3,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

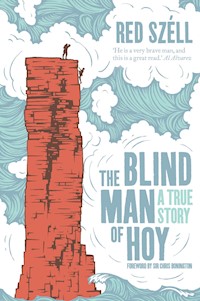

From the moment I watched a documentary of Chris Bonington and Tom Patey climb the perpendicular flanks of the Old Man of Hoy I knew that my life would not be complete until I had followed in their footholds. That was in 1983 when I was thirteen. Within months I was tackling my first crags and dreaming of standing atop Europe's tallest sea stack with the Atlantic pounding 450 feet below. Those dreams went dark at nineteen when I learned I was going blind. I hung up my harness for twenty years and tried to ignore the twinge of desire I felt every time The Old Man appeared on TV.' Middle aged, by now a family man, crime novelist and occasional radio personality, Red Szell's life nonetheless felt incomplete. He was still climbing, but only indoors until he shared his old, unforgotten, dream with his buddies, Matthew and Andres, and it became obvious that an attempt had to be made. With the help of mountain guides Martin Moran and Nick Carter, and adventure cameraman Keith Partridge, supported by family and an ever growing following, Red set out to confront the Orcadian giant.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Born in 1969, Redmond Széll grew up in rural West Sussex on a diet of classic adventure and crime stories. After studying English at Cambridge and a brief spell working as a mortuary porter he moved to London to pursue a career in journalism. A stay-at-home dad since the first of his two daughters was born in 2000 he divides his time between writing, climbing and housework.

Also by this author

Blind Trust

THE BLIND MAN OF HOY

Red Széll

First published in Great Britain

and the United States of America

Sandstone Press Ltd

Dochcarty Road

Dingwall

Ross-shire

IV15 9UG

Scotland.

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

© Redmond Széll 2015

Foreword © Chris Bonington 2015

Editor: Robert Davidson

Photo section: Heather MacPherson

Technical assistance: David Ritchie

Proof: Roger Smith

The moral right of Redmond Szell to be recognised as the

author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act, 1988.

The table in Appendix 2 is reproduced by permission of Rockfax.

© Rockfax 2002, 2008 – www.rockfax.com

The publisher acknowledges subsidy from Creative Scotland towards publication of this volume.

ISBN: 978-1-910124-22-2

ISBNe: 978-1-910124-23-9

Cover design by David Wardle at Bold and Noble

Ebook by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore

To Matthew for faith, forthrightness and friendship

Contents

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Foreword by Sir Chris Bonington

Fact File

1. Facing Up

2. Getting Off

3. Formation and Partial Collapse

4. Breaking Out of Solitary

5. Gearing Up

6. The Cole Styron Workout – Part 1

7. Al Alvarez

8. The Cole Styron Workout – Part 2

9. Crack Team

10. Seeking Professional Help

11. Highland Fling

12. The Diff to End all Diffs

13. Down to Earth

14. Out-of-Touch and In-Touch

15. Peak Practice

16. Buffing Up

17. Day 1, Journey to Hoy

18. Day 2, All Talk, No Action

19. Day 3, First Ascent of the Old Man by a Blind Man

20. Day 4, Take Two

21. Touchdown

22. What Goes Up

Appendix A: Glossary of some of the more commonly used rock climbing terms

Appendix B: Rockfax Climbing Grade Table

List of Illustrations

1. Red at Swiss Cottage climbing wall (photo: Matthew Wootliff)

2. A guiding hand from Matthew (photo: Andres Cervantes)

3. Martin leading off Cioch Nose, note the climbing shoes and the rocky ground! (photo: Alex Moran)

4. Route Three, Diabaig (photo: Martin Moran)

5. Crack climbing using the elevator door technique at Latheronwheel (photo: Nick Carter)

6. Red, Keith, Andres & Martin on the ferry to Stromness (photo: Matthew Wootliff)

7. Hoy’s dramatic coastline bathed in perfect evening light, from the ferry (photo: Keith Partridge)

8. The long walk-in, the Old Man in the distance (photo: Nick Carter)

9. Having got him kitted out for the climb, Red’s entourage tries to convince him that the Old Man doesn’t look so big . . . from the promontory (photo: Keith Partridge)

