9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

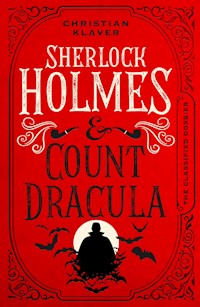

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Told through four interlinked cases, this Gothic horror mystery sees Sherlock Holmes and Count Dracula join forces to banish a terrible enemy1902. Sherlock Holmes's latest case begins with a severed finger. With no signs of decomposition and an adverse reaction to silver, it is the most perplexing mystery yet – one that relates to their next client – and the moment Sherlock's and Watson's lives are irrevocably changed.A Transylvanian nobleman called Count Dracula arrives at Baker Street seeking Sherlock's help, for his beloved wife Mina has been kidnapped. But Dracula is a client like no other and Sherlock and Watson must confront – despite the wild, unbelievable notion – the existence of vampires. And before long, Sherlock, Watson and their new vampire allies must work together to banish a powerful enemy growing in the shadows…

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Part One: Count Dracula

Chapter 01: Lestrade’s Package

Chapter 02: Carfax Estate

Chapter 03: Vampires

Chapter 04: Dracula’s Story

Chapter 05: The Tobacconist’s Shop

Chapter 06: Decisions

Part Two: The Innsmouth Whaler

Chapter 07: The Hôtel Du Château Blanc

Chapter 08: Miss Lucja Nowak

Chapter 09: The Bountiful Harvest

Chapter 10: The Depths

Part Three: The Adventure of the Lustrous Pearl

Chapter 11: The Pearl

Chapter 12: Fairview House

Chapter 13: Randall Thorne

Chapter 14: Susana Ricoletti

Chapter 15: The Merry Widow

Part Four: Old Enemies

Chapter 16: New Friends

Chapter 17: The New Baker Street Irregulars

Chapter 18: Gravesend

Chapter 19: Guests Both Welcome and Unwelcome

Chapter 20: The Chase

Chapter 21: Denouement

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Sherlock Holmes and Count Dracula

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781789097122

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789097139

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: September 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

© Christian Klaver 2021

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Case design by Julia Lloyd. Images © Shutterstock.

To my wife, Kim, for all her love and supportfor all these years.

INTRODUCTION

Astute readers will notice several discrepancies between this text, my previous stories, and the Stoker novel bearing Dracula’s name.

On the Stoker text, I can only beg the reader’s indulgence and state that there are several inaccuracies, not the least of which is the report of Dracula’s untimely demise.

As to the inconsistencies in my own text, particularly surrounding Mary Watson née Morstan, I have been forced to change many dates and names in order to preserve the privacy and dignity of several of Holmes’s original clients, muddling both the timeline in this tale as well as in my original stories. The particularly scholarly student of Holmes’s cases will no doubt note that there are several instances chronologically after The Sign of the Four in which Mary does not appear, one of the many inconsistencies to which I refer. Again, I can only beg the reader’s indulgence, but these small trivialities are necessary to preserve the secrecy under which Holmes and I have been sworn on many of his most delicate cases.

And some readers will already be familiar with Holmes’s “black box”, that depository of cases that included such wonders as “The Giant Rat of Sumatra”, as well as the separate matters involving Mr James Phillimore, and the cutter Alicia. These accounts have yet to see publication, since their grotesque and outré nature would stretch the reader’s sensibilities beyond any normal boundaries. They are, in a word, unbelievable, and I have held these cases in abeyance at Holmes’s request to protect both his reputation and my own small credibility as narrator. But the time has come, finally, to reveal them, as per Holmes’s instructions. I follow these instructions faithfully and humbly, and let my readers judge if we have done wrong to withhold them for as long as we did.

– JOHN H. WATSON, M.D.

Chapter 01

LESTRADE’S PACKAGE

It was late in 1902 when I found myself a resident once more in my quarters at Baker Street. My wife, Mary, was spending some months out in the country visiting the Forresters, and this gave me the opportunity to renew my acquaintance with Holmes to such a degree that I almost felt I had come back to bachelorhood on a permanent basis. On the third day, a tempestuous London storm howled through the chimney and tapped with wet fingers at the windows of our drawing room, making it a distinct comfort for us to be indoors.

But if the conditions appealed to me, they did not bring solace to Holmes. He had no active case at present and was quite beside himself with a hectic lassitude that had him twitching restlessly in his chair. I had tried, earlier in the afternoon, to regale him with a humorous anecdote from home, one with Mary packing up half of our domestic life to take with her into the country, but I let the story trail off when Holmes showed every sign of distraction. Several times he cast a reckless glance at the door or the window, as if expecting some interruption.

“I am a little jumpy, at that, Doctor,” Holmes said with a laugh, and I knew he had deduced my thoughts in that uncanny way of his. “It is only this dreaded inactivity, Watson. It exhausts me as work never does. It is doubly vexing when I know that trouble is brewing on the horizon, only I cannot get my hands on any of the threads, so that I have nothing with which to occupy my waiting hours.”

