Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

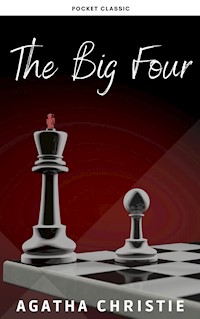

- Herausgeber: Pocket Classic

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Famed private eye Hercule Poirot tackles international intrigue and espionage in this classic Agatha Christie mystery. Framed in the doorway of Hercule Poirot's bedroom stands an uninvited guest, coated from head to foot in dust. The man stares for a moment, then he sways and falls. Who is he? Is he suffering from shock or just exhaustion? Above all, what is the significance of the figure 4, scribbled over and over again on a sheet of paper? Poirot finds himself plunged into a world of international intrigue, risking his life—and that of his "twin brother"—to uncover the truth.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 282

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Agatha Christie

THE BIG FOUR

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 — The Unexpected Quest

Chapter 2 — The Man from the Asylum

Chapter 3 — We Hear More About Li Chang Yen

Chapter 4 — The Importance of a Leg of Mutton

Chapter 5 — Disappearance of a Scientist

Chapter 6 — The Woman on the Stairs

Chapter 7 — The Radium Thieves

Chapter 8 — In the House of the Enemy

Chapter 9 — The Yellow Jasmine Mystery

Chapter 10 — We Investigate at Croftlands

Chapter 11 — A Chess Problem

Chapter 12 — The Baited Trap

Chapter 13 — The Mouse Walks In

Chapter 14 — The Peroxide Blonde

Chapter 15 — The Terrible Catastrophe

Chapter 16 — The Dying Chinaman

Chapter 17 — Number Four Wins a Trick

Chapter 18 — In the Felsenlabyrynth

About the Author

Chapter 1 — The Unexpected Quest

I have met people who enjoy a channel crossing; men who can sit calmly in their deck-chairs and, on arrival, wait until the boat is moored, then gather their belongings together without fuss and disembark. Personally, I can never manage this. From the moment I get on board I feel that the time is too short to settle down to anything.

I move my suitcases from one spot to another, and if I go down to the saloon for a meal I bolt my food with an uneasy feeling that the boat may arrive unexpectedly whilst I am below. Perhaps all this is merely a legacy from one’s short leaves in the war, when it seemed a matter of such importance to secure a place near the gangway, and to be amongst the first to disembark lest one should waste precious minutes of one’s three or five days’ leave.

On this particular July morning, as I stood by the rail and watched the white cliffs of Dover drawing nearer, I marvelled at the passengers who could sit calmly in their chairs and never even raise their eyes for the first sight of the native land. Yet perhaps their case was different from mine. Doubtless many of them had only crossed to Paris for the weekend, whereas I had spent the last year and a half on a ranch in the Argentine. I had prospered there, and my wife and I had both enjoyed the free and easy life of the South American continent, nevertheless it was with a lump in my throat that I watched the familiar shore draw nearer and nearer.

I had landed in France two days before, transacted some necessary business, and was now en route for London. I should be there some months—time enough to look up old friends, and one old friend in particular. A little man with an egg-shaped head and green eyes—Hercule Poirot! I proposed to take him completely by surprise. My last letter from the Argentine had given no hint of my intended voyage—indeed, that had been decided upon hurriedly as a result of certain business complications—and I spent many amused moments picturing to myself his delight and stupefaction on beholding me.

He, I knew, was not likely to be far from his headquarters.

The time when his cases had drawn him from one end of England to the other was past. His fame had spread, and no longer would he allow one case to absorb all his time. He aimed more and more, as time went on, at being considered a “consulting detective”—as much a specialist as a Harley Street physician. He had always scoffed at the popular idea of the human bloodhound who assumed wonderful disguises to track criminals, and who paused at every footprint to measure it.

“No, my friend Hastings,” he would say; “we leave that to Giraud and his friends. Hercule Poirot’s methods are his own. Order and method, and ‘the little grey cells.’ Sitting at ease in our own armchairs we see the things that these others overlook, and we do not jump to the conclusion like the worthy Japp.”

