Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Hard Case Crime

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

The year is 1977, and America is finally getting over the nightmares of Watergate and Vietnam and the national hangover that was the 1960s. But not everyone is ready to let it go. Not aging comedian Koo Davis, friend to generals and presidents and veteran of countless USO tours to buck up American troops in the field. And not the five remaining members of the self-proclaimed People's Revolutionary Army, who've decided that kidnapping Koo Davis would be the perfect way to bring their cause back to life...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 488

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

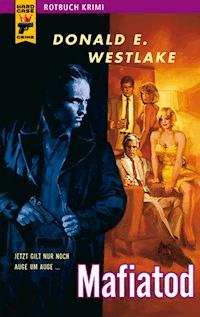

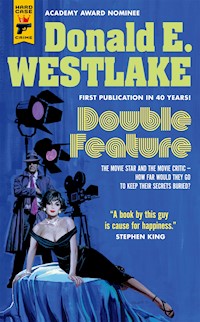

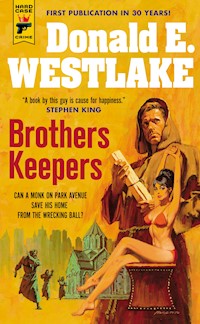

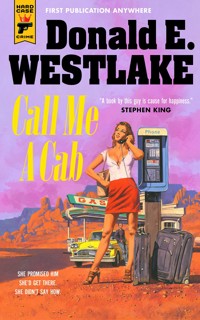

SOME OTHER HARD CASE CRIME BOOKS

YOU WILL ENJOY:

361 by Donald E. Westlake

THE CUTIE by Donald E. Westlake

MEMORY by Donald E. Westlake

SOMEBODY OWES ME MONEY

by Donald E. Westlake

LEMONS NEVER LIE

by Donald E. Westlake writing as Richard Stark

FIFTY-TO-ONE by Charles Ardai

KILLING CASTRO by Lawrence Block

THE DEAD MAN’S BROTHER by Roger Zelazny

HOUSE DICK by E. Howard Hunt

CASINO MOON by Peter Blauner

FAKE I.D. by Jason Starr

PASSPORT TO PERIL by Robert B. Parker

STOP THIS MAN! by Peter Rabe

LOSERS LIVE LONGER by Russell Atwood

HONEY IN HIS MOUTH by Lester Dent

QUARRY IN THE MIDDLE by Max Allan Collins

THE CORPSE WORE PASTIES by Jonny Porkpie

THE VALLEY OF FEAR by A.C. Doyle

NOBODY’S ANGEL by Jack Clark

MURDER IS MY BUSINESS by Brett Halliday

GETTING OFF by Lawrence Block

QUARRY’S EX by Max Allan Collins

THE CONSUMMATA

by Mickey Spillane and Max Allan Collins

CHOKE HOLD by Christa Faust

The COMEDY Is FINISHED

by Donald E. Westlake

A HARD CASE CRIME BOOK

(HCC-105)

First Hard Case Crime edition: February 2012

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street

London

SE1 0UP

in collaboration with Winterfall LLC

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and

incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination

or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual events

or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2012 by the Estate of Donald E. Westlake

Cover painting copyright © 2012 by Gregory Manchess

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

Print Edition ISBN 978-0-85768-408-0

E-book ISBN 978-0-85768-409-7

Design direction by Max Phillips

www.maxphillips.net

Typeset by Swordsmith Productions

The name “Hard Case Crime” and the Hard Case Crime logo

are trademarks of Winterfall LLC. Hard Case Crime books are

selected and edited by Charles Ardai.

Printed in the United States of America

Visit us on the web at www.HardCaseCrime.com

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

Donald Westlake began writing this book in the late 1970s. In the early 1980s, he sent a carbon copy of the finished manuscript to fellow crime writer Max Allan Collins, with whom he’d been corresponding for more than ten years. Shortly afterwards, Don decided not to publish the book, in part because Martin Scorsese had just released the movie The King of Comedy and Don thought some readers might feel the movie’s premise and the book’s were too similar. Max packed the manuscript away in a box in his basement, where it sat for the better part of the next three decades.

When Hard Case Crime published Memory in 2010, describing it as “Donald Westlake’s final unpublished novel,” Max informed us of this one’s existence, unearthed the faded typescript, and sent it to us in the hope that the book would finally see print.

That it has is thanks to Abby Westlake and to Larry Kirshbaum, agent for the Westlake Estate, who agreed to let us publish it—but all three of us owe special thanks to Max Allan Collins, without whom The Comedy Is Finished might never again have seen the light of day.

This is for Brian Garfield, who knows what I’m doing better than I do.

Sometimes people call me an idealist. Well, that is the way I know I am an American. America is the only idealistic nation in the world.

PRESIDENT WOODROW WILSON

SIOUX FALLS, SOUTH DAKOTA

SEPTEMBER 8, 1919

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

The COMEDY Is FINISHED

1

“Welcome to television, folks. If you’re very very good, we’ll renew ya for next week.”

Koo Davis is onstage, hand mike negligently held just below his round pink chin. He looks like that portrait of him done by Norman Rockwell over twenty years ago; everybody has that same warm pink latex face in Norman Rockwell portraits, but Koo Davis has it in real life. He’s the ultimate justification for the Norman Rockwell palette: “See? It is realistic!”

“This thing here,” Koo Davis is telling his studio audience, “is called a camera, and that thing there is called a cameraman. If he’s a union cameraman he’s called ‘sir’.”

The place is a television studio, with a wide shallow bleacher along one wall, on which sits a studio audience of two hundred fifty people. There isn’t any actual stage, simply the black-composition-floored work area, made into cubicles by muslin-walled sets, with three cameras in position: left, right, center. The center camera operates in a central break in the bleachers, so it isn’t in anybody’s view. The floor is here and there covered with neutral gray carpet, and everywhere strewn with cables, like strings of black and silver spaghetti. Three television sets hang from the ceiling, facing the audience; they are dark now, but during the taping they’ll show the progress to the audience as it’s being put together. Sitting on the rows of folding chairs on the bleachers are the first two hundred fifty people from the line that formed earlier this afternoon outside the studio. They all came in for free, and they’re looking forward to a good time.

