Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Engelsdorfer Verlag

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

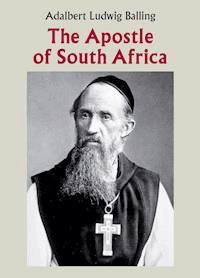

The Monastery of Mariannhill was governed by a man who combined German genius for leadership and German energy with a powerful and deep religious idealism. Dom Franz Pfanner looked like an Old Testament prophet. The eyes that burned in that long, aquiline countenance flamed like the eyes of a visionary, and the sensitive lips that quivered in that prophetic beard were ready to command no one knew what Crusades. (THOMAS MERTON about Abbot Francis Pfanner in The Waters of Siloe) - This book captivated me more with every page. Pfanner is filled with holy zeal for his »mission«. He is endowed with sheer inexhaustible energy and a marvellously open mind for innovations that was rare at the time. With his mosaic-style portrait the author strikes the core of this Apostle of South Africa. Many thanks for this enriching, interesting and exciting reading. It acquainted me with a fascinating personality. (REINHART URBAN, Director of Studies)

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 694

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Adalbert Ludwig Balling

THE APOSTLE OF SOUTH AFRICA

or God writes straight also with crooked lines

Francis Wendelin Pfanner An open-minded monk (1825–1909)

A Biographical Mosaic Portrait Of an “Adventurer in a Cowl” and an “Obedient Rebel”

Translation from the German original

ENGELSDORFER VERLAG LEIPZIG

“Der Apostel Südafrikas”

“The Apostle of South Africa”

First published in Germany in 2011

by Missionsverlag Mariannhill in Reimlingen

Bibliographical information by

German National Library:

Publication listed in German National Library

under “German National Biography”.

Detailed bibliographical information obtainable from

http://www.dnb.de.

ISBN 978-3-96008-125-8

Copyright © 2011/2015

by Adalbert Ludwig Balling

All rights reserved

Photographs: CMM-Archive, Rome/Reimlingen

English Edition printed by

Engelsdorfer Verlag Leipzig

Schongauer Straße 25, 04328 Leipzig

www.engelsdorfer-verlag.de

1st digital edition: Zeilenwert GmbH 2016

Content

Cover

Title

Map

Copyright

God’s Drummer

I. Langen-Hub near Bregenz

II. Parish Priest. Confessor to Sisters and Convicts

III. Pilgrimage to the Holy Land

IV. Mariawald Monastery

V. The Cross and the Crescent

VI. Daily Cares. Soliciting Vocations and Support

VII. Building Projects Completed

VIII. A Promotional Campaign with a Difference

IX. Opposition from all Sides

X. Years of Struggle

XI. The Eve of an Unknown Future

XII. If No One Goes, I Will

XIII. Setting Out to New Shores

XIV. In the Semi-Desert of Dunbrody

XV. Traveler Between Two Worlds

XVI. Preparing for the Great Trek

XVII. The Ricards vs. Pfanner Lawsuit

XVIII. Mariannhill flourishes

XIX. Mariannhill – Proto-Abbey in South Africa

XX. Mariannhill Pushes Boundaries

XXI. Monks or Missionaries?

XXII. Of Marriage, Schools and various Troubles

XXIII. Missionary Vigour

XXIV. The Monastery grows and grows

XXV. A Jubilee at Mariannhill. A General Chapter in Rome.

A Promotional Tour in Europa

XXVI. Strunk and Pfanner Clash

XXVII. Abbot emer. Francis does not Give Up

XXVIII. Emaus – United in Prayer

XXIX. Monk, Missionary and Hermit

XXX. New Abbot – New Rules

XXXI. The Founder’s Magical Repertoire: Old Ideas and New Propositions

XXXII. God’s Kingdom has no Boundaries

XXXIII. Friendly Letters from the Cape of Good Hope

XXXIV. Varia et Curiosa under the African Sky

XXXV. What is the Future? What the Solution?

XXXVI. The 81-year-old Abbot rallies

XXXVII. Trials and Sufferings

XXXVIII. In Franz Pfanner’s Footsteps

XXXIX. Epilogue & After Words

THE ABBOTS OF MARIANNHILL

Mariannhill Biographies

Footnotes

“Abbot Francis Pfanner died a saintly death.

He was a self-sacrificing monk, a missionary on fire to save souls and a successful organizer.

His only fault was to have believed that the Trappist contemplative life could be combined with the active life of a missionary.

He will go down in history as one of the most outstanding men in a long line of missionary heroes.

The Almighty chose to give him a heavy cross;

carrying it with fortitude, he became a saint.”1

God’s Drummer

A Man of the Hour – Apostle of the Zulus

“Live with your century, but do not be its creature!” was Friedrich Schiller‘s advice to his contemporaries. For Francis Wendelin Pfanner, an Austrian from the north-western part of Vorarlberg, the need to obey God was not in question. Neither did he doubt the value of qualities like commitment, valour or boldness. These enabled him to accomplish the goal he had set for himself: to advance the Kingdom of God in all circumstances and in the face of any resistance. He constantly asked himself: Is what I am trying to achieve God’s will, or am I simply seeking my own ego? Is it beneficial to others or are my wishes and expectations dictated by self-glory and the quest for approval?

In Wendelin Francis’ case, nothing at all and certainly not undue solicitude for his health and life, was allowed to stand between him and God. It will be seen that the “Apostle of the Zulus” was a non-conformist. No matter what his undertakings, his charism invariably made a powerful impression. He drew crowds of listeners and admirers wherever he went – to Tyrol, Carinthia, Vienna, Linz, Bavaria, Eastern Prussia, Silesia, Saxony, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Natal or other parts of South Africa. The vigour with which he “beat the drum for the missions” was unique. Wherever he appeared in public, people felt challenged. His enthusiasm was infectious; he swept his listeners off their feet. They realized that here was one who fought God’s battles, though his higher superiors or one or other church prelate might want to stop him. He was a man of the hour, a man of his times. Towards the end of his life he chafed under the cross God gave him. But when at the age of almost eighty-four he died, many contemporaries considered him a saint.

