11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

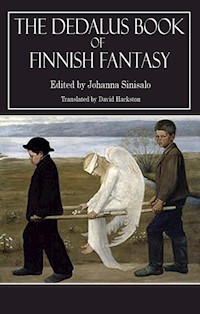

- Herausgeber: Dedalus

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Highly praised anthology of 100 years of Finnish literary fantasy. The latest volume in the Dedalus European fantasy series, this anthology of short stories includes a wide range of texts covering the period from nineteenth century until today. The richness and diversity of the stories reflects the long tradition of fantasy in Finnish literature, ranging from the classics to experimental literature, from satire to horror. This is the first collection of Finnish short stories of its kind and almost all are translated into English for the first time. It includes work by the leading Finnish authors Aino Kallas, Mika Waltari, Arto Paasilinna, Bo Carpelan, Pentti Holappa, and Leena Krohn as well as contributions by the rising stars of Finnish fiction.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

THE EDITOR

Johanna Sinisalo is one of the leading Finnish authors of her generation. She is the author of many highly acclaimed short stories and her first novel Not Before Sundown (called Troll – The Love Story in the USA) won the prestigious Finlandia Prize in 2000 and has been translated into English, Swedish, Japanese, French, Latvian, Czech, German and Polish. The book also won the James Tiptree Jr. Award in the USA in 2005. Her second novel Sankarit was published in Finland in 2003 and transfers the national epic, the Kalevala to the twenty-first century. One of her stories is featured in the anthology.

THE TRANSLATOR

Since graduating from University College London in 1999 David Hackston’s work as a translator has focussed largely on the stage and he has translated Finnish drama for theatres around the UK including the Gate, the Royal Court and the Royal National Theatre. He is a regular contributor to the journals Books from Finland, Swedish Book Review and Nordic Literature. He currently lives in Helsinki where he is working on a thesis dealing with theatre translation. He is also an active composer and viola player.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The editor and translator would like to take this opportunity to thank a number of people whose help has been instrumental in the completion of this book. First and foremost our thanks go to Iris Schwanck and her staff at FILI, the Finnish Literature Information Centre, and the Arts Council of Great Britain for their tireless work and financial support. Thanks go also to Eric Lane and all at Dedalus Books for the opportunity to present this selection of Finnish fantasy writing to the English-speaking world. Our gratitude goes to the featured authors for their comments and advice and to the numerous rights holders for their cooperation. Many thanks to Hannele Branch – a truly inspiring Finnish teacher – and to Emily Jeremiah, Casper Sare and Oliver Wastie for their invaluable comments at various stages of the translation and for their support, moral and otherwise. Finally we would like to express our warm thanks to each other: this project has been a fascinating journey into a world building bridges between languages and cultures, and working on it together has been a true pleasure.

Johanna Sinisalo

David Hackston

For more information on Finnish literature and a link to Books from Finland, a quarterly journal of writing from and about Finland, please visit: www.finlit.fi/fili

CONTENTS

Title

About the Editor and the Translator

Acknowledgements

Introduction by Johanna Sinisalo

Aino Kallas: Wolf Bride (‘Sudenmorsian’, 1928)

Aleksis Kivi: The Legend of the Pale Maiden (‘Tarina kalveasta immestä’, 1870)

Mika Waltari: Island of the Setting Sun (‘Auringonlaskun saari’, 1926)

Bo Carpelan: The Great Yellow Storm (‘Stormen’, 1979)

Pentti Holappa: Boman (‘Boman’, 1959)

Tove Jansson: Shopping (‘Shopping’, 1987)

Erno Paasilinna: Congress (‘Kongressi’, 1970)

Arto Paasilinna: Good Heavens! (‘Herranen aika!’, 1980)

Juhani Peltonen: The Slave Breeder (‘Orjien kasvattaja’, 1965)

Johanna Sinisalo: Transit (‘Transit’, 1988)

Satu Waltari: The Monster (‘Hirviö’, 1964)

Boris Hurtta: A Diseased Man (‘Tautimies’, 2001)

Olli Jalonen: Chronicles of a State (‘Koon aikakirjat’, 2003)

Pasi Jääskeläinen: A Zoo from the Heavens (‘Taivaalta pudonnut eläintarha’, 2000)

Leena Krohn: Datura and Pereat Mundus (1998–2001)

Markku Paasonen: Three Prose Poems (2001)

Sari Peltoniemi: The Golden Apple (‘Kultainen omena’, 2003)

Jouko Sirola: Desk (‘Kirjoituspöytä’, 2003)

Jyrki Vainonen: Blueberries (‘Mustikoita’, 1999)

The Explorer (‘Tutkimusmatkailija’, 2001)

Maarit Verronen: Black Train (‘Musta juna’, 1996)

Basement, Man and Wife (‘Kellarimies ja vaimo’, 1996)

Copyright

Introduction

Literature written in the Finnish language is surprisingly young. Despite the fact that both a thriving folk culture and a highly creative tradition of oral poetry have existed throughout our history, it seems incredible to think that written literature in Finnish has existed for little more than a few centuries. The earliest books written in Finnish, dating from the mid-16th century, were all of a religious nature, and so those who could speak only Finnish had to wait until the 19th century for the publication of secular literature. Finland’s geographical position caught between two great empires created a strange climate in which the national language was subordinated at times to Swedish, at others to Russian, and this in turn resulted in that even the most respected Finnish writers wrote mostly in Swedish – a language which still has official status in Finland and from which many respected writers have appeared and still appear to this day.

The rise of the Finnish language to a ‘real’ and true literary medium only began in earnest at the end of the 19th century. With such a short history it is striking to see how broad and rich the scale of writing and reading in Finland has become today. In a country with little more than five million inhabitants literature is read, bought and borrowed from libraries more than almost anywhere else. Statistically Finns are among the most literate people in the world.