“Trouble?” I said. I had been at Baker Street for nearly three days, and had the feeling that Holmes had been waiting for something all this time, but he had refused to be drawn out on the subject until now.

“You are unfamiliar with my cases of the past few months, Watson, so I cannot expect you to know my current state of affairs. Of late, I have been involved in several cases that seemed, on the surface, unrelated, but which, I have become convinced, all stem from a single source. I have been seeking them out exclusively, and turning all other unrelated cases away. The missing crews from the Matilda Briggs and the Demeter, certain tangential persons involved in the death of Radghast the booking agent, and the disappearance of Miss Violet Bell are all the work of one mastermind, Watson. It is all connected, and I am carefully drawing all the threads round me, feeling for the spider at the centre.”

“Some new criminal mastermind? I thought you had rid London of any such pestilence.”

Holmes reached out and picked up his briar pipe. He scraped his pipe bowl clean and made ready for a fresh batch of tobacco by the expedient of rapping the bowl against the table leg, heedless of the shag bits on the carpet. He fired his pipe to the desired pitch before answering.

But his answer was interrupted by voices from below.

“At last,” Holmes said, with no small amount of relief. “Let us see how Lestrade’s come along with my little errand. If his urgency is any indicator, he may well have something of interest.”

I did not know to what errand my friend might be referring, yet I could not help but feel a great sense of relief, for Lestrade’s involvement meant a case of some sort. Holmes flashed me a wry smile, which was then gone in an instant. He’d noted my grateful exhalation and known the cause at once.

When Lestrade himself burst into our sitting room, the little detective wore the most solemn expression. In his hand he bore a small veneered case, such as a well-to-do gentleman might use to carry cards or cigarettes.

“Murder then,” Holmes said. “And it took you somewhat out of your way, into the Farringdon district, I should say.”

Lestrade started. “I’m familiar with your cunning ways, Mr Holmes, but how you could know all that without yet hearing or seeing any of the clues is quite beyond me.”

“You brought the clues in with you, Lestrade,” Holmes said with a wave of his hand. “It is no secret that they’ve torn up the pavement in order to begin construction in Farringdon, and in doing so thrown up a great deal of the red clay that I see about your shoes. I know your route was to Norwood, as I sent you there, and Farringdon is well out of the way. The fact that it is still wet and that you were in too much of a hurry to do more than a casual scraping at our doorstep increases the impression of great urgency. Also, your face and demeanour suggest something disturbing, despite your many years with Scotland Yard. What else but murder?”

“Well, I suppose my face does tell the tale plainly,” Lestrade admitted. “I expect you remember Stross, the forger in Norwood that you turned us on to last week?”

“Yes, quite,” said Holmes. “Did you find him at the address I gave to you?”

Lestrade nodded. “We did, and in the process of apprehending him we came upon something murkier than a simple forgery. When asked about it, the rascal would say nothing. This is a man who would send either of us to the bottom of the Thames without the slightest hesitation. To make matters stranger, this cool customer, who hadn’t broken so much as a sweat during his arrest, actually broke down in tears when we questioned him about it!” The little detective held up the cigarette case. “We have been able to get nothing intelligible from him.”

“And this is the item here?” Holmes asked. He gestured at the cigarette case.

“Yes,” Lestrade said. “I’ve taken the liberty of bringing it with me.”

“Let us see what we can make of it,” Holmes said, rubbing his hands together as he warmed to his task. Lestrade handed the cigarette case over without further comment.

“Lacquered teak,” Holmes said. “Expensive, but not otherwise extraordinary. It has seen some use by a man once wealthy who has since fallen on hard times. The clear markings of an amateurish repair applied to the hinge tell us that. Now then, let us look inside.” He fell abruptly silent when he opened the box.

I shifted in my seat to get a closer look and gasped as the significance of what I saw struck home to me. “Good Lord, Holmes!” I said, for rarely had I seen a more shocking example of brutality and horror.

Inside, nestled neatly in red velvet like a rare jewel, lay a freshly severed human finger.

Holmes leaned closer, deeply affected not with shock or disgust, but with eager interest. He pulled his lens from a drawer and examined it all together first, then carefully removed the finger. He looked further into the box and made a satisfied noise. “This was originally used for cigarettes, as one might expect,” he murmured. “Traces of them are still here.” He carefully pulled a scrap of tobacco out and snuffed at it like a bloodhound. “An unusual and expensive brand. Made in India and not much seen in England. It has a very acrid taste that would not be popular.”

Then he began a minute study of the finger itself. It was clearly a woman’s finger, and showed no sign of decay that I could see. The hand it was taken from must once have been long and white, a beautiful sight before this horrible disfigurement had taken place. Holmes measured the length and width of the finger and even scraped underneath the fingernail, which was long and unpainted.

“The ring finger of the left hand,” he murmured. “Very recently cut. It is difficult to be certain, since the cut has fallen very close to where a wedding ring would lay, but I would say that we are missing any sign of the indentation such a ring would make, so we can safely assume she was not married. The finger has no calluses, so we now have either a woman of the higher class or an invalid excused from menial labour. Very curious.”