No; there was little fear of finding Hercule Poirot far afield. On arrival in London, I deposited my luggage at an hotel and drove straight on to the old address. What poignant memories it brought back to me! I hardly waited to greet my old landlady, but hurried up the stairs two at a time and rapped on Poirot’s door.

“Enter, then,” cried a familiar voice from within.

I strode in. Poirot stood facing me. In his arms he carried a small valise, which he dropped with a crash on beholding me.

“Mon ami, Hastings!” he cried. “Mon ami, Hastings!”

And, rushing forward, he enveloped me in a capacious embrace. Our conversation was incoherent and inconsequent. Ejaculations, eager questions, incomplete answers, messages from my wife, explanations as to my journey, were all jumbled up together.

“I suppose there’s someone in my old rooms?” I asked at last, when we had calmed down somewhat. “I’d love to put up here again with you.”

Poirot’s face changed with startling suddenness.

“Mon Dieu! but what a chance epouvantable. Regard around you, my friend.”

For the first time I took note of my surroundings. Against the wall stood a vast ark of a trunk of prehistoric design. Near to it were placed a number of suitcases, ranged neatly in order of size from large to small. The inference was unmistakable.

“You are going away?”

“Yes.”

“Where to?”

“South America.”

“What?”

“Yes, it is a droll farce, is it not? It is to Rio I go, and every day I say to myself, I will write nothing in my letters—but oh! The surprise of the good Hastings when he beholds me!”

“But when are you going?”

Poirot looked at his watch.

“In an hour’s time.”

“I thought you always said nothing would induce you to make a long sea voyage?”

Poirot closed his eyes and shuddered.

“Speak not of it to me, my friend. My doctor, he assures me that one dies not of it—and it is for the one time only; you understand, that never—never shall I return.”

He pushed me into a chair.

“Come, I will tell you how it all came about. Do you know who is the richest man in the world? Richer even than Rockefeller? Abe Ryland.”

“The American Soap King?”

“Precisely. One of his secretaries approached me. There is some very considerable, as you would call it, hocus-pocus going on in connection with a big company in Rio. He wished me to investigate matters on the spot. I refused. I told him that if the facts were laid before me, I would give him my expert opinion. But that he professed himself unable to do. I was to be put in possession of the facts only on my arrival out there. Normally, that would have closed the matter. To dictate to Hercule Poirot is sheer impertinence. But the sum offered was so stupendous that for the first time in my life I was tempted by mere money. It was a compettence—a fortune! And there was a second attraction—you, my friend. For this last year and a half I have been a very lonely old man. I thought to myself. Why not? I am beginning to weary of this unending solving of foolish problems. I have achieved sufficient fame. Let me take this money and settle down somewhere near my old friend.”

I was quite affected by this token of Poirot’s regard.

“So I accepted,” he continued, “and in an hour’s time I must leave to catch the boat train. One of life’s little ironies, is it not? But I will admit to you, Hastings, that had not the money offered been so big, I might have hesitated, for just lately I have begun a little investigation of my own. Tell me, what is commonly meant by the phrase, ‘The Big Four’?”

“I suppose it had its origin at the Versailles Conference, and then there’s the famous ‘Big Four’ in the film world, and the term is used by hosts of smaller fry.”

“I see,” said Poirot thoughtfully. “I have come across the phrase, you understand, under certain circumstances where none of those explanations would apply. It seems to refer to a gang of international criminals or something of that kind; only—”

“Only what?” I asked, as he hesitated.

“Only that I fancy that it is something on a large scale. Just a little idea of mine, nothing more. Ah, but I must complete my packing. The time advances.”

“Don’t go,” I urged. “Cancel your passage and come out on the same boat with me.”

Poirot drew himself up and glanced at me reproachfully.

“Ah, it is that you do not understand! I have passed my word, you comprehend—the word of Hercule Poirot. Nothing but a matter of life or death could detain me now.”

