Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Paris 1890. SHERLOCK HOLMES is summoned across the English Channel to the famous Opera House. Once there, he is challenged to discover the true motivations and secrets of the notorious phantom, who rules its depths with passion and defiance.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 463

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

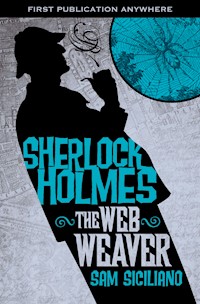

AVAILABLE NOW FROM TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES SERIES:

THE ECTOPLASMIC MAN

Daniel Stashower

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

Manley Wade Wellman & Wade Wellman

THE SCROLL OF THE DEAD

David Stuart Davies

THE STALWART COMPANIONS

H. Paul Jeffers

THE VEILED DETECTIVE

David Stuart Davies

THE MAN FROM HELL

Barrie Roberts

SÉANCE FOR A VAMPIRE

Fred Saberhagen

THE SEVENTH BULLET

Daniel D. Victor

THE WHITECHAPEL HORRORS

Edward B. Hanna

DR JEKYLL AND MR HOLMES

Loren D. Estleman

THE GIANT RAT OF SUMATRA

Richard L. Boyer

COMING SOON FROM TITAN BOOKS

THE PEERLESS PEER

Philip José Farmer

THE STAR OF INDIA

Carole Buggé

THE ANGEL OF THE OPERA

SAM SICILIANO

TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES:

THE ANGEL OF THE OPERA

ISBN: 9780857685391

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

First edition: March 2011

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 1994, 2011 Sam Siciliano

Visit our website:

www.titanbooks.com

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address. To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive Titan offers online, please register as a member by clicking the ‘sign up’ button on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed in the USA.

To my mother, for introducing me to Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan of the Apes, and the Land of Oz. She tolerated my youthful vampire novel, but this is the book she would have been proud of.

Contents

Dear Reader

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Afterword

Dear Reader,

The following manuscript was written in the summer of 1891, shortly after the events recounted herein. My purpose at the time was to reveal the real Sherlock Holmes as corrective to the ridiculous fictional creation of John Watson. Holmes was my truest friend and my cousin, his mother, Violet Sherrinford, being my mother’s sister. However, when in 1892 I showed Sherlock this account of our adventures in Paris, he asked me, quite sternly, not to publish it. Watson’s writings he thought bad enough; far worse to have his true character revealed, his soul bared to the masses! He was also concerned about the privacy of others.

With regret I yielded to his wishes, and over the years, as yet another of Watson’s foolish stories appeared, I gritted my teeth and tried to master patience. Now that Sherlock, God rest his soul, and John Watson are both dead, I can finally publish what was truly Holmes’s strangest case. The devil’s foot business cannot possibly compare with this.

Sherlock Holmes was a much more interesting, a much deeper, man than Watson rendered him. Watson had little imagination and was extremely conventional in the stuffiest British sense. His accounts transfer that same conventionality to my cousin, including the typical British imperialistic sentiments of the day. Nothing could be more false! Sherlock was also extremely cynical about contemporary religiosity. When Watson has him declaiming that the beauty of a rose reflects the Creator or lecturing a maimed woman against suicide, he was creating pure fiction. Sherlock was an agnostic, and he despised smugness and cant.

Watson could be quite obtuse about Holmes. For instance, he took my cousin’s disdain for the fair sex at face value, never wondering if perhaps “the lady doth protest too much.”

Watson was accurate in his physical description of Holmes, but Sydney Paget’s drawings were highly idealized. My cousin was not so handsome, nor did he resemble the actor Basil Rathbone! His hawkish nose threw his face off balance; his hair began to recede in his late thirties; his lips were thin; and he had a weak chin. All in all, he had a certain grotesque quality, his skeletal frame, his blazing eyes, pale complexion, and large nose all contributing to the impression. My frankness here may seem unkind, but his heart and his mind were what made Sherlock Holmes great.

He could be a difficult man to live with. As even Watson notes, he alternated between periods of frantic activity and black depression. During the latter, thoughts of death, evil, and his own failings tormented him, but to his dying day, he was not one to confide in others. Watson and he were temperamentally poles apart, and their relationship was nowhere near so rosy as in the stories. In fact, a major row separated them for several years. Watson was so angry that he promptly invented Moriarty and killed off my cousin (much to Sherlock’s relief) at Reichenbach Falls. The events I recount took place shortly after that falling out.

It is probably rather obvious by now that Watson and I never much cared for one another. I cannot forgive him for parading so distorted, so petty a rendering of my cousin before the public for all those years. Since I, too, was trained in medicine, I can state that his failings as a physician were even greater than those as a writer. I encountered several examples of his incompetence firsthand!

But I must be charitable to the dead. Even after all these years, Watson still warms my old blood! This book is about Sherlock Holmes, not John Watson, and I hope the reader will not be displeased to discover Holmes, “warts and all.” Despite his faults, he was a great and generous man, the finest I have ever known. My wife and I named a son after him, and we who loved him still miss him deeply.

I have made few alterations in the manuscript, leaving my youthful enthusiasm intact. Those were gentler, more innocent times, when mankind could still look to the future with wonder and hope instead of despair. Often have I wished that I could leave this dark, wretched twentieth century and return to the 1890s to again walk the streets of Paris with Sherlock Holmes.

Doctor Henry Vernier

London, July 1939

Prologue

Sherlock Holmes stared at the goddess of death, the incarnation of evil, while I, being of a less melancholic nature, mused upon the young woman playing the piano.

