Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

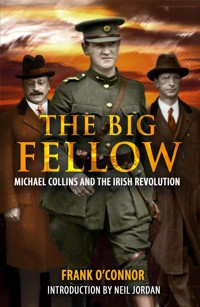

Re-issued with an introduction by Neil Jordan, 'The Big Fellow' is the 1937 biography of the famed Irish leader Michael Collins by acclaimed author Frank O'Connor. It is an uncompromising but humane study of Collins, whose stature and genius O'Connor recognised. A masterly, evocative portrait of one of Ireland's most charismatic figures, 'The Big Fellow' covers the period of Collins' life from the Easter Rising in 1916 to his death in 1922 during the Irish Civil War. The author, having served with the Anti-Treaty IRA during the Irish Civil War, wrote 'The Big Fellow' as a form of reparation over the guilt he felt with regards to taking up arms against his fellow Irishmen and Collins' untimely death. Liam Neeson has said that he found the book of great assistance when preparing for the role of Collins in the 1996 film directed by Neil Jordan.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 375

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Frank O’Connor, 1937

Revised edition first published 1965

This edition first published 2018

© Introduction: Neil Jordan, 2018

ISBN: 978 1 78117 558 3

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 559 0

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 560 6

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Acknowledgements

I am painfully conscious of the inadequacy of an acknowledgement such as this, of the hospitality, the kindness, and often the quite considerable assistance I have received from Collins’ friends, many of whom are now dead. Particularly do I feel its inadequacy when it concerns Colonel Joseph O’Reilly and Dr Richard Hayes. I am much indebted also to Messrs Frank Aiken, Robert Barton, Piaras Béaslaí, Ernest Blythe, Colonel E. Broy, Seán Collins, W. T. Cosgrave, Craig Gardner and Co., Liam Devlin, George Gavan Duffy, Eamon Fleming, Thomas Gay, Christopher Harte, Liam Lanigan, Stephen Lanigan, Diarmuid Lynch, Fionán Lynch, Miss Alice Lyons, Patrick McCrea, George MacGrath, Mrs Helen MacGovern, Seán MacEoin, Richard Mulcahy, Fintan Murphy, Mrs Fintan Murphy, David Neligan, Michael Noyk, Mrs Batt O’Connor, Florence O’Donoghue, P. S. O’Hegarty, Patrick O’Keeffe, Ernest O’Malley, Colm O’Murchu, Gearóid O’Sullivan, Frank Saurin, Frank Thornton and Liam Tobin.

F. O’C.

Introduction

When I was asked by the film producer David Puttnam, more years ago now than I want to count, if I wanted to write a script about Michael Collins, I immediately said yes. But I had to keep to myself how little I knew about the man.

I remembered three biographies of Collins on my father’s bookshelves, one by Piaras Béaslaí with a faded hardcover, and two paperbacks, one by Rex Taylor and the other by Frank O’Connor, with militaristic covers of a man in a green uniform gazing off towards some imaginary future. The background to one was a greener shamrock, as far as I remember, and to the other, a green, orange and white tricolour. I had little interest in uniforms, green or otherwise, as a kid and even less as an argumentative adolescent. So Michael Collins belonged not so much to a distant past as to a period that didn’t seem to have any real existence. There was a boy in my class – in St Paul’s, Raheny – called Oscar Traynor, and there was a road close by that ran through to Coolock, called Oscar Traynor Road. We never connected the boy to the road, though it shared his name and was called after his grandfather, who had fought in the War of Independence. Around the corner was Collins Avenue, which led from Killester to Glasnevin, where Collins and indeed Éamon de Valera were both buried. But Collins Avenue to us was just a road that led to the Beachcomber pub.

De Valera we knew something about, of course, because he had appeared with a hurley stick outside Áras an Uachtaráin with President John F. Kennedy. But why his name gave rise to whispered arguments amongst uncles and aunts was never really explained. This was the mid-1960s and the really important antipathies were between mods and rockers and The Beatles and The Rolling Stones.

So I went back to my father’s house and borrowed all three biographies. Piaras Béaslaí’s I found was a piece of pure hagiography. Historically accurate, I am sure, but a portrait of such an immaculate hero-figure, half Cúchulainn and half Mussolini, that my first instinct was to call up Mr Puttnam and say no. Rex Taylor’s was a fast-paced read, but the book that really brought Collins alive to me was Frank O’Connor’s The Big Fellow. It had the immediacy of a life really lived, and towards the latter half, a sense of genuine tragedy that seemed to be personally felt, still raw and painful. Frank O’Connor had of course fought on the opposite side to Collins in the Civil War and experienced all of the confusion of divided loyalties and the bitter waste of argument over the Treaty Collins brought back from London. He had already written one of the great, perhaps the greatest, stories of the absurdities of conflict in Guests of the Nation. (I was to plunder from it wholesale, many years later, in the first third of The Crying Game.) Which must be why his portrait of a man of lethal action, with ‘no power of abstract thought’, trying to keep his own and his movement’s tarnished moral universe intact, is so unforgettable.

