Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

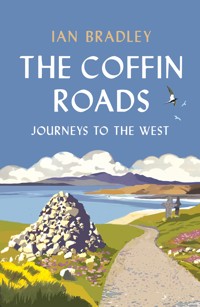

'Coffin roads' along which bodies were carried for burial are a marked feature of the landscape of the Scottish Highlands and islands – many are now popular walking and cycling routes. This book journeys along eight coffin roads to discover and explore the distinctive traditions, beliefs and practices around dying, death and mourning in the communities which created and used them. The result is a fascinating snapshot into place and culture. After more than a century when death was very much a taboo subject, this book argues that aspects of the distinctive West Highland and Hebridean way of death and approach to dying and mourning may have something helpful and important to offer to us today. Routes covered in this book are: The Kilmartin Valley – the archetypal coffin road in this ritual landscape of the dead. The Street of the Dead on Iona – perhaps the best known coffin road in Scotland. Kilearnadil Graveyard, Jura – a perfect example of a Hebridean graveyard. The coffin road through Morvern to Keil Church, Lochaline - among the best defined and most evocative coffin roads today. The Green Isle, Loch Shiel, Ardnamurchan - the oldest continuously used burial place anywhere in Europe. The coffin road on Eigg – with its distinctive 'piper's cairn' where the coffin of Donald MacQuarrie, the 'Great Piper of Eigg', was rested. The coffin road from Traigh Losgaintir to Loch Stocinis on Harris - popular with walkers and taken as the title for a best-selling thriller by Peter May. The coffin road on Barra – A detailed study of burial practices on Barra in the early 1950s provides a fascinating record of Hebridean attitudes to dying, death and mourning.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 277

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Ian Bradley is Emeritus Professor of Cultural and Spiritual History at the University of St Andrews. Among his many books are Pilgrimage: A Cultural and Spiritual Journey (2009), Argyll: The Making of a Spiritual Landscape (St Andrew Press, 2015), Following the Celtic Way (Darton, Longman & Todd, 2018) and The Fife Pilgrim Way (Birlinn, 2019).

The Coffin Roads: Journeys to the West is the second in a trilogy of books on aspects of death and the afterlife. The first, The Quiet Haven: An Anthology of Readings on Death and Heaven, was published in 2021 by Darton, Longman & Todd and the third, Breathers of an Ampler Air: Heaven and the Victorians, is due to be published by the Sacristy Press in 2024.

The Coffin Roads

Journeys to the West

Ian Bradley

First published in 2022 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Ian Bradley 2022

The right of Ian Bradley to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 779 0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Papers used by Birlinn are from well-managed forests and other responsible sources

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Map

Introduction

1 The Original Coffin Road: Kilmartin Valley

2 Towards the Shrine of a Saint: The Street of the Dead, Iona

3 Intimations of Heaven: Jura

4 Watching over the Churchyard: Morvern

5 Islands of Graves: The Green Isle, Loch Shiel

6 Death Croons and Soul Leadings: The Piper’s Cairn, Eigg

7 Premonitions and Apparitions: Kintail

8 Wakes and Whisky: Barra

9 Epilogue: Revisiting the Coffin Roads Today

Notes

Further Reading

Index

Acknowledgements

I have derived considerable benefit from conversations with Dr Lorn Macintyre, Alastair McIntosh, Iain Thornber, Lord Bruce Weir, Canon John Paul MacKinnon, Father William Fraser and Father Roddy Johnston. I am grateful to Iain Thomson for permission to quote from Isolation Shepherd, to Dr Mickey Vallee for permission to quote from the 1955 article by his grandfather, Professor Frank Vallee, on burial practices in Barra, and to John Bell and the Wild Goose Resource Group for permission to quote ‘The Last Journey’. Hugh Andrew and Andrew Simmons of Birlinn have been consistently supportive and helpful. Helen Bleck has been a meticulous copy editor.

