4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

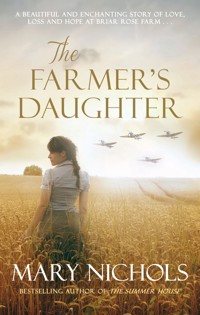

June, 1944. Since her father's stroke, Jean has been trying to run her parents' small farm almost single-handedly and is in desperate need of help. Karl, a German prisoner of war captured when the Allies invade France in 1944, turns out to be just what she needs. He is polite, hardworking and homesick, but is he more than that? Fraternisation between the prisoners and the local population is forbidden, but as the weeks and months pass, Jean and Karl become closer - much to the dismay of Jean's family and Karl's compatriots. Can their love have a future when it seems every hand is against them?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 512

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

The Farmer’s Daughter

MARY NICHOLS

Contents

Chapter One

6th June, 1944

‘This is the BBC Home Service and here is a special bulletin read by John Snagge.’ The familiar voice of the newsreader filled the farmhouse kitchen. ‘D-Day has come. The first official news came just after half past nine when Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force issued Communiqué Number One. This said: “Under the command of General Eisenhower, Allied naval forces, supported by strong air forces began landing on the coast of France …”’

‘It’s happened at last,’ Jean said. It was something the whole country had been speculating on for months. The war had been going in the Allies’ favour ever since Rommel had been ousted from Africa at the end of 1942. At that time, Prime Minister Churchill told the nation: ‘This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.’ Was this, then, the beginning of the end? The signs had all been there: you couldn’t hide thousands of troops on the move by rail and lorry, holding up the trains and clogging the roads, and the huge increase of bombers flying overhead; the British at night and the Americans during the day. And no one was allowed to go within ten miles of the coast, all the way round from The Wash to Land’s End.

Her mother stopped fussing round her father’s wheelchair and sat down to listen while the newsreader went on to give more details: the huge numbers of ships, aircraft and troops and how the attack started at midnight with airborne troops landing behind the lines. There had been some tough fighting, but losses were lighter than expected and everything was going to plan. The king would make a broadcast at nine o’clock.

‘Do you think that means the war’s nearly over?’ Doris queried. ‘Will our boys be coming home soon?’ Her first thought, as always, was for her son. Gordon had been captured when his Spitfire had been shot down over northern France, while trying to defend the troops on the beaches of Dunkirk, and he had been a prisoner of war ever since.

‘Let’s hope so.’ Jean said, as the newsreader continued with other items: the American Fifth Army had entered Rome unopposed to find the German army gone. Daylight brought thousands of Romans out onto the streets, to greet their liberators with flowers, hugs and kisses. The Russians were advancing in the east, while at sea, the Allied shipping losses were down to 27,000 tonnes, the lowest figure of the war. All seemed set for victory. ‘I’ll catch it later,’ she said, leaving her parents to go back to work.

She had been up since dawn, milking and looking after the livestock, a task which had devolved on her shoulders since her father’s stroke. Their farm was a mixed one of pasture for a small dairy herd and a few sheep, with some acres of arable land on the slightly higher ground. Higher ground in the fens meant a bump of land that might, in pre-drainage days when the area was under water much of the time, have been a small island. Pa and Gordon had managed very well with casual labour at busy times, but the war had changed everything. Gordon had not waited to be called up and joined the Royal Air Force as soon as war was declared, much to their father’s annoyance. ‘How am I to run the farm without you?’ he had demanded on being told the news.

‘You can get help.’

This had proved impossible; most of the village men had either followed Gordon’s example and joined up or they had their own farms or employment on other farms. Jean had given up her job in Wisbech to help out and they had managed with casual labour, but she was nothing like as skilled or as strong as her brother, a lack which her father was not slow to point out. One evening three months before, after a particularly stressful day, Pa had fallen down in a heap, his face distorted and his left arm useless. He had been taken to hospital where they did the best they could for him, but his left arm was useless, he could no longer walk and his speech was slurred. He was only fifty-two – no age at all. It had been left to Jean to take over the running of the farm and dealing with the mounting paperwork, although her father still thought of himself as the boss and he would make the decisions about what needed doing and when. Usually Jean obeyed, but on occasion made up her own mind what to do.

Leaving her mother to the housework, she went out to see to Dobbin and Robin, the two cart horses. Some of the farms had the new tractors imported from America, but on Briar Rose Farm they were still using horses. A tractor was on order, but they had to wait their turn to have one and Pa was in no hurry; he had heard they were nothing but trouble, were devils to start and were always breaking down. Horses were more reliable, even if they were slower.

She let them out to the pasture to graze, then went up the lane to the potato field to hoe between the rows. It was hot, dusty, back-breaking work and she stopped only for a sandwich and a flask of tea in the middle of the day. At five o’clock she left off to fetch the cows into the cowshed to milk them. It was seven when she went back to the house.

Her mother was laying the table for supper in the large flagstoned kitchen. There was a big table in its centre, a coal-fired kitchen range and a dresser along one wall displaying crockery. A rocking chair stood in a corner and a cat snoozed on the hearthrug. ‘Give the boys a shout, will you, Jean?’ she said.

Jean went to the back door to call her fifteen-year-old brother, Donald, and Terry Jackson, their evacuee, who was a couple of years younger. She had to shout twice before they appeared from the direction of the barn.

‘We caught more rats,’ Don said. ‘Six yesterday and four more today. We put the tails in a bucket.’ The tails were docked so that children could not claim their penny-a-tail more than once.

‘All right, that’s ten pence we owe you,’ Doris said. ‘Don’t you dare sit down, either of you, until you’ve scrubbed your hands.’

They went to the sink to obey, while Doris wheeled Arthur’s chair up to the table and they sat down to eat. There were plenty of vegetables with water or home-made cider to drink and for a while there was silence.

‘How was school today?’ Doris asked Donald. He attended Wisbech Grammar School, while Terry went to the village school which took pupils from five until they left at fourteen.

