7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

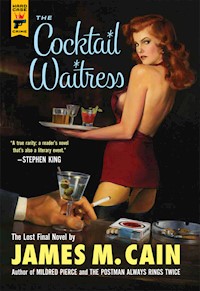

- Herausgeber: Hard Case Crime

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Following her husband's death in a suspicious car accident, beautiful young widow Joan Medford is forced to take a job serving drinks in a cocktail lounge to make ends meet and to have a chance of regaining custody of her young son. At the job she encounters two men who take an interest in her, a handsome young schemer who makes her blood race and a wealthy but unwell older man who rewards her for her attentions with a $50,000 tip and an unconventional offer of marriage... Includes a 4,000 word feature on the locating of this "lost" Cain novel, by Hard Case Crime editor, Charles Ardai

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

SOME OTHER HARD CASE CRIME BOOKS YOU WILL ENJOY:

FIFTY-TO-ONE by Charles Ardai

KILLING CASTRO by Lawrence Block

THE DEAD MAN’S BROTHER by Roger Zelazny

THE CUTIE by Donald E. Westlake

HOUSE DICK by E. Howard Hunt

CASINO MOON by Peter Blauner

FAKE I.D. by Jason Starr

PASSPORT TO PERIL by Robert B. Parker

STOP THIS MAN! by Peter Rabe

LOSERS LIVE LONGER by Russell Atwood

HONEY IN HIS MOUTH by Lester Dent

QUARRY IN THE MIDDLE by Max Allan Collins

THE CORPSE WORE PASTIES by Jonny Porkpie

THE VALLEY OF FEAR by A.C. Doyle

MEMORY by Donald E. Westlake

NOBODY’S ANGEL by Jack Clark

MURDER IS MY BUSINESS by Brett Halliday

GETTING OFF by Lawrence Block

QUARRY’S EX by Max Allan Collins

THE CONSUMMATA by Mickey Spillane and Max Allan Collins

CHOKE HOLD by Christa Faust

THE COMEDY IS FINISHED by Donald E. Westlake

BLOOD ON THE MINK by Robert Silverberg

FALSE NEGATIVE by Joseph Koenig

THE TWENTY-YEAR DEATH by Ariel S. Winter

The COCKTAIL Waitress

by James M. Cain

A HARD CASE CRIME BOOK

(HCC-109)

First Hard Case Crime edition: September 2012

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street

London

SE1 OUP

in collaboration with Winterfall LLC

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2012 by the Estate of James M. Cain

Cover painting copyright © 2012 by Michael Koelsch

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

Print edition ISBN 978-1-78116-032-9

E-book ISBN 978-1-78116-035-0

Design direction by Max Phillips

www.maxphillips.net

Typeset by Swordsmith Productions

The name “Hard Case Crime” and the Hard Case Crime logo are trademarks of Winterfall LLC. Hard Case Crime books are selected and edited by Charles Ardai.

Printed in the United States of America

Visit us on the web at www.HardCaseCrime.com

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

Afterword

The COCKTAILWaitress

1

I first met Tom Barclay at my husband’s funeral, as he recalled to me later, though he made so little impression on me at the time that I had no recollection of ever having seen him before. Mr. Garrick, the undertaker, was in the habit of calling Student Aid, at the university, for boys to help him out, but one of those chosen that day, a junior named Dan Lacey, couldn’t come for some reason, and his father asked Tom as a favor to go in his place. Tom, though he’d graduated the year before, did the honors with me, calling for me and bringing me home in a big shiny limousine. But he rode up front with the driver, so we barely exchanged five words, and I didn’t even see what he looked like. Later, he admitted he saw what I looked like—not my face, as I was wearing a veil, but my “beautiful legs,” as he called them. If I paid no attention to him, I had other things on my mind: the shock of what had happened to Ron, the tension of facing police, and the sudden, unexpected glimpse of my sister-in-law’s scheme to steal my little boy. Ethel is Ron’s sister, and I know quite well it’s tragic that as a result of surgery she can never have a child of her own. I hope I allow for that. Still and all, it was a jolt to realize that she meant to keep my Tad. I knew she loved him, of course, when I went along with her suggestion, as we might call it, that she take him until I could ‘readjust’ and get back on my feet. But that she might love him too much, that she might want him permanently, was something I hadn’t even dreamed of.