This map shows only the coffin roads and graveyards featured in the numbered chapters and not those mentioned in the Introduction

Introduction

Walkers and cyclists exploring the Highlands and Islands of Scotland are very likely to find that coffin roads feature on their itineraries alongside drovers’ tracks and other traditional rights of way. Some of the most popular and well publicised walks in the west of Scotland carry this somewhat macabre designation. Perhaps the most frequented is the five-mile Stoneymollan coffin road from Balloch to Cardross, which forms part of both the John Muir Way and the Three Lochs Way, and links Loch Lomond with the Firth of Clyde.

Longer coffin roads are to be found rather further afield in the north-west Highlands. They include several challenging routes promoted on websites like ScotWays Heritage Paths and Walkhighlands, such as the nine-mile path from Kenmore to Applecross, the 26-mile Kintail coffin road from Glen Strathfarrar to the graveyard at Clachan Duich on the north shore of Loch Duich and the 28-mile Bunavullin coffin road which crosses Morvern from Bunavullin to Laudale House on Loch Sunart.

Another lengthy coffin road, which has been researched by the South Loch Ness Heritage Group, is thought to have extended for 25 miles from Whitebridge on the east side of Loch Ness to the burial ground at St Kenneth’s Church at the north end of Loch Laggan. It went over the Monadhliath hills and through Glen Markie, crossed the Spey at Crathie and then passed Loch Crunachdan before reaching its destination at Kinlochlaggan. Early Ordnance Survey maps show Cnocan nan Cisteachan to the west of Loch Crunachdan as ‘the Hillock of the Coffins’. Shorter walks along coffin roads include the one-and-a-half mile Bohenie coffin road, which goes through Glen Roy from Bohenie to Achluachrach in Lochaber, the two-mile track along the north side of Loch Moidart from Glenuig to Kinlochmoidart, and the two-and-a-half mile track which climbs through native birch-wood from near Abriachan on the northern side of Loch Ness.

There are also numerous coffin roads on the islands of the Outer and Inner Hebrides, the best-known perhaps being the four-mile track that crosses the south of Harris from Leacklea (sometimes spelled as Lacklee or Leac-a-li) near the head of Loch Stockinish in the Bays area on the east of the island to Tràigh Losgaintir on the west. Known as the Bealach Eòrabhat, it stood in for the desolate landscape of Jupiter in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, which included helicopter shots of the route. It also provides the title for Peter May’s best-selling ecothriller, Coffin Road, first published in 2016, which begins with the central protagonist being washed up ashore on Luskentyre beach (Tràigh Losgaintir) on the south-west coast of Harris. He has lost his memory and has no idea who he is or how he has come to be there. The only clue that he can find is a folded Ordnance Survey Explorer Map of South Harris, on which he has highlighted with a marker pen the route of the Bealach Eòrabhat. So it is on that coffin road that he begins the search for his lost identity. There are well-attested coffin roads on Mull and Barra.

As their name implies, these ancient and well-worn tracks were developed so that the bodies of the dead could be carried for burial to the remote graveyards that are still such a feature of the West Highland and Hebridean landscapes. They tended to be specially designated for this purpose, and to be distinct from routes along which the living would pass on their daily business, although several were later adopted as public tracks and roads. Journeys along the coffin roads were often lengthy and arduous, with relays of six or eight men carrying the coffin either on their shoulders or on long spokes. They would stop at frequent intervals for rest and refreshment and to be relieved by another bearer party. The slow progress on foot from place of death to place of burial could sometimes last for two or three days and nights and involve several hundred bearers and mourners walking through wild and desolate country with their food, drink and bedding carried by packhorses.