More than a hundred years after his death, we ask: What was so special about Wendelin Francis Pfanner? Why all the fuss about a contemplative monk, a Trappist whose rule “condemned him to lifelong silence”? Some answers come spontaneously: The monk and missionary Francis Wendelin put heart and soul into both his vocations; not only did he honour the Benedictine motto ora et labora (pray and work), but he also recognized the power of the press as an effective instrument for carrying on the work of evangelization and promoting religious and missionary vocations. Last but not least, he was known for his fervent devotion to the Sacred Heart, Christ’s Precious Blood and the Blessed Mother.

Abbot Francis Pfanner is righty credited with spearheading the evangelization of the Zulus. Therefore, he deserves to be called the Apostle of South Africa. He was an energetic advocate of the dignity of every man, woman and child, a champion of racial equality and a resounding voice calling for the Church to become socially engaged. He was the first to send African boys to Rome to study for the priesthood. But he was also, especially in his last years, a loyal monk, resigned to the Will of God and ready to accept and bear suffering, pain and sickness for God’s sake. This attitude of generous surrender made him a role model for many.

Why, we may ask today, was there so much reluctance to introduce a process of beatification for him? Was it because we expected him to be perfect before he died? Or was it because a process could be troublesome, or we, his sons and daughters, did not wish to be challenged by his saintliness?

The truth is that while a saint is still in-the-making, as it were, he/she is neither complete nor perfect. Candidates for sainthood are peoplein-progress like we are, pilgrims in via – on the way. Sinners who endeavor to be good, they know their own weakness and are humble about it. They fail but they also get up and try again. They surrender to God’s will and trust in the Holy Spirit’s guidance. Ultimately, God uses them to prove that He is quite capable of writing straight with the crooked lines of their lives, any life.

Dear Reader

It is not possible to sketch the life of Francis Wendelin Pfanner in several volumes, leave alone, in one. Neither can a sketch be produced with a few strokes of the pen. But it is possible, with the help of many strokes, many details, to compose a biographical mosaic – colourful, interesting and informative. This has been my aim in writing this book.

What you hold in hand is not a biography in the strict sense of the word. Why? Because this time I wish to approach the life and work of Abbot Francis Pfanner in a way that differs from my earlier approaches.

The life of “The Apostle of South Africa” may be compared to a colourful tapestry or a checkered quilt, which at times you may find probing and challenging. I hope that thread by thread and patch by patch, a portrait emerges which reflects the true identity and spirit of the extraordinary man Wendelin Francis Pfanner.

My almost exclusive source is a documentary work in four volumes of approximately a thousand pages each. It was compiled by Rev. Timotheus Kempf CMM in the 1970’s and 1980’s for private use by the Mariannhill Fathers, Brothers and Sisters. Its purpose was to enable an investigation into the life of the Founder in view of his eventual beatification and canonization.2 I have kept footnotes and other references to a minimum. My aim is to paint Pfanner’s portrait with the help of episodes, parables, essays, maxims and aphorisms in interview-style, here and there adding a short comment or selected testimony by a contemporary, in order to complete the portrait and make it colourful and attractive.

In short, I would like the reader to enjoy this book and personally meet the Founder of Mariannhill. – Note: “An Adventurer in a Cowl”. (5th ed.) is an abridged version of a biography of the Founder, published by Herder.3

I hope that in the end, the reader will agree with me, that the life of Wendelin Francis Pfanner is indeed many-sided and full of surprises. The direction it took seems improbable in parts; yet the story is very straightforward. The Portuguese proverb “God writes straight with crooked lines” applies to it like no other.

I thank you for your interest and wish you and your loved ones God’s blessing and the protection of his Holy Angels.

Adalbert Ludwig Balling

I. Langen-Hub near Bregenz

A lifelong Love of Home

Vorarlberg is an ancient cultural landscape. It has been settled since times immemorial. The Rhetians came before the Celts. The Romans, too, left their imprint. Bregenz (Brigantium) received its town charter from Emperor Claudius. The Christian religion entered the region on the heels of Roman imperial troops and colonists. Later, much later, with Emperor Constantine’s rise to power and the erection of the diocese of Chur (now Switzerland), Christians felt emboldened to come into the open. Chur was separated from the north Italian archdiocese of Milan and incorporated into the Frankish imperial church. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Vienna appeared on the map, and Vorarlberg was affiliated by imperial decree, not to Salzburg of greater Austria, but to the Diocese of Brixen in Tyrol.

Vorarlbergers are said to be warm hearted people who love their homeland and the religion of their ancestors, the Catholic religion. At the same time, they are known to be demanding, strict, intransigent and quick to defend themselves when their freedom and rights are contested.

Francis Wendelin Pfanner’s ancestors came from the Alemannic (Swabian) Allgau. He explained the family name “Pfanner” as deriving from “panner”, pan-maker. The family owned a farmstead, Langen-Hub, one of several others on the border with Germany. It was approximately a three-mile walk from the parochial village of Langen and not far from Bregenz, the capital of Vorarlberg.

According to the parish register, Wendelin’s father, Anton Pfanner, was born in 1794 and on 25 October 1822 married the twenty-two-yearold “virtuous maid”, Anna Maria Fink of Weissenhub. They had three sons and two daughters. Johann und his twin-brother Wendelin were born on 20 September 1825 and baptized on the same day at Langen. Godfather to red-haired Wendelin was his paternal uncle, Wendelin Pfanner, then a student of Theology, and his godmother, Magdalena Fink, a maternal aunt. His mother died of childbed fever at the age of twenty-six after giving birth to her fifth child, a girl, who also died!

For six years, the father’s sister Catherine took care of the Pfanner children. Wendelin and his siblings called her “Godle”, dialect for godmother. She was capable and by Abbot Francis’ testimony, a “strict foster mother: industrious, economical, responsible, devout and orderly”. She did not spare the “birch” or rod. Wendelin did not particularly like her cooking, but in his later years he fondly remembered her meatless dishes, usually fry-ups: spaetzle and noodles, fatless cheese and sauerkraut.

The Founder’s Memoirs give a glimpse of the family’s faith life.

“The unwritten law was: No day without morning prayer and no main meal without grace. Grace after the midday meal was followed by a string of prayers: several Our Father’s for a happy death and prayers to St. Martin and St. Wendelin, to guard the house against malice and accident; prayers for parents, relatives and the Holy Souls in Purgatory, and finally the Angelus. After the last grace at supper we all said an Our Father for the Holy Souls, a prayer for a good night, an act of contrition and a few ejaculatory prayers. All prayers were led by my father and joined by the farmhands.”

