settle on it. As the heat of his body turned them to water, the drops rolled into his palm, forming a tiny pool. By the time he realised his hand was numb with cold he was calm again.

He paused a moment, savouring the calm, and went through the ritual. He was alive; he was in one piece; the war was over; he was back in Oxford; he was free to pursue his research. Images of Barbara came and went, but all they evoked now was remembered pain – and deep behind that, remembered joy, like a distant Eden.

The man in the window watched as Forrester rose to his feet, shook the snow off him, tightened the belt of his British Warm overcoat, headed back through the archway into the street, and disappeared. Only then did the watcher switch on the light inside the room, letting it spill over the empty churchyard like liquid gold. Moments later he closed the curtains, plunging the enclosure back into the afternoon half-light.

Among the crowds in the street, Forrester felt almost normal again, just one of the many going to the shops on their way home from work. Not that there was much to buy, for this was austerity Britain, a victorious nation ruined by the struggle for victory. CADBURY’S MILK CHOCOLATE IS THE BEST proclaimed a poster showing the familiar purple and gold wrapper so evocative of pre-war pleasures. Then in smaller letters below: “Unfortunately we are only allowed enough milk to make extremely small quantities of our famous product, so if you are lucky enough to get some, do save it for the children.”

But Forrester, who had not seen a piece of chocolate for at least a year, knew no children to save it for. He glanced into the brightly lit interior of Woolworths, an Aladdin’s cave of gaudy trinkets before the war, now full of half-empty glass counter-trays scattered with a sparse collection of wooden pegs, darning needles and penny notebooks. Outside a grocery shop a notice announced a limited supply of dried egg powder and a queue was already forming. For most of the war people had had to rely on the hated dried eggs instead of the real thing. Cakes made with egg powder had the texture of old cement; when mixed with water and fried, the powder turned into luridly yellow leather pancakes. And then, with victory, not only did fresh eggs not reappear but even dried egg powder had vanished; unavailable until Britain could borrow more money from the Americans. So women were now lining up patiently with their string bags, shivering in the cold, desperate for a product they had despised for five years.

And this was what happened when you won.

A woman darted out of the queue – which closed up immediately behind her – and ran towards Forrester. Her name was Margaret Clark, she worked at the Bodleian Library, and in his eyes she was the most desirable woman in Oxford; a thought he tried to suppress because she was also the wife of his closest friend. And though her eyes were bright with affection, he knew the affection wasn’t for him – her gaze was fixed on someone on the far side of the road.

As a result of which, as she stepped off the kerb it was into the path of an oncoming bus.

Forrester shouted a useless warning as the bus swerved and sent up a spray of grey slush. The slush momentarily blinded him and when he had wiped it from his eyes the bus was gone and so was she. But to his astonishment no blood stained the snow; no crushed body lay in the road. The bus had missed her. He peered at the crowd across the road but she had vanished as if she had never been.

“Got something for you, Dr. Forrester,” said Harrison, materialising at his elbow, a pipe clamped between his teeth. Forrester forced himself to concentrate.

“Delian League?”

“Oh, that,” said the student, dismissively. “No, much better.” Ken Harrison was a cheerful, stocky former Signals Corps lieutenant of twenty-four, who had been trying furiously to get a faulty field radio to work when he was captured at Arnhem and taken as a POW to Germany, an experience which seemed to have left no mark at all on his sunny disposition. Forrester was tutoring him in Greek history.

“Better than one of your essays?” said Forrester.

“That wouldn’t be hard,” said Harrison equably. Both he and Forrester were well aware that Harrison’s disquisitions on the Golden Age scaled no heights of brilliance, but Harrison was as unperturbed about that as he seemed to be about all the vicissitudes life threw his way.

They passed under the worn stone archway of Barnard College, past the porter’s cubbyhole with its tabby cat and ticking clock and pigeonholes full of messages, and entered the first quadrangle. The snow lay thick on the famous lawn and the Great Hall and the Lady Tower, festooned with scaffolding where builders, under the impatient supervision of Deputy Bursar Alan Norton, were slowly – very slowly – repairing the damage done when it had been an air raid warden’s observation post during the war. Undergraduates and fellows hurried back to their rooms along the cloisters as the light dimmed and the afternoon turned to evening.