“Now,” Koo tells them, “we’re gonna be together the next hour or so, while we put this show on tape, and if you’re a student of television and you wanna just sit there and watch the camera angles, that’s okay. And if you wanna laugh so hard you get a stitch in your side and fall down on the floor and roll around helpless with laughter, that’s okay, too. And we’ll be watching you all with monitors, and after the show we’ll tell you which of you can go home.”

Koo Davis does his own warm-ups. There are lesser comics who wait in their dressing rooms, talking with their agents and their accountants, while warm-up specialists (jolly-faced fiftyish failures with memorized repertoires) pep up the audience with semi-dirty jokes, get the audience already chuckling away, comfortable in its seats and ready to roar. But that isn’t Koo Davis’ style; his style is to find them where they are, grab them by the lapel, hit ’em with some yocks, hit ’em with some more yocks, and between times grin at ’em and walk around. He does confidence, that’s what Koo Davis does, because an audience digs confidence.

“We’re gonna have a couple special guests here on the show,” Koo Davis tells the people. “They’re actors, but you ought be nice to them anyway. I wanna tell ya, I’m always nice to actors. I learned my lesson. Last time I fired an actor, he got a job as Governor.” Little pause, grin at them while they laugh. “He wasn’t a very good actor, either.”

This is a new line of territory for Koo, a new kind of politics in the jokes, and he’s easing into it very cautiously, like into a tub of too-hot water. Behind the confident grin, the faintly swaggering walk, he’s watching how that Governor gag goes down, he’s waiting to see if they’ll accept it. That is, if they’ll accept it from Koo Davis. He’s got some fence-mending to do, and he’s not exactly sure how to go about it.

The trouble began with the goddamn Vietnam thing. That goddamn war cut the country in half, it put the white male middle class over on this side and every damn body else over on that side, and when it finally ended, for some damn reason Koo couldn’t let go. Others could, Duke Wayne and Shirley MacLaine right away kidding each other at the Academy Awards, but for Koo it was as though to admit the last step had been wrong meant admitting everything before it had also been wrong, and that he just couldn’t do.

The bitch of it is, Koo always stayed out of politics. He started on radio back in ’39, and it was the normal road then to follow the Will Rogers recipe; a couple jokes about Congress not doing anything, some jokes about Roosevelt’s alphabet soup, every comic in the business was doing it. But not Koo. He had an instinct, it said times change, it said people don’t really want to laugh at their leaders, it said leave the messages to Western Union. So Koo told jokes about the railroads, about the army, about automobiles and radio and California weather. And when World War Two came along he told jokes about nylons and chocolates and V-girls and let the other comics tell their jokes about the Nips. (Nobody told jokes about the Nazis; they weren’t funny enough.)

You always knew what year it was from Koo’s material, but never what the issues were. Housing shortage. Vets in college. Fins on cars. Men in space. Let Mort Sahl come onstage with a newspaper, Koo Davis walked on with a golf club. But then came the goddamn Vietnam thing, and the country was divided as it had never been before, and Koo just couldn’t help himself. Like everybody else, he had to come down on one side or the other:

“I didn’t know if it was a boy or a girl, and it turned out to be a sheepdog.”

“Of course, Canada’s a fine place for people with cold feet.”

Nobody needs a majority more than a comic. You’re standing there in front of all those faces and you say your line, and you don’t want six jerks in the corner with a tee-hee, you want every face split open. If you don’t have the instinct for the majority, you don’t make it as a comic. Koo went over to politics because the audience wanted it. Inside himself he had two conflicting instincts—give them what they want; stay out of politics—and he had to choose.

“Also with us tonight, a wonderful actress from Sweden, Birgit Söderman—that’s the way you pronounce it, folks. I said it wrong in a smorgasbord restaurant the other night and got pig’s knuckles. I used to make the same mistake with Juanita Izquerta, but then I got her knuckles.”

Poor reaction, drop-off in audience response. Koo walks around, grinning—“But I wanna tell you, I love working TV”—and in fifteen seconds he’s got them back, and he’s forgotten the dead spot. Most mistakes he remembers, but gags like the Juanita Izquerta he keeps in no matter how bad the response. The trouble is, not enough people remember the name. She was never a big star, Juanita, she made a dozen pictures in the early fifties and that was it. But Koo had her along on some of his USO tours—the boys in Korea, that decade—and his female co-stars, the starlets and has-beens and almost-wases he trouped and shtupped on those tours, are always fresh in his mind, as though they’re still this minute young hard-breasted terrific chicks knocking them dead tonight in Vegas or Miami Beach just as Koo himself is knocking them dead here at this taping of The Koo Davis Special in beautiful downtown Burbank, California. It’s as though there’s a loyalty he owes those girls, to pretend they’re still hot stuff, still hot, that it could still be any one of them appearing on this show with him instead of the latest blonde, Jill Johnson, a laid-back girl comic of the new school, 26 and a sexual bearcat, with whom he would be cheerfully expending his post-tape hard-on. (Performing has always been good for his sex life.)

Even the first of the blondes, Honeydew Leontine, on his premier tour—Hawaii, Australia, a few shitty islands, a couple aircraft carrier flight decks—even Honeydew, a girl whose movie career never got higher than stooge for the Ritz Brothers and was over even before the end of World War Two, even Honeydew still shows up from time to time in his monologues, and the last time he’d trouped and shtupped with Honeydew was—Christ on a crutch, it was over thirty years ago! The first time, in Hawaii, was thirty-six years ago! Jesus! Honeydew and her big tits and her collection of stones—stones from every goddamn beach she’d ever walked on, she carried them around in burlap bags, everywhere she went—Honeydew must be almost sixty fucking years old by now. And Koo himself, if he stops to think about it, which he never does, is sixty-three.