Neil Jordan

Foreword

This book has been a labour of love. To some extent it has been an act of reparation. Since the fever of the Civil War died down I have found myself becoming more and more attracted by Collins as a character. For a while I toyed with the idea of a novel. I continued to hear anecdotes of him, and again and again I was struck by their extraordinary consistency. I can remember well the occasion when anecdotes became something more. My friend and colleague, Mr Gay, was speaking to me of Collins, and so finely did he recreate his dead friend that for the first time I seemed to see Collins as a living man. Half a dozen times since, I have caught the same thing from others of his friends, and each time it was as though a ghost had walked in. Those friends of his will, I feel sure, forgive me for blurring that sense of the living man. It is something which is part of their experience and scarcely to be communicated; what catches fire in speech rings cold in print: exaggeration, false emphasis creep in; yet I should think it a greater loss if that image of the living man, however broken, were lost, than if all the documentation concerning him were to disappear. How often we would sacrifice a hundred studio portraits for one snapshot!

And here a word of warning. Anecdote preserves the living man, but it exaggerates him. When the documents are published it will be seen that Collins was a much greater figure than was suspected by any but a few. But the greater part of Collins’ life is in those papers. For a few moments each day he was the schoolboy, the good companion, the great friend, but for the rest of the time he was the worker, and to deal with him without dealing exhaustively with that work scants the respect due to his industry, patience, good humour and splendid intellect. To give a complete picture of the man one would need to weight down the brilliant sensitive temperament as he himself weighted it, with a mass of arduous and scrupulous labour. But documents – bless them! – have a habit of surviving, and how much of the living man has perished even now I do not care to think.

I have written not for Collins’ contemporaries but for a generation which does not know him except as a name. His friends are properly jealous of his reputation, but sometimes in safeguarding reputations we lose something a thousand times more valuable – the sense of a common humanity. A new generation has grown up which is utterly indifferent to the great story that began in Easter 1916. It is even bored by it. We may rage, but can we really expect young people to be interested in the utterly unhuman shadows we have made of its heroes? They don’t drink, they don’t swear, they don’t squabble; they never make fantastic blunders; one is never less wise, urbane and spiritual than the others; they address one another with the exquisite politeness of Chinese mandarins. We, alas, go on drinking, swearing, fighting and making mistakes, and so have no time to spare for this cloudy pantheon of perfect and boring immortals.

I have taken no pains whatever to conceal the fact that Collins was a human being, that he took a drink, swore and lost his temper. It is not as though there was anything to conceal. The worst one can say of him is so trifling that only a mean spirit would distort it to decry him. Without that worst the best rings false, and with Collins the best is always well worth telling.

At any rate it would be a poor compliment to so great a realist. It is as a realist Collins will be remembered, and as a realist he should be an inspiration to the new Ireland. From the Civil War and the despair that followed it sprang a new honesty in Irish life and thought. The old sentimentalism against which Collins almost unconsciously strove has suffered.

I have to acknowledge my deep indebtedness to those authors who have permitted me to make use of their work. I name especially Mr Piaras Béaslaí, whose monumental life of Collins should be read as a corrective to mine; Mr Pakenham, now the Earl of Longford, whose brilliant analysis of the Treaty negotiations, Peace by Ordeal, I have shamelessly pillaged; Dr P. McCartan, who allowed me to make use of his With De Valera in America; and Miss Dorothy Macardle, who very generously lent me the proofs of her book The Irish Republic, without which I should have found it almost impossible to deal with anything like adequacy with the last period of Collins’ life. There are several other books which have been of service to me: Mr Batt O’Connor’s moving autobiography With Michael Collins; Mr Charles Dalton’s With the Dublin Brigade (a beautiful little book which has never received proper praise); Mr Desmond Ryan’s Remembering Sion, which contains unforgettable portraits of Collins and other leaders; Mr Hayden Talbot’s Michael Collins’ Own Story, which contains a great deal of valuable biographical material; Mr James Stephens’ monograph Arthur Griffith; Mr Darrell Figgis’ Recollections of the Irish War; Major-General Sir C. E. Callwell’s Field-Marshal Sir Henry Wilson; Mr P. S. O’Hegarty’s Victory of Sinn Féin; Mr Winston Churchill’s The World Crisis. In this new edition I have made use of Ernest O’Malley’s On Another Man’s Wound and Rex Taylor’s Michael Collins, but I have preferred not to re-write.

