Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: The Carrion City

- Sprache: Englisch

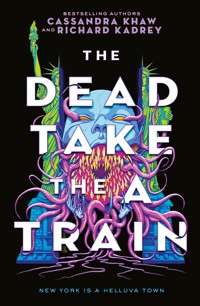

A gritty, explosive and bloody cosmic horror, Buffy meets American Psycho, about a roguish magical fixer, who is the only thing stopping the finance industry from summoning the eldritch beings they worship and serve. Julie Crews is a coked-up, burnt-out thirty-something who packs a lot of magic into her small body. She's trying to establish herself as a major Psychic Operative in the NYC magic scene, and she'll work the most gruesome gigs to claw her way to the top. Desperate to break the dead-end grind, Julie summons a guardian angel for a quick career boost. But when her power grab accidentally releases an elder god hellbent on the annihilation of our galaxy, the body count rises rapidly. The Dead Take the A Train is a high-octane cocktail of Khaw's cosmic horror and Kadrey's gritty fantasy—shaken, not stirred.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 596

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Also Available From Titan Books

Also by Cassandra Khaw and available from Titan Books

Nothing But Blackened Teeth

The Salt Grows Heavy

Also by Richard Kadrey and available from Titan Books

The Pale House Devil

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Dead Take the A Train

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781803368009

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803368016

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd 144

Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: October 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Zoe Khaw Joo Ee and Richard Kadrey 2023.

Zoe Khaw Joo Ee and Richard Kadrey assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To David Southwell, the Lord Mayor of Hookland

ONE

There were few things in life Julie Crews enjoyed more than bachelorette parties. They were, by design, one of those rare events where women weren’t just permitted but encouraged to throw off their inhibitions. No matter the amount of booze or the quantity of strippers, the drugs or the homoerotic shenanigans, the shrieking, the woo-girling, the balloon penises, the everything, it was all waved away as girls being girls, a bacchanal of the stupid, like oblations for a twenty-first-century neon Dionysus.

Julie really liked bachelorette parties, which, in part, was why she was so pissed.

“Okay. There are two ways we can do this. My way, or—”

“Please don’t fucking say it,” the thing slurred.

“—the wrong way.”

Blood gouted from the stump of the bride-to-be’s raised arm: a stinking ooze of red syrup, far thicker than it should have been, with fist-size clots and nearly black. The other reason all this needled Julie so much was she liked the NoMad speakeasy, liked its pressed tin ceiling, the expensive slouch of its furnishings, loved the gorgeous brass bathtub which stood as its marquee attraction and was now filling with the putrid slurry. Sure, this wasn’t anywhere she had cause to visit save once an actual paycheck. But it was her spot for feigning any claim to pedigree.

And the demon was fucking it up.

And her toes, through the cut-out velveteen heels she’d borrowed from poor St. Joan—God rest their friendship—were getting wet.

No. Not wet, Julie corrected herself.

Sodden.

She was beginning to regret the emerald dress she’d chosen to wear instead of her usual jeans. In contrast to the elegant dress, her arms were a road map of deep scars, earned over years of work, threaded with what looked like barbed wire. On one arm was a rose tattoo, more thorns than blossoms.

From the bleeding stump, a cephalopodic eye glared at Julie and said, “I didn’t do anything wrong.”

Julie could see a tongue flicker in its oblong pupil and a rime of teeth inside the dark—teeth so small they looked like salt grains in the dim bronze lighting.

“You’re in possession of a human body.”

“I am borrowing it.”

“Does she know she’s on loan?”

The woman gibbered, eyes rolled back to the whites. Julie suspected she was beautiful when not drenched in gore, rictused face sheened in sweat, tongue lolling. She was runway-scrawny and cornfed-white. Legs for days. Delicate ankles, ankles now hooked around Julie’s waist. Her knees banged on the rim of the bathtub. Taffeta was everywhere, soaked through with red. She—thefuck was her name? Ally? Alice? Some permutation of that, Julie was sure—moaned, soft and low and terrified.

“No,” said the demon, sullen.

“In that case, it sounds like, what’s the fucking word for it—?”

“Cohabitation?”

“Criminal possession.”

“No. Wait. That’s when you have something like—hold on.” A frisson of tumors ran circuits under the skin of the bride’s pale throat. Up and down. Up and down. Julie memorized the intervals, the specific count of the pebbling, not yet ready to commit to the prospect it might matter, but demons liked routines. It had to mean something. “No. I’m right. Criminal possession is when you are in possession of items or property prohibited by law.”

“And the law says,” Julie interrupted, “you don’t fucking borrow a human body unless you have consent.”

“Shit.”

“So, what’s it going to be, asshole? My way or the wrong way?”

There was no answer save for a wet slorp of tissue receding into muscle. The bride sagged, head ricocheting off the edge of the bathtub, the resulting clang eliciting from Julie both a wince and a muttered “fuck” as she fumbled for her oyster knife. It embarrassed Julie sometimes how makeshift her gear was, what with the armories at her peers’ disposal. The stash her ex possessed—fucking Tyler, that charmed prick—had her wanting to pledge to God, any god, so long as it came with a blessing of arms.

But whatever got the job done.

The oyster knife was her latest acquisition: a pretty thing with a voluptuous ebony grip, impossible to differentiate from any other knife in its category save for the faint scabbing of rust along the blade. Under a microscope, the discoloration would be revealed as runic sigils, nothing ascribable to human invention, not unless they did business with Julie’s very specific supplier.

She drove the blade hard into the bride’s elbow and torqued downward, shearing a curl of flesh from the woman’s forearm, hoping to spoon the demon out or, better yet, kill the fucker. (Her fee would require renegotiation, but convenience always came at a cost. Apartment hunting in Manhattan taught her that early.)

As her knife peeled flesh, the room erupted again in screams. Girls ran for the door, slamming into Julie’s wards. Some slipped on the bodily fluids smeared over the floor as they went, and Julie heard people scrabbling to get up, trying, failing—nails and stiletto heels clacking on the tiles, unable to find purchase. She heard a few of the party girls throwing up again. Not that she blamed them. The bride-to-be’s body held an absolute library of stenches and with half the speakeasy’s guests dead, everyone was receiving an education in charnel perfumery.

Julie stared at the flayed tract of arm in her grip.

She’d missed the demon and found something else.