“And that’s not likely to occur,” I murmured ruefully. “Unless at the eleventh hour ‘the door opens and the unexpected guest comes in.’”

I quoted the old saw with a slight laugh, and then, in the pause that succeeded it, we both started as a sound came from the inner room.

“What’s that?” I cried.

“Ma foi!” retorted Poirot. “It sounds very like your ‘unexpected guest’ in my bedroom.”

“But how can anyone be in there? There’s no door except into this room.”

“Your memory is excellent, Hastings. Now for the deductions.”

“The window! But it’s a burglar, then? He must have had a stiff climb of it—I should say it was almost impossible.”

I had risen to my feet and was striding in the direction of the door when the sound of a fumbling at the handle from the other side arrested me.

The door swung slowly open. Framed in the doorway stood a man. He was coated from head to foot with dust and mud; his face was thin and emaciated. He stared at us for a moment, and then swayed and fell. Poirot hurried to his side, then he looked up and spoke to me.

“Brandy—quickly.”

I dashed some brandy into a glass and brought it. Poirot managed to administer a little, and together we raised him and carried him to the couch. In a few minutes he opened his eyes and looked round him with an almost vacant stare.

“What is it you want, monsieur?” said Poirot.

The man opened his lips and spoke in a queer mechanical voice.

“M. Hercule Poirot, 14 Farraway Street.”

“Yes, yes; I am he.”

The man did not seem to understand, and merely repeated in exactly the same tone: “M. Hercule Poirot, 14 Farraway Street.”

Poirot tried him with several questions. Sometimes the man did not answer at all; sometimes he repeated the same phrase. Poirot made a sign to me to ring up on the telephone.

“Get Dr. Ridgeway to come round.”

The doctor was in luckily; and as his house was only just round the corner, few minutes elapsed before he came bustling in.

“What’s all this, eh?”

Poirot gave a brief explanation, and the doctor started examining our strange visitor, who seemed quite unconscious of his presence or ours.

“Hm!” said Dr. Ridgeway, when he had finished. “Curious case.”

“Brain fever?” I suggested.

The doctor immediately snorted with contempt.

“Brain fever! Brain fever! No such thing as brain fever. An invention of novelists. No; the man’s had a shock of some kind. He’s come here under the force of a persistent idea—to find M. Hercule Poirot, 14 Farraway Street—and he repeats those words mechanically without in the least knowing what they mean.”

“Aphasia?” I said eagerly.

This suggestion did not cause the doctor to snort quite as violently as my last one had done. He made no answer, but handed the man a sheet of paper and a pencil.

“Let’s see what he’ll do with that,” he remarked.

The man did nothing with it for some moments, then he suddenly began to write feverishly. With equal suddenness he stopped and let both paper and pencil fall to the ground. The doctor picked it up, and shook his head.

“Nothing here. Only the figure 4 scrawled a dozen times, each one bigger than the last. Wants to write 14 Farraway Street, I expect. It’s an interesting case—very interesting. Can you possibly keep him here until this afternoon? I’m due at the hospital now, but I’ll come back this afternoon and make all arrangements about him. It’s too interesting a case to be lost sight of.”

I explained Poirot’s departure and the fact that I proposed to accompany him to Southampton.

“That’s all right. Leave the man here. He won’t get into mischief. He’s suffering from complete exhaustion. Will probably sleep for eight hours on end. I’ll have a word with that excellent Mrs. Funnyface of yours, and tell her to keep an eye on him.”

And Dr. Ridgeway bustled out with his usual celerity. Poirot hastily completed his packing, with one eye on the clock.

“The time, it marches with a rapidity unbelievable. Come now, Hastings, you cannot say that I have left you with nothing to do. A most sensational problem.The man from the unknown. Who is he? What is he? Ah, sapristi, but I would give two years of my life to have this boat go tomorrow instead of today. There is something here very curious—very interesting. But one must have time—time. It may be days—or even months—before he will be able to tell us what he came to tell.”