“Of course, television is different from the movies. When I started in pictures—I won’t say how long ago that was, but I taught William S. Hart how to ride—and in the old days you’d shoot the same scene over and over until the director was satisfied. It got to be a habit to repeat things until you got them right. It got to be a habit to repeat things until you got them right. It got to be a habit to repeat things until you got them right. It got to be a—”

Which is about par for that gag; the laugh starts at the beginning of the first repeat, a trickle that dwindles off, picks up again at the beginning of the second repeat, lulls, then picks itself up again before the finish of the second repeat (the audience anticipating the third), so Koo is pushing the third repeat into a growing laugh. Then he can stop and do his own laugh, and grin, and shake his head, and walk around, selecting the next gag while the audience works on the last one.

It was the USO taught Koo how to be a comedian. He’d done vaudeville, he’d done radio, he was already what was then called a “headliner,” but it was the USO tours that taught him how to live with an audience, how to make it want to like him, how to make it feel afterward that he didn’t just make them laugh, he made them happy. In those early days he was just another radio comic, and the point of the touring shows was to give the troops a safe acceptable look at American tits and asses, so what he had to do when he stepped out on that temporary stage was give the GIs a reason to be happy to see him. Give them topical jokes (“Actually, I’m just here to buy cigarettes.”), give them local jokes (“General Floyd sent me a message not to fraternize with the natives. At least that’s what the mama-san told me, when she hung up the phone.”), then bring out Honeydew or Juanita or Laura or Linda or Karen or Lauren or Dolly or Fanny, run a couple dumb-blonde routines, leave the chick out there to sing a song, come back with the local commander (they were all hams at heart, every last one of them), do a little uplift, cut it with some mild sex gags, send the General or Admiral or Colonel or Commander off with Juanita or Linda or Lauren or Dolly, give their exit an innuendo the troops could enjoy, and by then they were his, because he was their link to special status. They were dogfaces, retreads, grunts, and he was hanging around with Generals and blonde chicks, but he was one of them. He could come on like the rawest of raw recruits (“Colonel O’Malley’s being terrific to us all. He’s gonna watch Honeydew for me while I go up all by myself to the rest camp at Bloody Nose Ridge.” Or Pork Chop Hill, or St. Lo, or wherever the most dangerous spot in the neighborhood might be.), and he could come on like the cool wiseguy the troops all wished they were, and they learned to love him for it, and he learned to love them for loving him.

He got a lot of good press for the USO work, and in truth he deserved it. He made no money out of it, not directly, beyond the expenses of the troupe. He’d started the tours in the first place because he was medically 4-F in 1940 (bad ear and bad stomach and bad knee), and he felt guilty about it, and this was something he could do to make up for not being “in it.” (He wound up “in it,” in fact, more than most guys in uniform, being under fire or otherwise in danger countless times while riding in jeeps or trucks or planes or helicopters or transport ships or—once, on Okinawa, when three kamikazes came plunging through the ack-ack—in a rickshaw. “We have some wild drivers in California,” he told the troops that afternoon, “but those three that came through this morning were ridiculous.”)

And when the goddamn Vietnam thing came along, how was he supposed to know it was different? Why wasn’t it the Pacific Theater all over again, Korea all over again? It hadn’t been wrong to cheer our side ever before, and these were the same kids, weren’t they? Fighting the same slant-eyed son of a bitch gooks, weren’t they? So what the hell was the difference?

Permissiveness, it seemed like. A lot of fat, soft college kids hanging around on their campuses, young snotnoses, didn’t know their ass from their elbow. You looked at the real kids marching along in the same uniforms as before, you knew you had to make a choice, and Jesus the choice seemed easy. It should have been Stage Door Canteen all over again, it should have been, but it wasn’t.

Koo did the USO tours the same as ever, but when he was in the States the great National Debate was creeping into his comedy, and for the first time in his career he was coming out on stage and getting booed. Half the under-twenty-fives out there in America thought he was some sort of goddamn baby raper or something. He just couldn’t figure it out, and it made him mad, and the jokes got more and more political, and everything was just simply out of control.

He still doesn’t know why the goddamn Vietnam thing was different, but fairly early on he understood it was different. Maybe the slant-eyed gooks were the same (he wasn’t even sure about that anymore), and maybe the American uniforms were the same, but the kids inside that olive drab were something else. They laughed at the space-shot jokes and the bureaucracy jokes and the sex jokes (“I was supposed to do a nude centerfold for Cosmopolitan but it didn’t work out. They said all the interesting parts were behind the staple.”), but there were tried-and-true lines they didn’t laugh at. “The General’s being terrific to us all. He’s gonna watch Dolly for me while I go up all by myself to the rest camp at Khe Sanh.” They gave him a polite chuckle. They didn’t want to embarrass him, the sons of bitches, and they were polite to him!

You’re polite to a comedian, you’re killing him.

Then, when Vietnam ended, you couldn’t throw an asparagus spear without hitting six hypocrites. But not Koo; he wasn’t sure why he even had these convictions, but he’d stick by them. The career was thinning out, TV sponsors weren’t picking up their options, it was getting tougher to find writers whose material Koo could even understand, and he began to think long thoughts about retirement. He remained steadfast through the Nixon resignation and the Ford pardon, he even stuck when nobody invited him on that goddamn aircraft carrier in New York on Bicentennial Day; July 4, 1976, the Tall Ships, and Koo watched it on television. He’d offered to work for the Ford campaign, and they’d gently let him down, and it wasn’t till later he figured it out; Koo Davis had become a reminder of too much bad history. Koo Davis!

But what did it for him at last was the investigations into the CIA, where it was made public that for several years in the sixties they’d had a phone tap and a mail check on him! On Koo! And when the asshole involved was asked by the Senate Committee why Koo Davis, the answer was that Koo had a lot of liberal friends. Did have.

Right after that came the revelations about the CIA experiments on human beings in hospitals, and that just put the icing on the cake. Maybe nobody else remembered what the Second World War had been all about, but Koo did, and he got mad: “The purpose of the experiments was to see if a human being could live without a brain. It turns out he can, if he’s in the CIA.” And when it occurred to him he was now telling anti-government jokes, he realized the time had come to end his own long war. Back to civilian life, back to the home front, back to the world he’d left behind.