F. O’C.

Publisher’s Note, 2018: A small number of footnotes have been added to this new edition to explain people, events and terms the reader may not be familiar with. Page numbers and publishing details have also been added to the references from the original revised edition, where possible.

1

Lilliput in London

One cold bright morning in the spring of the year of fate, 1916, a young man in a peaked cap and grey suit stood on the deck of a boat returning to Ireland. He was in his middle twenties, tall and splendidly built, with a broad, good-tempered face, brown hair and grey eyes. His eyes were deep-set and wide apart, his nose was long and fine, his mouth well arched, firm, curling easily to scorn or humour. One interested in the study of behaviour would have noted instantly the extreme mobility of feature which indicated unusual nervous energy; the slight swagger and remarkable grace which indicated an equal physical energy; the prominent jowl which underlined the curve of the mouth; the smile which gave place so suddenly to a frown; and that appearance of having just stepped out of a cold bath which distinguished him from his grimy fellow travellers; the uninterested would have passed him as a handsome but otherwise ordinary young Irishman, shopman or clerk, returning from England on holiday.

It was ten years since this young man, Michael Collins, had left his native place in West Cork. A country boy of fifteen, precocious and sturdy, he had taken the train from the little Irish town where for a year he had been put through the mysteries of competitive examination. With his new travelling bag and new suit, which included his first long pants, he had crossed the sea and passed his first night in exile amid the roar of London.

The boat crept closer to the North Wall. He saw the distant mountains heaped above the city, its many spires, its dingy quays. Everywhere the bells were calling to Mass. It might have been the same Dublin of years before, but beneath it was a different Dublin and a different Ireland. Then it had been butter merchants, cattlemen, labourers who chatted with the manly youth with the broad West Cork accent. Now it was soldiers returning on leave from the war, some lying along the benches, their heads thrown to one side, their rifles resting beside them, while others, too excited to rest, paced up and down the deck, glad another crossing was over without sight of the conning tower of a submarine. He chummed up with two of them. Some time soon he felt that, instead of chatting with them, he would be fighting them.

That was the greatest change. Then there had been no talk of fight. Mr Redmond, the leader of the Irish race at home and abroad, hook-nosed, spineless and suave – a perfect Irish gentleman – was in Westminster and all was well with the country. An election was being held in Galway, and there were brass bands and blackthorns, just as in the good old days. There was money to be made, land to be claimed, position to be secured; all Irish nationalism exacted of its servants was an occasional emotional reference to Emmet on the gallows, Tone with his throat cut. Parnell, whose name the lad of fifteen, following his father, had held dear, was dead, and the intellect of Ireland had been driven into the wilderness. The few who could think were asking what was wrong with the country and giving different answers. Some said it had no literature (‘Literature, my bloody eye!’ chorused Lilliput indignantly, busy with increasing its bank balance and saving its soul in the old frenzied Lilliputian way); some that it had lost its native tongue; some that Westminster was corrupting its representatives and that they would be better at home; some that the workers were being exploited by Catholic and Protestant, Englishman and true Gael alike; some that the whole organisation of society was wrong and that it was vain to increase wealth while middlemen seized it all. Against each of these doctrines Lilliput set up a howl of execration, and the intellectuals of one movement were often the Lilliputians of another. So we find the Gaelic Leaguers ranged against the literary men, and the abstentionists against the workers.

That movement of the intelligence, which Lilliput so deeply resented, had taken place because at the end of the preceding century the great Lilliputian illusion had broken down, the belief that one man could restore its freedom to a bookless, backward, superstitious race which had scarcely emerged from the twilight of mythology. It had broken down because the priests had torn Parnell from his eminence and Lilliput had assented. Sick at heart, the sensitive and intelligent asked what it meant. None said ‘Lilliput’, none declared that Ireland was suffering for its sins, or that Lilliput must cast out the slave in its own soul. That is not how masses change. And so arose Yeats and Hyde, Griffith, Larkin and Plunkett.