Wales in January–the large hall of the ancient castle cold and empty, a major blizzard raging outside. Susan Lowell’s music, more than the coal glowing in the fireplace, lightened the darkness and warmed us. Her powers as a musician were extraordinary, but I lack my cousin’s technical understanding of music and his perfect pitch. Harmonic theory, sonata allegro form, and fugues are mysteries to me. I enjoy serious music, but it takes a clumsy player indeed to deviate so much from the rhythm or pitch that my ear (clumsier still) can detect the variance. The woman’s physiognomy and her beauty were what drew my attention.

Her face displayed both her Indian and her Anglo-Saxon heritage. She had the large, almond-shaped eyes, the long, straight nose and narrow face, the combination of delicacy and dignity, so often found in the women of India. Sadly, the trachoma which had left her nearly blind had thickened and disfigured her eyelids and cast a film over her stunning black eyes. The effects of the disease were only too familiar; I had seen them everywhere in the Orient. Her hair was not pure black, but had a brownish cast inherited from her father, and her skin, too, was paler than that of a pure-blooded Indian. Her dress, however, had nothing of the exotic: her hair was bound up in conventional British or French fashion, and she wore a dark skirt and a white shirtwaist made of silk. Her long brown fingers stretched with ease to strike Chopin’s chords.

I could not help but reflect upon the two absurd blows fate had struck her. Still in her early thirties, Susan Lowell was beautiful, sensitive, intelligent, and wealthy; but no family of even modest pretense would allow their son to marry a half-caste. Some simpering blonde with the intelligence of a spaniel, gladly–but never one such as she! Nature had also treated her unkindly, afflicting her at an early age with a disease virtually nonexistent in the temperate climate of England. Had her father returned sooner to his native land, she would still possess her sight.

Although she was slender and of moderate stature, there was nothing meek or mild in the thunderous conclusion to Chopin’s piece. She let the final chords fade slowly until silence had once again claimed the massive chamber. At last she sighed, and the flush on her cheeks also faded.

Sherlock turned from the statue. “Bravo.” He clapped his hands. “Really most excellent, Miss Lowell. I have not heard Chopin played better.”

“I am no music critic,” I said, “but it was beautiful.”

She smiled, turning her head toward me, but her eyes stared vacantly into space. “Thank you, gentlemen. It is vain, I know, but I enjoy having an audience. However, it is very late, and I am weary.”

I stood. “It was boorish of us to let you continue for so long, but your playing was utterly captivating.”

She smiled again. “You are very gracious, Doctor Vernier. Catherine.” Her maid took her arm, but she needed little guidance in so familiar a room. “Until tomorrow, and I hope, Mr. Holmes, that you will again join me on the violin.”

“You have my promise, Miss Lowell. You know the Kreutzer?”

“Indeed, yes.”

“I shall look forward to it.”

Sherlock stood rather stiffly. I reached out and gave her arm a squeeze. It felt soft under the smooth silk. “Thank you again, Miss Lowell.”

The smile she gave me made me wish briefly that my affections had not been pledged elsewhere. How I missed Michelle! Sherlock waited until she had left, then withdrew his pipe, lit it, and soon exhaled a cloud of smoke.

I coughed once, and he gave me a twisted, sardonic smile that seemed completely unrelated to Miss Lowell’s radiant expression. He wore his customary black frock coat and gray striped trousers; his face was pale and tired. “A foul habit, Doctor, but one of a very fixed and determined nature. You seem rather taken with the young lady.”

“She is not only beautiful, but has a quick mind and a generous nature.”

“I see you have noticed her interior qualities as well.”

I smiled. “It required no great powers of deduction.”

“Indeed? Then it is surprising there is not a crowd of fine young fellows courting the lady.”

“That is because the world is filled with fools.”

“The same thought had occurred to me.”

“I noticed you seemed more occupied with another lady, one of a more bloodthirsty disposition.”

Holmes nodded. “She is indeed a woman of a different stripe.” Slowly he approached the statue, then stood with folded arms, his pipe in one hand. “She is ghastly, is she not? Kali Ma, the Black Mother, the goddess of murderers and assassins, the goddess of blood and death.”

“It is strangely beautiful.”

“Do you think so?”

“Yes,” I said, “in a perverse sort of way. Certainly Major Lowell must think so to have kept it all these years.”

Sherlock gave me another brief, crooked smile, but his gray eyes had an odd glint. “I think she is the most truly ugly thing I have ever seen or am likely to see.” He put the stem of his pipe between his lips.

The statue had been carved from black marble, and the smooth polish of the stone clashed with the roughness of execution and the hideousness of the subject. Kali, the Black Mother, stood nearly three feet tall. A corpse carved with exquisite detail hung from each earlobe. An equally elaborate necklace of skulls hung about her neck, falling below the pointed breasts, and at her waist was a girdle made up of a double row of severed hands. One of her four arms held the head of a giant, another a sword with a curved blade, another a terrified man. Her free hand was raised in an upright gesture. She stood upon the crouching form of another god, one leg raised and bent. Her tongue thrust grotesquely from her mouth, and her eyes were two blood-colored rubies. Unlike the dusky marble, the gems had the trick of catching any stray light so that they had a faint, disconcertingly life-like glow.

“The jewels are beautiful,” I said. “They must be worth a fortune.”

“In themselves they might be beautiful, if you could remove them from so polluted a context. However, I think they will always remain the eyes of the goddess of death.”

“You are keeping something from me. In your best consulting detective manner.”

“Nothing which should not be rather obvious. By the way, I received this note today forwarded from London. Read it.”

My eyes widened. Written in French, it was a solicitation from L’Opéra de Paris, signed by Messieurs Richard and Moncharmin, asking for his aid in clearing up the matter of an “opera ghost” who had been disrupting things. “This sounds like the very case for you. It appears to have everything.”