To generalise slightly, one could say that Finnish literature is dominated by the tradition of realism. In Finland realism is widely seen as the correct way to write, whilst other genres are deviations from this norm – some would claim that these deviations do not represent ‘respectable’ literature. All too often one hears the Finnish reader shun works including elements of fantasy on the basis that such things are ‘not true’. The overwhelming strength of the realist canon has made some readers forget the fact that even realistic literature is made up; that it is every bit as fictitious as the most unbridled fantasy literature.

Realistic narrative is solidly anchored in the empirical, in that which can be proven and authenticated, and this is perhaps one of the reasons for its popularity in Finland. We are a small nation with a difficult, broken past. One of the greatest functions of literature in our country has been the depiction of history and human destiny in a form both easily approachable and recognisable; literature has thus become an important part of the Finns’ collective memory.

Still, Finnish literature has given rise to – and, indeed, continues to give rise to – writers who wish to look at the surrounding world through the refracted light of fantasy. It was easy to find dozens upon dozens of authors who have taken bold steps into the realms of surrealism, horror and the grotesque, satire and picaresque, the weird and wonderful, dreams and delusions, the future and a twisted past. Far more difficult, however, was the task of making a final selection from this marvellous and wide-ranging group. This anthology presents the work of twenty authors, though it would have been just as easy to present the work of twice as many authors of the highest calibre.

In making these decisions it was fascinating to note that, regardless of the great respect felt towards realism, the presence of elements of fantasy in a writer’s work has not prevented them from attaining the highest possible status in literary life. Of the twenty authors in this volume, six have received Finland’s most prestigious literary award, the Finlandia Prize, and many others have been shortlisted. Amongst the present authors there are some whose works have already been translated into numerous foreign languages.

In making these decisions I have tried to build up a cross-section of Finnish fantasy, both thematically and chronologically. The oldest texts date from the dawn of our literature, whilst the newest were written within the last few years. In addition to writers with a long and distinguished career behind them, I have also included works by a number of promising young writers.

Once I had whittled the writers down to twenty I assumed that the diversity of the authors would automatically produce a selection of radically different texts. On one level this is indeed the case: the spectrum of styles, subjects and originality represented in these texts is impressive. Yet at the same time I observed that certain distinctly Finnish elements and subjects recur throughout these stories, albeit in a myriad of different ways, but in such a way that we can almost assume that, exceptionally, they comprise a body of imagery central to Finnish fantasy literature.

One of these elements is nature. To this day Finns live in a very sparsely populated country, surrounded by lakes and large expanses of forest. Every Finn appears to have very close, personal ties to nature. In Finland culture and nature do not struggle against one another, they are not mutually exclusive, rather they encroach upon one another, they merge and influence one another. In the present fantasy stories the theme of nature often manifests itself through the very active role given to forests and animals.

Another recurring element is that of war. Throughout the length of its history Finland has lived between two great empires: Sweden to the west, Russia or the Soviet Union to the east. Both have taken turns to conquer our country, and the struggle to maintain our precarious independence has led to wars whose scars are far from healed. Here the theme varies just as much as the treatment of nature: in addition to the many direct references to war, its ghost can be seen in the themes of power, slavery and control, or even as a post-apocalyptic vision.

In any case, it is a joy to present here twenty different voices, each of whom draws open the curtain of reality and offers us a glimpse into their own highly distinctive worlds.

Johanna Sinisalo

Wolf Bride

Aino Kallas

Aino Kallas (1878–1956) is well known as a writer of poetry, short fiction and novels. She spent the majority of her life in Estonia, where she was inspired by local history and folklore from which she drew inspiration for many of her ballad novels. The theme of destructive love is central to all her works and in the novel Wolf Bride (‘Sudenmorsian’, 1928), from which the present extract is taken, she combines the motif of illicit desire with ancient Estonian religious beliefs. As no literature was written in Finnish during the mid-17th century – when events in this novel take place – Kallas’ work constitutes a highly original, creative vision of what such a written language may have been like.

Chapter Four

Yet just as the day has two halves, one governed by the sun and the other by the moon, so there are many who are people of the day and who busy themselves with daytime deeds, whilst others are children of the night, their minds consumed with nocturnal notions; but yet there are some in whom the two merge like the rising of the sun and the moon in a day. And all this shall be known in good time, when Fate thinks it fit.

And so it was that at first no one had a thing to say about Priidik, the woodsman of Suuremõisa, or his young wife Aalo, nor in the mill of chatterers and babblers was there a drop more water than in the island’s rivers during summer-tide. For they lived a quiet life in loving harmony, in amity and accord with the villagers, and like good Christians they went often to church and received Holy Communion, and showed respect and loyalty to the law and to the estate in everything they did. No one spoke ill of Aalo, for she rose early in the morning and was good and gracious, neither rude nor rash nor indignant nor aloof, but good-mannered and in every way as calm and clement as a meadow breeze. Though in sooth many a man was vexed by the pallour of her appearance and the colour of her hair, so like the autumn-rusted juniper it was, though it was cropped short and covered in winter-tide with a woollen hood and in summer-tide with a long and narrow scarf with lace ribbons hanging on both sides upon her shoulders, as befits a wedded woman.

Thus when Priidik the woodsman and his young wife Aalo had been married almost one year Aalo bore their firstborn, a daughter, who was duly baptised in the church at Pühalepa and given the name Piret.

But the Wicked Spirit, who despises peace, had already chosen this bride for his own, just as a lamb is marked out from the flock, and cunningly lay in wait for the moment upon which he could shape her in his image.

For as from the same piece of clay a potter may fashion either a pot or a tile, so the Devil may shape a witch into a wolf or a cat or even a goat, without subtracting from her and without adding to her at all. For this occurs just as clay is first moulded into one, then shaped into another form, for the Devil is a potter and his witches are but clay.

And so it was that in the month of Lide (the villagers’ name for Martius) a great wolf hunt was to be held in Suuremõisa once again, as soon as the ice across the strait of Soela had begun to thin and could no longer bear so much as a wolf’s paw, thus cutting off his only escape.

Indeed, like other public festivities, this event had been planned for many months, and ale and spiced liquor brought for the villagers to the inn at Haavasuo, with bagpipers too, for at the hunting feast there is also much dancing.