“What could anyone want with such a grisly trophy?” I asked. “Was it some kind of proof of kidnapping?”

Lestrade shook his head. “I have not yet had the chance to communicate with any other departments in the city, but there’s no such missing person that we know of, and no ransom note was found. Nor do we have any idea who might receive one until we identify the victim.”

Holmes shot an acute glance at Lestrade. “When did you get this?”

“We found it this morning, when the arrest was made. After finding this little bit of nastiness, we searched the house, but to no avail.”

Holmes frowned, clearly displeased with this information. He sprang up and went over to the table in the corner that held his equipment for chemical experimentation, taking the box and finger with him. He rummaged among the retorts, test tubes, and little Bunsen lamps before extracting three empty tubes. He added a small amount of water to each, then carefully added a sample of blood taken from the finger to the first, and a sample from the box to the second. For the third, he jabbed a bodkin into his own finger to supply a few drops. He absently covered the self-inflicted scratch with a piece of sticking plaster, a habit I knew he performed in order to prevent accidentally poisoning himself while handling toxins. Then he measured a small amount of white crystals, dropping them into the waiting vessels. He followed this with a few drops of a transparent fluid from an angular green bottle.

He jerked upright as each and every test tube turned a dull mahogany colour. “I really must thank you, Lestrade,” he said without lifting his eyes from the experiment on the table. “Already this case is showing an extraordinary number of interesting features. Some very interesting features indeed, including some I’ve never seen before. Perhaps a case unique in the annals of crime detection.”

“Indeed,” I said fervently. “I can hardly imagine a more cold-blooded act. What kind of monster could carry around such a thing the way another man carries cigarettes? It is barely imaginable.”

Holmes waved a hand dismissively. “Oh, that is hardly exceptional. Recall, Watson, when the fifty-year-old spinster, Miss Susan Cushing, received a parcel in the post which turned out to contain two severed human ears packed in coarse salt and I think you will have to concede my point. No, it is the curious condition of the finger and the nature of the victim that interests me.”

“We must help her, Holmes,” I urged. The image of some poor woman maimed in such a fashion shook me to the core.

“I’m afraid,” Holmes said, not unkindly, “it is all too likely that this particular woman is beyond our reach to help, but possibly we can be of some assistance in punishing the criminals involved.”

“Begging your pardon, Mr Holmes,” Lestrade said, “but the woman may still be alive. I would hardly call that wound fatal.” He had taken his hat off and was currently worrying into a sorry shape in his idle hands while he watched Holmes.

“No,” Holmes said. “You wouldn’t, but I consider it the highest probability.” He held up a hand to fend off further protests. “You have your methods, Lestrade, and I have mine. Be assured that I will send you a telegram with any advice or information that I have, as soon as I am sure of my facts.” With that, he bent back over the gruesome piece of evidence, fishing out more test tubes for further experiments. Lestrade and I were clearly forgotten and dismissed from his thoughts.

Seeing it was no use to protest further, and that Holmes would not have any information coaxed out of him until he was ready, Lestrade gave a displeased grunt, crammed his hat forcefully back onto his head, and left.

Holmes spent the rest of the evening at work, completely ignoring the arrival of dinner. The parlour filled with an ever-increasing cloud of noxious smoke as he applied test upon test to his specimen. The miasma was augmented even further as he took more and more frequent breaks to sit and ponder, puffing away at his pipe until the haze became intolerable. It had gone past a three-pipe problem and well into a seventh when I finally gave up trying to read through the smoke and went to bed.

* * *

When I awoke in the morning, Holmes’s chemical experiments were still underway, and the darkened room was dotted in that corner with the little blue flames of multiple Bunsen burners going at once. Holmes was not at the table, but wandered about our quarters with an air of extreme agitation. He smoked the old clay pipe, the foulest of his collection and the room was wreathed in blue smoke.

“Aha, Watson,” he said at once. “Clearly this case goes deeper than I first suspected.” He pointed with the pipe. “Take a look at our unique evidence and give me your thoughts on it.”

Hardly knowing what to expect, I went to the table and bent over to look at the finger laid upon a Petri dish. The blood still glistened brightly at the severed joint without any sign of coagulation or clotting. Nor did it seem to show any signs of decomposition.

“Why, it looks as if it was freshly severed this morning!” I exclaimed.

“Exactly!” he said. “The blood has not dried or congealed, as we might expect. You may recall that I questioned Lestrade as to how long he’d had the finger in his possession. This was because it looked unusually fresh.”

“A haemophiliac?” I asked.

“My thoughts precisely, though this kind of bleeding is exceptional even for such a patient. Female haemophiliacs are nearly unheard of, as I’m sure you know. Also the blood has several other irregularities. You yourself saw that it passed the Holmes blood test I perfected the day we first met, just before we became involved with the affair of Major Sholto, of Upper Norwood.”

“I remember it well.” How could I not, having also met my wife during those events?