Forrester and Harrison scraped the snow off their feet and clumped up the narrow wooden stairs to Forrester’s rooms. The air struck cold as Forrester knelt down by the fireplace and fiddled with his matches; Harrison reached into the canvas army satchel he used as a book bag, pulled out something wrapped in newspaper and gave it to his tutor. Forrester read the headline as he unwrapped the paper.

ALBANIA GOES COMMUNIST. WHO’S NEXT?

Inside were three lumps of coal.

“Where did you get these?” Forrester said, and immediately added, “Actually, better not tell me,” and put the lumps on the fire. “But it’s very kind of you. Thanks.”

Coal was another item Forrester had not seen enough of since he came back from the war. But Harrison had a knack for getting his hands on these things. Perhaps that was what he had learnt in the German camps.

They both kept their coats on in the frigid air as the kindling flamed up and Harrison took out his essay and began to read. By the time the flames were sending out any heat both men were far away, on the plains of Athens with the sun glinting off the marble of the Acropolis – and Forrester had, for the moment, forgotten all about Margaret Clark.

Outside, around the college, one window after another began to glow with yellow light, like the opening doors of an Advent calendar.

* * *

The fire was dying down by the time Harrison left, and Forrester took a shovel full of ashes and banked it down to preserve the coal. The warmth in the room would last until it was time to go to the Great Hall for the evening meal. Then he took Sir Arthur Evans’ photographs from his desk drawer and began to look at them again. They were very bad photographs; or rather, infuriatingly imperfect for his purposes, showing small rectangles of clay, thickly inscribed with symbols and stick figures. Here and there he could make out a symbol that might be a horse’s head, and another which looked like a double-bladed axe, but most were indecipherable. The script was known as “Linear B” and the tablets on which it was inscribed had been baked in the heat of the fire that had destroyed the palace of Knossos in Crete a thousand years before Athens rose to glory. No-one had been able to decipher the tablets since Evans discovered them, and Forrester suspected that some of Sir Arthur’s guesses had put his fellow archaeologists on the wrong track. What if, for example, the old man had been wrong about the significance of the symbol that looked like a double-bladed axe? What if it did not in fact signify a religious ritual, but was actually a phonetic indicator? He turned to the drawings Evans had made of other inscriptions, and wondered how accurate they really were.

“You’re busy,” said a voice. Forrester looked up to see Gordon Clark looking round his door. For a moment he was tempted to tell the Senior Tutor “I am a bit busy, actually, old chap,” and turn back to the tablets, but when he saw Clark’s white, strained face he hadn’t the heart.

“Absolutely not,” he said. “Come in and have some sherry.”

“Thank you,” said Clark, and closed the door. He entered the room nervously, glancing into the shadows as though expecting a hidden observer.

Forrester, pouring the sherry, realised the bottle was almost empty. He thought of dividing the liquid between both glasses and decided against it. With his back to Clark he filled his own glass with cold tea before he handed the full one to his friend.

“Your health,” he said, and Clark nodded and sank back into a chair on one side of the fire. Forrester reached in with the poker and stirred it into life.

“Any progress?” said Clark, nodding towards the photographs spread out on Forrester’s desk.

“I’m not at the progress stage yet,” said Forrester. “I have to dig myself in much deeper before I can start digging my way out.” He sipped his glass of cold tea with every appearance of appreciation. “I saw Margaret in Broad Street this afternoon. I think she’d just given up queuing for powdered eggs.”

He waited for Clark to tell him that it was he, her husband, she’d been running across the road to see, but the Senior Tutor just nodded and looked into the fire. Finally he said, “Have you ever understood them, Forrester?” When Forrester did not reply, Clark said, “Women, I mean.”

“Good Lord, no,” said Forrester. It was not what he felt, it was not what he believed; but it was what Clark needed to hear. “But surely a married man has a better chance than most?”

“You’d think so, wouldn’t you?” Clark sipped the sherry, but Forrester knew he could have given him the cold tea and the Senior Tutor wouldn’t have noticed. Suddenly his friend looked up, his eyes hot with pain. “She used to love me, you know.”

“I’m sure she still does,” said Forrester, with a strange sinking feeling in his stomach.