In turn each of these waves of revolt had spent itself. Synge was dead, Larkin beaten, Griffith a name. The war had brought Lilliput back in strength. There was nothing Lilliput liked better than a good vague cause at the world’s end – about the Austrian succession, the temporal power or the neutrality of Belgium. Given such a cause, involving no searching of the heart, no tragedy, it can almost believe itself human. In proportion to its population Ireland had contributed more to French battlefields than England itself. Lilliput did not mind if Ireland was still unfree. All in good time. The great jellyfish of Westminster, the invertebrate leader with the hooked nose and cold, mindless face, let slip the one great chance of winning freedom. Without firing a shot or sending a man to the gallows he might have had it, but refrained – from delicacy of feeling. Lilliput is nothing if not delicate-minded. And now, let the war end without war in Ireland, and all that ferment of the intelligence would have gone for nothing. So at least the intellectuals thought, though it is doubtful if a historical process once begun ever fails for lack of occasion.

Michael Collins was coming back to take part in a revolution which the intellectuals felt was their last kick. They were gathering in from the wilderness to which the Parnellite disillusionment had driven them: labourers, clerks, teachers, doctors, poets, with their antiquated rifles, their amateurish notions of warfare, their absurd, attractive scruples of conscience.

It must have been thrill enough for the soul of the young man when the ship came to rest and the gangways went down that faraway spring morning. The ten years of exile were over. Sweet, sleepy, dreary, the Dublin quays which would soon echo with the crash of English shells. Even a premonition of what was in store for him could scarcely have stirred him more or the shadow of his own coming greatness; even the feeling that, his work done, the Ireland he loved set free, he himself would personify a mass possession greater even than that Parnell had stood for, and that from his body, struck down in its glory, the intellect of the nation would pass again into the wilderness.

London of pre-war days was a curious training ground for a man who was about to lead a revolution. The Irish in London – except those who stray, who wish to forget their nationality as quickly as possible – stick together, so that, in one sense, London is only Lilliput writ large. One class, one faith, one attitude; the concerts where preposterously garbed females sing sentimental songs to the accompaniment of the harp, boys and girls dance ‘The Walls of Limerick’ and ‘The Waves of Tory’ and play a variety of hurling.

But the young men of Collins’ day, however their instincts might urge them to resurrect Lilliput in London, did not have to do so. If they did not wish to go to Mass, there was no opinion that could make them; if they wanted to read what in the homeland would be called ‘bad books’, there was nobody to stop them. Collins was lucky, not only in being bundled into a big city where he did not need to grow old too soon, but in having a sister who encouraged his studiousness.

To the day of his death he remained an extraordinarily bookish man. History, philosophy, economics, poetry; he read them all and was so quick-witted that he needed no tutor. He went to the theatre week by week, admired Shaw and Barrie, Wilde, Yeats, Colum, Synge; knew by heart vast tracts of ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol’, ‘The Widow in Bye Street’, Yeats’ poems, and The Playboy.[1] One cannot imagine him doing anything halfheartedly.

Most of the younger Irish, relieved of the necessity for orthodoxy, favoured a mild agnosticism and ‘advanced’ ideas. Collins, who did nothing in moderation, went further: ‘If there is a God, I defy him,’ he declared on one occasion. With great fire and persuasiveness he discussed such ‘advanced’ ideas as the evils of prostitution (which he was shrewd enough to know only at second-hand through the works of Tolstoy and Shaw). Already he was being looked upon as a bit of a character, a playboy, and when in that grand West Cork accent of his he rolled out the Playboy’s superb phrases about his father’s ‘wide and windy acres of rich Munster land’, or of being ‘abroad in Erris when Good Friday’s by, making kisses with our wetted mouths’, of the Lord God envying him and being ‘lonesome in his golden chair’, he was Christy Mahon incarnate, who for the fiftieth time was slaying his horrid da with a great clout that split the old man to the breeches belt.

But the old da refused to die. In fact his life had never been in danger. When members of his hurling club debased themselves by playing rugby, Collins was the hottest advocate of their expulsion. When a poor Irish soldier appeared among the spectators on the hurling field in uniform, Collins drove him off. When Robinson’s Patriots was produced in London, Collins went to hoot it because Robinson dared to suggest that the people of Cork – his Cork – preferred the cinema to a revolutionary meeting.[2] In fact Collins’ studiousness was the mental activity of a highly gifted country lad to whom culture remained a mysterious and all-powerful magic, though not one for everyday use. His reading regularly outdistanced his powers of reflection, and whenever we seek the source of action in him it is always in the world of his childhood that we find it. When excited, he dropped back into the dialect of his West Cork home, as in his dreams he dropped back into the place itself, into memories of its fields, its little whitewashed cottages, Jimmy Santry’s forge and the tales he heard in it. There was rarely a creature so compact of his own childhood. To literature and art the real Michael Collins brings the standards of the country fireside of a winter night, emotion and intimacy, and that boyish enthusiasm which makes magic of old legends and can weep over the sorrowful fate of some obscure blacksmith or farmer. The songs he loved best were old come-all-ye’s of endless length, concerning Granuaile or the Bould Galtee Boy:

Bold and gallant is my name,

My name I will never deny,

For love of my country I’m banished from home,

And they calls me the Bould Galtee Boy.