I caught on soon enough, though, when she came over, at graveside. Leaving Jack Lucas, her husband, and Mr. and Mrs. Medford, her parents, who of course were also Ron’s parents, she first shook hands with Dr. Weeks, and I suppose thanked him for the beautiful service he’d conducted, and then came over to me. “Well, Joan,” she began, “you got what you wanted at last—I hope you’re satisfied.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” I asked her.

“I think you know.”

“If I did I wouldn’t be asking. Say it.”

“Well the police certainly thought it funny, as everyone else did— you putting him out in the rain, in nothing but his pajamas, so he had to drive somewhere to get taken in, and if he crashed on a culvert wall I don’t think you were really surprised—or much upset.”

“I put him out,” I told her, “after he came home drunk at two o’clock Sunday morning, woke me hollering for another beer, and then got the bright idea of punishing Tad for something he did week before last—and Tad still healing from the last time. I knew nothing about the car he had borrowed over the weekend, which must have been at the curb, keys still in the ignition, for him to be able to drive off the way he did. Nor did I pay much attention when I looked out and found him gone. By that time, nothing he did or could do would surprise me, and as soon as I got Tad quiet I went to bed. It wasn’t until the afternoon, when he was finally identified, that I found out what had happened to him. So if you think I planned it that way, you’re mistaken.”

“So you say.”

“And so you’ll say too.”

“… I beg your pardon, Joan?”

“Say it, Ethel, what I told you to say, that you’re mistaken—or I’m slapping your face right here, in front of Dr. Weeks, in front of the Medfords, in front of Ron’s friends, in a way you won’t forget. Ethel—”

“I was mistaken.”

“I thought you were.”

“I said it. I don’t think it.”

“What you think means less than nothing to me. What you say does, and it better correspond.” We stood there glaring at each other, but then ice water began to drip down my back. It crossed my mind, suppose she really gets mean, and tells me to come get Tad? I thought: I can’t take him yet, as I can’t work if I have to stay with him, and I had to get work to eat, and also pay for him, as of course I couldn’t just sponge his keep off Ethel. I felt myself swallowing, then swallowing again, and at last swallowing hard. I said: “Ethel, I apologize for my tone. I’ve been through quite a lot, and being accused of murder, or something that sounds a lot like it, is more than I can take. So—”

“It’s O.K. I make allowance.”

“Now, may we get on?”

“If you’re talking about Tad, everything’s taken care of, and there’s nothing to get on to.”

“Then, I thank you.”

But I sounded stiff, and she snapped: “Joan, there’s nothing to thank me for, Tad’s my own flesh and blood. He’s welcome and more than welcome, for as long as may be desired. And the longer that is, the better I’m going to like it.”

That’s when she overshot it, not so much by what she said, as by the look in her eye as she said it. And that’s when I woke up, to the fact it was not at all like her to take things lying down, especially an insult from me, and if she did take it, there had to be a reason. It brought me up short, but what could I do about it, especially here by the side of Ron’s grave, with his father, mother, and friends still whispering nice things about him? There was nothing that I could think of, as slaps wouldn’t cover it, or make any sense at all—they never made sense actually, as I had often found out to my sorrow, and would shortly find out again. All I could do was blink, and I heard myself ask, very meekly: “Where is Tad, by the way?”

“Joan, I thought best not to have a three-year-old child at the service, but he’s in good hands and there’s no need for you to worry.”