‘OK, I suppose. We had special prayers in assembly on account of D-Day. They changed our lessons so they could tell us about it. But I knew something was up before that. I heard the bombers going over last night. They woke me up. I tried to count them, but there were too many. Thousands and thousands. They blotted out the sky.’

‘We’ve got Jerry on the run now,’ Terry added, with the grin that almost always resulted in him being forgiven for any misdemeanour he had been engaged in. He had arrived in the household in September 1939, a bedraggled, bewildered eight-year-old, who had taken weeks to settle. His behaviour had been erratic and unpredictable and for a time they wondered what they had let themselves in for, but Jean, who had a great capacity for love, had gradually won him over. He had shown his mettle when Arthur had his stroke. Somehow the incapacitated man struck a chord with him and they had become great pals.

‘Have you done your homework?’

‘I’ll do it later.’

‘You will go and do it as soon as we’ve finished dinner. What about you, Don?’

‘It’s history. I hate history.’

‘Nevertheless, you will do it.’

Once the meal was finished, the boys went reluctantly to their homework and Jean helped her mother clear away and wash up. ‘We need more help,’ she said, voicing what had been in her mind for some time. ‘I can’t cope on my own. There’s hay to cut and the wheat will be ready for harvesting soon. The ditch on the bottom field needs clearing and the hedges are getting untidy. And I’ve only managed to hoe half the potatoes today.’

‘Not in front of Pa,’ Doris murmured, nodding towards her husband dozing in his wheelchair. ‘You’ll only agitate him.’

Jean subsided, but the problem was still on her mind as she left the kitchen to go into the sitting room to deal with the farm accounts and fill in yet more forms. The trouble was that it was almost impossible to get help. All the farms in the neighbourhood were short-staffed. With the men away in the forces, their numbers had been made up with Italian prisoners of war and girls from the Land Army, many of whom were town girls and had no idea about farming. They were learning, it was true, and their help was better than none, but they had to be shown what to do and how to do it and it all took time. ‘Fat lot o’ good they are,’ her father had said when she had first mooted the subject. ‘We’ll manage without ’em.’ But he could not have known he would be incapacitated by a stroke, and even now expected to recover fully and go back to work. She did not think that was likely in the immediate future and something had to be done.

For the next few days everyone was glued to their wireless sets, listening to bulletins as more and more details of the invasion emerged. There was fierce fighting and the first day objectives had not all been taken. The American advance was slower than had been predicted; the terrain was swampy and there were more German troops facing them than had been expected. Caen, an important town for communication and supplies, was still holding out in July. It soon became clear that Hitler was not going to give up and so the slaughter and the taking of prisoners went on.

Going to church was a Sunday ritual for the Coleman family, as it was for most of the older villagers. Here they met to worship, but also to gossip and grumble and share experiences. At the beginning of the war when everyone expected an invasion, the bells had been silenced, only to be rung as a warning that the Germans had landed. The ban had been lifted now and the bells could clearly be heard ringing out over the village.

Terry pushed Arthur in his wheelchair, while the others walked beside them. As they approached the church, the eight bells stopped their carillon and were followed by a single toll which told everyone to hurry. The wheelchair was hoisted over the church step; Don and Terry, who were in the choir, went to the vestry to put on their cassocks, while Jean wheeled her father up to the pew at the front where there was room to park it. Sir Edward and Lady Masterson always occupied the front pew on the other side of the aisle but they had not yet arrived and the service would not begin until they did. Sir Edward owned most of the land in the village including Briar Rose Farm, but he was a benign landlord and, so long as they paid their rent on time, rarely made his presence felt. Their son, Rupert, a captain in the Cambridgeshire Regiment, had been captured when Singapore fell and they did not know if he were alive or dead and, in that respect, he shared the troubles of some of his tenants.

Miss Dawson, the elderly schoolteacher, played the organ while the congregation trooped in and took their places. Besides the villagers, there were some Americans from the nearby base and one or two British airmen who were convalescing at Bushey Hall after being wounded. When the squire and Lady Masterson arrived, the Reverend Archibald Brotherton, with the choir behind him, followed them up the aisle. He conducted the service in the traditional way and everyone could follow it automatically, leaving time to let their thoughts wander. Jean prayed along with everyone else, that the war would soon end, that prisoners would come home, the missing turn up safe and well, and those who had suffered tragic loss would learn to live again. ‘And let Pa get better,’ she added.

She turned to look at him. He was staring up at the pulpit, where the rector had gone to deliver his sermon. Sometimes he answered back if the parson said something he disagreed with, which embarrassed his wife and drew a smile from the reverend. Today the sermon was about patience and tolerance and loving one’s enemies, which didn’t go down too well with those who had suffered. She watched her father carefully, ready to lay a restraining hand on his arm.

‘The Boy Scouts will bring their collection of paper and metal to the village hall on Saturday afternoon, where a lorry will be waiting to take it away,’ the reverend added, after ending the sermon. ‘The Women’s Institute has arranged a talk about preserving fruit and vegetables which will be held in the church hall on Friday beginning at 7.30 p.m. All are welcome.’ He paused to look round as if assessing who was present and who was absent. ‘We will conclude with hymn number 217: “Thy Kingdom Come, O God, Thy rule, O Christ, begin; Break with Thine iron rod, the tyrannies of sin.”’

With the ending of the hymn, he blessed the congregation, crossed himself and left the pulpit, to be followed down the aisle by the choir, Sir Edward and Lady Masterson and the rest of the congregation. Everyone gathered in the churchyard to comment on the latest news. It was not just the battles abroad, overhead and at sea that filled their minds, but the effects of war at home.

Everyone had been forced to tighten their belts. Everything was either rationed or in short supply. Things like cigarettes, razor blades, safety pins, hair clips and lipstick disappeared under the counter. The ‘utility’ label was on almost everything manufactured: clothing, furniture, bedding, pots and pans and carpets, which meant they had to be made to strict guidelines. Even those were hard to come by. To save paper, newspapers were confined to four pages and very few books were being published, although there were leaflets in abundance with notice of new regulations, endless recipes for using the bounty of the countryside, and instructions for remaking old clothes into new.

