9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

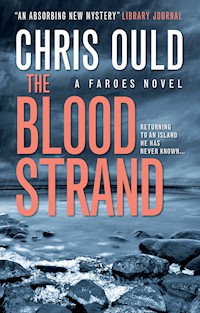

Having left the Faroes as a child, Jan Reyna is now a British police detective, and the Islands are foreign to him. But he is drawn back when his estranged father is found unconscious, a shotgun by his side and someone else's blood in his car. Then a man's body is found, a shotgun wound in his side, but signs that he was suffocated. Is his father responsible for the man's death? Jan must decide whether to stay or forsake the Faroe Islands for good.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Chris Ould

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Faroese Pronunciation

Prelude

Part One

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Part Two

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Coming Soon from Titan Books

Also by Chris Ould and Available from Titan Books

The Killing Bay (February 2017)

The Fire Pit (February 2018)

The Blood StrandPrint edition ISBN: 9781783297047E-book edition ISBN: 9781783297054

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: February 201610 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2016 Chris Ould

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Nathaniel – best boy

FAROESE PRONUNCIATION

THE FAROESE LANGUAGE IS RELATED TO OLD NORSE AND Icelandic and is spoken by fewer than eighty thousand people worldwide. Its grammar is complicated and many words are pronounced far differently to the way they appear to an English-speaker. As a general rule, ø is a “uh” sound, and the Ð or ð is usually silent, so Fríða would be pronounced “Free-a”. V is generally pronounced as w; j as a y. Hjalti is pronounced “Yalti”. In Faroese harra means “Mr” and frú is “Mrs”.

PRELUDE

BY THE TIME HERI KALSØ HAD PAID FOR HIS COFFEE, ANNIKA Mortensen was already outside, leaning on the wing of the patrol car to smoke a cigarette. She sipped her tea between drags and kept her back turned. It could not have been plainer that she did not want or expect Heri to join her.

Watching her through the window of the filling-station shop, Heri Kalsø decided he would stay inside. It was a little after 7 a.m. and in another half an hour they could head back to Tórshavn – in silence, of course – and at last put an end to the shift. Nearly eight hours was a long time to sit in the freezer.

For want of anything better to do, he made a desultory survey of the postcards in a rack by the door: the ubiquitous puffins and sheep and brightly coloured houses against mountainous backdrops. He wondered if he should buy one and write something to Annika. Would she see it as a romantic and contrite gesture? Perhaps not in her current mood. Besides, he had no idea what he would write.

If he was honest, Heri still didn’t really see what all the fuss was about. It was only one photograph, after all. Annika looked good in it, and it wasn’t like he’d been showing it round the entire station – only to Arne, although in retrospect that probably hadn’t been wise. Still, a week should be enough time to get over it, surely.

Outside, Annika Mortensen was unperturbed by the blustery, damp wind, or by the fact that she knew Heri was still feeling unfairly done by. Good. Simply blanking him whenever they passed in the station was satisfying, but being partnered together for the Sunday–Monday night shift gave far more opportunity to make her feelings clear. After this she’d let it go on for a couple more days and then maybe – maybe – she’d reconsider.

“Unit 6, receiving?”

It was Tina, over the radio. Annika answered it before Heri could jump in. “Yes, Tina, we’re here.”

“Can you go to Tjørnuvík – to the lay-by next to the radio mast on the headland? We’ve had a 112 call from a Jacob Nybo concerning an unconscious man in a car there. An ambulance is on its way but it’s coming from Leirvík, so you’re closer.”

“Is there a crime?”

“That’s unknown at the moment.”

Annika exhaled a final plume of smoke, then crushed out her cigarette. “Okay, we’ll get there as soon as possible,” she told Tina. “Leaving now.”

As she discarded her cup in the bin, Heri was coming out of the shop. “I’ll drive if you like,” he called as he approached. “Give you a break?”

Annika shook her head but said nothing.

Heri gave an exasperated sigh. “For helviti, Annika…”

But by then Annika Mortensen was already getting into the driver’s seat, leaving no room for discussion.

A little under ten minutes later they pulled in at the lay-by on the eastern headland of Tjørnuvík bay. It was high here – a forty-metre drop more or less straight down to the sea – and the hard-gusting wind rocked a rusty Toyota pickup parked on the gravel.

Annika stopped the patrol car behind the Toyota and saw that it was empty. However, when she and Heri got out of the car there was a shout from a man twenty metres away. He was standing beside the open door of a dark blue BMW 5 Series, parked part way down a slope beneath the level of the road.

