Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

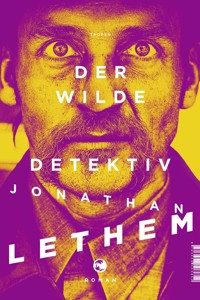

'A nimble and uncanny performance, brimming with Lethem's trademark verve and wit' Colson Whitehead, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Underground Railroad Phoebe Siegler first meets Charles Heist in a shabby trailer on the eastern edge of Los Angeles. She's looking for her friend's missing daughter, Arabella, and hires Heist - a laconic loner who keeps his pet opossum in a desk drawer - to help. The unlikely pair navigate the enclaves of desert-dwelling vagabonds and find that Arabella is in serious trouble - caught in the middle of a violent standoff that only Heist, mysteriously, can end. Phoebe's trip to the desert was always going to be strange, but it was never supposed to be dangerous... Jonathan Lethem's first detective novel since Motherless Brooklyn, The Feral Detective is a singular achievement by one of our greatest writers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 345

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE FERAL DETECTIVE

Also by Jonathan Lethem

NOVELS

Gun, with Occasional Music

Amnesia Moon

As She Climbed Across the Table

Girl in Landscape

Motherless Brooklyn

The Fortress of Solitude

You Don’t Love Me Yet

Chronic City

Dissident Gardens

A Gambler’s Anatomy

NOVELLAS

This Shape We’re In

SHORT STORY COLLECTIONS

The Wall of the Sky, the Wall of the Eye

Kafka Americana (with Carter Scholz)

Men and Cartoons

How We Got Insipid

Lucky Alan and Other Stories

First published in the United States in 2018 by Ecco, an imprint of

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd, New York.

Published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2018 by

Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jonathan Lethem, 2018

The moral right of Jonathan Lethem to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 748 2

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 749 9

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 750 5

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

In memory of

MICHAEL FRIEDMAN

ARDEN REED

DAN ICOLARI

Only too well do I know the Yahoos to be a barbarous nation, perhaps the most barbarous to be found upon the face of the earth, but it would be unjust to overlook certain traits which redeem them. They have institutions of their own; they enjoy a king; they employ a language based upon abstract concepts; they believe, like the Hebrews and the Greeks, in the divine nature of poetry; and they surmise that the soul survives the death of the body. They also uphold the truth of punishments and rewards. After their fashion, they stand for civilization much as we ourselves do, in spite of our many transgressions. I do not repent having fought in their ranks against the Ape-men.

—JORGE LUIS BORGES, BRODIE’S REPORT

Granted there is no artifice here, no trickery, what motive has this man for having no motive?

—DAWN POWELL, TURN, MAGIC WHEEL

1

I WAS TWENTY MINUTES LATE FOR MY APPOINTMENT WITH THE FERAL Detective, because I drove past the place twice. In daylight, broad flat morning, in a rental car with GPS that only sort of betrayed me. It was the feeling the place inspired that betrayed me worse. The feeling, specifically, that it was a place for driving past, and so my foot couldn’t find the brake. White stucco, with redwood-clad pillars and a terra-cotta tile roof. A deck ran around the second floor, accessible from stairs on the parking lot side. The windows were all barred.

The signage at the various doors was either crappy plastic or just banners printed vertically, nailed through eyelets to the pillars. One said only TATTOO, another SPA. Upstairs, WARRIOR SUTRA BODY PIERCING. In the window of SPA, in front of closed curtains, neon bulbs in red and blue said OPEN. I assumed I knew what spa meant in this case. It was nine on a Saturday morning, January 14, 2017. Or nine twenty, since I was, as I said, late. It seemed impossible to be late for an appointment with anything at a building such as this.

To make an appointment here was to have dropped through the floor of your life, out of ordinary time. You weren’t meant to be here at all, if you were me.

Having missed the destination, I drove a ways on Foothill Boulevard before figuring it out. The malls and gas stations and chain restaurants took on the quality of a single repeated backdrop, such as Fred Flintstone would motor past. Space was different here. I doubled back and slowed. The building wasn’t dark, exactly—nothing could be, in this glare. But it had a warty density that made it easy to miss.