“Huh.”

Eyes, heavily lashed, the same pastel blue as the bride’s own irises, squinted up at her, neatly encysted amid the muscle fibers. They blinked in the glare of the club’s lighting. Scrunching, visibly upset at their exposure.

“What the fuck?” Julie breathed.

Those were human eyes, nothing at all like the demon’s, and there were hundreds of them. Julie wondered how many more laid hidden, asleep and dreaming, eggs in an egg carton. And she thought about the way the demon had traveled the bride’s throat. Like a nervous tic. Like a squid moving along, fertilizing eggs as it went, and—

“What the fuck?” she said again, this time with a note of rising anger. “You turned her into a nursery?”

The eye hatched through the divot of the bride’s right collar bone.

“I didn’t start this.”

“You’re clearly a part of this.”

“Yes, but I didn’t start it.”

“Who cares?” Julie hoisted up the bride’s arm, stabbed a finger at the wound she’d cored out. “This is gross.”

“It’s part of our biological cycle.”

“You’re not biological!”

The screaming worsened. Julie shot a furious look behind her.

“Shut. Up. I am talking here.”

The clamor lowered to a few terrified whispers, then disappeared.

If any of Julie’s youthful illusions had survived her twenties, they were gone now, eaten alive by the realization that in six months she’d be thirty, still with nothing to show but liver damage, debt, and frozen dinners in an icebox that worked only half the year. She knew what she excelled in and what she did not, and the former was a category that did not include getting a room of screaming, whimpering, gin-soaked girls to shut up with such force and completeness.

“What did you do to my daughter’s hand?”

Julie turned to the source of the question. She was an older white woman, in her fifties, petite frame scaled in lace, with a pencil skirt slitting up to a hip bone. Leather gloves over thin hands, the material polished to a shine. She wore fishnets, stripper pumps, and to Julie’s senses, she was a cut-out paper doll of nothing at all.

“What the hell?” said Julie.

Her hair was blond, brilliantined: a gamine look that flattered her softly creased features. Unlike Julie’s, which was short, spiky, and black, always looking as though it’d been impatiently sawed into shape.

“You cut off her hand.”

“I didn’t.” Julie had, in fact, not. “But what I want to know is who the fuck are you?” She frowned. “And more importantly, what the fuck are you?”

The woman sighed like someone used to sighing when she didn’t get her way immediately. “My name is Marie Betancourt. I’m the mother of the bride.”

Julie raked a look down the new arrival.

Had the woman been in the restroom? Ensconced in a booth with a much younger man? At the bar, commiserating with other grownups? Had Julie, doing lines with the bachelorette party, somehow failed to notice the woman? No. That didn’t make sense. Not with that aura of Marie’s, or rather the lack thereof, the physicality of said void possessing the same gravitational pull as the site of a missing tooth. No, no way some cheap drugs could occlude such weirdness from notice.

“Monster of the bride, you mean,” said Julie.

Marie shrugged. Her accent was New England old money and a thread of something else, something she’d tried hard to gore out of her voice. “I don’t care about your definitions. What I want to know is what you did to my daughter’s hand.”

“What your family hired me to do.”

“We didn’t hire you to disfigure my child.”

“Sometimes,” said Julie, wiping blood from her cheek with the back of her hand, “shit happens.”

Julie gave the room a quick once-over, taking note of how the girls had clumped along one wall and the speakeasy staff were again in view, arrayed behind the bar. Each and every one of them had on the same posture, the same lights-on-but-no-one’s-home stare. So, Marie worked magic too. But what kind? With the woman’s old money pedigree, Julie’s first guess was satanic. She rescinded the thought a moment later. The anarchic catechisms of the Church of Satan didn’t seem like they’d fly with someone from the suburban oligarchy. Something darker, then. Much darker.

The woman said, “Whatever the case might be, get him out of my daughter and then we will renegotiate your fee. You did an ungodly amount of damage to my poor girl, and—”

“Wait, wait, wait. Let me get this straight. Did you say ‘him’? Specifically?”

“I did,” said Marie, crossing her arms.

“Just ‘him’?” said Julie. “There are eggs in here, Marie.”

Her voice was even. “Those are meant to be there.”

“Like fuck they are.”

Marie’s expression creped. “Did you not read the contract you were sent? I thought it was very clear. We need him out. Just. Him. Why is that so hard to understand?”

“Because your daughter is infested with—with—I don’t even know what the hell they are but I sure as hell know I’d dig them out with a garden trowel if they were inside me and I didn’t have anything else to get them out with.”

“For god’s sake, do what you’re paid to do and stop talking so much.”

It hit her then. Oh, Julie thought, as the pieces mosaiced into place.

“It’s like when the neighbor’s shelter mutt won’t stop trying to fuck your pedigree poodle, isn’t it? You’re pissed because it’s not the right dog. You—you’re breeding something in there. You’re using your daughter as an incubator.”

“Perhaps.” And there was the snap, the façade popped. “All right. Yes. One girl in every generation is honored as the Womb, and I’ll be damned if my daughter will breed our family a litter of rejects.”

“Hey,” said the demon.

Both Julie and Marie ignored it.

“Is she going to survive this?” said Julie, suddenly tired.

Marie pinched the bridge of her nose.

“Survive what?”

“Being the goddamn Womb.”

“Maybe,” said Marie. “And if she doesn’t, a part of her will live on in some way.”

Julie stared down at the bride, coddled like an egg herself in the bathtub, limbs everywhere, and she felt pity: a sharp, wretched twang of sympathy. She’d been impressed with how hard the bride had gone, how much she’d drank, the way she kept up with Julie, snorting coke and dropping ecstasy, like it was nothing, like someone intent on living out her last day of being free.

“Jesus, you big money shits can’t help being garbage, can you? She knew she wouldn’t make it. Your daughter knew. That’s why she went from zero to crazy the moment she got here.” Julie smoothed the lank blond hair from the bride’s face. Under her fingers, the woman’s skin burned. “Did she even consent to this? Was she awake when you got her pregnant with . . . whatever the hell this is?”

“She consented to the rite,” said Marie with care, the precision of her statement more telling than a confession. “As for the drugs, she’d always had a problem with them. It’s why we were so pleased when she was made the new Womb. Finally, her useless existence was going to amount to something.”

