9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

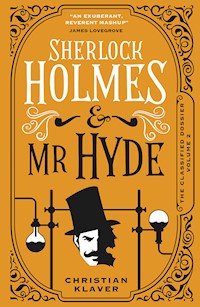

A deftly crafted, scintillating mash-up of Victorian mystery and horror – Sherlock Holmes and Mr Hyde encounter villains with unfathomable, terrifying abilities…1903. A darkness has descended on London. A series of grisly murders are uncovered, trophies taken, bodies arranged and soon there are whispers of Jack the Ripper's return.A new client arrives at Baker Street seeking Sherlock Holmes's help: Dr Jekyll claims his friend has been wrongfully accused of the hideous crimes, a friend called Mr Edward Hyde, whose very existence relies on a potion administered by the doctor himself.But the case becomes more complicated, more unsettling than simply proving Mr Hyde's innocence – for Holmes and Watson unearth beastly transformations, a killer who moves unseen, a secret organisation and then find a traitor in their midst…

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Also by Christian Klaver and Available from Titan Books

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Part One: Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Chapter 01: The Return of Jack the Ripper

Chapter 02: Hyde’s Story

Chapter 03: The First Murder Scene

Chapter 04: Whitechapel

Part Two: A Campaign of War

Chapter 05: The Second Murder

Chapter 06: Mayhem on the Rooftops

Chapter 07: The Beast

Chapter 08: Madam Clementine Fleete

Part Three: The Cult Strikes Back

Chapter 09: The Esoteric Order of Dagon

Chapter 10: Traitor in Our Midst

Chapter 11: We Lose One of Our Own

Chapter 12: Beechwood Manor

Part Four: The Order of Cthulhu

Chapter 13: The Invisible Man

Chapter 14: The Cult Revealed

Chapter 15: Aftermath

Notes on the text to the Astute Reader

Acknowledgements

Also Available from Titan Books

Also by Christian Klaver and available from Titan Books:

The Classified Dossier: Sherlock Holmes and Count Dracula

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Sherlock Holmes and Mr Hyde

Print edition ISBN: 9781789098693

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789098709

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: September 2022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Christian Klaver 2022

All Rights Reserved

Christian Klaver asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To Dad, for instilling a love of all things Sherlock

Chapter 01

THE RETURN OF JACK THE RIPPER

During my long acquaintance with Mr Sherlock Holmes, there have been many cases where Sherlock Holmes has been thrust into the limelight, such as during ‘The Case of the Raven and the Shroud’, and also ‘The Disappearance of Mrs Graham’s Wedding’. There have also been a few cases where it has been necessary, at the request of a client who wished to keep their lofty names from being attached to a public scandal, to keep my records unpublished. But in this instance, the case itself is so famous and prominent in the public’s eye that this task is an impossible one. In addition, Holmes’s involvement was so slight and no progress was made for years, so that there was scarcely any point in constructing a narrative. Now, however, matters have finally offered a resolution of sorts after so many years. Thus, it is with some relief and some trepidation that I take up my pen to write of the grisly affair surrounding the activity known as the Whitechapel Murders, and the deeds of the persona the newspapers have called alternately the Leather Apron, the Knife and, most enduringly, Jack the Ripper.

Even though London’s most famous detective, along with Scotland Yard and a great many other law enforcement agencies, spent a great deal of time on the case, it is a matter of public record that there were few promising suspects and in the end, no arrests.

Though the facts are still fresh in the minds of many of my readers, I will lay out a short summary here.

While there was a great deal of disagreement regarding the case, Holmes posited that the murders of Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman and Catherine Eddowes could be linked to the same perpetrator, but found discrepancies when applying this same theory to the murder of Elizabeth Stride, murdered on the same night as Eddowes, and that of Mary Jane Kelly. The theory encountered even further difficulties when applied to the murder of Rose Mylett, later the same year, or that of Alice McKenzie or the nameless corpse found on Pinchin Street, both of them having died in 1889. These were lumped into the same case file, an act that Holmes found profoundly intolerable.

“The obstacle,” Holmes had confided to me shortly after the discovery of the deeply unfortunate Miss Coles, “is that the official force, Lestrade and Gregson included, are fixed on the idea that this must be one perpetrator. But I’m afraid the evidence points to a completely different conclusion. There is more than one person capable of these horrific acts. The hunt for a single murderer is flawed, for there is undoubtably more than one and the investigation will be forever hampered and ineffective if Scotland Yard does not admit to the possibility of multiple murderers.”