“And if you don’t like the show, folks, you’ll get a full refund at the door. But I know you’re gonna love it, and now I gotta go get ready, we’re in kind of a hurry today, the manufacturer is recalling my pacemaker.”

With a grin, with a wave, Koo tosses the mike to a waiting stage-hand and trots off. “It’s a good audience,” he tells somebody on the way by, but that’s just words, he doesn’t even know who he’s talking to. They’re all good audiences for Koo Davis, they’ve been good audiences again for a year now. The split is over, the trouble’s over, everybody’s a good guy after all, and Koo is happy to relax once more into who he really is; a funny man, a funnyman, a good comic, an honest uncomplicated human being, living like every comic in the eternal Now, the Present, the Hereheisfolks, the Nowappearing. It’s a good life, safe at last, and it’s always happening right Now.

Koo has three minutes to drink a little ice water, get the makeup adjusted, have a quick last look at the script, play a little grabass with Jill, and then come out stage center into a group of eight tall lean dancing girls and his opening line of the show: “I can remember when legs like that were illegal.” Now, he moves briskly along a cable-strewn alley created by the false walls of stacked sets, toward the door to a corridor leading to his dressing room, and as he reaches that first door somebody on his left says, “Mr. Davis?”

Koo turns his head. It’s one of the scruffy bearded young crew members; these hairy sloppy styles never will look to Koo like anything but shit. Behind the kid is a side exit from the studio, the red Taping light agleam above it. Koo is in a hurry, and he wants no problems. “What’s up?”

“Look at this, Mr. Davis,” the kid says, and brings his hand up from his side, and when Koo looks down he is absolutely incredibly dumbfounded to see the kid is holding a pistol, a little black stubby-nosed revolver, and it’s pointed right at Koo’s head. Assassination! he thinks, though why anyone would want to assassinate him he has no idea, but on the other hand he has in his time played golf with one or two politicians who were later assassinated, and in his astonishment he opens his mouth to holler, and the kid uses his free hand to slap Koo very hard across the face.

And now a bag gets pulled down over his head from behind, a burlap bag smelling of moist earth and potatoes, and cable-like arms are grabbing him hard around the upper arms and chest, imprisoning him, lifting him, lifting his feet off the floor. He’s being carried, there’s a sudden rush of cooler air on the backs of his hands, they’re taking him outside. “Hey!” he yells, and somebody punches him very very hard on the nose. Jesus Christ, he thinks, not hollering anymore. Now they’re punching me on the nose.

2

Peter Dinely watched the blue van with Joyce at the wheel jounce slowly over the speed bumps at the studio exit and turn right toward Barham Boulevard. Were Mark and Larry in the back, out of sight? Did they have Koo Davis back there? Peter gnawed the insides of his cheeks, willing Joyce to look this way, give him some sort of sign, but the van turned and drove unsteadily away, an enigmatic blue box on small wheels, its rear windows dark and dusty. Peter followed, in the green rented Impala, the ache in his cheeks a kind of distraction from uncertainty.

The habit of gnawing his cheeks was an acquired one, chosen deliberately a long long time ago and now so ingrained he could no longer stop it, though the inside of his mouth was ragged and even occasionally bleeding. If he ever could stop chewing on himself he’d be glad of it; but then would the blinking come back?

Peter was thirty-four. To break an early habit of blinking when under pressure, he’d been chewing his cheeks in moments of tension for fifteen years. Eleven years ago a dentist had reacted with horror, telling him the interior of his mouth was one great raw wound, since when he had stopped going to dentists.

Now, Peter followed the blue van west on Barham Boulevard, and it wasn’t until the turn onto Hollywood Freeway northbound that he could angle into the middle lane, run up next to the van, look over at Joyce’s tense profile, and tap the horn. She looked at him almost with terror, not seeming to understand what he wanted—or possibly even who he was—until he gave her an angry questioning glare while pointing with jabbing fingers at the back part of the van. Then she gave a sudden jerk of understanding, and an exaggerated nod. Yes? he asked, demanding with head and face and arm, and she nodded again, with a small tense smile and a quick jerky wave of the hand.

All right. All right. Peter became calm, his shoulders sagging, his jaw muscles relaxing, the blood oozing into his mouth, his foot easing on the accelerator. The Impala dropped back and tucked in once more behind the blue van. Everything was going to be all right.

The house was in Tarzana, up in the hills south of the Ventura Freeway. Peter waited behind the van as Joyce stopped at the gate and her hand reached out to ring the bell in the metal pole beside the driveway. There was a pause—up above, Liz must walk to the kitchen, ask for identification through the speaker, receive reassurance from Joyce, then press the button—and then the wide chain-link gate slowly opened and the van jolted up the hill. Peter followed, seeing in the rearview mirror the gate automatically swing shut.

At the top, the blacktop driveway leveled off into a flat area in front of the wide garage. Next to it, the house was a broad ranch-style in brick and wood; as the two vehicles came to a stop, Liz came out its front door. She was naked, her long lean body hard-looking, her eyes hidden behind large dark sunglasses. It was Liz’ style to be aggressive and challenging; neither Peter nor any of the others would remark upon her nakedness.

Getting out of the Impala, Peter opened the rear doors of the van and there they were. Koo Davis, head still enclosed in the burlap sack, lay face down on an old double-bed mattress. Mark, bearded and stolid, sat at this end of the van, his feet stretched out over Davis’ legs, while worried-looking Larry perched uncomfortably up front by Davis’ head. “Very good,” Peter said. “Get him out of there.”

Davis didn’t speak as they helped him out to the blacktop; Peter, taking his arm to assist, felt the man trembling. “Just walk,” he said.

Liz led the way into the house. When she turned her back the scars were visible; twisted rough-grained white lines that would never take a tan, criss-crossing down the middle of her back.