“No,” said Clark. “She’s found someone else.”

Again, Forrester decided silence was the best response. His own feelings for Margaret Clark made it almost impossible to make the right comforting remarks.

“And you know the worst part of it?” said Clark. “I feel… slighted—”

“Well, of course—”

“—by the man she’s chosen.” Forrester held his breath. “Do you know who it is?” Forrester shook his head. “David bloody Lyall.”

“That’s ridiculous,” said Forrester, automatically, quick to cover his own swift stab of jealousy, but in truth he was not in the least surprised at Margaret Clark’s choice. David Lyall was handsome, self-confident and stylish. He was ambitious and successful; he’d leapt ahead of several other abler candidates for the Priestley Latin Fellowship and was a serious contender for the Rotherfield Lectureship, but Forrester understood why Clark felt slighted: Lyall was also shallow, meretricious and glib; a showy scholar without real insight. But scholarship, of course, was not what Margaret had been looking for.

“I always used to look down on Italians, you know,” said Clark. “All that passion and jealousy. It seemed so self-indulgent. But I tell you, Forrester, I could cheerfully strangle that little swine.”

“Do him good,” said Forrester, and despite himself, Clark laughed.

“Unfortunately they didn’t teach us much about unarmed combat at Bletchley,” said Clark. Forrester nodded. He knew enough about what had gone on at Bletchley to understand the intense intellectual strain Clark had been under for the last four years, his nerves strung out like a taut wire.

“As someone who was taught unarmed combat,” said Forrester, “I can tell you I don’t recommend its use in polite society.”

“Not even in special circumstances?” asked Clark.

“This Lyall thing’s an infatuation,” said Forrester. “It’ll pass.”

“How do you know?”

“Because Lyall is a complete second-rater; you are a man of real worth and Margaret is an intelligent woman,” replied Forrester decisively. “She’ll see through him before long.”

“And I should just hang about until she does?”

“I don’t know,” said Forrester. “I can’t advise you there. All I’m saying is don’t do anything precipitate.”

“Like sticking a knife in his heart?”

“I think that would qualify as precipitate.”

“I’ve got to sit at High Table with the swine.”

“Ignore him. Sit at the other end. If you catch his eye regard him with cold contempt.”

Clark grinned ruefully. “Cold contempt, eh?”

“Buckets of it. I’ll do the same. He’ll have cold contempt everywhere he turns.”

Clark finished his glass and stood up. “Thank you, old chap,” he said. “I had to tell somebody; I was going out of my bloody head.”

Forrester stood up too. A bell began to toll. “Shall we go down?”

Clark hitched his gown around him. “Why not?” he said. “I’ve worked up quite an appetite.”

2

RAGNARÖK

In the event, inevitably, the Master kept them hanging about in the Fellows’ Chamber before they could go through to High Table. A giant with a face like a Viking axe was standing in the centre of the room as they entered, his sherry glass like a thimble in his massive fingers, the timbre of his thickly accented Norwegian voice so deep Forrester could swear his glass was ringing as he spoke.

“In the year of Our Lord, 998,” the Norwegian was booming, “Sigrid the Strong-Minded was wooed by both Prince Weswolf and Harald Skull-Splitter, neither of whom pleased her. She took them to a beer hall, got them drunk and as they lay sleeping, set fire to the place, burning them both to death. After this only the boldest suitors approached her, which is what I think she intended.”

There was a murmur of appreciative laughter, led by Professor Michael Winters. The Master of Barnard College was a plump man with a fringe of white hair around his egg-shaped cranium and a face which looked slightly too small for the size of his head, like a child’s sketch painted on a balloon. He turned to Clark and Forrester, gesturing at the Norwegian. “This is Professor Arne Haraldson, from the University of Oslo,” he said. “My star turn at the reading tonight. I trust you’re coming?”

Forrester sighed inwardly. Winters’ evenings of readings from the Icelandic epics were, for those unenthused by Dark Ages poetry, famously painful. But he liked the Master too much to let him down. “Of course, Master,” he said. Clark had managed to edge away before he had to respond; Forrester knew that in Gordon’s present state of mind an evening listening to tales of Vikings hacking one another to pieces was more than he could bear.