“I’ll do my best, Poirot,” I assured him. “I’ll try to be an efficient substitute.”

“Ye-es.”

His rejoinder struck me as being a shade doubtful. I picked up the sheet of paper.

“If I were writing a story,” I said lightly, “I should weave this in with your latest idiosyncrasy and call it The Mystery of the Big Four.” I tapped the pencilled figures as I spoke.

And then I started, for our invalid, roused suddenly from his stupor, sat up in his chair and said clearly and distinctly:

“Li Chang Yen.”

He had the look of a man suddenly awakened from sleep. Poirot made a sign to me not to speak. The man went on. He spoke in a clear, high voice, and something in his enunciation made me feel that he was quoting from some written report or lecture.

“Li Chang Yen may be regarded as representing the brains of the Big Four. He is the controlling and motive force. I have designated him, therefore, as Number One. Number Two is seldom mentioned by name. He is represented by an ‘S’ with two lines through it—the sign for a dollar; also by two stripes and a star. It may be conjectured, therefore, that he is an American subject, and that he represents the power of wealth. There seems no doubt that Number Three is a woman, and her nationality French. It is possible that she may be one of the sirens of the demi-monde, but nothing is known definitely. Number Four—”

His voice faltered and broke. Poirot leant forward.

“Yes,” he prompted eagerly. “Number Four?”

His eyes were fastened on the man’s face. Some overmastering terror seemed to be gaining the day; the features were distorted and twisted.

“The destroyer,” gasped the man. Then, with a final convulsive movement, he fell back in a dead faint.

“Mon Dieu!” whispered Poirot, “I was right then. I was right.”

“You think—?”

He interrupted me.

“Carry him on to the bed in my room. I have not a minute to lose if I would catch my train. Not that I want to catch it. Oh, that I could miss it with a clear conscience! But I gave my word. Come, Hastings!”

Leaving our mysterious visitor in the charge of Mrs. Pearson, we drove away, and duly caught the train by the skin of our teeth. Poirot was alternately silent and loquacious. He would sit staring out of the window like a man lost in a dream, apparently not hearing a word that I said to him. Then, reverting to animation suddenly, he would shower injunctions and commands upon me, and urge the necessity of constant marconigrams.

We had a long fit of silence just after we passed Woking. The train, of course, did not stop anywhere until Southhampton; but just here it happened to be held up by a signal.

“Ah! Sacré mille tonnerres!” cried Poirot suddenly. “But I have been an imbecile. I see clearly at last. It is undoubtedly the blessed saints who stopped the train. Jump, Hastings, but jump, I tell you.”

In an instant he had unfastened the carriage door, and jumped out on the line.

“Throw out the suitcases and jump yourself.”

I obeyed him. Just in time. As I alighted beside him, the train moved on.

“And now Poirot,” I said, in some exasperation, “perhaps you will tell me what all this is about.”

“It is, my friend, that I have seen the light.”

“That,” I said, “is very illuminating to me.”

“It should be,” said Poirot, “but I fear—I very much fear that it is not. If you can carry two of these valises, I think I can manage the rest.”

Chapter 2 — The Man from the Asylum

Fortunately the train had stopped near a station. A short walk brought us to a garage where we were able to obtain a car, and half an hour later we were spinning rapidly back to London. Then, and not till then, did Poirot deign to satisfy my curiosity.

“You do not see? No more did I. But I see now. Hastings, I was being got out of the way.”

“What!”

“Yes. Very cleverly. Both the place and the method were chosen with great knowledge and acumen. They were afraid of me.”

“Who were?”

“Those four geniuses who have banded themselves together to work outside the law. A Chinaman, an American, a Frenchwoman, and—another. Pray the good God we arrive back in time, Hastings.”

“You think there is danger to our visitor?”

“I am sure of it.”

Mrs. Pearson greeted us on arrival. Brushing aside her ecstasies of astonishment on beholding Poirot, we asked for information. It was reassuring. No one had called, and our guest had not made any sign.