“To attack a woman you’d never even met before,” I mused, “to cut her throat, then defile the body afterwards in such a gruesome manner. It’s unfathomable, Holmes, for even one man to be capable of such a thing. How can you imagine two such men?”

“I do not imagine,” he said coldly. “I observe.”

It had been a bitterly cold night, I recall, and I can still see Holmes’s lean profile in the flickering firelight, his brow furrowed, his gaze deeply troubled. He had a cigarette in one hand, forgotten and burned down to a cold, ashen husk. A healthy amount of whisky in a glass sat near his other hand, equally forgotten.

“Unfathomable,” I repeated.

“Yes,” he said. “Unfathomable, and yet, it is quite true.” There was note in his voice that put me on guard, for I have long suspected that Holmes’s fierce intellect and indomitable will sheltered a sensitive nature. My fears proved completely founded, as he took to the solace of the cocaine bottle for the next two days, as I had not yet weaned him off that vile narcotic. We were both saved when the Case of the Shakespearean Spectre came to Baker Street, for which I was infinitely grateful, since I was due to be married to Mary Morstan and so abandoned Holmes and my quarters in Baker Street. But I assuaged my guilt with frequent visits and was deeply gratified to see the comfort of work replacing the drug in Holmes’s life. He did not seem the worse for wear for having Baker Street to himself.

The Ripper did not commit any further crimes that year, and our life resumed a slightly more even keel, with my buying a medical practice and settling into married bliss with Mary, while still participating in many of Holmes’s most extraordinary adventures.

In 1891, the Ripper struck again and still neither Holmes, nor anyone else, could find substantial evidence that would identify the murderer. Holmes had serious doubts about whether or not the culprit was even the same person, or persons, as before. But the Ripper, or his imitator, did not strike again after that. Then, the case of Moriarty overshadowed even the Whitechapel Murders and resulted in Holmes’s and Moriarty’s final confrontation at the Reichenbach Falls, to the supposed death of both men.

Despite Mary’s presence in my life and the solace she brought me, the three years that followed were dark for me, and it was not until 1894 that Holmes returned and I learned the truth. We did not learn that Moriarty, too, had survived until almost a decade later.

Looking over my notes, I find that this period included some of our more famous cases, including ‘The Adventure of the Dancing Men’, ‘The Problem at Thor Bridge’ and ‘The Adventure of the Illustrious Client’, where we were first introduced to Baron Gruner and Miss Kitty Winter, both of whom would make a further impact in our lives long after that first case was complete.

Then disaster struck in the year 1902 and we learned that humanity, already capable of descending to murky depths, could plummet into even darker waters. That was the year we discovered, much to our disbelief and horror, the blood disease that causes vampirism. We learned, too, that Professor Moriarty had become a vampire and thus survived his plummet at Reichenbach. He had used the intervening years to rebuild his criminal empire and turned his attention to the destruction of the one man who had thwarted him before, Mr Sherlock Holmes.

Moriarty’s first telling blow was one of enormous personal cost for my own self, as Moriarty reasoned that he could do the most harm not by striking at Holmes directly, but at those near to him. He started with my own wife, Mary, and then used her to strike at me, infecting both of us with the disease. The transformation to a vampire broke my sanity for some time, but I recovered. Mary’s personality, however, was shattered permanently. With the help of the profoundly disturbing Count Dracula and his wife, Mina, we were able to vanquish Moriarty and his horde of vampires, but Mary was forever lost to me.

Early in the year of 1903, on a dismal winter eve when neither of us had any professional engagements to force us out of doors, Holmes and I had occasion to discuss the Whitechapel Murders again. It was I who raised the subject, as the weather had fouled my mood and the Ripper seemed an atmospherically appropriate spectre. I have since wondered if this conversation bordered on premonition, as these details were destined to darken our doorstep again in a very short time.

“Holmes, have you considered the Whitechapel case any these past few years?”

At first, I thought he’d been too lost in thought to hear me, as he was scraping listlessly at his violin, making the most dismal and atrocious noises. I’d opened my mouth to ask the question again when he finally answered.

