6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

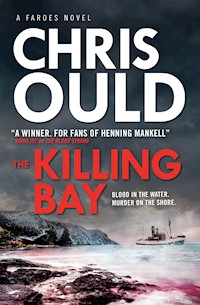

When a group of activists arrive on the Faroe Islands to stop the traditional whale hunts, tensions between islanders and protestors run high. And when a woman is found murdered, circumstances seem designed to increase animosity. To English DI Jan Reyna and local detective Hjalti Hentze, it becomes increasingly clear that evidence is being hidden from them, and neither knows who to trust, or how far some people might go to defend their beliefs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Chris Ould

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Faroese Pronunciation

Prelude

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Chris Ould and available from Titan Books

The Blood Strand

The Fire Pit (February 2018)

The Killing BayPrint edition ISBN: 9781783297061E-book edition ISBN: 9781783297078

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: February 201710 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2017 Chris Ould

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For me mam,At last, and with love

FAROESE PRONUNCIATION

THE FAROESE LANGUAGE IS RELATED TO OLD NORSE AND Icelandic and is spoken by fewer than eighty thousand people worldwide. Its grammar is complicated and many words are pronounced far differently to the way they appear to an English-speaker. As a general rule ø is a “uh” sound; v is pronounced as w; j as a y, and the Ð or ð is usually silent, so Fríða would be pronounced Free-a. Hjalti is pronounced “Yalti”.

The word grind (pronounced “grinned”) is Faroese for a school of pilot whales, but is also used generically to refer to the whale drive and associated activities.

PRELUDE

HE WORKED ON HIS KNEES NOW, AS IF PRAYING. DARKNESS and rain; darkness and pain – from his back, from his fingers, from all over. Sweating and hot, working blind: as good as blind. The yellow light from the torch was so feeble it lit only the grass a hand’s length in front of it.

The rocks were heavy: rough basalt, flecked with green. Abrading his fingers and nails as he scrabbled them free then heaved them aside. It was harder now that he had reached the lowermost stones. Over years – decades – they had grown into the earth; or the earth had grown into them, unwilling to give them up. He should have brought tools. But he had only a torch and the vodka.

Coming here in darkness had been instinctive. Something held silent and hidden this long couldn’t be exposed in the light. It still demanded the ritual of secrecy, even in its uncovering. He needed the darkness and the vodka to cover his fear.

Another stone broke free. He rocked back with the shock of its release and let it fall to the side and roll down the slope. He panted, half sobbing. How much more could there be? How much more could he do? He was weak, he knew that. Weak-willed and weak of body – more now than ever. It was only his fear that kept him going. Fear was all he had left.

For a minute, then longer, he didn’t have the strength to raise his chin from his chest. He felt sick and hollow: a shell, eaten up from the inside. Eaten up, eaten away.

How much more?

He reached for the torch; brought it up, shook it, and was rewarded, he thought, by a faintly brighter light.

Thrusting it forward he played the glow over the rocks, into a hollow, tried to make sense of the shadows it made.

And then he recoiled with an exclamation of shock. Fumbled the torch, dropped it; felt his heart racing. Smooth roundness, mottled with dirt. Not rock. Bone.

She was there.

* * *

At the grave there was stillness and nothing to see within the circle of family black. The pastor’s voice fluctuated on the wind, but he was twenty yards away and even if the sound had carried clearly all I’d have understood was the tone.

On the far side of Skálafjørður patches of sunlight came and went, daubing and shifting over the distant hillsides. My eye was drawn by the movement, following the light as it picked out the scattered dots of houses in a place I couldn’t name; then drawn again by the distant movement of a car on the shoreline road, glinting. It was that kind of day: one of the bright ones when the rain has passed and you can have a fresh start.

Before I’d left England I’d said that I wouldn’t come here to stand by a graveside. It hadn’t been my intention, but there again I was pretty sure that dying hadn’t been Signar Ravnsfjall’s intention either – not if he’d been aware enough to think about it after his penultimate stroke.