“This is your daughter you’re talking about.”

Marie shrugged. “And none of this is your problem. I—damnit, he’s trying to find the rest of her eggs. Get rid of it now, or you’re not getting paid.”

The right thing to do, Julie knew, was to say no. The right thing was to tell Marie to fuck herself, save the girl, walk away, and burn the speakeasy down behind them. But the problem with the right thing was it didn’t keep the lights on.

“Stay out of my way, old lady.”

Julie spat a spell so filthy it leaked black ichor over her chin. Her jaw whined with the magic. It thumped through her skull, and up along every tooth, until Julie’s head was a haze of shrapnel and static. Some people had it easy: they carried spells like a girl’s trust in her mother, kept them chambered with no effort whatsoever. Julie wasn’t one of them. She needed them stitched through the fatty part just under her skin. Otherwise, they washed away.

As the glyph-bindings snapped, one after another, wire fluttering from her wrists, Julie found her anger burning even hotter. She couldn’t believe it. Here she was, unbuttoning the barbs of a spell from her skin and for what? The cable bill, last month’s rent, a half-decent dinner if she skimmed from the first. Was she really stooping this fucking low?

The spell burrowed into the bride’s shoulder, cauterizing the flesh as it wormed inside, leaving an inch-wide hole in its wake, and for a second, as the pain in her head blurred her vision into an oily smear, Julie thought she saw the meaty curl of a slug’s tail flick and vanish into the wound. She knuckled the tears from her eyes, leaning back, tongue rinded with a sugar coating of something sour-sweet. As she did, the bride jackknifed up, as though impaled on a hook scythed through her diaphragm—and she banshee-screamed.

Loud enough to make Julie clap her hands over her ears. Hard enough that Julie heard the women’s larynx tear: the screaming becoming graveled, turning wet. Her wailing didn’t stop as convulsions billowed through her. The bride screamed and she would not stop.

Until, with a damp burst—

Her throat split. From the vulvic-like opening, the demon fell, splashing into the puddled gore at Julie’s feet. It resembled a liver fringed with blue-red nerves and overgrown with tumors: little cauliflower protrusions, each of which, at its puckered heart, contained an eye gone dead and filmed with pus. The sight brought Julie no pleasure. At most, she felt an embarrassed relief. She was glad the awful affair was over and sorry about her involvement, and the fact she was both these things pissed her off.

The bride’s throat closed and she swooned again, but this time, Julie caught her before her head could bounce on the tub’s copper rim, held her suspended like the two were modeling for a painting: a hand under the small of the bride’s back, the other beneath the bowl of her skull.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered.

“Finally,” said Marie. “You should have pulled that thing out when it started. If you had, we wouldn’t have wasted so much time.”

Julie set the bride down into the bathtub, arranging her arms so she looked like a saint laid out for display. Her expression was beatific, no longer strained. At rest, if not for long, not with her mother waiting.

“That spell cost way more than you were paying me.”

“You should have negotiated your costs into your original fee, then.”

“Yeah, yeah. Fucking pay me. A grand and not a penny less.”

Marie tossed a handful of bills.

“The fuck. Was that. For.”

Julie collected the money and counted the blood-stained bills, once and then again, irritation kindling. She had hoped for a different outcome but it was as she thought.

“This isn’t what we agreed on.”

It wasn’t even close. Six hundred in soggy Franklins. Julie suspected Marie carried wads of fuck-you money, meant for use in these exact circumstances. Enough that she didn’t look like a crook, but never enough to actually pay up. They were as much statement as her lacquered finger-wave hair, her carriage, her accent and the precision of her diction. Meant to show the gulf between Marie and the rest of the world. Here she stood on a rung next to the stairs and down below was everyone else, rutting in the mud.

“Be glad you’re even getting paid. You fucking mutilated my girl.”

Julie donned a sunny grin.

“Are you sure this is all you have for me?”

“It’s more than you deserve.”

Wiping her filthy hands on her jacket, Julie said, “You know, the problem with the service industry is you have to do everything you can to make sure the customers tip. No matter how screwed up they are, how much they fuck with you, how little they give a shit about your sense of basic human dignity, you have to smile and smile and make sure they have a good time.”

She clambered out of the bathtub, wringing blood from the hem of her pretty, pale green satin slip. She wiped her fingers along the rumpled material, leaving streaks. Paused. In an afterthought, she removed her heels and strung them along the hook of two curved fingers. Briefly, Julie wondered how she looked in Marie’s eyes: gore-splattered, her dress ruined, bare feet, rat-nest hair, a strappy little handbag made to resemble a child’s idea of a stegosaurus.

Good.

“Here’s the thing.”

She approached Marie in a lazy slink, grin widening.

“I’m not your fucking waitress.”

Julie popped open the latch of her handbag. Fingers—long, gray, with far too many knuckles—pushed out from the top, stretching out spider-like.

“You’ve got a nice face, Marie. A model’s face. Cheekbones for days. Nice shoulders too. What do they call it? Fine-boned? Bird-boned? Something pretty like that.”

She slowly approached the woman, holding the handbag just tightly enough that the fingers couldn’t escape, but loose enough for them to grasp desperately at the air.

“You know, back in the Victorian days, some idiot rich bitches—likeyou—would have a couple of ribs removed so they’d fit their corsets better. Creepy, huh? Still. It was fashionable.”

Julie kept approaching until Marie’s back was pressed against a pillar at the side of the room.

“Of course, those Victorian surgeons were butchers. Amateurs at bone removal.”

Julie held up her bag.

By then, Marie realized what was happening.

By then, it was too late.

“I always say, when you want to rip out a bone or two or a hundred, leave it to the professionals.”

She opened her bag and something leapt out, all fingers and teeth and high-pitched screeches like a bat.

Julie took her lipstick from the bag and reapplied it where it had rubbed off, slowly, languidly.

Marie screamed and tried to run. Julie turned to leave, knowing that the woman didn’t stand a chance.

She heard the first crunch just as she reached the door.

TWO

To blow off steam, Julie walked barefoot through the East Village all the way to Chinatown with St. Joan’s ruined pumps dangling from one crooked finger. That sucked, she thought. She needed time to unwind. That really sucked, Julie thought, as she finished a cigarette, leaning against the wall of a head shop, careful to avoid the piss stain sprayed over one corner.