What the man had shouted was lost on the stiff breeze, but his gesturing was clear enough and Annika and Heri headed towards him.

The first thing Annika noted was that although the glass from the driver’s side window lay in cubes on the gravel, the BMW showed no sign of a collision or accident. The second thing she saw was a white-haired figure slumped, apparently lifeless, over the car’s steering wheel.

“Harra Nybo? I’m Officer Mortensen, this is Officer Kalsø. Is this the casualty?”

“Ja,” Nybo nodded vigorously. “I can’t tell what’s wrong with him. He’s unconscious.”

Nybo was in his early sixties, wearing work clothes and a woollen hat. Now that police officers had arrived he moved away from the car with some relief, Annika thought.

“I’ll check him out,” Heri said. He’d brought the first-aid kit, so Annika didn’t object. She stepped aside with Jacob Nybo instead.

“Can you tell me how you found him?” she asked. “How long ago?”

“Twenty minutes, not much more,” Nybo said. “I saw the car here as I came past and I thought it was strange – you know, for this time of the morning. So I stopped to see if it was a breakdown or something, and that’s when I saw him. I thought he was asleep but when I banged on the window he still didn’t move. I tried the door but it was locked.”

“So you broke the window?”

Nybo nodded, slightly reluctant to make the admission. “I wasn’t sure if I should, but I didn’t know what else to do. I thought he might be dead.”

The unconscious man was in his seventies, Heri estimated, with white stubble and slack skin around his jowls. There was a faint carotid pulse and under a suede jacket the man’s shoulders moved almost imperceptibly with slow, shallow breaths. On his left temple there was a small graze over a discoloured lump, but nothing serious.

Heri shook the man’s shoulder again, a bit more firmly this time, but still not too hard in case there was some injury. “Hello? Can you hear me? I’m a police officer.”

Nothing.

By now Annika had approached. She examined the outside of the car for a moment, then bent down for a closer look inside.

“Has he any injuries?” she asked Heri, quickly surveying the man’s torso before her eye was caught by the polished walnut stock of a shotgun. It was propped against the passenger seat, barrels pointing down into the footwell.

“Looks like a bump on his head: nothing much,” Heri said. “Why?”

Annika Mortensen stepped back to look at the driver’s door again. “Because there’s blood here,” she said.

“Are you sure?”

Annika cast him a look then keyed her radio. “Control, from Unit 6, do we have anyone from CID free to attend at Tjørnuvík?”

* * *

After Haldarsvík the road climbed with the contours of the hillside and afforded Detective Hjalti Hentze a better view across the choppy waters in Sundini Sound. The wind was stronger up here and it broke up the clouds, letting shafts of sunlight race across the far landscape around Eiði and turn the sea a dirty turquoise where it touched.

Hentze was an unpolished man, at least in appearance. Beneath his parka he wore a thick traditional sweater, jeans and solid boots. His hair was cropped short, thinning a little on the crown, and his hands were square and stubby on the steering wheel. Hjalti Hentze had a stolidness and an unhurried temperament which suggested he was someone who would be most at home in a boat or a field, rather than dealing with the subtleties of police investigations.

But Hentze had been a police officer for the last twenty-one years, and in many ways the fact that he didn’t look like one was his greatest asset. Many people didn’t like talking to the police, but, if they had to, they often preferred speaking to someone like Hentze. Here was a man who wasn’t so very different to them, at least on the surface; here was a man who would understand their sensibilities and proceed in a calm, straightforward manner, which – for the most part – Hjalti Hentze did.

Ahead he saw the radio mast and slowed his Volvo before letting it run on to the gravel and come to a halt behind the patrol car. Inside it he saw Annika Mortensen turn her head to look and when she recognised him she raised a hand in greeting and then spoke into her radio.

Hentze forced his door open against the breeze and got out of the car. The wind whistled and moaned discordantly through the rigging and spars of the radio mast, rattling the solar panel and whipping at his coat.

The wind also swirled Annika Mortensen’s blonde hair back from her face as she left her own vehicle and came back to meet Hentze. She moved easily and with some grace, despite the bulk of her utility jacket and belt.

“Hey, Hjalti,” she said, raising her voice over the wind.

“Hey,” Hentze said. “How come you’re on your own?”

Annika made a pained expression. “I told Heri to go in the ambulance with the victim. I didn’t want him just sitting out here with a face like a cod.”

Hentze chuckled. “Things are no better between you two then?”

“No. He’s still an arsehole,” Annika told him decidedly. She tugged a stray strand of hair from her mouth.