Even if intention and result are two different things, I’d stayed true to my word: I was not by the graveside. That was for family. He’d been my father in name only – not even that – and to remain at this distance seemed about right.

And then the breeze shifted and it was all done. Signar Ravnsfjall was in the ground and beside the grave the mourners were released from their stillness. I cast a last look and then moved away.

* * *

The church at Glyvrar stood above a slope that ran down to the waters of the fjord, choppy and restless. The building wasn’t one of the traditional Faroese churches, with tarred clapboard walls and grass on the roof. Instead it had the look of architectural thinking – solid white walls, with a square tower and steep-angled roofs nested together. The car park beside it put me in mind of an out-of-town shopping centre. It was full now. The great and the good had turned out in force to send Signar Ravnsfjall on his way.

My half-brother Magnus Ravnsfjall found me about ten minutes later as I stood by the car. It must have taken some determination to do that, given the number of people still clustered round the church. They were in no hurry to leave until news and views had been passed and chewed over: it’s the Faroese way. No hurry at all.

I watched Magnus exchange a few words with a cluster of smartly dressed men near the gates of the churchyard, but he clearly didn’t want to linger. After nods and a few words he moved on.

I’d bummed a cigarette from one of the same men a few minutes earlier, but now I trod it out and went forward to meet my half-brother. And for a moment it struck me as odd that he could still have such a resemblance to the man they’d just buried, as if Signar’s death should have lessened the physical similarity between father and son. It hadn’t though, and I guessed that Magnus had probably inherited the mantle of Signar’s business concerns, to go with his genes.

“Will you come with us now to the house?” Magnus asked when he stopped in front of me. “It will be only family and close friends. My mother doesn’t want more, but she would like to meet you.”

I shook my head. “Nei, men takk fyri. I don’t think it’s the best day for introductions, do you? Besides, if Kristian’s there…”

Whatever Sofia Ravnsfjall’s reasons for wanting to meet me, I couldn’t see Kristian being thrilled by my presence. He was my half-brother, too, but I knew him much better and because of that I doubted he’d want me around. His wounds would still be too raw.

Magnus understood what I meant, but for a moment he seemed undecided, as if still under some imperative. In the end, though, he nodded. “Perhaps in a day or two, then. You’re not leaving yet?”

“No, not yet.”

“Okay.” It seemed to satisfy him. “There are also some details from our father’s testament – the will – that we should discuss.”

I couldn’t guess what sort of details those could be. “Sure, if you need to,” I said. “Give me a call.”

“Thank you.” He said it as if I’d granted a favour. Then, for a moment, he was distracted by the view across the sound.

“It’s a good place to be, isn’t it?” he said.

Better if you were above ground, instead of below it. But I didn’t say that. He’d lost his father and I knew they’d been close.

“Yeah, a good spot,” I said.

He drew himself back to the moment. “Okay then,” he said. “I will call you. Thank you for coming.”

We shook hands and he moved back towards the church passing Fríða, my cousin and, for the last week, also the provider of a roof over my head. She knew where I’d be and didn’t have to search. Today was the first time I’d seen her wearing a skirt and heels – all formal black – and they suited her. With her blonde hair up in some kind of knot she looked effortlessly stylish and when she arrived at my side she put her arm lightly through mine.

“Will you come to the house?” she asked. “My father will take us.”

I liked Jens Sólsker, her father, but I shook my head. “Magnus just asked, but I don’t think so.”

She assessed that for a moment, then said, “Okay, I understand. You had better take the car then. My father will give me a lift later.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yeh, of course.” Ever the pragmatist. She held out the keys and looked at me as if assessing the damage, or lack of it. “You’ll be okay?”

I nodded. “I’ll go for a walk,” I said.

“Okay,” she said, then she gave me a small hug before extracting her arm. “Safe home, then.”

“You, too.”

* * *

A little before nine and still a couple of hours from the end of the late shift, Officer Annika Mortensen passed the multi-coloured lights in the Norðoyatunnilin – the grotto, as she always thought of it. Red, green and blue floodlights shone up the rock walls and across the roof of the road tunnel to mark the deepest point under the sea, halfway between Eysturoy and Borðoy.