“What are your views on the links between Norse mythology and Nazism, Professor Haraldson?” Forrester turned and saw that the speaker was David Lyall. The question was typical of the man: designed largely to draw attention to the questioner.

Forrester saw a curious expression on Haraldson’s face as he turned to Lyall – a flash of surprise that morphed swiftly into fury, as though someone he trusted was reneging, quite shamelessly, on a deal. For a moment Forrester expected the big man to reach out and grasp Lyall by the throat but instead, after a beat, he drew in a deep breath and smiled.

“There are no true links between Nazi fantasy and Norse mythology,” he said at last, “whatever Hitler might have imagined.”

“Adolf was pretty much convinced otherwise, though, wasn’t he?” Lyall persisted. “He had that mystic experience in a wood during the Great War, didn’t he?” Lyall had an athlete’s build, with a fine head and bright blue eyes. Forrester could see why Margaret Clark had been attracted to him.

“What ‘mystic experience’?” said someone. The smile remained on Haraldson’s face, but it was fixed now, his eyes hard.

“The future Führer described the scene very vividly,” Lyall went on, apparently oblivious to Haraldson’s anger. “It was on a hill above his line of trenches: a place he called Wotan’s Glade. Apparently it was very cold, snow everywhere, and he used his bayonet to carve certain runes on a fallen log. He claimed it was there that Odin revealed his destiny to him.”

“The future Führer was deluded,” said Haraldson, “as the events of April last year demonstrated.” It had been in the previous April, of course, that the Führer had shot himself in his Berlin bunker, and the Thousand Year Reich had come to a premature end.

“And those of us who study literature would very much prefer that those delusions should be forgotten,” said Roland Bitteridge. His voice was high-pitched and unattractive, like a triangle being played after a great bell had been struck. “These fantasies have nothing to do with serious study, Dr. Lyall, as you must know.”

“I couldn’t say,” replied Lyall. “It’s not my field.” He was speaking to Bitteridge, but Forrester felt, for some reason, that the remarks were still addressed to Haraldson. The Master intervened swiftly to set the conversation in another direction.

“I have one disappointment for you this evening, I’m afraid.” He paused and cleared his throat apologetically. “Professor Tolkien isn’t coming.” There were polite murmurs of regret from around the room. Tolkien had begun the tradition of readings from the sagas at Oxford, forming with C.S. Lewis a group known as the Coalbiters, after an Icelandic phrase referring to those who sat so close to the blazing hearth on winter evenings that they seemed to be eating the fire.

“He was supposed to be here,” the Master went on, “but he’s moving house and everything seems to have got into a tremendous muddle. Some manuscript he’s mislaid.”

“Another Hobbit?” Tolkien’s children’s book, written in the thirties, had just been republished and Forrester had seen its distinctive green and white dust jacket in Blackwell’s bookshop that afternoon.

“Oh, something much bigger,” said Bitteridge. “He’s been trying to finish it for years – but you know what he’s like. Jack Lewis will pip him at the post if he’s not careful.”

“I don’t follow you.”

“Jack’s writing his own fairy stories. Dwarves and nymphs and fauns and that kind of thing. I suspect Tollers thinks it’s pretty meretricious stuff, and it probably is.”

“They’re both looting the sagas, aren’t they?” said Forrester.

“Of course,” said Bitteridge. “But C.S. is writing his stuff on behalf of the Christians, and Tolkien doesn’t approve of that. Can’t say I blame him.”

“At any rate,” said a voice somewhere behind them, “it’s better than writing on behalf of the Devil, isn’t it?” Forrester turned to see who had spoken, but the face was lost in the crowd.

* * *

At last they went through to the Hall, built when Henry VII was on the throne, and were seated at High Table, looking down at the undergraduates watching impatiently as the food approached. The silverware sparkled in the light of the candles and the shadows they cast flickered against the great hammer beams supporting the roof. Forrester hoped the sheer familiarity of the scene gave Gordon Clark the comfort it always gave him.

Bitteridge was placed next to Haraldson, and they were deep in conversation, Forrester noted, with the Norwegian nodding vigorously as he shovelled food into his mouth. He would have looked even more at home, Forrester thought, if he’d been chewing on a leg of wild boar. Bitteridge, by contrast, merely ferried fastidiously tiny forkfuls from the plate to his thin lips.