At a glance, Julie was mostly your stereotypical white girl: the oversized eyes made her resemble a knock-off Margot Robbie, but her features hinted at the Korean grandmother who she rarely saw now that she was an adult and could not be bodily dragged to church. Half because the old woman lived so far away, and half because—in her Catholic zeal—she never quite forgave Julie’s mother for shacking up with the pretty blond piece of shit who took off shortly after Julie’s birth.

She liked Chinatown. Most nights, it was more tourists than locals, the latter aware that if you wanted real Asian food you went to Flushing where the grandmothers held court, watched over by what few dragons survived their migration to America. But tourists—even if they walked too slow, even if they clogged the pavements and wore their fanny packs like an invitation—were as much New York as everyone who lived here. The city wouldn’t be the same if there weren’t people to scream I’m walking here at.

Cigarette pinched in the corner of a grimace, Julie flexed her left arm. There was a smiley face sloppily tattooed there, its lower half dissolving into industrial waste. It was ugly, but all her tattoos were ugly: the only tattoo artist she could afford to do spellwork for her also hated her. Not that it was Julie’s fault. She had no idea the sunken-eyed guitarist she’d slept with was the woman’s boyfriend.

People like Julie didn’t get to be choosy. She winced as the spell began to work, the tattoo diluting, spreading over her skin until the entirety of her forearm was a palette of new bruises: yellow, with smudges of green and blue. It hurt, but this was how things went: a lesser agony paid for the removal of a worse one.

Julie gritted her teeth until she lost the urge to idly crush cars parked too near or too far from the curb or, better yet, to do it to their owners. She smoked and breathed and relaxed by degrees as blood pooled under St. Joan’s sopping shoes.

When she felt somewhat human again, Julie joined the throng heading underground to the A line. At the turnstiles where commuters tapped their credit cards to get to the platform, Julie ran her nails over the reader and the bar unlocked for her. If anyone noticed, they kept their mouth shut. Likewise, no one met her eyes or said a word about the blood in her hair or the viscera caking her clothes during the half hour ride uptown. It might have been magic, but more likely it was New York indifference working in her favor. No one in the city gave a damn if you didn’t give a shit yourself.

Up she went and out of the subway again, weaving between twentysomething tech workers still too broke for Williamsburg, a flotilla of exhausted moms and their kids; retail staff staggering home for a two-hour nap before their next shift; tourists intent on seeing the “real New York,” gangbangers, middle-aged drunks, poets, actors, and hipsters looking to rent in what would hopefully be the next big thing.

Julie lived in a ramshackle four-story brownstone on 137th Street. Her apartment, at the far end of the hall on the first floor, was easy to spot for the delivery drivers who bought her food or—moreoften—the mind-obliterating drugs she loved so much. Her front door was slathered from top to bottom with a chaos of crosses, angelic and demonic sigils, gris-gris talismans, milagros, a vellum Seal of Solomon, tomb rubbings, and small idols of gods living, deceased, and mostly forgotten. Her neighbors seldom spoke to her, except for the meth head on the third floor who once tried selling her a bag of speed that was really baby laxative and strychnine. She didn’t even bother using magic on him. She just pushed him down all three flights of stairs until one of his legs bent the wrong way. It was satisfying at the time, but not as satisfying as the speed would have been.

Inside her apartment, Julie slammed the door shut and stripped in the living room, the skylight more than enough illumination to stumble by. She stuffed her clothes into the special hamper reserved for anything that had been soiled or damaged during a job. It was St. Joan’s suggestion. Something to do with accounting, depreciation, and taxes. Julie had never paid taxes but did what she was told because St. Joan was older, wiser, owned the building, and took Julie at her word when she said the rent was coming, just a little late.

Julie stepped into the shower and turned the water up until it was as hot—thank god for small blessings—as she could stand. She didn’t bother washing at first. She stood under the steady, scalding stream, letting it carry away as much of the bachelorette party gore as was possible. Little red clots of something turned the water pink. Julie had a suspicion they’d result in a clog in the drain but that was tomorrow’s problem. Today, she was too tired.

She reached behind the shampoo and conditioner—also St. Joan’s, donated to Julie in the name of pity—for the pint bottle of vodka she kept there for shower “emergencies.” She took swigs as she sponged and scrubbed until both she and the bottle were finished. A little tipsy, she stepped carefully from the tub into soft white slippers with rabbit ears on top. Wrapping herself in a fuzzy robe, she went back to the living room with every intention of lying down—until she got a look at the place.

The coffee table and floor were scattered with food cartons, dirty clothes, half-finished beer bottles, opened bags of potato chips, and drug paraphernalia.

“Fuck,” said Julie. It seemed a good enough summary.

At times like this, she had a quick but thorough system for dealing. Julie grabbed a 30-gallon trash bag from the little kitchen and started throwing everything inside. Food wrappers, empty tins of THC edibles, liquor bottles, ripped bras. Anything she found offensive, anything that brought a frisson of self-loathing, no matter how small: it was gone, gone, fucking gone. It was a wasteful system, she knew—there was always a shortage of underwear—but it was simple and efficient, which is how she liked things.

Simple and efficient.

Not like how life was going to be for the bride.

The Womb, her mother had called her.

When she was done, Julie tossed the bag by the front door and stood there, shaking her head. Even clean and full of vodka, she could still hear the bride screaming as the thing tunneled inside her. She couldn’t stop thinking of the woman and what might happen after, if her family would find her, would walk her right back into their ancestral home—it was always a manor, some fifteen-bedroom atrocity in the suburbs or, if she was really unlucky, somewhere on Long Island, which was technically New York but no one liked admitting such—where she’d have to sit in the dark and wait for the right demons to come breed inside her veins.

Julie exhaled.

It was going to take more than a couple of drinks to clear her head.

She flopped down onto her expensive designer sofa, a leftover from a bad affair she had with someone who thought he was too good for her. Surveilling her apartment, taking in the rank squalor, Julie wondered if he might have been right. Maybe she was trash.

Though she’d cleared away almost everything from the low coffee table, Julie had left the essentials: a bottle of really good vodka, her go-to vice when she was alone; the nearly empty mints tin that held her dwindling supply of cocaine; a plastic baggie with mushrooms and the stale pot brownie someone had left after a party; an empty pack of Sherman Fantasia cigarettes which held hits of molly and Norco.

