Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

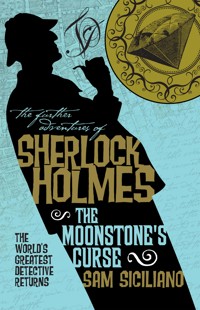

A mysterious gypsy places a cruel curse on the guests at a ball. When terrible misfortunes begin to befall some of those guests, Mr.Donald Wheelwright engages Sherlock Holmes to fin out what really happened that night. With the help of his cousin Dr. Henry Vernier and Henry's wife Michelle, Holmes endeavors to save Wheelwright and his beautiful wife Violet from the devastating curse.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 586

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AVAILABLE NOW FROM TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES SERIES:

THE ECTOPLASMIC MAN

Daniel Stashower

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS

Manley Wade Wellman & Wade Wellman

THE SCROLL OF THE DEAD

David Stuart Davies

THE STALWART COMPANIONS

H. Paul Jeffers

THE VEILED DETECTIVE

David Stuart Davies

THE MAN FROM HELL

Barrie Roberts

SÉANCE FOR A VAMPIRE

Fred Saberhagen

THE SEVENTH BULLET

Daniel D. Victor

THE WHITECHAPEL HORRORS

Edward B. Hanna

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HOLMES

Loren D. Estleman

THE GIANT RAT OF SUMATRA

Richard L. Boyer

THE ANGEL OF THE OPERA

Sam Siciliano

THE PEERLESS PEER

Philip José Farmer

THE STAR OF INDIA

Carole Buggé

THE TITANIC TRAGEDY

William Seil

The

further

adventures of

SHERLOCKHOLMES

THE WEB WEAVER

SAM SICILIANO

TITAN BOOKS

THE FURTHER ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

THE WEB WEAVER

Print edition ISBN: 9780857686985

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857686992

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St

London

SE1 0UP

First edition: January 2012

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2012 Sam Siciliano

Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address. To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive Titan offers online, please register as a member by clicking the ‘sign up’ button on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed in the USA.

To my wife, Mary, for many years of love, companionship and support. I can’t imagine that time without you. None of my novels would have been the same, if they even existed—especially this one.

Contents

Preface

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Afterword

Preface

Dear Reader,

As I mentioned in the preface to an earlier book, the death of my cousin Sherlock Holmes released me from a vow of silence; thus I could relate his exploits at the Paris Opera in what I felt was his most bizarre case. As I also noted in my earlier preface, I offered my writings as a corrective to John Watson’s distorted portrayal of Holmes. Watson and I were never on good terms, nor (his writings to the contrary) was he Holmes’ eternal bosom companion.

I was involved in other interesting adventures with Holmes, but the case I am about to present offers unique insight into my cousin’s character. Because of its intimate and personal nature, I debated long and hard before taking pen to paper. I am not one who believes celebrated people, dead or alive, lose all right to privacy.

However, my wife Michelle at last persuaded me that the story should be told and that we two were the only persons who might tell it fairly and completely. She could not bear that my cousin should be remembered as an unflinching misogynist—and a cold-blooded one at that. The passionate side of his nature was not restricted to music, and a certain woman was much more important to him than any other. Watson to the contrary, Irene Adler was most definitely not “the woman.”

My wife Michelle and I have both passed our eightieth year, and we decided it would be tempting the Reaper to delay any longer. Although the events described herein occurred nearly fifty years ago, they are still fresh in our minds. Both Michelle and I also kept extensive journals. Since our involvement was often separate—I frequently accompanied Holmes, while Michelle was with the woman in question—we decided to divide our tale. Thus you will find that Michelle narrates certain chapters, while I narrate others.

There is one other matter I must briefly touch on. Nothing like the story you are about to read could ever have appeared in print during the time it took place, early in the 1890s. It would have been considered outrageous and immoral. Although the queen’s long reign was nearing its end, “Victorianism” was in full flower. If writers dealt with prostitution, adultery, or divorce, it was only in the most hackneyed and conventional terms. All too many people—including many physicians—took their cue from the celebrated Dr. Acton and honestly thought that women had no sexual feelings, men were by nature lustful brutes, and the marriage act was a necessary evil for the propagation of the species.

Although the current generation always seems to think it has invented sin (especially sins of a sexual nature), one need only visit the cinema with its scantily clad females and suggestive dialogue to see that something has changed in the last fifty years. As an old man, I should bemoan the passing of the good old days and the good old morality, but I do not. Michelle and I saw, first-hand, too much misery caused by sheer ignorance of basic human biology and emotions.

Certainly by modern standards, there is nothing salacious or indecent in my narrative. It is, in one sense, a rather simple story with tragic overtones. God is my witness that I would never deliberately discredit my cousin or injure his reputation. If anything, my narrative should show, once and for all, that Sherlock Holmes was not a mere automaton or collection of eccentricities, but a man whose heart was, in every way, the equal of his brain.

Dr. Henry Vernier

London, 1940

One

On a cool rainy afternoon in early October I decided to pay a visit to my cousin Sherlock Holmes. Having just visited an ailing patient who lived near 221B Baker Street, I was dressed most formally in a black frock coat and top hat, my medical bag held in my left hand, my umbrella in my right hand.

The long-suffering Mrs. Hudson smiled when she saw me. “Good day, Dr. Vernier. Please come in. Mr. Holmes has never been... tidy, but brace yourself.”

The thick, sweet odor of pipe tobacco filled the room, and the disorder was monumental, even worse than usual. Some problem must be under consideration. Stacks of newspapers and books covered nearly every surface, volumes large and small. Holmes himself sat on the sofa, pipe in hand, his gray eyes frowning down at the massive tome upon his lap. He wore his favorite dressing gown, an ancient one of faded purple wool.

“One moment only, Henry, and then I shall attend you.”

I nodded, then gave Mrs. Hudson a sympathetic smile as she took my hat and coat. A coal fire was going, and I stretched out my hands to warm them. I glanced at Holmes’ desk, stepped closer, and noticed that the newspaper was a notorious scandal sheet.

My eyes caught the merest suggestion of movement. Oddly enough, one end of the desk had been left clear, and a fly was buzzing faintly and trying to move across a triangular-shaped, opaque surface, which I soon discovered was a web. A spider appeared and ran down from the corner of the web and seized the fly, which buzzed more loudly and tried, in vain, to escape.

