2,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

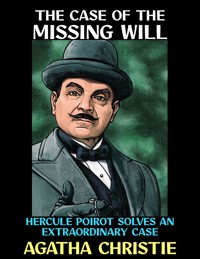

- Herausgeber: Diamond Book Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In Agatha Christie’s short story, “The Case of the Missing Will,” Poirot must help clever student Violet Marsh meet the terms of an unusual will by her Uncle Andrew. She must live in his house for a month and “prove her wits” if she is ever to receive his fortune. But is there another will? This short story originally appeared in the October 31, 1923 issue of The Sketch magazine.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Agatha Christie

The Case of the Missing Will Preview

Hercule Poirot Solves an Extraordinary Case

Table of contents

The Case of the Missing Will

By

Agatha Christie

Table of Contents

The Case of the Missing Will

The Case of the Missing Will

The problem presented to us by Miss Violet Marsh made a rather pleasant change from our usual routine work. Poirot had received a brisk and businesslike note from the lady asking for an appointment, and he had replied, asking her to call upon him at eleven o’clock the following day.

She arrived punctually—a tall, handsome young woman, plainly but neatly dressed, with an assured and businesslike manner—clearly, a young woman who meant to get on in the world. I am not a great admirer of the so-called New Woman myself, and in spite of her good looks, I was not particularly prepossessed in her favor.

“ My business is of a somewhat unusual nature, M. Poirot,” she began, after she had accepted a chair. “I had better begin at the beginning and tell you the whole story.”

“ If you please, mademoiselle.”

“ I am an orphan. My father was one of two brothers, sons of a small yeoman farmer in Devonshire. The farm was a poor one, and the eldest brother, Andrew, emigrated to Australia, where he did very well indeed, and by means of successful speculation in land became a very rich man. The younger brother, Roger, my father, had no leanings toward the agricultural life. He managed to educate himself a little, and obtained a post as a clerk in a small firm. He married slightly above him; my mother was the daughter of a poor artist. My father died when I was six years old. When I was fourteen, my mother followed him to the grave. My only living relation then was my Uncle Andrew, who had recently returned from Australia and bought a small place in his native county, Crabtree Manor. He was exceedingly kind to his brother’s orphan child, took me to live with him, and treated me in every way as though I were his own daughter.

“ Crabtree Manor,” she pursued, “in spite of its name, is really only an old farmhouse. Farming was in my uncle’s blood, and he was intensely interested in various modern farming experiments. Although kindness itself to me, he had certain peculiar and deeply rooted ideas as to the upbringing of women. Himself a man of little or no education, though possessing remarkable shrewdness, he placed little value on what he called ‘book knowledge.’ He was especially opposed to the education of women. In his opinion, girls should learn practical housework and dairy work, be useful about the home, and have as little to do with book-learning as possible. He proposed to bring me up on these lines, to my bitter disappointment.

“ I rebelled frankly. I knew that I possessed a good brain, and had absolutely no talent for domestic duties. My uncle and I had many bitter arguments on the subject, for though much attached to each other, we were both self-willed. I was lucky enough to win a scholarship, and up to a certain point was successful in getting my own way. The crisis arose when I resolved to go to Girton. I had a little money of my own, left me by my mother, and I was quite determined to make the best use of the gifts God had given me. I had one long final argument with my uncle. He put the facts plainly before me. He had no other relations, and he had intended me to be his sole heiress. As I have told you, he was a very rich man. If I persisted in these ‘newfangled notions’ of mine, however, I need look for nothing from him. I remained polite, but firm. I should always be deeply attached to him, but I must lead my own life. We parted on that note. ‘You fancy your brains, my girl,’ were his last words. ‘I’ve no book-learning, but for all that, I’ll pit mine against yours any day. We’ll see what we shall see.’