10. The long and precipitous descent down the cliff (photo: Matthew Wootliff)

11. The route (photo: Mike Lee, art: Jim Buchanan)

12. Nick jumaring just above Red (photo: Martin Moran)

13. The Crux Pitch (photo: Keith Partridge)

14. Nick jumaring just above Red at The Coffin (photo: Martin Moran)

15. Red exiting The Coffin (photo: Keith Partridge)

16. Keith and Andres filming the climb (photo: Matthew Wootliff)

17. It’s a long way down and a long way up and it’s steep rock all the way (photo: Keith Partridge)

18. Approaching the sanctuary of the second belay stance (photo: Keith Partridge)

19. A quick rest before the final pitch (photo: Nick Carter)

20. Near the summit there’s a cleft through the rock as if some giant had taken an axe to the summit (photo: Keith Partridge)

21. Rock Gods: Nick, Martin & Red at the summit (photo: Keith Partridge)

22. Signing the log book at the summit (photo: Nick Carter)

23. Abseiling off – Red and Martin (photo: Keith Partridge)

24. Nick abseiling in midair (photo: Keith Partridge)

25. Friends reunited (photo: Nick Carter)

26. Red during cliff-top interview with Keith (photo: Keith Partridge)

Acknowledgements

None of this would have been possible without a small army of very supportive and selfless people who gave help, encouragement, time, equipment, advice and expertise freely and without much of the grumbling they often received in return from me. Thank you all!

Andres and Cole without whose supreme efforts I would never have made it past the first pitch; and Dan, Isabel, Jimena, Matt and Trevor who, like everyone at Climb London, provided excellent, professional training with boundless patience. I am especially indebted to Paul Ackland of High Sports for giving me free access to all the CL walls. Also Rob and Tom at Mammut for kitting me out for the climb.

Peter, Lee, Cheryl and the many listeners to In Touch whose support was so vital in making this adventure more than just a personal undertaking and who, like Steve Bate, reminded me that I am part of a community.

David Head and all at RP Fighting Blindness for running the donations side and being that rare thing, a representative charity in a world of careerist fundraisers.

Omri for designing the webpage and keeping people posted.

Piers, Poh Sim, Al and Anne for wise counsel, delicious tea, poetry and nudging me in the direction of Highgate ponds. And The EGLST (Tom in particular) for persuading me to take the plunge.

Meg Wickes at Triple Echo and Keith Partridge for giving me the best holiday video ever!

Martin and Nick for having confidence in my abilities and for getting me to the summit and back again safely and, like Keith, Matthew and Andres being kind enough to allow me to reproduce their excellent photos.

Bill, Hannah and particularly Dad for braving the first draft of the book. Carl and Tom Bauer for de-chossing the glossary and Alan James at Rockfax for allowing me to reproduce his excellent table explaining the arcana of route grading.

Robert Davidson at Sandstone Press for believing in this story and making it better with his thoughtful editing.

Last but by no means least Kate, Laura and Megan for their unfaltering love and for putting up with my black moods and press-ups at breakfast.

Foreword

‘After we gave up our attempt on the South West Face of Everest in November 1972, I remember saying to Chris Brasher who had come out to Base Camp to report our story for The Observer: “Climbing is all about gambling. It’s not about sure things. It’s about challenging the impossible. I think we have found that the South West Face of Everest in the post-monsoon period is impossible!” Rash words for, of course, the story of mountaineering has proven time and again that there is no such thing as impossible.’

Those words are taken from the first chapter of a book I wrote as long ago as 1976, Everest the Hard Way, after a second attempt with a new team had succeeded in the same ‘impossible’ mission. On that occasion we put four climbers on the summit, Dougal Haston, Doug Scott, Peter Boardman and Pertemba Sherpa, and possibly a fifth in Mick Burke who did not return. Teamwork had been of the essence as it is on all expeditions.

Ten years before the publication of that book I joined Tom Patey and Rusty Bailie to climb the Old Man of Hoy for the first time, repeating the following year on one of the BBC’s first major outside broadcasts. Again, on both occasions, teamwork was of the essence.

These thoughts are prompted by reading Red Széll’s vivid and moving account of the first successful ascent of the Old Man of Hoy by a registered blind climber. Before his great achievement many people would have regarded such a feat as impossible. Again though, teamwork was of the essence, and the team that Red put together of professional climbers Martin Moran and Nick Carter, Keith Partridge, who is probably the world’s leading adventure cameraman, and Red’s two friends Andres Cervantes and Matthew Wootliff, proved to be a sound one. There is a wider team whom the author has properly credited in his Acknowledgements.