“But the blood from this finger does not seem to correspond to most of the other characteristics of human blood, nor does the flesh of the finger precisely correspond to normal flesh. Whatever disease could change this person’s chemistry rather thoroughly, so it must have been long-term, rather than something recently contracted. It is also curious that, though there is still some evidence of blood flow, the rest of the finger is quite desiccated, though it hardly looks it. I noticed this because the finger is much lighter than I should expect. It is also strangely resilient. There are indications that this may also be true in life, and that the disease dramatically alters the circulatory system as it progresses. This agrees with the differing characteristics of the blood. You will remember that I commented to Lestrade that the removal of a finger might, in this case, be fatal. Such is the nature of haemophilia.”

“I do,” I said. “To what characteristics of the blood do you refer?”

“Well,” he said with a sly smile. “There are several. But this demonstration is the most striking.” He took a small specimen knife and cut a portion of skin off the finger, adding this to a test tube that already had a clear liquid in it. He then sprinkled a small amount of a light grey powder into the solution and immediately a violent bubbling eruption occurred. In but a few moments’ time, the reaction had ceased and I was able to see into the clear liquid that remained. The skin sample was gone, quite dissolved into the solution.

“What did you put in?” I asked. “Some destructive acid compound?”

Holmes went back to his pipe and got it going again before he answered. “Powdered silver,” he finally answered. “Discovering this reaction was more accident than method, I must admit.”

“Silver…” Nothing in my long medical history, nor in my unusual dealings alongside Sherlock Holmes, had prepared me for so extraordinary a statement.

“Yes, I quite understand your reaction,” Holmes said. “All this leads us to infer the existence of a sufferer of an as yet unknown blood disease that leaves the victim so robust that a young woman is still capable of an active climb that would strain even an accomplished athlete.”

“Climbing? But how on earth could you know that?”

“There are abrasions on the skin and, as well as traces of stone fragments both within the abrasions and underneath the fingernail. Not all of these are new, which suggests more than one such climb in the recent past. At first, I considered the possibility that she had been shut behind a stone door, or some other explanation for the abrasions, but the abrasions lead me to believe that the activity must have been climbing. You recall that I said there were no signs of the regular calluses that usually accompany the physical activity I would associate with a working woman. In addition, a professional climber would have specialized calluses, very hard and smooth, and there are no signs of these, either. This indicates either a woman of the higher class or an invalid excused from menial labour. Either answer seems at odds with our climbing theory, does it not? Or at the very least an unusual combination.

“Most blood diseases are debilitating to the victim,” I said, incredulous. “I can hardly imagine such a person making a strenuous climb.”

“Nor can I,” Holmes said. “Yet I can find no other explanation which meets the facts that are presented to us.”

“Good Lord,” I said, remembering the prominence of haemophilia in the royal family. “You don’t suppose that this woman could have been royalty.”

“I consider it highly unlikely,” Holmes said. “Remember, there was no sign of any jewellery, which makes it unlikely to be someone from court.”

“What does this all mean?”

“We do not have enough data for a complete determination,” Holmes said. “But I have several lines of inquiry. I believe that my next step is to visit West Sussex, where I know a man who deals exclusively in Indian cigarettes. One of the few places in England that carries this distinct tobacco.”

“Then I shall come with you,” I offered.

“That is by no means necessary. I think you would find this preliminary investigation very tedious, and there is not likely to be any danger at this stage. Also, I will send out several telegrams to other tobacconists, and I will need someone reliable to await their reply. But keep your revolver ready, Watson! With such a clue as this first one, I have no doubt that I shall have need of it, as well as your firm resolve, before this case is concluded.”

Chapter 02

CARFAX ESTATE

I spent the rest of the day without further news, and the only break in the monotony came when a small package arrived for Holmes from the Ingerson Rifle Company. Having been given directions to intercept all of Holmes’s mail for him, I opened the package with trembling hands, lest another severed body part should await me. Instead, I found a card from the company with a short note: “Per Your Instructions – Ralph Ingerson” and two small boxes. I opened these and found that they were laden with gun cartridges. But no ordinary cartridges. While the casing looked normal enough, the bullets themselves gleamed and shone, even in the moderately lit study. Silver. Of course, I made the connection between these and the unusual reaction to silver in Holmes’s test, but I couldn’t for the life of me imagine how that could make this kind of ammunition necessary. A bullet of lead would serve just as well, I should think, and besides I could hardly imagine an instance where we might need to shoot the victim of the case. Deciding that this portion of the matter was quite beyond me, I set the package aside and continued to wait.

No sign of Holmes came, and Baker Street received no further correspondence that night, but a telegram was waiting for me when I woke the next morning. It read thusly:

Come down to the Kensington Hotel near Kirby Cross train station in Essex County at once. Will send a cab. Come armed. Bring Ingerson package. SH.

I had Mrs Hudson send for a cab immediately. My old army habits stood me in good stead, and I was able to get my things together quickly enough to be ready for the driver when he pulled up to our kerb.