What made me turn I don’t know—she may have glanced over my shoulder—but anyway, I did, and there not far away was my son, playing beside Ethel’s car, still favoring his left arm when picking up his ball, while Eliza, the woman who did Ethel’s cleaning, looked on. I started for him, remembered, and lifted my veil, throwing it up on my hat. About that time he saw me, and came running, but in the way a three-year-old runs, leaning over forward, his feet having a hard time keeping up with his head. They didn’t quite, but as he toppled I caught him. He wailed at the touch of my hand against his shoulder. I moved my hand and held him close and kissed him and loved him. When we’d had our beautiful moment Eliza assured me: “He’s been like a lamb, Miss Joan—no trouble at all. I was so sorry, what happened to Mr. Ron.”

“Thanks Eliza, that helps.”

“Want me to take him now?”

“Please.”

When I got back, Ethel had rejoined her parents and Jack. I thanked Dr. Weeks, shook hands with Ron’s friends, men he knew from the bars mostly, a none-too-refined bunch in work pants and windbreakers, but very well-behaved. Then I nodded to Mr. and Mrs. Medford, who nodded in return, coldly, and it was easy to see they believed Ethel’s nonsense. Then I rejoined Tom, who had withdrawn a few feet when Ethel came to me. “Are we ready?” I asked him.

“Any time you are, Mrs. Medford.”

And so, on an afternoon in spring, I left the cemetery in College Park, Maryland, and headed for my home in Hyattsville, some five miles down the line, a suburb of Washington, D.C., to face the rest of my life, with a living to make, for myself and my little son, and no idea at all how to do it. So who am I, and why am I telling this? My maiden name is Joan Woods, and I was born in Washington, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Pittsburgh. My father, Charles Woods, is a lawyer and a community leader, with only one fault that I know of: He does what my mother says, always. At seventeen, I entered the University of Pittsburgh, but then opportunity knocked at my door: a boy from a steel family fell in love with me, and presently asked me to marry him. My mother was quite excited, and my father yessed her completely. But Fred bored me to tears, and a situation developed. To give it a chance to clear up, I took myself off to Washington, where a girl I knew had a job on “the Hill,” as it’s called. She thought she could work me in too, and after taking me into her apartment, had me “stand by” for her call. Actually, it was “sit by,” all day long, which can get tiresome, I found, as well as murderously lonesome. When the boy down the hall knocked I let him in, and one thing led to another. Next time, I was pregnant. But I knew nothing at all of anything that could be done. So far as I was concerned, a pregnant girl got married, which I did. To call Ron a reluctant bridegroom would be the understatement of the year. He hated getting married, hated little Tad, and I think hated me.

My mother hated me, and my father cut me off. I was left at the mercy of the Medfords, who I think hated me too, just to make it unanimous. Mr. Medford gave Ron a job, as a salesman in his real estate firm, and Ron did quite well—except he kept getting drunk. Then Mr. Medford would fire him, but hire him on again the following week. He fired and rehired him so often that Ron began gagging about it, calling himself Finnegan Medford, though that ended for good when Ron ruined the sale to the Castles, turning up drunk the way he did and putting his hands on Mrs. Castle, accidentally he claimed. There was no hiring him again after that, and Ron spent the months that followed cursing his father’s name, and my name, and our son’s, but not earning any income, so that our savings ran out and the utility companies wouldn’t hear excuses anymore and turned off service at our house.

The house—Mr. Medford also gave us that, or half gave it to us, leaving a $7,500 mortgage dangling, as an “incentive” to Ron, he said, to straighten himself up and accept responsibility. It had no such effect, but it did make me gray in my teens, finding $110 each month for the amortization payments, back when there was still money to be found. Now there was none, and the foreclosure warnings had begun to arrive by mail.

It was in front of this house, a bungalow from the 1920s, that we stopped that day of the funeral, with Tom jumping out, handing me down, and waiting on the sidewalk while I ran up on the porch, found my key, and unlocked the front door. Then I turned, waved, and (he insisted later) blew him a kiss (which I don’t believe), having no idea at all that at that moment I was looking straight at my job, in a restaurant down the hill, and at the man I would come to crave as I crave life itself.