The house in Langen-Hub, Vorarlberg, where Pfanner was born

At the age of seven, the twins started their primary education in a oneroomed school house in Langen-Hub, where a teacher, who also functioned as organist and sacristan, taught Religion and Arithmetic. German (Grammar) was not a subject, “because people thought that it was enough for peasant children to know how to read and write”.

Wendelin was only eight years old when he had to get up at five every morning to help his parents in the stables, as was the custom in rural areas. The Pfanner children also had to give a hand with cutting and sawing logs, cultivating the soil, making hey, binding sheaves, harvesting potatoes, and erecting fences.

On Low Sunday 1833, the twins were allowed to make their first Holy Communion. They were confirmed on 19 June of the same year, either in the parochial church of Bregenz or at Feldkirch. A year and a half later, on 21 October 1834, Wendelin’s father married again. His second wife was Maria Anna Hoerburger (*1808) from Sulzberg in Bregenzer Wald. She gave birth to three sons and four daughters, of whom three died soon after birth.

One early morning when the sun was just up, Wendel was to drive a two-horse wagonload of sand to the mill. He failed miserably, as the wagon overturned and the sand was spilled. His father, watching him closely, ran up and snarled: “You will never be a farmer! I give you just one more chance: Try your luck in the saw mill! If you fail again, you will study!”

Studying in Feldkirch and Innsbruck

Abbot Francis relates that very early on Michaelmas Day (29 September 1838) his father came into the bedroom which he shared with his twin brother and shouted for him to get up!

“Wendelin! You must go to Feldkirch to study!” – I was awake immediately. On this morning, I put on a new student’s coat instead of my short jacket and exchanged my coarsely sewn and heavily cleated boots with a fine pair of thin leather shoes made for town. Thus duly apparelled, someone completed my outfit by shoving a fire red umbrella under my arm. When my father dipped his fingers into the Holy Water font by the door I did the same, but I remember that I did not know why my stepmother was crying and telling me to be good. – Once we reached the highway, my father pulled out his beads and on this beautiful morning we said a whole Psalter (15 decades) in turns. Later, we boarded a nice horse drawn omnibus which brought us to Feldkirch, City of the Muses … When my father left to return home, the only thing he said to me was: ‘Pray always and study hard’!”

Wendelin was soon known all over Feldkirch on account of his red hair. His record in the 1838/39 school registry is evidence of a good head: “Wendelin Pfanner – Conduct: Excellent; Social Studies, Religious Knowledge, Latin, Geography and History: Very Good; Arithmetic: satisfactory.” Because his first lodging was rather primitive, his godfather, now a parish priest, hired better quarters for him “at the house of two elderly ladies”. He attended daily Mass at the Capuchins’. However, after two and a half years he and a friend took up quarters with a lady and her two daughters who also boarded other students. With them he undertook hikes and weekend excursions. One evening, he found the front door at his landlady’s already locked. How could he get to his room without waking her? He quickly found a way: Making a desperate attempt to climb the leaning wall at the back of the house, he reached the open window of his room, jumped in and landed with not too much of a thud on the floor – only to find the landlady already standing in the door, shaking her head at him and saying but one word: “So, that’s how it’s done, eh?” He wished the floor had opened under his feet. Unable to utter a single word, he vowed to himself never to get into any more misconduct.

Later, a school friend remembered: “Wendelin and I had a room at Rev. Professor Wegeler’s. But after seeing under what circumstances the snuffing lady cook in the kitchen prepared our favourite dishes, we decided to leave the place as soon as the year was over.”

Wendelin spent his vacations at home, giving a hand with the work in the farm, woods, fields and sawmill. It was good exercise for him and a lot of fun besides teaching him many useful skills, as he gratefully remembered in later years.

At the end of September 1844, he and some of his classmates transferred to the Gymnasium in Innsbruck, the capital of Tyrol. The way there led across the Bavarian Allgau by way of Staufen, Immenstadt and Sonthofen (“Where my father bought our excellent Allgau bulls”) to Reutte in the Lech Valley. It was a journey which the Founder vividly remembered in 1901, when he was seventy-six years old:

“All my travels from Bregenz to Innsbruck and back were across mountains and hunchbacked hills … I remember that once on a late afternoon we got caught in a dense fog and suddenly found ourselves on the edge of a cliff over which a swift brook cascaded downward. The fog had lifted just enough for us to see the horrible depth to which this brook plunged. To add to our predicament, we had a classmate with us who was shortsighted and terribly frightened. Seeing the poor fellow quaking in his boots, I said to him: ‘If you care to entrust yourself to me, I will carry you down!’ He agreed, though very reluctantly. Quickly therefore, before he could change his mind, I swung him like a sheaf under my left arm and dragged him down – like a cat, her kittens – while with my right hand I groped down the sharp rocks. He closed his eyes, screamed and prayed but, thank God, did not resist. We made it down! Laying him on the grass, I ordered him to open his eyes and stand on his feet.”

Philosophical Studies in Innsbruck and Padua

In Innsbruck, Wendelin had excellent professors, all Jesuits. He studied Philosophy and graduated with honours. His final certificate, issued 31 July 1845, confirmed his “great diligence” in all subjects except Latin Philology, in which he managed a mere “diligent”. In Innsbruck he attended the daily Eucharist at the Chapel Royal “in the presence (portraits) of Emperor Maximilian and his iron clad ancestors”. Not long after he returned from his vacation for third-semester Philosophy, three of his classmates came to say good-bye. They were on their way to Padua to complete the semester at that famous university. Wendelin was much enticed but lacked the necessary funds to join them. Well, they said: “Volenti nil difficile! (Nothing is difficult for the determined.). They were right! In no time he found a family friend who was working in Innsbruck to lend him traveling fare and a little more. He instructed him to send the bill to his father and gave him a handwritten note to enclose with it saying that he, Wendelin, had gone to Padua for further studies.

That problem solved, he turned his face to the south – anxious with expectation. At the crack of dawn the following day the adventurers were gone, but not before Wendelin had left three guilders for his landlady and a farewell note: “Adieu! Here is my rent for the month; I am off to Italy!” Neither he nor his companions had visited Italy before, but they were willing to take a risk. Entrusting their luggage to a carrier, they hiked across the Brenner as far as Brixen and from there made their way to Italy by pay coach.