‘Have you seen what they’ve done up at the camp?’ Mrs Harris asked Doris.

‘No,’ Doris said. ‘I haven’t been that way for some time.’

‘Well, I don’t usually, but Ted Gould has been working up there and he told me that they have extended it to take thousands more prisoners. We’ll be inundated. I don’t like it.’

Most German prisoners taken earlier in the conflict had been sent on to Canada and America where it was thought they couldn’t cause trouble, but a few, mostly submariners and Luftwaffe, had remained on British soil. Bushey camp housed a few hundred of them but they were confined behind a high wire fence and had caused no trouble.

‘I suppose they’ve got to put them somewhere,’ Jean said.

‘Not on our doorstep, for goodness’ sake.’ This from Mr Harris.

‘I can’t see how you are going to stop it,’ Bill Howson said. ‘The government can do what it likes.’

Bill owned his own farm on the other side of the village, where he lived with his widowed mother. Jean had known him since he was a grubby five-year-old with wrinkled socks who persisted in treating her as one of the boys. He had grown out of that and was now a strapping six-foot hunk of a man, good-looking in a rugged kind of way and strong as an ox. The land girls who worked on Bridge Farm all sighed after him. Jean had been going out with him ever since they left school and most people assumed they would eventually marry.

‘I’ve finished cutting my wheat,’ he told her, as they took their leave of Mr and Mrs Harris and he fell into step beside her. ‘I’ll lend a hand with yours like I usually do.’

‘We’re waiting for the reaper,’ Jean said. Because the Colemans only had a very small acreage they did not own a reaper-binder but hired one by the day. Jean had put in a request for it and was waiting to be told when it would be her turn to use it. There was only one field to cut; given good weather, it could be done in a day.

‘Let me know when it’s coming and I’ll alert everyone.’ He meant the villagers who traditionally helped each other at harvest time.

‘Thank you.’

He let the others go on ahead and took her hand. ‘You are looking tired, Jean. Looking after that farm is too much for you.’

‘I manage.’

‘If you need any help with jobs, just let me know.’

‘Thanks, but you’ve got enough to do on your own farm,’ she said. ‘And it’s not just a few jobs, it’s everything. I’ve advertised for a farm worker but so far I’ve had no reply.’

‘Well, you wouldn’t, would you? Try the Land Army.’

‘Would they be better than the Italians?’ The Italian POWs had been reclassed as collaborators since Italy had changed sides. They were allowed a certain amount of freedom and made full use of it.

‘Lord, yes. The men are far more interested in singing and flirting than work and they will down tools at the first excuse. Either it’s too hot or too cold or too wet. I wouldn’t like to think of one of them annoying you.’

‘Do you think I can’t look after myself?’

‘You’re a woman and a very pretty one at that.’

She laughed at the unexpected compliment. ‘A woman doing a man’s job. There are lots of us doing that, you know.’

‘I know. I wish you didn’t have to.’

‘I don’t mind. I just want to find some help from somewhere. We managed while Pa was well, but now it’s all getting on top of me.’

‘You would have to apply to the War Ag.’ He said, using the popular name for the War Agricultural Executive Committee, an arm of the Ministry of Agriculture. ‘They do the allocation of labour.’

‘Thanks, I will. In the meantime the boys can help when the school holidays begin.’

‘OK, the offer’s there if you want it. I must go or Ma will be worrying where I’ve got to. Fancy the pictures on Saturday?’

On Saturday evenings, Jean usually allowed herself a little leisure. Sometimes they went to the cinema in Wisbech, sometimes to a dance or to listen to a talk in the village hall which might be about any subject the organisers thought might interest the population: natural history, what other people were doing for the war effort, cookery, jam-making, make do and mend.

‘Yes, I’d like that.’

‘OK, I’ll call for you at six-thirty.’ He veered off towards the middle of the village and Jean hurried to catch up with her parents.

As they approached the farmhouse from the lane, she was filled with a feeling of pride and love for the place which had been her home all the twenty years of her life. It was a large rambling structure of brick and flint, typical of the area, with small windows and a pantile roof. On one side, across the concrete yard were the farm buildings; stable, cowshed, and barn. The house and outbuildings were unusually extensive, considering the small acreage they farmed. According to her father, there had once been at least twice as much but, in the bad farming years at the end of the last century, her grandfather could not afford to pay the wages of his labourers and had reduced his holding, leaving only as much as the family could manage.

The war, with its emphasis on feeding the population, had made a big difference. There were subsidies and fixed prices to help them and they were now fairly well off. They had to work hard for their money, but everyone had been brought up to that and accepted it as a matter of course. What would happen when hostilities ended she had no idea.

Once home, Donald and Terry went off to change out of their Sunday clothes to go out and let off steam with Laddie, the collie, at their heels. Doris wheeled Arthur into the kitchen to sit by the hearth while she finished cooking Sunday dinner. They had recently slaughtered a pig and the smell of roast pork permeated the kitchen. Since everyone was being encouraged to keep a pig, there were pig clubs springing up in the most unexpected places, even on urban allotments. Slaughtering, which had to have official approval, was done in rotation so that the meat could be distributed among all the members in turn. What was not to be eaten immediately was salted down or smoked to preserve it. Swill buckets were placed everywhere for people to put their scraps in. There was one outside their gate, one outside the village hall and even one in the school playground. It all went towards keeping the pigs and population fed. Those who kept pigs on a larger scale had to keep meticulous records and send all their animals to the pig marketing board. It didn’t alter the fact that they sometimes cheated.

‘Bill says I have to apply to the War Ag. for help,’ Jean told her mother. ‘They will send whoever is available.’

‘Then you had better do it. I’ll square it with your father. He’ll have to face facts, he isn’t going to go back to work yet awhile.’