“You’ll never change him.”

“Who said I want to?”

Hentze laughed again, then turned to look round. “So, what have we got?”

“Over here,” Annika said and gestured towards the BMW. “You know whose it is, right?” she asked.

Hentze nodded. “Signar Ravnsfjall. So Ári’s very keen that we get the full picture.”

Ári Niclasen, the inspector, was a decent guy, although not necessarily the bravest. And because old man Ravnsfjall wasn’t without significance in the islands, Niclasen had been keen to impress on Hentze the importance of getting things just right. They needed to be discreet in case the situation turned out to be entirely beyond reproach, but at the same time they should demonstrate an appropriate level of concern in case it was not.

Annika and Hentze walked across to the BMW together as Annika explained how Jacob Nybo had found the car and its occupant and had broken the window with a rock. When she’d finished she waited as Hentze assessed the shattered window glass on the gravel chippings in front of them.

“The doors were locked?” he asked. “I mean, he did try them before he smashed the window?”

“So he said.”

“Right,” Hentze nodded. Then: “What about the blood?”

“Here,” Annika said, stepping forward to indicate a pattern of smooth, reddish-brown splashes across the upper part of the door panel. Hentze moved in to look more closely, squatted down and squinted until he remembered his new reading glasses. He dug them out of his coat and perched them on his nose, then looked again.

The largest splash marks were near the top of the panel, but none of them was bigger than a one-króna coin. Lower down on the door the splashes were smaller, angled downwards towards the back of the car. Hentze was pretty sure the splashes were blood, though there was always a chance that it wasn’t human.

For a moment he considered the car as it stood, then he asked, “Who identified the casualty as Signar Ravnsfjall?”

“I found a wallet in his pocket before the paramedics took him away,” Annika said. “And I’ve checked the car registration. It’s his.”

“Did he have any injuries?”

“He has a graze on his head and also on a knee where his trousers are torn, but nothing that would have left blood splashes like that. The paramedics think he could have fallen out here, then had a stroke or maybe a heart attack once he got back in the car. He could have been here all night.”

“Will he live, do they think?”

Annika shrugged. “Sounded as if it might be touch and go.”

Hentze nodded, digesting that, then searched his pockets for latex gloves and pulled them on before moving to look inside the car.

Of course, the paramedics as well as Jacob Nybo had all been in contact with the interior and exterior of the car to varying degrees, but just the same Hentze was careful to disturb things as little as possible before he’d decided what they were dealing with.

He opened the driver’s door and looked around, noting the fact that Signar Ravnsfjall kept the interior of his car spotlessly clean. The cream-leather driver’s seat was stained by urine and faeces now, though, and the footwell was littered with cubes of broken window glass.

Changing position, Hentze reached for the ignition key and checked its position: off. He turned it to first position and the console lit up. The fuel warning sign was illuminated, too, and when he looked at the petrol gauge it was on empty.

“Was the ignition on or off when you got here?”

“On. Heri turned it off for safety, but there’s no fuel. I thought maybe the engine had ticked over all night until it ran out.”

“Or he pulled in here because he ran out of fuel,” Hentze said, although he was inclined to think Annika’s was the more likely scenario.

Extricating himself from the car, Hentze moved round to the passenger side and checked the glove box – mints, a packet of tissues – and then opened the back door to look at the shotgun which lay, broken open, on the seat. Two cartridges were still in place and when he looked more closely he saw the indentation of the firing pin in one of the brass caps but not the other.

“You said the gun was in the front when you got here?” he asked Annika.

“Yeah, in the passenger footwell. I made it safe and moved it into the back,” she told him. “I used gloves.”

“Good. We’ll bag it up for Technical. Has anyone checked the boot?”

“Not that I know of.”

Hentze moved round to the rear of the car, searched for the boot catch for a moment, then sprang the lid. Inside, the carpeted lining was as spotless as the rest of the car, the only contents a cheap, faux-leather attaché case with a plastic handle. Hentze drew it towards him, then flicked the catches open. When he lifted the lid he saw several neat bundles of thousand-krónur notes held together with paper bands. There were at least twenty of them.

By his shoulder Annika Mortensen let out a low whistle. “Bloody hell,” she said. “I knew the Ravnsfjalls were loaded, but to drive around with that much in the boot… There could be over a million there.”

Hjalti Hentze had made the same calculation. He looked for a moment longer, then closed the lid of the attaché case and snapped the catches. He thought about Ári Niclasen’s desire to play it safe.