“Would you care to accompany me, Henry? I shall want to be there in a fortnight. I could use your services.”

“You’re joking. You know I have absolutely no skill at detection.”

“True, but your command of the language would be helpful.”

“Sherlock, you speak excellent French.”

“But I have had no practice for some time, and I do have an accent.”

“A very slight one.”

“Perhaps, but enough to give me away. That accent will limit where I can go and what I can discover. You would have no such limitations. Besides, we shall stay in an excellent hotel, dine like royalty, and no doubt attend several performances gratis. Only the French can do Faust justice, and there are rumors of some new sensation doing Marguerite.”

I laughed. “You know I am no great opera enthusiast, but the hotel and the cuisine are very appealing. I would be glad to come. I have not been to Paris for two years now, and any excuse would suffice–not that I do not enjoy sharing your adventures. Michelle will cover our practice for me. Oh, she will not want me to rush away again so soon, but I shall persuade her. I shall have a week to shower her with my attentions.”

Holmes nodded. “Good. It’s settled then.” He drew in deeply on his pipe, his eyes drawn again to the statue. “We are almost finished here.”

“Almost? Have you not captured the last of the thugs? The threat to Major Lowell and his daughter is gone.”

A cloud of white smoke drifted from his lips, but his eyes remained fixed. “Perhaps. There remain a few... details.”

“That statue certainly fascinates you.”

“Evil has always fascinated me, Henry, and I doubt I have ever seen a case of purer, more unrefined evil than this.”

“But the thugs, in the end, did not amount to much. Life is very simple for them. Their mission is to strangle as many of their fellow creatures as possible for their goddess there. They were out of their sunny Indian element here in the cold wastes of Wales. I almost felt sorry for them, having to deal with the English winter and the net Sherlock Holmes had laid for them. Major Lowell should not have shot them, you know. Murderers many times over they may be, but they deserved their chance before a court of law and an English jury.”

“Major Lowell had an excellent reason for shooting them.”

“Indeed?” I said.

He took his pipe from between his lips, but said nothing.

“Sherlock, will you stop staring at that cursed statue and explain yourself.”

Another cloud of smoke came from between his lips, then he turned to look at me. “You will understand soon enough.”

“Ah, my friends, still admiring my statue, yes?”

Major Lowell was in excellent humor. He wore a crimson velvet dressing gown and held a large cigar, which my physician’s instincts made me wish to pluck from his lips. From his accounts of his involvement in India during the thirties, I knew he must be well into his seventies. His color was never good, and I could tell from being around him for the past few days that he suffered from shortness of breath and angina. His hair was quite white, the bushy sideburns connected to a large white mustache, but his chin and jaw were smooth shaven. The style had been the rage decades ago. His face was flushed, probably from drink, but the skin about his eyes had a sickly grayish cast.

Holmes nodded. “In many ways I consider her the key to the entire case.”

The hint of a frown clouded Lowell’s brow. “You do?”

Sherlock stared at the statue. “You contacted me shortly after Colonels Davidson and Broderick were found dead. You recounted your shared experiences in India more than fifty years past when you were part of British efforts to suppress the ‘thugs,’ ritual murderers and assassins who killed thousands in the name of their goddess Kali. Both Davidson and Broderick appeared to have been strangled by thugs, intruders from the past seeking vengeance. You feared you were next.”

Lowell’s smile had returned. “Quite so, Mr. Holmes, and a good end we have seen to this troublesome business.” Sherlock stared at him so long before replying that the old man began to fidget nervously with his cigar.

“A very convenient end, two of the men dead, including the priest who led them, and the other two in police custody. How fortunate, also, that those two speak not a word of English. It would be interesting to discuss their fierce goddess with them. Alas, I have studied most European languages, but not Hindustani.”

The Major shook his head. “A barbaric and ugly tongue, Mr. Holmes, hardly worth your trouble.”

“Ah, but as a near relative of Sanskrit, the mother tongue of all our Western languages, it would be fascinating. Anyway, Major, all your enemies are conveniently eliminated, and now you may dwell in peace during the remainder of your days.”

“All thanks to you, Mr. Holmes.”

Sherlock set down his pipe on the table next to the statue. “I fear that there is still one complication.”

“Complication?” Lowell echoed.

“Yes, Major Lowell. The complication is that you yourself are a thug.”

I have never seen a man so transformed as Lowell was at that moment. The cigar fell from his lips, and all the color went out of his face, his lips turning bluish. I would have been more concerned for his health had I not been so totally surprised myself. “Sherlock, what are you saying?”

“I am saying that Major Lowell is and has been a thug, and not in the quaint, colloquial usage of the word, but in its darker, original meaning. Instead of acting with Broderick and Davidson to suppress the thugs, he was secretly a devotee of the black goddess. As such he has betrayed everything: his compatriots and his commission as a British officer, his country and queen, even the Christian God.”

Lowell put one hand on his chest, then turned and sank back into a massive oaken chair. The thick sturdy oak contrasted with his own frail and aged frame. “This is... a monstrous lie, some terrible joke.”

Holmes shook his head grimly. “Not at all. Your devotion to your hideous goddess has blinded you, made you careless and stupid. Why would a man who had spent many years trying to stamp out murderous fanatics keep an image of their deity prominently displayed in his home?”

“A memento only,” Lowell mumbled. Unconsciously he had begun to wring his hands.

“Surely it has some appeal as a work of art,” I said. “This cannot be true.”

“Yes, yes.” Lowell nodded eagerly.

Holmes again shook his head. “Are you blind, Henry? Look at that thing, study her closely. She reeks of blood and death. You carry aesthetic detachment too far. Besides, I have further proof, even though it was the statue that first convinced me that Major Lowell was not the man he pretended to be.”