So what’s the fly in the ointment, and why am I taping this? It’s in the hope of getting it printed to clear my name of the slanders against me, in connection with the job and the marriage it led to and all that came after—always the same charge, the one Ethel flung at me of being a femme fatale who knew ways of killing a husband so slick they couldn’t be proved. Unfortunately, they can’t be disproved either, at least in a court of law, for as long as the papers say “it is alleged,” you can’t sue anyone. All I know to do is tell it and tell it all, including some things no woman would willingly tell. I don’t look forward to it, but if that’s how it has to be, it’s how it has to be.

Whatever I did, Tom blew me a kiss, and drove off.

2

I had put on the veil, not from old-fashioned ideas about what a widow should wear, but to hide the side of my chin, which was black and blue from the bruises Ron had put on it, by hitting me that night, while we wrestled for Tad. I could have covered them with makeup, but knew the Medfords, to whom I couldn’t explain the reason, would disapprove, and the veil was a simple way out. So now I opened my jar of Max Factor and went to work. But first of all I undressed, taking off the dark suit, pantyhose, black bra, and dress shoes I had on, then working in front of the mirror, there at my dressing table. And as to what I looked like naked: This was thirteen months ago, and I was just twenty-one. I’m just under medium in height, normally a bit on the slender side, and heavy-busted, as they say. But my legs are my best point, as I’ve been told often enough. They are straight, round, soft, and gracefully formed. My face is thick and my features stubby, but shadows under my eyes do something for me, so I’m not too bad-looking. My hair is blonde, but dark blonde, “corn-husk blonde,” some call it, with the gray streaks I’ve already mentioned. My eyes are green and a bit large, so with the shadows I do have a cat look, that I have to admit.

I put the makeup on, then powdered and used my rabbit’s foot, finally coming up with a reasonably decent face. Then I dressed, putting on white bra, white panties, red socklets, flat shoes, Levis, and a rough blouse, as being suited to the work I had in mind, of which more in a moment. I had just finished when I heard the front doorbell. It didn’t ring, as my current was cut off for non-payment of bills, but it clicked, and then there came a knock. I went down the hall and opened, expecting some bill collector, and rehearsing something to say. But the same two men were there as I’d talked to before, down at the county building, police officers. “Sergeant Young, Private Church, come in,” I told them.

“You remember us, then?” said the older of the two men, the sergeant, taking the cap of his uniform into his hands as he came inside.

“Well, I wouldn’t forget you so soon.”

“I mean, our names.”

“I have them right, haven’t I?”

“Yes, but it’s unusual.”

By that time, I’d brought them into the living room, that I wasn’t any too proud of, as the sofa had had one of its legs pulled off, on one of Ron’s lively nights, and the broken corner was held up by a pile of books. However, I seated them with their backs to it, sat down myself, and asked: “So? What can I do for you gentlemen?”

“Tell her,” the sergeant told Church. The younger officer eyed him with what I thought was a little reluctance, but finally turned back to face me.

“We’re off duty, Mrs. Medford,” said Church, “but you were so cooperative before, when we questioned you on what happened, that we stopped by this time to tell you, ’stead of asking you, something you ought to know—that we think you ought to know. And why we’re free to tell is, the woman who called last night didn’t give her name, so she can’t claim confidentiality—as they’re calling it now. Hey, there’s a word and a half.”

We all laughed and I felt guilty inside, seeing anything funny on this day of days, but then I said: “O.K., Private Church, I’m listening. What did you come to tell me?”

“About this call we got. In reference to a guy, a guy so happens you know, name of Joe Pennington.”

“Now I know who called you!”

“As we think we do too.”

“What did she say about Joe?”

“That he was here, that he was with you Saturday night, at the time your husband came home. That instead of your little boy, he was the cause of the fight, and helped you do it, push your husband out on the porch, that—”

“I haven’t seen him in over a year!”

“As we found out, Mrs. Medford.”

“Why it’s all a silly lie!”

“We know that, Mrs. Medford—we checked Joe Pennington out, he was doing the Block that night, the Block over in Baltimore, as he had a witness to prove, a very pretty witness, who really went into detail—”

“What we came about,” the sergeant interrupted to say: “Why would this woman tell it, such a made-out-of-the-whole-cloth tale? Well, after we checked out Joe, we think we came up with the answer, and as it kind of concerns you, we thought we’d stop by and tell you. She kept talking, this woman who called, about your sister-in-law, who had taken in your little boy, for a reason she said over and over—”

“‘Out of the goodness of her heart.’”