History tells us that when the impossible has been achieved it is likely to be repeated in short order. No doubt this will be as true of Red’s ascent of the Old Man ‘the hard way’ as it was after Hillary and Tensing’s first ascent of Everest, and it will similarly be repeated. There is something special about being the first though, about being the one who steps forward and says: ‘Can’t be done? I’ll show ya’!’

Red’s climb, and the excellent book he has written about it, are lyrical and inspiring. They attest to the need for challenge and the value of comradeship. In adversity there is solidarity and behind the dark curtain that Retinitis Pigmentosa has thrown over his eyes there still shines a light. Red climbs because he is a climber as are few people and in that fact lies a mystery which I feel we must let rest. Some can’t, some must, but there is no such thing as impossible.

Sir Chris Bonington CVO CBE DL

The Old Man of Hoy Fact File

It is located off Hoy, second largest of the Orkney Islands, Scotland

It is a pillar of Old Red Sandstone standing on a plinth of igneous basalt

It stands 449 feet (137 metres) high

It was formed by the sea eroding the cliff it was once part of

Though the rock it’s made of is over 500 million years old, the stack itself has stood for less than 400 years.

The same erosion that formed it could topple it at any time

It was first climbed in 1966, 13 years after Everest, by (now Sir) Chris Bonington, Tom Patey and Rusty Baillie

In 1967 an estimated 15 million people watched

The Big Climb

, a live broadcast by the BBC following an elite group of climbers (including Bonington and Patey) as they tackled the Old Man via three different routes.

Usually the stack is climbed in five sections, or pitches, and descended in three abseils

The Old Man of Hoy appears both in an episode of Monty Python and in the video to ‘Here Comes the Rain Again’ by the Eurythmics

In 2013 Red Széll attempted to become the first blind person to make the climb, the subject of this book

‘We see with our brain not with our eyes’

– Paul Bach-y-Rita quoted in

The Brain That Changes Itself by Norman Doidge

1 Facing Up

‘The Old Man of Hoy – 450 feet of crumbling sandstone rock rising out of the North Atlantic off the islands of Orkney . . . the most awesome pinnacle in the British Isles.’

– Chris Brasher, The Big Climb

June 2013

Nothing can prepare you for coming face to face with the Old Man of Hoy.

For months I’d glibly told people that I was going to climb this sea stack roughly the shape and size of the Gherkin. From the top of the promontory it was once the tip of, the Old Man hadn’t appeared too intimidating, but with each precarious step down the shattered cliff it had loomed larger, so by the time I was standing on the rockfall causeway that used to form its mighty arch, the giant’s stated height looked to be an underestimate.

As a teenager in the mid-1980s I’d watched Chris Bonington and Joe Brown scale this perpendicular monolith in a documentary about The Big Climb (the BBC’s epic live coverage of their 1967 ascent) and thought, ‘I want to do that’.

Within a year I’d found a way to go rock-climbing through school and got hooked.

Aged 19 I’d discovered I was going blind. It was like taking a long fall and wondering whether the person belaying was ever going to stop the rope. After a brief battle I’d hung up my harness for the best part of 20 years and tried to ignore the cravings.

What vision I have left now is like looking into a smoke-filled room through a keyhole – I catch glimpses of parts of things. If they lie at the lower end of the colour spectrum and stay still long enough, I sometimes stand a chance of identifying what they are. The red Orcadian sandstone ahead of me was the colour of dried blood and as unlikely to move. I took it in in stages – a lot of stages.

Martin Moran, the mountain guide who was leading this climb, set off first, the protection (the metal wedges and bolts he’d insert at intervals into cracks in the rock and through which he’d run the rope to catch him should he fall) jangling at his belt like wind chimes. I followed their progress, trying to visualise the line he was taking. After quarter of an hour he stopped and shortly thereafter I felt three tugs on my rope, the signal he was ready for me to follow.

The rock was cold and damp. I explored it with my fingers, testing its slowly decaying strength, before settling on a couple of firm holds. Sea birds wheeled overhead, surfing the light southerly breeze. I took a deep breath, grimaced at Keith the cameraman and stepped up to the first ledge. Only another 444 feet to go. Oh, and the overhanging crux. And all of it being recorded for posterity by TV and radio!