The problem was also the immediate surround. Beyond the parking lot, a wide-strewn trailer park. On the right, behind cyclone fence, a tundra of pits and heaped hills of gravel, in a lot the approximate size of Central Park. Maybe I exaggerate. I do. Half the size of Central Park. In this wasteland the building seemed fake. It claimed a context where none was possible. I mean, human beings, ones you’d want to be or know. The power that had caused me to drive past was more than unappealing. The building made you aware of mental blinders. To park your car here was to not be who you thought you were. Maybe I wasn’t now.

Plus, the blue was killing me. I don’t mean the blues, as in the white girl blues. (I did have those, though I’d never resort to such bogus shit aloud.) It was the blue of the sky that was killing me, that and the way, across the street, with no sense of proportion or taste, snow-capped peaks argued intricately with the flat galactic blue. Beneath the peaks, white bandwidths of fog clung to the contours of rock. There was nothing like these in the sky itself.

If I stared at the places where the blue met the white, it freaked me out. It was a thing you only saw in the movies, with actors costumed as dwarves running up a CGI mountain, except here there was no black frame, no exit sign floating in the periphery. Just the blue. I considered the word unearthly and then discarded it as stupid. This was the earthly, precisely. I parked in the lot behind the building and looked for suite number eight.

I had to go up the stairs to find it. The second-story deck put me in a new relation to the expanse of trailers, the suburban vacuity beyond. It didn’t solve the mystery of what was tucked inside those gravel arroyos, though, or how the white fluff could be stuck to the mountains when there wasn’t a cloud in the sky.

Lady, you did this. You went west. Now, suck it up. I knocked.

2

IN CASE IT ISN’T OBVIOUS, THERE’S A DETECTIVE IN THIS STORY. BUT I’M not it. I had myself halfway cast in the role when I got on the plane, but no. Sorry. Then again, the story does involve a missing person, and it could well be me. Or you or practically anybody. As he said to me once, who’s not missing? He was prone to these low-ebb oracular remarks. To my surprise, I learned to like them.

3

A VOICE BEHIND THE BRASS #8 CALLED, “IT’S OPEN.” I PUSHED IN. THE usual law of glaring sunlight applied, so I was blinded in the gloom. There wasn’t a foyer or waiting area, let alone a secretary screening his appointments. I’d lurched into the so-called suite, a large, cluttered, murky space that grew darker when the voice said “Close the door” and I obeyed. In the instant I’d had to discern outlines, I made out the boat-sized desk, the figure behind it, the shapes along the walls, all inanimate. No other bodies waiting in ambush, I felt reasonably sure. I could be back through the door before he’d be around the desk. I had pepper spray and a tiny compressed-air klaxon horn in my purse. I’d never used either one, and the klaxon was maybe a joke.

“Phoebe Siegler?” The only lamp in the room sat on the desk. All I saw was jeans and boots. The lamp had for company only a landline, a heavy black office phone. No computer.

“Sorry I’m late,” I said, just to say something.

He dropped his feet from the desk and rolled forward in his chair and my eyes adjusted first to find his worn red leather jacket, cut and detailed like a cowboy shirt, with white-leather-trimmed vest pockets and cuffs. The leather was so stiff and dry, it was as if a cowboy shirt had been cast in bronze, then spray-painted. An absurd jacket, though I came to take it for granted. More than that, as an emblem. I’ve still never seen another like it.

Above, his big head came into the light. His eyes were brown under bushy, devilishly arched brows. His hair streamed back from his wide forehead, and his sideburns were wide and beardy enough to seem to stream from his cheeks too. Like his whole face had pushed through a gap in a web of hair, I thought absurdly. Where the burns stopped he needed a shave, two days’ worth at least. He resembled one of those pottery leaf-faces you find hanging on the sheds of wannabe-English gardens. His big nose and lips, his deep-cleft chin and philtrum, looked like ceramic or wood. Somehow, despite or because of all of this, I registered him as attractive, with an undertow of disgust. The disgust was perhaps at myself, for noticing.

A minor nagging mystery for me had always been what did Meryl see in Clint anyhow? I think I caught that movie on cable when I was eleven or twelve, and I’d found him only baffling and weird. So maybe that was the mystery I’d come all this way to solve. Realizing I find someone attractive is often like this for me, a catching-up of the brain to something as remote as if on some faraway planet. I guess I could cross it off my bucket list: I’d now felt a jerk on my chain for a fiftyish cowboyish fellow. Go figure.