“Good Lord,” I murmured, taking a step back. I did not much care for insects and spiders. I wondered if it would be permissible to roll up one of the newspapers... “Sherlock, Mrs. Hudson has been remiss in her duties—there is a filthy spider on your desk.”

“Do not disturb her.”

“Mrs. Hudson?”

“No. The spider.”

“The spider? But surely...?”

Holmes slammed his book shut loudly. “Very well, Henry. You have my attention.” He stood and walked over to the desk. He seemed paler and thinner than the last time I had seen him. He withdrew a magnifying class from a niche in the desk and bent to peer at the spider. The frantic buzzing of the fly had begun to subside. “She has him nearly bound. Would you care to have a look?”

“No, thank you. I do not much care for spiders.”

“That is unfortunate. They are remarkable creatures.”

“Perhaps. How long has that one been there?”

Holmes drew in on his pipe and rubbed thoughtfully at his chin with the fingertips of his left hand. “Almost a year.”

“Almost a year?”

A smile pulled at his lips. “You seem to doubt your hearing today. It has been a battle royal. Mrs. Hudson has most definitely not been remiss in her duties. She takes this innocent creature here to be the very symbol of the encroaching filth that God put women such as her on this earth to destroy. Our war, too, has lasted over a year. At first she asked me daily if she could not remove the vermin. Despite my instructions, I think she would have killed the spider long ago had I not threatened to seek other lodgings should she do so. I have told her that other spiders are fair game to her broom or dust mop, all save this one.” My perplexed expression made him laugh. “Come, Henry—have you never had a pet?”

“You know we have Victoria.” Victoria was our cat whom Michelle had most irreverently named.

“Then consider this small carnivore my pet. She is a prime specimen of tegenaria civilis, the common British house spider. She is a lady of great courage and determination, as well she must be to survive the undeserved hatred and abomination of the female of our species.”

“Not only the female!”

“As a physician, you should know that the fly is the great enemy of mankind. The fly is the carrier of infection and disease. The spider is our ally. Do have a look at her.”

Unenthusiastically I took the glass. The spider seemed immense, small hairs coverings its legs, spots covering its back. The fly was half smothered in silk, yet it still shook periodically, and I heard a faint buzz.

“Disgusting.” I set down the glass and turned away from the desk, hoping to steer us away from the spider.

Holmes smiled briefly. “I had no idea you were so fond of flies.”

“I am not fond of flies!”

This made him laugh. “Come, let us sit down. You need not watch her devour her prey.” I sat in one of the armchairs near the fire, while Holmes took the other and crossed his legs. “You look the very model of a prosperous physician today, Henry. And how is Michelle?”

“Now there you have the prosperous physician. Luckily avarice is stronger in my disposition than male pride. Her practice is thriving, and she makes far more money than I. Several women of the upper class have discovered that they prefer a woman physician, and she has become quite the rage. She will soon have to begin turning away patients. Only last week she snared Lady Connely. Old Thurswell must be furious. He has preached against women doctors for years. To have his wealthiest patient snatched away by a female half his age... It is rather delightful.”

Holmes laughed. “Come, Henry, you make her sound like my friend tegenaria civilis with her fly. I am glad to hear you are both prospering. What of her work with the less fortunate?”

“She would turn away Lady Connely first. She has made a vow that for each rich patient she takes on, she will have a poor one in the balance. We both still work at the clinic weekly.”

“I wish all physicians shared your charitable sentiments.”

“And you, Sherlock—what is all this? It does seem a bit... messier than...” A gesture with my hand took in the books and papers scattered about.

“I have been working on a puzzle, a very curious one.” He sat back in the chair and exhaled a cloud of smoke. “Tell me, Henry, did you ever read Watson’s story, The Final Problem?”

“Given your attitude toward his stories, I have always scrupulously avoided them. Is that not the one, however, where you die at the end?”

Holmes was amused. “Yes. At the Reichenbach Falls. And have you heard of Moriarty, Professor Moriarty?”

“No, I have not.”

“He is my arch-enemy, the Napoleon of crime, Watson has me calling him.”

“Does this Moriarty have any basis in reality?”

Holmes set down his pipe and leaned forward, his eyes suddenly bright. “Ah, that is the question—that is the puzzle. Even a week or two ago I would have told you he was a complete fiction. I would have been adamant. Watson’s stories to the contrary, most crimes and criminals are stupid. Only very rarely does a man of first-rate intelligence turn to crime. Most often we have only drunken ruffians or groups of them who bash in someone’s head, snatch a purse, or rob a bank. The true criminal genius is rare, and the notion of an evil mastermind behind the crime in London is a silly one. Watson has me comparing Moriarty to a huge spider at the center of an evil web sensing every motion, every criminal movement, in this great metropolis. Of course, I would never have come up with such an obviously preposterous metaphor.”

“Why preposterous?”

Holmes shook his head. “You know nothing about spiders either. Only a female spider can spin a web; only she sits waiting for her prey—and not necessarily at the center. If Moriarty were a woman, the metaphor might have made sense, but for a man, it is a foolish one.”

“Perhaps poetic license...”

“I do not take poetic license with the natural world! If Watson wished to make such an inane metaphor, he should have had it coming from his own mouth.” His face had grown quite red. “Pardon me. My irritation with Watson is only too ready to come to the surface. People are always comparing men to savage creatures such as wolves or spiders, but in reality, man is the only animal capable of true evil. There is no malice in the wolf or spider. I watched my spider devour her mate.”

“What?”

“Yes, she is one of the varieties which frequently consumes the male. The male is much smaller than the female. The female tegenaria will devour other spiders of either sex or even her own children after a certain age. It is curious how the roles of the sexes are reversed with spiders and humans. But I digress. I was telling you about Moriarty and the foolishness of the notion of a mastermind behind much of the crime in London.”

“Yes.”

“Unfortunately, I am no longer convinced it is so foolish an idea.”

His smile vanished, and as I stared into his gray eyes, I felt a kind of chill about the heart. “Good Lord,” I whispered.