“Proof?” Lowell whispered.

“Yes, proof. There were many small details which did not fit, and of course there was your obvious zeal to shoot the two men, one as elderly and infirm as yourself.”

“He was dangerous! I knew his powers! I have seen his tongue mesmerize the masses, their black eyes fill with the love of blood and slaughter! No one would have been safe while he lived.”

“Least of all you, Major Lowell.”

“This is... preposterous, an outrageous insult!” Somehow the old man managed to stand up, but he clung desperately to the chair with both hands. “You have no proof–this is all supposition! Get out of my house–go, at once!”

Briefly I thought I saw pity in Sherlock’s face, but it was gone almost at once. “I have all the proof I need, Major Lowell.” He withdrew a folded paper from his coat pocket and opened it. A large reddish-brown splotch, clearly dried blood, marred one corner. “This is the letter you wrote the priest to entrap him and his friends. This explains their walking right into our hands. I found this on the dead man, despite your efforts to get rid of the body as quickly as possible. You were not so stupid as to sign this, and you made some attempt to disguise your writing. Not enough, however, to fool me or any other handwriting expert. You address the priest as an old friend and fellow believer, Major. I suspect, although I do not yet have proof, that you were an accomplice in the killings of Broderick and Davidson. One did die, after all, under your roof.”

I felt a sickening dismay and could not bear looking at the frightened old man. “Can he be such a black traitor, such a... monster?”

Sherlock gave a curt nod. “Yes.”

Lowell’s hands tightened on the chair back, his knuckles white. He opened his mouth, a grimace baring his brown, worn teeth. “You are so smug, so condescending–the great Sherlock Holmes! What do you know of evil, real evil! Have you ever cut open a man, torn his heart from his chest and bathed your arms in blood? I have killed more men than you will ever save.” He stared at the statue, a shuddering sigh slipping from between his bluish lips, then a dreadful energy animated him, filling his eyes with power.

“You yourself cannot be such a fool as to believe in the Christian God, that comical hodgepodge of banal goodness and petulant destructiveness–I am certain of it! But you are too weak to turn to the dark one, the Black Mother. Evil rules the world, Mr. Holmes, touching all things with her black fingers–even you and that youthful fool with you. Can you blame me for choosing the winning side? The goddess of death and destruction will reign long after this ridiculous empire of ours has fallen and only our absurd monuments remain. Can you blame me for choosing Kali? You understand–I know you do! You feel her power! You know she is no mere statue, but the true goddess who must be obeyed and worshiped! Look into her red eyes, into those bloody orbs, and then tell me I am wrong!”

Tears ran from his eyes, but he began to laugh. He was so old and sick that the sound was feeble, yet I heard such madness, such hatred and pain, that I wanted to clap my hands to my ears.

Sherlock wrenched the chair away from Lowell, then used both hands to raise and swing it. The blow sent the statue crashing to the floor. The oriental carpet did not go all the way to the wall, and the marble struck the stone of the castle floor and shattered. The impact broke off two of the black marble arms and the fearful head itself.

Lowell had slumped against the wall, but he screamed, “No!” Where he got the strength for such a cry I do not know. He staggered forward, but I seized his arm.

“It is finished–you will make yourself ill.”

“My statue! My statue!” He began to weep, and if I had not held him up he would have collapsed. “You have killed her, you have killed her. She was so beautiful.”

“Good Lord, Major–sit down. You are not well.” I helped him to another chair, the mate of the one lying on the floor. I turned to Sherlock. “Are you all right?”

He was fearfully pale, and I could see his large white hands quivering at his sides. The fury still showed in his eyes. He nodded. “Yes. I’m fine.” He bent over to retrieve his pipe, then raised the chair. He was of such a tall and slight build that these occasional feats of strength always amazed me. I have seen him so weary from lack of proper sleep and diet that he could hardly stand up, and yet he could hurl an oak chair of a good five stone as easily as if it were a pillow.

“For God’s sake, Mr. Holmes, spare me–spare me!”

“A moment ago you mocked the Deity, Major Lowell.”

“Please, Mr. Holmes, if not for my sake, for my daughter’s. It would destroy her to know. She has no inkling. She and her mother were the only good things that ever happened in my wretched life. Her mother was gentle–while she lived I turned from the black goddess. My fellow officers mocked me, and there was no longer a place for me in the regiment. What did I care? But when she died, when she left me, I grew weak again, and your wretched God–he blinded my little one when she was hardly more than a babe! Can you blame me for choosing Kali? Don’t tell her, Mr. Holmes, I beg of you!”

Holmes and I stared at one another. “You need some brandy, Major,” I said. “Calm yourself, please–as you say–for your daughter’s sake.” I walked to a nearby table and poured brandy from a heavy crystal decanter.

“Please, Mr. Holmes. What would be the harm? You are a gentleman, I know, and a reasonable man. Let us forget this disturbing business. They were only dirty Indians. We are white men, are we not? As a white man and an Englishman, I implore you...”

Sherlock’s pipe toppled from his hands, and he stepped forward. I dropped the glass, spilling its contents onto the carpet, then lunged forward and grabbed his arm. “Sherlock, he is old and sick–you cannot strike him!” He turned, and for a moment I thought he would hit me instead.

“Tell him... to keep silent.”

The old man was still weeping and blubbering about his daughter. “Major, please,” I murmured. “I think we could all use some brandy. I know I could.” I let go of Sherlock.

“I’m sorry, Henry,” he whispered. “Yes, get me some brandy.”

Soon we were all sipping silently at the Major’s excellent Cognac and not tasting it. Outside we heard the icy, lonely howling of the wind. At night there is no more melancholy a sound. I remember as a boy cowering in my bed in the cold and dark of a winter night, listening to that unceasing moan. None of us said anything for a long while.