“That’s what she said, we expected you to know, as it sounded like kind of a habit, something she said pretty often. And the thought crossed our mind that the woman who called us up and the kind sister-in-law were one and the same woman. So, where do you come in, and what was the point of Joe? You wouldn’t come in at all, and Joe wouldn’t have any point, unless, unless, unless, she was trying to egg us on, to move against you somehow, to have you declared unfit, an unfit mother that is, of the child she’s now taking care of. In other words, if she could prove that you were immoral, she could keep the child herself—something of that kind, we both thought was in her mind, and that’s what we came to tell you. Now does it tie in, at all?”

“She practically told me so, no more than an hour ago. At my husband’s graveside she stood and all but admitted she wanted my boy for herself. If she loves him, I can’t blame her for that—I do, and everyone does, and she’s had a blow, a terrible tragic blow. And she can’t have a child anymore of her own, and no doubt it’s affected her mind. But—”

I couldn’t go on, and sat there, trying to regain control. “It’s what we came to tell you,” said Sergeant Young, very gently. “We thought you ought to know.”

I still sat there, but caught his eye running over my clothes. “I’m dressed for work,” I explained. “I have to get started today.”

“… What kind of work do you do?”

I hated to answer, but felt I had to say something. “Well, as of today,” I said, “I hope to do some. There’s a power mower out there, under the back porch, and a can of gasoline, and up the street a ways, at houses where I’m not known, are lawns that haven’t been cut yet, and I thought I could do a couple, that is if the people will let me—it would bring in a few dollars, and with that I’d buy something to eat and then take a day to think. If I could gain a little time, I might get a job at Woodies, or Hecht’s, or Murphy’s—I mean as a salesperson. I’m not trained for any special work—in high school I took English composition, and in college had barely got started before I withdrew—and then how’d you guess it, got married. Then my little boy came, and—that’s where I’m at, now.”

Why I talked so much I don’t know, but they seemed so concerned I wanted to. And I was nervous, too, I suppose; anyone would be, talking to the police.

After a moment the sergeant asked: “Had you thought of restaurant work?”

“How do you mean, restaurant work?”

“Like waiting on tables.”

A look must have crossed my face, as he went on, very hurriedly, and a little embarrassed: “O.K., O.K., O.K.—just asking, no offense intended. There’s one thing about it, though: Compensation is mainly in tips, and them you bring home every night. You don’t wait till Saturday—or the first of the month, as some jobs make you do.”

“… Keep talking, please,” I said.

“Well, another thing is, that the Garden of Roses down here is just down the street from you. For Woodies you’d need a car, as you would for the Hecht Company, or Murphy’s, or any place at the Plaza. And Mrs. Rossi might need someone. She often does—and you could refer to me.”

“Who’s Mrs. Rossi?”

“Bianca Rossi, the owner. Her husband, who died, was Italian, but she’s not. And, she’s O.K. Kind of a sulky type, but decent and not at all mean.”

“… She sounds like my girl.”

“You being good at names would help, specially on tips.”

“My mother,” I explained, “went to private school, where they specialized in manners, especially the importance of names, and she drilled it into me. They didn’t think to tell her that the essence of manners is kindness.”

“We could ride you down.”

“If you’ll wait till I put something on.”

“What you have on is fine—you look like a working girl, and a working girl is what’s wanted—that is, if anyone is. If Bianca takes you on, she’ll give you a uniform.”

“Then what are we waiting for?”

It was that quick and that unexpected, the most important decision of my life. Until then, I’d never thought of waiting on tables—and I didn’t have time to question if I was too proud to take tips, or to think about it at all. The main thing was: It meant money, quick. So in ten seconds there we were rolling, in Sergeant Young’s car, down the hill to the restaurant.