Karl had never seen so many ships, thousands and thousands of them, all steaming towards him, bent on destroying him, or so it seemed. The biggest of them were pounding the shore with their heavy guns. The noise was ear-shattering and the heat was so intense it was sending rivulets of sweat running down his back and trickling down his forehead into his eyes. He crouched in the shallow depression in the ground, while shells burst all round him, making more craters and sending up clouds of earth which caught in his lungs and stuck in the two-day stubble on his chin. They had been expecting the invasion for weeks, but all the signs indicated it would be at the Pas-de-Calais, the nearest French coast to Britain. Even now, faced with an army streaming ashore, his superiors were convinced it was a feint to cover the real landing area. If that were really the case, he dreaded to think what that would be like.

He risked a peep over the edge of the depression in which he was sheltering. All round him were wrecked vehicles, guns, bodies and bits of bodies, blood and flies, black swarms of the little devils. Enemy bombers droned overhead, dropping high explosives and causing more craters. One of them hit a tank and it exploded in a wall of flame. He felt exposed and vulnerable.

Beside him in other hollows, his comrades crouched, waiting for the enemy to advance on them through the smoke. Their orders, coming from Hitler himself, were not to give up a metre of ground. How they could hold it without the help of their own tanks he had no idea. Where were they? Everything was in chaos; nobody seemed to be in command and his own captain had been killed. He wriggled over to Otto Herzig who was crouching in a ditch a few yards away. ‘What do you reckon we ought to do?’

‘I don’t know, do I? You’re the sergeant.’

‘We’d better pull back and try to find our own people.’

‘OK. Lead the way.’

There were only about a dozen of them left. He took them through a wood but stopped when it came out onto a road full of troops being dive-bombed. They scattered back into the trees and dived face down in the damp earth. Above the noise of the tanks and the gunfire, he could hear someone shouting.

He woke with a start and sat up still in the midst of his nightmare and, for a moment, didn’t know where he was. He looked round him. This was not France, not a road under fire, it was a Nissen hut lined with two-tiered bunks and there was an English sergeant standing in the doorway shouting ‘Raus! Raus!’

Wide awake now and all too aware of his situation, he shook himself and swung his legs over the bed onto the cold concrete floor. Everyone else in the hut was doing the same and shuffling off to the ablutions. The war was over for him and his comrades and he would be a fool not to feel relief. He could not admit it, of course, especially in front of those fanatical Nazis who viewed the invasion as nothing but a minor setback. The enemy would be driven back into the sea, they said, and there would be no rescuing them as had happened at Dunkirk. To them, Hitler was invincible.

The British sent all prisoners to holding camps when they first arrived where they were deloused, fed and interrogated. The Tommies were pretty good at that and when faced with exhausted, hungry, dispirited men, soon found out much of what they wanted to know. He hadn’t witnessed any beatings and, as far as he was aware, they stuck to the rules of the Geneva Convention, though rumours were flying that if you were sent to the London Cage, you were in for some rough treatment.

Each prisoner was categorised according to his perceived belief in Hitler’s dogma. Those labelled ‘black’ were the strongest Nazis and likely to cause trouble, the ‘whites’ were opposed to National Socialism and could, in some measure, be trusted. The majority were ‘greys’, neither one nor the other; they had fought for their homeland and for their families, not for Hitler and his cohorts. The blacks were sent to special secure camps. Karl had been considered grey, which meant he had been sent to a normal prisoner-of-war camp, here in the fens of East Anglia.

Life in the camp was boring. The men were left to amuse themselves and, under the direction of the Lagerführer, Major Schultz, and various other volunteers, organised games and entertainments and educational classes to relieve it and keep them occupied. There was even a newspaper put together by the prisoners themselves. It had a page of events and entertainments being staged, the results of sports and games, snippets of gossip and a letters page. News was culled from hidden wireless sets which were tuned in to Deutschlandfunk, and the BBC, translated for those who did not speak English. Being able to read both versions, he was amused by the different slant they put on events.

The attempted assassination of Hitler was a case in point. He had read both accounts, one of which said it proved how unpopular Hitler was with his own people and they would rise up against him and force him to sue for peace, and the other that the crime was down to a handful of traitors and cowards. The editorial comment had said, ‘Our beloved Führer is impervious to such traitorous attacks. He has God and Right on his side. The enemy will learn this to his cost, as will the perpetrators of this outrage. Everyone who has had any hand in the conspiracy, however small, will be hunted down and receive the fate they deserve.’ It seemed Hitler was decidedly rattled and this latest edition reported that eight very senior officers had been hanged with wire from meat hooks after what Karl guessed was a cursory trial. There had been thousands of arrests and more to come, they were promised, until every traitor had met his just deserts. He wished the plotters had succeeded, but that was a wish he kept to himself. He had no doubt Lieutenant Colonel Williamson, the camp commandant, read every word.

Even so, there were those who considered it their duty to escape and they were busy making plans. Whether they would come to fruition he did not know, but he did not give much for their chances of making it back home, or even off the island. A few, considered trustworthy, were being allowed out to work on farms and building sites. With an English guard, they left the camp in a lorry each morning and returned each evening. He wouldn’t mind doing farm work, even if it was for the enemy. It was better than being incarcerated behind barbed wire and listening to his fellow prisoners grumbling and quarrelling.

He returned from the wash house and took his place in the dining hut for breakfast, after which he asked to see the camp commandant.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles Williamson did not relish his job but it was one that had to be done and, as he was too old for front-line duty, he was glad to do his bit. He was a fair man and treated the prisoners kindly so long as they behaved themselves, but he would not tolerate disruption and did not hesitate to put troublemakers in the ‘Kühler’ as a punishment.

He smiled at Karl from behind his desk. ‘What can I do for you, Sergeant?’ he asked in English.

‘I should like to go out of the camp to work, Herr Kolonel, preferably on a farm.’

‘Worked on a farm before, have you?’

‘Yes. My folk are farmers, that is if they are still alive. I haven’t heard since the Russians bombed my home town over a year ago. We thought the farm was out of range of their bombers, but we were wrong.’

‘I am sorry to hear that, but war is like that. The good, the bad and the indifferent on both sides, suffer indiscriminately.’

‘Yes, Herr Kolonel.’

The colonel pulled himself together suddenly and became businesslike. ‘Normally we wait until prisoners have settled down before letting them out.’