Annika was heading for Klaksvík to meet up with Heri Kalsø for a coffee and hotdog at the Magn petrol station: hardly the most glamorous of locations, but convenient enough. A bit like their relationship, she thought, and then immediately chastised herself. It was an unkind assessment, especially because she knew it wasn’t one Heri would share.

There was little traffic in the tunnel and Annika kept her speed at a steady eighty up the incline, half listening to an REM song on the radio. Then the tunnel ended and she emerged into the night. Up ahead she saw three or four cars on the shoulder of the opposite lane, just past the first curve of the road. A couple of people were looking into a car that was pressed up against the embankment just beyond the junction with Mækjuvegur.

Annika assessed the situation, then slowed. She let an oncoming car go past, then switched on the blue roof bar lights and crossed the carriageway, pulling up in front of the first car; a VW Polo with its nearside front tyre down in the mud. Beside it a man in a Föroyar Bjór bomber jacket had opened the driver’s door and was leaning inside; an older man was peering over his shoulder.

“Hey,” Annika said as she approached. “What’s happened?”

“Don’t know,” the older man said. “I was following him about fifty metres behind and he just drove off the road.”

“How fast was he going?”

“Not very. About forty maybe. I had to slow down.”

The man in the Föroyar Bjór jacket stood away from the door now to let Annika see. She moved forward and bent down to the driver, but the smell of alcohol and unwashed body told her as much as his lolling head. He was well into his sixties, greying hair down over his collar and a face grizzled with a grey beard where it wasn’t streaked with dirt.

“Hey, hey, can you hear me?” she asked, putting a hand on the shoulder of the man’s greasy tweed jacket. “Are you okay?”

No response. His clothes were muddy and wet, especially the knees of his trousers, Annika noticed, and there was a bottle of vodka on the passenger seat, uncapped and empty.

Annika considered, then pinched the man’s earlobe, hard, between her thumb and index fingernail.

It did the trick. The old man roused with a snort and a swatting motion from his hands, as if trying to fend off a fly.

“Wha— Where’s this? I don… Where?”

“Talk to me, please.” Annika’s tone was insistent. “Are you hurt?”

For a moment the man tried to focus. “She… she wa’ dead… I need to… Not me to…”

He trailed off into incomprehensible mumbling and his head lolled again. Annika frowned. As drunk as a halibut, as her gran used to say. Not an ambulance job though. She straightened up from the car.

“He’s pissed again, right?” the man in the Föroyar Bjór jacket said.

“Again? Do you know him?”

“Sure, that’s old Boas,” the man said. “Boas Justesen. He lives near my sister in Fuglafjørður. He took to the bottle when he lost his job in the 1980s – hasn’t put it down since.”

The name seemed vaguely familiar to Annika, which wasn’t saying a lot: it was harder not to know people around here. Something about his wife dying? Maybe. It didn’t matter.

“Will you give me a hand to move him?” she asked the man. “Just as far as my car.”

By the time Annika had secured Boas Justesen’s car, turning off the lights and locking the doors, the man himself was slumped across the back seat of her patrol car snoring. There was also a powerful smell of urine. Annika opened her window and switched on the fan.

There was no point driving Justesen to Tórshavn to be charged: he was too drunk. Instead Annika called the station and arranged to take him directly to the holding cells in Klaksvík; something she would have had to do anyway now that Tórshavn’s own cells had been closed. Even arrestees from the capital ended up being driven the seventy-five kilometres to Klaksvík for holding. It made no sense and wasted everyone’s time, but there it was. At least this time she was only five minutes away.

* * *

When Annika drew up in the parking lot outside the station Heri Kalsø was waiting. He’d heard her call to control and was pleased to have the opportunity to come and lend a hand, manhandling Boas Justesen out of the car and as far as the cells.