“We’ll need some evidence bags,” he said. “And we’d better get the car taken in so it can be properly examined.”

“You think there was a crime?”

“Do you?”

Annika Mortensen assessed the car for a moment. “I don’t know. But it’s bloody strange, whatever happened.”

Hentze nodded. “I think so, too. So for the time being I think we’ll do this by the book.”

PART ONE

1

Tuesday/týsdagur

I DIDN’T SEE MUCH AS THE PLANE CAME IN TO VÁGAR AIRPORT. There was low cloud and I was seated over a wing. Once we’d landed I filed along the aisle with everyone else, down the metal steps and across to the terminal. There was no hurry.

Most of the other passengers seemed to be Faroese or Danish; dressed for business, or at least as if air travel was still a reason to turn out smartly. I hadn’t gone that far, and I wondered if it set me apart to a passing glance, or whether the layers of foreignness I’d accrued over thirty-odd years were enough to cover the base metal beneath.

When I was a teenager it had been a conscious effort to adopt all those layers, taking on a new skin, covering any differentness. But it went back further than that, went deeper.

According to Ketty – my aunt – I’d refused to speak for the first three months I was with them. I was five years old – just – and when I finally broke my silence it was only in English, refusing to acknowledge Faroese, or even Danish.

This was a product of trauma, the child psychologist had told Ketty and Peter, apparently. I don’t remember, but I’d always thought it was probably more simple than that. Even aged five I’d have known I would never go back, so why cling to the language? Why single myself out with a name no one would pronounce in the right way? Only Ketty still sounded my first name with a Y, and who in England could be bothered to put an accent on Reyná?

Jan Reyna was easier. Jan Reyna was who I was.

* * *

When I’d arrived at their house, the day before I’d flown back to the Faroes, Ketty was on the phone. She was speaking Faroese and only looked up for a moment – enough to register I was there – before looking away to write something on a pad.

In the kitchen I found Peter. We shook hands, hugged and stepped back. Always the way.

Peter Sherland was sixty-eight, still a vigorous man with a grey-black goatee. Daily Telegraph crossword, Radio 4, three swims a week and the first signs of Parkinson’s in the slight tremor of his left hand.

“I’m glad you came,” he said. “Ketty’s trying to find out more from the hospital – in Tórshavn,” he added, although it was unnecessary.

I nodded – acknowledgement, but also a way of showing I didn’t want to get into it yet. Peter took the hint.

“Coffee?” he asked.

“Yeah, thanks.”

He moved to the coffee maker. This was the way Peter dealt with situations of whatever size – taking his time, never rushing into an opinion or judgement – unlike Ketty, who was always one for instinctive direct action. She made up her mind and spoke it, rarely backing down afterwards.

I knew I’d acquired a mixture of these traits, but it was Peter’s way I’d always admired and aspired to, even when I heard myself speaking as Ketty would do. Maybe seeking to be like Peter was just a way of trying to show my appreciation for what he’d done: taking me in, the adoption, and then putting up with all the shit that came later. I still didn’t know what it had cost him to suddenly have that troubled boy as part of his life. I’d never been able to ask, either. Instead I just tried to be measured.

“Did you have any trouble getting away?” Peter asked. He ferried two espressos to the kitchen table – one at a time because of his tremor.

“No, they can manage,” I told him, momentarily regretting the lie.

He nodded, sat down. “Anything you can say?” Ever the solicitor.

I made a half shrug. “Not much. They made an arrest but there’s not enough to charge yet.”

He sipped his coffee.

“So listen—” he began, changing tone. But before he could finish, Ketty came into the kitchen.

I went over and kissed her on the cheek. She was still a striking woman – high cheekbones, grey-blonde hair cut on an angle, blue eyes given to smiling, although they were serious now. She kissed me back, then stepped away.

“You have to go, Jan,” she said without any preamble.

I wondered if I heard more of an accent now because she’d just been speaking her own language on the phone.

“What did they say?”

I moved back to my seat: a way to distance myself from the response.

“That he’s seriously ill. It was a large stroke.”

“Will he die?”

“They won’t say that.” She shook her head. “But when I said I was ringing for his son they said that they think his relatives should come.”

I wondered if all hospitals adopted the same standard euphemisms.

“I can’t do anything,” I said.

“That’s not the point.” For a second her tone was annoyed, as if I was being wilfully stupid. “Not to go now…”

She was still standing and I knew she wouldn’t sit down. That was what she was like. She’d stand firm until she got what she wanted or I left. There wouldn’t be any compromise.