The student in him found pleasure in Yeats; his turbulent temperament found most satisfaction in songs like this which came out of or went back to the life from which he had sprung; the thing of which he seems to have known nothing and cared less is the great middle-class world of approximations and shadows. His nature safeguarded him from the commonplace. If his pal Joe O’Reilly sang ‘Máire, My Girl’, Collins got up and left the room impatiently. P. S. O’Hegarty quotes one of his later utterances, and one of extraordinary significance. He made it, O’Hegarty says, with a difficulty in finding the appropriate words; which is not to be wondered at, considering that it was his inmost being he was laying bare:

I stand for an Irish civilisation based on the people and embodying and maintaining the things – their habits, ways of thought, customs that make them different – the sort of life I was brought up in … Once, years ago, a crowd of us were going along the Shepherd’s Bush Road when out of a lane came a chap with a donkey – just the sort of donkey and just the sort of cart that they have at home. He came out quite suddenly and abruptly and we all cheered him. Nobody who has not been an exile will understand me, but I stand for that.

There were three qualities which marked Collins all his life long: his humour, his passionate tenderness, his fiery temper – and who shall say it is not an Irish make-up? Strangers usually saw the temper first. He was fond of teasing, was always making a mock of London-born Irish, and on the hurling field his loud voice pealed out in good-humoured gibes of ‘’It it, ’Arry!’ But when he was teased himself he went up in smoke. There is no weakness which men spot sooner or of which they take more advantage. The result was that everyone made a dead set on Collins. It was the same in conversation. When he put his head in everyone turned on him. He was roared down unmercifully, with the inevitable result that he lost his temper. When things developed into a fight he always got the worst of it. The more he tried to assert himself, the more punishment he got. But his tempers never lasted. They blew over in a few minutes, the very worst of them, and then that handsome face of his lit up with the most attractive of smiles; on no occasion does he seem to have borne the least grudge against anyone and what might have been dislike became a good-humoured tolerance. No one could bear malice against a man who bore none, who came up smiling every time and took fresh insults and fresh clips on the jaw with a gorgeous fury which remembered nothing of previous ones.

Collins’ youth, for a novelist, represents the most fascinating part of his life. In this we see the first threshings of his genius in a world which did not recognise it. Something similar occurs in the life of every great man. There is a gruesome period when his daemon compels him to behave like a genius, and the crowd, sensibly refusing to take it on trust, sets upon him. As a boy clerk Collins behaved as though he owned the Post Office. All he demanded of his pals was that they should recognise him as a great leader of men on his own unsupported testimony; they insisted on treating him as no better or wiser or stronger than themselves.

There is always something adorable (afterwards) in the picture of genius throwing itself upon the barricades of reality. That is the real explanation of Collins’ anti-clericalism. He wanted to lead; he was gregarious and bossy; organised concerts, picnics and dances. One can scarcely imagine him except in company. He drank, though never to excess, and swore with a thrilling capacity for improvisation, and always there was that bubbling humour. W. P. O’Ryan tells how he once refereed a ladies’ match and threatened to send off one of the girls for using bad language! He was the sort of charming lad who is always trying to sell you tickets for something or other and is cut to the heart when you refuse to buy.

He knew quite early that there was something on in Ireland, and he wanted to be in it; more than that, he wanted to be prominent in it. When Lanigan took a job in a provincial town, nothing would persuade Collins but that he had gone to Ireland in view of an imminent insurrection and that the job was a blind. So, in time, he went himself to Dublin, and got in touch with Tom Clarke and Seán MacDermott, who, having no need of a butt, recognised the lad’s enthusiasm and energy and gave him work to do in London. Collins was happy at last. A few days before, fresh from Seán and Dublin, he had burst in upon a meeting of the London-Irish, who were discussing sending a deputation to Westminster to protest to Redmond against being conscripted, and warned them to clear back to Ireland as soon as they could. So the little group broke up to meet again in the streets of Dublin.