That didn’t mean I wanted to flirt. I was terrified, and showed it. He said, “I’m Charles Heist,” and moved farther into the light, but didn’t stick out his hand. My eyes adjusted enough to tabulate the array of stuff along the walls. On the left, a narrow iron-frame bed, with heaped-up blankets, and pillows lined the long way, against the wall. I hoped he wouldn’t suggest I consider it a couch. On the right, a battered black case for an acoustic guitar, a two-drawer filing cabinet, and a long blond wood armoire, one I couldn’t keep from noting would have been a pretty swank piece of Danish modern if it wasn’t ruined. But this was my brain pinballing to irrelevancies.

He helped me out. “You said on the phone you were looking for someone.” I’d called a number the day before and been called back—from the phone on the desk, perhaps.

“My friend’s daughter, yes.”

“Sit.” He pointed at a folding chair between the file cabinet and armoire. While I took it and scissored it open for myself, he watched, seeming frankly unashamed not to show any gallantry. I preferred the desk between us for now, and maybe he felt this, so that in fact the deeper gallantry was on view.

“Jane Toth sent you?”

“Yes.” Jane Toth was the social worker whose name the local police had given me after they’d finished shrugging off my expectation that they’d be any help in my search for Arabella Swados, whose trail had led to Upland. Eighteen-year-old Reed College dropouts three months missing didn’t meet their standard for expanding their caseload. So I’d gone to find Ms. Toth, a local specialist in destitutes and runaways. After subjecting me to a sequence of expectation-lowering gestures herself, she’d jotted Heist’s name and number on the back of her card and mentioned his weird nickname. She’d also warned me that his methods were a little unorthodox, but he sometimes produced miraculous results for families with trails grown cold, like Arabella’s.

“You bring some materials?”

“Sorry.” I would try to stop saying that. I dug in my purse for Arabella’s passport, with a photo taken just a year before, when she was seventeen. “I guess this means we don’t have to look in Mexico.”

“We’re not that near to Mexico here, Ms. Siegler. But if you wanted, there are places you could cross the line with a driver’s license.”

“I don’t think she has one.”

“Is she using credit cards?”

“She had one of her mom’s, but she’s not using it. We tried that.”

“Or you wouldn’t be here.”

The passport I’d slid onto his desk was clean and tight, and the tension in the binding snapped it shut, not that he noticed. Heist—I should call him Charles, only he wasn’t that to me, not yet—didn’t look at the passport. He stared at me. I’ve endured my share of male strip-you-bare eyework, but this was more existentially blunt, souls meeting in a sunstruck clearing. For an instant he seemed as shook that I’d entered his office as I was.

“I guess you don’t work along those lines so much, tracing documents and so on.” Duh. I was blithering.

“Not at all.”

“In high school she worked on an organic farm in Vermont.” Saying this, I found myself flashing on the mountains, the blasted expanses I’d just ducked in from. The blue. Arabella and I, we were an awfully long way from Vermont’s village green rendition of the rural now. “She got onto a kind of off-the-grid idea there, I think. You know, from similarly privileged kids who didn’t know any better than she did.”

“Off-the-grid isn’t always a terrible idea.” He said this without venting any disapproval my way, as much as I’d invited it.

“No, sure, I didn’t mean that. So, that is the kind of thing you do?”

“Yes.” Now the blue light of his stare was the same as that sky: killing me. Perhaps in mercy, he broke the tension, opened a desk drawer at his right. Of course a gun could come out. Or maybe this was the part of the script where he produced a bottle and two shot glasses. Perhaps I closely resembled the woman who had broken his heart. I leaned a little forward. The drawer was deep, and scraped free of the desk heavily. He scooped his hand down low and brought out a furry gray-striped football with a cone-like white snout and soft pink claws like the hands of a child’s doll. I surprised myself knowing its right name without even trying—an opossum.

The creature’s legs and thick bare tail dangled on either side of Heist’s arm, but it wasn’t dead. Its black eyes glistened. I sat back a little. The room had a warm woody smell, like underbrush, and now I credited it to the animal I hadn’t known was hiding in the drawer. Heist stroked the creature with one blunt finger, from between its catlike ears, down its spine, seeming to hypnotize it. Or maybe it was me that was hypnotized.