Ever since the incident at Kollafjørður when Sámal Mohr had been decapitated, Annika seemed to have put aside the fact that she had ever been mad with Heri; at least, she hadn’t mentioned it again, and it had been more than a week since the incident. Heri wasn’t sure if this was because of the way he’d reacted at the accident scene – by taking over and getting Annika away – or whether Annika’s forgiveness would have come anyway. He wasn’t foolish enough to ask, though. The burnt child fears the fire, and he’d learned his lesson. No, things were back to normal, and it was better to leave it at that. He’d even started to think again about asking Annika to move in with him. It fell short of a proposal of marriage, but that might be too much, he’d decided. The first thing was to gauge her reaction. They’d been together for over a year. Time for a change of gear, surely.

* * *

Once Boas Justesen had been booked and deposited in a cell Annika decided to put off cleaning the back of her car until they’d had coffee and something to eat. They took Heri’s car for the short drive to the Magn station and Annika sat in the passenger seat.

“I’ve applied to join CID,” she said as Heri negotiated the parking lot to the road. The words just came out. She had no why. Perhaps because it was dark.

“Yeh? That’s great,” Heri said, glancing at her. “You should. You’ll do well at it, especially if Hjalti takes you under his wing. Which he will.”

Annika shook her head. “I don’t mean here: I’ve applied to Copenhagen.”

“Copenhagen? Why?”

“Because they have a wider variety of cases. That’s what I want, so I can see which area really interests me. I’ve been thinking about the homicide squad.”

“You just worked on a homicide case: Tummas Gramm.”

“Yeh, I know,” Annika acknowledged. “But how long till the next one comes along here?” She sensed Heri stiffen in his seat but he didn’t reply, instead turning the car on to Biskupsstøð gøta.

“I’m not saying I want to stay there for good,” Annika went on, filling the silence. “I think two or three years to get experience, then it might be good to come back.”

“Sure, yeh,” Heri said. “That makes sense.”

“So you’d be okay with it?”

“Sure, of course. It’s not like it’s so far away, is it?” Heri flicked the indicator and turned in at the petrol station. “An hour and a half on the plane. That’s only the same as driving out to Viðareiði.”

“Yeh, well that’s true,” Annika said. “When you put it like that.”

1

Friday/fríggjadagur

“JAN?”

It came after the knock on the back door. Fríða’s voice.

“Hey. Koma í,” I called.

A moment or two later she came into the sitting room. I’d known she hadn’t gone to the clinic because her car was still parked outside, but I’d assumed she was working from home so I’d left her alone instead of crossing the six feet between the guest house where I was staying and the main house. She was wearing jeans and trainers beneath a chunky-knit sweater, her reading glasses pushed back into her hair.

“Do you feel like an expedition?” she asked. I saw her spot the large, buff envelope on the table and the empty coffee mug near it.

“To do what?” I asked, partly to redirect her attention.

“A trip to Sandoy. Finn – my brother – has sent me a text from his boat. They have found a pod of whales so there will be a grind at Sandur, unless they escape.” She checked her watch. “We’ll have to leave in a few minutes, but if we’re lucky I think we can catch the next ferry from Gamlarætt and be at Sandur by the time they arrive – but only if you want to,” she added. “If you want to see it.”

“Are you going anyway, or would it just be for my benefit?” I asked. I had a suspicion that Fríða thought I needed more exposure to my cultural roots. At various times she’d brought me books she thought I should look at – collections of old photographs of the Faroes and novels by Heinesen, Brú and others. I wasn’t sure I agreed with her diagnosis, but I appreciated the thought.

“No, I’ll go anyway,” Fríða said. “I haven’t seen Finn for a while and it’s a nice day.”

A nice day to kill whales.

“Okay, sure,” I said. “Do I need to bring anything? Harpoon? A big knife?”

She gave me a look, slightly beady, but she was getting used to me by now. “No, I don’t think you need anything like that,” she said. “You don’t want any more injuries, I think.”

She could be very sardonic, which I liked.

When she’d gone I went to find boots and waterproofs. Essentials, even for a nice day on the Faroes. At least I was that much in touch with life here.

* * *

So where was I?