“I am not certain, Henry. Perhaps I am wrong—I hope I am wrong.” He tried to draw on his pipe, but it had gone out. “Blast it.” He set down the pipe, stood, and walked to the large bow window overlooking Baker Street. “The past several months I have had a growing sense of... uneasiness. I thought at first it was only nerves, but now I think I had begun to sense a pattern, a shape—a web, if you will.” He glanced over at his desk. “Forgive me, tegenaria. Something is happening, I believe, but still it eludes me. It began only as an intuition, but I have been pondering the problem, reading over the papers for the past several months, checking certain leads, certain odd crimes. There may indeed be a Moriarty. It is ironic.” He laughed.

“What is?”

“If it were not for Watson’s preposterous creation, I might never have hit upon the idea. Two weeks ago I asked myself, what if there were a Moriarty? Only then did I begin to sense the pattern. So far I have no idea what kind of person he may be. If this pattern is real, then a major intellect, a truly imposing mind, is behind it. The design is intricate and very subtle. He is the opponent for whom I have always longed.”

I frowned. “How could you long for such a monster?”

“Have you never wanted to slay a dragon?”

“No, I can’t say that I have.”

Holmes leaned upon the windowsill, staring down at the street below. “Now what have we here? A visitor, if I am not mistaken. He would have given the cabby’s poor horse a workout. A little under eighteen stone, I would say. His clothes proclaim him a gentleman, but he has the physique of a boxer or stevedore. Ah, yes! He is at the door. I am tired of musing over insubstantial cobwebs, and it has been frightfully dull of late. Perhaps he has an interesting case for me.”

“I suppose I had better be going.”

“Not at all, Henry. You can play the part of Watson. Most of my clients expect to find him at my side. Besides, it is too early for supper. From what you told me of Michelle, she is probably engaged for the rest of the afternoon.”

“Yes, it is her day at the clinic. Very well, I shall stay. Medicine has also been rather dull of late. Let us hope your visitor has some interesting tale to relate.”

Holmes took off his dressing gown while he walked to his bedroom, and he returned wearing a frock coat, just as Mrs. Hudson appeared at the door: “Mr. Holmes, there is...”

“Yes, Mrs. Hudson, I know. You may send in Tiny.”

She rolled her brilliant blue eyes and withdrew.

Despite Holmes’ description, I was not prepared for the bulk of the man who entered, his head barely clearing the doorframe. He wore formal dress, the ubiquitous black frock coat, waistcoat with gold watch chain showing, and striped trousers, the toes of his boots shiny, but all in all, he did not appear at home in his grand apparel. He had a slightly frumpled look, his tie askew, an errant lock of hair almost standing up.

At one time, he must have been a superb physical specimen, but now, nearing forty, he had the look of a man in transition toward corpulence. His shoulders were still broad, but his waist was thick, his neck too fleshy and full under the square chin. All the same, at a good six and a half feet tall, with an eighteen-inch neck, fingers thick as sausages, and a weight nearer three-hundred than two-hundred pounds, he was an imposing figure. His hair and mustache were light brown, his eyes blue, his skin fair with a tendency toward redness. His gaze shifted from me, to my medical bag, to my cousin.

“Mr. Sherlock Holmes?”

“Yes. I am he. What may I do for you, Mr.—?”

“Wheelwright, Donald Wheelwright.” His immense paw briefly swallowed Holmes’ long, delicate fingers.

“This is my cousin, Mr. Wheelwright. As you noted, he is a physician.”

Wheelwright’s hand now swallowed mine. It felt sweaty, big, very strong, and I noticed the reddish-brown hair on the back. “Dr. Watson,” Wheelwright said softly.

I raised my eyebrows. Holmes’ gray eyes had a wicked gleam, and he turned Wheelwright aside before I could apprise him of my true identity. A very faint, floral scent touched my nostrils. I glanced at my hand and sniffed cautiously. Lavender?

“Now then, Mr. Wheelwright, do be seated and tell me how I can be of service.”

Wheelwright sat warily, and the chair was dwarfed with him in it. He gave a sigh, and his mouth stiffened. “I— This is a black business, Mr. Holmes. I usually like to keep my affairs private, but... My safety and my wife’s safety are at risk, and the police don’t seem to be of much use. I didn’t quite know where to turn, but I was told you were the very best for this type of deviltry. I’m not superstitious, mind you, but all the same...”

“Who has threatened you, Mr. Wheelwright?”

His eyes showed a sudden coldness. “Who told you I had been threatened?”

“You did, albeit in a roundabout manner.”

He nodded. “I see. Well, there have been letters, and... See here, did you ever hear about the business with the gypsy at Lord Harrington’s ball?”

Holmes’ fingers tapped at his leg, and he frowned. “Was that nearly two years ago?”

“Yes, that’s right. Two years in January it will be. You know about it then?”

“Only vaguely. Something about a gypsy curse, was it not? I saw a brief article in one of the papers. Tell me about it, Mr. Wheelwright.”

Wheelwright sighed and shifted restlessly in the chair, which creaked ominously. “She was— There was this old hag. She appeared during the dancing. This was the Paupers’ Ball, and we were all in costume. She told us we should be ashamed—as if having money was a fault—and then she said how wicked we were. She had a piercing voice that got a grip on you, and at first no one was quite sure whether she was part of the entertainment. She came down the stairs and cursed everyone and wished the most terrible things on us all. And then...” His mouth stiffened, his brow furrowed, and he shook his head. “It was not wise. My wife tried to talk to her. The gypsy began to shriek at her. Finally, Harrington’s servants seized the gypsy and threw her out. The party was spoilt, though.”

Holmes gave a sharp staccato laugh. “Yes, I’ll wager it was. What did the gypsy look like?”

“Like a gypsy.”

Holmes forced a smile. “And what does a gypsy look like? What did this particular gypsy look like?”

“An old hag, as I said, in a bright dress—red, I believe. She had a hooked nose and bad teeth. Oh, and she wore big round golden earrings. What an old witch.”

“But her voice was piercing rather than feeble?”

“Oh, yes. Everyone in the hall could hear her.”

“And your wife confronted her?”

He gave his head a shake. “She was across the room from me, or I’d have stopped her. You don’t try to reason with a lunatic.”

“And what did Mrs. Wheelwright say to the gypsy?”

“She told her that our being dressed up meant no... disrespect, and that only the Almighty could punish, and she even...” He drew in his breath. “She asked the old hag to pray with her for God’s mercy.”

“And the gypsy did not take kindly to these suggestions?”

“No, she was still cursing my wife as they dragged her off.”

“What exactly was the nature of these curses?”

