Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

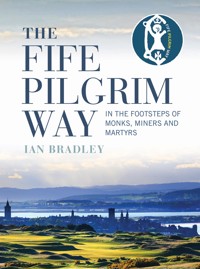

This book is the essential companion for anyone exploring the new Fife Pilgrim Way, whether on foot, by car or bicycle or simply as an armchair traveller. Packed with history, vivid anecdote and nearly 100 colour illustrations, it brings to life the fascinating communities and the characters along the route in whose footsteps modern pilgrims are treading. Setting off with Celtic saints and St Margaret from Culross and North Queensferry, marching with miners through the West Fife coalfields, carrying on with Covenanters and Communists, and ending among the martyrs, relics and ghosts of the haunted city of St Andrews, this gripping narrative presents a journey through Scottish history, ancient and modern, with spiritual reflections along the way.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 364

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Ian Bradley is Emeritus Professor of Cultural and Spiritual History at the University of St Andrews. He is a Trustee of the Scottish Pilgrim Routes Forum and has been closely involved with the Fife Pilgrim Way since its conception. Among his many other books are Pilgrimage: A Cultural and Spiritual Journey (2009), Argyll: The Making of a Spiritual Landscape (St Andrew Press, 2015) and Following the Celtic Way (Darton, Longman & Todd, 2018).

First published in 2019 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Ian Bradley 2019

ISBN 978 178885 194 7

The right of Ian Bradley to beidentified as Author of this work hasbeen asserted by him inaccordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part ofthis publication may bereproduced in any form or byany means without permissionfrom the publisher.

British Library Cataloguingin Publication DataA catalogue record for this bookis available from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by

Mark Blackadder

Printed and bound by PNB, Latvia

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

PART 1

Setting out with three saints: from Culross and North Queensferry to Dunfermline

1 Setting out from Culross with Serf and Kentigern

2 Setting out from North Queensferry with Margaret

3 Inverkeithing: a staging post and changing place

4 Dunfermline

5 Fife’s medieval religious communities

PART 2

Carrying on past coal mines, churches and conventicles: from Dunfermline to St Andrews

6 Marching with the miners

7 Ancient and Modern: from Kelty to Kennoway via Glenrothes

8 Bloody deeds along the way: from Kennoway to St Andrews

PART 3

Reaching the destination: St Andrews, the haunted city of relics and reformers

9 St Andrews: the pilgrim city

10 St Andrews: the Reformation city

11 Under the archways and through the gates of the haunted town

Conclusion: the end and the beginning

Select bibliography

Useful Information

Index of People and Places

Acknowledgements

I have benefited considerably from the friendship and encouragement of fellow founder members and trustees of the Scottish Pilgrim Routes Forum, especially the indefatigable and inspirational Nick Cooke, John Henderson, Roger Pickering, David Atkinson and Sheila Kesting. Fellow members of the ACTS Fife Pilgrim Way Steering Group have also been very supportive, notably Douglas Galbraith and Alan Kimmett. Ed Heather-Hayes and Miranda Lorraine from Fife Coast and Countryside Trust have been consistently helpful and encouraging. Tom Turpie generously allowed me to use and quote from the background notes which he produced for the Fife Pilgrim Way, Sheila Pitcairn shared with me her interesting and important work on Dunfermline as a place of pilgrimage and Giles Dove has let me quote from his fascinating St Andrews MPhil dissertation on ‘Saints, Dedications and Cults in Medieval Fife’.

In St Andrews, Bess Rhodes has been very helpful in sharing her knowledge of the Reformation and her infectious enthusiasm for the history of the cathedral. It was a joy to supervise Dawn Laing on a dissertation on the Fife Pilgrim Way. Clergy, worship leaders and church guardians along the route have opened their churches to me and helped me with queries, notably Jim Campbell at Ceres Parish Church, Alasdair Coles at All Saints’ Episcopal Church, St Andrews, Alan Kimmett at St Columba’s Church, Glenrothes, Colin Alston at St Peter’s Church, Inverkeithing, Fr Chris Heenan at St Margaret Memorial Church, Dunfermline, Fraser Munro at the Arnot Gospel Hall, Kennoway, Gordon Mitchell, Session Clerk of Kinglassie Parish Church, Leslie Barr in Kelty, Ian Brown and George Seath from Ballingry and Rosemary Wallace and Robert Martin from Auchterderran.