* * *

It was only a few hours later when I stepped out of the train and onto the platform at Kirby Cross. I hefted my luggage and found a cab waiting for me. The driver, a large fleshy man, grunted when I requested the Kensington Hotel and departed immediately. In just a few short minutes I saw a hotel sign, but was amazed when we rattled directly past it without pause or even any sign of slowing. I hammered my cane on the roof of the hansom, but the driver ignored me utterly. I was quite beside myself, particularly since we seemed to be entering a seedier and more disreputable part of the sleepy county. The hansom finally came to a halt underneath a huge yew tree. I burst out of the cab and shook my stick at the driver.

“See here, man!” I said. “What is the meaning of this?”

The driver was hunched over with his face in his hands, and I saw him pull something wet from the front of his mouth and then drag off a heavy wig. When he turned, I was astonished to see Sherlock Holmes smiling down at me.

“Forgive me, Watson,” he said with a chuckle, “but I did think you would rather come to the heart of the investigation at once.” He dropped the wig at his feet, and stuffed the cotton wads that he’d used to help change the shape of his face into his pocket.

“Good Lord!” I said, quite astonished.

Holmes next discarded the shabby outer garment he’d used as part of his driver’s disguise and stepped down from the box only to usher me back inside the cab. When he followed me and shut the door behind him, his face had a deadly earnestness to it.

“I should warn you, Watson, that this case is possibly the murkiest, most sinister case in which we have ever been involved. My plan is for you to wait here and provide a rear guard while I investigate inside.”

“Couldn’t I be of far more assistance inside?”

“Perhaps,” he admitted, “but this is one time that I fear the risks are far too great, and I haven’t the time to explain them. It is already past noon, and we shall need every minute of the remaining day.”

“If there is danger,” I said stoutly, “then that is all the more reason for me to come with you. I quite insist!”

He gripped my arm in camaraderie. “I can always count on you, Watson. Very well. Did you bring the package from Ingerson?”

I wordlessly handed over the package of bizarre ammunition, quite at a loss as to why such elaborate precautions were necessary, but knowing that my friend would not order such a curiosity without good reason. Holmes pulled his own revolver from his jacket pocket and ejected the regular cartridges onto the cab seat and began replacing them with the silver bullet cartridges from the package. He gestured for me to do the same.

“Let me fill in the new details of this investigation,” he said. “The case containing the finger was clearly used previously for the far more mundane purpose of holding cigarettes, yet Stross, our forger, does not smoke. So I theorized that the Indian tobacco found in the case might lead us to the finger’s source. I resolved to trace the recent sale of the Indian tobacco, which led me to several unremarkable places, but also to here, the Carfax Estate. I have found a number of subtle and disturbing characteristics of this property, which belongs to the Lady Willingdon, an elderly widow who has been gone for some months visiting in Europe. She is unharmed and whole with all her fingers as of yesterday, according to the French officials that I telegraphed. Denied her inheritance because of her sex, she still has some wealth, but owns very little property in England. This is her sole estate, and she only has this because it was awarded back to her, after previously being sold to a foreign dignitary. Due to a legal miscalculation and the lack of said dignitary having any presence or legal representation, the sale was considered illegal, and came back to the lady some time ago. Neither she nor anyone in her employ has been here in many years. According to the officials, it has been abandoned and untenanted, but I have found tracks of more than one person at the entrance, so ‘abandoned and untenanted’ can hardly be accurate. We need to find out more about whatever clandestine activity is happening here. I urge you to the highest level of caution, Watson.”

“Then whose finger…” I asked.

“That has yet to be determined,” Holmes said quickly. I knew my friend well enough to guess that he suspected a great deal more than he told me, but also knew that he always had good reasons for revealing his deductions in the proper place and time. Following Holmes had never yet given me cause for regret, and I was far too old a campaigner to change my habits now. My gun now loaded, I indicated my readiness to follow wherever he should lead.

Not since the affair with Milverton had I felt so much that our roles in society had been twisted out of shape, as if we were now the criminals instead of upholders of the law. The gate may have been rusted, but we found the lock secure with signs of recent use. I had seen Holmes pick locks with the competence of a seasoned burglar, but after examining the gate he turned aside and walked the hansom around to the back part of the stone wall and used the simple expedient of pulling the carriage close to the wall and climbing over. Should any representative of the law have come by during this time we might have found ourselves in the novel and entirely unenviable position of being arrested, but luck was with us, and such was not the case.

Holmes lowered me down with a steely grip on my arm, then dropped down beside me with ease. It never ceased to amaze me, this change from a tweedy scholar in Baker Street to active bloodhound or even criminal, if the cause was just.

“Going in this way,” he whispered into my ear, “we avoid any dogs, as well as those who might be watching the gate, since their activities are all concentrated there.” And so it was. We made our way across the unkempt grounds so overgrown with bracken and gorse and so filled with dead foliage that it might not have been tended to for decades. The grounds had to be at least twenty acres, if not more, and included an immeasurable amount of overgrown foliage, a small stream and a dark, weedy pond. The house, when it came into view, was a very large, squared-off edifice, bulky against the grey sky. As we got closer, we could see that it was a haphazard affair, with some of it fairly modern, or at least of this century, while other portions of heavy stone looked positively medieval, with few windows, and those high up and barred with rusty iron. There was no difficulty gaining entrance, however, as many of the less substantial portions of the house were in poor repair and included several broken windows and doors falling nearly off their hinges. Holmes’s fear regarding dogs proved to be unfounded, as there were none on the estate.

