4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

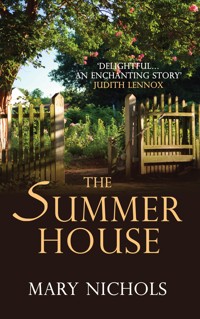

England 1918. Young Lady Helen believes her parents when they say she will never find a better husband than Richard - 'brave, handsome, wealthy, such a charming man and quite a catch'. But when her soldier husband returns to war, Helen begins to wonder just who it is she has married - his letters home are cold and distant - and Helen realises that she has made a terrible mistake. And that's when Oliver Donovan enters her life. They begin an affair that leaves Helen pregnant and alone, and she is forced to surrender her precious baby. Over twenty years pass and a second war is ravaging Europe, but that is not the only echo of the past to haunt the present. Laura Drummond is now caught in a tragic love affair of her own and when she is forced to leave London during the bombings, she turns to the mother she never knew.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 695

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

THE SUMMER HOUSE

MARY NICHOLS

Contents

Title PagePrologueChapter OneChapter TwoChapter ThreeChapter FourChapter FiveChapter SixChapter SevenChapter EightChapter NineChapter TenChapter ElevenChapter TwelveChapter ThirteenEpilogueAbout the AuthorBy Mary NicholsCopyright

Prologue

February 1918

HELENSAWTHE car snaking its way up the hill from her bedroom window. She had been standing there for several minutes contemplating the bleak hillside. The peaks still had snow on them and even on the lower slopes there were a few pockets where it had drifted, white against the blue-black of the hills in winter. The car disappeared for a minute behind an outcrop and then reappeared a little nearer. She knew it was her father’s Humber, even from that distance. Cars were so few and far between in the Highlands of Scotland, the arrival of one was an event. The inhabitants of the village would make a note of it, wonder who it belonged to, where it was going. It had been like that when Papa brought her here. Her great aunt, Martha, had quickly silenced gossip, let it be known that Helen was staying with her to await the birth of her baby while her husband was away fighting in France. Whether they accepted that, Helen neither knew nor cared.

It hadn’t been too bad at the beginning. Before her bump began to show, she had been allowed to go for walks, to go shopping, to take tea with the vicar and his wife, to dream that Oliver would come and rescue her and everything would be all right again. But as the weeks went by and no letter came from him, she fell into a kind of lethargy, a feeling that it didn’t matter what she did, she could not alter anything. ‘There, what did I tell you?’ Aunt Martha said, not for the first time. ‘He’s had his fun and now he’s left you with the consequences. That’s men all over. You didn’t really believe all his lies about being in love, did you?’ The trouble was she didn’t know what to believe and her tears, so copious at the beginning, had all dried up inside her.

No matter how often she went over what had happened, how often she recalled what they had said to each other, she and Oliver, the promises they had made, how safe, almost invulnerable, she felt when she was in his arms, how often she reiterated that Oliver loved her and would stand by her, she could not convince herself any more, let alone Papa and Mama and Great Aunt Martha. They had won.

The car was chugging up the last steep incline now. It would be outside the house in less than a minute and her father would climb out from behind the wheel and come inside. Now her lethargy turned to apprehension. Would he be any less angry, any less obdurate, any less unforgiving than he had been when he left her there? Her father was one of the old school, steeped in class divisions, used to having servants all around him, of shooting and fishing and hunting; of owning most of the village and dictating to its inhabitants, of dictating to her. She had been educated at a girls’ boarding school and a finishing school in Switzerland, then lived at home until a suitable husband could be found for her. Getting a job or doing something useful had not even been considered; daughters of earls did not go out to work and they married young gentleman of their own kind. Looking back, it was strange how she had accepted that so easily.

She turned and looked at the room which had been her prison and her refuge for the last six months. It was a solidly furnished room, matching the solidity of the house: an iron bedstead with brass rails, mahogany wardrobe and chest of drawers, a washstand on which stood a bowl and jug and whose cupboard housed a chamber pot. There was linoleum on the floor and a couple of mats either side of the bed. Compared to the luxury of her room at Beckbridge Hall, with its thick carpet, chintzy covers and bright curtains, it was spartan, but she supposed that was part of her punishment. On the bed lay a packed case. It wasn’t large; she hadn’t brought much with her, just a couple of dresses, underwear, stockings, nightclothes and toiletries. Her aunt had given her dresses of her own to alter to fit as she grew bigger, black and brown in scratchy wool or stiff taffeta. Apart from the one she was wearing she would not take them away with her.

She heard her father being greeted by her great aunt and decided she had better put in an appearance and left the room. At the top of the stairs she paused and looked down. He was taking off his coat and hat. Handing them to Lisa, her aunt’s only indoor servant, he looked up and saw her. Perhaps he had not been prepared for the size of her, but he did nothing to hide the disgust on his face.

She came downstairs slowly, hanging onto the banister and watching her feet, which had almost disappeared beneath the bump of her abdomen. At the bottom she looked up at him. He was tall, his bearing aristocratic, his suit impeccably tailored. His hair was greying at the temples and his moustache was already white. Had it been like that six months before? His grey eyes, she noted, were cold. ‘Papa. Did you have a good journey?’

He looked her up and down. ‘It was damned tiresome. Are you ready to go?’

‘Yes, Papa.’ He had driven himself the whole way and she knew why. Having his chauffeur drive him up would have been easier, but servants talk and the whole object of the exercise had been secrecy. No one in Beckbridge, no one among their acquaintances, none of their relatives must ever learn of Helen’s shame.

‘I’ve arranged an early lunch,’ Great Aunt said, leading the way into the drawing room, where a fire burnt. The drawing room and the dining room were the only rooms allowed a fire, however cold the weather, except the kitchen, of course, which was Lisa’s domain. Helen had often woken to find a tracery of frost on the inside of her bedroom window.