3

The Garden of Roses is on Upshur Street in Hyattsville, across from the County Building, which is on Highway No. 1 at the south of town, “The Boulevard,” as it’s called. It’s one story, of brick painted white, and with its parking lot sprawls half a block. It’s in two wings, with a center section connecting: one wing the restaurant, the other the cocktail bar. The center section is half reception foyer, really a vestibule as you go in, with a hatcheck booth facing, a half-door in its middle. Sergeant Young handed me down and walked me to the front door while Private Church waited in the car.

“This is very kind of you, helping me when you didn’t need to and had no reason—”

“I didn’t need to, but I had reason.”

I caught his eye running over my clothes once more, and I thought perhaps over what was beneath my clothes as well, and I stiffened slightly, which he must have seen because when he next spoke it was with a greater formality. “Mrs. Medford, I have an idea what you have been through. I saw the records from when you brought your son to the hospital to have his arm seen to. I can see the marks on you, and in your home. If you’ll forgive me saying so on the day you buried him, your husband was a brute, and you’re well rid of him— provided that it doesn’t cost you your child as well.”

I nodded my thanks. We stood a moment longer, and it appeared to me that Sergeant Young would have wanted to say more, but not with his partner looking on. He returned my nod and walked back to his car.

When he and Private Church had driven off I went inside to the foyer. No light was on and for a moment, after the sun, I couldn’t see. But then a girl, a waitress, popped out of the dining room, and said: “We’re closed till five o’clock—try the Abbey at College Park.”

“I’m calling on Mrs. Rossi.”

“What about?”

“That I’ll tell her, if you don’t mind.”

“I got to know what you want with her.”

Now my temper, as perhaps you’ve guessed, is one of my life problems, and I stood there for a moment or two, trying to get myself under control, when suddenly a woman was there, middle-aged, no taller than I was, but big and thick and blocky. The girl said: “Mrs. Rossi, this girl wants to talk to you, but won’t say what about. I tried to get out of her what she wants of you but she won’t—”

“Sue!”

Mrs. Rossi’s voice was sharp and Sue cut off pretty quick. “… Sue, curiosity killed the cat, and what’s it to you what she wants of me?”

Sue vanished, and Mrs. Rossi turned to me. “What do you want of me?” she asked.

“Job,” I told her.

“… What kind of job?”

“Waiting on table.”

She studied me, then said: “I need a girl, but I’m afraid you won’t do—I don’t take inexperienced help.”

“… Well—since I’ve barely said three words, I don’t see how you know if I’m inexperienced or not.”

“The three words you said, ‘Waiting on table,’ were enough. If you’d ever done this kind of work, you’d have said ‘on the floor.’ …Are you experienced or not?”

“No, I’m not, but—”

“Then, I don’t take inexperienced help. Have you had lunch?”

“… I wasn’t hungry for lunch.”

“Breakfast?”

“Mrs. Rossi, you make me want to cry—I’ll tell Sergeant Young, who suggested I come to you, that at least you have a heart.”

“… You know Sergeant Young?”

“I do. I think I can call him a friend.”

“And he sent you to me?”

“He said you might need someone.”

“What made him think I could use you?”

Well, what had made him think she could use me? I tried to think of something, and suddenly remembered. I told her: “He was struck by my sureness on names. He thought in this work it might help.”

“What’s my name?”

“Mrs. Rossi, Mrs. Bianca Rossi.”

“What’s the girl’s name that was here?”

“Sue.”

She put a hand in the dining room, snapped her fingers, and when Sue reappeared asked me: “What’s your name?”

I started to say, “Mrs. Medford,” but caught myself and said: “Joan. Joan Medford.”

“Miss or Mrs.?”

“I’m a widow, Mrs. Rossi. Mrs.”

Then to Sue: “This is Joan, and she’s coming to work on the floor. Take her back, give her a locker, find a uniform for her—from the back-from-the-laundry pile, there on the pantry shelf.” And then to me: “When you’re dressed, come back to me here and I’ll tell you what you do next.”

“Yes, Mrs. Rossi. And thanks.”