Finally the Major spoke, but the furor which had possessed him was gone. He sounded old, sick, and weary. “You are right, Mr. Holmes. I have betrayed every trust given me, save one. My daughter will tell you that I have been a loving father. I have cared for her. That is why... If only myself were involved, I could bear the disgrace, but she has done nothing–nothing at all. Some merciless god has already punished her enough. Why should...?” The old man’s voice faded, and he began to weep in earnest.

Holmes and I stared at each other. He was tired and discouraged, his own energy spent. I stood and helped the old man up. “Go to bed, Major. You are weary. We shall continue this discussion in the morning when we have all rested.”

The old man tottered in my grasp. He felt unbelievably light, the flesh and muscle wispy nothingness over the hard bone.

He took a few steps with my aid, then turned again to Sherlock. “Mr. Holmes, I have but one final thing to ask of you.” Holmes raised his head, but his eyes were evasive. “Promise me, promise that you will look after my daughter.”

“What?”

“Promise me you will look after her. I have no other living relations. She has little experience with men save her father. When the two of you played that German music yesterday, I could see that you understood her. She respects you. Her musical powers are a mystery to me, the more so because of her blindness. Whatever happens to me, howsoever I am punished for my sins, I beg of you to look after her. Will you promise me that? I beg of you, sir. Please.”

The blood suffused Sherlock’s face in a slow flush, and he looked away.

“Good God, Mr. Holmes–you have destroyed me! It is only fair. Promise me you will watch over her for me.”

“Major Lowell, it is late, and...” I began.

Sherlock did not look up, but he spoke softly. “Very well. You have my promise.”

The old man sagged in my arms, and again I thought he would collapse. “Thank you.”

He let me lead him down the long corridor to his bedroom. The butler and I exchanged knowing looks. The Major shuffled along, taking very small steps and not saying a word. The cry of the wind was fainter here. We stopped before the doorway.

“I will look in upon you shortly, Major. I can give you something that will calm your nerves and help you sleep.”

“You are very kind, Doctor Vernier.” His eyes were red from weeping, but the bluish tinge had left his lips. I doubted he could live more than another six months.

He closed the door, and I started back down the hallway, a prey to the clash of conflicting emotions. The man was guilty of terrible bloody crimes, but I questioned his sanity. Moreover, he was old and sick, only a step away from the grave. What would be the benefit to anyone should he go to the gallows now? It would bring back none of his victims, and there was his daughter. She was as innocent as he was corrupt.

Sherlock had crossed his legs, the upper foot bobbing rhythmically. His pipe was relit, and the empty brandy glass sat on the table beside him. I shared his melancholy sentiments.

“What is to be done?” I asked.

He shrugged and shook his head.

“It was kind of you to promise to look after his daughter.”

His sardonic smile returned briefly, even more harsh and humorless than usual. “He had cornered me. He left me no choice.” He inhaled deeply from the pipe.

I poured myself more brandy, shivered, then took a deep swallow. “Lord, it’s cold in here. This business has shaken me, I can tell you that. You may be used to it, but I... What’s wrong, Sherlock?”

He shrugged. “What’s right, Henry? Nothing. Nothing at all. The great Sherlock Holmes reduced to striking a sick old man in a rage. If you had not restrained me...”

“You were provoked.”

He gazed at the statue on the floor. “At least that thing is destroyed. There was, Henry, a certain perspicuity in his ravings.”

“No.”

“Yes. Do you think one can stare into the face of evil as I have, the face of the Black Mother, follow her every manifestation, and still remain untouched? I struggle with my opponents at the edge of an abyss, and even if I win, they may pull me over. Hamlet has a line, which escapes me, about a virtuous man being caught up in the general censure. It is the greatest danger I face. I have seen too much that is sordid and wicked; it is hard not to despise the human race–including myself. Evil and hatred are powerful forces. Who indeed can face them without being corrupted? I was ready to kill that pathetic old man.”

“You might have struck him, but you would never have killed him.”

“No?”

“Of course not.”

Holmes sighed. “This is one of the blackest cases I have ever seen; yet if I turn the Major over to the police, am I not killing him in a slower, more ruthless and brutal manner? Would it not be better if I struck him dead or put a bullet through his heart?”

I opened my mouth, then closed it.

We both remained silent, then he smiled. “Watson would no doubt have had a ready answer for me.” I glared at him, which made him laugh. “Who am I punishing if I expose him? He cannot live much longer.”

“Six months, at most.”

“Exactly. One way or another, he is dead in a year’s time, but his daughter will not be. She will have to live the rest of her life knowing her father, her only relation, was a great villain. Where is the justice in that, Henry?”

“There is none.”

“Then you think I should remain silent?”

I hesitated, then finally said, “Yes.”

He ran his hand back through the dark, oily hair over his broad forehead. He did not look particularly well himself. “I am glad to hear you say so.”

We were both relieved. “Perhaps I will go tell him, Sherlock. He will sleep better, I am sure, if one can sleep with such crimes blackening one’s soul. He seemed so distraught I...”

The same thought struck us both. I set down my glass, and Sherlock stood abruptly. “How could we–how could I-be so blasted stupid?” He turned and strode toward the hallway.

I followed. “Perhaps...” But I was too sick at heart to speak.

The wind was louder now, even in the corridor. The door was not locked, and when Sherlock opened it, the chill of the stormy night and a few snowflakes swirled about us. For some reason, Major Lowell had opened the shutters to his window. He hung in the center of the room, snowflakes shimmering about him in the gray-white light. His face and his bare, bony feet were bluish white, and he turned slightly with the wind. A piece of silk had been tied to a hook in the ceiling, the noose placed about his thin throat; now his weight stretched it tight; and in the dim light, I could barely make out that the silk was red, the color of blood.