If dreams can be planned, this one had got a bit out of hand. My simple wish to emulate Bonington and Brown had gone awry the moment I’d received my diagnosis, but should this attempt at dream-fulfilment turn into a nightmare it would be with national coverage and everlasting documentary proof.

2 Getting Off

‘Much of what goes by the name of pleasure is simply an effort to destroy consciousness.’

– George Orwell

December 2012

It’s the week before Christmas and I’ve just knocked back my fifth glass of Rioja on top of at least three glasses of champagne. The hostess is chattering away but my attention is more focussed on the silk-clad breast pressing insistently against my forearm. Its owner, one of the mums from my younger daughter’s class, is becoming tipsily affectionate. I accept another glass from a passing waitress, swig it down in two gulps and wait for it to numb my sense of dislocation.

I’m not in a good place. Sure the party’s great; I’m among friends, happily married with two delightful daughters, but inside there’s this constant, leaded ache that poisons my thoughts and refuses to recede.

I knock back another glass and wish that people still smoked at the parties I get invited to. Oh-oh, bladder calling. Maybe I should ask the affectionate yummy mummy to help me downstairs to the loo; who knows what might happen?

Something snaps and snarls: ‘You’re beginning to sound like Joe Wynde and he’s such a useless, dysfunctional prick he can’t even nail his second case!’

For the past seven months I’ve sat staring into space trying to bludgeon the plot of the sequel to my debut crime novel into something worth submitting for publication. Joe Wynde, my protagonist, may share several of my outward characteristics including visual impairment, but his morbid sense of loss allows him to cross lines I only feel comfortable approaching in fiction. Blind as I am, I could never look my wife and daughters in the eye otherwise.

A year and a half ago, when Blind Trust had been published, I’d thought at last I’d found a way of harnessing, if not taming, my depression. I’d made it past base camp in the writing world, and with moderately good sales and an audiobook version in my rucksack was well equipped to climb further, but with my new plot tangled and knotted it seems now I’m just left with a longer drop back down.

The waitress has refilled my glass. I lean back into a pillar, away from temptation, and take another swig. Painkiller/ time-killer: I’ve been doing this with one substance or another for more than half my life, only of late the quantities and frequency have been increasing. It’s boring, I’m boring – I’m bored.

I’m in a rut, which as some wag once pointed out, is just an endless coffin. Time to climb out.

A familiar raucous laugh guides me across the room. Swaying slightly I wait for a break in the conversation. All of a sudden I feel good; positive and pain-free; relaxed and ready.

‘Evening Mr Szell, you look like you’re having a good time.’ As ever the ambiguity is there, like a boxer’s dance before he gets stuck in.

‘Hey, Matthew. Fuck it, I give in. Let’s do it. Let’s climb the bastard.’

‘Really?’ That wrong-footed him, though he’s still wary. Hardly surprising after my prevarication.

‘Yes, really! I want to give it a go – climb the Old Man of Hoy this summer – definitely.’

‘Fucking yes! Brilliant! That’s great.’ And he’s slapping me on the back and my glass gets refilled and this time I knock it back in celebration.

‘What made you decide to say yes at last?’ he asks a few minutes later, after we’ve explained the commotion to some stunned fellow guests who I suspect think it’s the wine talking.

I hesitate. I trust Matthew enough to climb with him, I’m even beginning to consider him a friend but . . . on a need to know basis?

‘Oh, you know, I’ve been mulling it over and you’re right, if I don’t say yes now we lose another year and then it’ll only be more difficult. So yeah, let’s do it!’

Someone who did need to know, the decision if not the process by which it had been reached, is my wife Kate. She is somewhat surprised when Matthew informs her.

Shortly thereafter she and I leave the party and a room of people wondering whether my bravado will survive the cold light of day.

3 Formation and Partial Collapse

‘Why climb? For the natural experience; for the danger that draws us ever on; for the feeling of total freedom; for the monstrous drop beneath you. It is like a drug’

– Hermann Buhl.

According to my mother I began climbing to escape boredom and inertia at an early age, learning to scale the sides of my cot and mastering the downward traverse to my toy-box before I was a year old.

As I grew up I emulated Spiderman’s vertical ascents on every available play-frame, tree or building and watched John Noakes’ exploits with a mixture of awe and envy. Blue Peter also introduced me to the great mountaineering feats of the 1970s and 80s and I followed the expeditions goggle-eyed on the BBC. The death of Nick Estcourt on K2 had a greater impact on me than that of Elvis a few months earlier.