It was customary for Padua students to wear top hats, black tailcoats and, in that year, 1846, a “Pio-Nono-Beard”. 4Class conscious dandies strutted about the city in polished boots and, a Havana between their teeth, swung their “stylish swaggering canes”. The casual Mediterranean rhythm determined the life of the signori. “Most days the professors lectured to half empty benches … All we did in Philology was to translate ten pages of a Latin author into Italian.” Sometimes the “northern lights” from Vorarlberg were the only students attending demonstration classes in the theatre. They changed quarters several times and for different reasons, but in one place it was the landlady who complained that their hobnailed boots scratched up the marble floor of her pensione. Things were not exactly as they had expected; yet Padua did have its redeeming grace.

Abbot Francis:

“Though I came to Padua undecided about my career, I knew after one month that I would be a priest. As I observed the behaviour of the Italian students and got to know firsthand how depraved many of them were, no other but the celibate life held any more attraction for me. From that moment my eyes were set on Brixen, my bishop’s residence and the place of the diocesan seminary of Tyrol.”5

Padua had nothing further to offer to the Vorarlbergers. Though derided as “barbarians!” and “potato eaters!” their final certificates were the best the professors issued that year. They departed as quickly as possible, taking the train to Verona and continuing by coach to Lake Garda and Milan via Pavia. The last leg was done again by train as far as Lake Como. From there they went on foot across the Spluegen Pass and by mail coach past Liechtenstein to Feldkirch. At Langen-Hub, father and siblings were just bringing in the hay when Wendelin walked in the door. Happy to be home again, he willingly gave a hand. In fact, he spent his entire vacation, not with books, but with rake and pitchfork!

At the Brixen Seminary

The first year in Brixen, 1846 – 47, was a so-called “free year” with candidates attending lectures at the seminary but boarding on their own. Wendelin took his studies more seriously now. At the end of the first year he scored a “very good” in Church History under Professor Fessler and in Oriental Languages – Arabic, Syrian, Chaldean – under Professor Gasser, besides getting good passes in Biblical Archeology and Hebrew.

As soon as the students transferred to the seminary they received the clerical tonsure and the “short clerical cassock with tie”. Life now consisted of studies and offered very few diversions. Although there was a bowling alley and a beautiful garden to stroll around in, these pastimes did not provide enough exercise for one who had grown up on a farm in Vorarlberg. The view from his attic window was gorgeous but the mountains he could see were “out of bounds”. Too little exercise, cramped living space and a diet that was “far too greasy and devoid of fiber and vegetables” undermined his health. How could he remain fit? Wendelin took every opportunity to flex his muscles.

Abbot Francis:

“I remember that once during our common recreation my fellow seminarians wished to give themselves additional exercise by freehandedly standing up a tall pole with a handkerchief tied to its top. They could not do it. The few who tried fell on their faces, pole and all. But when they saw me coming they shouted: ‘Here comes Pfanner! He can do it! Just watch him!’ I needed no coaxing but simply picked up the pole, tied my cassock to it and with one jerk: ‘heave-ho!’ stood it up straight, while not moving an inch from my foothold … I venture to say that if there had been prizes for such feats, I would have fetched the first prize every time.”

Later, the Founder remarked that it was the unbalanced diet more than anything else that undermined his health. He came down with a heavy nosebleed and was diagnosed with pneumonia and an inflammation of the brain. Losing consciousness several times, he became so weak that the doctor sent him home to pick up new strength.

The following year, 1848/49, was rather quiet and uneventful. Or was it?

Abbot Francis:

“The only thing I vividly remember about my last year [before ordination] was that I suddenly felt a powerful urge to go to the missions. I also know what triggered it. It was the verse in the Miserere: Docebo iniquos vias tuas et impii ad te convertentur: ‘I will show your ways to the godless and sinners will return to you’. (Psalm 50:15), which we prayed every week. It haunted me until I confided the matter to my spiritual director and confessor. He submitted ‘my case’ for decision to the prince bishop. Before long, His Excellency ruled: ‘Oh, that Pfanner lad! He is not strong enough to go to America. He better stay at home.’ – In those days, at the mention of ‘mission’ and ‘unbelievers’ people understood America and nothing but America.”

The bishop had spoken and Wendelin stopped dreaming about the missions. Or did he? For the time being his mind turned to other pursuits. After successfully passing his finals he went on what he called “a pilgrimage to ‘Holy Cologne’.” – In the late middle ages, Cologne had been the most frequented place of pilgrimage after Jerusalem, Rome and Santiago de Compostella. Wendelin had collected enough money for the trip by saving his meagre allowance and cutting his fellow students’ hair. He deliberately denied himself “simple pleasures” for the greater pleasure of seeing a bit of the world and “travelling intelligently”, i. e., learning by seeing rather than reading.

His trip fell in the late summer of 1849. Setting out from Munich, he went via Augsburg, Nuernberg, Bamberg and Wuerzburg to Frankfurt/Main and from there via Coblenz and Bonn to Cologne. He kept his money – all in twenty-ducat coins – safely sewn in his red leather belt and carried his underwear in a backpack. The currency differed from one county or canton to another and so did the food. If, for example, he asked for a bun, he was “served a bun with butter”, although he would have preferred it dry as at home. But such was the custom. When in Rome, do as the Romans do.

The one thing he wished to see before anything else was the cathedral of Cologne with its two grand spires just then under construction. It was in Cologne where he, as president of the “Cologne Cathedral Building Society of Brixen”, delivered the contributions of his fellow seminarians. Then he took a closer look at the magnificent gothic structure.

Abbot Francis:

“I could not see enough of it! If only I could have taken the magnificent edifice with me!6 Construction had been interrupted for many years because the master plan had been misplaced, only to be found again much later in an attic in Darmstadt. I would have also visited Aachen and Brussels, if it had not been for a nasty footsore I had developed when climbing in the Tyrol Alps. Because of this sore I had to discard my boots and buy a pair of soft open shoes, the kind worn by ladies … Leaving Cologne, I travelled up the Rhine via Darmstadt and Worms to Speyer and from there to Heidelberg, Mannheim and Karlsruhe. I was lucky to be able to use one of the new railway lines as far as Freiburg.”