“Does it work like a bloodhound?” I joked. “I forgot to bring a scrap of clothing.”

“Her name is Jean.” He spoke evenly, still unaffronted by my flip tone. “She’s recovering from a urinary tract infection, if it doesn’t kill her.”

“Just a pet, then.”

“Some people thought so, but they were misinformed. I took her off their hands.”

“Ah. So now she lives in your desk?”

“For the time being.”

“Then what—you release her to the wild?”

“If she lives. She probably won’t.”

It all sounded a little righteous to me, but I didn’t have the zoological grounds to quibble. Still, I couldn’t keep from the impression that Heist cuddled the animal not for its own sake, and not even to impress me, but to salve his own desolation. Maybe just hearing about lost girls was too much for this person. I’d begun kicking myself for imagining he could locate one.

“What do you need to go forward?” I asked. “I mean, concerning Arabella.”

“I’ll ask around.” He stroked the opossum, who blinked at me.

“Should I pay you?”

“Let’s see what I find, then we’ll talk. Are there other names?”

“Other names?”

“Other names she might go under. Or names she’s thrown around, part of this time in her life. Friends, boyfriends, enemies.”

“I think she quit throwing names around. Quit calling home entirely. But I’ll check with her mom.”

“Anything is better than nothing.”

“There is one name, though I hesitate.”

He and Jean waited, all eyes on me.

“Leonard Cohen.”

“Go on.”

“She was a bit of a freak about him, I think that might be worth mentioning. Even before he died, I mean. It could be that’s the point of this, ah, general destination.” Not to add that I couldn’t think of one other fucking reason in the universe a thinking, feeling teenage vegan would migrate to this locale, but I didn’t want to insult the precinct Charles Heist and his little friend called home.

“You think she went up the mountain.”

“I couldn’t dismiss the coincidence.” Here was exactly as far as my sleuthing had gotten: Mount Baldy, one of those mountains Upland lay at the foot of, was home to Leonard Cohen’s Buddhist guru, had been for a decade or so his place of retreat. I couldn’t pick it out of the lineup of white-topped peaks, but for that I had the rental’s GPS, or maybe now this guy.

The prospect seemed to trouble him, and he waited a long time before producing his totally unsatisfying reply. “Okay. I’ll put it on my list.”

I wished he’d actually exhibit a list, even if it were scrawled on a Post-it, but it was at least good to hear him invoke the word. Action items, procedures, protocols, anything but this human freak show in a red leather jacket soothing or being soothed by his comfort opossum.

Well, wasn’t I the judgmental Acela-corridor elite? The bubble I’d fled, coming west, I actually carted around on my back like a snail’s shell, a bubble fit for one. As my fear abated, in its place a kind of rage coursed through me, that I’d come to this absurd passage, that I’d placed Arabella in hands such as these. Or that Arabella had placed me in them; it could be seen either way. Seeming to read me again, Heist lifted his free hand from Jean’s ears long enough to palm the passport into an interior pocket of the jacket. Too late for me to take it back. I was an idiot for not making a photocopy and for letting him near the original.

“Where can I find you?” he asked.

“I’m staying at the Doubletree, just down Foothill—”

“Under your own name?”

“Yes, but what I was going to say is could I come with you? Maybe I’d be able to help describe her—”

I’d stopped at a sound of clunking and rustling, directly behind me. I almost shit my pants. Another rescue animal? The front panel of the armoire slid open, and two filthy bare feet protruded sideways into the room, their ankles covered in gray leggings. The feet twisted to find the floor, and the rest of the person attached came writhing out, to crouch like the animal I’d mistaken her for.

A girl, maybe thirteen or fourteen, I guessed. Her black hair was lank to her shoulders and looked as though it had been cut with the nail clippers no one had taught her to use on her raw-bitten fingers. She wrapped her elbows around her knees and watched me sidelong, not turning her almond-shaped head completely in my direction. She wore a tubelike black sundress over the leggings. Her bare arms were deeply tanned, and lightly furred with sun-bleached hair contrasting with the black sprigs at both armpits.

“It’s okay,” said Heist. He talked past me, to the girl. “She isn’t looking for you.”

She sat that way, quivering slightly, pursing one corner of her mouth.