And a small jade box filthy with dragons. Her most prized stash lived in here. These powders and pills weren’t available on the street. You couldn’t buy them for love or a fuck with every seraphim named in the good book. You had to know someone at Club La Pegre, the clandestine bar behind Billy Starkweather’s bookstore in the Bowery. Julie poked a finger into the box, looking for her favorites. Hookland was an old standby: it gave you visions of all your possible deaths, letting you experience the end as many times as you wanted so you could puzzle out escape strategies. There were Power Puffs too, which turned the world rubbery and Technicolor and fun.

Tonight, though, was a night for a tab of Colors, which granted the user a powerful but temporary form of synesthesia. Julie washed the Colors down with vodka and a tiny line of coke and thought about food, hopeful the synesthesia would manifest as some gustatory malfunction. She was ravenous. Both for food and for some way to distract from the excitement of the day.

Usually, that meant stopping by the 24-hour deli down the street and filling a few cartons with goodies from the steam table. But that would involve getting up again and the food there bordered on healthy. No, she needed grease. She needed the kind of repast that would make cardiologists openly weep. She needed a soaked-in-yesterday’s-frying-oil, each-bite-is-raw-cholesterol kind of meal. Before the drugs took hold, Julie got on the phone and ordered boneless fried chicken drowned in cheese, tteokbokki rice cakes, plum powder–dusted sweet potato fries, and some soju, from the Korean place around the corner.

When she was done, she put on Wolf Totem by The Hu, her favorite Mongolian metal band. With the Colors in her system, the music soon took on texture. Actual texture. It molded around her; a sensation like the scratch of good wool over her bare skin, like hands cupping her chin. What she loved best was the way the bass tolled through her; she felt like a cathedral bell, like a call to prayer, to war, to faith. Nothing human left to her, only sound and the sensation.

No memory of the Womb lolling in her arms, hoping she’d be dead of good cocaine before she was whisked away to the dark.

Powerful as that tab of Colors was, it wasn’t potent enough to distract Julie from the fact that it was closing on the end of the month and there was rent she hadn’t made. Thank all the demons in existence St. Joan was her landlord. Anyone else and Julie would have been out on the streets long ago.

St. Joan, as far as Julie was concerned, was better than any saint in any of the books, be it the Bible or its many torrid cousins. The previous tenant in Julie’s apartment had been there since the fifties and thanks to rent control paid a paltry sum for her impressively spacious accommodations. When Julie asked to move in, St. Joan looked at her like a lost puppy and let her do so without a deposit. In the four years since then, the rent had stayed exactly the same. It was the only thing that allowed her to remain in New York.

It pissed Julie off that she couldn’t just hand St. Joan her money every month on the first. It was, in fact, humiliating, which was the worst part. In a fair universe, fifties-era rent would have been easy. It would have been more than easy. It would have been reflexive. But she didn’t live in that ideal world and since Marie had stiffed her a good portion of her fee, this was absolutely going to be one of those bad months.

Julie fumbled for her phone and ran through her voicemails, hoping for some job offers. But it was all bill collectors, telemarketers, and Dead Air wanting to play video games later that night.

No millionaires come courting. No exes hoping to win her back with a grand gesture. No shy widows hoping to speak to dead spouses, no soccer moms praying Julie could stop questions about why the walls sounded like Daddy begging for someone to let him out, god please.

Julie ran her tongue over chapped lips. Between the bachelorette party and the ridiculous hole she’d dug for her life, she felt herself beginning to spiral somewhere unpleasant. She couldn’t let herself wallow, though. Not now. Not if she was going to make some calls and scare up work. She did a couple more small lines of coke—you’dhave money for rent if you weren’t such an addict, hissed her last reserves of common sense—and settled back into the music, letting it wash over and through her.

For a moment, she considered calling Tyler and begging him for a gig. He worked for Thorne & Dirk, which was technically a law firm, but that was just a minute part of their business. They were mainly an investment company like any other investment company on Wall Street, except for the fact that the majority of their fortune didn’t come from cash or stocks, but from their more exotic investments: human souls, body parts, deals with preternatural gods, curses, the lifting of curses, demonic possessions, and murder of the human and inhuman variety.

Tyler had been the one who had given her the too-expensive sofa just before walking out and leaving her behind for Wall Street and the kind of money and life Julie didn’t dare to even dream about.

No, begging Tyler for crumbs was too fucking depressing. Julie was lacking in options and shortchanged in the pride apartment, but she’d be damned if she’d go crawling to Tyler after what he did—taking credit for some of the hardest, most dangerous jobs she’d ever completed. Forget the assholery, the stringing-her-along, the abandonment. Those she could roll with. The credit thing, though? Hell no. Julie would never forgive him for that.

Or for leaving her behind.

Just one more piece of Manhattan trash waiting to be washed away in the next hard rain.

She thought, I really have to turn my life around. And right away. Starting tomorrow, no more drinking or drugs. I’ll go through my whole address book and call everyone. Someone will have something. Someone always has dirty work they don’t want to do.

There were always solutions. As she told herself this, the cocaine broke through her dread. Julie relaxed into her good mood. By the time her food arrived, she was almost happy. But her geniality was short-lived. As she closed the door on the delivery guy, her upstairs neighbors began their nightly theatrics. There was screaming and crying. The sound of furniture breaking. Crockery being shattered on the walls, the floor, anything with an edge hard enough to crack ceramic.

Every night was the same and every night Julie had to fight down the desire to fix the problem once and for all. Maybe get Kafka on their asses and turn them into roaches, except then the building would have bugs and St. Joan would hate that. For ethical reasons, murder was out of the question, but she often contemplated wrapping a binding spell around the whole apartment and translocating the building to another plane of existence. Only then there would be no more apartment and no tenants to pay their rent, something Julie suspected would upset St. Joan.

And that was the last thing she wanted to happen.

St. Joan was the closest thing to a mother she would admit to. So, she kept her magic to herself and ate her greasy food, sinking deeper into Tyler’s sofa and the tactile pleasures of the music.

Her tab of Colors lasted longer than it usually did. Julie was still high at midnight. When her phone trilled, her world went velveteen and violet. Julie was stoned enough it took a minute for her to recognize the noise for it was: Dead Air’s ringtone. Belly full and coming down from her chemical cocktail, Julie clawed off the sofa and went to her computer. She donned her headphones, tweaked her VPN, and fired up Burning Inside, the battle royale that Dead Air was currently obsessed with.