The inside of the house was in even worse repair than the outside garden. There was some torn and decrepit furniture, but mostly the place lay empty, as if much of what might once have been there had been carried off a long time ago. Old paint of a universally drab grey colour flaked off the walls and a smell of dust, mould and decay permeated every corner. Not a noise came to our ears except the whispering of the wind outside, and our every footsteps, which sent echoes through the apparently empty and abandoned structure.

We made our way through part of the house and found only more empty rooms until Holmes stopped me as we came upon the entrance to an old-fashioned courtyard. The doors were flung open and broken, one hanging only on a single hinge and swaying in the slight breeze. He pointed down at several sets of fresh tracks etched into the dust on the floorboards in front of us.

“Careful where you step, Watson,” he said as he crouched to a nearly prostrate position to examine them. “Two different sets of workman’s boots, one large, one even more so, both hobnailed. And an entirely different set of well-to-do gentleman’s boots. Curious…”

“Holmes, look here,” I said. From my removed position, close to the end of the hallway, I had nearly placed my hand on a crack in the wall without noticing the bullet lodged there.

“Excellent, Watson!” Holmes cried as he came back to look at my find. “Score one for you!” He pulled a penknife out and carefully pried the bullet free. “There is blood here.” He wrapped the evidence in his handkerchief and placed it in his pocket as he went back to his work on the floor. “And more blood by your foot, here.” The spot he indicated was just a few drops, but he used his knife to scrape up a sample of this, too.

“Give me a moment while I examine these markings.” His path carried him closer to the entrance of the courtyard as he examined the area in minute detail. When he looked up from the doorway itself, a shadow passed over his face, followed by a look of grim determination.

“Whatever has gone on here,” he said, “it seems that we are too late to prevent it. But perhaps not too late to deal with the villains responsible.”

Seeing that Holmes’s inspection of this portion of the floor was done, I entered the courtyard.

By the doorway lay the bodies of two men, so horribly battered and bent into unnatural angles that there could be no doubt about the nature of their death or the futility of my medical services. Their faces were twisted into a shocked rictus of horror. These were men who had seen their violent deaths coming. A six-shot revolver lay just inside the doorway. Holmes picked it up, sniffed at it, then opened the cylinder. All the bullets were still in place. He tucked it into his jacket pocket.

Then, in the centre of the courtyard, I caught sight of the third body, though it was nearly unrecognizable as such, being so badly charred. In an act of further barbarism, a stake had been driven completely through the unfortunate victim’s torso, pinning it to a long plank that lay on the ground. Though I have seen many horrors in my career between Afghanistan and the innumerable cases in which I’ve assisted Sherlock Holmes, none of them chilled my soul in the same way that this scorched cadaver did.

“Holmes!” I said in a choked voice as I noticed something that increased my horror of the charred cadaver tenfold. “Look at this woman’s hands!”

“Yes, Watson,” he said. “I was wondering if you would pick out that detail.”

“The left hand is missing the very same ring finger!” My stomach and mind churned with the fearsome image of any woman being burned to death in this manner.

“Indeed it is, Watson,” Holmes said. He picked a cigarette butt off one of the flagstones, sniffed at it, and gave a small cry of satisfaction. From there, he went through a search of the victims’ pockets, finding, in very short order, several of the distinctive cigarettes loose in one of the men’s pockets. “These are loose, but have at one time been in a cigarette case. You can see impressions from the clip used to keep the cigarettes in place. It seems very likely that this man provided that case for transport of the finger to Stross, who would then deliver it. But deliver it to whom?”

I had seen Holmes perform some thorough inspections before, but this one was exceedingly so. He took several more blood samples with his penknife, placing the contents in small tubes apparently brought for the purpose and labelling them as he went. His investigation included every flagstone and overgrown flower bed in the courtyard and even the bricks of the courtyard wall as high as he could reach. He poked, peered, and pored over every detail, even sniffing at the burnt corpse. He took longer going over this ghastly scene than I ever remembered him taking over similar scenes, muttering to himself as he went, though I could catch nothing of what he said and so was quite in the dark as to what he might have found out. It was several hours and well into the latter half of the afternoon before he completed his task.

“Well,” he said, finally, “I believe that we can do no further good here, Watson, and it is well past time that we should be on our way. I wish to get back to Baker Street as quickly as possible.”

“Have we learned nothing?” I asked. “Is there no clue to lead us to the villains that have done this monstrous thing?”

“Oh, I should say we’ve learned a great deal,” he said, “but the conclusions are so fantastic that I do not dare entertain them until I have eliminated all other possibilities.”

“You must clarify it for me, then,” I said, “for it is all a muddle in my mind.”

Holmes shook his head. “I have one further test before I can be sure.” He grabbed my arm. “Come. It is vitally important that we spare no delay.”

“Should we not at least summon the police?” I asked as we made our way out.