Wheelwright’s tongue appeared briefly at the corner of his mouth. “That she and all she knew would have bad luck, and... die in torment, and...” His face lost some of its earlier ruddy color. “And that she—my wife—would be... barren.”

Holmes took his elbows off his knees and sat back. “And by barren did she mean childless?”

Wheelwright nodded slowly. “Yes.”

Holmes tapped at his knee with his fingertips. “I do not wish to appear insensitive, Mr. Wheelwright, but it must be asked. Do you and your wife have any children?”

Wheelwright’s eyes narrowed, a brief hint of ice showing in their blue depths. “No. My wife... she is... But it was not the blasted gypsy!” His neck grew redder. “We already knew, long, long before the ball... I said I’m not superstitious, and I’m not.”

Holmes nodded thoughtfully. “How long have you been married, sir?”

“Nearly eight years.” Wheelwright seemed to grudge each word.

“I see. So the gypsy cursed your wife in particular and everyone else at the party. How very dramatic. The newspaper article comes back to me now. The curse involved general ruin, misery and misfortune, lingering illness, and early death, I believe. A crowd of London’s high society mesmerized by a vengeful gypsy who appears out of nowhere at the ball. Somewhat like Poe’s ‘Red Death.’”

“What’s this red death? I don’t recall her saying anything about any red death.”

“I was alluding to the story by Edgar Allan Poe.”

“Who’s he?”

“An American writer of some note. But we digress, Mr. Wheelwright. Something more immediate than the ball has brought you to see me.”

“That’s right, Mr. Holmes.” His big hands formed fists. “Some strange things have happened to several of the people who were at the ball. Harrington himself cut his own throat. It’s enough to make a man nervous. And then... then there was this note...”

Holmes placed his hands upon his knees. “Note? Let me see it, please.”

“It’s... it’s not very... nice.”

“I must see it.”

Wheelwright sighed, then reached into the inside pocket of his frock coat. Holmes opened the brown, folded paper, read it, then handed it to me. The writing was a reddish-brown color resembling dried blood:

By now you know my curse was a true one. Your womb is all ashes and bitterness, and you will have no fruit. Perhaps I shall send the Master himself to claim you. You may burn every light in your home as brightly as can be, but it will not save you from Him. Let your foolish God try to protect you now! Watch out for the black dog, the crow and the spider, for they be my allies. Know that nothing you can do will possibly save you. No man, no power, on earth can help the pair of you. You are doomed. You shall soon meet me and the Master in Hell.

A.

I shook my head. “What deranged creature can have written this?”

Holmes took the paper and held it up to the light. “It, too, is very dramatic, and this appears to be real blood. The aged parchment is a nice touch. I can see why this might unsettle you and your wife, Mr. Wheelwright. Did it come in the post?”

“No. My wife found it one morning.”

“Where exactly?”

“In the library.”

“And how did your wife react to this hateful note?”

Wheelwright hesitated, then shrugged. “She’s not the hysterical sort, but she doesn’t much care for it.”

Holmes’ smile was close to a grimace. “Of course not.” He sat back in his chair and regarded Mr. Wheelwright through half-closed eyes. The big man shifted about in the chair uncomfortably. It was small for him.

“So you have been married nearly eight years?”

Wheelwright nodded. “That’s right.”

Holmes’ eyes were fixed on him. “And I suppose you are... fond of your wife.” I could not be sure, but I thought I heard irony in my cousin’s voice.

“Fond enough. See here, Mr. Holmes, I didn’t come here to have you ask questions about me and my wife. I want this gypsy business resolved, but leave me and my wife out of it.”

“That may hardly be possible given that you both seem to be at the center of the affair.”

“All the same, I won’t tolerate questions about my personal affairs. Violet—my wife—is my business and my business alone.”

“Yes, yes, Mr. Wheelwright. You do understand that I will have to extensively question her and your household staff.”

I sat up abruptly. “Excuse me.” Wheelwright gave me a look, which suggested he had forgotten I was in the room. “Your wife is Violet Wheelwright?”

He nodded.

“We have not met before, but my wife is her physician—and her friend, as well. In fact, they are engaged in some charitable actions together today, if I am not mistaken.”

Wheelwright frowned slightly. “The lady doctor is your wife? But she has some French-sounding surname, not Watson.”

“I must clear up a misapprehension, sir. I am not Dr. Watson.” Holmes, I could see, was amused. “I am Dr. Henry Vernier. My wife is Dr. Michelle Doudet. She uses both our names: Doudet Vernier.”

“Ah yes, I forgot to mention Henry’s name, did I not? Now then, when may I question your household, Mr. Wheelwright?”

“Soon, Mr. Holmes.” He withdrew an ornate golden watch from his waistcoat pocket and opened it. “I’m afraid I must leave. I have other business. I shall send word.” He stood up and glanced about the room, obviously displeased with its untidiness.

Holmes also stood. “There is the matter of my fee.”

“I shall pay whatever you wish. Will five hundred pounds be enough of an advance?”

I was impressed, but Holmes nodded politely. “That will do nicely.”

“I have my checkbook. If you have a pen...” He started for the desk.

“You need not pay me now, Mr. Wheelwright. I only...”

Wheelwright had almost reached the desk when he suddenly turned and dashed back behind the chair, moving remarkably quickly for so large a man. His blue eyes were wild, his face very pale. He raised his hand and pointed his thick forefinger at the desk. “Kill it!”

I took a hesitant step toward him. “Are you well, sir?”

“Kill it. Take one of those papers and kill it!” His hand began to shake as he lowered it.

Puzzled, I gazed at Holmes.

“I am sorry to have alarmed you, Mr. Wheelwright. I shall dispose of the spider. You can send me a check later. I believe you said you had an engagement?”

Wheelwright kept his eyes fixed on the desk. “Yes, I do. You... you will be hearing from me, Mr. Holmes. You should... clean your desk.” He strode to the door, glanced behind him at the desk to make certain the spider was not pursuing him, then swiftly closed the door.

I shook my head and returned to my chair. “Your spider will cost you a client one of these days.”

Holmes also sat. “Elephants do not truly fear mice, but the relation in size is about the same with our Mr. Wheelwright and tegenaria. Perhaps I shall have to try to move her, if only for her own protection. Luckily he was too fearful to attempt to kill her himself. So, Henry, Michelle and Mrs. Wheelwright are friends, are they? And what is the lady like?”