“Julie!” he shouted into her ears the moment she logged on. “Where the hell have you been? I had to solo my last few matches. You had me playing with pick-ups. Pick-ups!”

“Couldn’t you get Them to play with you?” Julie drawled before she could catch herself.

She heard Dead Air suck in air between his teeth on the other end of the call. He was slightly younger than Julie, twenty-four or so, a Harvard dropout who lived alone in a shiny penthouse overlooking the New York Stock Exchange in the Financial District. When he and Julie first met, she had been convinced he was the scion of a billionaire magnate who’d decided poverty was a fashionable aesthetic.

Except surprisingly, he wasn’t.

Dead Air belonged to what he would only call Them, a pantheon of nebulous somethings ruling over various microcosms of modern technology. Like gods but without an appetite for worship or any want for a clergy outside of Dead Air. To Julie, it had felt like a lot: one priest for a whole digital heaven. Dead Air didn’t seem to mind and more importantly, seemed disinclined to dissect his relationship with Them. Given how hard it was for Julie to keep friends, she kept her mouth largely shut, and tried fastidiously to ignore how the light from his devices sometimes reflected faces in his dark hair.

“They don’t play games,” said Dead Air, sighing gustily. “I told you before. Come on, how many times do I have to explain it? They’re Creator-level entities. They don’t do games.”

“But they can get pissed off at people.”

“You said it wrong. It’s They,” corrected Dead Air. His avatar—a pink-stained knock-off Easter Bunny with a trail of blood wetting the right side of its grinning mouth—ran circles through the lobby as they waited for a new match to start.

“Okay. Geez.”

Another sigh. “By the way, They said to tell you that you can automate your rent payment. You’ve been late—”

“I know how many times I’ve been late.”

“St. Joan—”

“St. Joan will get her rent when I have her goddamned rent. Can we please not fucking talk about my inadequacies?”

Every character on-screen, NPC or otherwise, paused in their circuits to glare Julie. Even her own avatar gawked at her. Their accusation lanced through her screen. The hairs along Julie’s arms and up the back of her neck rose under the attention. Julie had forgotten the first thing that Dead Air had taught about her about Them:

They were everywhere. Plus, she’d been rude. Mean and rude.

“Sorry, Dead Boy,” said Julie. Had she been more sober and less exhausted by the world, she might have had a wisecrack to volley, but Julie was wrung dry, worn to the core of her marrow. She felt grayed out even with the cocaine incandescing through her veins: she felt unbearably mortal, frangible, and so very small. “It was a really hard day. I thought I had a little chaperoning job. But then there was blood and ancient family rituals and a fucking demon squid thing.”

The tension wicked from Dead Air’s voice as the game returned to normal, the characters jerkily easing into their animation loops. “Demon squid?”

“Yep,” said Julie, attention moving to her loadout. Tonight felt like an evening for missile launchers. “It was polite, though. The host’s mom, on the other hand, was a piece of work. She stiffed me on my fee.”

The lobby filled with other players. “After making you go up against demon squid?”

“Yep,” said Julie again, coercing a bravado she didn’t feel into her voice. Demon squid was a funny phrase; it was easy to stitch into conversation, even easier to transform into a joke. So much better than the truth that the girl was probably sitting alone right now, waiting to be wedded to the dark. “Fucking demon squid.”

“Wow. Did you kill the mom?”

Julie frowned a little, heat prickling across her skin. “Why would that be your first guess?”

“Because you’re you.”

“Hmm.” It took her a minute but she realized then what that warmth was: embarrassment. Julie was embarrassed. Muddled by the cocaine and vodka, it took her slightly longer to establish why she was embarrassed and when she did, Julie couldn’t help but choke out a bitter, entirely humorless laugh. Despite how she’d spent the last decade curating a reputation as a badass, Julie was ashamed that Dead Air thought of her as a killer first and foremost: someone who resorted to murder before any rational methods of resolution.

The problem was he wasn’t entirely wrong and she wore the truth of this as endless scars. She was more keloid growth than skin. Her belly was cragged with deep slashes from when a pack of werewolves had torn at her, had dug and dug until the oily ropes of her guts went everywhere; her back somehow an even more impressive mess, mangled with bullet wounds and worse. There were places on her body so dense with cicatrices, the nerve damage so extensive, they could be burned until they were scorched and smoking without Julie feeling anything at all.

All of it was because Julie fought like a grenade blast, a last resort.

But she wasn’t a killer, not in the way she knew Dead Air meant.

At least, she didn’t think so.

She hoped not.

Quietly she said, “Maybe I need to change that. Soften my rep a little. Go more mainstream.”

“Don’t. I like you as you are.” Dead Air gave a small whoop as a match finally began, and then: “Did you kill her, though? Sounds like she deserved it.”

Dead Air carried in him a very specific welter of bloodthirstiness at odds with the rest of his personality. He wasn’t a gorehound, for which Julie would always be glad. She couldn’t abide sadists, at least those who preferred their pain nonconsensually sourced: the other kind was more than fine (and, often, fine in the colloquial sense). Dead Air flinched from any detail of a violent situation, but he always wanted the abstract: the who, the how many, and the what was used.

“She did. But no.”

“Aww.”

She could hear his disappointment. “But I did leave her to dance with a hungry Verdigris. He probably did the job.”

“Yeah,” said Dead Air after a minute, slaked. “Good riddance.”

The greasy food she’d hoovered up was beginning to make her head feel heavy. It was becoming hard to focus, hard to think about the symbiotic connection between fingers and keyboard and moving figures on the screen. Julie had to fight to remember she couldn’t just think at her avatar to make it do what she wanted, the world unspooling into fleece.

After a couple of minutes, Dead Air said: “Julie? You there?”

She heard mumbling. Impossibly, there was a T-Rex in a biplane on a strafing run, gibbing the other players. The ground was a porridge of offal and disconnected limbs, and Julie almost wanted to laugh at how the latter had accumulated, a veritable cornfield of bloodied arms stretched to the indifferent sky. No one was running anymore. The chat was clogged with accusations of hacking and dismayed commands for whoever was doing this to stop. Dead Air’s laughter rose over it all.