Now that Collins has become history it is easy for us to see what was most real in him in those London days: the necessity to lead and the love of traditional life. It is the donkey and cart of Shepherd’s Bush Road. That donkey and cart was never far from Collins’ thoughts: it emerges like a motif in the story of his brief life, sentimental here, jesting there, uncouth and over-boisterous in another place. At the end of his days it is repeated, louder and more menacing, until it assumes a tragic personal significance. It strips off the adopted disbelief; it justifies him when he feels most uncertain of himself; it sets him against his dearest friends in the most sordid of wars. He is a man possessed of a boyish loyalty, a vision of whitewashed cottages, of old people sitting by the fire, of horses outside the forge on a summer evening. Like all precocious boys he admired older men. Reverence, he said to Hayden Talbot, was his strongest characteristic.[3] His father was an old man when Collins was born, and the lad worshipped him. One day they were in the field together, the barefooted boy and his father. The father, mounting a fence, pushed loose a heavy stone which rolled towards Collins. He made no attempt to avoid it and watched it until it crushed his instep. He could not believe his father could cause such a thing. ‘Great age,’ he said to the same biographer, ‘held something for me that was awesome. I was much fonder of old people in the darkness than of young people in the daylight.’

In others ideals tend to become abstract. In him the fact of his deep and burning idealism tended to be obscured because it was earthy and tough. Opposed by the superior motives of a Mellows or de Valera, he is at a disadvantage; clumsy, blundering, giving an impression of disingenuousness; for men and women are notoriously nasty, and abstract principles tenuous and pure, and they live and die austerely if they can be said to live or die at all.

2

Up the Republic!

At the top of O’Connell Street stands the red-brown monument to Parnell. Left of it is the Rotunda Hospital, a severe eighteenth-century building with a narrow strip of garden before it. To the right, at the corner of Parnell Street, stood in those days a little tobacco shop which all young Dublin knew.

Inside the counter of the little shop was a little man. He was sixty years of age, spare and spectacled. When you entered he looked at you first over his spectacles and then through them. Sometimes young men came and chattered to him, elbows on the counter; sometimes they retreated into the parlour behind the shop. He favoured young men. They bought Irish cigarettes and went to Irish concerts and dances; they talked Irish, mostly bad. It was all so different to his youth. Then there was no talk of Irish this or that, and though the young men might have heard Irish spoken in their own homes they did not speak it themselves. They were good boys, those of long ago, but these were better. It is a happy old age which can see the world improving.

Yet the world had been hard enough on old Tom Clarke. For sixteen years it had shut him up in English prisons among murderers and thieves. His comrades had gone mad. He, too, might have gone mad but for his indomitable youth. Had he not in the printing shop of the prison, under the eyes of warders and touting prisoners, secretly printed a newspaper, filled with imaginary news – imaginary because he was allowed to know nothing of the world? Had he not, after years, elaborated a means of receiving real news, only to have it snatched from him again? It was a terrible fate, that of Tom Clarke. Even to read of it now, as he described it, with a deep sense of reality so lacking in books by Irish revolutionaries, makes one shudder; but this little old man was able to recreate it all in his mind in the slack hours before sleepy Dublin comes awake, when its streets are like those of a country town, and not only keep his sanity but plan for such another horror in which to end his days.

And the young men would join him. He trusted them, they admired him. They were a queer lot. Several were poets. The young men of Clarke’s day had been poets, too, but they wrote things you could understand about ‘Dear Old Ireland’ and ‘Our Martyred Dead’. Plunkett and Thomas MacDonagh wrote English poems that were as foreign to his straightforward mind as the Irish ones of Pat Pearse.

Pearse was a dreamer if ever there was one. He was a mixture of Byron and Oscar Wilde, blended by the pious Catholic teaching of the Christian Brothers. He ran a school outside Rathfarnham, where the boys were taught to resemble the heroes of old sagas. He wrote mostly in Irish, and that deplorable, and was proud of his ability as an orator. His literary efforts show the same blend of fustian and dandyism; they are mannered, morbid and effeminate. To an English father he probably owed the streak of eccentricity. The Dubliners thought him pretentious and a bore.

Thomas MacDonagh was typically Irish; a too-volatile nature, he talked, talked, talked, wrote, wrote, wrote, and talk and verse had the same learned loquacity. An attractive figure, MacDonagh; an adventurer in letters, like a seventeenth-century Irish gentleman in the French or Spanish army; the outline of a great man but without the intellectual substance. From his fatal facility there emerges but one great poem. His volatile nature permitted him at the end to scoff at mere literature and ask when the poets would settle down to tactics. Dublin, which had sniggered at MacDonagh the poet, did not spare MacDonagh the tactician.

