Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Children's Books

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

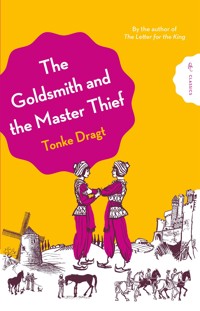

'Wonderful... such a joy' Wall Street Journal 'Like a fairy tale up dream of but have never found' New Statesman Laurenzo and Jiacomo are identical twins, as alike as two drops of water. No one can tell them apart, and no one can split them up. But when tragedy strikes, they must make their own way in the world. Each brother chooses his own path - hardworking Laurenzo learns to make priceless golden treasures, and fearless Jiacomo decides to travel and becomes an unlikely thief. So begins an incredible adventure that will test them to their limits. The twins will face terrible danger, be imprisoned in a castle, sail across the ocean, fall in and out of love, and even becomes kings by mistake. They must use all their talent and wit to survive. Are you ready to join them? Part of the new Pushkin Children's Classics series of thrilling, magical and inspiring stories from around the world, which young readers will return to time and again. Translated by Laura Watkinson. Tonke Dragt was born in Jakarta in 1930 and spent most of her childhood in Indonesia. Her family moved to the Netherlands after the war and, after studying at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague, Dragt became an art teacher. She published her first book in 1961, followed a year later by The Letter for the King, which won the Children's Book of the Year award and has been translated into sixteen languages. Dragt was awarded the State Prize for Youth Literature in 1976 and was knighted in 2001. She died in 2024. Laura Watkinson is a full-time translator from Dutch, Italian and German. She has translated many titles for Pushkin Children's Books, including Jan Terlouw's Winter in Wartime, Tonke Dragt's The Letter for the King and Annet Schaap's Lampie. She lives in Amsterdam.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 502

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

‘What makes The Goldsmith and the Master Thief a joy is its lively spirit… There’s nothing sticky or moralistic here, just great storytelling that happens also to be principled. This is a terrific family read-aloud’ Wall Street Journal

‘Captivating and beautifully written’ Angels and Urchins

‘A richly textured world… fresh and delightful… Children will be enthralled’ Children’s Books Ireland2

3

4

Contents

The First Tale

The Birth of the Twins

Right, now we shall begin. When we reach the end of our story, we shall know more than we know now.

andersen: ‘The Snow Queen’

In Bainu, the beautiful capital city of Babina, there once lived a poor cobbler and his wife.

One morning, two puppies came running into the cobbler’s workshop. They greeted him, barking and wagging their tails, and started playing with the shoes that he was mending.

“What’s all this?” the cobbler shouted. “Away with you!” And he chased them outside.

The next morning, however, the dogs came back, barking and wagging their tails as before, and once again he chased them out of his workshop. But when he joined his wife in the kitchen at lunchtime, the dogs were under the table, eating together from the same plate.

“What are you doing?” he said to his wife. “Are you feeding those animals? They’ve already been into the workshop bothering me twice. Get rid of them!”

“Oh,” said his wife, “but they’re such friendly little things! And have you seen how thin they are? Let them stay. They clearly trust us to look after them.”8

9“Absolutely not,” said the cobbler. “We’re poor and we have a child on the way. There is no way we can have two dogs.”

“But we always have a few leftover scraps that they could eat,” his wife replied. “And they can guard our house. Please, let them stay.”

“As if we have anything that needs guarding!” said the cobbler, but his wife kept on pleading, so he gave in, because he was in fact just as kind-hearted as she was.

So then they had two dogs, which brought them a lot of problems, but also a lot of pleasure.

A week later, the cobbler found a basket outside his door. There were two kittens inside, meowing sadly.

“We have no use for these little beasts,” he said to his wife. “I’m going to get rid of them.”

“No, you can’t do that!” said his wife. “They’re so sweet. Look, they’ve only just opened their eyes. Let’s keep them.”

“Absolutely not!” cried the cobbler. “We’re poor and we’re about to have a child. Besides, we already have two dogs.”

“Cats hardly eat anything though,” said his wife. “And they catch mice.”

Once again, the cobbler gave in, and so they had two dogs and two cats, which gave them a lot of trouble, but also a great deal of pleasure.