“I have, as it happens, gone over the data a number of times, and feel that a different perspective may be called for,” Holmes said. “I even had occasion to discuss it with Gregson and Lestrade the other night when you were out, so it is curious that you raise the issue now. There was a fatal flaw in my reasoning. A flaw so obvious, and yet unexamined, that it has tainted that investigation from the start. Neither Lestrade nor Gregson could see it, even after I explained it. My only consolation is that every other person involved in the case has made the exact same mistake.”

“What kind of mistake?”

Holmes put away his violin and filled his pipe, the briarwood one that had seen so much use. “I once remarked to you that the details that can make a case more sensational and outré are often the very same ones that lead most easily to a solution. It is the commonplace crimes, without any feature of distinction, that are so very difficult to solve.”

“So you have said,” I agreed. “Many times. Where is the mistake?”

“I have confused the extreme with the unusual.” He lit his pipe judiciously.

“I’m sorry,” I said, lighting my own cigarette. “I don’t follow.” The night was dreary outside, and we had nothing by the way of a case, which often sent Holmes into a black humour during which he would be foul company. But he seemed reflective tonight, though not without an air of dark cynicism. I settled in for a long explanation.

“I thought the murders extraordinary,” Holmes said. “As such, I looked initially for one man. Even after I started to collect evidence that not all of the murder methods matched up, my theories all presupposed a severely limited number of killers. Two men, working in tandem, or one imitating another.”

“Of course you did!” I exclaimed. “How could you not? The brutality, the macabre trophies, the audacity and sheer malice of the killings. They are extraordinary!”

Holmes breathed out blue smoke and shook his head in despair. “Extraordinary only in the sense that it took this long for such a thing to happen. In a city of five million, why should it be surprising that we have created or imported a few bad apples?”

“Bad apples!” I sputtered, outraged. “Holmes, really! Those murders were carried out by a monster of a man, not some wayward child!”

Holmes gave me his thinnest smile. “Ah, but we’ve seen real monsters, dear Watson, haven’t we? The night Somersby died, remember? That warehouse out in Graveshead with the cellar?”

“Of course,” I said. “I shall take that horror to my tomb.”

Holmes wasn’t really listening, but musing as if to himself. “When we came out of that darkened hole, out into the clean night air – as clean as London air gets, anyway – suddenly the idea of more than one brutal murderer in London, even an entire room or building of them, all having meetings and conventions and garden parties, comparing knives and methods and body counts… suddenly that idea seemed not impossible, nor even improbable, but a natural outgrowth of London itself. Don’t you see that most of the official force, Lestrade and Gregson included, want – no – need to believe that this is all the work of one perpetrator for the simple reason that they cannot imagine more than one monster capable of this kind of misdeed roaming around London?”

“They haven’t seen the same things we have,” I said quietly, completing the thought. I thought of vampires crawling out of darkened, cold graves, of monsters in the sea, and our pitched battle in near darkness in that Graveshead cellar. “They don’t know about the monsters.”

“Indeed,” Holmes said. “When one has seen a multitude of horrible things, as we have, the idea of someone, some person, crossing that unspoken boundary out of humanity and into unnatural darkness becomes easier to believe. All too easy, in fact. It just means that of the many monsters lurking out in the night, some of them may be human.”

I had no answer to that and Holmes went to bed shortly thereafter. When I got up the next day, I saw that Holmes had been up early and had turned our sitting room into a fog bank of tobacco smoke in his boredom. Fortunately, Mrs Hammond nearly broke the bell pull later that afternoon in order to consult us on the matter of the Averno Spider and Holmes had the work at hand that was always his preferred antidote to any black moods that might come over him.

Next followed a quick succession of cases that culminated in the unexpected events I have laid out elsewhere, such as ‘The Adventure of the Creeping Man’ involving Professor Presbury and his fanciful but tragic usage of a serum from the black-faced langur. In point of fact, we had just returned from Camford the previous evening and had both of us sat up through the night, myself out of habit and nocturnal proclivity, Holmes out of a perverse fascination with the case we had just finished.

“There is danger there, a very real danger to humanity, Watson,” he had murmured as he took a sample of the langur serum that Professor Presbury had used and subjected it to one chemical test after another. He had also gone through his index and had notes about the doctor in Prague, one Löwenstein, of dubious reputation, who had created the strength-giving serum. Of Dorak, Löwenstein’s agent in London, and his mysterious ‘one other customer’, we had little information other than his letter to Presbury and I had no doubt that Holmes intended to head out there as soon as practicable.