“Something about you doesn’t quite match up.”

“It will, give me time.”

Sue led through the dining room to a kitchen with a chef and two cooks in it, chopping and slicing and stirring, to a corridor that led to a room with lockers on one side and benches down the middle. She opened the locker with a key she took from a rack, then disappeared, and by the time I’d taken my things off was back with my uniform, the short skirt and apron in one hand, the jersey in the other. She watched while I hung up my clothes in the locker, and put on the things she had brought me. The key had a wrist loop on it, and when I had locked up and slipped it on, I must have made a face at my legs, which of course were bare, as she said: “It’s O.K.—some of the girls don’t wear any pantyhose. On some things, like fingernails, Bianca’s strict as all get-out, but on others she don’t care.”

She led on back to Mrs. Rossi, who was still in the dining room. But with her was a gray-haired, rather good-looking woman perhaps in her forties, in peasant blouse, crimson trunks, and beige pantyhose that set off a pair of striking-looking legs. “Be with you in a minute,” Bianca told me, and went on talking. But the woman asked: “Hey wait a minute—who is she?”

“New girl,” said Bianca. “But about the imported bubbly—”

“Wait a minute, wait a minute! Why’s she dressed for the dining room?”

“It’s where she’s going to work.”

“Oh no she’s not. Here you’ve been promising me a girl, and now when she’s here you put her to work on this side.”

“She’s new, she’s never been broken in, she can’t work in the bar, she’s not qualified.”

“Oh yes she is!” And then, to me: “Show her your qualifications, to work in the cocktail bar. The gams, I’m talking about.”

I turned to show my bare legs, and she went on: “And, by her looks she’s been broken in.” Then to me again: “Haven’t you?”

“If you mean what I think you mean,” I admitted, “yes. I’m a widow, so happens. A recent widow with one child.”

“So, Bianca?”

It wasn’t the first time, and wouldn’t be the last, that I’d see her take a position and then reverse herself when pressed. “O.K., take her over.”

“Come on,” said the woman to me, leading me back toward the lockers. “Name, please?”

“Joan. Joan Medford.”

“Liz. Liz Baumgarten.”

I couldn’t help liking Liz, I don’t think anyone could, but suddenly I asked: “When does the cocktail bar close?”

“One o’clock. Why?”

“How I get home is why. The restaurant, I know, closes at nine o’clock, and I could walk home at that hour. But at one in the morning—”

“No problem—I’ll ride you, Joan. I have a car.”

We’d reached the changing room, and Liz closed the door behind her. I took off the skirt, apron, and blouse, and she brought the same trunks as she was wearing, and another peasant blouse. Then, opening a locker, she took out a package of pantyhose. “They’re beige—O.K.?” she asked.

“Oh my—and thanks, Liz.”

“In the bar, bare legs get kind of cold at one o’clock in the morning. But, if you’ll accept a suggestion from me, with what you’ve got to go inside this blouse, I’d leave the bra off.”

“You sure about that?”

“Well, I do. It kind of helps with the tips.”

“With me, tips are the main thing.”

“And with everyone, Joan. Don’t be ashamed.”

And then, explaining: “In case you’ve been wondering, why I would want competition, when I’ve had it all to myself, well, it kind of works backward, there in a cocktail bar. Because, swamped with work, I’ve been slow, and in a bar, it’s one thing you don’t dare to be. They’d wait for food, but drinks to them are important. And when I slow down from being swamped, they get real sore about it. And when they get sore they don’t tip. What I’m trying to say, beyond a certain point, a whole lot of people don’t help, not with the tips they don’t. Vice versa, you could say.” And then, when I’d put on the pantyhose, trunks, and peasant blouse, which drew tight over two points in front: “You’ll do. I’ll say you’re qualified.”

“You’re not bad yourself.”

“O.K. for an old lady—pass in a crowd.”