He looked down the table towards Gordon Clark and cursed under his breath as he saw that the Senior Tutor was sitting opposite David Lyall. But of course as no-one knew about Lyall’s affair with Clark’s wife, no-one had thought to separate them. Forrester forced himself to listen to the languid Foreign Office man seated beside him. His name was Charles Calthrop, he had attended the college in the early thirties, been recruited into the Foreign Office when it was dominated by the appeasers and was now speaking airily of the growing Soviet domination of Eastern Europe. “Oh yes,” he was saying. “Albania declared a People’s Republic two days ago. It’ll be the same in Hungary within the month. And then we should all look out for the Russian army marching towards us with snow on their boots.”

“Is that a serious possibility?” asked Forrester.

“Of course it is,” said Calthrop. “If they can’t get the local communist parties to do it for them. Italy could go red any day. Look at what’s happening in Greece. The fact is, if we want to keep the Russians from taking over, the Americans are our only hope.”

“I don’t see why you’re afraid of Russia,” said the man on the opposite side of the table. “Stalin saved this country during the war.” The remark came from Alan Norton, X-ray crystallographer and deputy bursar, responsible for repairs to damage done to the college fabric during the late hostilities. “Hitler would be living in Buckingham Palace today if it hadn’t been for the Soviets.”

Calthrop favoured him with a long, amused glance.

“I can’t say anything about hypothetical accommodation arrangements for the Führer,” he said, “but I have to tell you that Stalin is a truly bad man.”

“And you make that statement on what basis?” asked Norton.

“Meeting him,” said Calthrop, mildly. “I was close enough to him at Yalta to be aware of an aura of… how shall I put this? An aura of pure evil.”

Before Norton could rebut this shameless piece of one-upmanship, the balding, sandy-haired German beside him spoke up. “My own view is that the Russians have swallowed as much of Europe as their Slavic stomachs can digest.”

The German’s name was Peter Dorfmann, and it was rumoured that he was being groomed for power when the occupying forces set up the new, democratic Germany. Forrester wasn’t clear exactly how he’d managed to remain a respected academic in the Third Reich without either joining the party or falling foul of it, but apparently he had. “Besides,” said Dorfmann, “I do not believe the Russians have any desire to fight the Americans.”

“The Americans,” said Norton contemptuously, “are the occupying power in Europe these days. They’ve turned us into one big aircraft carrier.”

“You’re not suggesting we could have won the war without them, are you?” remarked Lyall from across the table. “I mean, were you out in the streets on D-Day saying ‘Yanks go home’?”

Forrester saw Clark glance up as Lyall spoke and shot him a look that warned him to stay out of this dispute, but Norton was in full spate. “The Americans were pursuing their own interests when they finally deigned to come into the war, and that’s what they’ll go on doing,” he said. “Anyone who thinks otherwise is naive.”

“Naivety,” said Lyall, as if savouring the word. “It’s a wonderful word for clubbing your opponents over the head, Alan. Much used in Party circles, I believe?”

“I’m not a member of the party,” snapped Norton, “as you very well know.”

“You might give that impression, though, to our guests,” said Lyall, like a picador enraging a bull. There had been plenty of speculation that Norton was a communist fellow traveller.

At which point Gordon Clark could no longer resist. “I’m sure our guests don’t expect to hear fellows quizzing each other about their political affiliations, Lyall,” he said. “After all, this is a bastion of learning, not an inquisitorial chamber.” It was a splendid stroke: Clark had neatly defined Lyall’s baiting of Norton as boorish and crass. For a moment the younger man was at a loss. Then he smiled warmly at Clark.

“I’m so sorry, Gordon,” he said. “I’d forgotten how delicate your sensibilities are.” He looked around the table. “Dr. Clark is Senior Tutor,” he said as if in explanation. “I think dealing with undergraduates takes a great toll on his nervous system.” He looked again at Clark with apparent solicitude. “I promise to keep the conversation innocuous from now on,” he said, and turned back to Dorfmann.

Clark was silent for a moment; Forrester could see that his friend was boiling with fury at Lyall’s revenge, which, true to form, neatly combined truth with slander. Clark was indeed highly strung not because of the demands of being Senior Tutor but due to the toll his war work had taken on him. It was impossible to establish the distinction, but Forrester knew Clark was too angry to let the gibe pass.