‘I understand.’ He knew they had to be sure it was safe to do so and that meant watching him for troublemaking tendencies. A committed ‘black’ would never be sent on a working party. ‘I have been here a month and I need an occupation.’

‘Very well, I will bear your request in mind.’

‘Thank you, Herr Kolonel.’

‘You speak excellent English. Where did you learn it?’

‘At school and during holidays in England when I was a boy. I came on school exchange visits. My father thought it would be good for me to learn another language and culture.’

‘Where did you stay?’

‘In Cambridge.’

‘Have you kept in touch with your hosts?’

‘No. It was frowned upon.’

‘Yes, I suppose it would be. Very well. Off you go. I will speak to Major Schultz about your request and let you know in due course.’

Karl saluted him and left. Some of his fellow prisoners had refused to salute and when this had been insisted upon gave the Nazi extended arm salute. This did nothing but alert the British authorities to those who would bear watching. He went back to play chess with Otto, which would last until the midday meal. Food was one of the things they could look forward to; their rations were the same as a British soldier received and infinitely better than any they had had from their own forces.

Their own propaganda had told them the British were starving and near to giving up, but he had seen no evidence of it. He had seen the results of bombing while travelling through the country by train when they first arrived, but the population seemed able to absorb it and carry on. Some were antagonistic and didn’t trouble to hide it, but others simply stared at the demoralised prisoners as they shuffled to their trains guarded by British Tommies, most of whom treated them reasonably and shared their cigarettes which made a welcome change from the stinking rubbish called Marhoka they had been issued with.

‘Sei nicht so dumm,’ Otto said when he told him about his request to work. ‘That’s aiding and abetting the enemy and you know what happened to Ernst Schumann and Franz Keitel a week or two ago.’

‘No, what did happen?’

‘They were beaten up.’

‘Who by?’

‘They said it was the English farmhands, but there was a rumour it was some of our own men out to teach them a lesson. They have refused to go out to work since then.’

‘It’s only farm work, for goodness’ sake, and we can earn camp Geld for doing it. It’s better than playing chess all day.’ Camp Geld was token money which they could spend in the camp shop on cigarettes, toiletries and books or a second-hand pair of shoes, things like that, but it was worthless in the outside world.

Otto laughed. ‘Which you do very badly, my friend. That’s checkmate.’

Karl turned his king over. ‘I wasn’t paying attention.’

‘There’s one thing about getting out of camp, you might be able to reconnoitre the lie of the land. It could come in handy.’

‘Not you too?’

‘What about me?’

‘Thinking about escape.’

‘Why not? It gives me something to occupy my mind besides chess.’

Karl laughed. ‘How do you propose to go about it?’

‘I don’t know yet. I will tell you when I do. You interested?’

‘It depends. It would have to have a good chance of succeeding. I’m not risking my neck on some hare-brained scheme that will cost us our lives.’

‘Fair enough. Let’s go and eat.’

Karl mused on the idea of escape as they queued up for meat stew, dumplings, mashed swede and potatoes. The thought of making it home was an attractive one, or it would have been if it hadn’t been for Hitler and the Nazis. It was true, he had been in the Hitler Youth, but that had not been done out of any ideology on his part, simply because all his pals joined and his life would have been made hell if he had not. After school, all he wanted to do was make an honest living in agriculture. He had gone to work for his father until 1938 when he had been called up. The army had become his home. But here? In England? None of it seemed real. Heidi didn’t seem real any more. The last he heard from her was that she was working in a factory in the suburbs of Berlin, but she could be anywhere by now.

When they had arrived in England they had been issued with a printed postcard which said: ‘I have fallen into English captivity. I am well.’ On the other side, by the stamp, it said: ‘Do not write until the POW has notified you of his final address.’ Since coming to this camp he had been allowed to write and tell his parents of his address which went through the International Red Cross in Geneva. They could write no more than twenty-five words which were heavily censored. What could you say in that short space except to say you were okay and being well treated? He had, as yet, received no reply.

He took his plateful of food and his cutlery to a table and sat down beside Otto to eat it.

‘I’m going for a walk this afternoon,’ his friend said.

‘Walk!’ Karl laughed. ‘Where?’

‘Round the perimeter to see if there are any weaknesses in the wire.’

‘I’ve no doubt someone has already done that.’

‘I want to see for myself. Coming?’

‘I might as well, since I’ve nothing better to do and I need to walk off the effects of this dumpling. It’s as heavy as a brick. Nothing like the Knödel Mutti used to make.’

As soon as they had finished eating and washed up their used crockery and cutlery, they set off, strolling unhurriedly towards the wire before turning to trace it round the perimeter of the camp. There was nothing to see beyond the wire except flat fields and a distant village whose church spire rose above a stand of trees. Anyone trying to escape that way would find very little cover.

‘Talking of going home,’ Otto said. ‘Where is home for you?’

‘Hartsveld. It’s a small village halfway between Falkenberg and Eberswalde. My folks are farmers, have been for generations.’ Falkenberg was an important railway junction, while Eberswalde was known for its thriving heavy industry. It was why the area had been heavily bombed and why he was so worried about his family. ‘How about you?’

‘I come from Arnsberg.’

‘Isn’t that near where English bombers breached the Möhne last year?’

‘That’s only British propaganda,’ Otto said. ‘The dams can’t be breached, we were promised that when they were built; the concrete is too thick. All they could have done was make a dint in it. I’ve got a wife who’s working in one of the factories in Düsseldorf. Last I heard she and my parents were safe, but I worry about them.’

‘I worry about mine too,’ Karl said.

‘You married?’ Otto asked him.

‘No, not yet. Engaged though.’

‘What’s her name?’

‘Heidi. I’ve known her for years.’

‘Damn this war.’

‘Amen to that.’

Chapter Two

Jean was about to haul a churn of milk onto the platform just outside the farm gate, ready for the lorry from the Milk Marketing Board to pick up, when a camouflaged truck drew up and stopped. She stood up, pushing a stray lock of hair under the scarf she wore as a turban, and watched as an army corporal, gun slung over his shoulder, lowered the tailboard and jumped down. ‘Mrs Coleman?’