And so lookouts were sent to the swamps and to the marshes, and in every village old wolf spears were sharpened and cleaned of their rust.

But it was not only the villagers who waited eagerly for the wolf hunt: Satan’s minions rejoiced too, as this came at a most opportune moment for them.

Thus one morning a lookout, who had been keeping watch from atop a tree, brought news that the wolves had been sighted.

And thus all the men from Kerema, from Värssu and from Hagaste, from Puliste, from Vahtrapää, from Sarve and from Hillikeste were summoned to the hunt, two or three from each and every house, some eight hundred souls, womenfolk and children notwithstanding, and all of Suuremõisa’s woodsmen, with Priidik amongst their number.

Thus a biting, spring day dawned, sunshine melting the snow in parts yet holding still the lowlands in the grip of frost.

When at daybreak Priidik the woodsman arrived at Haavasuo, the inn was thronging with folk as it does on market day, all turned out in their best attire as if for a grand banquet.

Aalo too had come to follow the hunt and the festivities, clad in a loose and wide-sleeved jacket, and beneath this a skirt of lamb-grey, cross-striped and pleated throughout. Though because there still lay frost on the ground she wore upon her head a brown hood, such that is called a karbus, draped with pretty red ribbons. And around her waist hung a belt of brass, made of rattling coins, holding on the one side a knife tethered in a tin sheath and on the other a pin box.

Yet little did she know of the trap set upon her path as she stepped out in all her finery, and that morning she was as gay and graceful as a young doe and her pretty countenance was a joy to behold.

First the spearsmen were sent out with their nets to the hunting ground, they dashed headlong saddled upon their steeds at full gallop, their spears outstretched, like a horde of Cossacks or Kalmyks.

Soon after them left the wolf hunters themselves, known as the loomarahvas, in a great circle around the island of Hiidensaari, hollering at the tops of their voices and firing their muskets, thus to fright the wolves from their hiding places, if indeed they had taken cover amongst the thicket or on the islands upon the swamp.

And thus a great clamour and commotion spread across the boggy lands of Hiidensaari, where ordinarily none but crane and curlew sing, and where the wild wolf howls.

But Priidik the woodsman sped towards their agreed hunting ground upon the vast meadow. At one end there stood a high stone wall, and behind the wall were hunting nets hidden from view.

And so Priidik and the other huntsmen crouched amidst the coppices on either side of the meadow, waiting and making not a sound.

Then all of a sudden there came a warning cry from a blackbird high in the treetops and at that moment, herded by the loomarahvas, the two wolves came into view and the shouts and cries at their heels pealed out. Nor could they hide any longer amongst the thick bushes, for the fierce barking of the hunting dogs quickly spurred them onwards. And so they both began to gallop faster, their jaws open and their dark, ominous tongues dangling low to the ground.

And with that Aalo, wedded wife of Priidik the woodsman, standing amongst the crowd of villagers, looked on as the pursued wolves dashed past her, gripped in the fear of death.

And though at times they were obscured in gunpowder smoke, as shots rained in from behind them and from the sides, Aalo could see that the first of the wolves was smaller in stature, whilst the other was a large, powerful beast, its legs tall and its body long and grey, its muzzle sharp and its forehead wide, its wild, slanted eyes full of the fury of the forest.

Then, all at once, Aalo heard quite distinctly in her ears the words:

‘Aalo, Aalo my lass, will you follow me to the swamp?’

At this she shuddered, as if she had been shot in the side, for she could not see the speaker of these words. But both her body and her soul were shaken by a mighty wind, as if a great force had whisked her from her feet and lifted her into the air and like the finest fowl’s feather spun her in a sacred storm, until she began to gasp for breath and all but swooned upon the spot.

And all this happened faster than a beat of a gull’s wings above the sea.

Once recovered, Aalo saw the first of the wolves, every last fibre of its body strained in gallop, its head and legs and tail forming a single straight line as it leapt headlong twice the height of the stone wall, believing there to be sanctuary and salvation on the other side, though what awaited was in fact a certain death.

But then the larger, more powerful beast, running behind the first, as the men’s eyes were fixed upon its companion, sped off to one side and escaped deep into the forest, thus breaching the men’s barrier.

With this Aalo hurried to the foot of the wall where she saw the wolf struggling in the net, shrouding its body like a cloak, all hope of escape extinguished. And such did this ensnared beast pant as if its sides were about to split, and spittle frothed from its black, foreboding jowls and between its curved fangs as the villagers scathed and scorned it.

And Aalo saw the men with their spears raised aloft, ready to strike deep into the wolf’s side, and amongst their number stood her husband Priidik.

And at that moment she heard those same words once more; fainter, perhaps further off, as if someone had cried from the wilderness, yet she alone could hear:

‘Aalo, Aalo my lass, will you join the wolves at the swamp?’

Like a calling did these words reach her, like a coaxing cry from the swamp.

And thus at that very moment a dæmon entered her and she was possessed.

And this Spirit is called Diabolus sylvarum, the Spirit of the Forest and of the Wolf, whose home is by the swamp and in the wilds; brave and fearless, a spirit of strength and freedom, and yet also of rage and violence; mystified beyond all comprehension, winged like the storm clouds and ablaze like the heart of the earth, yet forever caught in the shackles of Darkness.

But at that same moment Priidik the woodsman thrust his spear through the net and into the side of the thrashing wolf, and many of the other men too, and with that the beast’s blood spurted high into the air.

Yet not even did the dogs dare touch the wolf’s flesh, for it was foul and vile to their throats, and was thrown as carrion to the birds.

And late into the night came the sounds of rejoicing, the wheeze of the bagpipes and the booming of muskets from the inn at Haavasuo, for there, fuelled with ale and spiced liquor, did the villagers celebrate their wolf hunt, and the lads and the maids danced in time.

Chapter Five

O ye witches, ye who before the Incarnation of Our Lord and ever thereafter have celebrated Satan’s Sabbath, who can count your number! Simon in the Holy Bible, Circe and Medea, Caracalla, Nero, Julian the Apostate – all emperors of Rome – and last of all Faust and Scotus! How then could little Aalo of Pühalepa in Hiidenmaa have resisted the Might of Darkness?