When day finally broke and I heard the first stirrings of our good landlady below, I had just reached for the bellpull to request breakfast for us both when I heard the downstairs door fly open and feet come pounding up the stairs.

Holmes almost certainly heard them, too, but continued his experimentation, sitting on a three-legged stool hunched over the small table of laboratory equipment even when the door to our sitting room flew open and a man burst in.

“I’m sorry,” Mrs Hudson’s voice came from behind him. “I was just coming to tell you that you had a visitor when he rushed right past me!”

“It’s quite all right, Mrs Hudson,” I said. She frowned at the man, but withdrew peaceably when I ushered the man into the room.

“You’ve got to help me, Mr Holmes!” the man said as soon as I had the door closed. “The police are after the wrong man, but there’s no telling them that! I need someone with a rational mind, and I believe you are that man and no one else!”

He was a tall man, quite large, with a youngish, smooth face, but dark hair liberally sprinkled with grey that made me revise my knee-jerk estimate of his age several years upward. His face was handsome, with large, almost shaggy eyebrows. But his countenance was now disfigured by an expression of palpable anguish. He was quietly dressed with dark trousers and brown shirt and frock coat. He waved a newspaper with one hand while the other clutched both his bowler hat and a neat and polished Gladstone bag. The act of clutching both bag and hat in the same hand had bent the brim of the hat quite severely. The man seemed to suddenly notice this and dropped the bag, which clinked heavily onto the floor.

This finally got Holmes’s attention. He set his pipette down with a frown and a sigh and turned on the stool. “Your name?”

The man seemed momentarily taken aback, as if he had not expected this question and it somehow toppled all of his plans. Then he mustered himself again. “I thought you might already know. You investigated Presbury, did you not? My name is Jekyll.” He seemed to expect some recognition from us, and now looked a little peevish when he did not get it.

Holmes stood and took the newspaper from the man’s outstretched hand, then went very still as he reviewed it. “Watson, I think we very much need to hear what this man has to say. In fact, I should say that this far surpasses any other concern we might have at the moment.”

I opened my mouth to reply, then looked back to see the headline of the paper that Holmes held up for my inspection: RIPPER STRIKES AGAIN!

“The paper implicates a man named Edward Hyde,” Holmes said to Jekyll. “You and this Mr Hyde are quite close, I take it? He is a patient, perhaps, since you are clearly a doctor?”

“Why do you say that?” the man said, suddenly suspicious.

Holmes glanced up from the paper, a note of irritation coming into his voice. “Come, now! You have come to us because you have heard of my success and methods. Is it really such a surprise to hear them confirmed? Besides, there is no secret to the matter. When I see a man with a black smear of silver nitrate, so often used in the medical profession, on his right hand, it is no great deduction to say that he is a doctor. Though, with the absence of any bulge to suggest a stethoscope, I am inclined to think it unlikely you are part of any practice. But what is your connection to Hyde, pray?”

The stranger opened his mouth to say something and then looked down at his right hand and wiped off the blemish. Finally, after a great internal struggle he blew out a deep breath and the action seemed to deflate him entirely, as if all his conviction had departed him. “No, Hyde is not a patient.” He collapsed into an armchair and had to clear his throat several times before going on. “Yes, I am a doctor, but not a medical one and I have no practice. I use the silver nitrate in my chemical laboratory. This is really the first time you’ve heard of this affair? I half-expected, from your stories, that you would already know all about it.”

“Watson has taken a few liberties in regards to making his stories more dramatic and romantic than they should be, but he has never, to the best of my recollection, implied that I have made deductions without any data. Watson?” He held out the paper to me. “Perhaps you had best read the article out loud so that we can catch up on events.”

Holmes sat in his own chair and pushed a cigarette case towards our newcomer. “Have a cigarette, Dr Jekyll.”

“No, thank you,” Jekyll said. “I do not indulge in the vice of tobacco. Not for many years now.” His bushy eyebrows, without any discernible movement, managed to somehow portray an impression of prudish, unspoken disapproval.