Some time after that, the cobbler was hammering away in his workshop when two pigeons came flying in through the open windows and sat on his shoulders, one on each.10

“What do you want from me?” he asked. “I already have two dogs and two cats. And in a few days I’ll have a child too. Away with you! Scram!”

But the pigeons stayed where they were.

Fine then, thought the cobbler. I wonder what pigeon legstaste like.

No sooner had he thought that than the pigeons flew up and away. The cobbler ran outside after them, trying to catch them, but they fluttered up onto the roof of his house.

“Right, then you can just stay up there,” said the cobbler, and he headed back inside and told his wife that there were two pigeons on the roof.

“You mustn’t eat them,” his wife replied. “They came to you of their own free will – and that’s good luck.”

“Two dogs, two cats and two pigeons,” muttered the cobbler. “I wonder what other good luck is in store for us?”

The next night, he received the answer to his question, when his wife gave birth to twins, two big and healthy baby boys.

“Well, well,” said the cobbler the next morning, as he stood beside the bed where his wife lay, tired and happy, with a child in each arm. “Twins! And their birth was foretold by extraordinary events. So our sons are sure to become extraordinary children.”

The boys were christened and given the names Laurenzo and Jiacomo.

“We don’t have any money for christening gifts,” said their parents, “but we’ll still give them something. They shall each have a puppy, a kitten and a pigeon. Don’t we make a lovely family?”11

Laurenzo and Jiacomo grew up in good health, and they were as alike as two drops of water or two grains of sand. When they walked together through the streets of Bainu, with their dogs at their heels, their pigeons on their shoulders, and their cats in their arms, no one knew which was one and which was the other. Only their parents could tell them apart – not because of the way they looked, but because of how they behaved.

The brothers were inseparable, and they enjoyed their time together. They were poor, but how many boys are there who have not only a dog, a cat and a pigeon, but also a twin brother to play with? And what better places to play than in the narrow, winding streets and alleys of Bainu, or on the big square in front of the royal palace or in the rolling fields outside the city walls?

The twin brothers had lots and lots of interesting experiences when they were still little boys, and I shall tell you a story from that time.

The Second Tale

To School

“You look exactly the same as me, as you wear the same clothes, and the same animals follow the two of us, both you and me.”

grimm: ‘The Two Brothers’

The twin brothers led a free and happy life until one day their father called them to him and said: “Boys, you’re nearly seven years old now, and it’s time for you to learn something. I cannot give you wealth, but I can make sure that you learn to read, write and do sums. That is a wealth that you will never waste or lose. So tomorrow the two of you are starting school at the Brown Monastery.”

Laurenzo and Jiacomo stared at him. School? Did that mean they would no longer be free to wander the streets and play all day long? Some of their friends had recently started school. They spent all day inside, sitting on hard wooden benches, locked up like birds in a cage.

“Oh, Father, please don’t send us there!” they both cried.

The cobbler looked at his sons seriously. “You’re big boys now,” he said, “big enough to understand that school is good for you. When you grow up, you’ll be happy to have learnt something – and to know more than I know myself.”

“We’re going to be cobblers, like you,” said Laurenzo. “So we don’t need to go to school.”

14“But maybe later you’ll want to be something different from your father,” replied the cobbler. “And just think how nice it will be when you can read letters from people and write letters back to them too.”

“And our pigeons can deliver them for us,” said Jiacomo.

“Exactly. Do your best, and you’ll soon be clever boys who will make me and your mother proud.”

The boys did not reply. They really did want to please their parents, but…

“And you’ll have Sundays off,” said their father, as if he had guessed what they were thinking. “But anyway I’m sure you’ll enjoy school.”

So it was settled. But that night, in bed, the brothers lay awake for a long time, talking. They both agreed that school sounded like a very bad thing indeed.

“And it’s every day too!” said Laurenzo with a sigh.

“If it was just the morning, or just the afternoon!” said Jiacomo.

“I’ve heard that the teacher sometimes makes you write the same word out a hundred times,” said Laurenzo. “What’s the point of that?”

“I have an idea!” cried Jiacomo suddenly.

“Sssh!” whispered Laurenzo. “You’ll wake Mother and Father.”

“We won’t go to school every day,” Jiacomo whispered back. “We’ll go one day and not the next – that’ll be enough.”