And so it was that from the time of the great wolf hunt at Suuremõisa Aalo, wedded wife of Priidik the woodsman, had begun to yearn for the swamp and for the company of wolves; how she longed to leave behind her all humanity and the Christian union into which she had been conjoined at the Holy Font and through a number of other Sacraments. For so strongly did the Spirit stir her which had entered her; like bellows it fanned the flames in her blood, making her obey the command of the Devil and transform herself into a wolf. As evening fell, and in the dusk the wolves began to move closer to the village settlements, so their howl carried in across the wolds and upon the cottage threshold Aalo stopped amid her chores and stared out into the forest, and to her ear their howl sounded as soft as the sweetest music, for she too was a sister of their spirit.

Yet all the while she pleaded with her husband Priidik the woodsman to fasten strong hatches at the barn door and for safety’s sake to place thick iron bars behind them, and she acquired a new and ill-tempered guard dog. Neither did she once allow the shepherd boy to take the cattle beyond the pasture, though in sooth during summer-tide the wolves have other prey than merely cattle, such as hares, foxes, hedgehogs and woodland birds. But this Wolf hungered neither for cows nor sheep nor even for young foals: the body and soul of one young bride was its only prey, for it was an envoy of the Underworld.

And so that spring Aalo took care never to go alone to the swamp or deeper into the woods, for she knew that danger lurked there. As yet she had not wholly forgotten the union of her Christening and the effects of the Holy Water still protected her soul. But such a time did she spend caught between fear and desire, that the fire inside her ripened her, like the sun beating upon wheat in the field, waiting for the hour of its coming.

And throughout this time, as she endured this struggle, her thoughts strayed often to realms of death and darkness, as if she had sensed and forseen her premature, sorrowful demise. For unto her was everything filled with prophecies and omens, from which she divined signs and warnings and applied them to her own plight.

Thus in the mornings she would say to her husband Priidik:

‘The eagle owl was hooting high in the birches last night – what does this foretell?’

Or she might say:

‘Black ants came through the crack in the steps and marched across the threshold – surely this does not bode well.’

However she did not expect an answer to such questions, she merely uttered them to relieve her own anxiety.

But one day she returned from the paddock and said:

‘I saw strange things in the forest today: a Mourning Cloak Butterfly rested upon the yellow sand amongst the junipers. It had black wings, black as the finest cassock of the minister at Pühalepa, but their edges were the golden colour of honey and their spots the blue of the sky. Who now is going to die?’

Yet the Devil’s wicked arrow, which long ago had struck her, slowly clouded her mind with its poison, and the dæmons and their Master rejoiced in Hell, for their prey was entrapped and victory was near.

Thus it transpired that over Midsummer Priidik the woodsman was to leave for Emaste for two days to welcome a firewood merchant ship, and Aalo was to remain at home with their little daughter Piret, an old servant woman and a young shepherd boy.

But the night of the solstice has since pagan times been full of witchcraft, for then the dæmons wander freely and witches carry out their dark deeds under the shadow of night. For upon this night they convene at the crossing of paths and at the meeting of three fences and smear potions upon gates and stable doors and tie the corn in magic knots, reading spells and thus damaging both cattle and crops. And islandfolk say that on Midsummer’s Eve the water sprite Näkki can be seen in the body of a young woman searching for her drowned child.

And so upon this Midsummer’s Eve did the young folk of Suuremõisa and the neighbouring villages make their way to the swings and solstice fires, and the young maidens collected handfuls of nine herbs hoping to dream of their husbands-tobe. And the old too remained awake and kept watch over their houses, ensuring that no one came inside to work spells or cast an evil eye.

But Aalo, wedded wife of Priidik the woodsman, had nowhere to go that evening and sat in the cottage doorway.

And so the evening drew on and the bumble-bees rested in the trees bearing their golden goods, and all were fast asleep: the servant woman in her bed, the child in her cradle, the shepherd boy by the warmth of the stove, just as the handmill, the loom and the fishing nets hung upon their poles, and not so much as a wisp of smoke rose from the outdoor hearth.

Only the linen cloth, which Aalo during winter-tide had woven into strips, lay spread across the grass to whiten and stretched back and forth across the length of the yard like a pale yellow path.

And then, upon the cottage steps, Aalo saw the sun, the eye of the Lord, setting lower and lower in the sky, as low as the berries on the forest floor, then disappearing altogether, and with that evening soon chilled into night.

Then suddenly Aalo’s ears rang again with those same words she had once heard at the wolf hunt:

‘Aalo, Aalo! Aalo my lass, come join the wolves at the swamp!’

But this time they did not sound like a cry or a calling, but like an overwhelming command which had to be obeyed, lead though it may to death and damnation.

No longer could Aalo resist, and thus she dismissed her Holy Union and the fact that Christ our Saviour suffered and died upon the cross for her sins too, just as the people of Israel turned their backs upon God and their redeemer, that brave hero Gideon.

And so she gladly gave up her spirit, her body and her soul to the dæmons and let them lead her onwards.

And not even the whimpering of her innocent child could rouse her, for she was deaf to all but the call of the wolves.

Thus she took off her shoes, for it was late and dew lay heavy upon the ground, and set off barefoot along the cattle tracks towards the swamp, a distance of almost three versts.

Yet these paths were trodden by the cattle and they twisted and twined hither and thither, and all the time Aalo’s heart throbbed like a bird in her breast.

After walking for a time Aalo finally arrived at the edge of the great swamp, which seemed to be enveloped in a thin white mist, so covered was it with blossoming marsh tea and cloudberries and hare’s-tail. And here the sounds of the village could no longer be heard, nor the crowing of the cock nor the barking of the hounds, nor even the peal of the church bells.

And the swamp appeared to have a hundred eyes, between the tussocks, their dark surfaces staring silently at this young wife as she wandered through the night.

But Aalo skipped from tussock to tussock, as dwarf birches and cranberry tendrils tugged at the hem of her skirt as if to hold her fast.