Chris Bonington had become a familiar figure from all his media work, but it was the simultaneous appearance of Joe Brown and the Old Man of Hoy on my TV screen in about 1984 that convinced me I could take my love of climbing to another level. Bonington was a larger-than-life gentleman-adventurer type but Brown came across as an ordinary bloke, a Manchester plumber. And the Old Man was a rock cathedral summoning the faithful that, in comparison to the mountaineering meccas of Annapurna and Everest, lay on my doorstep.

This form of climbing looked extremely accessible.

Rural Sussex is not renowned for its crags and peaks but the school’s Cadet Force promised a summer camp in the Brecon Beacons that included a couple of days rock climbing training with the Army; so I signed up and suffered a year’s square-bashing as my fee.

The course was so good that I stayed in the Cadets for another two years by the end of which both my climbing and marching were pretty sound, before escaping to the sixth form rock club with its twice-termly trips to Harrison’s Rocks in Kent. I was hooked.

At university I bypassed the Mountaineering Club, my recollection is that they were too Alpine for my taste and pocket, preferring the buttresses, slates and parapets of Cambridge’s roofline instead.

The company was good, the protection minimal if there at all. Perhaps it is as well that access to the window ledge necessary to complete The Senate House Leap (The K2 of Cambridge Night-Climbing, requiring the traverse of an 8ft wide void 70ft above the cobbles) was barred by the occupancy of a responsible adult in the room beyond.

My nights out on the tiles were numbered anyway. In September 1989, shortly before my 20th birthday, I was somewhat bluntly informed by a consultant ophthalmologist that I was suffering from Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) and ‘could expect to be ’effectively blind by the age of 30’.

RP is a degenerative eye condition that affects the photoreceptors at the back of the eye. First the rods, responsible in the main for night and peripheral vision die off, followed by the cones and their colour vision. If you’re lucky the bundle of cells that form the macular and are responsible for central vision hang around for a few years but they too are on borrowed time.

Back in 1989 I was still in the early stages. My field of vision had only decreased by about a quarter of the standard 95 degrees and I had yet to experience the joys of photopsia (the constant kaleidoscope of flashing lights that burst across my vision as my brain tries to fill in the gaps left by my increasingly dead retina).

Climbing, however, is all about trust. If I could no longer trust my own abilities how could I expect anyone else to want to climb with me? At the same time though, more than ever, I needed the release; I needed to feel in balance with myself.

I began to push my luck. Night-climbing in states of Dutch courage that make me cringe for my safety now (bear in mind it was a lack of night-vision that had got me referred to the consultant in the first place) to prove to myself that I could beat the condition.

My favourite ascent, of the North East face of the Fitzwilliam Museum, topped out at a glorious glass cupola where I could enjoy a spliff before my descent. Maybe this is why I can remember so little of the English Literature I was meant to be reading at the time. Certainly being too wasted to be scared stiff saved me from serious injury on the couple of occasions I took nasty, unprotected falls.

Eventually the will to live and a realisation that I was fighting a losing battle grounded me and, if truth be told at least where climbing is concerned, I went into a two decade sulk.

One by one the other sports I enjoyed followed: first cycling, then cross- country and rugby. Substituting them with a rowing machine, swimming and Pilates I continued to keep relatively fit, but these new activities never succeeded in allowing me to vent the frustration I felt at being disabled from pushing myself to my physical limits. And the will to climb smouldered away in the background, reignited regularly by TV documentaries and films like Touching the Void.

I’d tried a couple of climbing centres in the 1990s but they had been more focussed on bouldering so didn’t satisfy my need to get high at the end of a rope. Consequently when in 2009 my elder daughter announced that she wanted to hold her 9th birthday party at Climb London in Swiss Cottage I wasn’t expecting much. How wrong could I have been?

According to a couple of the dads who’d stayed to help, the two South American instructors running the party were ‘very tasty.’ I too had started drooling on arrival but for another reason entirely. During the 90-minute session I had ample opportunity to check out the 18 purpose-built walls with their multiple routes. They ranged from simple 75 degree 10m-high slabs to a sparsely featured 14.5m overhanging monster. I left feeling my eyes had been opened to a world of new possibilities.