“It’s not blandness one seeks at High Table, Lyall,” he said. “It’s – how shall I put it? – incisiveness. Something I have to constantly remind my undergraduates: there’s no point in speaking for the sake of being heard, however amusing one finds the sound of one’s own voice.”

The Master intervened before Lyall could hit back. “I’d be very grateful for your opinion of the claret, Roland,” he said to Bitteridge. “We’ve just opened a new bin and I’m wondering if we left it too long.” Winters turned to ensure everyone else was part of this new conversation. “Roland is not just a great English scholar,” he said, “but he also has one of the great noses.”

There was general laughter and Bitteridge looked enormously pleased at the compliment. “Well,” he said, considering the claret judiciously, “I think, Master, you are to be congratulated.”

And the conversation moved onto safer ground. Forrester felt himself start to breathe again. He’d been afraid, for a moment, that his friend would throw himself across the table and knock Lyall backwards out of his chair. God knows, he’d been tempted to do it himself, and it wasn’t his wife that Lyall was making love to.

* * *

By the time those who had agreed to attend the Icelandic reading crunched through the snow across the inner quadrangle to the Master’s Lodge, clouds were scudding across the moon. As well as Haraldson, Calthrop and Dorfmann there was a mix of Barnard Fellows, and wives and dons from other colleges. David Lyall, Forrester noted with relief, had decided to absent himself.

Inside the Lodge, a minstrels’ gallery ran around the upper part of the large drawing room and carved beams like those in the Hall ran across the high ceiling. There were gently worn Turkish rugs on the floor and a crackling fire in the grate. Lady Hilary, the Master’s wife, was supervising two tall young men as they shifted furniture for the new arrivals. Lady Hilary was a tall, slightly awkward woman who Forrester suspected was not quite comfortable in her skin. He liked her, but he was not sure she liked herself.

“I want you to meet Hakon and Oskar,” said Lady Hilary, introducing her two assistants. “The Master specially asked them to join us this evening because they’re from Iceland.”

“And children in Iceland learn the sagas at their mother’s knee,” said the Master genially. “In the absence of Professor Tolkien they will gently correct us if we get our Old Norse pronunciation wrong.”

Hakon and Oskar shook their heads. “No, no, we are engineers,” said Hakon. “It is many years since we read the sagas. But as this is our last night in England, we offer to do our best.” Haraldson said a few words to the boys in Norwegian and they laughed. With Lyall gone, he seemed to have regained his good humour.

“You understand it is because of the ancestors of these young men that the Eddas and the sagas exist,” he said to the rest of the company. “The stories and poems were first created in Norway and other parts of Scandinavia, but they were not written down. When Norwegians went in search of new land—”

“Rather like the settlers in the American west,” said the Master.

“Very much like that,” said Haraldson. “They took the sagas with them to their new home in Iceland. When they became literate, they wrote them down, which is how the sagas survived.”

“In short,” said the Master to the Icelanders, “your ancestors preserved Viking culture when it would otherwise have been lost.” He turned to his wife. “And everything is perfectly arranged, my dear. Thank you.” As the audience settled itself, he addressed the room. “The work we’re going to read tonight, the ‘Völuspá’, is one of the most important poems in the canon. Hakon, Oskar, Professor Haraldson and I will take it in turns to do the reading from the minstrels’ gallery. The acoustics are splendid and when I’ve turned the lights down to help you, imagine you’re listening to genuine Norse bards declaiming from the depths of time.”

Then he ushered the readers through a small door that led to the stairs. Moments later tiny reading lights came on up there and they heard his voice again, speaking from the shadows of the gallery above. As he had promised, the acoustics were perfect, and it sounded to Forrester, as it always did, as if the readers were right beside him.

“In the passage you’re about to hear,” said Winters, “Odin, chief of the gods, bids a certain wise-woman to rise from the grave. She then tells him of the creation of the world, the beginning of years, the origin of the dwarfs. She describes the final destruction of the gods in which fire and flood overwhelm heaven and earth, using a phrase ‘ragna rök’, meaning ‘the fate of the gods’, which has become synonymous with the German word ‘Götterdämmerung’.”