15“But we can’t do that,” said Laurenzo. “You get punished if you miss a day.”

“Ah, but we can do it completely differently,” said Jiacomo and he began to whisper his plan.

“Will it work?” wondered Laurenzo.

“Of course it will!”

Then they heard their mother’s voice. “Boys, are you still awake?”

Then there was silence.

The next morning, their mother took a long look at the two of them. “Good. You both look nice and neat,” she said. She gave them each a bag of sandwiches. “That’s for lunchtime,” she said. “And here’s an apple for each of you.”

Their father patted them both on the shoulders before heading to his workshop. “Do your best – and work hard,” he said.

Then their mother got ready to take them to school.

“Oh no, there’s no need to come with us, thanks,” said Laurenzo. “We already know the way.”

“Just this first time,” their mother said.

“All of the other boys walk to school by themselves,” said Jiacomo. “We can go with Antonio from the tavern. He’s been at school for a while now.”

Their mother smiled. “Oh, the two of you are getting so big,” she said, a little sadly. “Fine then, if you’d rather go on your own. No, Jiacomo, the animals have to stay at home.”

“You mean the dogs can’t come with us?” asked Laurenzo.

“No,” their mother said firmly. “Dogs don’t belong in a classroom.”

16And so the two boys went on their way. Their mother stood in the doorway and waved them off. At the end of the street, Antonio joined them. And as they reached the next street, their dogs came running after them. They had slipped out when the boys’ mother was not watching. The twins told them to go back home, but the animals did not listen.

“They’ll just have to come with us,” said Laurenzo. “Do you think that’s allowed?” he asked Antonio.

Antonio looked doubtful. “The monks might not mind one dog,” he said, “but I think two might be a problem.”

“But only one of the dogs is going to school,” said Jiacomo.

“Why? Are you sending your dog home?” asked Antonio.

“No,” said Jiacomo and he started to tell Antonio his plan. “You have to help us,” he said, as he finished. “And you mustn’t tell anybody about it. Not a soul.”

Antonio gazed at the brothers in awe. “I wish I had a twin brother too,” he said with a sigh.

A quarter of an hour later, school began. The teacher of the younger pupils, a big monk in a brown habit, stood at the door, smiling and welcoming all the children.

“Aha,” he said, “I see we have a new student.” Leaning over to a young boy with a dog, he asked, “What’s your name, lad?”

“I… I’m Lau… Laucomo. Laucomo, the son of Ferdinand, the cobbler.”

“Welcome, Laucomo,” said the monk cheerfully. “Are you a friend of Antonio’s?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Can he bring his dog, Brother Thomas?” asked Antonio. 17

“His dog? Well, I suppose so, if it’s well behaved. But, Laucomo, I thought you were coming with your brother. Ferdinand mentioned two sons.”

“I… I don’t have a brother,” said Laucomo, his face turning red.

“Oh,” said Brother Thomas, scratching his head, “then I must be mistaken.”

“Yes, sir,” said Laucomo.

“That’s right, Brother Thomas,” said Antonio. “He doesn’t have any brothers.”

“Go on inside,” said the monk. “You can sit next to Antonio, Laucomo.”

When the boys were in their seats, Antonio whispered to his neighbour: “It worked!”

18Laurenzo, because that, of course, is who it was, did not reply. He felt a little uneasy. He was missing his brother too. Antonio was nice enough, but it should have been Jiacomo sitting beside him.

Meanwhile, Jiacomo was walking across the market square with his dog, singing a happy song. He was very pleased with his plan. He and Laurenzo were going to take it in turns to go to school. That way they would learn just enough and they could have plenty of time to play outside too. At school, everyone would think there was just one boy, Laucomo. Yes, he certainly had come up with an excellent plan! He thought about what he was going to do today. He could play anywhere, as long as it was not too close to home or to school. But how was Laurenzo doing? Jiacomo missed him – until today the two brothers had always played together.

A week later, Brother Thomas said to Brother Augustine, who taught the older students: “That Laucomo is a nice boy, but I don’t know quite what to make of him. One day he behaves completely differently from the next. And he can be so forgetful! Sometimes he can’t even remember what I told him just the day before.”

Which goes to show that the big monk was an observant man.

So far everything had gone as planned. The only problem was that the twin brothers often spent a long time talking in bed at night, and so their father sometimes became angry with them. But how else were they supposed to tell each other what they had been up to all day?