And so she finally arrived at the small island in the centre of the swamp, where pines and blackthorns and rowans grew, where great anthills stood and where the ground was hard and covered in pine cones and needles.

Then Aalo recalled the ancient charm, snapped a branch from the blackthorn bush and waved it thrice across the quagmire.

And lo, she looked on as the bracken at the swamp’s edge burst into a blue flower which shone like a blue flame.

For the villagers say that bracken only flowers once a year, on Midsummer’s Eve.

And thus around this blue bracken flower, which flickered like blue fire, as if the heart of the swamp had lit up, danced the grass snakes, some with their heads held up high, some twisting in circles on the ground, and there were many hundred of their kind. And all the gnomes and will-o’-the-wisps of the forest bowed down on either side of the flower as if it were a sacrificial flame.

And upon the island in the swamp was a large group of wolves, even though it was summer-tide, as if all the wolds of Kõpu and the shadows of Kõrgessaare had released their wards, and all the wolves of Muhu and Saarenmaa and from as far afield as the mainland had joined their pack. They were sitting in a large circle, as if at a meeting of elders, their bushy tails at their heels and their thick coats tangled, but no longer did they howl.

At once Aalo perceived a large wolf sitting towards the front of the group, and realised that this was the very same wolf which at the hunt at Suuremõisa had escaped through the line of men; she knew it from its great, powerful frame and from the wild gleam in its eyes, and she understood that this was the leader of their pack.

Then she noticed, hidden within a large rock, a pristine wolf skin a deep colour of grey and yellow.

And thus at that moment the Devil snuffed out all that was left of Aalo’s former life, as quickly as if the swamp had sucked her deep into its embrace for the rest of time, and no longer could she recall her husband, her child, the servants, the cattle, neither the Word of the Lord nor His Mercy.

(For such powers has the Devil bestowed upon his dæmons that they may conjure up hail, frost and wind and can poison the air and the water, and even turn people into wolves.)

And with that Aalo threw the wolf skin across her shoulders and soon she felt her bodily form becoming all but unrecognisable; for her white skin was covered in a tangled coat; her dainty little face narrowed into the long muzzle of a wolf; her small, pretty ears grew into the pointed ears of a wolf; her teeth turned to ferocious fangs and her nails to the curved claws of a beast of the wilds.

But so skilfully does the Devil in his infinite cunning fit a wolf skin around the frame of a human that the claws and the teeth and even the ears each fall at exactly the right place, as if she had been taken from her mother’s womb thus and entered this world as Lycanthropus – a werewolf.

And in the form of the wolf, so Aalo also began to develop the cravings and desires of wolves, such as a thirst for blood and a rejoicing in slaughter, for her blood too had become the blood of wolves, and with this she became one of their number.

Thus with a wild and raucous howl she joined the pack of wolves, like a prodigal daughter she understood that finally she had found her like, and to a chorus of howls the others greeted her as their lost sister.

Chapter Six

And so it was that upon this light Midsummer’s night Aalo, wedded wife of Priidik the woodsman, ran for the first time as a werewolf.

For barely had she been transformed into a wolf and joined their number than the wolves left the island in the swamp and the whole pack galloped through the wilds, crossing heath and bog as they headed north-east towards Kõpu and Kõrgessaare, Aalo amongst them.

And Aalo sensed that both she and the world around her had changed through and through, everything felt new and fresh, as if her mortal eyes were glancing upon these things for the very first time, in the same way as our foremother Eve, when at the snake’s bidding she plucked and ate the apple from the Tree of Knowledge in Paradise.

For now the muscles in her loins and the sinews in her sides were tensed with a new, mighty power, and now no distance was too long for her; she leapt lightly across the quagmires and over felled trees and in her gallop there was a pace as terrific as the Western Winds.

Both swamp and forest were brimming with scents which, in her human form, not once had she noticed, and these scents excited her greatly, for she was compelled to run after each and every one of them. For in some strange way, which defies all explanation, she knew precisely which scent belonged to which animal dwelling in the forest. And so her nostrils were filled with the now familiar scents of far off creatures: squirrel and fox, snipe, grouse and capercaillie, even hare and hedgehog.

But as on their nocturnal flight they neared a solitary hut in the woods or skirted far around the village, thus a wave of new and wonderful smells flooded towards them, making Aalo’s blood flow all the quicker, for now, amidst the smell of cattle, she sensed the smell of ewes and kids and young foals, and this made her swoon and her blood boil, for now she too was one of the wolves.

Still one more scent came their way, wafting out forebodingly from between the forest huts, and so strange and pungent and frightening was this smell that she felt her new wolf’s heart shudder in her breast. At this she saw the other wolves, her sisters and brothers, stop still for a moment, sniff the air, then redouble their speed as they galloped onwards, as if this scent brought with it certain death and destruction and was a sign of the sworn enemy.

For as between the snake, that worm of old, and humans, so the Creator also established an eternal hatred between wolves and mankind, and in this way they are destined to despise each other always.

And at that moment from a far corner of the village Aalo’s sharp lupine ears heard a short crack, followed shortly by a flare and a loud boom like thunder, and with that, blind with fear, they dashed headlong into the darkest shadow of the forest.

Yet even in her new form Aalo too was suddenly filled with true caution; everything was suspicious, as if danger lurked all around her. Thus she carefully sniffed every twig and branch upon the path, as if a wolf pit may be hidden beneath them or a trap may lie set behind the bushes.

Never in her former life had her blood bubbled with such golden glee and freedom’s fancy as now, galloping across the swamp as a werewolf. For such a fury of freedom is unpredictable and forged by the Devil himself, so that he may lure his young victims into the chasm of destruction.

And when she looked more closely at her companions the wolves, as together they ran that Midsummer’s Night the length and breadth of Hiidensaari, to her great surprise she saw amongst them a number of people well-known from her human life.

For running abreast her was another werewolf, the Valber woman from the village of Tempa, and beyond her was the churchwarden and a wealthy landowner from the manor at Suuremõisa; and she knew she was not mistaken, for with her wolf’s eyes she could see more clearly than ever she had with her human eyes. As she ran by, Valber bared Aalo her sharp, curved fangs as if to greet her old acquaintance.