‘That’s my mother.’ Laddie, who followed her everywhere when the boys were at school, was barking at the man and she grabbed his collar. ‘Quiet, Laddie.’ He stopped at once.

‘I’m Corporal Donnington. I believe you asked for POW help.’

‘Yes, we did.’

‘How many do you want?’

Jean smiled. ‘One is enough, Corporal, so long as he’s used to farm work.’

He went to the back of the lorry. ‘You,’ he said, pointing to one of the men sitting inside. ‘Raus.’

A German POW, in a scruffy field grey uniform with a large yellow patch on the leg of his trousers and another on the back of his uniform jacket, jumped down onto the road. The corporal climbed back and refastened the tailboard. ‘Don’t stand for any nonsense, miss,’ he said, banging on the side to tell the driver to move off. ‘We’ll be back to fetch him at six.’ The lorry went on its way delivering more workers to other farms and Jean was left facing her new hand.

He was, she decided, a good-looking man, tall and fair with very blue eyes, a typical Aryan in looks, but with none of the arrogance she had expected. On the other hand, he was certainly not cowed. He clicked his heels together and bowed. ‘Feldwebel Karl Muller, gnädiges Fräulein,’ he said.

She smiled. ‘I am Jean Coleman. Do you speak English?’

‘Yes, Fräulein, I speak English.’ He bent to stroke the dog.

‘Good,’ she said, noting that Laddie appeared pleased to see him, judging by the way he was wagging his tail. ‘I don’t know a word of German and it might be difficult giving you instructions if you don’t understand. Let’s go inside and I will introduce you to my parents.’

Without being asked, he picked up the churn and placed it on the platform for her. She thanked him and led him up the drive, across the yard and into the kitchen. Her mother was boiling pig swill on the range. She had the windows open because of the smell.

‘Mum, this is Feldwebel Karl Muller. He’s come to help us.’

Doris turned to face him. ‘Know anything about farming?’ she asked.

‘I was raised on a farm, gnädige Frau.’

‘I’m Mrs Coleman,’ she said. ‘I can’t be doing with all that German stuff. And what does “Feldwebel” mean?’

‘Sergeant, Mrs Coleman,’ he said with a smile, wondering whether the mess in the pan she was stirring was their dinner. Perhaps the English were starving, after all. She was far from thin though. ‘But Karl will do.’

‘That’s better.’ She lifted the pan off the stove and handed it to him. ‘You can take this out to the pigs for a start. Jean will show you where.’

‘Where’s Pa?’ Jean asked her.

‘He’s having a lie-down in the sitting room. I think he’s asleep, better not disturb him.’

Jean led Karl back across the yard to an outbuilding. ‘Put it on the bench to cool,’ she said. ‘Then I’ll show you round.’

He did as she asked, then followed her outside and was given a tour of the farm buildings. The cowshed was clean and all milking utensils shone. ‘We have six dairy cows and twenty sheep,’ she said. ‘My father was a shepherd in his early days and he still likes to keep a few for wool and meat but most of this area is arable, known for its strawberries. They aren’t growing many of those now; wheat, potatoes and sugar beet are more important. We have a couple of pigs.’ She opened the top half of the pigsty door as she spoke. Two fat porkers started to grunt, expecting their swill. ‘You’ll have to wait,’ she told them, opening the door and ushering them out into the orchard where they could feed on fallen apples. It wasn’t a proper orchard with evenly spaced rows of fruit trees, but a meadow in which different fruit trees were scattered. It housed the pigsty and the hen coops. Beyond it he could see a large pit.

‘Do you and your father work the farm on your own?’ he asked as they continued the tour.

‘My brother used to work with Pa but, like you, he’s a prisoner of war, has been since 1940. Pa has had a stroke and can’t do anything very much.’

‘Do you mean you manage alone?’ he asked in surprise.

‘The villagers give a hand at busy times. We all help each other as much as we can, but there is an acute shortage of labour. I expect it is the same where you come from.’

‘Yes, it is.’

‘There’s a cart, a trap, and a pickup truck in here,’ she said, opening the door so he could look inside. ‘The trap is the best way of getting about, considering petrol is rationed and only allowed for essential business. We have a darling grey pony called Misty to pull it. She spends most of her time in the pasture.’

There was another shed which was a storehouse of strange objects. The walls were hung with garden and farm implements of all kinds – shovels, rakes, sickles, scythes, flails, weed hooks – and iron implements and bits of leather tackle whose original use had been forgotten but which Arthur insisted on keeping. There were bins for chicken feed, bags of seed and trays for storing apples and even an ancient wooden plough. Jars and tins of ointments, powders, scours, linseed oil and turpentine stood on shelves. It had a strange yet familiar smell all of its own. Karl roamed round it smiling and occasionally putting out a hand to touch something.

‘Pa can’t bear to throw anything away,’ she said. ‘And some of it comes in handy.’

‘My father is like that,’ he said. ‘This reminds me so much of home.’

‘What would you be doing if you were at home now?’

‘Much the same as I will do here.’

‘What sort of farm do you have?’

‘Mixed, like this,’ he said. ‘But I do not know what has happened to it and my family since the Russian raids. My older brother, Wilhelm, died on the Polish front very early in the war. I have a sister, Elise, and uncles, aunts and cousins, but I don’t know what has happened to them either. And I have a fiancée. She is in Berlin.’

‘I’m sorry. Perhaps we shouldn’t talk about the war.’ She remembered the regulations for employing German prisoners: there was to be no fraternisation and all conversation was to be kept to giving instructions about the work they were to do. Already she had broken one of them.

‘No, perhaps not.’

She opened the door of the stables. ‘This is the home of Dobbin and Robin, our percherons.’ The horses snickered with pleasure when Karl patted their necks. ‘We are waiting for a tractor, but it hasn’t arrived yet.’ She looked at the shabby uniform he was wearing. ‘Is that all you’ve got to work in?’