‘Good. You will forgive me for not staying, but it is a long drive. I want to get as far as Edinburgh tonight, if I can. No sense in dawdling.’

No sense at all, Helen thought, but wondered where he was taking her. Not home, not with that bump in front of her to advertise that she was heavily pregnant.

They went into the dining room and Lisa brought in the dishes. Helen ate for the sake of her baby, but the food had no taste. She was glad when the silent meal was over and it was time to put on her hat and a cloak, which concealed her bulging figure better than a coat. Her father took her case from Lisa and put it in the boot. She turned to her great aunt. ‘Goodbye, Aunt Martha. Thank you for having me.’

‘Goodbye, child.’ She pecked Helen’s cheek. ‘Now you remember what I said. When it is over, put it behind you and be a dutiful daughter. Think of your poor Mama and your husband. Pray God, this dreadful war will be over soon and we can all go back to life as it used to be.’

‘Yes, Aunt.’ As she settled herself in the passenger seat, she knew life would never be as it used to be. And she had been a dutiful daughter. That was half the trouble. She had even obediently married the man her parents had chosen for her. It wasn’t that she hadn’t wanted to marry Richard; she had simply been too ignorant to know any better.

Her father settled himself behind the wheel and they set off southwards. ‘Where are we going, Papa?’

‘To London.’

‘London?’ She was astonished.

‘Yes. There is a clinic there where you can have your child. They are known to be discreet. Your baby will be looked after and placed—’

‘Placed! Oh, Papa!’ He hadn’t changed. He was still implacable. She must give up her child. At the beginning she had argued strongly against it, but Aunt Martha had worked on her every day, nagging at her that she must think of what her poor mother was going through because of her wickedness. She could have more babies. What was so terrible about giving one away to a good home, to someone who really wanted a child? It went on and on, like a dripping tap. She would not have given in if she had heard from Oliver, but there was nothing, not a word.

‘Don’t “Papa” me. You may thank your mother you haven’t been thrown out, disowned. That a child of mine should… If Brandon had lived…’ He stopped and shut his mouth tight. Mentioning her brother always put him in a strange mood. Helen had loved her brother and mourned his death as keenly as her parents, but they had never considered that. Immersed in their own grief, they had no time for hers. But Richard had.

It was Brendan’s death that had brought Richard to Beckbridge Hall. He felt he ought to tell her parents of their son’s last heroic fight; the official notification that he had been killed in action didn’t tell them very much. In spite of the sadness of the occasion Richard had impressed not only Helen but her parents with his confident manner and ready smile. They had invited him to stay. He was charming and sympathetic and Helen had liked him, liked the way he turned to her, drawing her into the conversation when her parents might have excluded her. They went riding and walking and talked about anything except the war.

‘Will you write to me?’ he had asked before leaving and she had agreed. Their courtship had been conducted by correspondence, until he had returned to England on much-needed leave and they met again and he proposed. Her parents had been keen on him, telling her she would never find a better husband: brave, handsome, wealthy, such a charming man and quite a catch. She had believed them. Somehow he managed to get an extension to his leave and they had been married straight away. He had returned to France after a two-day honeymoon and all they were left with were letters. How could you make love by correspondence? She had accepted that, looked forward to each rather impersonal missive and the time when they would be together again. And in the meantime she had continued to live at home.

She had helped her mother run the house with its depleted number of servants, coped with shortages of everything including food, alcohol and coal, not to mention her father’s increasingly irascible temper. It was frustration, she realised; he was an ex-soldier and wanted to be out there in the front line, doing his bit, but he was too old and unfit. He was intensely patriotic and would entertain young officers from all the services, offering them baths and meals and often a bed, which would have been all very well in their affluent days before the war, but like everyone else they were having to pull in their belts and such largesse was a struggle to maintain.

‘Louise, I am an earl,’ he said, when her mother protested. ‘We have standards to maintain. Offering hospitality to our boys in uniform is the least I can do, since they won’t let me put one on myself.’

‘Thank goodness for that,’ her mother said. ‘But finding extra food is not exactly easy and finding coal to heat the water for constant baths is a problem.’

‘So it may be, but I hope I shall never be accused of meanness.’

And so her mother, under his thumb as she always had been and always expected to be, continued to welcome officers based in the area. They would stand on the thick Axminster carpet of the drawing room, listening to her father holding forth about how he would conduct the war, sipping gin cocktails and marvelling at everything they could see, from silver goblets to delicate porcelain, bronze busts to portraits of Hardingham ancestors going back generations. Helen would be politely friendly to them all, treating them all alike. Until she met Oliver.

Sitting beside her grim and silent father, the only noise the hum of a well-tuned engine, she allowed herself to drift back to the previous spring. The war was already three years old and the casualties had been horrendous. Even in the quiet backwater of a Norfolk village they could not remain untouched. Besides Brandon there had been others, some killed, some wounded so badly they would never work again, and some whose minds had been turned by the horror. But in spite of that the daffodils still bloomed, the apple trees in the orchard were covered in pink blossom as they were every year, the migrating birds returned. Had they seen the hell that was Flanders? Some of the men who called at the Hall talked about it. Some were silent, too silent. Helen tried to be cheerful, to make everything as normal as possible, but sometimes she needed to escape. At such times she retreated to the summer house.

It stood in the grounds facing the lake; a wooden building with windows on three sides and a small veranda at the front. When they were children – she and Brandon and her cousin Kathy – they would use it as a changing room to put on costumes before going swimming. It had a padded bench along the rear wall in which they kept a croquet set, a couple of cricket bats and some stumps and bails. Now, sitting beside her father, whose concentration on the road before him was absolute, her mind went back there.