His next longer stop was Strassburg, and only after he had marvelled at all the wonderful sights that famous city offered did he continue his journey to Basel and from there via Lake Lucerne to Switzerland. Though he did not climb the Rigi – “because it was shrouded in mist” – he did visit Flueli7 and Einsiedeln Abbey, where he paid his respects to Our Lady, whom he asked “to help me become a good priest”. On he went on foot to the “delightful Lake Zurich” and from there to Schaffhausen to see “the Rhine Falls”. Passing Constance and Bregenz he arrived home just in time to help with the hay. “Pleased to see you after so many days,” his father welcomed him drily. “We have had nothing but rain so far. Much hey and grass is flat … You will have lots to share I should think but the stories must wait until Sunday!”

Once the harvest was in the barn, Wendelin had a few free days before he returned to Brixen for his final year of Theology. He had excellent professors: Fessler became Bishop of St. Poelten, Gasser, Prince Bishop of Brixen, while two others represented Austria at the Diet of Frankfurt (1848). At the Synod of Wuerzburg (also in 1848), his much esteemed teacher, the historian Dr. Gasser, was called the “living lexicon of Church History”.

Ordination and first Holy Mass

Wendelin was ordained sub-deacon on 14 July 1850, deacon, on 21 July, and priest, on 28 July – all by Prince Bishop Bernhard Galura, in the chapel of the Brixen seminary. Ten of the fifty seminarians ordained that years hailed from Vorarlberg! Soon after becoming a priest Wendelin traveled by horse carriage across the Brenner to Innsbruck and from there by postal coach via Reutte on the Bavarian border to Hindelang, where his father and the assistant priest of Langen waited to meet him. His first Mass was scheduled for 12 August at his home parish in Langen.

Abbot Francis:

“Very many of my relatives who lived scattered in different villages in the Bavarian Allgau came to Langen to welcome and congratulate their priest cousin, who was about to say his first Holy Mass. People in the Allgau consider a first Mass a particularly joyful event. The first thing these cousins and aunts of mine did was to kneel down to receive my blessing. People formed not just a procession but a triumphal parade, starting from the last village on Bavarian soil. Amid the crackling of small cannon and canopied by green triumphal arches I entered our homestead, people pressing in on me from all sides to wish me well. My mother stood with unconcealed pride in the doorway, ready to welcome me. She and my father knelt to receive my blessing, as also did my twin brother whom I had so often thrown into the grass during our boyish games in younger years. … My first Mass was a rare occasion for Langen, because the last such Mass had taken place fully twenty-five years earlier, when my priest uncle Wendelin had stood for the first time at the same altar as I. Now he and I celebrated together, he preaching the sermon.”

Before we follow the newly ordained priest to his first assignment, it may be well to pause for a brief review. It is based on the reminiscences which Fessler from Bregrenz, one of Wendelin’s classmates shared in 1888 on the occasion of their 25th anniversary of ordination. Fessler wrote:

“Pfanner was always serious about his studies. He excelled in Maths. I would like to illustrate his simplicity and self-control by referring to something he once said to us when we criticized a certain dish: ‘What does it matter how it is prepared as long as it is edible? Eat what is set before you!’ – While we were at the seminary, he was several times asked to mediate between rivalling friends and classmates. We came to appreciate his astute, practical mind, his clear vision and exquisite tact whenever he dealt with a sensitive issue.”

The editor of an 1888 commemorative brochure in honour of Abbot Francis expressed similar sentiments. According to him, the abbot was even as a youth known “to be diligent, industrious, solidly grounded in faith and morals, above board in every respect, opposed to evil in any shape and form, and fearless in expressing an opinion when it was called for. A good speaker and excellent mediator, he knew no regard for persons when he brought warring parties to terms. His faith was not shaken; neither did he change his mind once it was made up. Not given to making big or many words, he did study the theory of a proposition before he tabled it.”

II. Parish Priest. Confessor to Sisters and Convicts

Pastoral Ministry in Vorarlberg, Confessor in Croatia

Four weeks after celebrating his first Mass, the new priest Wendelin Pfanner entered the pastoral ministry in Haselstauden near Dornbirn, Vorarlberg. Not used to speaking in public, he was shocked to hear his voice when he spoke from the pulpit for the first time, because “I had never before heard my voice echo back to me”. He remembered the advice of his professor in Pastoral Theology: “If you get stuck, pull all the stops! Take a quick look at your notes and continue!” Wendelin did not need it. Though the pulpit was new to him, he decided to speak freely from the beginning. But he carefully drafted every sermon. Unfortunately, he destroyed his notes as he did most other private papers.

Wendelin’s father considered it an honour to see his son off by “taking a good load of furniture, bed linen and clothes” to Haselstauden, while the young priest, in the company of two clerics from the neighbourhood, followed by coach. Haselstauden, however, wrapped itself in silence. Pfanner was not welcomed by the municipal administrator nor was a single villager on hand to help offload his “dowry”. Strange people, his father thought, shook his head and returned home on the spot.

The rectory seemed to have neither a kitchen nor a cook. The young priest did not see anyone until the following morning when, entering the church to say Mass, a grumbling old sacristan showed him round. But when he stood at the altar he was surprised that “the center aisle was filled with people. It was clear to me that they had not come so much to welcome me as to see who ‘the new one’ was.” How guarded, sceptical and suspicious these Haselstaudeners were! He wondered if he would ever be able to break down the wall behind which they were hiding. He did when typhoid broke out the following spring. It was a onetime opportunity to get to know them, and he seized it straight.

Wendelin Pfanner shortly after his Ordination to the Priesthood

Abbot Francis:

“I visited every affected family. People needed me because hardly anyone dared to go near them for fear of infection. They even told me how much they appreciated the visits of ‘the young gentleman’, as they called me. Their attitude towards me changed overnight. The church began to fill up, not now from curiosity but from a genuine desire to hear what I had to say.”