I learned much on a wonderful walk from Glenrothes to Markinch led by Bruce Manson, who has also helped me with historical queries about Markinch. A talk in St Andrews on pilgrim badges by Gavin Grant, Collections Team Leader with Fife Cultural Trust, and a lecture on the architecture of St Andrews Cathedral by Julian Luxford of the History of Art School at St Andrews University were also very helpful. David Thomson arranged a very useful meeting with members of Kinglassie Pilgrim Way and Heritage Group and Sandy Russell kindly let me borrow his rich collection of material on West Fife’s mining heritage. Catherine Stihler first alerted me to the importance, and the neglect, of the Battle of Inverkeithing. Paula Martin shared her knowledge of the history of Ceres with me, while Dave Reid put me right about where Archbishop Sharp may have spent his last night in Kennoway and Bill Hyland enlightened me about the life of the Augustinian canons. George Corbett, with whom I shared a walk on the Kennoway to Ceres stretch of the Pilgrim Way, shared his interesting theory about the origin of the name Ceres and offered other interesting information on the area.

Andrew Simmons and the whole team at Birlinn have been very supportive and helpful. I am grateful to Michael Brown and Katie Stevenson for permission to reproduce the extract from Medieval St Andrews (Boydell Press, 2017) quoted in chapter 10, and to Rosemary Wallace and Robert Martin for allowing me to quote the paragraph from Auchterderran Kirk (2016) reproduced in chapter 7.

Generous subventions from the Fife Coast and Countryside Trust and the Strathmartine Trust have contributed towards the provision of colour illustrations throughout this book, and their financial support is gratefully acknowledged. The map reproduced on pp. 10–11 was drawn by Jenny Proudfoot.

All photographic illustrations in this book are by the author except for those listed below, which are reproduced by kind permission of the copyright holders: pp. 2–3 John Murray; p. 12 Fife Coast and Countryside Trust; p.29 lower: Fife Cultural Trust; pp. 30–1 DGB/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 35 Kraft-stoff/Shutterstock; pp. 56–7 Carnegie Dunfermline Trust; p. 79 Historic Environment Scotland; p. 168 upper: John Murray; pp. 194–5 Mary McLeron/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 225 University of St Andrews; p. 251 upper: alanf/Shutterstock; p. 251 lower: MSP Travel Images/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 253 upper: John Stewart; p. 257 S.K. Reid Photography; pp. 266–7 Sarah Kennedy, Smart History, University of St Andrews; p. 270 Mike Wragg.

Introduction

Fife was long known as the pilgrim kingdom. This is because within its bounds were found the two most important places of pilgrimage in medieval Scotland, Dunfermline (which was also the residence of successive Scottish monarchs – hence the kingdom designation) and St Andrews. At the height of the pilgrimage boom in the Middle Ages, thousands of people from many parts of the British Isles and beyond traversed Fife to venerate the shrines of St Margaret and St Andrew. In the words of the medieval historian Tom Turpie, ‘The economy, communication networks, landscape and religious and cultural life of Fife, perhaps more than any other region of medieval Scotland, was shaped by the presence of pilgrims and the veneration of saints’ (Turpie 2016: 4).

Path to Kinglassie Well

The Fife Pilgrim Way, officially opened in July 2019, allows modern pilgrims to follow in the wake of their medieval predecessors and walk, cycle or otherwise make their way across Fife towards St Andrews on a route that has two starting points on the northern shores of the Firth of Forth: Culross, with its associations with two early Scottish saints, and North Queensferry, where Queen Margaret established the ferry crossing for pilgrims going to St Andrews. It is based on the premise that following in the footsteps of medieval pilgrims across Fife is a great way to discover the region’s remarkable past, its lively modern communities, countryside, historic towns and natural treasures. But it is much more than an exercise in historical reconstruction. For start, it does not follow the route taken by most medieval pilgrims who would have gone directly north from Kelty to Loch Leven and travelled on via Scotlandwell, taking a more northerly course. The modern pilgrim way has been deliberately routed through old mining and industrial areas of West Fife and the new town of Glenrothes. This is partly in the hope of bringing economic and other benefits to places which have experienced decline and do not see many visitors or tourists, as has happened in Galicia in Spain, the site of Europe’s most famous pilgrim way, the Camino de Santiago, which leads to the shrine of St James.

There is also a conscious desire that those journeying along the Fife Pilgrim Way will not only see pretty vistas and affluent villages, but also come into contact with places and people that have not been so favoured. King James VI of Scotland (later King James I of England) famously described Fife as ‘a beggar’s mantle fringed with gold’. The golden coastal fringe, with its quaint fishing villages and breathtaking views across the Forth, has long been the route of a hugely popular walk developed and maintained by Fife Coast and Countryside Trust. The Fife Pilgrim Way allows people to explore and encounter the beggar’s mantle, not so immediately and obviously appealing as the coast, but packed with historical, social and spiritual interest. It has been developed through a partnership between churches of all denominations, local history and heritage groups and others interested in the practice of pilgrimage brought together by the Scottish Pilgrim Routes Forum, which had its very first meeting in the old manse in Culross in 2012. Fife Council has been strongly supportive of the project from the beginning, and Fife Coast and Countryside Trust, an independent environmental charity spun off from the Council’s Rangers service, has been responsible for route-planning, way-marking, interpretation and marketing. It is appropriate that the first meeting of the Fife Pilgrim Way Network, bringing together interested parties from the churches, the local authority, voluntary organisations and others, took place on 11 July 2012 in Committee Room 1 of Fife Council’s headquarters at Fife House in Glenrothes.