If the staff at Climb London in Swiss Cottage were surprised to receive a new client brandishing a white stick they certainly never expressed it. Rather, as the weeks went by and we got to know each other, they treated it as a challenge that would result in them becoming better teachers and me climbing outdoors again – which of course is where all true climbers should want to be. I was happy to start from scratch; much of the equipment had been updated anyway and two decades of beer and curry weighed heavily on my agility.

Trevor, my first instructor is an old trad climbing hand who works to pay for his crag habit. He worked patiently with me, offering encouragement as I rebuilt my confidence and stamina with a series of Rambo-style assaults on the easier routes, then chatting amiably about great places to climb as I gasped for breath in recovery.

Gradually he began to remind me that by employing skill and technique I could conserve energy and tackle more difficult routes. As the months passed, the prospect of getting out onto rock again became less absurd, until one day as I lay gasping but jubilant having just conquered a tricky overhanging problem and Trevor was waxing lyrical about coastal climbing, I confided my dream of scaling the Old Man of Hoy.

The dream had never died, just gone into suspended animation to be galvanised whenever I saw an advert for the Scottish Tourist Board or watched an episode of Coast. Like the summer romance I never quite had with a school-friend’s older sister, it was cheering to bathe in thoughts of what might have been.

Trevor rubbed his chin and in his calm, considered way said, ‘well . . . it’s only an HVS . . . with a bit of work you could probably manage it.’

For the next couple of years that was enough. I was content to know that my dream wasn’t completely untenable and it remained, a distant goal to work towards. I made slow but pleasing progress, which was a happy counterpoint to my fast degenerating eyesight.

I don’t think that I or anyone at home or Climb London really expected me to try to make the dream become reality, but then none of us had anticipated the intervention of Matthew Wootliff.

Matthew had been among the first of the existing parents to introduce themselves when my daughters started school. A sinewy blend of Leeds forthrightness and North West London chutzpah he worked from home and often did the school run. He was also equipped with a voice and laugh that made it easy for me to locate him in the crowd, no matter how close to twilight it was.

In the 13 years I’ve been one I’m still the only full-time house-husband I’ve ever met, so it was good to have another dad to talk to; even more so when we turned out to be the only male representatives on the PTA. However, although both pairs of our daughters were in the same forms, neither was best friends. So Matthew and I met mostly briefly, at school functions or in the twice-daily tidal flow through the gates and, like our children, got on well-enough without knowing each other that well.

Over five years I’d got an inkling of the streak of dogged determination in him; enough that when I mentioned I was a regular at the climbing wall and he expressed interest, I was kicking myself even as I suggested he join me.

This was my activity, my time away from my fellow parents and Hampstead neighbours (some of whom were one and the same) – my little bit on the side that I wasn’t ready to share . . . let alone with someone as vociferous as Matthew!

Besides he was notoriously fit and healthy, a former ski-instructor who rode a single-speed bike everywhere and whose physique was much commented on by the mums at the school gate. What little physical self-confidence I was regaining by dint of my steady improvement through the climbing grades would be shattered if a novice outstripped my performance at his first or second attempt.

It took barely 70 minutes. By the second route of our second session he was climbing a grade beyond me. His agility was galling. I still beat him on strength and stamina but how long was that going to last? For the first time since I’d started at Swiss I left feeling thoroughly dejected.

That night I seriously considered changing my visits to a day Matthew couldn’t manage.

4 Breaking Out of Solitary

‘A man wrapped up in himself makes a very small bundle.’

– Benjamin Franklin

The fact is, by summer 2012 I’d reached a point where I expected people to make allowances for my disability but got infuriated when I felt defined by it. I was happy for my climbing instructors to be amazed that I could tackle 5b grade routes but pissed off when Matthew climbed a grade higher and they pointed out that he had the advantage of being able to see the holds.

Fortunately the Paralympics came to town and made me re-examine my attitude.

One of the few joys of carrying a white stick is that so many people offer help. It might not always be needed but a gracious ‘thank you, I’m fine, but it’s always lovely to be asked’ is a small price to pay for feeling the kindness of strangers.

At the same time it’s a bore repeatedly explaining that ‘yes, I do have some sight’ and ‘only 3% of those registered blind in the UK see nothing at all.’ It’s hardly surprising though. In popular culture the blind are invariably sightless; presented either as stricken victims or sonically super-powered. That’s why I’d written Blind Trust; to set the record straight, to educate and entertain, by giving the reader a behind-the-lens look at what it’s like to be robbed of your vision. Building that into a crime novel seemed grimly appropriate.