The City of the Sun

The City of the SunA Poetical Dialogue between a Grandmaster of the Knights Hospitallers and a Genoese Sea-Captain, his guest.Copyright

The City of the Sun

Tommaso Campanella

A Poetical Dialogue between a Grandmaster of the Knights

Hospitallers and a Genoese Sea-Captain, his guest.

G.M. Prithee, now, tell me what happened to you during that

voyage?

Capt. I have already told you how I wandered over the whole earth.

In the course of my journeying I came to Taprobane, and was

compelled to go ashore at a place, where through fear of the

inhabitants I remained in a wood. When I stepped out of this I

found myself on a large plain immediately under the equator.

G.M. And what befell you here?

Capt. I came upon a large crowd of men and armed women, many of

whom did not understand our language, and they conducted me

forthwith to the City of the Sun.

G.M. Tell me after what plan this city is built and how it is

governed.

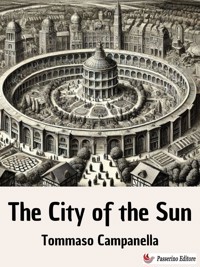

Capt. The greater part of the city is built upon a high hill, which

rises from an extensive plain, but several of its circles extend

for some distance beyond the base of the hill, which is of such a

size that the diameter of the city is upward of two miles, so that

its circumference becomes about seven. On account of the humped

shape of the mountain, however, the diameter of the city is really

more than if it were built on a plain.

It is divided into seven rings or huge circles named from the seven

planets, and the way from one to the other of these is by four

streets and through four gates, that look toward the four points of

the compass. Furthermore, it is so built that if the first circle

were stormed, it would of necessity entail a double amount of

energy to storm the second; still more to storm the third; and in

each succeeding case the strength and energy would have to be

doubled; so that he who wishes to capture that city must, as it

were, storm it seven times. For my own part, however, I think that

not even the first wall could be occupied, so thick are the

earthworks and so well fortified is it with breastworks, towers,

guns, and ditches.

When I had been taken through the northern gate (which is shut with

an iron door so wrought that it can be raised and let down, and

locked in easily and strongly, its projections running into the

grooves of the thick posts by a marvellous device), I saw a level

space seventy paces (1) wide between the first and second walls.

From hence can be seen large palaces, all joined to the wall of the

second circuit in such a manner as to appear all one palace. Arches

run on a level with the middle height of the palaces, and are

continued round the whole ring. There are galleries for promenading

upon these arches, which are supported from beneath by thick and

well-shaped columns, enclosing arcades like peristyles, or

cloisters of an abbey.

But the palaces have no entrances from below, except on the inner

or concave partition, from which one enters directly to the lower

parts of the building. The higher parts, however, are reached by

flights of marble steps, which lead to galleries for promenading on

the inside similar to those on the outside. From these one enters

the higher rooms, which are very beautiful, and have windows on the

concave and convex partitions. These rooms are divided from one

another by richly decorated walls. The convex or outer wall of the

ring is about eight spans thick; the concave, three; the

intermediate walls are one, or perhaps one and a half. Leaving this

circle one gets to the second plain, which is nearly three paces

narrower than the first. Then the first wall of the second ring is

seen adorned above and below with similar galleries for walking,

and there is on the inside of it another interior wall enclosing

palaces. It has also similar peristyles supported by columns in the

lower part, but above are excellent pictures, round the ways into

the upper houses. And so on afterward through similar spaces and

double walls, enclosing palaces, and adorned with galleries for

walking, extending along their outer side, and supported by

columns, till the last circuit is reached, the way being still over

a level plain.

But when the two gates, that is to say, those of the outmost and

the inmost walls, have been passed, one mounts by means of steps so

formed that an ascent is scarcely discernible, since it proceeds in

a slanting direction, and the steps succeed one another at almost

imperceptible heights. On the top of the hill is a rather spacious

plain, and in the midst of this there rises a temple built with

wondrous art.

G.M. Tell on, I pray you! Tell on! I am dying to hear more.

Capt. The temple is built in the form of a circle; it is not girt

with walls, but stands upon thick columns, beautifully grouped. A

very large dome, built with great care in the centre or pole,

contains another small vault as it were rising out of it, and in

this is a spiracle, which is right over the altar. There is but one

altar in the middle of the temple, and this is hedged round by

columns. The temple itself is on a space of more than 350 paces.

Without it, arches measuring about eight paces extend from the

heads of the columns outward, whence other columns rise about three

paces from the thick, strong, and erect wall. Between these and the

former columns there are galleries for walking, with beautiful

pavements, and in the recess of the wall, which is adorned with

numerous large doors, there are immovable seats, placed as it were

between the inside columns, supporting the temple. Portable chairs

are not wanting, many and well adorned. Nothing is seen over the

altar but a large globe, upon which the heavenly bodies are

painted, and another globe upon which there is a representation of

the earth. Furthermore, in the vault of the dome there can be

discerned representations of all the stars of heaven from the first

to the sixth magnitude, with their proper names and power to

influence terrestrial things marked in three little verses for

each. There are the poles and greater and lesser circles according

to the right latitude of the place, but these are not perfect

because there is no wall below. They seem, too, to be made in their

relation to the globes on the altar. The pavement of the temple is

bright with precious stones. Its seven golden lamps hang always

burning, and these bear the names of the seven planets.

At the top of the building several small and beautiful cells

surround the small dome, and behind the level space above the bands

or arches of the exterior and interior columns there are many

cells, both small and large, where the priests and religious

officers dwell to the number of forty-nine.

A revolving flag projects from the smaller dome, and this shows in

what quarter the wind is. The flag is marked with figures up to

thirty-six, and the priests know what sort of year the different

kinds of winds bring and what will be the changes of weather on

land and sea. Furthermore, under the flag a book is always kept

written with letters of gold.

G.M. I pray you, worthy hero, explain to me their whole system of

government; for I am anxious to hear it.

Capt. The great ruler among them is a priest whom they call by the

name Hoh, though we should call him Metaphysic. He is head over

all, in temporal and spiritual matters, and all business and

lawsuits are settled by him, as the supreme authority. Three

princes of equal power—viz., Pon, Sin, and Mor—assist him, and

these in our tongue we should call Power, Wisdom, and Love. To

Power belongs the care of all matters relating to war and peace. He

attends to the military arts, and, next to Hoh, he is ruler in

every affair of a warlike nature. He governs the military

magistrates and the soldiers, and has the management of the

munitions, the fortifications, the storming of places, the

implements of war, the armories, the smiths and workmen connected

with matters of this sort.

But Wisdom is the ruler of the liberal arts, of mechanics, of all

sciences with their magistrates and doctors, and of the discipline

of the schools. As many doctors as there are, are under his

control. There is one doctor who is called Astrologus; a second,

Cosmographus; a third, Arithmeticus; a fourth, Geometra; a fifth,

Historiographus; a sixth, Poeta; a seventh, Logicus; an eighth,

Rhetor; a ninth, Grammaticus; a tenth, Medicus; an eleventh,

Physiologus; a twelfth, Politicus; a thirteenth, Moralis. They have

but one book, which they call Wisdom, and in it all the sciences

are written with conciseness and marvellous fluency of expression.

This they read to the people after the custom of the Pythagoreans.

It is Wisdom who causes the exterior and interior, the higher and

lower walls of the city to be adorned with the finest pictures, and

to have all the sciences painted upon them in an admirable manner.

On the walls of the temple and on the dome, which is let down when

the priest gives an address, lest the sounds of his voice, being

scattered, should fly away from his audience, there are pictures of

stars in their different magnitudes, with the powers and motions of

each, expressed separately in three little verses.