Mending/mended. Suspended. Putting things off: decisions; movement; leaving; asking. I supposed I was waiting for something: to take a hint. I can take a hint. But there was none, and I had no imperative until one came along.

Fríða had still given no sign of wanting to kick me out of the guest house and a few days ago when I’d told her I thought it might be time I went back to a hotel she dismissed the idea as if I’d suggested something illogical. “Why? There’s no need. It would be a waste of money.”

I didn’t want to impose on her hospitality or outstay my welcome – I was still English enough for that – but if I read it right, she viewed my presence as a pragmatic solution to my situation: first injured, then – after the news of Signar’s death – awaiting his funeral. I also knew her well enough not to argue when she’d made up her mind.

So I stayed.

I’d also emailed Kirkland, my superintendent back in England, and told him I was unavailable to be interviewed by the Directorate of Professional Standards on the dates he’d requested. I used the word request deliberately because it hadn’t been one. There had been a family bereavement, I told him; on top of the fact I was recovering from injuries sustained while assisting the Faroese police. I even offered to provide medical notes and testimonials if he required them. Not necessary as it turned out. I hadn’t thought so. He knew what he could do.

And I walked.

Not to outdistance or shake off the black dog, but because I wanted to. Because, by and large, I hadn’t walked for the sake of the walk for a long time and if I tired myself out I hoped it might bring my sleep back to normal.

Ever since the concussion and painkillers had scrambled a couple of my days I’d been waking in the small hours, vaguely conscious that in my dreams I’d been inhabiting a place I didn’t like. It was a sensation I remembered, like déjà vu, from almost a lifetime away: a primal thing, almost childlike in its simplicity. Maybe not surprising because I had been a child when I’d last felt it: waking up and not knowing where I’d been.

So I walked, and after the first day when I’d underestimated the terrain, I remembered the addictive muscle-aching satisfaction of accomplishment it gave. This was something I could do, and while I was doing it there was nothing else I could do at the same time: just be preoccupied by the next step and the one after that.

So, that’s where I was: abstracted from reality, I guess. As much in limbo as Signar Ravnsfjall had been when I’d seen him that one time in his hospital bed, between his first stroke and his last. Unresolved. Unanswered. Unfinished.

2

BEHIND THE BOAT THE WATER WAS CHOPPY AND DISTURBED BY the wakes of the pursuing craft; half a dozen, strung out in a loose, ragged line, engines throbbing. Ahead, though, the water was calm, almost unbroken even by the smoothly arcing dorsal fins as the pilot whale pod sliced the water with apparently effortless ease.

Did they even realise they were being herded? At the wheel of the Kári Edith Finn Sólsker had wondered about this before. They were supposed to be smart, these whales. So why didn’t they just turn, dive beneath the boats and head for open water instead of the mouth of the bay? But they just didn’t. That was the way of it.

In the bow of the boat Høgni Joensen stood by the rail, leaning forward slightly into the light breeze. He was a short, square man with coarse hair under a woollen hat and a stubbled, round face which bore a broad smile. He was caught up in the sight of the whales and the thrilling uncertainty about whether or not things would go to plan. Everything else was forgotten until the regular beat of the engine faltered for a moment, then picked up again.

Even though the interruption was brief, Høgni cast a glance back at the engine hatch, then towards Finn Sólsker in the wheelhouse. Høgni had cleaned and reinstalled the fuel pump a couple of days ago, so if it started to play up again now it would be his fault. And to choose this moment, that would just make it worse. Høgni always wanted Finn to know that he could rely on him and trust him to do a good job. But as often as not the world conspired to undermine him in front of his friend and employer.

By now the Kári Edith and the other boats were drawing level with the point at Boðatangi and the vessels on the outermost, easterly end of the line began to speed up a little, bringing them round to make a large, shallow semi-circle. The intention was to force the whale pod to bear around to the left and head for the broad beach at Sandur.

Off the port side Høgni saw a flotilla of smaller boats, waiting close to the shore for the pod to pass before coming in to join the drive. It was still too far away to see how many people were on the beach, but Høgni could guess that there would be a fair few. In the two hours since the whales had first been spotted there had been plenty of time to put out the news.