She was a lot better than that, and as to what she was actually like: I never did guess her age, but whatever it was, it was enough to give her gray hair all the way through—beautiful gray hair, silver almost, that she wore cut at her shoulders, and curled. She was medium in size, with features slightly coarse, I have to say, and yet damned good-looking. Her eyes were a light blue, and wise but not hard. And her legs were different from mine—where mind are round and soft, hers were full of muscle, but with keen lines and a graceful way of stepping.

She led on out again, to the dining room, to the foyer, and to the bar, where a blocky-looking man in a white coat was polishing glasses with a cloth and arranging them in neat rows. “Joan, Jake, Jake, Joan—she’s our new girl, Jake. Go easy, she’s never worked a bar before.” With that, she headed off for the kitchen.

“Haya, Joan.”

“Jake, hello.”

It turned out that on alternate weeks, I was due in at four o’clock instead of five, to fix set-ups for Jake, as well as get the place ready, putting out Fritos in bowls, and setting the chairs down, where they’d been put up so the place could be swept. The sweeping was going on now, by a boy with a push mop, so I got at the set-ups first.

“First set-up is for the old-fashioned. You know what an old-fashioned is?”

“You mean the orange slices and cherries?”

“… Yeah, them.” He gave me a long look, then went on: “And for Martinis?”

“I turn the olives out in a bowl and stick toothpicks in them.”

“For Gibsons—”

“Onions, no toothpicks.”

“O.K. Now, on Manhattans—”

“Cherries.”

“No toothpicks if they have stems on them. But sometimes the wrong kind is delivered, and them without stems take picks. On Margaritas—”

“Salt? In a dish? And a lemon, gashed on one end, to spin the glasses in?”

“Speaking of lemon—”

“Twists? How many?”

“Many as three lemons make. Cut them thick, put them in a bowl, and on top put plenty ice cubes, so they don’t go soft on me. I hate soft twists.” He looked at me like I was a dancing horse or some other marvel. “You sure you never …?”

I explained: “My mother used to give parties, and my father fixed the drinks. I was Papa’s little helper.”

“Christ, you have a father—I should have known. Well, it takes all kinds, don’t it?”

It was the sort of remark I could have taken poorly, but he was smiling as he said it, so I smiled back at him. “What else?”

“The Fritos—they’re for free, and you keep the bowls filled at all times. They put the customers in mind of having a drink.”

“You mean they’re salty.”

“I don’t and you don’t. I mean they’re compliments of Bianca, and you know what’s good for you that’s what you mean, too.”

“They’re special from Mrs. Rossi.”

“And don’t you forget. She’s a nut about it.” He tossed his cloth down on the bar, untied his apron, and came around to my side. “Let me show you the rest.”

He showed me my pocket totalizer, my cash register, and my book of slips, and explained to me how to keep the slips in separate piles, and then when a check was called for, to tote it up on the totalizer, present it to the guest, take his money to the register, put it in and ring up the amount of the check, then take out his change and bring it back to him. “And for Christ’s sake don’t make a mistake,” he growled, looking me in the eye. “Bianca’s easy on some things, like wind blowing free in the blouse, but on others, like clean fingernails and money, she’s a bitch. You make a mistake, it’s on you.”

“I won’t make a mistake.”

I had just got the chairs down and was putting the Fritos out when Liz came back again, from where she’d been in the kitchen. “So let’s split up our stations now,” she said. “How you say we split it right down the middle and alternate: one week I’ll take the near station, the one by the door, while you take the one near the men’s room, next week, vice versa. Fair enough?”

“O.K., suits me fine. But this week you take the station next to the door, so you can greet them when they come in, the patrons I mean—they’ll all be strangers to me.”

“That’s how we’ll do it, sure,” she said. Then:

“Got to go—here comes Mr. Four-Bits, always our first customer. You’d think, the way he rolls out his two quarters, they were solid silver, from the Philadelphia mint.”

I looked, and Mrs. Rossi was bringing a customer in, an important-looking, middle-aged man in gabardine slacks and sport shirt. Liz motioned, and Mrs. Rossi started to seat him at her station. But when he saw me he stopped, stared, and said something. Bianca looked surprised, and brought him over to me. It was my first meeting with Earl K. White, and I was just as startled as Liz.