She saw again the young man seated on the bench, propped against the corner smoking a cigarette. He was in the uniform of a Canadian captain. Seeing her, he scrambled to his feet and pinched out the cigarette. He was exceptionally tall, but not gangly. His hair appeared dark brown at first, until a shaft of sunlight coming through the window revealed the auburn streaks. He had crinkly, humorous eyes and, unlike so many of the officers who came to the house, he had no moustache. His smile revealed even, white teeth. ‘Lady Barstairs. Am I trespassing? Perhaps I should not be here.’

‘No, it is perfectly all right. Do sit down again.’

Being polite, he would not sit while she stood, so she sat down on the bench and he resumed his seat beside her.

‘I assume you are one of Daddy’s guests.’

‘Yes, I came with a pal, who introduced me to Lord Hardingham. He welcomed me, offered me a cup of tea and a bun.’

‘He likes to do that. He calls it “doing his bit”.’

‘And so he is. Makes us feel at home.’

‘I’m glad.’

‘It’s so peaceful here,’ he said, looking out towards the lake. A pair of swans swam majestically in the middle surrounded by half a dozen mallards. ‘You would never know there was a war.’

‘Have you been out in France?’

‘I was in the attack on the Somme last year. Took some shrapnel in the thigh and got shipped back here to recuperate.’

‘I’m sorry. Does that mean you’ll be sent home?’

‘No. The job’s not finished yet, is it?’

‘You are very brave.’

‘Not brave, Lady Barstairs.’ He laughed lightly. ‘Obstinate perhaps.’

‘You think we can win?’

‘We have to, don’t we?’

‘You sound like my husband.’

‘He’s out there?’

‘In the Flying Corps.’

‘Now there’s a brave man! You wouldn’t get me up in one of those machines for a king’s ransom.’

‘Tell me about yourself,’ she prompted.

‘What do you want to know?’

‘Oh, everything.’ Why she said that she did not know. She didn’t even know his name, nor what kind of man he was, and her parents would certainly not approve of her sitting alone with a man to whom she had not been introduced. They were sticklers for things like that. ‘Start with your name.’

‘Oliver Donovan.’

She offered him her hand. ‘How do you do, Mr Donovan. I’m Helen Barstairs, but you know that already.’

‘Yes. I saw you up at the house, talking to an English officer. My pal said you were the Earl’s daughter. Say, what’s the difference between an earl and a lord? I’ve heard him called both.’

She laughed. ‘A lord is really a baron, a viscount is one step up from that, and from viscount you go up to earl and marquis and then duke, which is the highest. All except the duke are addressed as “my lord”. The duke is “your grace” or “my lord duke”.

‘Oh, I see. And is your husband a lord or something?’

‘No, but as an earl’s daughter I am allowed to keep my title, even if my husband doesn’t have one. Strictly speaking I am Lady Helen. How did we come to be talking about the British aristocracy? You were telling me about yourself. Donovan is an Irish name, isn’t it?’

‘Yes. It was once O’Donovan. My great grandfather went to Canada during the famine of 1846 to start a new life with his family and he dropped the O. He found work on a farm near Ontario, where my grandfather was born. Grandpa grew up and married the daughter of an Englishman, and by the time Pa was born he had a farm of his own. Pa inherited it. He married Mom and that’s when I came along. My folks worked hard to give me a good education and when I left school, I was apprenticed to a motor engineer. I just got through that and was working at the local garage when the war started, so I volunteered. My company looks after the regiment’s vehicles.’

‘What will you do when the war is over?’

‘Go back to it. One day I plan to set up a business selling and servicing motor cars. Believe me, they are the transport of the future.’

‘Are you married?’

‘No.’

‘But you do have a girlfriend?’

He had looked at her a little sideways at that and she found herself blushing. ‘No. That’s something for the future.’

‘You sound optimistic.’

‘Best way to be. Aren’t you?’

‘Sometimes I wonder. There doesn’t seem to be much good news, does there?’

‘Not from the front. When did you last see your husband?’

‘Nearly a year ago now.’

‘You must have been childhood sweethearts.’

‘Why do you say that?’

‘You look so young. You can’t have been married very long.’

‘Less than a year. And I’ll be twenty-one later this year.’

‘A whirlwind romance.’

‘I suppose you could say that. We had only known each other a few weeks when he proposed, but Richard’s father was known to my father and both families were in favour of the match. I hardly had time to get to know him before he went back to France. Sometimes I can’t even remember what he looks like.’ This had been an extraordinary admission and she had no idea why she made it to a perfect stranger, except he did not seem like a stranger. Talking to him was like talking to someone she had known all her life, from whom she had no secrets. She felt she could tell him anything and he would not judge her.

‘It will come back to you when you see him again.’

‘Yes.’

‘No doubt you have letters from him.’

‘Not as many as I did. And they are so impersonal, as if he is afraid—’

‘Everyone out there is afraid.’

‘I meant afraid to open his heart.’

‘Do you open yours to him?’

‘No, I suppose not,’ she said, surprising herself. ‘I don’t think he’d like me being over-sentimental. It’s not how he was brought up, nor me come to that. Stiff upper lip and all that.’ She laughed a little in embarrassment. ‘I don’t know why I’m telling you this.’

‘I suppose because you need to.’

‘Perhaps. Please forgive me.’

‘There’s nothing to forgive.’ He paused. ‘Do you often come and sit in here?’

‘Yes, it’s quiet and I like to look over the lake and dream a little.’

‘What do you dream of?’

‘A world at peace, contentment, children. I was hoping…’ She paused. ‘It was not to be.’

‘They will come.’

‘Do you think so?’

‘Yes, or what are we fighting for? Just before you came, I was sitting here thinking of my folks and what would be happening on the farm at this time of year…’

‘You must be homesick.’

‘I reckon I am, but I’ve enjoyed my time in England, and with people like you and your parents making me welcome, I can’t complain.’

‘You are welcome, you know. Come again, come as often as you like.’