“Not like her husband. She is of medium stature and slightly built, a brunette, a vivacious, amusing lady who is also quite beautiful. I would never have suspected such a husband.”

“What of her intellect?”

“She seems most intelligent. And Michelle is not generally fond of stupid women.”

Holmes gave a sharp laugh. “No.” He sighed and sat back in his chair. “I feared as much, but it does not surprise me.”

“Whatever are you saying?”

“It is regrettable she is married to such a man.”

“Come now, he may not have an impressive brain, but I am sure he is fond of her and a responsible husband.”

“No—no—no.” Holmes rose up in exasperation, then sat again. “Your responsible husband has just lolled away the afternoon with his mistress.”

I stared in disbelief. “What on earth are you talking about?”

“Henry, I begin to think you are as hopeless as Watson. Was it not obvious where Mr. Wheelwright had just been?”

“No.”

“Did you notice his dress?”

“He did seem... frumpled.”

“Exactly! One of his waistcoat buttons was unfastened, his tie was crooked, a button on his left boot undone, and his hair ruffled. Can you not surmise why?”

“Why?”

“Because he had been lying in bed with his mistress until the last minute. He then dressed in great haste and came to see us in his disordered state.”

I shook my head. “Perhaps he is just sloppy.”

“Did you notice the quality of his clothes and his watch? He is a rich man of business, and he would not make it through the day in so slovenly a state. To begin with, no valet of minimal competence would let his master out the door looking that way. Even if the man’s servants were incompetent, his colleagues would have discreetly mentioned that he might straighten his tie or button his waistcoat. He also smelled faintly of cheap perfume.”

I put my hand on my head. “I did smell something! Perhaps... perhaps he was with his wife.”

“Could you not tell from his manner that things are amiss between them? Besides, married people do not indulge themselves in the afternoon. That time of day is reserved for expensive harlots and their clientele.”

“Balderdash! That is simply not true.”

Holmes’ smile vanished, and he stared thoughtfully at me. “Is it not?”

“Well, I cannot speak for all respectable married couples, but... no, I think not.”

Holmes looked away, then scratched briefly at his chin. “I must defer to you on this, but you said his wife is with Michelle. Besides, I doubt his wife would use such foul perfume, not if she has any taste at all.”

I sighed wearily. I had only met Violet Wheelwright a few times, but I had liked her. Wheelwright, on the other hand... And if he were an adulterer, too... “I cannot believe it.”

“Henry, you should know how common such behavior is.”

“It may be common, but it is wrong. Blast it all, Violet is so pretty! Why would he trifle with a prostitute when he is married to a woman such as her?”

“Is that not also obvious? Because he is a dullard, Henry—a blockhead. Her beauty does not matter. He wants someone equally obtuse who will flutter her eyelids and tell him how handsome and clever he is. I doubt his wife would do that.”

I shook my head. “No.”

“Wheelwright seems a familiar name... Of course—Wheelwright’s Potted Meats! I’ll wager he’s that Wheelwright’s son and heir. The old man has a reputation for being shrewd and ruthless. I cannot picture the son maintaining the family empire. Perhaps there is an elder brother.”

“They are rich. Michelle commented on it, and Violet has been only too willing to purchase medicine, food, and clothing for the poor. You have put me in an awkward position, Sherlock.”

“In what way?”

“I do not like to keep secrets from Michelle, and what you have deduced about Mr. Wheelwright concerns her good friend. Should I tell Michelle, she may be similarly perplexed, but knowing her, she will want to tell Mrs. Wheelwright about her husband’s infidelity. Who knows what misery may then ensue?”

“Oh, nonsense.” Holmes crossed his legs, took his pipe, and began to cram tobacco into the bowl. “If Mrs. Wheelwright is anywhere near as intelligent as you claim, she already knows about her husband’s infidelity. In my experience, the wife usually knows about the mistress, and so long as the husband is discreet, not particularly abusive, and continues to make his income readily available, she does not much care.”

“What a horribly cynical viewpoint.”

“Marriage is the institution created for cynics, but do not blame me for your dilemma. Mr. Wheelwright is the guilty party. If he makes a habit of leaving his afternoon rendezvous in such disorder, then others must have remarked upon the fact. By the way, had you heard anything of this gypsy curse?”

“Not a word. That note was certainly vile. What do you make of it?”

Holmes drew in on the pipe. “Probably some discontented servant, nothing more. The whole business is far too melodramatic to be genuine. It reeks of artifice, of histrionics.”

“But what about the gypsy at the ball?”

“The author of the note probably has no relation to the gypsy, but that affair also seems suspicious. An old gypsy cursing all of well-to-do London is simply too dramatic, too sensational. I always suspect reports of anything even faintly supernatural, and this is very dubious. I shall be interested in meeting Mrs. Wheelwright and hearing her version of the events. Wheelwright certainly has no flair for storytelling.”

“I think she will please you. She is remarkably beautiful, but her wit and liveliness are what captivate one.”

Holmes laughed. “You make her sound a very paragon. I suppose I must guard my heart, for she is, after all, a married woman.” His irony had a weary edge.

I sighed but said nothing. I could think of no rejoinder.

“Do not tell Michelle, Henry. I would not have her worried as well. Perhaps in this case, I should have kept my deductions to myself.”

He rose, glanced out the window, then walked to his desk and examined the spider with his glass. “Her meal is half gone. My poor tegenaria, you had another close call. Luckily the massive Mr. Wheelwright was too cowardly to strike you. Come, Henry, cheer up. Would Michelle spare you this evening? I am tired and have not dined out in a while. A good piece of beef at Simpson’s would be the very thing. Given Mr. Wheelwright’s promised check, I can afford to be generous and feed an industrious physician.”

I forced a smile. “Oh, very well. Michelle may be late herself since she is with Mrs. Wheelwright.”

“Good. It is settled then. Wheelwright, gypsy curses, and my mysterious Moriarty and his web will be forgotten for the rest of the evening.”

“You must tell me more about Moriarty.”

“In due time I shall, but not tonight—tonight, British roast beef shall rule supreme, and only topics conducive to good digestion will be discussed.”

Two

As usual, by late Wednesday afternoon, I was weary in body and soul. In the morning Violet, her footman Collins, and I had walked about and visited the patients who were too ill to come to the clinic. I was fairly well known as the lady doctor, but Collins provided security in so rough a neighborhood. A big, tall, strapping fellow with a ready smile, he was known to be good with his fists.