“She thought you might be an emissary of the courts,” he explained. It was nice he felt compelled to account to me at all, I suppose. I’d half risen from my chair. I sat again.

“Go ahead,” said Heist.

The girl scurried up and into the mound of blankets on the low bed. She took the same position beneath them, huddled around her knees, her eyes poking from the top as if from an anthill.

Was it a message to me, that I should remember some lost don’t wish to be found?

Heist lowered Jean gently back into her drawer and slid it shut. “This is Phoebe,” he said to the girl. “She’s looking for someone else, someone who ran away. We’re going to help her.”

We? I might cry now. Did the girl ride on Jean when they searched together? No, she’d need a bigger animal, a wolf or goat. Or maybe the detective carried her under his free arm, the one that wasn’t holding the opossum.

“I’ll find you at the Doubletree,” he said to me now. It wasn’t curt or rude, but I was being dismissed. I felt as though a trap door had opened under the chair.

“You sure I can’t go along?” I heard myself nearly pleading. “I’d like to get the lay of the land, actually. I’m only here for one reason.”

“Maybe after I make a few inquiries.”

“Great,” I said, then added lamely, “I’ll work things from my end in the meantime.” The words we exchanged seemed credible enough, if they’d been spoken in a credible atmosphere. Here, they seemed a tinny rehearsal, something having no bearing on what was actually being enacted in this room, a thing I couldn’t have named and in which I was an unwilling player.

Could I ask him for the passport back? I didn’t. The girl watched me as I went for the door, opened it to the blinding glare. For the first time, I noticed the water dish and food bowl in the corner—Jean’s meal station. Or maybe the furry girl’s. It occurred to me that Heist had introduced the opossum by name, but not the girl. I felt demented with despair, having come here. My radical gesture, to quit my privileged cage and go intrepid. Take the role of rescuer. Yet it was as though I’d been willingly reduced, exposed as nothing more than that opossum, or the girl in the blanket. My mission had defaulted to another surrender to male authority, the same wheezy script that ran the whole world I’d fled. All the lost girls, waiting for their detectives. Me, I’d be waiting at the Doubletree, to contemplate all the comforts I’d forsaken. And yet I felt also the utter inadequacy of the authority to whom I’d defaulted, he with not even a gun or a bottle of Scotch or a broken heart in his drawer, only a marsupial with a urinary tract infection. I was confused, to say the least. I got out of there.

4

BLAME THE ELECTION. I’D BEEN WORKING FOR THE GREAT GRAY NEWS organization, in a hard-won, lowly position meant to guarantee me a life spent rising securely through the ranks. This was the way it was supposed to go, before I’d bugged out. I’d done everything right, like a certain first female nominee we’d all relied upon, even my male friends who hated her, as a cap on the barking madness of the world. Now she took walks in the hills around Chappaqua, and I’d checked into the Doubletree a mile west of Upland, California.

I’d grown up a pure product of Manhattan, secretly middle-class in Yorkville. My parents were both shrinks, and their marriage was a device for the caretaking of my mother’s jittery, wrecked romanticism. An only child, I might have been one too many. I spent a lot of my childhood farming myself out to the houses of families with siblings, houses with a raucous atmosphere in which I could be semi-mistaken for just one more. It wasn’t so much that my parents discouraged my bringing friends home. When I did, my parents were always delighted, and, putting out tea and cookies, sat us down for what I imagined—still imagine—couples therapy might be like.

I saved my parents a calamitous sum by getting into Hunter College High School, then forced them to produce the calamitous sum by getting into college in Boston. The summer before my junior year I interned at a literary magazine, and when I returned to New York after graduation I worked there. It was a place that encouraged the nonsurrender of certain radical feminist-theoretical attitudes I’d cultivated at college, even as I prospered in an atmosphere of lightly ironized harassing “mentorship” in an office full of men ten years older than myself. From there to NPR, where I did research, prepping the one-sheets that made interviewers sound like they’d read books they hadn’t read. And then Op Ed, my foot in the door of the citadel.