With a sigh of relief we went up to the rooms. Poirot crossed the outer one and went through to the inner one.

Then he called me, his voice strangely agitated.

“Hastings, he’s dead.”

I came running to join him. The man was lying as we had left him, but he was dead, and had been dead some time. I rushed out for a doctor. Ridgeway, I knew, would not have returned yet. I found one almost immediately, and brought him back with me.

“He’s dead right enough, poor chap. Tramp you’ve been befriending, eh?”

“Something of the kind,” said Poirot evasively. “What was the cause of death, doctor?”

“Hard to say. Might have been some kind of fit. There are signs of asphyxiation. No gas laid on, is there?”

“No, electric light—nothing else.”

“And both windows wide open, too. Been dead about two hours, I should say. You’ll notify the proper people, won’t you?”

He took his departure. Poirot did some necessary telephoning. Finally, somewhat to my surprise, he rang up our old friend Inspector Japp, and asked him if he could possibly come round.

No sooner were these proceedings completed than Mrs. Pearson appeared, her eyes as round as saucers.

“There’s a man here from ‘Anwell—from the ‘Sylum. Did you ever? Shall I show him up?”

We signified assent, and a big burly man in uniform was ushered in.

“‘Morning, gentlemen,” he said cheerfully. “I’ve got reason to believe you’ve got one of my birds here. Escaped last night, he did.”

“He was here,” said Poirot quietly.

“Not got away again, has he?” asked the keeper, with some concern.

“He is dead.”

The man looked more relieved than otherwise.

“You don’t say so. Well, I dare say it’s best for all parties.”

“Was he—dangerous?”

“‘Omicidal, d’you mean? Oh, no. ‘Armless enough. Persecution mania very acute. Full of secret societies from China that had got him shut up. They’re all the same.”

I shuddered.

“How long had he been shut up?” asked Poirot.

“A matter of two years now.”

“I see,” said Poirot quietly. “It never occurred to anybody that he might—be sane?”

The keeper permitted himself to laugh.

“If he was sane, what would he be doing in a lunatic asylum? They all say they’re sane, you know.”

Poirot said no more. He took the man in to see the body. The identification came immediately.

“That’s him—right enough,” said the keeper callously; “funny sort of bloke, ain’t he? Well, gentlemen, I had best go off now and make arrangements under the circumstances. We won’t trouble you with the corpse much longer. If there’s an inquest, you will have to appear at it, I dare say. Good morning, sir.”

With a rather uncouth bow he shambled out of the room.

A few minutes later Japp arrived. The Scotland Yard Inspector was jaunty and dapper as usual.

“Here I am Moosior Poirot. What can I do for you? Thought you were off to the coral strands of somewhere or other today?”

“My good Japp, I want to know if you have ever seen this man before.”

He led Japp into the bedroom. The inspector stared down at the figure on the bed with a puzzled face.

“Let me see now—he seems sort of familiar—and I pride myself on my memory, too. Why, God bless my soul, it’s Mayerling!”

“And who is—or was—Mayerling?”

“Secret Service chap—not one of our people. Went to Russia five years ago. Never heard of again. Always thought the Bolshies had done him in.”

“It all fits in,” said Poirot, when Japp had taken his leave, “except for the fact that he seems to have died a natural death.”

He stood looking down on the motionless figure with a dissatisfied frown. A puff of wind set the window-curtains flying out, and he looked up sharply.

“I suppose you opened the windows when you laid him down on the bed, Hastings?”

“No, I didn’t,” I replied. “As far as I remember, they were shut.”

Poirot lifted his head suddenly.

“Shut—and now they are open. What can that mean?”

“Somebody came in that way,” I suggested.

“Possibly,” agreed Poirot, but he spoke absently and without conviction. After a minute or two he said: “That is not exactly the point I had in mind, Hastings. If only one window was open it would not intrigue me so much. It is both windows being open that strikes me as curious.”

He hurried into the other room.

“The sitting room window is open, too. That also we left shut. Ah!”