We trudged up many dark narrow flights of stairs which stunk of human waste and visited the cold, dimly lit rooms where entire families dwelt, squalor and misery their perpetual companions. The weather had recently changed, the golden warmth of early fall giving way to the foul yellow fog and drizzle which were harbingers of winter. I dreaded the change because I knew what would happen to so many of my patients. With the bell of my stethoscope pressed against their chests, I could hear the consumption devouring their lungs. Suggesting a change of climate, wintering over in Italy or Spain, would have been a cruel mockery to those who could afford neither adequate nutrition nor shelter. Many would not live to see another summer.

At the clinic, in the afternoon, the parade of human suffering continued. I saw many children and infants with runny noses, coughs and fevers. If they were lucky, it was only a head cold or the first croup of the season. The weather had also aggravated the rheumatism of the elderly.

One woman about my age (just past thirty) had the most beautiful chestnut hair. She also had a dreadful black eye and a split lip. “It hurts when I breathe,” she said. I had her disrobe to the waist so I could examine her. Her skin was very pale, truly almost white, her frame slender. The outline of the humerus showed through her skin, and the shape of each curving rib was clearly defined. Her fingers were long and thin, the bones prominent—an artist’s hands—but red and rough from toil. She was frail and beautiful; somehow she reminded me of a painting of Saint Sebastian stuck full of arrows. From her sagging breasts and slightly swayed back, I could tell that she had borne children, and the proof—a small pale girl with the same chestnut hair—waited beyond the screen.

On her left side was a fist-sized bruise, its bluish-purple contrasting with her fair skin. I drew in my breath. Behind me Violet muttered, “Dear God.” The woman’s face grew even paler.

I tried to probe gently, but soon tears streaked her cheeks. However, she made no sound. Half naked, she seemed so weak and vulnerable that it was hard to understand how any man could have hurt her so.

“I’m afraid you have some broken ribs, my dear.” I taped them up carefully and told her to come back to see me in two weeks time.

While she finished dressing, I turned to Violet. She had gone to the window, and now stood with her back to me, staring out at the street below. The pale nape of her neck showed under the long black hair that had been carefully wound about and pinned up.

“How are you?”

She said nothing.

“Violet?” I put my hand on her arm and felt, briefly, her muscles trembling violently, but then she slipped away and turned to face me. Her brown eyes had an odd glint—fear or rage, I could not tell which. She held her head very stiffly, but high and proud. She had the longest, most slender neck of any woman I knew. Her nose was also long and thin—aquiline—the nose of an aristocrat.

“I am perfectly well, Michelle.”

“You do not appear perfectly well.”

Her eyes shifted toward the woman with the chestnut hair who was just leaving. “I suppose you see many such cases.”

“Far too many.”

She drew in her breath and clenched her fists; I could see her will asserting itself and bringing her under its control. “I wish I could send Collins to visit the drunken brute.”

“That would do little good. You would only provide me with yet another patient, and the waiting room is already overflowing. Besides, such women are often fiercely protective of their husbands. She may even love him.”

“Love? You dare to speak of love, when...” She drew herself up even straighter and now the rage made her eyes shine. “Oh, if I were only...” She seized her lower lip between her teeth. “Forgive me, Michelle. You have work to do.”

I smiled. “You have done quite well. This is, after all, your second full day out with me. Most of my friends cannot even last through a single morning.”

That was at about three o’clock, and I saw the last patient around half past five. Unfortunately, it was the type of case which never fails to upset me. The woman was barely twenty, her baby just six months old. The infant seemed half dead, his eyes glazed over, his limbs long and spindly; he resembled some plant raised in darkness, the long stems a desperate attempt to grow its way out of the dark and into the light.

“How many drops have you been giving this child?” My voice shook and I tried to regain my composure.

The girl’s eyes regarded me warily. “Drops?”

“Drops. What is it—laudanum?”

“I wouldn’t give ’im no laud’num or whatever. It’s only cordial.”

I sat back wearily on my desk. I did not believe in corsets, stays, bustles, and voluminous clothing, so it was fairly easy for me to do so. My head had begun to ache, and I kneaded my forehead briefly with my palm. “Godfrey’s Cordial, I suppose?”

The girl still regarded me warily, and with reason—a sudden urge came over me to slap her. She nodded reluctantly.

“I don’t suppose you know what an opiate is? No, of course not. Godfrey’s is only a weaker version of laudanum. If you keep doing this to your child... You might as well poison him outright and be done with it.”

Her eyes filled with tears, and she put her fist over her mouth. “Poison ’im?”

My anger drained away, leaving me both tired and sad. “I don’t mean to be cruel, but Godfrey’s is very bad for babies.”

“I ’ave to get my sewin’ work finished, and ’e just won’t keep quiet otherwise.”

I handed her a handkerchief. “Blow your nose, dear, and don’t cry. It will do no one any good.” She complied loudly. “Have you no relative or friend who could help care for the child during the day?”

She shook her head. “No one, ma’am.”

I sighed, then clenched my teeth. Violet seized my arm. “You look so weary.” She took her purse and turned sternly to the girl. “You must work, I suppose, so that you and your child can live?”

The girl nodded again. “Yes, ma’am.”

“If you did not have to work, would you promise not to give the baby Godfrey’s Cordial?”

She thrust her jaw forward. “But I ’ave to work.”

Violet took a gold sovereign from her purse. “Not necessarily. This should get you by for a while, and if the baby is better I will give you another, then another.” The girl stared in amazement at the coin. “Will you promise me?”

The girl again put her fist over her mouth, then nodded.

“Take it, then.”

The girl clenched her fist about the coin, then clamped her hand over her chest. She stared at Violet in disbelief as if an angel had suddenly appeared before her.

“Bring him here in a month, and if he is better, you will have another coin. The doctor will see to it.”

The girl nodded wildly. “Yes, ma’am.” She put the coin in her tiny purse, then took the baby, who had hardly moved.

“Wait,” I said. “You must stop the Godfrey’s only gradually.”

I gave her instructions on how to taper off the dose and had her repeat them. She stammered them out, then curtsied first to me, then Violet. “Thank you, ma’am. Bless you for savin’ me and my babe.”

Violet would not seem to look at her. “Remember your promise.”