The logo chosen for the Fife Pilgrim Way, which appears on the front cover of this book and on all signposts, maps, guides and promotional material, is based on a fifteenth-century lead alloy pilgrim badge discovered during excavations at St Andrews Castle in 1998 (see p. 29). It depicts the apostle Andrew, one of the first disciples called by Christ, being crucified on the diagonal cross on which he is said to have been bound rather than nailed in order to prolong his suffering. For the logo, a crown has been added at the top, to represent Fife’s royal connections and specifically the royal palace at Dunfermline, where many prominent Scottish kings and queens were born and laid to rest. Beneath the figure of the saint another image has been added in the form of the distinctive cross found carved into the inner wall of the tower in Markinch Parish Church, which stands roughly at the halfway point of the 64-mile long route and is one of the most interesting church buildings along it. The two round holes on the left-hand side of the badge are where it would have been sewn onto the hat or cloak of a pilgrim. On the other side, the frame or border is missing, as it is in the original badge, which is now on display alongside other pilgrim badges in the Kinburn House Museum in St Andrews. This gap conveniently allows the words ‘Fife Pilgrim Way’ to be inserted and form part of the design. It also points to the brokenness of pilgrims, many of whom set out on their travels to seek forgiveness for sins and come to terms with failings. All pilgrims are in some sense ‘the walking wounded’, carrying their hurts, guilt, unresolved tensions, unease and fears. The missing border of the pilgrim badge also points to the incompleteness of every earthly journey. We set out only to come back again, and every departure involves a return until we make the pilgrimage that awaits each and every one of us as we depart from this world.

The practice of pilgrimage, understood as a departure from daily life on a journey with a spiritual intention, and often – although not invariably – to a destination with a religious significance, is a central feature of all the world’s major faiths. It is not obligatory for Christians but it has long been a significant aspect of Christian life and devotion. Jesus sent out his disciples to preach the kingdom of God and to heal, telling them to go from house to house, taking nothing on their journey. Some early Christians, like the Celtic monks who wandered across continental Europe as well as around the remoter shores of the British Isles, took to almost perpetual pilgrimage as a demanding form of witness and exiled themselves from home comforts as they sought to follow the Son of Man who had nowhere to lay his head. The desire to walk in Jesus’ footsteps led other early Christians to journey to the Holy Land. As the cult of saints developed and certain places came to be seen as especially sacred, Christian pilgrimage reached its zenith in the Middle Ages, with thousands travelling for many months across Europe to Rome, Santiago, St Andrews, Dunfermline and other shrines associated with apostles, saints and martyrs.

Pilgrimage effectively ceased in Scotland with the Reformation. In fact, there is considerable evidence that St Andrews was in significant decline as a pilgrim destination fifty years or so before Protestantism was officially established in 1560. For the next 400 years and more pilgrimage and pilgrim places largely disappeared across Scotland as they did across the whole of Protestant Europe. The Reformers had good and understandable reasons for attacking the practice of pilgrimage, which had become associated with the buying and selling of indulgences and the idea of paying your way into heaven. The result was that pilgrimage became almost a dirty word in Scotland, at least in Presbyterian circles.

In the last three or four decades something remarkable has happened. There has been a widespread and striking revival of interest in the practice of pilgrimage across Europe. Somewhat surprisingly, perhaps, given its reputation for Presbyterian disapproval of the more Catholic practices of the Middle Ages, Scotland is in the van of this movement, with more new pilgrim routes being created here than in any other part of the United Kingdom. Significant initiatives across the country have been stimulated by a combination of local enthusiasm and support from the Scottish Government and local authorities keen to promote health, well-being and economic regeneration, as well as revived interest in local saints, and the Scottish Pilgrim Routes Forum’s efforts to bring together interested parties within churches, heritage groups and the tourism sector. Lingering Presbyterian unease has at last been put to rest, not least by a spectacular vote of confidence at the 2017 General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, which passed with acclamation a deliverance from its Church and Society Council affirming the place of pilgrimage within the life of the Church and encouraging congregations to explore opportunities for pilgrimage locally and the provision of practical and spiritual support for pilgrims passing through their parishes.