Biding his time and arming himself with much patience, young Fr. Pfanner won most of his parishioners back to the Church. He listened to them and learned to speak in a way they could understand. He instructed their children in the Faith, heard Confession and sought out the lapsed and critical. Occasionally, he read Leviticus to people who did not keep the Sunday holy, as for example, the innkeeper who when it was time for Sunday Mass sent his hired hands to work in the farm. He also persuaded two wealthy factory owners, both native Haselstaudeners, to donate stain glass windows for the parish church, Our Lady of the Visitation, which he wished to embellish. Their generosity bordered on a miracle. When twenty years later, as abbot of Mariannhill, he visited them, one remarked: “It would have been better if you had not become a Trappist. Why did you have to go so far away, first to these godforsaken Bosnians and then to the Hottentots in Africa? Haven’t we got Hottentots enough to convert?!” Nevertheless, he gave him a generous donation for the “black Hottentots”.

As for the “pagans of Haselstauden”, the young priest did all he could to strengthen their faith. For example, he invited excellent Redemptorist or Jesuit speakers to hold a parish mission. They did so with much success, the said factory owners allowing their employees to attend even on working days.

Whey Cures in Switzerland. Farewell to Haselstauden

Wendelin’s health deteriorated during his very first year in the ministry. This, though, was not the result of lack of care, because his sister Kreszentia, who had decided to stay single, was his housekeeper and looked very well after him. He developed a lung condition (TB?) and his doctor suggested that he drink whey at Gais in Canton Appenzell, Switzerland. The weeks he spent there were restful and relaxing but they did not bring about the desired cure. Abbot Francis: “The peaceful atmosphere and carefree time, the healthy air and diet probably helped me more than the whey.” As long as he had to preach, teach and hear Confessions there was little hope of recovery, leave alone a long life. So he decided to buy a burial site for himself and his sister just beside the Haselstauden church. For the rest, he served without sparing himself. In Anton Jochum, pastor of a neighbouring parish, he had a best friend and adviser. “When I was not sure about something, I consulted him and he always put me at ease, so that I saw my way again. I also gained a lot by listening to him explaining the Catechism and preaching. An excellent man, he had only one fault: he snuffed and that even during Mass! I drew his attention to it ever so cautiously but he just shrugged it off: “Alright, alright. Young men have fine manners! But you are right. Trouble is that I am too old to change.”

Though Fr. Pfanner was burdened with parochial duties he continued to mingle with people, his own family included. They could count on him. His father passed away in September 1856, but his stepmother lived for another twenty-four years. Her oldest son, Franz Xavier, married into a family at Gruenenbach in Bavaria, where as a young man he fell to his death from the threshing floor. When Wendelin’s twin brother Johann married outside the village, the Langen-Hub farmstead switched hands. Johann raised ten children. Nine were baptized by their priest uncle; the oldest was kicked by a horse and died in 1905.

In 1859, the vicar general of Vorarlberg sent Fr. Pfanner to Agram (Zagreb) in Croatia as confessor to a community of Mercy Sisters. Because these had originally come from Southern Tyrol, they were German speaking and needed a German-speaking priest. So Fr. Pfanner left Austria but not before inviting his unsuspecting parishioners to an auction sale of the cacti he had raised. They were a rare spectacle and for him a hobby the doctor had recommended as a pastime for the long winter months. He had a green thumb and in no time transformed the rectory into a sea of blossoms.

Abbot Francis:

“How little did I dream then that one day I would live in a land where the most luxurious cacti grow wild like the nettles in Europe! I had collected some thirty species and by grafting them one on another top of another I produced spectacular forms: balls, snakes, rocks and exotic shapes. I also had the exquisite Eriesy. From books I read I knew that it produced an enchantingly beautiful blossom. So when I found a bud on my specimen I was beside myself with excitement. Why, I even postponed a trip to Munich just to see it open!”

Fr. Pfanner traveled to Agram by train, via Landshut, Linz (where he visited his former professor Franz Joseph Rudigier, now bishop) and Vienna.

Confessor to Nuns and Convicts

We may wonder why he was given an appointment for which we feel he was not cut out. The explanation may be found in Brixen. There, his vicar general had consulted the seminary staff and been told by the rector of the Redemptorists, who knew Fr. Pfanner from parish missions, that he was not only a fine pastor but also an excellent confessor. Or was there another reason?

Abbot Francis:

“It was known to everyone in Brixen that I was a tough fellow and that sometimes people, including nuns, needed a firm hand. Whichever, I ended up in Agram …. As was my habit I said Mass quickly. Therefore the young priests at the convent and perhaps also the one or other Sister did not pin too much hope on the new confessor. They said: ‘Short suit (cassock worn in Vorarlberg), short Mass’ … There were three other priests in residence: the superior, four years my senior and like myself from the Brixen Diocese, a young preacher and a still younger teacher, both Croatians and lecturers at the seminary. We took meals together but otherwise had each our separate apartment. The Sisters cared for me in every regard and paid me a handsome salary besides.”

Fr. Pfanner’s main responsibility in Agram was to hear the Confessions of the Sisters, preach a German homily every Sunday and teach Religion at the convent school. When one day the chimney caught fire on top of the priests’ house, it was the Vorarlberger, practical and fearless as ever, who climbed the roof and from a window in the attic directed the water supply to the top. It was his day! The Sisters admired him for his courage and skill and changed their attitude towards him.

In the Croatia of the early eighteen-sixties (1860/1861), as in many other European countries, the desire for national identity and unity was not to be suppressed any longer. The urban elite, consisting mainly of professors and students, shouted the much-heard slogans clamouring for “national consciousness” and civil liberties.

Abbot Francis:

“Vienna had tried far too long to Germanize the Croatians; now they turned the tables on the Empire. Their aversion to ‘Swabians’. (Germans) was so great that in their coffee houses they used the then fashionable German top hats as spittoon bowls.”

Although Fr. Pfanner and his Austrian fellow priest were allowed to stay and the latter kept a very low profile, Wendelin continued undaunted to hear Confession at the various institutes run by the Sisters and four times a year also at the high security prison of Lepoclava.

A Pilgrim-Tourist in Rome

Early in 1862, Confessor Pfanner read the announcement that the first forty-two Japanese Martyrs were to be beatified in Rome. It was a rare and exciting opportunity to see the Eternal City! In no time he was ready to go. He spent eighteen days in Italy. His first visits were to the ancient shrines. By sheer luck he also caught a close glimpse of Pope Pius IX, an episode he later recounted together with other adventures.