Then suddenly they heard the bellowing of the cattle and noticed a heifer that had strayed from the flock at the edge of the meadow.

And upon that very moment Aalo knew that her lupine nature thirsted and craved for that heifer’s blood.

She saw the large wolf, the leader of the pack and much more powerful that the others, as it ran ahead and set upon the heifer, tearing at the veins in its neck.

Thus Aalo was engulfed by a great fever, and she could no longer understand anything clearly as she cast off the final remnants of her former human nature. And at that she joined her sisters and brothers in attacking the heifer, and together they tore it to pieces.

They slaughtered many cows that night, and ewes and young foals too.

And this baptism of blood is the Baptism of Satan as thus he strengthens his union with that which is human.

But as they galloped further and further towards the north-east and the great wolds of Kõpu appeared on the left and Kõrgessaare in front and the open sea began to loom ahead through the white night, the wolves, which had until now remained close together, dispersed and began running alone or in twos.

And at this Aalo found herself running alongside the greatest of the wolves, which she had seen evading the hunt at Suuremõisa.

With that she realised that this was the wolf which had thrice called her to the swamp that evening and which had finally come for her.

And to her surprise Aalo felt that she was the equal of this great, potent beast, and that she could follow his every step though he quickened his pace, and they seemed to be flying across the heaths and the marshlands.

For it was that same ferocious fire burning the blood flowing through their lupine veins and that same glorious glow making their lupine hearts race.

And together these two were the noblest and most splendid of all the forest and of all St. George’s beasts.

Thus in the early hours, just before dawn, their journey took them to the wolds of Kõpu, to the heart of the ancient spruce forests, where man’s axe had never struck and where age-old lichen-covered trees hid the mossy forest floor beneath their dark shadows.

The wind rustled through the treetops, sighed a great sigh, then died down once again.

At that moment the wolf with whom Aalo had been galloping suddenly changed his form.

Through the forest there gusted a mighty wind, living and breathing, as if an enormous lung had sighed, and all the wilds shuddered to the thud of unseen footsteps and a pair of great wings, whose span no mortal has ever measured, which more than the tops of the ancient trees shrouded the forest in a clandestine darkness.

For this wolf was Diabolus sylvarum, the Spirit of the Forest, though he only chose to reveal his true form now.

And upon this such a bliss came over Aalo as has no bounds and her soul was filled with an overwhelming joy, such as cannot be described in human tongues, for nothing can compare to the wonder and wealth of her elation, a fountain for those who thirst. For at that moment she was one with the Spirit of the Forest, that potent dæmon who in the shape of a wolf had chosen and claimed her for his own, and thus all boundaries fell between them and they became one, like two drops of dew which, once thus conjoined, cannot be put asunder.

And Aalo evaporated into the hum of the forest spruces, she oozed as a golden resin from the red trunks of the pines, she disappeared with the green dew upon the moss, for now she belonged to Diabolus sylvarum and had fallen prey to the Devil.

But when Aalo next awoke, she realised that she was resting upon the side of a large rock close to their cottage in Pühalepa, and beside her lay the wolf skin. As the sun rose from its short repost that summer’s night, Aalo quickly hid the skin in a hollow in the rocks and hurried home to her bed before anyone could notice that she had ever been gone.

Chapter Seven

And from this night forth Aalo was the daughter of damnation and in league with the Devil, and like the witches of Blocksberg she began to run as a werewolf, for now it was as though she had two lives: one as a wolf and one as a human.

(If any man of a doubtful disposition should question whether these events are possible, may he read for his enlightenment what the philosophus Pomponatius has written and published, or the works of Theophrastus Bombastus Paracelsus and Thomas Aquinas, or indeed what the Council of Ancyra Anno 381 proclaims in a treatise, which begins with the words: Quisquis ergo aliquid credit posse fieri …)1

Thus during the hours of daylight she remained in her former human body, and no one noticed anything amiss in her appearance, though she was perhaps paler than before and there was less expression in her eyes, as if she were staring into secret, forbidden depths. And when in the evenings she took off her headdress her hair seemed ablaze with an even ruddier glow than before, like fire raging upon pine logs.

But in no way did she neglect a single one of her chores, but took care of everything like the dutiful housewife she once was, from the first chores of the morning to the last of the evening. And so she milked the cows, ground the handmill, suckled her child upon her breast and hoed and ploughed the fields as did all the other women of Hiidensaari. Indeed, it appeared that she was twice as diligent in everything she did, her hands and feet twice as nimble and her words to her husband Priidik all the sweeter. And many a man who saw her skipping back and forth across the garden to the well, like a bobbin between the threads of the loom, thought in his heart what a lucky fellow was he who could call this fond and fair woman his wife.

But when night came and Priidik had drifted into the heavy, weary sleep of a woodsman, so began his wife Aalo’s other life, which during the day was carefully hidden, just as bats and moths awake from their slumber at night and nocturnal flowers begin to blossom for the night alone.

And this was the life she led at night, for it was of the night, of darkness and of the Devil.

For no sooner had Aalo noticed her husband Priidik drifting into sleep than she could feel her wolf’s instincts bubbling in her blood, as if her other nature, by day suppressed deep within her, at night awoke and overwhelmed her with its potency.

For she, who once had been meek and mild, was now bold and blood-thirsty; she, who once had been timid, was now untamed; she, who once had been chaste, was now brimming with lust.

And now every night Aalo, wedded wife of Priidik, surrendered herself wholly to her new lupine nature, and as her husband slept soundly she leapt from their marital bed and ran through the forests as a werewolf.

Then, as upon Midsummer’s Eve, she willingly took part in the wolves’ nocturnal journeys, and there was no bloody deed as would have appalled her nature, no Devil’s dance in which she would not have whirled like a flake of snow blown by a gust of dæmon’s breath.