“Yo, Julie. Check out this dinosaur. You want a go next?”

Her tongue wouldn’t move. It stayed wadded and heavy in her mouth.

“Please tell me you didn’t fall asleep again.”

Silence.

“Are you for real?” said Dead Air. “You owe me for this. If I go back down to Platinum, that T-Rex is eating you next time.”

Julie staggered up and back to the sofa where she collapsed into immediate unconsciousness. She dreamed of punching Marie in the face. Instead of teeth falling from her mouth, each time she hit her, a wad of hundreds hit the floor. Julie slapped the Mother of the Year around all night long.

THREE

The floor of the rooftop meeting room was perpetually damp with a substance that the firm didn’t want contaminating the rest of the building, although what that substance was exactly, no one in the company was able or willing to say. Anyone making use of the room was required to put disposable booties over their shoes and then deposit them in the incinerator chute on the way out.

Tyler Banks was Thorne & Dirk’s head of Client Excisions, meaning he made problems disappear. Cut them entirely out of existence when necessary. However, he didn’t like getting his hands dirty with the seriously dangerous jobs. That’s what Julie was for—but she was the last thing on his mind as he stepped into the room.

Inside, the space smelled like the ocean at low tide: brine and sulfurous rot and things that did not belong on the shore. Bathyal things, deep water stuff, things Tyler desperately hoped would stay forever uninterested in the land.

He put on his booties and exchanged nods with the early arrivals.

There were old-fashioned fluorescent lights overhead, and something about their glow drained everything and everyone in the room of color, left them, if not exactly so, then very close to the warm infected white of a purulent wound. Occasionally, a bulb would pop, and the shadows rearranged themselves in unpleasant ways. The floor was tile and there were body-size refrigerator compartments lining the wall opposite where Tyler stood. No one at Tyler’s pay grade knew what was in them.

Every surface was inscribed with ancient runes and symbols so obscure that only a few of the senior members of the firm could read them. The ceiling seethed with black chains. Large slaughterhouse hooks hung from the links at narrow intervals. Most of the time, they were there to hold various ceremonial vessels, but Tyler had seen them used for different purposes.

Considering its primary function, the room was tidy, which Tyler respected: the complete opposite of the other Shift Rooms and resurrection chambers in the building. There were no spooky candles or cobwebs. No altars heaped with human bones. This was a serious setting for serious people and—smellnotwithstanding—Tyler quite liked the professionalism of the space.

He took his customary spot between Johnson Andrews from Recruiting and Annabeth Fall from Internal Security. Fall looked worse for wear: unsurprising, given how her department used its junior staff as living batteries. That Fall was still here, blanch-skinned and bruise-eyed, was testament to her strength. But she was human and Tyler estimated it would be another three months or so before a discreet ad looking for her replacement would begin circulating.

The last person to enter the room was Clarice Winterson from Surveillance. Always Clarice, he thought irritably. A century of employment didn’t excuse her from basic courtesies like punctuality. Once inside, Clarice pulled the vault-like steel door closed and locked it. Then she and Alan Lansdale from Afflictions went in opposite directions to wheel two twelve-foot-tall Tesla coils to the center of the room, bookending a tall, baroque gold and glass vessel suspended from the ceiling. They fussily secured it to the floor, checking it over, clucking to themselves. Tyler shifted his weight from one foot to another, impatient, as the two traded places, inspecting the other’s thoroughness at anchoring their respective devices.

When they finished, they went to stand at the tails of an Odal rune chiseled into the floor. Tyler and the other members of the meeting did the same, forming a knot of thirteen people.

Clarice looked around the group and said in her seismically low voice, “Put on your equipment.”

Immediately, the assembled executives slipped on the heavy industrial earmuffs and tinted goggles they’d brought with them.

Except for Warren Brautigan from Contracts. He cursed and twisted at his ear cups.

“What’s the problem?” said Clarice.

Brautigan swore again, his voice rising in pitch. “One of the damn side pieces came off my muffs and I can’t get it back on straight. Can I go and get another pair?”

“No,” said Clarice. “The meeting is about to start.”

“It’s going to ruin my hearing.”

Tyler had to suppress a grin. Like everyone else in Contracts, Brautigan was reprehensibly handsome—radioactive blue eyes, cover-model haircut, a jaw square enough to plot on a graph—and unwholesomely aware of the fact: he was indolent in that way the very pretty always seemed to be, convinced he could be spared anything so long as he batted his eyes in the right direction. It brought Tyler a vicious pleasure to see Brautigan so frantic, his cheeks marred with high color. You deserve this, he thought with great satisfaction.

“Good,” said Lansdale. “You should suffer for not checking your fucking gear before you got here. Now shut up and hold the damn things together with your hands.”

Clarice took what resembled a chunky television remote from a jacket pocket and used it to turn off the overhead lights. Tyler knew what was coming. Discreetly, he checked to see if his earmuffs were on straight and waited for their visitor’s big entrance.

After a moment of dead silence, the engines of the enormous Tesla coils droned to life and long million-volt purple arcs of electricity wound their way out from the summits of the two machines. When the edges of those arcs brushed the top of the aureate vessel hanging between them, the liquid inside began to swirl and darken, corkscrewing into a whirlpool, the violence of the momentum such that the container began to shake.

Though Tyler had the appropriate ear protection, the sound remained deafening. His hair grew buoyant from the static, lifting straight out of its helmet of pomade. All the precautions in the world and the collateral effects still hurt. The ritual was always a reminder of what a helpless sack of meat he was and how the simplest mistake in the meeting room could snuff him out completely. The only thing that gave Tyler comfort was the pleasing spectacle of Brautigan cowering and squirming, hands clamped ineffectually to either side of his head, blood leaking in strands down the trunk of his throat, every vein in hard relief.

When the water had darkened to a lightless black, not so much a color as an eye-watering void, a tendril wormed into view. It bobbed thoughtfully for a few seconds, as if measuring a spread of options, a searing oxygenated pink against the jet-black nothing, like a good steak cooked to medium rareness, the incongruous vividity setting Tyler’s teeth on edge. Then the tip curled, and it knocked thrice on the glass: an abashed-sounding plink plink plink. No one in the thirteen moved, or spoke, or breathed. Even Brautigan froze, his suffering overridden by a limbic certainty that attracting notice would mean immediate annihilation.