19“We learnt a song today,” said Jiacomo one night, “about riding on a horse.” He sang it quietly to his brother. “And we did the letter T. It’s really easy. Do you remember it?”

“Yes,” said Laurenzo. Jiacomo had already taught him the letter T on the way home.

“What did you do today?” asked Jiacomo.

“I went to the market with Piedro. And then we played by the river. But it was boring. Piedro’s such a baby. He’s only just five.”

“School’s boring too,” said Jiacomo with a sigh. “And I had an argument with Antonio. He’s so stupid. I’m sure he’s going to give us away.”

“The letter T,” said Laurenzo, “T… T… Two… Twins, that begins with a T too. Two twins. Do you like it? Being on your own?”

“No,” said Jiacomo. “Not at school.”

“And outside school?”

Jiacomo did not answer for a while. Then he said, “Well, sometimes it’s fun at school. But having to go there every day? No, I don’t like that at all.”

“But being on your own every day is no fun either.”

“We have lots to tell each other though.”

Then they heard their father’s voice: “If you two don’t settle down, I’ll give you both a whack on the behind!”

The boys were silent. For a while. Then Jiacomo whispered: “You’re right. I don’t like it, not one bit.”

A week after that, Brother Thomas said to himself: “That Laucomo! Why does he write neatly one day and then make a mess the next day? Why does he know his times tables one 20day and forget them the next? Sometimes he does one thing well, and then he does another thing excellently, but there’s never a week goes by when he does consistently well at the same things.”

He looked at Laucomo. The boy was sitting next to Antonio in the front row, and his dog was lying under the desk. Brother Thomas could see that Antonio was whispering something to him. Laucomo did not answer. So Antonio nudged him and repeated his question.

“Hey,” he whispered, loudly enough to be heard, “are you Laurenzo or Jiacomo?”

Brother Thomas raised his eyebrows. “Are you talking, Antonio?” he said. “Be quiet and get on with your work.” But he wondered what Antonio could have meant.

However, he was even more surprised when he spoke to Brother Augustine after school, who had taken his classes out for a walk that afternoon.

“You need to keep an eye on that Laucomo,” said Brother Augustine. “I saw him on the street this afternoon, during school hours!”

“You must be mistaken,” said Brother Thomas. “He’s been sitting in the front row all day.”

“I’m sure I saw him,” Brother Augustine insisted. “The boy with the dog.”

Brother Thomas scratched his head. Something was beginning to dawn on him. “But that’s absurd,” he muttered. “Hmm, I shall have to keep a very close eye on that lad.”21

Meanwhile the twins were sitting on the step outside their house, with their pigeons on their shoulders, their cats on their laps and their dogs at their feet, happy to be together again.

“How was it today?” asked Jiacomo.

“You didn’t miss much,” said Laurenzo. “We didn’t do anything new. Oh yes, don’t tell Antonio which one of us you are. He can’t keep track of it, the dope!”

“Boys! Dinnertime!” called their mother.

“How was school today, Jiacomo?” she asked, when they were sitting at the table. “You haven’t said anything about it yet.”

“But Laurenzo already told you everything,” said Jiacomo.

Which was completely true.

22Laucomo, thought Brother Thomas, as he stood, large and imposing, at the front of the classroom. Laurenzo or Jiacomo. Most amusing. Then he raised his voice. “Laurenzo!” he called.

The boy on the left in the front row looked up. It was Jiacomo, but each of the twins also answered to the other’s name.

The monk came and stood beside him. Jiacomo leant further over his slate. He felt rather uncomfortable. If only he and his brother had never started all this!

“Tell me, boy,” said the monk. “Yes, now do tell me, what is your name? Are you Laurenzo? Or are you… Jiacomo?”

Jiacomo dropped his pencil. With a red face, he looked up.

“I…” he began hesitantly. Then quickly he said: “Both. I’m both. My full name is Laurenzo Jiacomo.”

“Hmm,” replied Brother Thomas, narrowing his eyes. “That’s quite a mouthful, eh?” He turned around and began walking along the rows of desks.

Jiacomo picked up his pencil, but he could not keep his mind on his work. What had he gone and done now? He had lied to Brother Thomas! But he had of course been lying all along, ever since his first day at school.

