3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Muhammad Humza

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

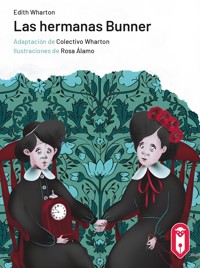

The Bunner Sisters (1892) takes place in a shabby neighborhood in New York City. The two Bunner sisters, Ann Eliza the elder, and Evelina the younger, keep a small shop selling artificial flowers and small handsewn articles to Stuyvesant Square's 'female population'. Ann Eliza gives Evelina a clock for her birthday. The clock leads the sisters to become involved with Herbert Ramy, owner of 'the queerest little store you ever laid eyes on'. Soon Ramy is a regular guest of the Bunner sisters, who realize that their 'treadmill routine', once so comfortable, is now 'intolerably monotonous'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Edith Wharton Biography

Early Years

Edith Wharton, an American author and Pulitzer Prize winner, is known for her ironic and polished prose about the aristocratic New York society into which she was born. Her protagonists are most often tragic heroes or heroines portrayed as intelligent and emotional people who want more out of life. Wharton's protagonists challenge social taboos, but are unable to overcome the barriers of social convention. Wharton's personal experiences, opinions, and passions influenced her writing.

Edith Wharton was born Edith Newbold Jones on January 24, 1862, in New York City to George Frederic Jones and Lucretia Stevens Rhinelander Jones. Her family on both sides was established, old-money New York business aristocracy. Her ancestry was of the best English and Dutch strains. Edith had two older brothers: Frederic Rhinelander Jones (Freddie), sixteen years older than her, and Henry Edward Jones (Harry), eleven years older. Because her brothers went to boarding school, and so were often away from home, Edith was essentially raised as an only child in a brownstone mansion on West Twenty-third Street in New York City. The Jones family frequently took trips to the country and to Europe. From the beginning of her life, Edith was immersed in a society noted for its manners, taste, snobbishness, and long list of social do's and don'ts.

Education and Early Work

Edith did not attend school; according to the custom of the day for well-to-do young women, she was taught at home by her governess and tutors. She became proficient in French, German, and Italian. The books in her father's large library became her passion. She read English and French literature by Jonathan Swift, Daniel Defoe, William Shakespeare, John Milton, Jean Racine, Jean La Fontaine, and Victor Hugo. She read all of Johann Goethe's plays and poems and the poetry of John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley. Edith was fascinated with stories and began composing them herself when she was a child; she called the process "making-up." Her parents did not encourage her writing; however, after Henry Wadsworth Longfellow recommended that several of Edith's poems be published in the Atlantic Monthly magazine, her parents recognized her talent and had a volume of her poems (entitled Verses) privately published. A year later, when Edith was only sixteen years old, she completed a 30,000 word novella entitled Fast and Loose, a story about manners that mocks high society.

At the age of seventeen, Edith was immersed in her books. She spent her time studying, reading, and writing and was indifferent to people her own age. Worried about Edith, her parents decided that she should make her debut in society. Despite her natural shyness, she was a social success. In August 1882, at the age of nineteen, Edith became engaged to Harry Stevens, a prominent figure in New York society. By October of the same year, the engagement was broken as a result of meddling by the mothers of the engaged couple.

Married Life

On April 29, 1885, Edith married Edward R. "Teddy" Wharton, a friend of her brother. Teddy, who was thirteen years older than Edith, was from a socially acceptable Boston family. After their wedding, the Whartons settled in New York City and soon purchased a home in Newport, Rhode Island. Teddy supported them both on his inherited income, which made it possible for the couple to live in New York and Newport, and to travel to Europe frequently. In 1902, they moved into their mansion, "The Mount," in Lenox, Massachusetts. Having collaborated with architect Ogden Codman on a book entitled The Decoration of Houses (1897), Edith put her knowledge to use and provided input regarding the design of the mansion as well as the interior decoration.

Though they were intellectually and sexually incompatible, the Whartons lived a companionable and expensive life, traveling back and forth between Europe and the United States. During the first years of Edith's marriage to Teddy, he was a companion to her and secured her position in the aristocratic society that she denounced, yet valued, throughout her life. Soon, however, events began to cloud their marriage. As Edith's writing abilities increased, so did her reputation. During the 1890's Edith wrote short stories for Scribner's Magazine, published The Valley of Decision (1902), a historical novel, and The House of Mirth (1905). She spent a considerable amount of time with would-be and genuine literary personalities and Teddy found himself in the background of Edith's life. His health and mental stability became progressively worse and required increasingly prolonged therapeutic trips to Europe. In 1907, the Whartons settled in France in the fashionable Rue de Varenne. While Edith's marital relationship (which had never been an intimate one) began to fall apart, she continued to write. Her tragic love story, Ethan Frome, was published in 1911 to much success and acclaim. Eventually, Edith and Teddy began living apart, and in 1913, Edith divorced Teddy because of his unstable mental health and acts of adultery. Edith was also guilty of adultery. She had an affair with Morton Fullerton, a journalist for the London Times and friend of Henry James. (James, an American novelist, was a lifelong friend of Edith's. His writing style, known as American realism, influenced Edith's own writing.)

The French Years

After her divorce, Edith continued to visit the United States to retain her American citizenship, even though she chose to live permanently in France. During World War I, Edith established two organizations for war refugees: the Children of Flanders and the American Hostel for Refugees. She also made several visits to the French front where she distributed medical supplies and made observations from which she wrote war essays influencing Americans to support the Allied cause. Edith's war essays appeared in the book, Fighting France, from Dunkerque to Belfort (1915). As a fund-raiser she organized The Book of the Homeless (1916), an illustrated anthology of war writings by well-known authors and artists of the time. Edith won the French Legion of Honor and was awarded many decorations by the French and Belgian governments for her contributions to charity. She continued her charitable efforts after the war by providing aid to tubercular patients in France.