‘Yes. When we arrived in England we were issued with a kitbag, a shirt, underwear, socks and toiletries, but no outer clothes.’

‘I’ll find you some dungarees of Pa’s. You’ll get filthy otherwise. And you need some rubber boots.’

She led the way back to the house. That was another rule she had broken; the prisoners were not to be allowed into the homes of their employers. He wiped his shoes thoroughly on the mat before he entered the kitchen. Her mother was not there, but her father was sitting by the hearth, reading a newspaper. He let it drop in his lap and turned towards them. ‘Who’s this?’

‘Pa, this is Sergeant Muller. He is here to help us on the farm.’

‘I told you I don’t want no truck with Jerries. Nasty deceitful people, murderers the lot of ’em.’

‘Pa. They are no more murderers than we are. It’s the war …’

‘I will leave,’ Karl said.

‘You can’t,’ Jean said. ‘Not until you’re fetched. We are responsible for you, I signed a paper to say so. Besides, Pa doesn’t mean it.’

‘Oh, yes I do.’

‘Pa,’ she said patiently. ‘The sergeant is a prisoner, just as Gordon is. I would like to think the German people are treating him well. Think of that, will you? Sergeant Muller is a farmer, or he was, he could be a great help to me.’

‘Then work him hard. Work him damned hard.’ He went back to reading his paper.

Jean smiled at Karl. ‘Come on. There’s work to do.’ She found some dungarees and a pair of boots in the hallway and led the way outside again.

‘I am sorry to be a trouble to you,’ he said.

‘You are not. Take no notice of Pa, he’s just frustrated and angry that he’s so helpless. He still likes to think he’s master though.’

‘I understand.’

‘Your English is very good. Where did you learn it?’

‘At school. Some of us came on exchange visits to England during the school holidays. My father was able to afford it and he said it would be a good thing for me to learn. I seem to have a natural aptitude for languages. The officer who interrogated me said I might be useful as an interpreter.’ He smiled suddenly. ‘In the general confusion they must have forgotten about it because I was sent here, and the only translating I do is for my fellow prisoners.’

Dressed in dungarees over his uniform and wearing a pair of Arthur’s rubber boots, he helped her pour the pig swill into the trough to the accompaniment of noisy squealing as the animals pushed each other to get at the food, then she fetched two scythes from the barn. ‘Can you use one of these?’

‘Yes.’

‘Good because I’m hopeless at it. Pa despairs of me.’ It did not occur to her that she was handing him a weapon.

She led the way through the orchard to the meadow where he began scything the long grass. His movements were rhythmic and assured. She left him to get on with it, while she concentrated on doing the rough edges along the side of the ditch. They had half of it done when Doris arrived with sandwiches and cider for their lunch. They sat under the hedge to eat and drink.

‘This is good,’ he said, biting into an egg sandwich. ‘In Germany we were told the British were starving and ready to surrender.’

Jean laughed. ‘Propaganda. Mind you, rations are pretty tight. We are fortunate in the country, it’s not so easy in the towns.’ She paused, musing. ‘On the other hand townspeople are nearer the shops and can get to them quickly when word gets round there’s something new in that’s not on ration. By the time we’ve tidied ourselves up and caught the bus to town, it’s all gone.’

‘I suppose it is the same for us. Heidi wrote about long lines of people waiting for the shops to open.’

‘Heidi is your fiancée, is she?’

‘Yes. I proposed when I was called up. We planned to marry when I went on leave the next time, but it was not possible. I have not heard from her in over a year.’

‘You are allowed to receive letters in the camp?’

‘Yes. They are censored, of course. But I have had no letters since I came here.’

‘Does she know you are in England?’

‘I do not know. I have written to tell her how to write to me, but …’ He shrugged.

‘She lives in Berlin, you said.’

‘Yes, but she comes from Hartsveld, the same as I do. It is a small village, halfway between Berlin and the Polish border. We have known each other all our lives. She was sent to Berlin to work in a factory at the beginning of the war. I am worried about her.’

‘Because of the bombing?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’m sorry. Perhaps you will hear soon. How long have you been here? In England, I mean.’

‘Just over a month. I was captured in Normandy.’

‘There you are then. No time at all. Letters take a long time, I know. We hear from Gordon, not often but we do hear, though we have no idea exactly where he is, everything is done through the Red Cross. I don’t suppose it really matters, a POW camp is a POW camp wherever it is.’

‘Yes, on both sides of the North Sea.’

‘Mum worries about the air raids.’

‘You have not had any near here, have you?’

‘A few aimed at the airfields, but I meant our raids on Germany.’

‘Oh, I see. But I think perhaps your air force knows where the camps are and do not bomb them. Our aeroplanes do not bomb us because they know where we are.’

‘I hadn’t thought of that. How do they know?’

‘I have no doubt there are ways and means of communicating.’

‘Spies, you mean?’

‘Perhaps, but there are neutral countries; Switzerland, Sweden and Portugal have access to the news on both sides and pass it on.’

‘Can’t you find out about your family that way?’

‘No.’ If he knew any more than that, he was obviously not going to tell her. ‘You are very kind to me.’

‘Why wouldn’t I be? You have done me no harm.’

‘Your father does not agree.’

‘That was Hitler, not you personally.’

He blinked hard. Harsh treatment he could accept, could shrug his shoulders and endure, but kindness touched the core of him and crumbled his defences. He poured more cider from the heavy jug into his mug and drank deeply to cover his embarrassment, then he rose, picked up his scythe and went back to work.

They finished by the middle of the afternoon. ‘A good day’s work,’ she said. ‘I couldn’t have done it without you, at least, not in the time.’

They returned to the farm. Leaving Karl to put the scythes away, she fetched the cows into the byre where they knew their own stalls. ‘Watch that one,’ she told him when he joined her. ‘Gertrude’s been known to kick.’

He patted the cow’s rump and settled himself on the milking stool. ‘Sachte, sachte,’ he murmured to the animal as he put his head into her side and washed her udders before taking them into his hands. ‘You will soon be more comfortable.’