At night the Spirit of the Wolf and of the Forest was wild within her and she was ready to do whatsoever Diabolus sylvarum commanded her to do, be it robbery or murder, or even blasphemy against the Almighty.

For now she belonged to Diabolus sylvarum in a strange and secret way, with all her body, with all her soul, as strongly as if she had entered a blood union with him.

Yet although Aalo celebrated the witches’ Sabbath and ran through the forests as a wild beast each and every night, at first no one so much as noticed she was gone, for before the crow of the cock each morning she had returned and was lying beside her husband Priidik. Neither did any of the villagers realise that she had any part in the disappearance of kids and lambs, for they blamed the real wolves.

But if the Lord in His forbearance now and then allows Satan and his henchmen to run wild, in time He will nonetheless clench His fist around their tether once again and pull with all His might.

And it so happened that one morning the innkeeper from Haavasuo stopped by the cottage of Priidik the woodsman and as they exchanged words of greeting he said:

‘My finest ewe is lost once again, for last night it was savaged by that forest cur.’

Thus Priidik the woodsman asked:

‘Tell me, dear man, how has such a dreadful deed come to pass?’

And to this the innkeeper replied:

‘Last night, when I heard bleating coming from the paddock, I went outside to look and saw that beast amongst the lambs. So I quickly looked for my musket and aimed it at the fearsome foe, and perchance I struck it in the foot, but alas the beast had already caught a lamb for itself and leapt limping into the forest.’

But barely had these words left his lips than Aalo, wedded wife of Priidik the woodsman, entered the cottage carrying a pail of water limping on her left ankle, which was bloody.

At this the innkeeper from Haavasuo fixed his eyes upon Aalo’s ankle and said:

‘Of course, it could also have been a werewolf, for nothing can dispatch them but a silver bullet or elder heartwood. I fear the spread of werewolves has already reached Hiidenmaa, for Valber from the village at Tempa was found to have run as a werewolf and has been delivered into the hands of the gaoler and the executioner.’

And he spoke further, as he continued to stare at Aalo and her ankle:

‘Only this morning did Valber float in water as light as a goose or a reed, even though both her hands and feet were tied and crossed, and only when the local executioner began using the thumbscrew did she confess to running as a were-wolf and visiting Blocksberg. A black man approached her in the forest, she said, first in the form of a haystack, then clothed in fine attire, as she sat binding brooms, and he offered her some sweet roots to eat; at first this tasted as sweet as nectar upon her tongue, then as foul and as foetid as Satan’s spice, and then, from a vole’s den beneath a rock, the man produced a wolf-belt and gave it to her.’

But upon hearing him speak Valber’s name, Aalo’s eyes froze for a moment, and she turned her back on the others.

To this Priidik the woodsman replied:

‘This is indeed a woeful tale for the ears of good Christian folk, yet still the Count of Suuremõisa keeps aspens growing in his forests to ward off the wizards of Blocksberg. Why, my good innkeeper, have you ever seen a wolf-belt?’

And the innkeeper from Haavasuo replied:

‘I have heard talk of them, though I have never seen one. Sometimes it is made of a wolf-skin, sometimes the skin of the hanged, and it is adorned with twelve dozen star constellations. And it is said to be tied around the waist using a buckle with seven tongues, but if even one of them is opened, the spell will be broken.’

At this Priidik the woodsman cried:

‘Alas, that sin should be the burden of our birth! Why, others say a person need only crawl thrice beneath a tree trunk or run thrice around a rock speaking spells and he will be a werewolf made.’

The innkeeper then replied, shaking his head:

‘When Valber was threatened with death by fire and faggot she cried out: if I must burn at the stake, then verily others shall burn with me. What may these words mean? Surely that Valber is not the only werewolf upon Hiidenmaa and that her sisters still run free!’

Thus Priidik the woodsman asked:

‘How can we tell those who run with the wolves, what are their signs and features, so that we should know to beware of them?’

And to this the innkeeper from Haavasuo replied:

‘Many say that werewolves are more pallid than natural people and that often their eyebrows meet above their noses, upon what folk call the Bridge of Beelzebub. And I have heard also that they have witches’ marks upon their bodies, scratches made by Satan himself as he claws at them, and that they do not feel pain, not even if you stick them with a needle. And if a person is found slain in their bed, a small bite upon their left side, this too is the work of a werewolf and means that they are near at hand.’

And all the while, as the men spoke amongst themselves, Aalo stood perfectly still and silent, just like the water in the well.

But before he left, the innkeeper from Haavasuo stretched forth his arms and solemnly sighed:

‘Help us, Heavenly Father, for in the words of Josaphat we beseech thee: wilt Thou not judge them? There must indeed be something woefully wrong with this world, crooked as the roof of Mustapeksu’s barn, and the end nigh for all, when the children of God run in the woods as the Devil’s whelps.’

And with those words he went on his way.

But when Priidik the woodsman and his wedded wife Aalo were once again alone in the cottage, Priidik too looked at Aalo’s ankle, doubt burning his brains, and said:

‘Why are you limping, wife? You were fine yesterday.’

But Aalo replied meekly, as was her wont:

‘I knocked my ankle upon a sharp stone at the well, and look how it bleeds!’

And with that she tore a piece of linen and bandaged her wounded ankle to stop the bleeding, and they spoke no more of it on that occasion.

For Aalo was still surrounded by a magic force, full of the secrecy of witches and the Devil, and it was such that no mortal could yet break asunder.

Chapter Eight

But one night in the month of August, not long after these events, as the harvest was almost ready and the nights began to darken, Priidik the woodsman awoke in his bed, a draught making him shiver. And as he was fumbling for the wolfskin he realised at once that he was alone and that his wife Aalo’s place beside him lay empty.

At this a strange shudder shook his soul, like a shadow cast across the room darkening it for a moment, he prayed thrice and said:

‘May the Lord and His Holy Angels look over her so no harm shall come to her, neither to her body nor to her soul, for she is as fragile as the finest glass, though her body is young and strong.’

But sleep no longer touched his eyes, and all night he remained wide awake, waiting for his wedded wife Aalo to return.