Abbot Francis:

“I left the house before dawn and did not return before ten in the evening. Determined to waste no time, I took something to eat at a roadside coffee house or trattoria, whichever was more convenient and not at the pensione. In this way I was able to explore all four quarters of the City according to a plan I drew up. But very soon I got around without it. Despite the Roman heat I tramped to the Seven Major Churches in and outside the City in one day!”

Once when he came near the entrance of the Sistine Chapel he chanced upon a group of ladies and gentlemen assembled there, all elegantly dressed in black. Inquiring what was going on, he was told that the pope was celebrating an anniversary Mass for his predecessor, Gregory XVI. Entry was strictly by ticket. Too bad! But there must be a way of getting around the ticket, even though he only wore a short soutane instead of the long cassock customary in Rome. He tried:

“I walked over to one of the two young Swiss Guards, smiled and said: ‘Nu, an Landsma weret ihr do inne lo?‘. (You surely allow a countryman to enter, don’t you?) Though trained to keep their face straight, these guardians of the law in their stiff halberds could not supress a smile. Before I knew, one lifted the curtain just enough to call to the captain inside: ‘A Landsma!’(a countryman). The captain understood at once, batted his eyelashes and motioned to me to come forward. I was not asked twice but made my way into the Chapel. Once inside, I walked with all the self-assurance I could muster among the elite of the Roman clergy and aristocracy, all in top array, standing there at attention. And because the clergy was stationed in front of the laity, I ended up right behind the cardinals. These knelt in a semicircle around the altar, the pope himself kneeling by himself on a raised platform. Not for a mint of money would I have changed places with anyone! I was privileged not only to see the Sistina, but also to listen to Gregorian chant, the authentic Roman chant! … You see, even a blind hen sometimes finds a grain of corn! I thanked God that my mother did not speak standard German with us, or else I would not have got in there.”

Always a pastor and a witty one at that, Abbot Francis adds a practical application:

“So also will it be at ‘heaven’s door’ when the end of the world is upon us. Whoever does not have the right ticket will not get in, unless perchance he speaks a known language or happens to be a countryman of Saint Peter!”

Still in Rome, a chance cropped up to see a little more of Italy. A group of tourists were about to set off on horseback to Mount Vesuvius. Anyone was welcome to join. As usual, Wendelin’s mind was made up immediately. Leaving Naples, it was he who led the group up the mountain. What was Vesuvius compared with Vorarlberg’s summits? He was the first one on top and, reckless as usual, stood so dangerously close to the crater’s mouth, that the others shouted to him to be careful. The edge was crumbly and the crater had spat fire only six months earlier!

Back in Agram, Fr. Pfanner reviewed his Italian experience. He had spent much time at the tombs of the Apostles, pondering what he should do with the rest of his life. His health was not good and the atmosphere in Croatia, hostile. Perhaps he should enter a monastery and spend the few years remaining to him in prayer and penance to prepare for death? The thought stuck. Soon it was only a question of which Order to choose, the Franciscans or Jesuits.

While he was still undecided, two men in brown garb came to the convent door. They were Belgian Trappists begging for alms for their monastery. This was towards the end of 1862. Fr. Pfanner’s curiosity was roused by the strange apparel of the monks and until late that evening he questioned them about their Order and lifestyle. “Trappist” – the very name mesmerized him. Then and there he decided: “I will rather die from penance [as a Trappist] than from studies [as a Jesuit]!” That very night he wrote two letters, one to his bishop to dispense him from the diocesan ministry; the other, to Mariawald in Prussia, the only Germanspeaking Trappist monastery, to apply for admission. The Prior replied by return post: “Come!” Our would-be candidate was happy but wondered if he had included enough information. So he wrote again, this time also mentioning his two hernias and his voice which might not be an asset to the choir. Abbot Francis: “The second reply took a little longer and was perhaps also a little more reluctant than the first.”

III. Pilgrimage to the Holy Land

Sightseeing in Egypt. Farewell Letters to Friends

Fr. Pfanner was still waiting for a reply from Brixen. The bishop was a former seminary professor of his and took his time, since he knew him well.

Meanwhile, the Severin Association of Vienna was looking for a priest to lead a group of pilgrims on a tour of the Holy Land. The advertisement was a heaven-sent for Fr. Pfanner. He immediately applied and being just as promptly accepted, began to make preparations. First he ordered a proper saddle from the workshops of Lepoclava, because Arab saddles, as he was told by travelers to the Near East, were sheer torture for Europeans. To the Sisters, however, he did not breathe a word about his plan to become a Trappist. They thought that he wanted to improve his knowledge of Scripture by going to the land of Scripture. But to his bishop to whom he wrote a second time he did confide that he wished to see the Lord’s homeland before burying himself in a Trappist monastery.

The group he was to guide met at Trieste. There he was given his official appointment and all the faculties he needed as president. Apparently, the organizers had been told that he spoke Italian and a little Arabic. Above all, they seemed to have known that he was not a coward. The group was mixed and manageable. It included three priests. One of them, a teacher of Religion at a gymnasium in Bohemia, he appointed treasurer. Then there was a rural pastor in his seventies, also from Bohemia, and an assistant priest from the Diocese of Regensburg. A young probationary judge from Wuerzburg was made secretary. But a Hungarian pensioner proved such a pain in the neck that “we would have been better off without him”. No one in the group had ever been outside his home or traveled. They boarded a steamer destined for the southeastern ports. As soon as it put to sea president Pfanner, like most other passengers, became seasick. “Only my secretary was spared the scourge!” They traveled via Corfu to Rhodes and Cyprus and from there to Lebanon.

Wendelin Pfanner (Confessor to Sisters at Agram, Croatia) as pilgrim’s guide to the Holy Land

In Beirut, he bought a riding crop to keep away “the crooks and rogues” who lay in wait at every city gate to pillage and plunder unsuspecting pilgrims, not simply demanding but extorting bakshish. He did not hesitate to lash out at them, commenting that “nobody would have suspected this whip swinging commander to be a kid-glove confessor to Sisters.” The group considered itself fortunate to have him.

Haifa was the first port of call in the Holy Land where they were allowed to go ashore. They climbed Mount Carmel and afterwards sailed to Jaffa (Joppa, Tel Aviv-Jafo) and there disembarked for good. It was a one of a kind experience: Arab porters stood ready to carry them like sheaves through the churning sea, after which they set them down on the beach. Once ashore, they were on “holy ground”. They knelt to kiss it.