Holmes lifted his own eyebrows in surprise. “As you wish. There is brandy, if you would care for it.”

“No, thank you,” Dr Jekyll said primly. “I do not take spirits, either, I’m afraid. But perhaps a glass of water, if you have one available?”

I poured Dr Jekyll a glass from a carafe on the sideboard and returned to the paper, eager to know more, but also dreading the details.

The article ran like this:

Some fifteen years after the many murders attributed to a monster known only as Jack the Ripper, it seems that the same killer has returned. At about midnight last night, a hideous incident occurred in Whitechapel that is likely to bring the most infamous name in history back to the lips of every man, woman and child. Miss Eugenie ‘Genie’ Babington, a well-known resident of Whitechapel, was found murdered behind The Hanover public house on Adler Street. She was killed, according to Inspector Stanley Hopkins of Scotland Yard, in the same manner as Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, and so many other women. Her throat had been slit, according to the police, from left to right, with a precise, sharp instrument such as a doctor’s scalpel, which was the known and preferred method that the Ripper used in the previous murders.

The public will, of course, remember that Jack the Ripper was never caught, but it seems likely that this long-standing injustice will, at last, be corrected, for one Franny Barker, a resident of Whitechapel and mother of two, has come forward and identified the man who has committed this atrocity: one Edward Hyde, a man known to the police to be of violent temper and low character. The police of Scotland Yard and the City of London Police are forming a joint task force for the purpose of tracking this murderer down and making certain that he pays the ultimate penalty in the eyes of the law.

Mr Edward Hyde is wanted by the police and anyone who sees him is urged to contact Scotland Yard. Mr Hyde is said to be short but powerfully built, with a great mane of black hair and visage that, to quote Franny Barker’s deposition, ‘only a mother could love, and her just barely!’ He was last seen wearing a black suit, top hat and gentleman’s opera cape.

Holmes gave a low whistle. “Perhaps you should explain your connection to this affair and the precise nature of your relationship to Mr Edward Hyde. I should warn you that with a witness to the murder, things look very dark for him indeed.”

Jekyll, having sat for the briefest of moments, now rose to his feet again, pacing restlessly and looking from one of us to the other, his smooth face wrinkled in confusion. “You really don’t know? I am the other recipient of Löwenstein’s serum, through his agent, Dorak.”

“Well,” Holmes said, lifting his eyebrows in surprise. “That is interesting. But that really does not go very far in explaining your connection to Mr Hyde and this abominable murder, of which you claim that Mr Hyde is innocent.”

“I do claim that, yes,” Jekyll said slowly. He moved in a distracted manner, then finally sank back down into his chair again, then looked keenly at Holmes. “Would you take the case? I must know your answer before proceeding, as the explanation is of the most sensitive nature.”

Holmes’s grey eyes took on that distracted, introspective look that signalled his utmost attention. “If your friend, Mr Edward Hyde, is indeed innocent, then every effort shall be made to prove his innocence and track down the real killer. In fact, such would be true regardless of your appearance here. I am surprised, in fact, that Scotland Yard is not already here to try to enlist our aid in this matter, although that may indicate that new information has come to light, or that they already have the person they believe to be the true killer in their custody.”

“No,” Jekyll said. “I can assure you that Hyde is not yet in their custody. Are they likely to come here?”

“Very likely,” I assured him. “Holmes is ever their first call should they find themselves out of their depth on a case.”

“Which, I daresay, is often,” Holmes remarked dryly. “Come, Dr Jekyll, lay the facts of the case and any evidence of Edward Hyde’s innocence before us. We may not have long before we are interrupted.”

Jekyll’s face smoothed, as if he had just this moment decided which path to take. “Very well. To explain the connection between Mr Hyde and myself I must first explain the nature of my work. It is the langur serum, you see, that is the key. I did have a previous ingredient that was even more effective, but alas that source has long dried up. For years I sought a replacement and have only just the past few months discovered that Löwenstein’s langur serum performs that duty admirably.” While speaking, he took off his frock coat and laid it carefully over the back of the chair. He then proceeded to unbutton his waistcoat and collar and these, too, he laid aside.

“Brand new shirt, but no help for it, I suppose,” he muttered. Then he began to pull off his boots.