The interior of the house was cool with central air-conditioning. Pale green carpet on all the floors muffled sound. While Joyce and Mark stayed behind, Peter and Larry guided Davis through the house, following Liz. In the kitchen, she opened a narrow door and they went down a narrow staircase to the left. Here, beneath the house, were the utilities, in a small square concrete block room without frills. Cardboard wine cartons were messily piled in one corner, behind the pool heater. On a side where it wouldn’t be expected was a door, which Liz opened, revealing a fairly long narrow room which extended out from the house underneath the sun deck as far as the swimming pool. At the far end of the room was a thick glass picture window, with the green-blue water at the deep end of the pool restlessly moving against its other side. Daylight filtering through that water made a cool gray dimness in here, until Liz touched a switch beside the door which brought up warm amber indirect lighting.

The first owner of this house had been a movie director, who had added several ideas of his own to the architects’ plans, including this room, in which it was possible to sit and have a drink and get a fish-eye view of one’s guests swimming in the pool. The director had enjoyed this idea so much he’d had the setting written into one of his movies, and shot the scene in this room.

The room was plain but comfortable, with maroon cloth on the walls, low overstuffed swivel chairs, dark carpeting, soundproofed ceiling, built-in bar sink and refrigerator, several small low tables, and in one corner a door leading to a small lavatory, with shower, sink and toilet. In readiness for Koo Davis, the refrigerator had been stocked with simple foods, more ready-to-eat food was stacked on the shelf above it, some plastic plates and cups and spoons had been placed on a table, and even a plastic decanter filled with inexpensive Scotch had been provided.

Once they were all in the room, Larry pulled off the burlap bag, and Peter looked at the familiar face of Koo Davis. His sense of accomplishment was so strong that this time he had to bite his cheeks not to ease tension but to keep himself from smiling.

Davis had had a nosebleed, which had stopped, leaving smudges of brown under his nose and along his left cheek. He looked frightened but cocky, as though he’d decided his game plan was to tough it out.

Larry, of course, reacted big to the nosebleed, saying, “Oh, we’re sorry about that! Your nose!”

Davis looked at him in mock astonishment. “You’re sorry about my nose? If you’ll notice, you took the whole body.”

Peter said, “If you’ll notice, you’re in a room with one door, which we’ll keep locked. You have food there, drink there, and a toilet over there.”

Glancing around, Davis said, “Okay if I open the window?”

“This isn’t a joke,” Liz told him. She had removed her sunglasses, and her eyes and voice were as hard as her nude body.

Davis grinned at her. “I’ll be able to identify you later on,” he said. “Anyway, I’m looking forward to the lineup.”

“That fine, Koo,” Peter said, permitting himself a small grin. “You keep your spirits up.” To Liz and Larry he said, “Come on.”

Davis, suddenly less jocular, said, “Do I get a question?”

Amused, Peter said, “Which question? Why? Who? What?”

“I thought kidnappers didn’t want to be recognized. Unless they figured to kill the customer.”

Jumping in, looking very intense, Larry said, “We’re not going to kill you, Mr. Davis.”

“Assuming things go well,” Peter said. “Assuming everybody is sensible, Koo, including you.”

“That’s a big relief,” Davis said. Terror was pulsing just beneath his cocky surface, like a kitten under a blanket. “As long as I go on being sensible, I’m okay, right? I mean, sensible like you people.”

“That’s right,” Peter said.

3

“So here I am on the bricks,” Mike Wiskiel said. He felt goddamn sorry for himself. “Lemme tell ya, Jerry, the worst word in the English language is the word ‘retroactive.’ You can forget all about ‘it might have been’ and ‘nevermore’ and all that crap, the word is ‘retroactive.’ It’ll fuck ya every time.” And he swallowed another mouthful of vodka and tonic, while Jerry chuckled his friendly, agreeable, meaningless realtor’s chuckle.

Mike Wiskiel was a little drunk, at four in the afternoon; not for the first time. He’d spent the morning talking to women who’d sent in eleven bucks for a scalp-invigorator that when they’d tried it made their hair fall out, and by lunchtime he’d seen enough bald women to last him the rest of his life. So he’d come here to the club for a quick game of tennis and the Daily Special lunch—today it was avocado followed by abalone, washed down with a Napa Riesling—and then he’d run into Jerry Lawson in the bar and here he still was, sitting at a table by the tinted-glass windows, having another little drink, at four on the clock in the pee em. And at this moment he and Jerry were the only members present in the bar.

Jerry Lawson was a real estate agent, and probably Mike’s closest friend out here, apart from the people at the Bureau. Mike had met him—Jesus, almost a year ago—when he’d been transferred to the L.A. office and had made the exploratory trip to find a new house for Jan and the kids. He’d walked into the real estate office on Ventura Boulevard, and the first thing he’d ever said to Jerry was, “I know you from someplace,” and he remembered thinking, Jesus, maybe this guy is on the hot list. But Jerry had gripped and said, “I’m the guy shot June Havoc in The Sound of Distant Drums,” and wasn’t that L.A. for you? Your real estate man turns out to be a one-time actor.

And a good friend. Jerry had found them a perfect house, up in the hills in Sherman Oaks, and had even put up Mike’s name for his country club, El Sueno de Suerte, here in Encino. Of course, it’s true that in Los Angeles realtors keep in closer touch with their former clients than elsewhere, since the average turnover of a middle-level-and-up house in that city is two and a half years, but Mike was convinced in this case it was more than the usual business friendship. He and Jerry enjoyed tennis together, drinks together, poker and barbecue and a good laugh together, and the wives got along, and even the kids from both families didn’t seem to hate each other one hundred percent of the time. Jerry’s friendship had helped a lot to soften the blow of having been transferred out here through no fault of his own. After all those years, back on the bricks.

He repeated it aloud. “Back on the bricks. I tell ya, Jerry, I had it made at the Head Office, it didn’t matter who the Director was. They knew I was a reliable man, they knew I was loyal, they knew I delivered. ‘I don’t want excuses, I want results,’ that’s what the Director used to say, and nobody ever heard an excuse from me.”

“I know,” Jerry said sympathetically, though he could only know what Mike told him. “You got your nuts in the wringer, that’s all. That’s all that happened.”