In 1919, Edith purchased two homes in France: the chateau Ste. Claire in Hyeres, and the Pavillon Colombe, located north of Paris. Both homes had elaborate gardens where Edith immersed herself. Because she felt as though she had been cut off from the life she knew before the war, she was anxious to re-establish friendships and stability. She began entertaining well-known literary personalities such as Walter Berry, Robert Norton, Percy Lubbock, Paul Bourget, and of course, her close friend Henry James.

Edith continued to write until her death in Hyeres, France on August 11, 1937 at the age of 75. She was buried in a cemetery at Versailles in France. All of Edith's papers and unfinished work were given to Yale University with the stipulation that certain of them not be released until 1968.

Career Highlights

After publishing her first volume of short stories, The Greater Inclination in 1899, Edith produced numerous novels, travel books, short stories (including many ghost stories), and poems. Several of Edith's novels have been made into successful plays and motion pictures by other writers.

Edith is perhaps best known for her novels depicting New York aristocratic life and the complicated struggle of the individual with the conventions of a powerful, and triumphant, moneyed class.

Edith received much acclaim for her lifelong devotion to writing. She is considered one of the leading American authors of the twentieth century. Because of her humanitarian endeavors and contributions to literature, Edith became the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate from Yale University in 1923, and in 1930 she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Table of Contents

Title

About

Part 1

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Part 2

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part 1

Chapter

1

In the days when New York's traffic moved at the pace of the drooping horse-car, when society applauded Christine Nilsson at the Academy of Music and basked in the sunsets of the Hudson River School on the walls of the National Academy of Design, an inconspicuous shop with a single show-window was intimately and favourably known to the feminine population of the quarter bordering on Stuyvesant Square.

It was a very small shop, in a shabby basement, in a side- street already doomed to decline; and from the miscellaneous display behind the window-pane, and the brevity of the sign surmounting it (merely "Bunner Sisters" in blotchy gold on a black ground) it would have been difficult for the uninitiated to guess the precise nature of the business carried on within. But that was of little consequence, since its fame was so purely local that the customers on whom its existence depended were almost congenitally aware of the exact range of "goods" to be found at Bunner Sisters'.

The house of which Bunner Sisters had annexed the basement was a private dwelling with a brick front, green shutters on weak hinges, and a dress-maker's sign in the window above the shop. On each side of its modest three stories stood higher buildings, with fronts of brown stone, cracked and blistered, cast-iron balconies and cat-haunted grass-patches behind twisted railings. These houses too had once been private, but now a cheap lunchroom filled the basement of one, while the other announced itself, above the knotty wistaria that clasped its central balcony, as the Mendoza Family Hotel. It was obvious from the chronic cluster of refuse- barrels at its area-gate and the blurred surface of its curtainless windows, that the families frequenting the Mendoza Hotel were not exacting in their tastes; though they doubtless indulged in as much fastidiousness as they could afford to pay for, and rather more than their landlord thought they had a right to express.

These three houses fairly exemplified the general character of the street, which, as it stretched eastward, rapidly fell from shabbiness to squalor, with an increasing frequency of projecting sign-boards, and of swinging doors that softly shut or opened at the touch of red-nosed men and pale little girls with broken jugs. The middle of the street was full of irregular depressions, well adapted to retain the long swirls of dust and straw and twisted paper that the wind drove up and down its sad untended length; and toward the end of the day, when traffic had been active, the fissured pavement formed a mosaic of coloured hand-bills, lids of tomato-cans, old shoes, cigar-stumps and banana skins, cemented together by a layer of mud, or veiled in a powdering of dust, as the state of the weather determined.

The sole refuge offered from the contemplation of this depressing waste was the sight of the Bunner Sisters' window. Its panes were always well-washed, and though their display of artificial flowers, bands of scalloped flannel, wire hat-frames, and jars of home-made preserves, had the undefinable greyish tinge of objects long preserved in the show-case of a museum, the window revealed a background of orderly counters and white-washed walls in pleasant contrast to the adjoining dinginess.

The Bunner sisters were proud of the neatness of their shop and content with its humble prosperity. It was not what they had once imagined it would be, but though it presented but a shrunken image of their earlier ambitions it enabled them to pay their rent and keep themselves alive and out of debt; and it was long since their hopes had soared higher.

Now and then, however, among their greyer hours there came one not bright enough to be called sunny, but rather of the silvery twilight hue which sometimes ends a day of storm. It was such an hour that Ann Eliza, the elder of the firm, was soberly enjoying as she sat one January evening in the back room which served as bedroom, kitchen and parlour to herself and her sister Evelina. In the shop the blinds had been drawn down, the counters cleared and the wares in the window lightly covered with an old sheet; but the shop-door remained unlocked till Evelina, who had taken a parcel to the dyer's, should come back.

In the back room a kettle bubbled on the stove, and Ann Eliza had laid a cloth over one end of the centre table, and placed near the green-shaded sewing lamp two tea-cups, two plates, a sugar-bowl and a piece of pie. The rest of the room remained in a greenish shadow which discreetly veiled the outline of an old-fashioned mahogany bedstead surmounted by a chromo of a young lady in a night-gown who clung with eloquently-rolling eyes to a crag described in illuminated letters as the Rock of Ages; and against the unshaded windows two rocking-chairs and a sewing-machine were silhouetted on the dusk.