I had seen many dead and dying men, but this was all too much for me. My own hands felt icy. I turned away and stepped back into the hallway.

Holmes’s voice was steady and distant. “His goddess has claimed her final victim.”

Holmes and Susan Lowell played well together; even I could hear that. With Watson’s emphasis on the cerebral–the rational side of Sherlock’s nature–the violin seemed another oddity, an eccentricity like revolver practice in the parlor of his rooms. However, anyone who ever heard him play, who heard him actually spinning out the long quivering lines of Beethoven’s melodies, bringing the mere notes alive, filling the room with their power and sensual warmth, knew better than to consider him some mere brain, some unfeeling lump of intellect. Beneath all that ice was fire. Mastering any instrument requires intelligence, yes, but that which separates the mediocre from the inspired is a matter more of instinct and feelings.

Miss Lowell was equally inspired. They had been very good before, but today they outdid themselves. As she played, her unseeing eyes remained locked straight ahead, but she managed unerringly to make the leaps in the bass to the left of the keyboard. Although she had no real sight, seeing only shapeless gray light, she had total command of the instrument. She had related how, as a child, she had picked out melodies by feel alone and how she had begged her father for lessons. Finally he had relented. Within a few years, she could hear her teacher play a piece once or she could attend a concert, then play back the music without missing a note. Sherlock had remarked on both her perfect pitch and her incredible memory. He had never met her equal. All in all, seeing her play was like watching a miracle, some great mystery, manifest itself.

The last movement, the presto, went very quickly. The end was sudden: her hands struck the final chords even as Holmes’s bow glided across the strings for the last time.

“Bravo,” I cried, rising to my feet and applauding. “Bravo!”

Holmes lowered his violin, set down the bow, then took the white handkerchief off his shoulder and wiped his face. “Bravo, indeed, Miss Lowell. You are among the foremost musicians I have ever been honored to hear, let alone accompany.”

“You are too generous, Mr. Holmes.”

“Not in the least.”

“Besides, I was the accompanist, not you. Your violin was the hero of the piece. I had no idea.... Your reputation as a detective preceded you, but I had never imagined you could be a musical genius as well.”

Perhaps because she could not see him, Sherlock let his face briefly reveal his satisfaction. “Now it is you who are too generous.”

She smiled so warmly, her face so radiant, that I wanted to whisper to him to squeeze her hand or at least touch her shoulder, but he stood rather stiffly and again wiped his brow with the handkerchief.

“I feel so happy, and yet...” The tears slipped down the dark skin of her cheeks. “It is wrong with father... But I know he would want me to–and after all, you are leaving tomorrow. Oh, blast it all.” Abruptly she sat down on the piano bench and began to weep in earnest.

Since I had been expecting some such outburst of grief, I was not surprised. The night before last, after Holmes and I had cut down her father, we agreed, with the concurrence of the butler Russell, that the Major’s bad heart was to be the cause of his death. My being a physician made the matter quite simple. We had broken the news to her yesterday morning, and she had born it courageously, shedding until now only a few tears.

Sherlock and I stared at each other, then I lay my hand gently on her shoulder. “We are very sorry, Miss Lowell.”

“You have both been very kind to me.” She dabbed at her eyes with a handkerchief. “I... I am being very selfish.”

My brow wrinkled. “How so?”

“I loved father, and I shall miss him, but... I fear... I worry more for myself. The days–the years–seem so long at times, so very long. Sometimes I... I fear for my sanity, and I pray for death.” Her voice was almost a whisper.

“You cannot mean that, Miss Lowell.”

“Can I not? What have I to live for?”

I opened my mouth, then hesitated. I loathed physicians who mouthed Polonian platitudes and gave false reassurances, but nothing else came to mind. “You... you...”

“Tell me truly, Doctor Vernier, and you, Mr. Holmes, are we of Indian descent... repugnant? Let me know the truth, as you are my friends. Do you find me so very ugly?”

A pained laugh slipped from my lips. “Miss Lowell, you are far from ugly. Who has told you such lies?”

“Why, then, do so many shun my company? We have had few visitors and little mingling with our neighbors, but I could hear the coldness in their voices. My father claimed I was beautiful, but I knew he would do anything to shelter my feelings. I feared... I must be ugly compared to others, either my race or my features making me despicable. As you are my friends, I beg of you not to spare my feelings–I must know the truth.”

I squeezed her shoulder gently. “In God’s name, Miss Lowell, you are one of the most beautiful women I have ever known.”

Her blind eyes stared into the shadowy part of the room, and you could see confusion writ upon her lovely face. She was silent, then said, “Mr. Holmes?”

Sherlock’s fists were clenched, and his own eyes were filled with a strange passion. “Henry–Doctor Vernier–has spoken the truth. You are... beautiful.”

Her astonishment seemed genuine. Over the years she must have pondered the matter deeply, seeking to comprehend her isolation. Since she could see neither herself nor others, she could not judge for herself. Little wonder she had come to consider herself ugly.

“Can this be true...?” she whispered.

“Yes, Miss Lowell.”

She began to cry again. “I don’t understand. I don’t understand.”

I hesitated, then asked, “What is it?” Sherlock’s eyes blazed at me, and I could tell he wanted us to leave the room.

“Why am I so alone? If I am no freak, why must I be so alone? Why are the consolations, the affections, granted to other women, denied to me?”

“Prejudice and stupidity, Miss Lowell–they blind others to your attractions. Believe me, if...”

“I thought also that it might be my wickedness.”

“Wickedness?”

“Yes. I... I have strange, morbid thoughts and... wicked longings. Oh, why must life be so wretched–why?”