The notorious day in November when my boss and all the rest of them sat deferentially with the Beast-Elect at a long table behind closed doors, to soak in his castigation and flattery, I conceived my quitting. At the start of the following week, I actually opened my yawp and did it, made a perverse stand on principle, stunning myself and those in range of hearing. The hate in my heart was amazing. I blamed my city for producing and being unable to defeat the monster in the tower. I already had my escape charted out, and I gave exactly zero of my accumulated mentors, or my parents, any say in the matter. For my thirty-three-year-old tantrum, I was patronizingly dubbed The Girl Who Quit. I think I won Facebook that day, for what it’s worth. I mean, of course, inside the so-called bubble.

Roslyn Swados had been my supervisor at NPR. Twenty years older than me, a public radio lifer, she was recently divorced when our friendship began. I was fresh off a juvenile breakup myself. She had me to her perfect Cobble Hill duplex for a dinner consisting of a bottle of white wine and a baguette and a giant hunk of Humboldt Fog, a cheese I’d somehow never tasted until that night. We polished them all off in an orgy of commiseration, then moved on to a bar of Toblerone.

Roslyn’s life ran along the lines of the New York I’d idealized growing up, one increasingly unavailable to those of us coming along after—the one implicit in a thousand short stories from the ’80s and ’90s issues of the New Yorker still stacked in my parents’ bathroom, some of which I’d memorized. It was only likely that her address was Cheever Place, a landmarked, tree-lined block that formed my sanctuary and ideal.

Neither of us were lesbians, so I couldn’t be in love with Roslyn. It didn’t make sense for me to want to be her, since there was no one for me to divorce yet. I wasn’t Roslyn’s daughter, either, since I still had a mother, and she had Arabella, who was a high school sophomore when I entered their lives, still living at home, though she had in some ways already grown elusive to Roslyn. It was more like I’d farmed myself out again, as I’d done before college. In this case, to a family where I could be a younger sister to the mother and an elder to the daughter. I’m sure Roslyn hoped I’d glue the two of them together at least a while longer. I never blamed her for making this calculation. Our friendship was real, and the calculation was wrong, as it happened. I couldn’t glue mother and daughter together, not even briefly.

But I did get close to Arabella. She trusted me. Soon I enjoyed two uncanny familial friendships, upstairs and downstairs in the same duplex. This was a kid who’d become a vegetarian at twelve, after reading Jonathan Safran Foer’s book, and who had three posters in her room: Sleater-Kinney, Pussy Riot, and Leonard Cohen. Her sexuality was unclear, but I got the feeling the sexuality of the entire high school at Saint Ann’s was unclear, so she had company. She no longer spoke to her father. She played guitar, badly. I worried when she told me Cohen’s “Chelsea Hotel #2” was her favorite song (giving me head on the unmade bed), but took heart when it became apparent she identified not with the female subject but with the male singer.

Arabella and her friends were those who couldn’t recall a time before 9/11, or only barely, an evil channel glimpsed before their parents dug the remote from the cushions to switch it off. Though they made me feel old, I rooted for her and her compatriots with the dumb devotion others reserved for sports teams. I frankly envied Arabella when she declared her disinterest in eastern colleges and applied to Reed. I thought she’d thrive there.

One night in September, I went to dinner with Roslyn. We met at Prune, on First Street. We sat on either side of a stew of mussels and leeks, our favorite, only nothing was right that night, and it was more than the nothing-is-right of foreshadowed electoral doom. Arabella hadn’t been calling home. Her texts were minimal, their tone hostile and defensive. Roslyn didn’t know what to do.

“Did you call your mother from college?” Roslyn asked bluntly.

“My mother wasn’t one you called,” I began. I said it with a glibness I regretted immediately.

“Arabella thinks of me the same way.”

Of course. Something obscure came clear, the reason I’d inserted myself so deeply in this family. I’d been free to behold and adore a mother and a daughter equally, even if they couldn’t themselves. In the system of my own family, I could only choose one side.

“I’ll reach out,” I said. The thing I knew she hoped I’d say.

I got Arabella on the phone, once. She didn’t like her classes, or Portland. She repeated a promise from before, that she would drop out and head down to Mount Baldy, to find Leonard Cohen. I treated this with skeptical amusement—a big mistake. And Arabella probably sniffed me out; she was too smart to fool. For the first time ever, I’d agreed to act as a go-between or mole for her mother.

Then came the week in November when, accompanying the national calamity, Leonard Cohen dropped dead. When Roslyn rang Arabella’s cell, she got only a text in return: I’m fine. Somehow, I thought, I’m fine never means what it says.