The Fife Pilgrim Way is one of six major walking and cycling pilgrimage routes currently being developed across Scotland by steering groups made up of local enthusiasts, churches, voluntary bodies and local authorities. Many of these volunteers represent member organisations of the Scottish Pilgrim Routes Forum, a national network set up in 2012 and a fully constituted Scottish charity which supports and facilitates the work of the steering groups and meets twice a year in locations closely associated with their work. The most ambitious of the new pilgrim ways will be a 185-mile coast-to-coast route linking Iona and St Andrews, two of Scotland’s most iconic religious sites and places of medieval pilgrimage. The second longest, initially created in 2013 by a group of enthusiasts from Paisley Abbey, is the 149-mile Whithorn Way from Glasgow to Whithorn, once the site of a major cathedral associated with St Ninian and an important place of pilgrimage since the seventh century. The 72-mile Forth to Farne Way, linking North Berwick to Lindisfarne, opened in 2017. In north-east Scotland, the 40-mile Deeside Way follows the route of the old railway track between Aberdeen and Ballater. The most northerly of the new pilgrimage routes is the St Magnus Way, a 55-mile walking trail across mainland Orkney from Evie to Kirkwall, opened in 2017 to mark the 900th anniversary of the martyrdom of Orkney’s patron saint. The development of these six routes represents the beginning of a long-term strategy co-ordinated by the Scottish Pilgrim Routes Forum to create opportunities for local people and overseas visitors alike to learn from and experience Scotland’s rich pilgrimage heritage through the outdoor environment.

Those who use the Fife Pilgrim Way, whether to make the whole 64-mile trek on foot or to travel along a short section by bicycle, wheelchair or other means of transport, will have many different motivations. For some it will be primarily to take some exercise, get some fresh air, enjoy the countryside or explore historic sites. Others may have, or come to have, more spiritual reasons for undertaking pilgrimage. Before beginning to explore the route in terms of its historical and spiritual significance, it is worth briefly examining the motives that have taken people on pilgrimage in the past and what the differences are between medieval and modern pilgrims.

If we are going to begin to enter into the medieval pilgrim’s mindset we need to appreciate the overwhelming fear of death, judgement, Hell and damnation that was universal throughout Europe in the Middle Ages. We can gain some sense of this from those terrifying images of the Last Judgement and the eternal torments of Hell found on so many wall paintings in medieval churches. Medieval Christians lived in perpetual fear of being condemned as a sinner at the Last Judgement and being cast into the fiery furnaces of everlasting damnation. The (almost literally) burning question for them was ‘What must I do to be saved?’ This was what inspired their attitude of penitence, understood as contrition, repentance and resolve to atone for their misdemeanours and obtain God’s forgiveness. It also underlay the complex system of penances established by the Church. These were prescribed penalties for sins which, taken together with earnest and sincere repentance and resolve to live better lives, were believed to mitigate the chances of facing damnation and secure the real possibility of salvation and entrance into heaven.

It is against this background of a prevailing attitude of penitence and the performance of numerous penances imposed by the Church that we need to understand medieval pilgrimage. Many pilgrims saw themselves first and foremost as penitents – they left home, often on long, uncomfortable, unpredictable and perilous journeys, in a spirit of penitence and in an effort to cleanse their souls and atone for their sins and failings – in some ways the more uncomfortable and hazardous the pilgrim journey, the better it was and the more likely to benefit those undertaking it in terms of a cleansing and purgative experience. Many pilgrims were also actually serving out penances prescribed by the Church or by the civil authorities. Medieval Scottish courts had the power to require those convicted of homicide to make a pilgrimage on foot to one of the shrines of the head saints of Scotland, of whom Andrew was the most prominent. The churches also regularly imposed a pilgrimage as a penance on someone who had confessed a sin to a priest or bishop. Several pilgrims came to St Andrews from continental Europe having been prescribed the journey there as a penance by local civil or ecclesiastical courts (see p. 213).

It was this penitential aspect of pilgrimage, and this overriding fear of death, judgement, Hell and damnation, that led to the development of the whole apparatus of indulgences which became so associated with late medieval pilgrimage and which so damned it in the eyes of the Protestant Reformers. The doctrine of Purgatory developed in the early Middle Ages to provide some kind of hope for those, the great majority of the population probably, who felt that they could never properly atone in this life for the sins that they had committed and feared that however penitential they were and however many penances they performed, they would still be found guilty at the terrible judgement seat and committed to perdition. Purgatory provided a second chance, a kind of halfway house between this world and the next, a post-mortem state of existence which allowed souls to be purified and refined and cleaned before facing the last judgement. It was envisaged in temporal terms and often seen as being a long haul. Indulgences, which came to be sold by the Church to raise money for building and other projects, allowed people to shorten their time in Purgatory, speed up the process of spring-cleaning their souls and get to the Day of Judgement more quickly and also in a more spick and span state. Undertaking a prescribed pilgrimage was one of the main ways of gaining an indulgence.