She watched him finish with Gertrude, measure the milk before pouring it into the churn and begin on the next animal, carefully washing his hands and her teats before starting. There was no doubt he knew what he was doing and the routine must have been familiar to him.

They had finished milking, recorded the yield on the Ministry forms and were settling the cows in for the night, when Doris came to tell them dinner was on the table. ‘I have set a place for you, Sergeant Muller,’ she said.

‘I do not think you are expected to feed me,’ he said. ‘Your food is rationed.’

‘It’s a poor do when we can’t give a bite to eat to a working man. You have earned it.’

‘What about your husband?’

‘Oh, pay him no mind. I’ll deal with him. Come and eat. Your transport will be here soon.’

They ate at the big table in the kitchen where he met the rest of the family: Mrs Coleman’s mother, Mrs Sanderson, who lived in her own cottage but had some of her meals at the farm; two schoolboys, who stared at him with unabashed curiosity, one of whom was Jean’s brother, the other an evacuee; and a little girl, called Lily who was the evacuee’s sister. She didn’t live at the farm but with another family nearby. ‘When she’s not at school, she spends nearly all her time here,’ Jean told him.

‘I like being here,’ the child said. ‘I like the animals. And Mrs Coleman cooks better than Mrs Harris.’

‘Shush,’ Doris said. ‘You mustn’t say things like that. Mrs Harris is a very good cook.’

‘Not as good as you.’

Arthur laughed. ‘She’s right there.’

‘And you’ve no call to encourage her, Arthur Coleman. She’ll be telling everyone.’

‘I’ll tell her not to,’ Terry said.

‘And does she do as she’s told?’ Jean asked him. She had taken off the unflattering headscarf and brushed out her hair. It was, Karl noticed, a rich brown.

‘Ma said I was to look after her and she has to obey me,’ Terry said, then turning to Karl. ‘Do you have evacuees in your country Mr German Man?’

Karl smiled. ‘Yes, we do. Just the same. And my name is Karl.’

‘Have you been in many battles, Mr Karl?’ Donald asked.

‘A few.’

‘You’re getting good and beat now,’ Terry said. ‘Monty is a better general than Rommel.’

‘Terry, we won’t talk about the war,’ Jean said.

‘Why not?’

‘Because in this kitchen, at this table, we are at peace with one another,’ she said firmly. ‘Find something else to talk about.’

They went on to discuss the farm work and the meal progressed amicably until the sound of a horn alerted them to the arrival of the camp’s transport. Jean accompanied Karl to the gate.

‘Has he behaved himself?’ Corporal Donnington asked, as he let down the tailboard.

‘He has been a great help,’ Jean told him.

‘So you want him back tomorrow?’

‘Yes, please. If he wants to come.’

Karl clicked his heels together and bowed. ‘I shall come, Fräulein.’ He scrambled up beside his fellows and was gone.

Jean went back indoors and told Terry to take his sister home, then pushed her father into the sitting room and made him comfortable. ‘That wasn’t so bad, Pa, was it? He’s just a man, obeying orders like everyone else.’

‘S’pose so,’ he admitted grudgingly. ‘What did he mek on the work?’

‘He was very good, knew what he was doing. We got the pasture scythed and the milking done in record time. Gertrude didn’t kick out once. I think he’s going to be quite useful.’

‘Still don’t like it.’

‘Needs must,’ she said.

He grunted. ‘And the devil’s driving this one.’

It was a second or two before she understood his reference. ‘Hitler, yes, not Sergeant Muller.’

‘If you say so.’

‘Pa. It’s Hitler and his like who caused all this bother so it’s only right the prisoners should help out when our men are away. Call it recompense, if you like.’

‘All right, I’ll hold me tongue for your sake. Can’t have you getting ill on account of me not able to work.’

‘You will be able to one day, Pa. It just takes time. Now I must go and help Mum. Is there anything you want before I go?’

‘I’ll have the Farmers Weekly and you can bring me the accounts. I want to check on the cost of feed.’

He liked to keep an eye on their accounts even though he knew she was meticulous in keeping them straight. There would be a new expenditure from now on, because they were expected to pay a labourer’s wage for Karl’s work. It wasn’t given to him directly because he had told her he was paid in tokens which he could only spend in the camp shop. She fetched the magazine and the ledgers and pulled a small table up beside his chair and put them on it.

‘All right?’ Doris queried, when she returned to the kitchen where her mother was washing up with Donald’s help. He didn’t like doing it; he maintained it wasn’t a man’s work and he had to be bullied into it. She took the teacloth from his hands and let him escape.

‘Well?’ Otto demanded as he wolfed down Karl’s supper as well as his own. ‘How was it?’

‘Gut. Sehr gut. I spent the day scything a meadow and milking.’

‘What have you discovered?’

‘The farm is a small mixed farm and the family, all except the father, were friendly. They are having the same problems that we have at home with rationing and shortages. The cattle are a bit thin and the milk yield is not what it should be, but Fräulein Coleman put it down to shortage of feed and not having as much pasture as they once had.’

‘Fräulein Coleman?’ Otto queried with a grin.

‘The daughter of the house. She has been trying to run the farm almost single-handed.’

‘Good-looking, is she?’

‘I suppose so; I never thought about it.’

‘I don’t believe that. You haven’t seen a woman, much less spoken to one, for weeks and all you can say is you “suppose so”.’

‘I am engaged to be married.’

‘What difference does that make?’

‘All the difference in the world. Besides, I’d be a fool to try anything on even if I were tempted. I don’t fancy a month in the Kühler.’

‘What else did you see?’ His voice was an undertone, not intended to be heard by anyone else.

‘I saw trees and lanes and farm buildings, a church and a windmill and a lot of flat fields.’

‘No railway lines, no barracks, no airfields, no signposts?’

‘No. I think they must have been removed. Since we have been in England I have not seen a single one. I know the village is called Little Bushey and it’s in Cambridgeshire – that’s a county by the way – but exactly where in Cambridgeshire, I do not know. North, I should think, judging by the terrain.’