Then the engine faltered again – slightly longer this time – before picking up once more. Høgni debated for a moment, but then decided it would be better to face Finn now, rather than wait until – if – the pump packed up for good. He left his place in the bow and went back to the wheelhouse.

Finn was on the radio, talking to Birgir Kallsberg, the whaling foreman, who was on the Ebba. He didn’t look away from the window when Høgni opened the wheelhouse so Høgni just stood there and waited, then dug out his tobacco tin and started to roll up, so it didn’t look like he was standing there like a moron.

“Okay,” Finn said into the radio’s handset. “Once the others are in line I’ll drop back and head in to the harbour.”

“Understood,” Birgir Kallsberg’s voice came back through the speaker. “Don’t worry, you’ll still get the finder’s whale.”

“Yeh, yeh, I trust you,” Finn said with a laugh.

He hung up the handset as the boat’s engine spluttered and misfired again. This time there was a definite drop in speed before it picked up.

“I reckon it’s that fuel pump again,” Høgni said. He realised it was a stupid thing to say as soon as it was out of his mouth.

Finn nodded. “I hope that’s all it is.”

“Yeh, yeh, it is, I’m sure of it,” Høgni said, trying to be reassuring. “We should probably have got a new one instead of trying to fix it again.”

“Yeh, maybe.” Finn allowed. “Too late now, though. At least we’re not fifty kilometres out: that’s one thing.”

Seeming to take this as an indication that Finn wasn’t going to blame him for the fault, Høgni stepped into the wheelhouse. “I’ll have a look at it as soon as we’re back at the quay,” he said. “I’m not bothered about the kill.”

The affected nonchalance wasn’t lost on Finn. Høgni loved the grindarakstur. He took the roll-up from Høgni’s stubby fingers and put it to his lips. “Don’t worry, I’ll do it later,” he said. “No need to miss out.”

Høgni passed him his lighter. “Do you think those Alliance people will turn up and try to spoil things?”

Finn chuckled. Høgni was like a little boy, everything seen in black and white: good or spoiled; liked or disliked; friend or enemy. Except that Høgni had no enemies: he was too good-natured for that.

“What?” Høgni said, reacting to Finn’s laugh.

“Nothing,” Finn told him, waving him out of the wheelhouse. “Go on, go back and watch. The protesters are probably all still in bed.”

* * *

At the eastern end of the broadly curved bay, Erla Sivertsen panned her camera along the line of people standing on the grass-covered sand dunes above the beach. More were arriving – men, women and children – coming from the road and a line of parked cars. Some of the men carried ropes and hooks, striding purposefully until they reached the edge of the grey sand, then halting to look and assess. No one went further. That was the way of it. You waited until the whales came to the beach.

At each end of the bay there were groups of AWCA volunteers, easy to pick out through the viewfinder because of the light blue sweatshirt they all wore. AWCA, pronounced as “Orca” by its members, was the Atlantic Wildlife Conservation Alliance. They had been on the islands for nearly two months, but this was the first time they had been scrambled, ready to take action, and it seemed that only a dozen or so had made it here in time. Now, like everyone else, they stood with their attention trained on the sea, watching the line of disparate boats ploughing closer and straining for sight of the whales.

Erla shifted the camera again, adjusting the focus on the telephoto lens. There were nearly two dozen police officers stationed at intervals along the line of the sand dunes, all dressed in tactical gear. Some had been brought in by a naval helicopter – clearly a show of strength by the authorities – and Erla knew that when her footage was edited the dark uniforms and bulky equipment of the police would look truly ominous in contrast to the unarmed AWCA protesters.

Having captured the scene down the length of the beach, Erla stopped filming for a moment and checked the progress of the boats out at sea. She’d witnessed four other grinds in her life – the first when she’d been six or seven years old – and knowing the way things would go now, she’d already planned the footage she wanted to get. Video was not her favourite medium, but she knew it would have the most impact when showing the actual drive. Then she’d use stills for the aftermath of the kill.