That had been the beginning. They met frequently after that, sometimes in the house when he was with comrades and they would chat as friends do, sometimes walking in the grounds, but most often in the summer house. It was as if they gravitated there without having to arrange it. She would stroll down there and shortly afterwards he would arrive, or it might be the other way around. They talked a lot and before long she realised she knew this man a hundred times better than she did her husband, whose letters had become less frequent and more stilted, as if he were writing to a stranger – which in truth she was, someone he had met briefly and then left behind. It came to her slowly but inexorably that her marriage had been a mistake, that if she had met Oliver first she would never have married Richard. It was a terrible discovery, made more shocking when she realised she was falling in love with Oliver. They were so in tune with each other, almost as if they could read each other’s minds. If they saw each other across a crowded room, their eyebrows would lift and they would smile; it was as if they were alone, as if no one existed for them but each other. And later they would be alone in the summer house.

She tried to deny it, she really did, but it was undeniable. And when he confessed that he felt the same, they fell into each other’s arms. Even then they held back from the brink, but it became harder and harder to deny the physical expression of their love. It grew worse the nearer the time came for him to return to France. She didn’t know how it happened, but one day when they were trying not to talk about the fact that he was soon to leave her, she found herself in his arms and they were stripping the clothes off each other in a frenzy. This time she did not hold back, did not try to stop him. It was gloriously fulfilling and though she knew she ought to feel guilty, there was no time for that, no time for anything but each other.

Those last few days were a revelation. Every minute they could manage, they spent together. He could arouse her so completely she was blind and deaf to everything but his murmured words of love, his dear face, his robust, muscular body. She gave herself to him wholeheartedly, roused him as he roused her, and gloried in it. It wasn’t just the sex; they loved each other.

‘You’ll tell Richard?’ he had asked her the day before he left for France. ‘You’ll tell him you want a divorce?’

‘Divorce?’ Such a thing had never entered her head. She had never given a thought to the future. Now it hit her with the force of a blow to her ribs, taking the wind out of her.

‘How else can you marry me? And you will marry me, won’t you?’

‘I don’t know how to tell him.’ Now she had been forced to confront it, she was left with the guilt, shot through with misery because she couldn’t see a way out. ‘I don’t know how to tell my parents either. There’ll be the most unholy row. And you won’t be here.’

‘I wish I could be. I’d stand by your side and defy the world, but I can’t. I have to go, you understand that, don’t you?’

‘Yes.’ She had cried, oh how she had cried! He had comforted her, held her in his arms and made love to her all over again. She clung to him, not wanting to let him go, but it was getting dark and she knew she had to go back to the house and he to his barracks. In the end she had promised she would tell Richard, but not until he came home. It wasn’t fair to spring that on him while he was away fighting. They said their goodbyes in the summer house and she went back to the Hall, dragging her feet with every step. She had not seen him again.

She did everything she had always done: she was gracious towards the servicemen who came to visit; helped her mother when the servants drifted away, one by one, to more lucrative employment; went to church and prayed for victory; prayed that Oliver would come safely back to her; prayed, too, that Richard would understand when she told him she wanted a divorce. No one in her family had ever been divorced; it was unheard of in their circles and she knew there would be an awful row when her parents found out. In the end it hadn’t been the prospect of a divorce in the family that caused the uproar, but her confession that she was pregnant.

It was teatime and, for once, the three of them were alone in the drawing room. Her mother was presiding over the silver teapot and the bone china cups and saucers; her father was reading a hunting magazine. She suddenly decided to get it over with and blurted out, ‘Mama, Papa, there is something I have to tell you.’ She waited until she had their attention. ‘I’m pregnant.’

‘But you can’t be,’ her mother said, puzzled. ‘Richard has been gone a year.’

‘It isn’t Richard’s.’

‘What?’ her father roared, flinging his magazine on the floor and getting to his feet.

‘I said I’m pregnant.’ She had looked up at him defiantly, but it took all her courage.

‘You dirty little slut! I never thought…’ He stopped because he simply could not get his breath and his face had turned purple. She cringed, half expecting a blow. ‘Whose is it? I’ll kill him. Did he force himself on you? Were you afraid to tell us?’ He was grasping at straws and she could have said she had been raped, but she could not do that, could not deny her love for Oliver.

‘No, he did not force me. We love each other.’

‘Rubbish! You are a married woman. You love your husband.’

‘No. I thought I did, but now I know I don’t. I intend to tell him when he comes home and ask for a divorce.’

‘You will do no such thing. We’ll have to get rid of it.’

Her mother had gasped at that. ‘Henry, you don’t mean an abortion?’

‘Yes. I’ll find someone willing to do it.’

‘No, you will not!’ Helen had screamed at him. ‘I want this baby.’

‘You can’t possibly mean to keep it,’ her mother said. ‘It’s unthinkable. What will you tell Richard? What will everyone say?’

She had become reckless. ‘I don’t care what people say. I shall explain to Richard and when Oliver comes back, we are going to be married.’

‘You can’t, you already have a husband.’

‘Oliver?’ Her father picked up on the name. ‘Who is Oliver?’

‘Captain Oliver Donovan.’

‘Where did you meet him?’

‘Here. He’s one of your protégés, a Canadian.’

‘And that’s how he repays my hospitality, is it? I shall go to his commanding officer and have him kicked out…’ He was pacing the drawing room floor, so agitated she was afraid he’d have a heart attack.

‘Henry, I don’t think that’s a good idea,’ her mother said softly. ‘We don’t want to draw attention to Helen’s plight, do we? Perhaps she should go away, she could stay with my aunt in Scotland. We can always say she has gone to be near Richard.’

‘He’s in France,’ Helen reminded her.

‘Then for the purpose of saving your good name, he’ll have to come back,’ her father snapped.

‘If you think I am going to get into bed with him and then pretend the child is his, Papa, then you are mistaken. I will not deceive him.’

‘You already have.’