“Retroactive,” Mike said, dealing with the word as though it were a pebble he was moving around in his mouth. “ ‘Do this,’ they said, ‘it’s your patriotic duty.’ ‘Oh, yessir,’ I said, and salute the son of a bitch, and I go do it, and when I come back there’s some other son of a bitch in there and he says, ‘Oh, no, that wasn’t patriotic, it was illegal and you shouldn’t of done it.’ And I say, ‘Why I got my orders right here, I’m covered, I got everything in black and white, this is the guy told me what to do,’ and they say, ‘Oh, yeah, we know about him, he’s out on his ear, he’s in worse trouble than you are.’ So that guy’s ass is in a sling and my nuts are in a wringer and Al Capone is up there at San Clemente in a golf cart. And who’s loyal now, huh? Who do you trust now, the shitter or the shit-upon?”

“It’s a tough racket,” Jerry said. He was a terrific sounding board, he never confused the conversation with a lot of dumb suggestions.

“You’re fuckin A,” Mike told him, and turned to point at Rodney the barman. “Twice again,” he called, and the beeper in his jacket pocket went EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE. “Shit,” Mike said, under the noise of the machine, and reached to shut it off.

Jerry looked interested. “The office?”

“More fuckin bald women,” Mike said, and twisted around the other way to holler over at Ricci the waiter, “Bring me a phone, will ya, Rick?”

The phone came first. Ricci plugged it into the jack under the window, then went off to get the drinks while Mike phoned the office.

“Federal Bureau of Investigation.”

“Extension twelve.”

A few burrs, and then: “Agent Dodd.”

“Mike Wiskiel here. I was just buzzed.”

“Hold on, Redburn wants you.”

The drinks arrived while Mike was holding on, and he signed for them with the receiver tucked in against his shoulder. Jerry said, “What’s up?”

“Dunno yet.”

Ricci took the tab away, Mike slugged down about a third of the new drink, and the voice of Chief of Station Webster Redburn came on the line: “Mike? Where are you?”

“At the club, Wes. I spent all day on that mail fraud case, I just came in for a little late lunch.”

“Forget the mail fraud and lunch,” Redburn said, and went on to tell him what had happened. Mike’s eyes widened as he listened, and he knew there’d be no more paperwork, no more routine slog, no more bald women and low-IQ bank robbers and stolen cars, no more day-by-day boring bullshit, not for hours, not for days, maybe even not for weeks. “So get there fast,” Redburn finished.

“I just left,” Mike told him, and cradled the phone.

Jerry looked as inquisitive as a cat who’s just heard a noise under the refrigerator. “What’s up?”

“A james dandy,” Mike told him. “Somebody put the snatch on Koo Davis! Would you believe it?” And, getting to his feet, he downed the rest of his drink and trotted from the room.

I need this, Mike told himself. I gotta do good on this one. Fuzzy from that last vodka, he sped east on the Ventura Freeway while a golden future opened up before his bleary eyes; if he did good on this Koo Davis thing. Yes, sir. They’d have to transfer him back to Washington then, they’d have no choice. Back where he belonged.

Yes, sir. Old Mike Wiskiel, fucked over because of Watergate, kicked out of D.C., rescues Koo Davis from the kidnappers! Talk about your media blitz! Mike could see his own fucking face on the fucking cover of Time magazine. “Tough but tender, FBI man Mike Wiskiel counts persistence among his primary virtues.” Writing the Time article in his head, pushing the speed limit, not quite grazing the cars to left and right, Mike Wiskiel raced to the rescue.

The gate guard at Screen Service Studios gave Mike’s ID a very careful belligerent screening. Mike didn’t need this shit; he was more sober now, but the buzz of vodka was steadily souring toward a headache. He said, “Locking the door now the horse is gone, huh?”

The guard glared but made no remark, simply handing back the ID and saying, “Soundstage Four. Past the pile of lumber up there and around to your left.”

Mike grunted, and drove cautiously forward. The speed bumps weren’t that good for his head.

Following the guard’s directions, Mike soon saw a large black number 4 painted on an otherwise featureless gray wall, above a gray metal door. Several cars, most of them official-looking, were parked in a cluster along the wall, and two Burbank cops were standing together outside the door, chatting in a bored way and looking around for stars.

There weren’t any stars, not right now. Except for the two Burbank cops there was nobody in sight. Mike didn’t know those two—his acquaintanceship among the bewildering multiplicity of police forces in the Greater Los Angeles area was very low—but he waved to them anyway as he drove by, looking for a place to park. They responded with flat looks, and when he left the car and walked back these Burbank cops also gave his ID a tight aggressive inspection. Mike said, “I understand the snatch took place about three-thirty, am I right?”

“That’s right.”

“Then that was the time to check ID. One thing you’re not gonna get right now is the kidnappers sneaking back in here disguised as FBI men.”

They both looked sullen. One of them said, “You could be a reporter.”

“Flashing Federal ID? I’m some fucking stupid reporter.” And he went inside.

Almost any of the other agents in the Los Angeles office, with their local police contacts, would have been better qualified than Mike to be liaison on this case, except that the victim was Koo Davis; a famous name, a celebrity, and a man with lots of official friends back in D.C. No one lower-ranking than Assistant to the Chief of Station could possibly be sent to cover the first day, when legally the FBI’s connection with kidnapping—a state, not federal, crime—was advisory only; which was why it was Mike’s baby. And his big chance.

He had no idea, on walking into Soundstage Four, whether the local law would welcome him with open arms or closed faces, but it turned out he was in luck. The local man in charge, a tall leathery old duff called Chief Inspector Jock Cayzer, seemed both friendly and competent, and started right off by saying, “FBI, huh? Good to have you aboard.”

Cayzer had a hard strong handshake. He wore a brown suit and a string tie and a Stetson, and he talked with the gruff slow twang of Texas or Oklahoma, but the deep creases in his face and the knobby knuckles of his blunt-fingered hands said plainer than words that he was the real thing and not one of the million imitations spawned in the Los Angeles area. Despite the strong handshake, and the keen look in his silver-flecked blue eyes, and his strong deep voice, he was surely older than the mandatory retirement age, so his still being here, actively in charge, meant he either knew his business or knew the right people. Probably both. So Mike had better be careful with him.