“A subject about which we Germans know all too much,” said Dorfmann wryly. Calthrop frowned, and the reading began.

“I saw there wading through rivers wild,” declaimed Haraldson, sounding like a Viking chief booming down a fjord.

Treacherous men and murderers too,

And workers of ill with the wives of men;

There Nithhogg sucked the blood of the slain,

And the wolf tore men; would you know yet more?

“The phrase ‘Would you know yet more?’ is uttered by the wise-woman,” said the Master. “She is asking Odin if he really wants to hear what is about to befall.”

The giantess old in Ironwood sat,

In the east, and bore the brood of Fenrir;

Among these one in monster’s guise

Was soon to steal the sun from the sky.

There was a rustle of pages as Haraldson handed the book on to the next reader.

There feeds he full on the flesh of the dead,

And the home of the gods he reddens with gore;

Dark grows the sun, and in summer soon

Come mighty storms: would you know yet more?

On a hill there sat, and smote on his harp,

Eggther the joyous, the giants’ warder;

Above him the cock in the bird-wood crowed,

Fair and red did Fjalar stand.

Again the reader changed, but by then the audience was scarcely noticing: through the magic of the incantatory words, combined with the darkness and the firelight, they found themselves transported back to a world where gods roamed the earth and dwarves delved in its depths.

Involuntarily, Forrester’s thoughts went back to what Lyall had said about the Nazi obsession with Norse mythology, and the role the sinister, Nordic-obsessed Thule Society had played in Adolf Hitler’s rise to power. But he knew all this was a perversion of the ancient beliefs: the product of warped minds, with no connection to reality. Except when you listened to a Viking saga being recited in the darkness.

Then to the gods crowed Gollinkambi,

He wakes the heroes in Othin’s hall;

And beneath the earth does another crow,

The rust-red bird at the bars of Hel.

Now Garm howls loud before Gnipahellir,

The fetters will burst, and the wolf run free;

Much do I know, and more can see

Of the fate of the gods, the mighty in fight.

A new reader began: one of the young Icelanders.

Brothers shall fight and fell each other,

And sisters’ sons shall kinship stain;

Hard is it on earth, with mighty whoredom;

Axe-time, sword-time, shields are sundered,

Wind-time, wolf-time, ere the world falls;

Nor ever shall men each other spare.

He paused – and as he paused there was a sharp sound of glass breaking from somewhere outside the Lodge. Lady Hilary looked up, puzzled, then walked over to the window, pulled aside the curtain and peered out. Forrester heard her sharply indrawn breath.

“Michael,” Lady Hilary called up to the gallery. “I’m so sorry to interrupt, but something strange has happened outside. I think you should come and look.” Her voice was oddly flat, as if she couldn’t quite put strong emotions into words. Moments later Forrester and the other guests were all crowded around the window, peering out into the quadrangle. The only light came from the moon, still partially obscured by clouds, but against the whiteness of the snow it was perfectly clear what Lady Hilary was looking at.

Below a broken window on the second floor a body lay spread-eagled in the snow.

3

OPERATION TORCH

They ran out across the untouched whiteness of the quadrangle, the light from the windows of the Lodge behind them – and stopped a few feet from the body of David Lyall, as he lay amidst a halo of broken glass in the otherwise untouched snow, staring sightlessly towards the Lodge.

“My God,” said Peter Dorfmann. “The poor fellow.”

Forrester came forward then, and as he knelt beside the body to check there was no pulse, he saw the puncture wound between the second and third ribs. He looked up at the window from which Lyall had fallen and knew, with a sinking feeling, exactly whose window it was.

“Isn’t that Clark’s set?” asked the Master, his gaze following Forrester’s. No-one replied. “Perhaps I’d better go and see if he’s there.” He began to walk towards the cloisters, then paused and turned to Forrester. “Would you mind calling the police?”

“I don’t think anybody should go up there yet—” said Forrester, but Winters had already disappeared.

“I suppose we’d all better move back,” said Calthrop. “We’re rather messing up the evidence.” It was all too true; half a dozen sets of footprints had trampled the snow into a slushy mass around the body.

“We can’t just leave him there,” said Lady Hilary.