‘I’m sorry for that, I never meant to hurt him, and in any case I do not think he will be too upset. I don’t think he loves me.’

‘And what about Richard’s parents? His father is a judge, for goodness sake. Have you thought of anyone else besides yourself? To think a child of mine should behave in such a wanton and depraved manner is more than I can stomach.’

‘It wasn’t wanton or depraved. Oliver and I love each other. He will accept his child. He’ll be pleased.’

That was more than her father could take. He ordered her to her room just as he had when she had been naughty as a child, and her meals were brought to her by the chambermaid. After three days of solitary confinement, her mother came to her. She had been writing to Oliver, but put her pen down and covered the sheet with blotting paper.

‘Helen, your father and I have made the arrangements.’ She sat down heavily on the bed. ‘You are to go and stay with my Aunt Martha in Scotland until it is time for the child to be born, and then you will go into a private clinic. You haven’t told anyone about this, have you?’

‘No.’

‘What about Kathy? Does she know?’

Her cousin Kathy lived with her parents in Beckbridge Rectory. She and Kathy had gone to the same boarding school, and as schoolgirls had giggled over shared secrets and later had laughed together over the different young men who came calling. Until Richard came along. She supposed it was bound to make a difference to their relationship; she was suddenly a married woman and Kathy must have felt left out. They had remained friends, though not so close, but even that had come to an end when Kathy had come upon her and Oliver in the summer house. It had precipitated a terrible quarrel; dreadful things had been said, mostly about the effect it would have on Richard if he found out. Helen had tried explaining, but Kathy wouldn’t listen and had gone home in a huff. It was then Helen realised that Kathy was in love with Richard. They hadn’t spoken since.

‘No, I’ve told no one.’

‘Good. And no one will be told. If you want to correspond with Kathy, you can, but you will do it through us. And you will say nothing of your disgrace, do you hear? I could not bear it to become common knowledge.’

‘Great Aunt Martha?’

‘She knows, of course. But as far as her friends and neighbours are concerned, you are staying with her to await the birth of your husband’s baby.’ Mama had smiled grimly. ‘Not that you will be expected to do much socialising; Aunt Martha is old-fashioned. In her day, pregnant women were kept hidden away.’

‘And I am to be kept hidden.’ The prospect was not a happy one, but given the atmosphere at home, she would be glad to get away. She would spend her time knitting and sewing for the baby and writing long letters to Oliver. He might even manage to get leave and come to see her, though she realised that was unlikely until the war ended. She prayed it would be soon; if Oliver came back before Richard it would make it so much easier, if only because she would have an ally. ‘But what happens when I return home? You can hardly hide a baby.’

‘You won’t be bringing it home. It will be adopted.’

‘No! I will not agree to that.’

‘Helen, do not be obtuse. You know you cannot suddenly produce a baby when everyone knows your husband is away in France and has been there over a year. And what do you think he will say when he comes home?’

‘Then I shall stay away. Find somewhere else to live.’

‘How? What will you live on? You have never wanted for anything in your life, never done a hand’s turn of work, and you certainly would not have the first idea how to go about bringing up a child. I can promise you Papa will not help you and I dare not go against him. When it is all over, you can come back here as if nothing had happened. We will none of us mention it again.’

‘And keep it secret from Richard, I suppose,’ she said bitterly.

‘It would be best.’

She knew she was getting nowhere and was tired of arguing. It would be a few more weeks before she began to show and by that time Oliver would have replied to her letter, might have managed some leave. But she hadn’t been given even that respite; she had been packed off to Scotland the very next day.

Her father was drawing into a petrol station. She watched while he got out, spoke to the attendant who came out to serve him, paid the man and returned to the car. Then they were on their way again, without either having spoken. They stopped for lunch at a hotel. The conversation was confined to polite enquiries about what she would like to order. Was it going to be like this the whole way? Could she get through to him if she tried? But what was the use? Aunt Martha had been right; Oliver had deserted her. Either that or he was one of the many casualties of war, and without him she could not hope to bring up a child. It didn’t matter; she didn’t feel anything for it. It was an uncomfortable lump that wouldn’t let her sleep at night, that made her want to go to the lavatory every five minutes. She would be glad to be rid of it. So she told herself.

They stayed in Edinburgh overnight. The hotel was luxurious, the bed far more comfortable than the hard mattress at Great Aunt Martha’s, but it did not help her to sleep. They left very early the next morning and the pattern of the previous day was repeated. Helen tried to make conversation, to remark on how much warmer it was as they journeyed southwards. She wondered if they might take a little detour to go to Beckbridge, she would have liked to see her mother. But of course Papa would not do that. She could not go home until her figure was back to normal. It was late at night when they entered the suburbs of London and it was then she began to wonder where this hospital was. It was another half hour before her curiosity was satisfied.

They drew up outside a dingy red-brick building in a part of the city she had never been in before. Her father got out and fetched her case from the boot. ‘Come along,’ he said. ‘I want my bed even if you don’t.’

Stiff with sitting for so long, she clambered awkwardly from her seat and followed him up the steps. A plaque on the wall announced it was the St Mary and Martha Clinic. They entered a gloomy hall, lit by gaslight. There was a desk and a bell, which he picked up and rang vigorously. It was answered shortly by a young girl in a grey uniform to whom he gave the name of Lord Warren and told her the matron was expecting him. While she was gone he turned to Helen. ‘You are to be known as Mrs Jones, please remember that.’

She nodded, not caring what she was called. She didn’t like the smell of the place, nor the strange cries coming from its interior. For the first time she began to be afraid of the ordeal to come. ‘Are you going to leave me here, Papa?’

‘Yes, of course. What else did you expect? I’ll go to my club tonight and then I’m going home. When I hear from Matron that it is all over, I shall return for you.’

If he had been going to say more, he did not, because Matron was hurrying towards them. ‘Do not address me as Papa,’ he murmured.