Again I could not bring myself to utter some hearty banality. I glanced at Holmes. His face was pale and pained. He motioned toward the door, but I could not leave her so desolate.

“Please, Miss Lowell. Don’t... We have not known you for long, but we do consider ourselves your friends.”

She drew in her breath, straightening her spine, then let out a final shaky sob. “Thank you, I am being very selfish, I know, but...”

“No.” Sherlock’s voice was very loud, and she turned her head in his direction.

“I shall be... fine,” she said. “I have–there is my music, after all. When I play as we did, Mr. Holmes, I forget everything else. There is no suffering, no blindness, no time, only the music everywhere, washing over everything, even my troubled spirit. How foolish I must sound to you both. I am sorry if... Please leave me alone for a while. I feel such a fool, but the time which lies before me–the hours, days and years which stretch into the darkness of the future–it seems so vast and empty, such an abyss.”

“Miss Lowell...”

“Please leave me, Doctor Vernier.”

She regained her composure, and I felt I must honor her request. Sherlock’s mouth twitched. He had grown more and more agitated as he had listened to her.

“Very well,” I said. Sherlock and I started for the door.

Suddenly he stopped and turned. “Miss Lowell.” His voice was so loud the words had a faint echo in the vast stone chamber.

She raised her head, held her handkerchief loosely in her right hand.

“Yes?”

“We are indeed your friends. I–I am your friend. You can count on periodic visits, and if you ever require anything, you need only ask for it. My cases require much of my time, and often the fate of men or nations hang in the balance. All the same, if you summon me, I shall come as quickly as I possibly can. I hope you understand.”

“Oh, Mr. Holmes–you offer me more than I have any right to expect.”

“Also, once your period of mourning is at an end, you might consider moving to London. A musician such as yourself is wasted here. I know many in the London musical circles and could introduce you to those who could not fail to recognize your talent.”

She began to cry again, but now her face was joyful. “I do not deserve such kindness. Oh thank you, thank you both.”

Holmes clenched both hands into fists, took one step forward toward her, then stopped. “We will speak of this later... when your sorrow has abated.” He whirled about, then strode toward the door without looking at me. I followed him. In the hallway he took out a cigarette and lit it, his hands trembling slightly.

“You seem greatly moved.” My voice had a faint tinge of irony.

“Not really. I... human suffering always discomforts me, especially unnecessary suffering.”

“To think that all these years she has considered herself some homely freak. Strange, is it not, when she is so beautiful?”

He exhaled a cloud of smoke. “Very.”

“You seemed quite interested in Miss Lowell, and she in turn seemed particularly interested in what you had to say. You do not believe in ‘tainted blood,’ do you? The sins of the fathers being passed on to the children, and so on.”

“Utter rubbish.”

“Then you might be of more direct assistance to the lady.”

“You know my views on the fair sex.”

“Come now, I am not Watson. Do you think I, too, am blind? It did not require your fabulous powers of deduction to see something of your feelings just now.”

“Don’t be ridiculous, Henry. I have no need of an alienist to sort out my mental states. Kindly keep such counsels to yourself. Tomorrow we return to London, where I have some other business to finish. Can you be ready to leave for Paris in ten days time?”

“Yes.”

“Good. The situation at the Opera sounds most interesting, and Paris will be a welcome change after this Welsh desolation.” He dropped his cigarette, then with the toe of his boot crushed out the butt on the gray stone.

One

Holmes and I paused before the portal to Le Palais Garnier, the Paris Opera House. The February sun illuminated the columns, arches, busts, friezes and reliefs, shone on marble, bronze, stone, and wood. Along the very top of the building was a row of masks, their grotesque faces with black O’s for mouths and eyes gazing down upon the Place de l’Opéra. Their oddly abstract faces did not match the style of the conventional representations covering the facade. Just below the words ACADEMIE NATIONALE DE MUSIQUE was a row of busts, Mozart above our doorway, Beethoven to his left, Spontini to his right.

“Who was Spontini?” I muttered.

“A minor opera composer who was briefly court musician to Louis XVIII, two of his better known works being La Vestale and Fernand Cortez.”

I wondered briefly at Holmes’s capacity for remembering trivia. The Opera was clearly a secular temple, another of the monuments Napoleon the Third wished to erect to himself and Paris. Determined that his capital should have the largest, most splendid theater in the world, he had chosen Jean-Louis Charles Garnier as architect and builder, then lavished huge sums on its construction. Ironically, although begun in 1861, it was not completed until 1875, some five years after the collapse of the Second Empire. All the same, it remained a monument to that period between 1850 and 1870 when Louis Napoleon had transformed Paris into the modern city of today. Even a person of socialist or republican leanings such as myself could not help but admire the results.

However, the Opera was another matter. It was not to my taste. The style was so ornate, there was such a surfeit of sculpture and design, that the eye soon grew weary. It was cloying in the same way as Saint Peter’s in Rome, another example of excess and the determination to create the greatest specimen of its kind. Also, one need not see much of Paris before tiring of bronze female representations of la France, la Liberté, la Justice, la République, la Musique, la Poésie, all those sisters with the same formidably muscular bosoms and limbs, robes flowing, their stalwart faces uplifted to the heavens.

“I see you do not care for the grand style,” Holmes said. “Think, however, of the many artists and masons kept gainfully employed for so long.”

“Some of whom were second rate.”

“Nevertheless, the Paris Opera will endure long after we have shuffled off this mortal coil.” He opened his coat and withdrew his watch from his waistcoat. “Nine fifty-five, Henry. We shall judge something of the seriousness of this matter by the length of time we are kept waiting.”