The seasickness was gone as if it had never existed. So the tour of the Holy Land could begin.

After his return to Agram, Fr. Pfanner described his experiences in a letter to his mother and siblings, dated 4 June 1863:

“As president of the pilgrimage, I wasted precious time on official errands and visits besides acting as interpreter for my group. During Holy Week, I celebrated Mass in the very place where Jesus was nailed to the cross. I was so moved that for a moment I could not continue with the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar. On Holy Thursday, I had the honour of being one of twelve pilgrims who had their feet washed by the Patriarch of Jerusalem. Yes, this prelate of supreme rank washed, dried and kissed my feet! He also gave everyone a small cross, carved from the wood of the olive trees which still grow in the Garden of Gethsemane where Jesus suffered his agony before he died. On Good Friday, we visited the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem. We kissed each Station but otherwise felt most unworthy to be without a cross in a place where Jesus carried such a heavy cross! The following night, in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, we listened to the seven sermons traditionally preached there in seven languages: Italian, New Greek, Polish, French, German, Arabic and Spanish. At five o’clock on Easter morning I was allowed to say Mass in another special place: the very tomb in which Jesus was buried … It was a rare opportunity which not even a high ranking Franciscan enjoys who perhaps spends his entire life in Jerusalem, because priority is always given to visiting personalities.”

When the Easter celebrations were over the group rode to Bethany where Lazarus had been buried and raised to life. Then they continued to the place in the desert where Jesus had fasted for forty days. From there they proceeded to Jericho and the Jordan River. They pitched their tent on the bank and went into the water to fill their bottles. Afterwards they followed the Jordan to the Dead Sea and climbed the hill country to see the Church of the Manger and the Shepherds’ fields at Bethlehem. At Hebron, which they visited next, they remembered Abraham, and at St. John-in-the-Mountain, the Holy Baptist.

So far their journey had been without incident, but on this last leg the president’s horse stumbled. But for the fraction of an inch he would have plunged into a ravine. In another instance the horse did throw him in full gallop, but both times he and the horse got away with a bruise and a shock.

After a brief sojourn in Jerusalem, the president led his group to Sichem to see Jacob’s Well, then up Mount Gerizim and on to Nazareth. Later they climbed Mount Tabor from where they descended to the Sea of Galilee, in order to continue along a road leading to the Hill of the Beatitudes and the plain where Jesus multiplied the loaves. Via Cana in Galilee, renowned for the Lord’s first miracle, they returned to the sea. There they made a cash check.

Abbot Francis:

“Before we left Palestine, we distributed the remaining money. Everyone got back 93 guilders. Latest now they realized that their president had managed the tour to their benefit. They had saved money though they saw more than most other pilgrims … Now everyone was free to choose his own way home, make his own plans and manage his own funds.”

Fr. Pfanner decided to return via Egypt. Would anyone like to come along? Most did and promptly re-elected him leader.

In the Land of the Pharaohs

Embarking at Haifa, they were told that the crossing to Alexandria would take twenty-eight hours. They braced themselves. But then the sea changed; it became so rough and the going so slow that it took them more than twice the length of time: sixty-eight hours! A nightmare for the leader!

Abbot Francis:

“Sailing was torture. I was so seasick that I vowed to myself a hundred times over never again to set foot on a boat. I must laugh as I write this. What good are man’s plans if God makes his own? The proverb that man proposes and God disposes couldn’t be more accurate.”

Yes, God has his own plans. As in Pfanner’s case, so he writes straight also with the crooked lines of our own lives. In Alexandria, Fr. Pfanner stood for the first time on African soil. Little did he dream that this was his introduction to a continent where, further in the south, he would labour for twenty-seven years to establish God’s Kingdom!

Cairo was memorable on account of the Pyramids and the Sphinx but also for an unfortunate incident. Shifty porters cut his saddle bag and stole his coat with his journal. Disappointed and angry, he comforted himself with the thought that “as a Trappist I will have no use for either, my coat or my journal”. Leaving the Pyramids, he and his group traveled far “to the place where, according to tradition, Mary and Joseph had stayed in hiding with their beloved Child”. They also visited the “Mary Tree” and “Mary Fountain” which according to legend had offered the Holy Family shelter and water.

Suez on the Red Sea – the canal was just then being built – was their next destination:

“Our short stay at the little town of Suez turned into a distressing experience for me. I caught dysentery, wide spread in those parts, which confined me to my room for several days. Relief finally came in the form of a remedy the hotelkeeper offered: rice cooked in unsalted water. Later, in Bosnia, I prescribed it to great effect for my sick Brothers, and when I was in London I was able to cure a whole family with it.”

The group disbanded at Suez and everyone went home by his own way. Fr. Pfanner chose to travel via Constantinople “on the same ticket and for the same fare”. He was much impressed with the Golden Horn and a cruise on the Black Sea. From Kuscendje he journeyed by train to the Danube and by a Hungarian steamer up that great water way to Belgrade and Semlin. There he transferred to a Sava-boat and later once more to a train which eventually took him to Agram.

“When my coach drove through the convent gate and I got off, no one welcomed me. Sister Portress did not recognize me on account of my pilgrim’s beard which, as a matter of fact, had not felt a razor for fully three months! I wore it for three more days and during that time paid my respects to the cardinal archbishop.

The glory of the world and its pomp held no more attraction for me. I was only waiting for the letter that would allow me to leave the world. There were all kinds of letters waiting for me on my return but none from my bishop. So I wrote again. This time I mentioned my visit to the Orient and the Holy Land and that everything was but vanity. The only wisdom, I concluded, was to serve God in order to see him when life was over.”

This time the bishop answered by return post. He wrote that he envied Pfanner his “holy solitude” and would love to hide himself away as well, if only he were free.

Goodbye to the World

Before leaving the world for good, Fr. Pfanner took leave of close relatives and friends. In a letter to his classmate Berchtold, pastor of Hittisau in Vorarlberg, he recalled their ordination thirteen years earlier and touched on his recent experiences. Returned from a great journey that took him: “from the cedars of Lebanon to the Red Sea with its pearl oysters”, he had no words to describe what he had seen and felt. He could only hint, for “at such times the heart is drowned in the joys of a world it has never known”!