“Oh, I will, ma’am—I swear.” She turned, slid aside the cloth curtain of the screen, and departed.

I sat down on my desk once more. “I too thank you, Violet. I have often thought... If only I could hand out fistfuls of money, more of my patients would live. I don’t know what to do with such cases. They make me so... angry. Angry at everyone—the stupid girls, their wretched employers, our proud, self-righteous countrymen... Pardon me, I know it is late for the soapbox. Why do you not sit down for a moment? I think we are actually finished for the day.”

Violet stared longingly at the chair. “Perhaps I shall, but only for a moment. My corset is so tightly laced I fear I cannot both breath and sit simultaneously.”

“I warned you to wear your stays loose.”

“But then I would need a new wardrobe because none of my dresses would fit. Alas, Dame Fashion is a stern mistress. We of the gentler sex must keep ourselves ever beautiful, must we not?”

She said it so gravely, that I gave her an incredulous stare. She began to laugh in earnest. “The look you gave me! Oh, now I shall never be able to sit.”

I also began to laugh. Our laughter had a certain frayed, lunatic edge to it. We had passed a very long day together.

The curtain opened, and a hesitant face appeared. Blonde curls showed under the volunteer nurse’s cap, as well as rosy cheeks and blue eyes. The face radiated youth, health and eagerness, a combination all my poor patients lacked.

“Dr. Doudet Vernier?”

“Yes, Jenny?”

“Is everything... well?”

“Oh, yes. Violet and I were only... We are fine. Are we finished?”

“Yes, Doctor.”

“Good.” I stood up and set my stethoscope on the desk.

Jenny was watching me carefully, the hint of a frown showing on her broad, smooth forehead. Her father was a well-to-do merchant who sold fine china and silverware, a proud man who had not forgotten his humble origins and who did not aspire to social snobbery. His wife was a bit insipid for my taste, but Jenny was both intelligent and good-hearted. I had met her at a party six months ago and casually discussed the clinic with her. Next week and every week since, she had come to the clinic on my day there. We had talked about women and the medical profession on several occasions. Jenny was very shy, but I had tried to encourage her to consider becoming a physician. She was to be married in a few months, and I hoped her husband would not be the type to lock his wife up in the castle tower. Obviously she wanted to ask me something.

“What is it, Jenny?”

She stared at me gravely, licked her lips, but said nothing.

“Come, my dear, what is it? You can tell me.”

“It is something... of a personal nature, Dr. Doudet Vernier.”

“Yes?”

She gazed past me at Violet who was taking off the white apron which all the nurses and volunteers wore. Violet raised only her right eyebrow—a feat I had always envied. “I shall tell Collins to have the carriage brought round.”

“I shall not be long, I think.” I gave Jenny a questioning look.

She shook her head. “No, Dr. Doudet Vernier.”

Violet closed the curtain behind her, and I sat wearily on the wooden chair by the examining table. “Jenny, we have known each other long enough and our ages are near enough that you could call me Michelle. Dr. Doudet Vernier seems too formidable coming from you.”

Her eyes widened. “Oh, I couldn’t do that!”

“Whatever you are comfortable with. Now, what do you wish to talk about?”

She licked her lips again, and then spoke so softly her voice was quiet as a whisper. “I am to be married soon I think you know.” She stopped speaking. Her naturally rosy complexion grew even redder, a slow flushing spreading from about her ears.

“Yes, I know.”

“Well, I only... I wondered... I...” Her jaw seemed to lock, and she turned away abruptly. “I think I must leave.”

Comprehension dawned—I had seen these symptoms before; I knew both the cause and the cure. “Wait.” I smiled, stood, and seized her wrist. Her face was positively scarlet. “Has your mother told you nothing, then?”

“Only...” She shook her head. “Nothing.”

Not only insipid, but thoughtless. I drew in my breath. For better or worse, I was long past false modesty. “And you want to know what makes a man and woman, husband and wife?”

“Yes.” Embarrassed she might be, but her sense of relief was palpable.

“I shall tell you, and you certainly should know before you are married.”

“Oh, I think so, too,”

I hesitated for a moment. The biology was straightforward enough, but that was never all there was to it. “What is your young man’s name, Jenny?”

“Henry.”

I laughed. “What a dreadful name!” She immediately appeared stricken. “Oh, forgive me—that is my husband’s name. Teasing is a habit with me. And are you fond of him?” She nodded gravely. “Your father gave you some say in this matter?”

“He did.”

“And is Henry agreeable to look at?”

She gave a quick nod.

“More than agreeable?” Now she smiled, and her smile told me a great deal. “And do you think he cares for you?” Again she nodded. “And does he respect you?”

“I believe he does.”

“Then I think everything will go well.” I sighed, praying it would be so. So many things could go wrong. If the man were rough and insistent, the wedding night could be disastrous. I caught a glimpse of impatience in Jenny’s eyes, and I laughed. “Forgive me, Jenny. I shan’t be evasive. Let me explain.” And so I did, briefly and directly, as I watched Jenny closely. When I finished she stood staring at the window.

“How very odd. My mother only said... Is it not... something of an ordeal?”

I could not restrain a laugh. “Oh no, my dear. No, no. Perhaps at first it might be somewhat painful, but if you love one another and are patient with one another... It is most definitely not an ordeal—never let anyone persuade you of that, although many will try. A famous doctor has written that most women have no sexual desires whatsoever. That is utter nonsense. Some may have such feelings killed off by cruelty, indifference, or sickness, but when everything is right—when a man and woman truly love one another and consummate that love—it is the closest we ever come to heaven on this poor earth.”

Jenny’s cheeks were flushed, and now my own face felt hot. “Pardon me for being so blunt, but...” Jenny seized my big hand in hers. “Oh, thank you, Michelle—thank you!” She smiled at me. I laughed, and put my arm about her.

Someone brushed against the curtain, and it slid open. Violet had seized the cloth with both hands, her slender frame swaying. Her face was ashen, her mouth half open, her eyes wild.

Suddenly her legs gave way, and down she went, pulling the curtain with her as she fell. Jenny cried out. I went to Violet’s side at once. Her face was absolutely white, her lips almost blue, and she felt icy to the touch. Perhaps it was a seizure, but there was no muscle tension or spasm. She gasped for air and groped for my hand.

“I cannot... breathe.”

“Is she all right?” Jenny murmured.