“I’m afraid we have to,” said Forrester. “It’s too late to do anything to help him now.” Suddenly the Master’s wife was sobbing in his arms.

“That poor young man,” she said, again and again. “That poor young man.”

Bitteridge stared at the scene as if it had been designed to give him personal offence. “This is appalling,” he said. “Absolutely appalling.”

The two Icelanders stared, white-faced. Arne Haraldson was frowning, as if trying to solve a particularly difficult crossword puzzle. The remaining guests milled about, wondering what to do next.

The Master’s head appeared through the broken window of Gordon Clark’s room, and Forrester noted blood dripping from his hand where he had cut himself on the glass.

“There’s no sign of Clark,” he called down. “Does anyone know where he might be?”

“He’s probably at home,” said Forrester. “He only uses his set for tutoring.”

“Very well,” said the Master, and disappeared inside again.

“To think it should have happened now,” said Lady Hilary, “when we were all just sitting there, reading. It’s too horrible.” Forrester took her back into the Lodge and handed her over to the wife of a don from Magdalen. Then he went to the Master’s telephone and dialled 999. As he gave the details he felt the nausea return; but this time it was not a response to his own memories, but to the conviction that his friend Gordon Clark had committed an act for which he would eventually be tried, convicted and hanged.

* * *

Forrester heard the clanging bells of the police car from far away, which did not surprise him: he was familiar with the peculiar acoustics of snowy landscapes; there had been times when his life depended on it. The rest of the party, remaining in the Lodge on the Master’s instructions, were sitting around the drawing room in a state of shock; even those with drinks in their hands simply held them, not raising them to their lips. As Forrester watched them he was willing Clark to keep moving, to take a train, get to a Channel port and onto a ferry, to get out of the country as soon as he could.

It was while he was thinking this that he noted Arne Haraldson was no longer present and then, glancing out into the quad, saw him disappearing into a stairway.

Seconds later there was a flash of torchlight in the upper floor.

Almost without thought Forrester slipped out of the drawing room and opened the front door. Bells still clanging, the police car was turning into the driveway, its headlight illuminating the bushes. Forrester melted into the shrubbery even as the car pulled up outside the front door.

As he did so he remembered Lyall taunting Haraldson with his references to Nazis and the occult – and Haraldson’s look of fury in response.

But Haraldson had been in the room with him when Lyall had died: Forrester had been listening to him. It was impossible that he had had anything to do with Lyall’s death.

From the front of the Lodge, Forrester slid into the passageway that separated it from the chapel and found himself in the cloisters below the damaged Lady Tower. He hurried along them until he reached the wooden stairs on which he could still see traces of the snow from Haraldson’s boots.

At the top of the stairs a single forty-watt bulb dangled from the ceiling of the corridor, leaving most of it in shadow. Then his eyes became accustomed to the dark and he could see a pale glow of light emerging from the open door of one of the rooms. Keeping his back against the wall he edged up the stairs and along the landing towards the open door of David Lyall’s rooms.

The light came from under the body lying face down on the floor, feet towards Forrester, dark head pointing towards the window. It came from a torch, trapped under the man’s chest. Below, in the quadrangle, he heard the Master speaking to the police. As Forrester knelt down he saw that his impression the victim’s hair was dark had been wrong: the hair had been darkened by blood, in copious quantities, running from Haraldson’s blond head.

Forrester’s eyes flickered around the room. What had Haraldson been doing here? And who had wanted to stop him? Not Lyall, obviously: Lyall was already dead. The books on the shelves seemed to have been disarranged, and one or two drawers were open. He looked at the shelves: English classics, some Russian novelists; nothing unexpected.

He stood back for a moment, contemplating the room as a whole, glanced at the ceiling; the plaster seemed to be intact. He knelt down again beside the Norwegian and as he examined the floorboards, felt a pair of massive hands clasp themselves around his throat.

“Du jævla drittsekk!” said Haraldson – and began to throttle him. For a moment Forrester was too startled by the realisation that Haraldson wasn’t dead to do anything to defend himself, and when he grasped the man’s wrists and began to tear them away from him he found it was impossible: the Norwegian had the strength of a berserker.

“It’s me, Forrester,” he croaked, but the other man’s eyes were wild and Forrester was certain his words had had no effect.