“That would be the worst action we could possibly take,” he said without turning or breaking stride. “I believe the official force would be well out of their depths on this case, Watson. If what I suspect is true, then only harm can come from their involvement. Come, we may take a direct route, as the gate is clearly not watched as we feared.”

He raised his hand to forestall any more questions, and we left as he had suggested without any further incident. I mounted the driver’s box of the hansom and he wordlessly handed me the reins before sitting beside me. I could see that the day’s investigations had troubled him deeply, as they certainly had me. But I had no doubt that Holmes’s keen mind had penetrated far deeper into the mystery than my own and I could see my friend grow more and more agitated as he sifted the information around in his mind.

He fidgeted and frowned all the way back to the driver station near the train, where he wordlessly handed a number of sovereigns to a large black-bearded driver for use of his cab. The man tipped his hat low and murmured his thanks, which Holmes answered with a distracted air. Holmes let me handle the purchasing of tickets and luggage arrangements. All the way back to Baker Street I held my questions as he bit at his nails and lip, tapped his fingers, but would answer none of my questions.

When we finally arrived at our quarters, it was nearly six o’clock. Holmes rushed past Mrs Hudson’s questions about supper, up the stairs and over to his chemical table.

He snatched up the case with the specimen finger in it and held it thoughtfully for a few seconds.

“There is no doubt,” Holmes said, as if continuing a conversation from before, only I had not the foggiest notion of what he meant.

“No doubt about…” I prompted.

He gave a thin smile. “I’ve been far too timid with my deductions on this case, Watson. To begin with, while there have certainly been instances of variance from one finger to the next on the hand of any one individual, there is still no escaping the fact that when a great number of discrepancies mount up, there can be but one conclusion.”

“I’m afraid you’ve lost me entirely, Holmes.”

“This finger is not a match for the finger missing from the charred remains we found today.”

“Not a match?” I said, surprised beyond reckoning. “Could there be a mistake, caused by the corpse having been burned as it was?”

“Come now, Watson,” Holmes said, a little pained. “You cannot think me such a bumbler as to not account for that. But while the flame would, without a doubt, shrivel the skin and flesh and even, to a lesser extent, the bone, you cannot expect the process to lengthen the bones of the hand, can you? Our finger here is simply not a match.”

“Then there are two severed fingers in this case?”

“So it would seem.” He frowned. “And yet… yet, that is not the part of this case that perplexes me the most.” His expression, usually so masterful while on a case, was filled with indecision.

“What, then?” I said.

But he shook his head and set the cigarette case down. Then he stalked over to the table and snatched up his Stradivarius. Falling into his chair, he began to pluck at the strings in the most desultory and, frankly, irritating manner. He turned away from me as he did so, watching the fading light out the window. I knew better than to press him for answers, so I opened the paper and began to browse for something to occupy my attention while I waited for Holmes to come around.

No sooner had I flipped the paper to the second page than Holmes jumped to his feet, dropped the violin unceremoniously back onto the table, and turned to face me with a dramatic air. The indecision had entirely left his face.

“Watson, what do you know about vampires?”

“Vampires?” I repeated. I’d been prepared for something unusual, but this was a staggering proposition coming from the logician. “Nothing more than fanciful stories. But why ask me such a question? You yourself have called the very notion rubbish!”

“True,” he said, ruefully. “But now I am forced to revise my opinion in the light of overwhelming evidence. Consider the facts, Watson. You have already conceded the existence of a rare blood disease. We have samples, and have seen evidence of it.”

“Quite true, but, Holmes… vampires?”

“Bear with me, Doctor,” he said. “I have determined that the nature of this blood disease greatly affects the cell structure of its victims, replacing the chemical structure of the cell in such a way as to completely transfigure its makeup. You have already seen the violent reaction to silver.”

“I am hardly in a position to argue,” I said reluctantly.

“Agreed. Now… is it such a reach to suppose that such a victim might have entirely different dietary needs?”

“But, Holmes,” I cried. “Drinking blood? Bats? Mist? Wolves? Frightened of the holy cross? Bursting into flame in sunlight? Surely this is madness!”

“Clearly we can’t condone all these beliefs, Watson. Not in our orderly world. But let us take the last question first. I spent all night going over this sample of our haemophiliac, Watson. All night. I managed to discover the unusual reaction to silver, but there is one test I did not think of, and perhaps it may be the most conclusive.”

With a swift motion, he picked up a scalpel and cut off a small portion of the finger and placed it on a small dish. He then placed the dish on the corner of his chemical table, near the window, where the last bit of daylight shone on it.

“We might have done this accidentally,” Holmes murmured, “if not for the abysmal weather.”

“What in the world?” I said, sitting bolt upright as a small curl of smoke puffed from the dish. The sample burst into low flame, then went up in a cloud of acrid smoke like a Chinese firework gone horribly awry. Smoke plumed up from the table, and we were both coughing uncontrollably before Holmes managed to cover it with a metal serving lid in order to smother the flame. Even so, we had to stumble around opening windows and waving sheaves of paper to drive out the smoke, and it took a great many minutes to clear our sitting room.