Along the routes of many of the coffin roads, cairns were erected, as illustrated on the front cover of this book. Some of them can still be seen today. They marked the places where the bearer parties stopped to rest. In some cases, the cairns may even have provided a platform on which the coffin was rested. Those carrying coffins would either build a small cairn to commemorate the dead at each resting place or add stones to an existing cairn along the route so that the ‘resting cairns’ gradually grew in size. Perhaps the most spectacular ones that can still be seen today are the four prominent cairns on Dun Scobull on the Ardmeanach peninsula on southeast Mull, which mark the place where the coffins of successive generations of the MacGillivray family were rested on their way to be buried at Kilfinchen churchyard. On his travels through the Highlands in 1927, Thomas Ratcliffe Barnett saw several heaps of coffins on the Glensherra road between Loch Crunachdan and Loch Laggan. I have not myself been able to verify if they are still visible today, but I have seen small heaps of stones beside the old coffin road along the south side of the Morvern peninsula between Fiunary and the graveyard at Kiel Church (see pp. 66–7).

The placing of cairns at stopping places along the routes of coffin roads was a ritual charged with deep significance and involved a much more deliberate and solemn action than the modern practice of walkers and climbers adding a stone to the cairn at the top of a mountain. Its importance was noted by Norman MacLeod, the mid nineteenth-century Church of Scotland minister whose Reminiscences of a Highland Parish provide rich source material for this book: ‘When the body, on the day of funeral, is carried a considerable distance, a cairn of stones is always raised on the spots where the coffin has rested, and this cairn is from time to time renewed by friends and relatives. Hence the Gaelic saying or prayer with reference to the departed, “Peace to thy soul, and a stone to thy cairn!” thus expressing the wish that the remembrance of the dead may be cherished by the living.’1

The coffin roads which criss-cross the Highlands and Islands come in all shapes and sizes. Some are relatively short and simple, connecting a township with its nearest graveyard. Others are much longer and more complex, involving crossings of lochs and the sea, as in the routes by which coffins were taken for burial on Iona, which involved both long overland walks and one or more journeys by boat. The places at which coffins were loaded onto boats and unloaded were often called either port nam marbh (the port of the dead) or carraig nam marbh (the rock of the dead), from the Gaelic word marbh meaning a dead person or corpse. Port nam Marbh is found as a placename on the north-east coast of Islay, on the south-west side of the Kintyre peninsula just north of Campbeltown Airport, near Kilchoan on the Ardnamurchan peninsula and near Castlebay on Barra. Carraig nam Marbh near Kilninver on Loch Feochan is where coffins brought via several routes across the mainland were loaded onto boats for passage to Iona, some travelling there directly and being landed at Port nam Mairtear (now known as Martyrs’ Bay), others going via Mull, where they were unloaded at Port nam Marbh on the northern side of the entrance to Loch Spelve.

There is one striking characteristic that most coffin roads have in common: they tend to go from east to west. There are practical, cultural and spiritual reasons for this. On islands like Harris, Barra and Eigg, the east coast was often too rocky and barren for any grave to be dug and so those who died there had to be taken for burial in graveyards on the west coast machair, with its deep and easily dug sandy soil. Graveyards were often sited near a loch or on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean, for reasons that will be explored later in this book, with bodies being taken to them from the more inland easterly regions. Highland and Hebridean people desired if possible to die and certainly to be buried in the west, the place of the setting sun. They were by no means unusual in having this desire. There was a widespread belief in many early cultures and civilisations that the abode of the dead lay beyond the setting sun in some place far off to the west. In Homer’s Iliad it was described as being situated in the far west beyond the River Oceanus which was thought to encircle the earth. Celtic mythology shared the Ancient Greek idea of islands of the blessed, heavenly realms lying far out in the western seas. These were the perceived location of the next world, variously described in Gaelic as Tír na nÓg (the land of eternal youth), Tír na mBeo (the land of the living), Tír fo Thuinn (the land under the waves) and Tír Tairngire (the promised land) and seen as lying beyond the setting sun far out in the western sea. Christianity did not dispel this notion, as popular stories like the Voyage of St Brendan testify, and the Hebridean islands continued to be favourite places to be buried throughout and beyond the Middle Ages, with Iona being pre-eminent among them. The body’s final journey, like that of the soul, was more often than not a journey to the west.