He knew his business, that much was sure. He took Mike around the building, explaining the situation, and Mike could only agree with everything Cayzer had so far chosen to do. What had happened, Koo Davis had been on stage talking with the studio audience before taping his program, and on his way back to the dressing room—down this corridor, through this door, along that hall—he’d disappeared; probably out this door, leading to this alley. Presumably he’d been snatched, though so far there’d been no word from the kidnappers. On the other hand, the kidnapping (if that’s what it was) had taken place barely half an hour ago: “They might not even be gone to ground yet,” Cayzer said.

As to who they were, and how they might have done it, there were some clues, beginning with that studio audience. In normal movie studio fashion, Triple S was under controlled access, with high walls or fences all around the property and only two usable gates, both manned by private guards. The minute the alarm had reached Cayzer’s office, he had ordered the lot sealed; no one off, no matter who they were or what their reason, and only police and other authorized officials on. The result was, the studio audience that had come to see Koo Davis was still here, undergoing a kind of thrilled boredom. They’d been told what had happened and that they wouldn’t be permitted to leave just yet, so they knew they were involved in a very dramatic moment, but on the other hand they were just sitting there on those bleachers, with nothing to do and nothing to see.

And they were two short. “They keep a headcount,” Cayzer explained. “They get a mob comes to these things, but they only let in the first two hundred and fifty, that’s final, no more and no less. I’ve had three of these studio fellas swear to me up and down and sideways there was exactly two hundred fifty people let in today, and we done our own headcount, and now there’s two hundred forty-eight.”

“So that’s how they got in,” Mike agreed. “The next question is, how’d they get out?”

“I do believe we got a hint on that,” Cayzer said. “Two of my men talked to the fellas on the main gate, asking who come in and out during the ten minutes between Davis disappearing and us closing the place down, and we got one good-looking prospect. A Ford Econoline van, belongs to one of the girls works in the studio offices. The fella on the gate remembered it because she only brings it in on Fridays and she usually leaves later in the day. Girl’s name is Janet Grey, she’s been working here less than two months, she didn’t ask her boss’ permission before she took off early.”

“Sounds good,” Mike said. “You got an address?”

“Down in West L.A. County boys looking into it now.”

“She won’t be there,” Mike said.

Cayzer grinned, making another thousand creases in his face. His eyes were meant for seeing across open miles, they seemed too powerful for small rooms, small concerns. “I’ll be surprised, there’s even such an address,” he said.

Mike said, “What about the family?”

“Well, that’s sort of a problem,” Cayzer said. “Seems Davis’s separated from his wife, she’s out in Palm Beach, Florida. Then he’s got two sons, both grown up, one of them in the television business in New York, the other one lives in London. Your boss said—”

“Webster Redburn.”

“That’s him; Chief of Station. He said his people would see about notification of the family. We got no relatives around this part of the world at all. The closest we can come is Davis’ agent, a woman called Lynsey Rayne. She’s waiting in my office right now for news.”

“We could all use some news,” Mike said. “What’s your next move?”

“I have men searching this whole lot,” Cayzer said. “Indoors and out. Don’t expect they’ll come up with anything.”

“Probably not. These people hit and run.”

“That’s right. Then there’s that audience. I think I might’s well let them go, unless you want them.”

“This is your show,” Mike said. “I’m just an observer.”

“Oh, I think we could work together right from now,” Cayzer said. His grin, it seemed, could develop a sly twist at the left corner. “Less you’d rather wait till tomorrow.”

“Anything I can do to help,” Mike promised, “just let me know.”

“Fine. Think I oughta let that audience go home?”

“Did you talk to them about pictures?”

Cayzer looked blank. “Pictures?”

“Snapshots.”

“Well, god damn it,” Cayzer said. “Sometimes I don’t know if I was stupid all my life or if I’m just getting stupid with old age. Come on along, you can ask them yourself.”

Mike followed Cayzer to a large soundstage full of sets and cameras, with an audience-full line of bleachers along one side. A technician gave him a hand mike, and he stepped out into the floodlights, where forty minutes ago Koo Davis had been making people laugh. Now his absence was making the same people wide-eyed with anticipation, and Mike was strongly aware of all those eyes glittering at him out of the semi-dark. He was also strongly aware of the floodlights; they were making his headache worse. His eyes felt as though the pressure behind them would make them pop out onto the floor; and good riddance.

With the bleachers so broad and shallow, the audience was much closer to the stage than in a normal theater, and Mike immediately had the sense that these people were still an audience, still spectators rather than participants. They were waiting for him to amuse them, thrill them, capture their interest.

He did the latter merely by introducing himself: “Ladies and gentleman, my name is Michael Wiskiel. I’m an agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, here to assist Chief Inspector Cayzer in his inquiry.” His inquiry; the social niceties are important everywhere. “Now, I imagine some of you nice people are tourists in this area, and all of you have your own lives you want to get on with, so we’ll try not to hold you up very much longer. I suppose some of you brought cameras along today, I wonder if any of you have Polaroids. Anybody?”

A scattering of hands was raised; Mike counted six.

“Fine. So any pictures you folks took today, you’ve already got them in your pocket or purse, all developed and ready to be looked at. I wonder, did any of you people happen to take any pictures while you were out on line, before you got in here, and would those pictures show anybody else in the line?”

A stir in the audience, as two hundred forty-two people turned in their seats to watch six people self-consciously leaf through little clusters of photographs. Four of them eventually turned out to have pictures of the sort Mike had in mind, and ushers brought these photographs to the stage.

Seven snaps. Mike looked at the first, and saw four more-or-less distinguishable people behind the smiling squinting foreground lady who was the obvious subject of the photograph. He called out, “Could we have some light on the audience?” and immediately a bank of overhead spots came up, lighting the audience as though it had become the stage.

“Let’s see now,” Mike said. “Here’s a young man in a pale blue sweater, black hair, wearing sunglasses. Anybody?”