“Come, man!” I said. “This is a long way, I assure you, from the Turkish bath. What on earth can you possibly be about?” I would have gone on, but Holmes laughed out loud and waved me back to my chair, thoroughly entertained by the unusual proceedings.

Jekyll reached down for the bag he’d dropped, all but forgotten until now, and began to remove, much to my surprise, a pair of heavy leg irons and manacles such as they might have used in Scotland Yard. I became aware, as he did so, of a distinctly earthy odour about the man, a dangerous whiff of something animal that was not at all what I expected from a well-respected doctor.

He started with the air of a lecturer, but there was a brittle tension about him as he did so, as if he was talking to distract himself from something unpleasant. “The aim of my research, at first, was to isolate and separate the better and more deplorable aspects of human nature.” Boots removed, he laid out the leg irons at his own feet and smiled thinly. “To separate the angel and the devil within our own selves, if you will. At first, this is what I thought I had accomplished.” He carefully threaded the hand manacles through the ring of the leg irons so that they should be interconnected and then started to fit the manacles to his own ankles.

Holmes and I exchanged a look and I could feel my own eyebrows rise in astonishment that was plainly mirrored on Holmes’s own face. I remembered Lestrade talking of a magician that had shocked Scotland Yard with a demonstration in which he freed himself from the restraints commonly used in their prisons. Houdin… or… Houdini, that had been the man’s name. I wondered if we were about to get a similar, private demonstration of the same skills here in Baker Street. Under different circumstances, I would have strongly objected to such a farcical display happening in my very own sitting room, especially with such an urgent case on our hands, but Holmes’s grey eyes sparkled with interest and he leaned forward, so I held my peace.

Jekyll was screwing the bracket of the leg irons around his ankles carefully and precisely, and according to some private measurement, though I noticed that they were actually absurdly loose. It was not likely to be a very impressive demonstration after all, it seemed.

“It took me some years,” Jekyll went on, “to realize that I was quite wrong to think of my research in terms of good and evil. These are too abstract to be so neatly pinned on the careful scalpel of science. It was the highest level of hubris and naivete to think I could accomplish so unscientific a goal. Better to say that I had managed to separate not good from evil, but man from beast. Many academics would consider us separate already, but this is another unscientific theory and quite incorrect. I choose the word beast carefully, scientifically, and do not intend it as a slight. Quite the contrary. It may surprise you gentlemen, and go much against the grain of our London society’s sensibilities, to hear me say that the beast is disdained only by those that do not understand its nature. The beast is dangerous, yes, violent, sometimes, but it is never cruel for cruelty’s sake.”

That was an interesting expression, I thought, and not the first time I had heard it. Mina Dracula had said the very same thing about her husband.

“Having discovered and refined the potion that brought Edward Hyde into existence,” Jekyll went on, “I have come, slowly, to feel myself somewhat responsible for his fate. This is in addition to the irrefutable fact that our fates are quite linked but I promise you that this fact is not what drives me. If I thought now, as I did before, that Hyde was an evil that I had unleashed upon the world, I would gladly end my own life in order to rid the world of it.” He finished with the leg irons, still so loosely fixed that he could likely pull his unbooted feet through without too much effort, and started the somewhat awkward process of moving the turn key so that he could fasten the manacles to his own wrists.

“In my defence, Mr Holmes, there were several supreme incidents, if you will, that quite coloured my judgment against him until I learned the full truth of them. Two cases in the past, and it is quite important that you should understand that there was never any malice on Hyde’s part in either of them. The first was when one of the new motor cars backfired, panicking Hyde, and he ran, in stark terror, away from the sudden noise and trampled a young girl in his haste. She was injured, but not severely; still it was quite traumatic for all concerned. Hyde does share some blame for this terrible incident, but only to the same degree that a carriage horse, running wild from a fire, might. The second was the accidental death of Sir Danvers Carew, MP, though Utterson, a close confidant of mine and the chief witness, had that all wrong, too. I say accidental, though I have no doubt that the police instantly saw Utterson’s point of view and the official report will list the death as deliberate murder. But nothing, gentlemen, could be further from the truth. Hyde never laid a hand on him, merely rounded a corner and so shocked Carew that the man tried to flee into traffic. He was run over by a delivery truck and killed instantly. Utterson claims that Hyde pushed him deliberately into traffic, but this is simply not true.” He finished with the manacles, though, again, I could see that they were set so loosely that they could fall right off.