He bent over the dead man, examining the corners of the mouth minutely. Then he looked up suddenly.

“He has been gagged, Hastings. Gagged and then poisoned.”

“Good heavens!” I exclaimed, shocked. “I suppose we shall find out all about it from the post-mortem.”

“We shall find out nothing. He was killed by inhaling strong prussic acid. It was jammed right under his nose. Then the murderer went away again, first opening all the windows. Hydrocyanic acid is exceedingly volatile, but it has a pronounced smell of bitter almonds. With no trace of the smell to guide them, and no suspicion of foul play, death would be put down to some natural cause by the doctors. So this man was in the Secret Service, Hastings. And five years ago he disappeared in Russia.”

“The last two years he’s been in the Asylum,” I said. “But what of the three years before that?”

Poirot shook his head, and then caught my arm.

“The clock, Hastings, look at the clock.”

I followed his gaze to the mantelpiece. The clock had stopped at four o’clock.

“Mon ami, someone has tampered with it. It had still three days to run. It is an eight-day clock, you comprehend?”

“But what should they want to do that for? Some idea of a false scent by making the crime appear to have taken place at four o’clock?”

“No, no; rearrange your ideas, mon ami. Exercise your little grey cells. You are Mayerling. You hear something, perhaps—and you know well enough that your doom is sealed. You have just time to leave a sign. Four o’clock, Hastings. Number Four, the destroyer. Ah! an idea!”

He rushed into the other room and seized the telephone. He asked for Hanwell.

“You are the Asylum, yes, I understand there has been an escape today? What is that you say? A little moment, if you please. Will you repeat that? Ah! parfaitement.”

He hung up the receiver, and turned to me.

“You heard, Hastings? There has been no escape.”

“But the man who came—the keeper?” I said.

“I wonder—I very much wonder.”

“You mean—?”

“Number Four—the destroyer.”

I gazed at Poirot dumbfounded. A minute or two after, on recovering my voice, I said:

“We shall know him again, anywhere, that’s one thing. He was a man of very pronounced personality.”

“Was he, mon ami! I think not. He was burly and bluff and red-faced, with a thick moustache and a hoarse voice. He will be none of those things by this time, and for the rest, he has nondescript eyes, nondescript ears, and a perfect set of false teeth. Identification is not such an easy matter as you seem to think. Next time—”

“You think there will be a next time?” I interrupted.

Poirot’s face grew very grave.

“It is a duel to the death, mon ami. You and I on the one side, the Big Four on the other. They have won the first trick; but they have failed in their plan to get me out of the way, and in the future they have to reckon with Hercule Poirot!”

Chapter 3 — We Hear More About Li Chang Yen

For a day or two after our visit from the fake Asylum attendant I was in some hopes that he might return, and I refused to leave the flat even for a moment. As far as I could see, he had no reason to suspect that we had penetrated his disguise. He might, I thought, return and try to remove the body, but Poirot scoffed at my reasoning.

“Mon ami,” he said, “if you wish you may wait in to put salt on the little bird’s tail, but for me I do not waste my time so.”

“Well then, Poirot,” I argued, “why did he run the risk of coming at all. If he intended to return later for the body, I can see some point in his visit. He would at least be removing the evidence against himself; as it is, he does not seem to have gained anything.”

Poirot shrugged his most Gallic shrug. “But you do not see with the eyes of Number Four, Hastings,” he said. “You talk of evidence, but what evidence have we against him? True, we have a body, but we have no proof even that the man was murdered—prussic acid, when inhaled, leaves no trace. Again, we can find no one who saw anyone enter the flat during our absence, and we have found out nothing about the movements of our late friend, Mayerling...”

“No, Hastings, Number Four has left no trace, and he knows it. His visit we may call a reconnaissance. Perhaps he wanted to make quite sure that Mayerling was dead, but more likely, I think, he came to see Hercule Poirot, and to have speech with the adversary whom alone he must fear.”

Poirot’s reasoning appeared to me typically egotistical, but I forbore to argue.