Matron was fat. She wore a navy blue dress and a wide belt that seemed to cut her in two. Her hair was scraped back beneath a starched cap. ‘My lord, please come this way. Would you like some refreshment before you go?’ She ignored Helen, who trailed behind them, weariness in every bone of her body, the fight gone out of her. She longed for her mother.

The matron conducted them to an office where the particulars of her pregnancy were noted. She had been sick early on but otherwise had kept well. The doctor she had seen in Scotland had said there was no reason to expect complications; she was young and well nourished.

‘And the expected date is the middle of March, I understand?’

‘Yes.’

A servant arrived with a tea tray but Helen was not offered any of it. She was handed over to a nurse to be conducted to her room. She turned back to her father, wanting to say goodbye, had his name on her lips when she remembered his stricture that she should not address him as Papa. He had not said so but she guessed he was pretending she was a servant for whom he felt some responsibility. For a second her spirit returned. She straightened her back. ‘Goodbye, my lord. Please remember me to her ladyship.’ Then she followed the nurse.

Normally patients would not arrive so far in advance of their due date, but her father had not wanted to risk her giving birth in Scotland or on the way to the clinic. She had her own room and was expected to remain in it and take her meals in solitary splendour. That palled after the first day and she asked to be given something useful to do. She was allowed to help the other patients, those who had already given birth, taking them their meals, fetching glasses of water, talking to them. They were mostly young, unmarried and ill-educated. Some had even been ignorant of what was happening to them until their bodies began to swell. Some had been raped, some abused by male relatives. She was appalled. Not one seemed to have a loving partner and not one expected to take their infants out with them. And the nurses were far from sympathetic. What had her father – the man who had given her life, had nurtured her through childhood, a loving, if strict, disciplinarian – brought her to?

Helen’s baby, a lovely dark-haired girl, was born in the early hours of the morning of the fifth of March, ten days earlier than expected, and put into her arms. She fell instantly in love with her. The fact that Oliver had deserted her didn’t seem to matter any more. She wanted to keep her. She helped bathe and dress her in the little garments she had made for her and was allowed to give her a feed. The pull of the baby’s mouth on her breast set her weeping again and strengthened her resolve. This tiny child was hers and she’d be damned if she would give her up. She would call her Olivia.

It was a resolve she was not allowed to keep. Her parents came the very next day to fetch her home. She was so pleased to see her mother she burst into tears and held out her arms. Her mother hugged her. ‘Hush, my child, it’s all over now.’

‘No, it isn’t. Look at her, Mama.’ She pointed to the crib beside the bed. ‘Just look at her. Tell me you don’t feel something. She is your grandchild, for God’s sake.’ Instead of looking at the baby her mother looked at her father, but he was sternly implacable. Helen reached out and plucked Olivia from her cot and cradled her in her arms. ‘Look, Mama. See what huge blue eyes she has. And she has such a strong grip. Look.’ Helen lifted her hand to show the baby’s hand closed tightly around her little finger. ‘She is mine, my flesh and blood. I love her with all my heart. I cannot give her up. Don’t ask me to, please.’

‘Helen, don’t be silly,’ her father said, while her mother looked as if she was going to cry. Unable to bear the pain she knew her daughter was experiencing, not daring to share it, she turned away.

The nurse who had helped at the confinement entered the room. ‘Everything has been arranged, sir. Doctor Goldsmith would like to see you in Matron’s office before you go. There are one or two details he needs to go over with you. I’ll take the child.’ She went to take the baby from Helen.

‘No, you don’t!’ Helen screamed at her. ‘You can’t have her. She’s mine.’

‘Helen,’ her mother begged. ‘Please…’

‘Tell them. Tell them I’m going to keep her. Tell them I withdraw my consent.’ She was hanging onto the child so tightly the infant began to wail and the nurse looked helplessly at her father.

He strode over and forcibly prised open Helen’s arms so that the nurse could take the child. Helen, blinded by tears, saw the blurred form of the nurse disappearing through the door. Her father followed, leaving Helen sobbing uncontrollably.

‘Darling, please don’t take on so,’ her mother said. ‘You know it isn’t possible to keep her. What’s so terrible about giving her away to a good home, to someone who really wants a child and can’t have one of her own? One day you will have children with Richard and they will be welcomed. Now be a good girl and let me help you dress. I’ve brought one of your favourite dresses, the blue and grey striped wool. It will be nice and warm. We don’t want you to catch a chill in the car.’

Helen got out of bed and began to dress like an automaton, then flung her few possessions in her case, strangely empty without the tiny garments which had been taken away with her baby. While they waited for her father to come back, she wandered over to the window and looked down on the busy street. Two storeys below her, a woman came out of the entrance carrying a baby. The infant was wrapped in the shawl Helen had knitted for her; even at that distance she recognised it. She beat her fists on the glass and yelled defiance until she was forcibly restrained and given a strong sedative. Under its influence she stumbled out of the hospital, flanked by her mother and father, and got into the back of the car, but she was not so subdued that she didn’t vow that one day, however long it took, she would find her daughter again, and then nothing on earth would part them.

Chapter One

1940

THE YOUNG MAN in the hospital bed opened one eye and quickly shut it again. A half smile played about his features. Nice features, Laura thought, unblemished by the terrible burns that many downed pilots had to suffer, but he could do with a shave. And he was so young. She leant forward and smoothed the blond hair from his brow as his eyes opened and looked straight into hers. She smiled and dropped her hand.

‘This must be heaven,’ he murmured, grinning at her. ‘And you are my guardian angel.’

‘No, you are still in the land of the living. And I am certainly no angel.’