Numerous superstitions attached to the coffin roads and many stories centred on them. There was a belief among some Highlanders that if the coffin touched the ground, the spirit of the deceased would return to haunt the living. For this reason, coffins would be rested on the cairns erected at stopping places. Coffins were generally carried with the corpse’s feet facing away from home to avoid the possibility of the spirit returning to haunt it, and coffin bearers took care not to step off the path onto neighbouring farmland lest the crops should be blighted. The somewhat circuitous and meandering route taken by some coffin roads was sometimes explained by a desire to frustrate spirits, which were known to like to travel in straight lines, and a similar reason was given for their propensity to cross running water, something that spirits were thought unable to do. Coffin roads were commonly associated with premonitions and omens of death, known in Gaelic as manadh air bàs. Those gifted with second sight had premonitions of ghostly funeral processions along them which proved to be accurate predictions of future deaths. There is at least one well-documented instance of a walker traversing what had previously been a coffin road and experiencing a frightening and graphic vision of a bloody massacre which he described as a ‘backward glimpse into a blood-stained page of Highland history’ (see pp. 118–19). There are also stories of people being carried in coffins when they were still alive. One such involves a funeral procession along the Harris coffin road. When the bearers stopped for a rest, they heard a noise from inside the coffin. They opened it and found that the person inside was still alive, so she was carried back to the east coast. These and other stories and superstitions are the subject of Chapter 7.

There are some wonderfully detailed and evocative accounts of funeral processions along Highland and Hebridean coffin roads, most of them dating from the nineteenth century, which was perhaps their heyday, although they were in existence long before then and some continued to be used into the early years of the twentieth century. Several of these accounts will feature in the pages that follow, but to give an early taste of what journeys along a coffin road could be like, here are the recollections of Dr John Mackenzie, doctor and factor at Gairloch, of two contrasting funeral processions in which a coffin was carried many miles through the remote north-west Highlands in the early 1830s. The first was conducted ‘in the old, old way, with whisky flowing like water’. The laird of Dundonnell had died in Edinburgh. His body was taken by sea to Inverness and then by horse and cart to Garve, where the road ended.

At that spot it was met one evening by the whole of the adult male population of the Dundonnell estate. They were to start carrying the corpse early the following morning. There was no place where even a twentieth part of this crowd could sleep, so they all sat up through the whole of the night drinking themselves drunk, as there was any amount of drink provided for them, though probably but little food! Early in the morning a start was made by the rough track – the Diridh Mor – which led to Dundonnell, some twenty-five miles away. The crowd of semi-drunken men had marched several miles of the way, when one of the mourners, who was rather more sober than the rest, suddenly recollected that they had no coffin with them, they having left it behind them at Garve, and so back they all had to trudge to fetch their beloved laird.2

The other procession recalled by John Mackenzie was planned with military precision and could not have been more different. It involved the conveyance of the body of Lady Kythé Mackenzie, who had died in childbirth at the age of 23 in Gairloch where her husband was laird, for burial at Beauly Priory more than 70 miles away. In the absence of roads suitable for wheeled vehicles, Dr Mackenzie himself, acting in his capacity as the deceased’s brother-in-law, resolved that the coffin should be carried shoulder-high by parties of men from the estate and the parish. He selected 500 men from more than a thousand volunteers for the task, which involved three days walking with the coffin and then three days walking back and so the loss of a week’s work and wages.

I picked out four companies of one hundred and twenty-five strong men, made them choose their four captains, and explained clearly to them all the arrangements. I was to walk at the coffin foot and Frank [Lady Kythé’s husband] at the head all the way to Beauly, resting the first night at Kenlochewe and the next night at Conon, say twenty-four miles the first day and forty the second; the third day we were to reach Beauly and return to Conon, say nine miles. I sized the companies equally, the men in one company being all above six feet, and the others down to five feet nine or so. I had a bier made so that its side-rails should lie easily on the bearers’ shoulders, allowing them to slip in and out of harness without any trouble or shaking of the coffin. We started with eight men of No. 1 company at the rear going to work, four on each side; the captain observed the proper time to make them fall out, when the eight next in front of them took their place, and so on till all the one hundred and twenty-five had taken their turn. Before all the men in No. 1 company were used up, the second company had divided, and the fresh bearers were all in front ready to begin their supplies of eight; the first company filing back to be the rear company. Thus all had exactly their right share of the duty.