Thus finally the cock crowed in the farm, then another on the neighbour’s grounds, and finally a third further off as a signal that night was gone and morning arrived.

And at that very moment Aalo his wife stepped through the door into the cottage and made straight for her bed.

Upon this Priidik the woodsman, pretending to be asleep, opened his eyes and said:

‘Where have you been, wife? Whence do you come?’

And Aalo replied:

‘I was in the birch grove tying up bath whisks, for tomorrow is Saturday and we shall bathe.’

And in her clothes and in her hair hung the scent of the forest and of marsh tea, of moist boggy moss and of marsh mud; heavy and dizzying, like bog and bilberry.

At once Priidik sensed this strange, fragrant scent as it filled his nostrils, as though the forest and all its inhabitants had been brought inside and filled the cottage, and he said:

‘Day is for daytime chores, and night is for sleep and rest. Never before have you wandered to the woods at night.’

But when Aalo threw herself upon the bed, so the scent of the forest and of the swamp in her hair grew stronger, as if a wild forest beast had lain in the bed beside him, and not a young woman at all.

And he felt a secret surrounding her, one he could not explain, and his soul sensed in this secret a formidable foe, just as wild creatures sense a brewing storm.

With that he pushed his wife Aalo from him, so repulsed was he by this scent that he could not accept, for like a foreign Element it was against his nature.

At this he said:

‘How comes the scent of the swamp in your hair?’

And Aalo replied:

‘I went awandering by the swamp and gathered marsh tea in my apron to boil medicinal water. I may have had a branch in my hair for a moment.’

But Priidik the woodsman felt his heart tremble with pain that his wife should so brazenly lie to his face that he sat up in bed and said:

‘You are lying, woman! You smell of wolf and not of the woods! Where have you been?’

And when Aalo did not say a word in reply lightning flashed through his soul and he shouted:

‘Surely you did not spend the night running as a werewolf?’

But as soon as he had uttered these words Aalo began to quiver, so determined was her husband in pursuit of the truth.

And with that Priidik realised that he had indeed uncovered the truth, as easily as had he ensnared it in a trap, and shouted:

‘O, my woeful wife, have you fallen into the hands of He who ravages the spirit? Was it you who took the innkeeper’s sheep? Are you in league with the werewolves and the witches of Blocksberg?’

To this Aalo replied:

‘What nonsense you speak, else it is the ale inside you talking.’

And Priidik said:

‘My wife, there was a time you did not know how to lie, and your speech was nothing but the yea and the nay of the righteous!’

And at this he demanded:

‘Do you run with the wolves or not?’

Thus Aalo finally replied:

‘And if I do run with the wolves, if it is wolf’s blood which burns in my veins, then there is nothing any of you can do, for the bliss and the damnation in my soul are mine alone.’

At this Priidik shouted:

‘Thus you confess, you are indeed a werewolf, cut off from the company of Holy people, and Christ nailed in vain to the cross for your soul!’

And unto this Aalo said:

‘Listen to me, Priidik, for my breast burns like coals in the fire! Though I spend the hours of day with other people, and though I have a human form, so my spirit yearns for the company of wolves whenever night is near, for only in the wilds have I such freedom and joy. And thus I must go, for I am the kin of wolves, though indeed I may be burnt at the stake as a witch, for this is how I have been made!’

But Priidik replied:

‘Do not blaspheme the name of your Creator, woman, for you have been shaped by Satan himself.’

Yet search though he may as he looked upon his wife Aalo, he could see in the eyes of the Devil’s child neither insolence nor brazen impenitence, for the woman beside him was timid like a forest creature and a beautiful sight for her husband’s eye to behold.

But at that same moment he recalled that the beauty of the face is also Beelzebub’s bait, as the wise Syrach forewarned: ‘Turn away, my sons, turn your eyes from beautiful women, for many a man has their beauty maddened.’

And thus he further cursed his wife Aalo and said:

‘Is this the meaning of the mark beneath your breast shaped like a night butterfly? Fie, what a fool I have been, that I did not notice this before and take heed. For truly it is a witch’s mark and the fingerprint of the Evil One himself!’

To this Aalo replied:

‘It is not a witch’s mark; my mother took fright as the barn was ablaze, and thus my breast was marked inside her belly.’

At this Priidik scoffed:

‘The Devil has indeed marked you at birth with his branding iron, so that he will know his own.’

And further he asked:

‘When you are in the forest, do you visit the Devil?’

And Aalo replied:

‘The Spirit of the Forest comes to me.’

And Priidik asked:

‘In what form does he come to you, as a man or as a wolf?’

And Aalo replied:

‘Neither as a man nor as a wolf, for he has neither form nor body: he is everywhere, invisible, like a spirit.’

Thus in his bitterness Priidik said:

‘Who are you, my wife? Do you truly have two natures, one meek, one wild as the forest beasts, each taking their turn to overpower you, one thirsting for blood like the wolves, whilst the other has all the virtues of a wife!’

And at this his soul was consumed with darkness as he thought of how those beautiful limbs had been abused by Satan for his shameless deeds.

And thus he asked:

‘Do you drink blood with the same lips as kiss your husband and take the Holy Communion?’

And Aalo replied:

‘When I am a wolf, I do the deeds of wolves.’

At this Priidik the woodsman exclaimed in a booming voice:

‘That my eyes should see the wife I first beheld as a young maid amongst the lambs now attack those same lambs as a werewolf and drink their innocent blood!’

And with that he quickly stood up, reached for his musket hanging on the wall, and threatening his wedded wife Aalo he shouted:

‘Out of my sight, wolf’s whore! Go and join your kin!’

And thus Aalo’s hands dropped from the side of the bed, to which in fright she had clung, as a drowning man clings to a log as the waters swallow him into their depths, just as her soul now left her body, leaving forever the community of Christ and the protection of the church.

Thus Aalo hurried past her husband, through the door and into the garden, and from there into the forest she ran, along the pathless paths of the wolves to join her sisters and brothers in joys which belong not to humans, but to wolves, and are eternally shrouded in secrecy.

1‘He, who believes that something may happen …’