The tentacle made another attempt. When no one responded still, it seemed to wilt into the gloom. Tyler braced. He knew what would follow. In the next instant, dozens of tendrils whipped outward from an unseen radix, slamming into the glass, over and over, with increasing violence. Tyler had witnessed the process a hundred times. He knew the vessel wouldn’t break; Thorne & Dirk prided itself on having top-shelf equipment. But still the sight filled him with a neolithic terror.

Soon, the vessel became overgrown with sucker-lined flesh, the tendrils flailing gracelessly over the rim of the glass: the motions of a newborn, disconnected from any experience of the physical world. Dark, now rancid, liquid sheeted onto the floor. Tyler checked that he’d pulled his booties up high enough to protect his expensive Italian loafers from the stuff. Brautigan, still in agony, resumed his tortured dance, soft shoeing a few steps back before slipping, turning almost a hundred and eighty degrees before finding his footing again.

He’s going to wish he fell, thought Tyler. Clarice is going to write him such a report.

Then the creature birthed itself from that bloom of meat with a long, pleased groan of a sigh. Its body was a spiraling lattice of gristle, fervid with grape-like red tumors, some of which erupted as it moved, expelling phlegm and a cancer of stubby embryonic hands. The grasping neoplasms multiplied in number, until the thing was frilled with them, flower-like. At its crown was what resembled a horse’s skull and that too was ravaged by malignancies, pebbly sarcomata fruiting through the joints, the eye sockets. It was the color of the light in the room, the same blighted white.

With the rite complete and their guest fully corporealized in its favorite habitat, the Tesla coils shut down and the fluorescent lights ticked back to life. Around the rune, people removed their earmuffs and goggles, exchanging surreptitious looks with one another: checking, perhaps, to see if any of them had been shaken and could be recategorized as prey. Clarice waited until the group was done with its cruel self-analysis. She raised her arms and everyone followed in an ostentatious bow to the creature before them.

Clarice said, “Welcome, Proctor. We’re honored to have you with us.”

The Proctor’s head remained stationary, but its myriad hands—they were almost translucent, threaded with black capillaries—shivered and groped at the air in Clarice’s direction. They beckoned at her but she stood her ground, her face unyielding. The thing laughed.

When it spoke, its jaws didn’t move. Tyler, like the others, heard the Proctor’s voice inside his head—a sensation he despised. It was such an intimate invasion. Another reminder of his helplessness in the presence of all this power.

“My children. Oh, my child—no, no we’re not there yet, but soon. Welcome, my colleagues then,” said the Proctor in a curiously secretarial voice: pleasing, warm, deferential, female, utterly at odds with its appearance. “Your presence and obeisance fill me with joy.”

“We are honored to have you with us and await whatever tasks you have for us,” said Clarice.

“So many, many tasks. More than there are stars. But first: I ask a question.”

“Yes, Your Grace?”

“Who among you turned their back on me as I arrived?”

All eyes went to Brautigan, and Tyler did not bury his grin.

“It was me, Proctor,” Brautigan said, his voice barely above a whisper. “I’m terribly sorry.”

“Your name, your name. We—I must have a name!”

“Brautigan from Contracts, Your Grace?”

“You gave such offense, Brautigan from Contracts.” It clacked its jaws and Tyler wondered if it was trying to be relatable, if the sound was the Proctor trying to laugh. “You know the law, Brautigan from Contracts. You know what is right and what is our right.”

“I—I didn’t mean to. You know I glory in your existence. You know my eyes are only for you. I am only for you. Please.” Brautigan repeated the word in the hopeless whimper of a beaten child.

The Proctor said nothing at first and then: “What is the law, Brautigan?”

He dropped his gaze to the floor. The light was wrong. It reflected indigo on the skin though there wasn’t a reason for there to be any purple in the room. Everyone looked necrotic, but Brautigan especially. He wasn’t very pretty anymore. “That none may point a weapon or show disrespect to a Proctor.”

“Then you admit to the offense?”

“Yes, but it wasn’t my fault.”

“Fault isn’t the issue. The law is the issue. Thorne & Dirk is a law firm and the law must be obeyed. Otherwise, all is chaos. Do you understand? The law is the point. The law is everything.”

“Y-Your Grace. Please.”

“The law will be obeyed.”

“Please.” It was a scream.

Something shot from the vessel—faster than any of Tyler’s telemetric enchantments could record—and slammed into Brautigan’s face, knocking him back several steps. A gelatinous mass of bloodshot flesh had welded itself to the man’s face. As Tyler watched, the clot of meat feathered into a thousand delicate strands which in turn elongated: growing joints, spewing muscle, thickening until they became broad cables wrapped tight around Brautigan’s head. In seconds, he was engulfed.

Brautigan gave a muffled scream.

He howled and torqued and stumbled and thrashed, clawing at his face. His nails found no purchase. They sank into the flesh glued to his own and stuck there, just for a moment each time, before he could wrench them free. Soon, his struggles began to weaken. It was clear to Tyler and every other witness in attendance that there were no openings in the mask: Brautigan was slowly asphyxiating.

Tyler couldn’t look away.

Brautigan tottered a few steps to his right and then sank onto his knees. His chest heaved as he tried to draw in more air to scream, but the meaty lump only squeezed tighter. Soon, he dropped and lay silently on the wet floor. A hot tungsten light began to radiate through the fat-pocked tumor encysting Brautigan’s head. Tyler thought he could see movement in the rime of tissue matter: something working itself into the man’s mouth and nostrils.

The Proctor said, “Who here represents Afflictions?”

“Me, Your Grace,” replied Lansdale.

Another moment and the Proctor said, “Do your duty, flenser.”

“As you wish, Proctor.”

Tyler’s heart ratcheted in tempo but he kept his breathing even, made sure the burst of adrenaline didn’t reflect in his expression. He knew exactly what the Proctor’s decree meant: torture. The unending kind without even hope for death. Brautigan would only be released when the Proctor returned and pronounced the sentence complete, and who knew when that would be?

“The law has been served. Tasks must now be assigned. Who here represents Excisions?”

Tyler swallowed.

“That would be me, Your Grace,” he said.

“Tyler. Your name is Tyler,” it said, as though his name required memorization. “Yes?”

“Yes, Proctor.”