“Well, Watson,” he said with a wry smile as we fell back into our chairs. “It seems my flair for a dramatic demonstration has somewhat backfired on me. Yet, clearly you will have to concede that there must be more to this vampire business than we at first believed. This also indicates, when you consider the details of the woman in the courtyard’s death, that we have not one vampire, but two in this case. Each of them missing a finger.”

“I don’t know what to think,” I said. “I cannot fathom how this could possibly be. If it were true, why has there been no outcry other than a collection of old fairy tales and that Polidori twaddle?”

“I’m inclined to think that this condition is rare, and the numbers of the afflicted must be very small,” Holmes said.

“What you say must be true,” I said, “but I still cannot bring myself to fully comprehend the undead. I simply cannot imagine how this could be, and yet I must.”

“I think, perhaps, ‘undead’ is a term that is best discarded,” Holmes said. “Vampires, or those infected with this blood disease, are remarkable, but still human and still fall in the purview of science rather than superstition.”

“But what of the rest?” I said. “Turning into mist, or a bat, or being repelled by the holy cross?”

“I should think that we are not quite forced to accept all of the information that comes to us without some examination as to its merit. It occurs to me that some portions of these lurid tales are rife with more superstition than logic. The power of the cross to hold such a fiend, for example. Why should this be? But when you consider that many such crucifixes are made with silver, and that this material might well give such an assailant pause, this I can credit. But I am ahead of myself, Watson, and it is a mistake to theorize too heavily without all the data.”

“But how did you know? How could you possibly have come to this impossible conclusion?”

“How indeed?” said a sonorous, cultured voice.

I sat bolt upright at this sudden intrusion, so startling was it. Holmes was even more galvanized, and leapt to his feet.

The man standing in our doorway was tall, taller even than Holmes, and equally gaunt. His features were sharp and strong as well, but there the similarities diverged. Instead of Holmes’s lean, ascetic features, this man’s bushy eyebrows, long black moustache and great mane of black hair combined to create an impression of fierce grandeur. Like a barbaric king he was, noble and proud without a trace of shame, and clad in a black cloak over a dark, sombre, expensive suit that looked many years out of date. The spatter of the rain and crash of thunder came loudly through the still-open window, which was curious in itself, as there had been little foreshadowing of such a storm.

“Be wary, Watson,” Holmes said levelly. “We are in grave danger here. Consider the noise on the steps.”

“But I heard nothing!” I said, quite taken aback at this unreal series of events.

“Precisely.”

“You are an interesting man, Mr Holmes,” the intruder said. “With a shocking clarity of perception.” His English was excellent, but the intonation marked him clearly as foreign. He moved idly towards the window, as if unaware of his actions, and Holmes took several corresponding steps towards his desk. I was keenly reminded of two predators, the bloodhound and the wolf, stalking each other with deadly intent and malice.

“But, I assure you that your wariness is not necessary,” the man said in a conciliatory tone. “Please sit, I mean you no harm.”

Holmes moved behind his desk and picked up the revolver there. I made to follow suit. I still had the gun in my jacket pocket, and it would have been a moment’s action to stand and draw it. When I tried, however, I found I could do nothing of the sort. I could not even take my eyes off the man’s own, which burned like coals in the low flickering light of the small hearth fire we had burning. It was dark outside, which I hadn’t noticed until now, and our comfortable sitting room in Baker Street felt transformed, a fragile and uncertain shelter in a dark and menacing world.

“That is quite enough,” Holmes said, proving his own mobility by raising and cocking the gun in his hand.

“Guns mean little to one such as…” the man started, but his voice trailed off as Holmes calmly held up a bullet between thumb and forefinger. Even in the flickering and dim light, the gleam of silver was apparent.

“Most exceptional…” the man said. “A keen and disciplined mind, not to be distracted or diverted from its purpose.” He smiled, and some tension in his eyes seemed to relax its grip. I found that I could move again. I sprang to my feet and yanked out my own revolver. Holmes held up a restraining hand, though, so I took no further action.

“You know my name, of course,” the man said, still quite at ease.

“I do not know anything other than the fact that you are a foreign noble whose tastes run to extravagant means, but who has not been exposed to London society for some time. You are quite old, much older than you appear, and you are used to being obeyed implicitly. You have few servants, but the ones you have are fiercely dedicated. You travelled here without carriage or hansom, and have spent much time walking the London streets. You’ve had some recent distress, but that is not entirely what brings you here. I know that your disease has made you something both more and less than human.”

“Ah… not so well informed as I thought,” the man said. “I was sure that Van Helsing or Holmwood would have told you that much, at least.”

“At this time three days ago I knew nothing of the matter,” Holmes said. “And those names mean nothing to me. I have drawn my own conclusions as to your nature based on the evidence.”

The man’s face broke for just an instant, and a wild and feral look came over him. His mouth opened in the beginnings of a snarl, and the shocking white teeth sent gooseflesh down my back. But just as quickly, the man stopped, and his face resumed its look of caged civility again. There was a long moment’s pause in which he seemed to have a great internal struggle.