The young man was found, and when he stood and put on his sunglasses Mike matched him to the photograph. Also the lady wearing the white scarf and green polka dots. And also the elderly couple in matching white turtleneck shirts.

And so on through the seven Polaroids. Every identifiable face was still among the two hundred forty-eight. Either the two kidnappers had been very careful or very lucky.

“Well, it was worth a try,” Mike told the audience, when the pictures had been returned to their owners. “So now let me ask about other cameras, where you’ve still got the film inside. Anybody?”

More: thirty-five hands went up. Mike arranged with Cayzer to have police officers collect the film rolls, identifying the owner of each, and promising that the pictures would be developed, all developed prints and negatives would be returned to their owners, and reimbursement would be made for unused parts of rolls.

“Now, one last thing,” Mike said, when the film had been collected. “We’ll want group pictures of you all. If you were wearing something outside on line that you’re not wearing now, like sunglasses or a hat, please wear it in the picture.” There’s something about standing on stage with a hand mike that compulsively brings out the ham in everybody; Mike couldn’t resist adding, “And if you’re here with somebody you shouldn’t be, don’t worry, we won’t say a word to your wife.” The answering chuckle, from two hundred forty-eight throats, delighted him.

While Cayzer’s men took the pictures, section by section, and copied down the names and addresses of everybody present, with their location in each photograph, Mike and Cayzer had a talk behind the set, Cayzer saying, “My people finished their search of the lot. Nothing, nobody, no report.”

“What we expected.”

“That’s right. You want to talk to Janet Grey’s co-workers?”

In a cracking, terrible falsetto, Mike said, “Oh, I just can’t believe Janet would be involved in anything like this. She was always such a quiet girl, she just kept to herself all the time, a very good worker, never made any trouble or called attention to herself in any way.”

Grinning, nodding, Cayzer said, “You just saved yourself an hour and a half. So what do you want to do next?”

“Hear from the kidnappers,” Mike said.

4

Koo Davis is in trouble, and he knows it, but he doesn’t know why. And he doesn’t know who, or how, or even where. Where the hell is this place? An underground room with a bar and a john and a cunt-level view of a swimming pool; the naked girl with the scars on her back spent half an hour paddling around in the water out there, after Koo was locked in. She swam and dove, the whole time pretending there wasn’t any window or anybody watching, and all in all Koo was very happy when she finally got her ass out of the pool and left him in peace. She has a fantastic body when you can’t see the scars, but she doesn’t turn him on. Just the opposite: having that cold bitch flaunt herself like that shows just how little he matters to these people. They kidnapped him, they probably figure to sell him back for a nice profit, but other than as merchandise they couldn’t care shit about him, and that makes Koo very nervous.

Why me? he asks himself, over and over, but he never comes up with an answer. Because he has a few bucks? But Jesus, a lot of people have a few bucks. Do they think he’s a millionaire or something? If they ask for too much money, and if they don’t believe the answer they get, what will they do?

Koo doesn’t like to think about that. Every time his thoughts bring him this far, he quickly switches to another of his questions; like, for instance, Where am I? Still somewhere in the Greater Los Angeles area, that’s for sure. He estimates he was no more than half an hour in that truck or whatever it was. From the turns, this way and that, when they took him away from Triple S, he’s come to the conclusion they drove first on the Hollywood Freeway and then either the Ventura Freeway west or the Pasadena Freeway east; probably Ventura, out across the Valley. Then at the very end they did some climbing, with a particularly steep part after one fairly long stop. So he’s most likely on an estate somewhere in the Hollywood Hills, on the north slope, overlooking the Valley. And not some cheapjack place either, not with this room next to the pool. Somebody spent money on this layout.

Why do they want to keep him from identifying this place, yet they don’t care if he sees their faces? And why the fuck would rich people play kidnapper? These clowns operate like they’re at home here, they’re not worried about the owners coming back and interrupting the operation, so they must—

Unless they killed the owners.

Time to switch to another question. Like: Who exactly do they deal with, these kidnappers, who do they put the arm on? The network? Chairman Williams and the vice-presidents, that crowd of Easter Island statues? You can’t get blood from stone faces; if Koo knew his businessmen—and he did—Williams wouldn’t pay more than three bucks to get his sister back from Charles Manson.

But who else was there? Lily? “Hello, we got your husband Koo here, you remember him. He’s for sale.” How much would Lily pay for a living Koo Davis?

Koo is something of a showbiz oddity, a man who’s been married to the same woman for forty-one years; but that isn’t quite the record it sounds. As he once explained to an interviewer (in an answer cut from the published interview at Koo’s insistence), “You want my formula for a happy marriage? Marry only once, leave town, and never go back.”

Which is almost the truth. When twenty-two-year-old Koo married seventeen-year-old Lily Palk, back there in nineteen thirty-six, how could he know he was going to be bigtime any minute? Naturally he had his dreams, every kid has dreams, but there was no reason to believe his dreams were any less bullshit than anybody else’s.

If an insecure punk kid marries a practical girl, and if three years later the punk is a radio star in New York while the practical girl is a housewife and mother in Syosset, Long Island, the prognosis for the marriage is unlikely to be good: “I won’t be home tonight, honey, I’m staying here in town.” As he commented one time to a gagwriter pal named Mel Wolfe, “I got to put that on a record. Then somebody in the office can call the frau and play it at her. ‘Hi, honey, I won’t be home tonight, I’m staying in town.’ Then a little pause and I say, ‘Well, I wouldn’t if I didn’t have to. Everything okay there?’ Then another little pause and I say, ‘That’s fine.’ One more pause and I say, ‘You, too. Have a good night, honey.’ And meantime I’m in Sardi’s.”

“Hey, listen,” Mel Wolfe said. “I got a terrific—Feed it to me. Do the record.”

“Yeah?” Grinning in anticipation, Koo said, “Hi, honey, I won’t be home tonight, I’m staying in town.”

In a shrill angry falsetto, Mel Wolfe replied, “I went to the doctor today, you bastard, and you