“It was not really Utterson’s fault, however. You see, Hyde’s ferocious and, frankly, hideous appearance, which you shall shortly make the acquaintance of, makes him seem like a monster out of our worst nightmares. This causes those around him to have a natural, but spurious, reaction to the man, which goes a very long way toward explaining the terrible reputation that follows him around.”

During the utterance of this extraordinary and somewhat cryptic statement, Holmes had leaned forward and locked his hooded gaze on Doctor Jekyll as our new acquaintance tested the foolishly loose fit of his bonds yet again, then finally tossed the turnkey in my direction with a rattle of his chains.

Despite my surprise, I managed to catch it and held it up questioningly.

“You’ll need that,” Jekyll said, “in order to release him.”

“Release who?” I said, wondering if the doctor had started to exhibit some sort of mental breakdown. Did he mean to refer to himself in the third person?

“I regret this demonstration, gentlemen, but I fear that no other will suffice. Not only do you need incontrovertible proof of the connection of which I speak, but you will also need to interview the subject himself in order to prove his innocence, and he would not willingly come here for questioning. However, he is likely to panic, coming to in chains. This set, however, is much stronger than the last set, at least. They will probably hold. Now that I think of it, I wish I’d brought the really heavy set. Ah well, no help for it, I suppose.” He picked up his jacket and riffled through the pocket, removing a small box, which he opened. He pulled out a vial containing a brown, viscous liquid.

“I’m sorry, gentlemen,” Jekyll said, “but I have no other choice. Watch yourselves. He is likely to be very angry.”

So saying, he drank.

Chapter 02

HYDE’S STORY

Dr Jekyll drained the vial in one long draught and then immediately began to spasm and dropped the vial on the carpet, where it cracked and lay still. Jekyll followed it to the floor, falling on his hands and knees, and he gave a long, preternaturally loud and painful groan that seemed to be dredged up from the very bowels of the earth.

Holmes and I had both jumped to our feet with this startling reaction. But what happened next was even more astonishing.

Beneath the doctor’s thin shirt, the skin began to move, to twitch and bubble and roil like an overheated cauldron. I had, since my exposure to the world of vampires, seen horrible things, the fuel of nightmares, but this sudden spectacle made my blood, such as it was, run cold.

The noises coming from Dr Jekyll grew even louder, more agonized, more animalistic, while his torso expanded. I watched in horror as his hands grew to twice their size and sprouted long nails. They flexed once in a powerful grip around the chains and I now understood Dr Jekyll’s careful measurements that had seemed far too loose. The shirt tore clean in half with the expansion of that broad, hunched back.

“Curious,” Holmes murmured, tilting his head and stepping slightly closer to get a better viewpoint. “A conservation of mass, I see, so science has not wholly left us. More powerful body… almost like a chimpanzee’s, though I would hazard a sovereign or more that the weight is the same. Almost certainly stronger.”

“Holmes,” I said, “don’t get too close!”

When the doctor looked up, I took an involuntary step backwards, so monstrous was his face, with a protruding lower jaw and large mouth filled with teeth. His hair was a wild mane of deepest black now, with bushy facial hair that on another man would have been called mutton chops, a continuation of the black mane. The eyes had gone a deep amber, bestial, and his brow bore dark, shaggy eyebrows. While he was still a man, there was also much of the night creature about him, features that reminded me in turn of the lion, the wolf and the ape. There was an even stronger animalistic odour that emanated off him now. This newly transformed man presented the darkest, most corrupt imitation of humanity to my eyes, a display of the most atavistic and dangerous nature that man had to offer. There remained no trace whatsoever of the handsome, smooth-faced, statuesque Dr Jekyll that had been in our sitting room moments before.

This new man shook the chains on his arms, clearly alarmed, and he jumped to his feet in obvious panic. He spun, moving with alarming speed, and yanked so that his powerful muscles bulged; the metal groaned, but held. The hands were broad, blunt, with long, unkempt fingernails and I shuddered to think of the damage those hands could do as he flexed them.

“Holmes!” I said, for he was still standing less than five feet from the monster. But Holmes ignored me.

“Mr Edward Hyde, I assume?” Holmes said mildly. He slapped the paper in his hand. “If the newspaper’s somewhat garbled and pithy description is accurate?”