“I can’t just pick up and leave,” I said. Another lie.

“They won’t let you go even if your father might die?” Her turn to be wilfully obtuse.

“Ketty—” Then I shook my head, negating it. “You can’t bully me into going,” I said. “Why the hell would I? I wouldn’t even be thinking about it if he’d died.”

That was true. Why go back, just to stand at a graveside?

But Signar Ravnsfjall wasn’t dead. He was in limbo; at some halfway point on the scale, like the questions that had always been there, not yet asked or answered. The “yet” implied there was still time for it, but I doubted that. So why go back just to stand at a bedside?

“If Signar was dead it would be too late,” Ketty said. “It would be different. Now you have a choice.”

“I can live with that.”

“Good. You’ll have to.” She said it with a decided nod: flat.

“Ketty…” Peter’s tone was mildly reproachful.

But Ketty wouldn’t shift. “You’ll never know unless you see him.”

“I don’t need to know.”

“Yes, you do. You don’t see it – maybe you don’t want to see it – but I do.”

I drew a slow breath. In an interview room I usually know when the suspect across the table has reached the turning point. There will be a pause – the moment of balance – and if their next words are anything other than “no comment” you know that the truth will come out. It might still be slow or grudging, but the path has been chosen.

My own “no comment” would be to turn away now, pick up and go.

“I tried before,” I said.

She shook her head. “You were seventeen,” she said. “Try again.”

* * *

Once the baggage carousel started to move my holdall appeared relatively quickly and I towed it past non-existent passport control and customs checks, then through the entrance hall to emerge from the low terminal building. Outside, people were already dispersing to cars and minibuses, but I paused under the overhanging shelter, wanting to give myself a moment of adjustment before moving on.

There was a sense of altitude here, and between breaks in the low, rolling grey cloud the sun glistened off the car park’s wet tarmac. The air was cool, cold even, after the unseasonal September heat I’d been used to in England. The wind shepherded the clouds quickly across the bowl of sky between the undulating, rounded peaks of the surrounding mountains and fells. The landscape was treeless, brown-green. In places it was traced out by black strata of rock, as if the long-buried bones of the hills were gradually being exposed by erosion. I knew the feeling.

The second taxi I approached – a minivan – was free and I sat in the back behind the driver as a signal that I didn’t want to talk. Instead I checked my phone as the van pulled out of the airport, then settled to watch the passing terrain: sculpted and weathered, often crossed by water in streams and cascades.

The smooth, sweeping road gave a sense of plunging through the landscape as if on a theme-park ride and I got the same feeling of make-believe when I looked at the villages and settlements as they passed, laid out in the valleys and inlets. The buildings were painted in primary colours, saturated by the patchy sunlight, as simple and angular as illustrations from a child’s storybook. There was an underlying otherness to it all, it felt to me then – a vague foreignness that was hard to define, but a sense of uneasy familiarity, too.

Where from?

Was it a real recollection, or a memory of a childhood picture book? Either would have to have come from the time before Lýdia took me away from the islands, but now, as ever, I couldn’t penetrate the void of childhood – not of living here, not of the first years in England. It was too far away and in the end I left it alone and simply watched the landscape going past, with no fixed point of reference and no sense of home. Because it wasn’t.

2

BY THE TIME THE TAXI REACHED TÓRSHAVN THE BRIGHT PATCHES of sunshine had given way to a grey drizzle. I persuaded the driver to wait while I dropped off my bags at the Hotel Streym, and then to take me on to the hospital. When we pulled up outside the block-like building I paid the driver off with crisp Danish notes from a bureau de change envelope and went in through sliding glass doors to look for the main desk.

The visiting hour had just started, I was told, and after getting directions, I took the lift to the third floor, navigating the Faroese signs as best I could until I reached a nurses’ station and asked where I could find Signar Ravnsfjall.

The nurse was in her late twenties and took a moment to think herself into English. “I’m sorry, the visiting hour is for the family only,” she said.

“I’m his son,” I told her. “From England.”

I knew that the last bit was clumsy: an attempt to distance myself from the claim of kinship and hold it at arm’s length for a little while longer. “Ah. Okay,” the nurse said. “At the moment the family are with him. Perhaps I can tell them you’re here. You can come to the visiting room.”

I followed her round a corner on to a corridor where she showed me into a glass-fronted room with firm-looking sofas and a view of the harbour. Leaving me there she went off, further along the corridor, but after a moment I returned to the doorway and waited. I didn’t want to sit.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!