Had the men been drilled at the Guards Barracks in London, it would have been impossible for them to have gone through their willing task more perfectly and solemnly. Not one word was audible among the company on duty, or, indeed, in the other three; every sound was uttered sotto voce in the true spirit of mourning, and I am sure every man of them felt highly honoured by the service entrusted to him. All of us being good walkers, we covered, once we fairly started, about four miles an hour. With the help of Rory Mackenzie, the grieve at Conon, and James Kennedy, gardener and forester at Gairloch, we had prepared plenty of food for the five hundred before we started; the food was carried in creels on led horses for each halt on the way. We had plenty of straw or hay for beds at night, and charming weather all the way.

I doubt if ever a more silent, solemn procession than ours was seen or heard of, and, though it was nearly fifty years ago, I never can think of that wonderfully solemn scene with dry eyes. On the second day, some distance east of Achnasheen, we halted to give the men a little rest and some food. And as I spread them out on the sloping grassy braes above the road and saw food handed round by the captains, it was difficult not to think of the Redeemer when He miraculously fed the thousands who came to Him in a wilderness probably not very unlike the bleak Achnasheen moor. Before we moved away again every man had added a stone to the cairn on the spot where the coffin had rested.

Among those five hundred surely there were some not faultless in head or heart, yet sure I am that had more than a word of kindly thanks been offered to any one for his loss of a week’s work and about one hundred and forty miles of most fatiguing walking, it would have fared ill with the offerer. Every man was there with his heart aching sadly for us. All were substantially and well dressed in their sailor homespun blue clothes, such as they may be seen wearing going to or returning from the herring-fishing. They were all dressed alike and quite sufficiently sombre for mourners; not a rag of moleskin or a patched knee or elbow was visible; all were in their Sunday-best clothes.3

Those two accounts reflect the very different ways in which death was approached by Highlanders. For some, it was an occasion for irreverent revelry and drunkenness, both during the wake that followed immediately after someone died and at the funeral. For others it was a matter of the utmost solemnity. These two responses could co-exist at the same time, as evidenced in some of the other accounts of funerals which will appear later in this book. They point to the mixture of ritual, respect, emotion and excess which surrounded death in the Highlands and the Hebrides. John Mackenzie’s recollections also point to the huge number of people who took part in Highland funerals and the processions along the coffin roads. These were major public occasions which involved the whole community and which were remembered for years afterwards, becoming the subject of numerous stories and legends.

The ubiquity and the significance of the coffin roads provide an eloquent testimony to several key features of West Highland and Hebridean culture and religion. Perhaps the most striking, still evident today, is the desire to be buried among one’s ancestors and in the place where family members had rested for generations. Those born in the Highlands and Islands often left home and travelled far away to seek their fortunes, not returning to their place of birth in their lifetimes. In death, however, they were determined to return and it was their last journey along the coffin road that brought them home. This characteristic was eloquently described by Norman MacLeod:

The Celt has a strong desire, almost amounting to a decided superstition, to lie beside his kindred. He is intensely social in his love of family and tribe. It is long ere he takes to a stranger as bone of his bone and flesh of his flesh. When sick in the distant hospital, he will, though years have separated him from home and trained him to be a citizen of the world, yet dream in his delirium of the old burial-ground. To him there is in this idea a sort of homely feeling, a sense of friendship, a desire for a congenial neighbourhood, that, without growing into a belief of which he would be ashamed, unmistakably circulates as an instinct in his blood, and cannot easily be dispelled. It is thus that the poorest Highlanders always endeavour to bury their dead with kindred dust. The pauper will save his last penny to secure this boon.4