That is one reason why people went on pilgrimage. Another takes us to a second striking feature of the medieval mindset which is difficult for us to grasp today – its fascination and obsession with saints and relics. The cult of saints arose as the years and the centuries passed from the time of Jesus and the apostles, and a need seems to have been felt for more recent holy men and women as role models and objects of reverence and honour. Martyrdom played a key part in the creation of saints – those who had died for their faith became especially venerated. In many areas, not least Scotland, local saints were important. Along with the cult of saints came the cult of relics and corporeal remains. This stemmed from a very physical and literal approach to the faith, where people believed that by touching, or even seeing or being in close proximity to the bones, clothes or other objects associated with the saints, they would somehow pick up some of the spiritual power and aura of these superhuman and super-holy men and women. This idea was expressed in the widespread belief that in death the saints performed posthumous miracles, especially miracles of healing. The performance of miracles was, and still remains in the Roman Catholic Church today, a key determinant of sanctity – and it was the miracles that were widely reported as taking place at and around saints’ shrines which drew many people to them.

Saints’ shrines, especially, drew those seeking healing and relief from pain and suffering, whether physical, mental or spiritual, both for themselves and for others. Many medieval pilgrims fell into this category. People also made pilgrimages in the Middle Ages to give thanks for deliverance from pain, for the birth of children or for good harvests and other blessings and benefits. Quite often these pilgrimages of thanks were made in fulfilment of vows that the pilgrims had made earlier when they had prayed for deliverance.

So there were a number of spiritual motives which took people on pilgrimage in the Middle Ages – penitence, penance, accessing the power of the saints still latent in their physical remains and relics, seeking physical and psychological healing, giving thanks and generally benefiting the soul and bringing one closer to Heaven. But it is clear also that many pilgrims were motivated by rather less exalted and less spiritual impulses. They were more like modern tourists and holidaymakers. Pilgrimage provided just about the only opportunity available for most people in the Middle Ages to leave the confines of their home village, their family and the ties that bound them. It meant adventure, new sights, meeting new people and getting away from the abusive husband, the nagging wife or the meddling parish priest.

The motives that take people on pilgrimages today are as many and various as they were in the Middle Ages, and perhaps not quite as different as we might think. The quest for a deeper spirituality and for mental, physical and psychological healing is mixed with a sense of adventure, a desire to get out of the rut, broaden horizons and enjoy a new and different experience. Pilgrimages are still undertaken with a penitential purpose, as part of an attempt to reorientate lives away from selfishness and make a new start, to face challenges and experience, if only temporarily, a simpler and less comfortable lifestyle. Of course, there is nothing like the same fear of Hell and judgement today as there was in the Middle Ages. The decline of belief in Hell was one of the most significant theological trends in the nineteenth century, and it has continued apace since then. But that does not mean that people are not dissatisfied or uneasy about their lives and lifestyles – indeed, in some ways we are perhaps even less at ease with ourselves and more prone to angst and self-doubt than our medieval ancestors were. For not a few pilgrims today, especially those undertaking a long and rigorous walk like the Camino de Santiago, part of the motivation is a cleansing of the soul, although some might not put it in quite those terms, and a desire for a period and process of self-examination and reorientation, often coupled with a yearning for a simpler and less selfish lifestyle.

There is a strong sense of shared community about taking part in a pilgrimage which many people welcome in our increasingly atomised and individualistic culture. Pilgrims form egalitarian and inclusive communities in which individuals are temporarily freed of the hierarchical roles and status which they bear in everyday life. I vividly recall the first words of our leader when my wife and I joined a group of pilgrims walking the St Olav Way to Trondheim. As we were about to introduce ourselves, he said: ‘It is not important where we come from or what jobs we do. For the next week we are all simply pilgrims.’

Pilgrimage is often undertaken today to mark a significant birthday or anniversary, or an important landmark in life such as retirement. Part of the reason why the number of people making a pilgrimage is on the increase is undoubtedly because of the growing appeal of sabbaticals, gap years and taking time out from ever more stressed lives. There are also still those who are primarily motivated by a desire to give thanks or seek healing. The current revival of interest in the practice of pilgrimage ties in with the recovery of a sense of the sacredness of place and landscape in an increasingly fragile and urbanised world, and the growing emphasis on physical well-being and exercise. This is a further significant motive for many of today’s pilgrims, and it is why bodies like the Scottish Government and local authorities support the development of pilgrim ways as an aspect of their strategies to combat obesity, promote physical fitness and encourage exercise. Pilgrimage also ties in with the widespread desire today to rediscover and connect with roots, traditions and history, especially local history – which is why some of the most enthusiastic partners in the creation of Scottish pilgrim routes have been local history, heritage and conservation groups.