Holmes was dressed formally: black overcoat, top hat, and frock coat, gray striped waistcoat and trousers, gold watch in one gloved hand, a fine walking stick with a silver handle in the other. As he was already tall, the top hat further added to his stature and made his nose appear smaller–imposing, rather than merely large. Having decided to play a subordinate part, I wore more casual garb, a tailored suit of heavy gray tweed.

Sherlock placed one hand on the massive iron door handle. “Behold the fatal portal. ‘Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’intrate.’”

“Dante, at the gates of Hell?”

“Yes. Come, Henry; we have our own fearful specter with whom to do battle.”

“‘Into the valley of death rode the six hundred.’”

Holmes grimaced. “Quoting bad Tennyson will surely irritate both the shade of Dante and that of the Opera, our mysterious ghost.”

Inside an attendant awaited us. “Monsieur Holmes? Ah, Messieurs Richard et Moncharmin vous attendent. Suivez-moi, s’il vous plaît.”

“Merci bien,” Holmes said.

Our footsteps echoed faintly as we went up that grandest of all grand stairways. Inside was the same abundance of sculpture, ornamentation and riches, with elaborate paintings on the dome high overhead. Again, the similarity to a church struck me. Once past the stairway, the interior had a certain labyrinthine quality; one could easily lose oneself in the Opera.

Messieurs Moncharmin and Richard awaited us in an office as grandiose as the rest of the edifice. Our interview was conducted in French and began with a round of facile introductions. Holmes had told me that Firmin Richard was a mediocre composer of martial airs. He was a large, burly man who seemed out of place in formal attire. Although his ruddy face was youthful, his hair and beard were white, his joviality forced. Armand Moncharmin was short and slight with a dandyish air. His frock coat, his cravat, his white cuffs were elegant and absolutely spotless. He wore a monocle in his left eye, and as he spoke, the waxed ends of his black mustache moved up and down.

“Eh bien, Monsieur Holmes, you have read our letter about this embarrassing business of the ghost.” For ghost he used the word revenant. “My partner and I are not superstitious. When we took over the Opera last October and the former managers, Messieurs Poligny and Debienne, told us about an opera ghost, we assumed this was a good-natured jest on their part.”

Richard smiled, but something cruel showed in the set of his mouth. “I enjoy a good trick myself, and I thought this was one.”

“However,” continued Moncharmin, “certain events have transpired which, while not completely convincing us that supernatural entities exist, do suggest some malevolent agency at work. Imagine our surprise when our predecessors showed us certain documents demanding payment of several thousand francs a month.”

Richard nodded curtly. “You English have a word, ‘blackmail,’ I believe.”

Holmes had sat drumming at the chair arm with the fingers of his right hand. “Documents? Where are these documents?”

Moncharmin handed him a thick stack of papers. “This is the complete contract between the Opera and the Government of France. On page thirty-seven is a list of four conditions which may cause the termination of the agreement.”

I leaned over so I could see the paper Holmes held. At the bottom, scrawled in red, was a fifth condition: “Or if said management delay beyond a fortnight the monthly payment of twenty-thousand francs to the Opera Ghost.” Here the word used was not revenant but Fantôme.

“Further on,” noted Holmes, “certain boxes are reserved for the President of the Republic and various ministers. Notice the addition on page ninety-two.”

In the same red scrawl had been added, “Box Five on the grand tier shall be reserved in perpetuity for the Opera Ghost.”

“Le Fantôme de l’Opéra,” Holmes said. “What remarkably crude and childish handwriting. This could not have been done with a regular pen, and the source of the ink is a mystery to me.”

I sat back in my chair. “Obviously it is meant to represent blood.”

Holmes raised one hand. “The intent is clear, but actual blood would be brownish.”

“I know that. I am a physician.”

Moncharmin laughed nervously, a flowing sound which recalled a harp too tightly strung. “It is a relief to hear you say that it is not real blood. We could not help but wonder...”

“Are there other amendments, Monsieur Moncharmin? No. Well, thus far this does resemble the common garden variety of blackmail, although the request for a box is curious.”

“As I said, Monsieur Holmes, we assumed this was a joke. However, since then, so many odd occurrences have happened that...”

“Such as?”

“Some are rather trivial. The principal white horse, César, has disappeared.”

“A horse?” I said.

Richard nodded. “The opera has a stable of ten. This one starred recently in Meyerbeer’s Le Prophète.

“There have been difficulties with Box Five. At first, the superstitious old woman who acted as box keeper, a Madame Giry, kept it vacant. When we discovered this, we dismissed her. She seemed to consider the ghost her employer rather than us. However, after several disturbances, we have again left Box Five vacant. Its occupants complained of mysterious voices and laughter, hardly conducive to watching a performance. Our patrons’ well-being is always a major concern. And now, one of our employees, Monsieur Buquet, has been... been... deceased.”

Holmes frowned, whether at the fact or the twisted syntax I was not sure. “How did he die?”

Moncharmin flinched at the word “die.” Richard said, “We think he hanged himself. He was found in the third cellar near a scene from Le Roi de Lahore. Most people think the Phantom murdered him.”

“Did the police not look into this matter?”

Richard and Moncharmin again eyed each other. Moncharmin managed a tepid smile. “Their determination was that it was suicide. The whole business was most embarrassing, and if not handled with great delicacy, could have affected box rentals very adversely. We understand, Monsieur Holmes, that you can be relied upon for discretion, and we hope...”

Holmes had been drumming at the chair arm again. “I do not speak with newspaper reporters, and I keep everything completely confidential. In return, I require the utmost frankness from my clients. I will tolerate nothing less than the absolute truth.”

The managers regarded each other again, then Moncharmin laughed weakly. “Of course, Monsieur Holmes. That goes without saying. There have also been... letters.”

Holmes sat up. “Let me see them.”