The desire to be buried among one’s ancestors in the consecrated ground of a graveyard was reinforced by a widespread belief in the Christian doctrine of a day of resurrection when the dead would rise from their tombs and assume new bodies to enter the new heaven and new earth promised in the biblical Book of Revelation. This meant that it was important that the whole body was laid to rest in the graveyard with no parts left missing. Among the stories about the coffin roads of the north-west Highlands collected by Archibald Robertson, a Church of Scotland minister who was the chairman of the Scottish Rights of Way Society and is generally regarded as the first person to have climbed all 282 Scottish Munros, was one about an unusual journey made in 1894 on the track from Glen Garry to Glen Moriston. An inhabitant of Glen Moriston had been staying in Invergarry when he had an accident which necessitated the amputation of his leg. ‘His brother came across and carried the leg over Ceann a’ Mhaim and buried it in the old graveyard where they would all one day rest. This shows what store the old Highlanders laid on their being buried, as far as possible, whole and intact, so that at the resurrection they would arise perfect and entire.’5

The involvement of family members – in this case, a brother – is significant here. In most Highland and Island funerals, it was members of the family of the deceased who undertook all aspects of the mourning rituals and preparation for the funeral. They hosted and provided refreshments for the wake, and organised and supervised the carrying of the coffin, as Dr John Mackenzie did for his sister-in-law, and the digging of the grave, which was often undertaken by neighbours and friends. They also generally presided at the burial, which was usually conducted without the presence of a clergyman, almost invariably so in Protestant communities.

The often long and arduous procession along the coffin road by which the deceased was taken home, carried and accompanied by family members and by many if not all of the local community, symbolised and underlined the idea of death as a journey. The passage from this life to the next was seen as a gradual rather than an instant process and marked by a series of rituals. Death was, indeed, prepared for well in advance, with young brides regarding one of their first duties after marriage as being to prepare winding sheets for their own and their husband’s interments. When someone was clearly near death, they were visited, tended and ministered to not just by family members but also by friends and neighbours. Semi-professional mourning women might be brought in to sing the death croon over them and ease their passage into the next world. After death, the body was washed and dressed and left lying prominently in the front room of the house, often with a plate of salt placed on the breast. From the time of death until the interment, which was usually a period of two days and nights, the body was constantly watched over by a family member, with a wake held in the house to which all friends and neighbours would be invited and which often became raucous and exuberant. Once the grave had been dug and the mourners assembled, the funeral procession set off along the coffin road to the graveyard. After the interment, all those present were liberally entertained with drink and food, first around the graveside and then later at some local hostelry or specially erected tent, or if the weather allowed it, in the open air.

These rituals, which will be described in more detail in later chapters, played a key role in easing and facilitating the grieving process. They provided numerous tasks, some of them backbreaking like the digging of the grave and the carrying of the coffin, which occupied people and gave them a purpose and a focus at a time of emotional upset and sorrow. They punctuated the period following death with familiar, reassuring domestic and community activities and created a kind of liminal or threshold space which blurred the hard edges between living and dying and gently eased both the deceased and the mourners into their changed state.

The coffin roads are just part of a wider landscape of death which cannot but strike modern visitors to the Highlands and Islands. Even more ubiquitous and certainly more visible today are the many graveyards and cemeteries scattered across the region which were the destinations of the coffin roads. They are often sited in seemingly very remote places, high up on the slopes of hills or down on the side of a loch or a quiet seashore, sometimes protected from the wind by trees and nearly always surrounded by stone walls. Some are very ancient and virtually inaccessible, like Cladh a’ Bhile at Ellary by Loch Caolisport in mid-Argyll, which has nearly 30 cross-marked stones dating from the seventh and eighth centuries. Many are overgrown, often with the crumbling ruins of a small chapel in their midst, while others are still very much in use and well-tended. Within them, small worn stones decorated with no more than a simple incised cross stand side by side with elaborately carved grave slabs bearing the effigies of soldiers and prelates and massive mausoleums, burial aisles and enclosures erected to house the bodies of the rich and well-to-do, more often than not Campbells.