Many people find it easier to walk rather than talk their faith, and find encouragement through treading in the footsteps of countless pilgrims before them. Walking has clear psychological as well as physical benefits, as St Jerome discerned in the fourth century in his observation solvitur ambulando (it can be solved by walking). An experienced Christian therapist has shared with me how beneficial it can be for people to make confession, formal or otherwise, and get things off their chest while walking side by side with a companion/confessor rather than in a more confrontational face-to-face encounter. I have certainly experienced some of the deepest and most profound conversations of my life while walking alongside a fellow pilgrim, often someone whom I did not know and did not expect to meet again.

There are also numerous pilgrims today, as there were in the Middle Ages, who are impelled by a sense of adventure, or wanderlust, and who are perhaps as much tourists as pilgrims. But we need to be careful about making too hard and fast a distinction between these two categories. The dividing line between pilgrims and tourists has long been blurred, and is becoming more so. It has been said that while tourists return from their travels with souvenirs, pilgrims come back with blessings. Yet pilgrims have long picked up souvenirs, like the badges depicting Andrew and other saints that were mass-produced between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries to be sewn on to hats and cloaks, and many modern camera-toting and coach-borne visitors to churches and sacred places pause to light a candle and pray. If some of what passes for pilgrimage today is really tourism, it is also the case that many modern tourists are searching for something beyond a holiday. This provides a great opportunity for the Church today to help tourists become pilgrims.

Pilgrimage has much to offer an age such as ours where there is so much anxiety, stress, yearning and seeking. It fits the needs of a restless generation – but perhaps restlessness is, in fact, part of the human condition. Bruce Chatwin, the travel writer, has suggested in his book Songlines that humans are born to be nomads and that our natural inclinations turn us towards movement and journeying. The desire to be pilgrims reflects yearnings to find a deeper purpose and meaning in our lives. It also chimes with the way that increasing numbers of people see their faith. Surveys suggest that far more Christians now describe their faith as an ongoing journey rather than as a sudden decisive conversion experience. The road to Emmaus, along which the resurrected Jesus travelled with two of his disciples for many miles before they recognised him, seems to resonate with more believers nowadays than the road to Damascus, where Paul underwent a sudden blinding conversion.

The Latin word peregrinus, from which the word pilgrim is derived, means a stranger or traveller (literally per ager, or through the land). Pilgrimage is a provisional, transitory state, often taken as a metaphor for the journey of life, hastening irrevocably from the cradle to the grave. It is a reminder that all things in this world are temporary and that everything is in motion, nothing is ever static. In several religious traditions, pilgrimages to remote places are often undertaken towards the end of life to prepare for death by stripping away the comforts and distractions of this world. For some, pilgrimage is a perpetual state of life, as it was for the wandering Irish monks of the Dark Ages and is now for the Hindu sadhus who have renounced the world and perpetually travel from one shrine to another. For most of us, however, pilgrimage is an occasional rather than a perpetual state – one for which we prepare and from which we return in some small way changed, healed, refreshed and enriched, with our horizons broadened. In practical terms, it gives those of us who are not monks or free spirits, who are tied to the responsibilities and obligations that come with family or employment, the chance to leave our settled routines for a while, walk in the footsteps of the saints and the faithful of countless ages and find new companions on the way.

It has been said that one of the differences between tourists and pilgrims is that while the former pass through places, the latter allow places to pass through and affect them, with more engagement with those whom they meet on the way and in whose footsteps they are travelling. That is why this book has much about the customs, lives and beliefs of those people who have lived and worked and walked over the centuries along the route taken by the Fife Pilgrim Way today. Some pilgrim routes go through wild, spectacular remote scenery and have long stretches where there is little but raw nature and untamed wilderness. The Fife Pilgrim Way is not like that – you are never far from civilisation and the landscape is for the most part either urban, post-industrial or agricultural. Fife’s only significant relatively remote and mountain wilderness-like area, the Lomond Hills, is not on the route. This means that there are ample opportunities along the way to interact with people and communities, their stories, their roots, their faith and doubts. The old saying, ‘It taks a lang spoon tae sup wi’ a Fifer’, might be taken to suggest that the inhabitants of Fife are somewhat unfriendly and inhospitable. Behind the reserve and what can sometimes seem like dourness, there is, in fact, much genuine friendliness and kindness to be found among the native inhabitants of the pilgrim kingdom.