His friend, Joe Plunkett, had travelled at lot. He was even then a dying man; swore by Francis Thompson and G. K. Chesterton, and imitated them with lamentable results. A far greater influence was Seán MacDermott, who remains, when everything has been said, a shadowy, mysterious figure. For the effect he had upon men as mature as Collins, Diarmuid O’Hegarty and O’Sullivan one can show no cause.[4] Apparently he was merely a good-humoured, eager, handsome young cripple with a coaxing tongue, adored by every newsboy in Dublin – as Collins was later to be – his only accomplishment a gift for reciting fiery ballads:

Brian of Banba all alone up from the desert places

Came to stand where the festal throne of the Lord of Thomond’s race is …

or:

I am Brian Boy Magee,

My father was Owen Ban,

I was awakened from happy dreams

By the shouts of my startled clan.

Some simplicity of life or thought had given him the mysterious power of swaying men; he was a Pied Piper who lured them after him, and to this day they cannot tell what tune he played.

There were others, though it is doubtful if Collins knew or cared much for them, like James Connolly, whom Æ looked on as the one intellect of the Rising.[5] He had had it all planned out for twenty years, and all his socialist activities against the greasy tills of the Martin Murphys had not shaken his determination to have it out with the British Empire too.[6] Arthur Griffith’s political writings had had a considerable influence on Collins. He was a stocky, stubborn bourgeois, Connolly’s antithesis – frigid with shyness, opinionated, indomitable, incorruptible and lonely. ‘Griffith staring in hysterical pride’: Yeats’ great line places him for ever. His only passion was for music; he could whistle thousands of tunes. He was immensely strong. James Stephens describes going home with him one night and seeing him attacked by a corner boy. He knocked down the corner boy and went on with what he had been saying. It was characteristic of the man’s utter imperturbability. On one occasion he mistakenly took a brand-new hat and coat from a rack in the restaurant where he lunched. The owner, a young countryman on his honeymoon, came in great trouble to the men who sat at Griffith’s table. As Griffith had never opened his mouth to them, they had no difficulty in persuading the young man that Griffith was a well-known pilferer of coats and hats. ‘God, isn’t it a cruel world?’ the victim said piteously, and then the door opened and Griffith entered. He returned to the rack, took off the coat and hat, put them in their old place, donned his own and disappeared in the same awful silence. Not a smile! Not an apology! A man of iron but utterly without the capacity for leadership, he sought desperately for someone who would implement his ideas.

The young man he was seeking was in Dublin, staying at his friend Belton’s farm with a relative by marriage, Seán Hurley, and others of the refugees from conscription. Belton was hospitable, but it irked Collins to be without a job. Most of the London-Irish group had settled in a camp at Kimmage and he visited them regularly. When he appeared all work stopped and a chorus of voices intoned tauntingly, ‘Who killed Mick Collins?’ Collins flew into one of his usual rages, and it ended in a free fight, after which everyone was again the best of friends.

In late February he got steady work at Craig Gardner’s with his friends Joe and George MacGrath. Even in so short a time he was modifying his opinions. One anecdote has it that, engaged on an audit with a loyalist Protestant firm, he had hot words with one of the clerks. The accountant in charge of the audit was alarmed when he looked out of his office and saw the young firebrand from Cork squaring up to fight. He called him and read him a lecture. As an accountant he should have no politics, he should do his job and avoid political discussions even when provocation was offered. Collins listened obediently and then a smile broke over his face.

‘As a matter of fact,’ he said cheerfully, ‘it wasn’t about politics – only religion!’

Even for Ireland, the rebellion of 1916 is outstanding for muddle, plot and counterplot, command and countermand, and the utter lack of organising ability at the head. Eoin MacNeill’s countermanding order has been blamed for the final fiasco, but the real responsibility is on those who adopted the childish plan of concealing things from him. One wonders what the Rising would have been like if a great organiser like Collins had been in Ireland for a year or two before; as it is, one can only be grateful that he, too, did not go down in the bloody mess with MacDermott and Plunkett.

At noon on Easter Monday they set out for the General Post Office (GPO). Collins had passed the previous night in a city hotel with his chief, Joe Plunkett. The day began badly for him. The London-Irish contingent from Kimmage was lined up outside Liberty Hall, and great indeed was their surprise when among the leaders, in the full uniform of a staff captain, appeared their old friend Mick Collins. The temptation was too great. They began to make fun of him. Collins went white and clenched his fists.