These graveyards have become important places of pilgrimage. People come from all over the world to visit them in order to trace their ancestors, thanks partly to the growing fascination with family trees and genealogy. Indeed, they have become among the most visited parts of the Highland and Hebridean landscape. Many people enjoy walking around them simply because of their atmosphere and the interesting artwork and inscriptions on their gravestones. We feel a sense of timeless peace and tranquillity as we walk among the ancient lichen-covered tombs which have taken on the character of works of art or historical monuments. Those who erected and engraved them saw them in a very different light. Often marking tragically early diseased and violent deaths, their prime purpose was to remind those still alive of the frailty of our human clay and the reality of mortality. This is why more than anywhere else in the British Isles, the graveyards of the West Highlands and the Hebrides are full of stones engraved with trumpets, hourglasses, skulls and crossbones with their inescapable message, sometimes spelled out explicitly in inscriptions beside these symbols of mortality, memento mori – remember you must die.

Just as with the coffin roads, various superstitions attached to these graveyards. There was a widespread belief that the last person to be buried had to keep watch and look after all those resting there until the next interment took place. This was regarded as an onerous responsibility and on occasions when two burials took place on the same day it was not unusual for each group of mourners to make great efforts, including resorting to physical force, to make sure that they reached the graveyard first so that their loved one was not left with the task of looking after the dead (see p. 74). The sense that the dead are waiting in the graveyard for their families and descendants to join them lingered well into the twentieth century. An old woman in Skye, who was a loyal member of the Church of Scotland, told the Gaelic scholar John MacInnes shortly before her death in the late 1950s that she believed the dead lie waiting in the cemetery ‘longing until the last of the future generations should join them, whereupon their society would be complete’.6

For those aware of these beliefs and traditions, and of the Christian teaching that our condition post-mortem is one of a long sleep until the Day of Resurrection, walking the coffin roads and visiting the graveyards of the Highlands and Islands today may perhaps induce a sense of the lingering presence of the dead. Do they indeed continue in some way to inhabit the physical landscape? This has been suggested in a very interesting way by the Irish theologian Noel Dermot O’Donoghue, who lectured in the Faculty of Divinity at the University of Edinburgh in the 1970s and 1980s, the first Roman Catholic to do so since the Reformation. In his book The Mountain Behind the Mountain: Aspects of the Celtic Tradition he writes about the churchyard in Ireland where his parents were buried:

This is the elemental earth from which I came, as they, my forefathers and mothers, came and to which I too shall return. In a sense these people are not where their bones lie; they are elsewhere, as I too shall be as they place my remains in the element of the earth or the element of fire. Yet the funeral rite speaks of the resurrection of the body as if the whole person somehow awaited resurrection here in this place. There is an ambiguity here that Christian theology, from the time of Saint Augustine until today, has never quite resolved. Are the dead alive in another region, or do they somehow, somewhere await an awakening? Are they still somehow part of nature, or do they dwell in a spirit world which may be near to us but is yet of a totally different substance?7

O’Donoghue points to the way that in folk consciousness the dead are regarded as a lingering presence in the physical landscape, as suggested by such phrases as ‘the good dead in the green hills’ or ‘she is gone to her people’. He quotes Lord Byron recalling his own ancestry in a wild Highland place:

Clouds there encircle the forms of our fathers;

They dwell in the tempests of dark Lochnagar.

O’Donoghue also quotes the great twentieth-century Jesuit theologian, Karl Rahner, who wrote in his book On the Theology of Death: ‘we cannot rule out the possibility that in death the relationship which we have with the world is not abolished, but is rather, for the first time, completed ... through death the soul becomes not a-cosmic but all-cosmic’.8

I will come back to these deep spiritual matters later in this book, just as I will also reflect on the way that Hebrideans and