Pilgrimage can be undertaken alone, with one or two companions or in a larger organised group. It can be intentional, casual or random. More than other forms of travel, it involves a certain vulnerability in being open to others and to experiences that may be unsettling or disturbing as well as exhilarating and reassuring. In pilgrimage, the return journey is as important as the outward journey or the destination. The pilgrim comes back changed and hopefully more open as well as more faithful than before. The late eighteenth-century French writer Chateaubriand maintained that ‘there was never a pilgrim that did not come back to his own village with one less prejudice and one more idea’.

Ultimately pilgrimages, especially those involving physical exertion, are like life itself. The Fife Pilgrim Way has its dull stretches along boring and uninteresting roads, through grim surroundings and past ugly buildings as well as offering moments of beauty and elation walking through woods and beside streams or contemplating a sunset over distant hills. Every pilgrimage has its own rhythms and rituals, its ebb and flow of arriving and departing, exodus and return. The outer physical journey mirrors the inner spiritual journey.

Before concluding this introduction, I want to acknowledge and pay tribute to those who have developed and walked other pilgrim ways through Fife over recent decades. Several pioneered routes before the Fife Pilgrim Way was conceived and planned. Perhaps the first in the field was Cameron Black, who researched a route from Edinburgh to St Andrews, which he called the St Andrew’s Way, following more directly in the wake of medieval pilgrims via South and North Queensferry, Dunfermline, Keltybridge, Scotlandwell, Falkland, Kingskettle and Ceres. This was the route chosen in reverse for the Pilgrims Crossing Scotland 2000 project, part of the Europe-wide Christian celebrations to mark the dawn of the third millennium. Over four days in September 2000 a group of several hundred pilgrims walked from St Andrews to Edinburgh carrying a large oak cross. Their pilgrimage provided the western ‘arm’ of a huge cross which was traced by pilgrims walking across Europe, from Trondheim in Norway in the north, Thessaloniki in the south and Iaşi in Romania in the east. I was among those who set off on 10 September on the first leg to Ceres following a commissioning service in St Andrews Cathedral. The pilgrimage reached its destination, Holyrood Abbey, on 14 September, Holy Cross (or Holy Rood) Day, commemorating the occasion when King David, hunting in the forest below Arthur’s Seat, saved himself from attack by brandishing the cross-shaped antlers of a stag and subsequently vowed to set up an abbey on the site in thanksgiving for his deliverance. On St Andrew’s Day 2000 the cross which had been carried by the pilgrims was erected on Inchgarvie Island in the Forth, where it can still be clearly seen by those travelling across the Forth rail bridge.

There have been a number of recent Roman Catholic pilgrimages from North Queensferry to St Andrews. In 2011 Hugh Lockhart, a retired soldier, devised a route called The Way of St Andrews, and also known as St Margaret’s Way, which uses the Fife coastal path until just before Earlsferry (the destination of a medieval pilgrim sea crossing from North Berwick) and then strikes north through Kilconquhar, Colinsburgh and Largoward to St Andrews. In August 2016 members of the Confraternity of Ninian, which is dedicated to the reconversion of Scotland to Roman Catholicism through pilgrimage, walked in three days from the shrine of St Andrew in St Mary’s Roman Catholic Cathedral in Edinburgh via Dunfermline, Kelty, Scotlandwell, the Lomond hills, Falkland, Ladybank, Springfield, Cupar and Blebocraigs to St Andrews Cathedral, where they celebrated Mass in Latin as it would have been done before the Reformation. The ‘Two Shrines Pilgrimage’ as it is called has become an annual event. Those involved in a charismatic Roman Catholic group called ‘New Dawn’ make a much shorter pilgrimage through the streets of St Andrews every July and celebrate Mass (in English) in the cathedral ruins as part of their annual gathering in the town. There was a particularly memorable and moving celebration there on 5 July 2018, the 700th anniversary to the day of the cathedral’s consecration, not least because of the seemingly miraculous appearance of a saltire formed by cloud vapour in the otherwise blue sky at the moment of consecration. It remained floating above the east end throughout the distribution of the elements and faded away at the end of the Mass.

There have been other notable projects to promote pilgrimage in Fife. The St Andrews Cathedral Project was founded in 2000 on the initiative of David Dow, an architect based in north-east Fife, with the aim of resurrecting St Andrews Cathedral as a pilgrim destination and to promote pilgrimage to people of all faiths and none. It mounted several temporary exhibitions on the theme of medieval pilgrimage through Fife in churches and other venues in and around St Andrews under the title ‘Sair Hearts, Sair Feet, Sair Heads’. It also developed an interesting and fruitful inter-faith dimension by linking Christians with Muslims in Dundee. I was privileged to take part in a packed meeting in St Andrews in which both Muslims and Christians shared their own experience of pilgrimage.