The guard on the GPO was taken by surprise and surrendered, the little group of civilians was seized and bundled out; the Volunteers drove their rifle butts through the windows and barricaded them, and proceeded to provision their headquarters from the hotel across the street where Collins had passed the previous night. A little crowd, which included some mystified metropolitan policemen and a few soldiers on leave from the front, gathered – mocking and gaping. They scattered as a party of outraged Lancers rode down O’Connell Street at a gallop. They were met by a volley from the newly barricaded windows; some horses stumbled and two men crashed onto the cobblestones near the Nelson Pillar. The tricolour appeared on the roof and was greeted by a feeble cheer from the street. An officer – it was Patrick Pearse – appeared and read a proclamation to the re-formed crowd of gapers. The Republic was in being.

The Republic was in being. The citizens of the Republic heard the news with astonishment. The crapulous women leaning out of fourth-storey windows in the spring sunlight yelled questions to the ladies in bonnets and shawls who raced by below. The underworld stumbled down the high staircases of old Georgian mansions, heads began to emerge at street level from basements to which the sun never penetrates. The sitters on the broad stone steps sprang into unwashed activity, surprise and rage mingling in them. Their sons, husbands, brothers, were at the front, fighting the Germans; the separation money flowed like water through the streets and now the dirty pro-Germans were attacking it. Attacking the blessed separation money!

They crowded in on O’Connell Street, thousands of them, a winning sight for idealists. Now and then a Volunteer sentry fired over their heads and they scurried back with adenoidal shrieks, only to return in a few minutes in greater force.

It was a little while before they recognised the advantages of the new dispensation. Then some rough drove his heel through the window of a sweetshop. Jars of sweets were passed out and distributed generously. Holiday came in the air. Meanwhile uniformed dispatch riders rode up and down the street on their motor bicycles, and cars were seized from their astonished owners.

Within, everyone was strung up, expectant. Connolly, with the irascible efficiency of the old Trades Union leader, had bagged an office and busied himself with the secretary and typists. Collins, equally efficient, emptied two tierces of porter down the canteen drain. ‘They said we were drunk in ’98,’ he commented. ‘They won’t be able to say it now.’ Old Clarke, harassed and excited, was blaming everyone for the mistakes which had been made. Poor Clarke had waited so long, he may well be excused. Pearse was enduring a melancholy he could not shake off and which was made worse by the fact that now the great day had come he had nothing in particular to do but ‘speak to the people’, as his phrase was for those periodical moody addresses. Another sad figure was O’Rahilly. The leaders, ignoring his great sacrifices, his quixotic nobility, had distrusted him; they had not informed him of the Rising, so, labelled a poltroon, he came, but communicated with Pearse and the others only through his subordinates. He was a constant reproach to Pearse. ‘What a fine man he is!’ he exclaimed sadly to Desmond Ryan.[7]

The sound of pick and shovel could be heard eating their way through the rear walls towards Moore Street, in accordance with the Connolly theory of street fighting. The men in eager voices discussed the rumours which were about, that the Germans had landed and the country was up. The women were working downstairs in the basement; there was rice for tea. The London-Irish rowed with Desmond Fitzgerald, who refused them rations without a chit; and Collins, all his rancour against them forgotten, took their part.[8] He had begun to take down the names, addresses and rank of the men on his own landing – the most efficient officer in the whole building, someone called him.

They could hear the crowds in the street outside shrieking ever more wildly as shop front after shop front caved in and goods of every description were passed out. Old women raced away on dancing slippers to get their share of something else. MacDermott came looking for pickets to scatter them. Behind their howling the noise of the city had fallen still. Not a tram, not a car, except some Volunteer car from the country.

Scarcely had they changed guard for the night than the first fire broke out, immediately across the road. The looters had simply set the shell alight, and to the macabre scene within, where some men watched over the sandbagged windows and some lay about the floor asleep, was added the grotesqueness of the crimson light that bloomed and faded and hissed against the high empty windows through which the cold spring wind came unhindered. Collins and his friend O’Sullivan spent the night in the corridor outside the office in which MacDermott, Plunkett and Clarke were catching a rest. They ate hard-boiled eggs, and Collins growled at the cackling women who might break the leaders’ sleep.

All night long the looting continued. While Volunteers broke into a cycle shop for material for barricades, the crowds went about their own business, not so calmly but far more thoroughly, until early morning, when they went singing home to bed and left the city’s heart comparatively quiet.

Next day, Tuesday, was almost a repetition of the first. Above the Post Office women and children used the deserted street as a park in which to take their ease and compare their looted treasures. The rain came, they scooted for shelter, the Volunteers on the roof came down drenched; all over the city they shivered behind their barricades. Another fire began and roared skyward. All night, fire, fire! The sentries on the roof saw what seemed to be the end of their city.