“Get me some water,” I asked Jenny.

“Oh God,” Violet sobbed.

I rolled her over and started to unfasten her dress. I have large fingers, nothing dainty about them and, growing impatient with the endless row of hooks, I seized both sides of the dress and tore it open. When I saw the knot on her corset, I said a very vulgar word.

“Will she die?” Jenny asked.

“No. Not today. Hand me the scalpel from the table, would you? Careful now—it’s sharp.” I took the blade, cut through the knot, and then began to loosen the laces. “No wonder you can’t breathe. Oh, Violet, I thought you knew better.” I sat her up and took the glass from Jenny. “Have a drink.”

She took a big swallow, then drew in a deep breath. “Oh, thank you.” Her color had begun to return. She took her lip between her teeth, glanced at me, then away. “Oh, I feel such a fool, such a silly fool.”

She started to get up, but I grasped her shoulders. “Do not try to stand, not quite yet. Take a few more deep breaths. Does anything hurt?”

“I am fine, Michelle. You were quite right about loose clothing. My stays were far too tight. I could feel the whalebone and steel cutting into my flesh. Perhaps I shall throw out all my corsets.”

“Whalebone is truly the bane of womankind,” I said. Violet smiled, and I heard Jenny suppress a laugh. “Let me help you up. Are you certain you...?”

“I am well, Michelle. I only feel as if I were a very idiot.”

Jenny helped me get Violet to her feet. “Sit on the table for a minute,” I said. “I want to check your heart and your lungs.”

“Michelle—honestly, I am perfectly well.”

“I insist.” My voice had assumed its resolute physician’s tone. “Slip out of the sleeves of your dress.” I warmed the bell of my stethoscope with my hand and put it on her sternum. “Take a deep breath.”

I listened carefully, then took her wrist between my thumb and finger and checked her pulse.

Violet held her head high, her lips pursed in a half-mocking smile. “Tell me the truth, Doctor—will I live? Be honest with me. How long do I have?”

I closed my watch and put it away. “Everything appears normal. Provided you do not squash all your insides to mush with a corset, you should live to a ripe old age.”

Violet smiled and slipped her long white arm back into the blue silk sleeve of her dress.

I turned to Jenny. “Thank you for your help. We must continue our conversation another time. There are some things you should know which will make it easier for you.”

The rosy flush returned immediately. “Thank you again, Dr. Doudet Vernier.”

“I am flattered you are willing to confide in me, my dear. We women must help one another. And now I really hope my medical duties are finished for the day.”

Violet’s smile had faded away. She looked pale, her eyes curiously vacant. She slipped down off the table. “Can you fasten me up? And do my stays—but loosely.”

I frowned. “I’m afraid I have made a mess of things, but I did not want you to suffocate.” Since I had cut off most of the laces, I had to unthread the top part so I would have something to tie. “And half the hooks on your dress are gone. I don’t know how we shall get you decent again.”

Jenny said, “I know there are some safety pins.”

“Oh, do get them.” I shook my head. “I think you would actually have more room in the dress without the corset.”

“I stand before you a convert. Remove it, Michelle.”

I pulled out the laces, then with some effort, slipped her corset out of the dress and folded up the hard, nasty thing. Jenny returned, and she held the dress together while I pinned it. When I had finished, I stepped back and nodded at Jenny. “Not half bad.”

“I wouldn’t try to bend over,” Jenny said, most seriously. But then a laugh slipped out.

“I shall be wearing a coat over the dress, so decency will be maintained,” said Violet. “Collins and the coachman must have given me up for lost. Please, let us go. Jenny, we shall give you a ride home.”

“Oh, I can take a cab.”

“No, no. You and Michelle have saved me from a hideous death. A ride home is the least I owe you. Come, gracious ladies, fellow angels of mercy—I am spent.”

I am worldly enough that the vulgar meaning of “spend” flashed through my mind. I gazed curiously at Violet, but she was unaware of the innuendo.

The old man who mopped the floors tipped his hat to us, his smile revealing several missing teeth. Next to him was the young constable who watched over the clinic. “Night, ladies,” they both said.

“Good night, Mr. Platt, Constable Owens,” I replied.

Outside it was drizzly, the air cold and heavy. The brick buildings across the street from the clinic were drab and dingy, the advertisements soiled or defamed, and the men on the street all wore dark shabby jackets and caps. Even the cobblestones seemed soiled. Violet’s carriage, a luxurious four-wheeler with the footman and driver up top, had recently been painted blue, green, and gold. It was magnificently out of place, and I was happy to see it. I was always glad to leave the clinic, and tonight I was exceptionally weary.

Collins jumped down, opened the door and pulled down the steps. His grin revealed a gap between his two upper front teeth. He was formally dressed, but was spared the wig, the eighteenth-century jacket, and buckle shoes, which some of the pretentious wealthy insisted upon.

“Sorry for the delay, Collins,” Violet said. “We were detained.”

I let Jenny go first, then followed. Collins, as I had noticed before, enjoyed viewing the backsides of ladies while assisting them into the carriage, but I did not begrudge him this simple pleasure.

Violet leaned out the window. “Tell Blaylock we shall be taking Miss Ludlow home first. Reynolds Street, I believe.”

The carriage swayed as Collins climbed back up, then we heard the crack of the whip and the clop of the horse’s hooves on the cobblestones. I sighed and sank back into the cushioned seats. I knew from experience that the carriage was very comfortable, its springs providing a gentle ride, and I briefly wished that I were alone so I could take a nap. It was a busy time of day; outside we heard other carriages and the cry of voices.

“So you have been a volunteer nurse for some six months,” Violet said to Jenny. “I admire your stamina. The work is difficult.”

“It must be done,” Jenny said. She was seated beside me, and I reached over and gave her hand a squeeze.

Violet smiled. “Ah, but most people are content to leave the work to others. And do you dream of being a physician like Michelle some day?”

I stared curiously at Jenny. Although it had taken considerable effort, I had avoided asking her that question. She was staring down at her hands: they held her gloves and were white, her fingers long and shapely. Most men would have claimed she was far too lovely to be “wasted” as a doctor.

“Perhaps. I do not know if I have the skills or the aptitude.”

I smiled and gave her hand another squeeze. “You would do very well.”

Violet had slouched back in the corner of the seat, and she regarded us through languid eyes. “And have you discussed this matter with your fiancé?”