I urged Roslyn to contact the dean of students. She’d already been contenting herself, it seemed to me, with too little word from her daughter. Arabella was a New York kid, I reminded her. It meant she was equipped, sure, but also that the rest of the country, even funky Portland, would be an alien wonderland to her—never more than after November 8.

But Roslyn was a New Yorker too. Distracted, stoical, and now, like all of us, a little or a lot wrecked. She’d been hitting the white wine hard, without enough Humboldt Fog and baguette to soften the impact. I didn’t blame her. She satisfied herself with a few more flat-affect texts from Arabella until the day in mid-December when even those quit coming, and when calls to Arabella’s number resulted in a “Mailbox full” message.

Roslyn woke from her trance and bought a plane ticket to Portland. She was distraught enough that I offered to join her. We flew out on a Friday night, and we were together when Reed’s security let us into Arabella's dorm room, the single she’d fought for. The mess there included unopened mail dated as far back as September, masses of untouched schoolwork, and her abandoned passport, the one I’d now handed over to Heist. Like most New York eighteen-year-olds, Arabella wasn’t a driver, so she’d fled without an ID, which set off alarms. We talked with the dean of students on Monday before flying back east, but Arabella hadn’t made herself visible to their system of counselors and advisors. She’d been discreetly failing out from the start, and no one knew her.

Back in New York, I tried to help a nearly insensate Roslyn with some rote sleuthing. A credit-card record put Arabella on an Amtrak to Union Station in Los Angeles. Leonard Cohen, it didn’t take much to learn, had been recently living not on Mount Baldy, but in Los Angeles proper, among the Jews and pop stars, as would anyone with a brain. Well, not Arabella. The last thing the credit card’s trail revealed was a purchase—a bunch of groceries—from a supermarket called Stater Bros. in the Mountain Plaza Shopping Mall in Upland, California, fifty miles from the Pacific Ocean. It pointed to a pilgrimage to the Zen mountaintop, just like she’d promised. So, having sworn to Roslyn I’d find her daughter, I arrived in Upland for a look around.

Harvard, Hillary, Trump, the New York Times. Names I hated to say, as if they pinned me to a life that had curdled in its premises. Those might be summarized as feeling superior to what I hated, like the Reactionary White Voter, or the men who’d refused me the chance to refuse to marry them by refusing to ask.

Well, unlike the helicopter-raised people around me, I could look in a mirror without someone else holding it—or so I liked to think. If there was an outside to my fate, I’d locate it, or be damned inside the self-referential system of familiarities. Maybe I could bring back Arabella, and with her, a report from the exterior.

5

MY HOTEL WAS ONLY A MILE FROM THE DUSTY YELLOW MYSTERIES OF Upland, but it might have been a million. Claremont was a town that presented itself as an implacable fortress of non-native shade trees and well-kept craftsman houses, fitted around a college campus as empty and perfect as a stage set. In this cheery simulacrum I discovered nothing I could get a purchase on, apart from a lively record store, but I didn’t have any way of playing a record. So I took my phone to a bakery and coffee shop called Some Crust and read Elena Ferrante at an outdoor table and hoped for some amusing college student to hit on me. I got hit on by amusing senior citizens instead. Perhaps they, like the Klan, had been lately emboldened. I retreated to my hotel.

My room reminded me of a gun moll’s wisecrack, in some old film I’d seen, on entering an apartment: “Early Nothing.” I was left with Facebook, where my friends had responded to the election by reducing themselves to shrill squabbling cartoons. Or I could opt for CNN, where various so-called surrogates enacted their shrill hectoring cartoons without needing to be reduced, since it was their life’s only accomplishment to have been preformatted for this brave new world. Television had elected itself, I figured. It could watch itself too, for all I cared. I read my book.

On the second day without a call from Heist, it began to rain. There was dramatic promise in the storm’s beginnings, with a three A.M. lightning strike that might have been right over the Doubletree. It shook my room with a sound like a sonic boom just an instant after the flashbulb flare that had woken me. Could the world be saying no thanks to 2017, to the latest outlandish shithead cabinet appointment, after all? Maybe I’d come to California to join it in sliding into the sea.