‘You look angelic enough to me.’ Beneath the starched cap, she had dark, not quite black hair, swept back and up from a distinct widow’s peak. She had warm amber eyes in an oval face with high cheekbones, a straight nose and a firm mouth. Her figure was as good to look at as her face, cinched into a tiny waist by the wide nurse’s belt. Her legs, even in stout, flat-heeled shoes, were long and shapely.

‘Have you met many angels?’

‘Can’t say I have.’

‘There you are then; not qualified to judge.’

He looked around him. There were twenty beds in two straight lines, each one containing a patient. A locker beside each held a jug of water and a glass; some had a vase of flowers, others a photograph. Some patients were sitting up reading, some had headphones and were listening to the wireless, others lay still and almost lifeless. A few were restless and being calmed by nurses. The rows of windows were heavily crisscrossed with sticky tape. Outside the sun shone, making the same criss-cross shadows on the beds and across the polished floor.

‘Hospital?’

‘Yes. The Royal Masonic, Hammersmith. Part of it has been taken over by the RAF. There’s a doctor here who knows a bit about burns.’

‘Burns?’ He lifted a bandaged hand and touched his face.

‘No, only your hands and they will heal. You won’t need skin grafts or anything like that.’

‘Thank God for that. Can’t have my boyish good looks ruined.’

‘No, you’re still the same handsome devil you always were.’ She smiled. ‘You were lucky.’

He grinned. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Staff Nurse Drummond.’ She leant over to help him sit up, then picked up a cup of water and put it to his lips. He drank thirstily before sinking back onto his pillow.

‘I meant your Christian name.’

‘Laura.’

‘Laura,’ he murmured. ‘I like that, it’s pretty.’

‘Don’t let Matron hear you call me that. I’m Staff Nurse and don’t you forget it.’

‘Staff Nurse is too starchy for someone as pretty as you are. Are you married?’

‘No, but I will be tomorrow.’ Tomorrow. She could hardly believe her wedding was only a day away.

‘Congratulations! He’s a lucky dog. Airman, is he?’

‘Yes, a squadron leader.’

In normal times this would be her last day at work; a man like Bob would not expect his wife to work and, in any case, the authorities disapproved of married nurses on the grounds that they could not look after patients properly and run a home at the same time. But these were far from normal times and women with no family ties were expected to work. She would have a week off, the same as Bob, and then return to duty, living at home until they could find a house of their own. It really would make no immediate difference to her working life, except for the gold band on her finger and the allowance she got as Bob’s wife. The young airman told the whole ward about the wedding and she went off duty with the good wishes of the patients ringing in her ears.

At the door she was stopped by Matron. ‘Staff Nurse, a word if you please. Come with me.’

Mystified, Laura followed her to her office and stood uncertainly as she flung open the door and gestured her inside. The room was packed with her colleagues, who clapped enthusiastically. ‘We wanted to wish you good luck,’ Matron said, bending down to retrieve a package from behind her desk. ‘A little something for your bottom drawer to show our appreciation of your sterling service.’

Laura, surprised and delighted, took the parcel and to cries of, ‘Open it!’ she undid the ribbon. It contained a pair of sheets and pillowcases.

‘Thank you, thank you so much,’ she said, overcome by their generosity.

Dr Gibbs produced a bottle of sherry. A strange collection of glasses was found and a toast drunk. By the time she left an hour later, she was surrounded by a warm glow of goodwill, helped on by the sherry. Clutching her parcel, she set off for the Underground and home.

It was a balmy evening; the sun was just going down behind the rooftops, throwing long shadows across the road. It could have been any evening in peacetime, except for the barrage balloons swaying lazily overhead, the sandbags stacked round doors and the taped-up windows. And the uniforms. Almost everyone seemed to be wearing one of some kind: khaki, navy, air force blue or the green of the Women’s Voluntary Service. There was even a Boy Scout in a khaki shirt and shorts, cycling down the road, pedalling for all he was worth.

Laura took the Underground to Edgware and walked the rest of the way to her home in Burnt Oak. She let herself in and carefully drew the curtain over the door before switching on the light and hanging up her cloak and gas mask on the coat stand in the corner.

It was a typical three-bedroomed semi-detached house. The stairs went up on the left and there was a narrow passage on the right with two doors. The first led into a sitting room, which contained a three-piece suite, a table with a lace cover, on which stood a vase of flowers, a glass cabinet for displaying ornaments, a bookcase each side of the fireplace and a mirror over the mantelpiece. It had a square of carpet surrounded by lino. The second door led to the dining room. That had a dining table and chairs, a sideboard and a cupboard in the chimney alcove. Beyond that, facing her, a third door led to the kitchen. Here, her mother was putting an iron over her wedding dress.

Unlike Laura, who was tall and slim, Anne Drummond was tiny, a little plump and she had fine blonde hair, very different from Laura’s dark locks. ‘You’ve done that once already,’ Laura said, kissing her cheek.

‘I had to press mine so I thought I’d give it another going-over. Go and hang it on your wardrobe while I make tea.’ It had proved almost impossible to buy clothes or even the materials to make them and Anne’s dress was a blue silk she had had in her wardrobe for ages and hardly worn. It was outmoded but they had altered it to bring it up to date, something everybody who could use a sewing machine and a needle was doing. Coats were being made into jackets, dresses into blouses, men’s trousers into boys’ shorts.

‘Did you manage to order the flowers?’

‘Yes, but they couldn’t guarantee what they’d be. They said they’d do their best.’

‘That’s all right. Just so I have some. They gave me some bed linen at the hospital and the woman who puts the Hammersmith emblem on all the hospital sheets and pillowcases embroidered our initials on them. Wasn’t that a lovely thought?’

‘Yes. Put them in the front room with the other presents. There’s more come today. Everybody in the street seems to have brought something. And our friends at the church.’ Anne was a regular churchgoer, though Laura, being so often on shift work, did not attend so often. She had gone the previous Sunday to hear the banns read for the last time.

‘Oh, how kind everyone is. I didn’t know I had so many friends.’