“And what about the inquest?” I asked. “I suppose you will explain things clearly there, and let the police have a full description of Number Four.”

“And to what end? Can we produce anything to impress a coroner’s jury of your solid Britishers? Is our description of Number Four of any value? No; we shall allow them to call it ‘Accidental Death,’ and may be, although I have not much hope, our clever murderer will pat himself on the back that he deceived Hercule Poirot in the first round.”

Poirot was right as usual. We saw no more of the man from the asylum, and the inquest, at which I gave evidence, but which Poirot did not even attend, aroused no public interest.

As, in view of his intended trip to South America, Poirot had wound up his affairs before my arrival, he had at this time no cases on hand, but although he spent most of his time in the flat I could get little out of him. He remained buried in an armchair, and discouraged my attempts at conversation.

And then one morning, about a week after the murder, he asked me if I would care to accompany him on a visit he wished to make. I was pleased, for I felt he was making a mistake in trying to work things out so entirely on his own, and I wished to discuss the case with him. But I found he was not communicative. Even when I asked where we were going, he would not answer.

Poirot loves being mysterious. He will never part with a piece of information until the last possible moment. In this instance, having taken successively a bus and two trains, and arrived in the neighbourhood of one of London’s most depressing southern suburbs, he consented at last to explain matters.

“We go, Hastings, to see the one man in England who knows most of the underground life of China.”

“Indeed! Who is he?”

“A man you have never heard of—a Mr. John Ingles. To all intents and purposes, he is a retired Civil Servant of mediocre intellect, with a house full of Chinese curios with which he bores his friends and acquaintances. Nevertheless, I am assured by those who should know that the only man capable of giving me the information I seek is this same John Ingles.”

A few moments more saw us ascending the steps of The Laurels, as Mr. Ingles’s residence was called. Personally, I did not notice a laurel bush of any kind, so deduced that it had been named according to the usual obscure nomenclature of the suburbs.

We were admitted by an impassive-faced Chinese servant and ushered into the presence of his master. Mr. Ingles was a squarely-built man, somewhat yellow of countenance, with deep-set eyes that were oddly reflective in character. He rose to greet us, setting aside an open letter which he had held in his hand. He referred to it after his greeting.

“Sit down, won’t you? Halsey tells me that you want some information and that I may be useful to you in the matter.”

“That is so, monsieur. I ask of you if you have any knowledge of a man named Li Chang Yen?”

“That’s rum—very rum indeed. How did you come to hear about the man?”

“You know him, then?”

“I’ve met him once. And I know something of him—not quite as much as I should like to. But it surprises me that anyone else in England should even have heard of him. He’s a great man in his way—mandarin class and all that, you know—but that’s not the crux of the matter. There’s good reason to suppose that he’s the man behind it all.”

“Behind what?”

“Everything. The worldwide unrest, the labour troubles that beset every nation, and the revolutions that break out in some. There are people, not scaremongers, who know what they are talking about, and they say that there is a force behind the scenes which aims at nothing less then the disintegration of civilisation. In Russia, you know, there were many signs that Lenin and Trotsky were mere puppets whose every action was dictated by another’s brain. I have no definite proof that would count with you, but I am quite convinced that this brain was Li Chang Yen’s.”

“Oh, come,” I protested, “isn’t that a bit farfetched? How would a Chinaman cut any ice in Russia?”

Poirot frowned at me irritably.

“For you, Hastings,” he said, “everything is farfetched that comes not from your own imagination; for me, I agree with this gentleman. But continue, I pray, monsieur.”

“What exactly he hopes to get out of it all I cannot pretend to say for certain,” went on Mr. Ingles; “but I assume his disease is one that has attacked great brains from the time of Akbar and Alexander to Napoleon—a lust for power and personal supremacy. Up to modern times armed force was necessary for conquest, but in this century of unrest a man like Li Chang Yen can use other means. I have evidence that he has unlimited money behind him for bribery and propaganda, and there are signs that he controls some scientific force more powerful than the world has dreamed of.”