But the lightning was mere overture to a dull steady rain that fell unceasingly through the day and night that followed, unimpressive except if I stepped outside the door of my room. The hard-baked desert ground, which exposed the lie of all those shade trees, didn’t soak the water up but refused it. The rain gathered in torrents coursing downhill, away from the mountaintops, which were no longer visible through the roof of gray mist. These gouts made every sidewalk crossing a whitewater rafting opportunity, only I didn’t have a raft. Southern California wasn’t made for pedestrians, needless to say, but today it wanted amphibious vehicles.

I retreated to my room to write e-mails, except the one that mattered, the one I owed Roslyn. I knew my friend was in tatters, waiting for me to deliver a miracle. Instead, I’d reduced myself to her West Coast equal, for the moment: a woman in a room, alone. I might be nearer to Arabella; likely I was. But I couldn’t prove it.

So my thoughts turned to my appointed savior. I Googled a few combinations of feral, detective, and Heist, but, surprise surprise, he didn’t have a website or Wikipedia page. Nor did it help that his last name doubled as an improper noun. Most of the results not involving crime movies were links to heartbreaking and lurid newspaper accounts of children abused by their caretakers in Florida and elsewhere, which pushed me off the search in disgust. I played some Leonard Cohen on YouTube through my computer’s lousy speakers. A fairly weak gesture in Arabella’s direction, but maybe it would somehow summon her up.

The third morning, I couldn’t take it anymore, and I tried Heist’s phone. I got his voicemail. “I can’t answer the phone. Please leave a message.” I called twice but left no message. Unlike the first time I’d heard it, I now had a face to go with that strange calm, flat tone: a strange calm, flat leathery face, bordered in extraordinary hairs. I couldn’t purge it from my thoughts, nor could I quit picturing his office. Was the furry girl wrapped in her blanket on that cot, jumping at the ringing of the phone? Or was he? Whose bed was that, anyhow? Were the girl and the opossum lapping together from the water bowl in the corner? I felt I might be obligated to bust in there and free that child, but I was paralyzed with uncertainty, and the absurd hope that Charles Heist was suddenly about to deliver Arabella and make sense of my dereliction of my own life, my own trajectory. I longed for my cubicle, for another Tinder date at the Bourgeois Pig.

I sent out a Hail Mary e-mail to my only actual Los Angeles acquaintance, a high school friend who’d Liked my quitting on Facebook and invited me to get in touch. Now, hearing my location, she broke the news that Culver City, where she worked in a gallery, was a nearly two-hour drive on a weekday, even without the rain. Still, I had nowhere else to be, unless I set out up the mountain to poke around the Zen Center on my own—the location was plain enough on Google Maps. But no, I’d give Heist at least one more day. So I told her I’d treat her to dinner at the best restaurant she could show me in Culver City. I needed the hell out of the Doubletree and the whole Inland Empire.

6

THE GPS INSTRUCTED ME TO “MERGE ONTO INTERSTATE TEN WEST, TOWARD LOS Angeles,” but in the robot’s voice it sounded like lost and jealous. The sea change from the suburban desert interior, of which there’d been stunning miles to traverse before I’d seen downtown passing on the right, was unaccountable. As the miles peeled beneath the tires I thought of Arabella, the western distances she’d had to go to make her disappearance—how many, exactly, I had yet to know.

Last I’d seen Arabella in person she’d been musing on what I then thought was her little joke, about finding Leonard Cohen. “Don’t you go hitchhiking now,” I’d said to her. “It isn’t 1972 anymore, except in your heart.”

“Don’t worry, I won’t,” she’d said, with a teenager’s glum exasperation. I hadn’t forced her to promise. Now, each mile ticked in me, a metronome of self-reproach. If I could have Arabella back now, I’d have tried to insert a tracking microchip under the skin at the nape of her neck, like they do with cats and dogs at the adoption shelter.

7

I MAY HAVE BEEN TO BLAME, BUT BY THE TIME OF OUR MEAL’S SECOND course, I figured I’d never call Stephanie again and might even block her if I didn’t have the brass to unfriend. Of course that’s when the conversation got interesting, at least a little.

“Everyone’s trying to get out of New York,” she informed me, in what I suppose she intended as a kind of congratulation. “You’re not even ahead of the curve. Out here it’s like, what took you so long?”