Her mother had been shocked when Laura told her Bob had proposed, saying she hardly knew him, that he was a pilot and could be shot down at any time, making her a widow before she had had time to be a wife, that he came from a completely different background and she could not see Bob’s hoity-toity parents agreeing to it. Laura had countered that she had known Bob for six months but it seemed like forever, and as for the war, everyone had to take risks and seize what happiness they could when they could. And as for Bob’s parents, she wasn’t marrying them. It was said confidently, though she did wonder how she would fit in with his lifestyle. She had always watched the pennies, made her own clothes and never had a fire in her bedroom; economies like that were second nature to her, and nowadays everyone was being urged to do the same, but did that include a wealthy baronet and his wife? What was the point of worrying about it? ‘Bob loves me and I love him,’ she had said. ‘Please, please be happy for me.’

Her mother had pulled herself together and smiled. ‘If you are happy, then I’m happy.’

‘That’s all I ask. It won’t be an elaborate wedding; it wouldn’t be right, what with the war and everything. I’ll buy some material and make myself a dress.’

‘You can have my dress. I kept it for you.’

‘Did you? I didn’t know that. Will it fit?’

‘We can alter it.’

Laura had hugged her impulsively. ‘You’re the best mother in the world, you know that, don’t you?’

‘Oh, give over.’

On her way upstairs, she went to look at the gifts. They were small, inexpensive presents for the most part and most were useful things for the home. Besides the sheets and pillowcases she had been given by her colleagues, there was a glass fruit bowl and six little dishes; a set of fruit spoons; a matching teapot, milk jug and sugar bowl; two vases; a tablecloth; more pillowcases; two towels and a framed picture. She was overcome by how generous everyone had been. All carried cards of good wishes, and Laura had made a list so that she could write and thank them all. In contrast, there was a huge punchbowl and glasses from Bob’s sister, whom she had yet to meet. It was kind of her, but Laura wondered when she would ever use it. There was nothing from his parents, though they had not gone so far as to boycott the wedding, sending a formal acceptance of the invitation. She supposed they had given their present to Bob.

She went upstairs and hung the dress on the wardrobe door, standing back to admire it. Mum had had to shorten it for her own wedding, but she had kept the spare material. They had joined it back on with a wide band of lace and used more lace to trim the bodice, then narrowed the wide tops of the leg o’ mutton sleeves. Laura was thrilled with the result. The veil was spread over the mirror of her dressing table and her shoes were standing side by side beneath it. She smiled, picturing Bob as she walked up the aisle towards him. He would be in uniform, of course, his cap tucked under his arm, smiling at her with love in his eyes. And Steve, as fair as Bob was dark, would be beside him with the wedding ring in his pocket. Already her nerves were beginning to tingle.

Still smiling, she returned to her mother in the kitchen, where a batch of newly baked sausage rolls cooled on a wire tray. Even the butcher had been kind; as well as the sausages, he had found them some ham, sliced very thinly to make it go round. And her mother had managed to get a little dried fruit and a couple of eggs and made a cake. It was only eight inches across and two inches deep but they hid it under an iced cardboard cake borrowed from the local baker.

They had barely sat down to eat when the siren wailed. Anne got up, covered the sausage rolls and put them on a shelf in the larder, then set about gathering up everything they needed for a night in the Anderson shelter: blankets, pillows, a torch, some matches, a packet of sandwiches and a Thermos flask of tea. She also grabbed a little attaché case in which she kept their birth certificates, her marriage licence, the rent book and a few precious snapshots and mementoes. ‘If we are bombed out, we’ll need to prove this is our house and we are entitled to be re-homed,’ she had told Laura, who had never seen the case before the raids started.

In spite of the warmth of the day that had gone before, the shelter struck them as dank and airless. Seven pounds it had cost them for a few sheets of curved corrugated iron and some bolts. They had made a big square hole in the back garden lawn and assembled it, covering it with the turf they had dug out, though it didn’t go all the way over the top. After putting a couple of deckchairs and an oil lamp inside, they had left it and there it had stood, unused, mocking them for months when the threatened air raids failed to materialise. Now it was in constant use.

They made sure the door was secure before lighting the lamp and settling down in the chairs. Anne had brought some knitting and Laura a book to read. But far from concentrating on those, their ears were attuned to the noises outside. They could hear the distant hum of aircraft, though whose they were they could not tell, and the sporadic sound of an ack-ack gun, and then, far away, a kind of crump. None of it sounded very close, but it was more than they had heard before.

Anne unscrewed the Thermos and poured two cups of tea. ‘Might as well have this while we can.’

Laura sipped hers reflectively, wondering if Bob was in the skies above her. She never thought of her own danger, only that of the man she loved. ‘Please God, bring him back safely,’ she prayed over and over again. Due to the losses, some from sheer exhaustion, Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding had ruled that pilots must have a minimum of eight hours off duty in every twenty-four and a continuous twenty-four hours off every week, which meant they could leave the base. Bob always made for Burnt Oak and Laura. Sometimes they went dancing, sometimes to the pictures if it was an evening or, if it was daytime, they would walk in the park or listen to a lunchtime piano recital, or take a meagre picnic into the country. They had not been able to see each other quite so often lately; he had been in the air almost every day, at night, too, if the weather was clear enough for bombers to see their targets, but he phoned when he could to reassure her he was in one piece and couldn’t wait to make her Mrs Rawton. And tomorrow it would happen.

She had asked Bob about his sister being a bridesmaid, but he had said she wouldn’t be able to get leave from the WAAF and so Nurse Bradley, one of Laura’s colleagues, was going to be bridesmaid instead, and she was providing her own dress. Her mother was going to give her away. Bob’s parents thought it was a strange arrangement but Laura would not go searching for male relatives she hardly knew to take on the role. Everything was ready but the nearer the time came, the more nervous she became.