Forth Pilgrim Ltd was set up as a Social Enterprise Company in 2007 by Roger and Eileen Pickering with the goal of establishing a 300-mile pilgrim way from St Andrews to Durham. They have grown interest by leading guided walks for groups to pilgrim places like Dunfermline and St Andrews. Through teaching the history of pilgrimage outdoors with school groups using drama, costume and fun, they engage young people in ‘history where it happened’.

Roger Pickering’s own enthusiasm was a major catalyst in the early development of the Fife Pilgrim Way and was instrumental in drawing various organisations and individuals who met round the table in 2012 into a lasting alliance.

Among several pilgrimage routes devised by Donald Smith of the Scottish Storytelling Centre in Edinburgh is the St Margaret Journey, which offers two routes from North Queensferry to St Andrews, one using the Fife coast path and the other broadly taking the same course as Cameron Black’s St Andrews Way. These routes were planned on the initiative of the Scottish Churches Trust and are promoted on the website ‘Scottish Pilgrim Journeys’, and in the Pilgrim Guide to Scotland (2015).

So, just as Jesus tells us that His Father’s house has many mansions, there are many different ways of traversing the pilgrim kingdom of Fife. This book will focus on the officially designated, established and waymarked Fife Pilgrim Way, which means that it will not cover the significant historical and spiritual sites at Loch Leven, Scotlandwell (which is, in fact, in Kinross and outside the kingdom of Fife) and Falkland which were on the medieval pilgrim route. It is not a guidebook. It does not aim to provide detailed descriptions of buildings and sites along the way, although many are mentioned, nor is it designed to help modern pilgrims navigate their way. Rather, it aims to set the Fife Pilgrim Way in its historical and spiritual context. It tells the stories of those who have walked this way before – among them monks, miners and martyrs – because a key part of pilgrimage is following in other people’s footsteps. It sketches in something of the traditions and history, especially the religious history, of the places and communities along the route. It also offers brief spiritual reflections and themes to ponder at the end of each section. You do not need to take it with you in your knapsack – it won’t tell you where you have taken a wrong turning or help you when you need to find the nearest toilet or bus stop. It is more for reading before you set out and perhaps again after you return – or even indeed to help armchair pilgrims to make the journey in their imaginations. There are many ways to be a pilgrim and not all of them involve putting on walking boots or cycle clips and braving the elements. I hope that this book will enhance the appreciation and deepen the experience of those who journey on the Fife Pilgrim Way in whatever way they choose or are able.

Fife Pilgrim Way logo

Medieval pilgrim badge

PART 1

Setting out with Three Saints:

From Culross and North Queensferry to Dunfermline

Dunfermline Abbey nave

1

Setting out from Culross with Serf and Kentigern

Although most medieval pilgrims began their journey to St Andrews from North Queensferry, and it may seem more logical for modern pilgrims to begin there as well, the alternative starting point of Culross offers two distinct advantages. First, as one of the most picturesque and perfectly preserved burgh towns in Scotland, it provides a more scenic and historical setting from which to begin the journey through Fife. Second, it allows pilgrims to set off in the company of two early Celtic saints, Serf and Kentigern.

Culross lies in the south-west corner of Fife. It only became part of the pilgrim kingdom in 1891, when it was transferred from Perthshire by the Boundary Commissioners. It reached the height of its prosperity in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries when George Bruce, who is commemorated by an imposing memorial in a family vault attached to the parish church, exploited the rich coal seams under the Forth and also developed a successful salt manufacturing business. Extensive trade with the Low Countries and Scandinavia made its harbour the fourth biggest in Scotland. The picturesque houses that line the cobbled streets rising steeply from the shore (and called either causeways or braes) date from this period. Another important industry was the manufacture of iron girdle pans for making pancakes and oatcakes. These industries have long since gone and the small town fell into considerable decline until the newly formed National Trust for Scotland set about restoring its ‘little houses’ in the 1930s. It now has something of a picture-postcard appearance, but pilgrims setting off from here cannot but be conscious of the industrial landscape nearby. Looking out across the Forth, the skyline is dominated by the tanks, pipes and chimneys of the huge Grangemouth oil refinery opposite, and to the west stands the gaunt outline of the Longannet Power Station, the last coal-fired power station in Scotland, which was closed in 2016. Grangemouth has not been without its problems, and with the phasing-out of fossil fuels there must be a question mark over its future. This industrial landscape proves a salutary reminder of the temporary and transitory nature of human endeavour and industry as pilgrims begin their journey.

Culross Abbey