The whales were still more than three hundred metres from shore but now there was a growing desperation in their movements. They had sped up and broke the surface of the water more often. Their slick, arching bodies were more tightly grouped, as if they sensed that they were running out of room to manoeuvre. And still the boats came on behind them, grouping them tighter, pushing them in.

Finally the larger boats slowed and stopped to let the smaller craft take over and Erla knew it was time. She moved the camera and refocused on the Alliance protesters at the nearest end of the beach, waiting.

And then it started. At a signal the protesters moved into action, each taking a length of scaffolding pipe from the ground and then running quickly down towards the water. No one pursued them, but there were shouts of protest and gestures of resentment from the locals on the dunes.

The protesters paid no heed. They waded straight into the water, using their metal poles like walking sticks to test the bottom, moving out further through the low, rolling swell until they were thigh deep, spacing themselves out at intervals. And then, in a ragged line, they produced hammers and crow bars from pockets and waistbands and started to bang their submerged scaffolding poles as hard as they could, adding to the noise with shouts and whistles.

It was a tactic no one had anticipated and for a moment the onlookers weren’t sure how to respond. The police shifted uncertainly, but then they seemed to receive an order over their radios and left their positions to jog quickly across the sand and into the water. They were followed by several men from the crowd and when the protesters saw them wading into the shallows they redoubled their noise-making and moved further out into the water.

Because the water hampered everyone’s movements equally it produced the strange effect of a slow-motion game of tag in which no one could outdistance anyone else. Whenever the police made headway towards them, the protesters waded deeper or moved left or right, all the while keeping up their hammering and whistling, which became ever more urgent as the whales got closer to shore.

Erla kept the camera trained on this cat-and-mouse game for a few seconds more, then zoomed out and panned round to the open sea. The whales were concentrated together now and behind them the bullying boats had increased their speed. It almost seemed that the whales and boats were racing each other to be first to the land, but then – a few metres from shore – the whales hesitated, as if realising their mistake. A few made to turn back, but the imperative of the boats prevented it, and then, as the creatures finally reached the shallows, the people on the dunes swarmed forward. They ran across the sand and plunged into the water amidst the thrashing of fins and black bodies and Erla held the shot, zooming in slowly on the churned waters and the first men to seize their prey.

Through the lens Erla spotted an AWCA sweatshirt, adjusted the focus and managed to zoom in close on an American woman she recognised, just as she was finally corralled between two burly cops. They were all up to their chests in the water and seeing the whales already thrashing in the shallows, the woman appeared to realise she’d failed. When the police officers took her by the arms she just stood there, and as Erla zoomed in closer she was pleased to capture the look of abject misery on the woman’s face. Even at this distance you could see that she was crying with grief. It was a good picture.

Finally lifting her eye from the viewfinder, Erla glanced around. There were a few spectators nearby but everyone’s attention was focused on the whales and no one took any notice of her as she quickly unclipped the camera from its monopod and started down from her vantage point. Her AWCA sweatshirt was well covered by her red waterproof jacket and there was nothing to tell her apart from the other Faroe islanders.

3

WE’D MISSED MOST OF THE KILLING, BUT I WAS AMBIVALENT about that. Besides, there was plenty to show what we’d missed, and it was bloody. A deep crimson stain spread the width of the beach, out through the water and a good thirty yards away from the sand. It looked like someone had emptied a tanker of chemical dye into the sea.

By the time I reached the far end of the beach I couldn’t see Fríða. She’d been waylaid by an angular, insistent woman in the throng of spectators, someone she obviously knew, and I’d wandered on without her, between the onlookers at the wave line, taking the scene in until I was at the end of the beach. I chose a relatively dry spot on the sand and sat on my coat, braving the breeze in only a fleece. It was a decent day and as good a place as any to wait and observe.

There was something of a holiday mood on the beach, but now that most of the excitement was over, the people standing along the waterline had turned their attention to neighbours and fellow onlookers, gossiping and comparing impressions. While the adults talked, local kids came and went between them, daring each other to splash in the red waves, or standing intently as they watched the men still at work in the shallows.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!