Antonio nudged him. “Good one!” he whispered. “But which one are you? Laurenzo or Jiacomo?”

“You should know,” Jiacomo whispered back. “I’m not telling you.”

“Bah, you’re being just like… just like your brother yesterday. Watch it, or I’ll say it out loud! Which one are you?”

“Sssh!” whispered Jiacomo.

“Quiet, boys!” barked Brother Thomas.

Startled, the boys pretended to go on working.

23A little later, the monk had the slates collected. Then he went and stood at his lectern and said: “It’s another ten minutes until you can go home. Now listen carefully, and I’ll tell you a story. It’s an old, old story, from the days when people still believed in all kinds of different gods.

“In Greece, there once lived two brothers. Castor and Pollux were their names. They were born on the same day, and so they were twins. Their father was Zeus, the ruler of the Greek gods, and their mother was an ordinary woman. The two brothers were so alike that no one could tell which was one and which was the other, and yet there was a difference between them. Pollux was immortal, just like his father, who was a god – so he would live for ever and ever and never die. But Castor was mortal, just like his mother and every other human in the world.

24“The two brothers were inseparable and they performed many brave deeds together.

“But alas, a war began, and Castor was struck by a spear and he died in battle. When Pollux saw him lying there dead, he was heartbroken, and he cried: ‘What do I care about living for ever if my brother is not with me?’

“Now the ancient Greeks believed that the dead went to a land that was under the earth – a cold and dark land, the Underworld. So that was where Castor went, and Pollux remained behind, all alone.

“But Pollux did not want to be alone, and so he went to his father, Zeus, who was sitting on his throne of clouds.

“‘Oh, Mighty Father,’ he said, ‘why did Castor have to go to the Underworld when I do not? Can’t you bring him back to life and return him to me?’

“‘That is impossible,’ said Zeus. ‘Those who have descended into the Underworld must remain there. You are immortal and so, if you wish, you may live with the gods in Heaven and be happy for evermore.’

“‘But I can’t be happy if Castor is not with me!’ Pollux wailed.

“‘Fine,’ said Zeus, ‘then you may choose. Do you want to live for ever with me and the other gods, or do you want to be with your brother in the dark land under the earth?’

“‘I would rather be with Castor in the Underworld than alone in Heaven, no matter how beautiful it might be,’ replied Pollux.

“‘You are a loyal brother,’ said Zeus. ‘And so this is what we will agree: you may spend one day with Castor in the Underworld and the next day you can both be with me in Heaven.’

25“And that is what happened. From then on, the twin brothers spent one day in the Underworld and the next day in Heaven, but they were always together and so they were happy.”

Brother Thomas looked around the class as he finished his story: “You might think this is an odd tale. But there is something very fine about it – and that is the loyalty between the two brothers, who were prepared to share with each other even those things that were not pleasant or enjoyable.” His gaze rested for a moment on “Laucomo”. Then he said: “That’s it for today, boys and girls. You can go home now.”

Later, Laurenzo and Jiacomo were sitting on the step outside their house again, and Jiacomo was telling his brother about Brother Thomas’s story.

When he had finished, they both sat in silence. After a while, Jiacomo said: “Shall we stop it now?”

“Yes,” replied Laurenzo. Then all was silent again.

Until they both spoke at the same moment. “What do you think Brother Thomas is going to say?”

“You’ll be punished,” said Jiacomo.

“So will you,” said Laurenzo. “We both played truant.”

“Maybe he already knows,” pondered Jiacomo.

“The punishment won’t be so bad if we’re together,” said Laurenzo.

“It still won’t be much fun though,” said Jiacomo.

“No,” agreed Laurenzo.

“But then we’ll be able to have such a good time together!”

26When Brother Thomas came into the classroom the next morning, he froze. He had been expecting it, but still, for a moment, he was stunned. The children were all giggling. Antonio was the only one who looked a bit glum, because he was no longer sitting next to his friend “Laucomo”.

“What’s all this?” the teacher cried in a loud voice. “Is there something wrong with my eyes? Am I seeing double? Or has Laucomo really split in two?” And he added: “And he even has two dogs!”

The twins, sitting in the front row, looked at him with a mixture of amusement and fear.

“I see,” said the monk. “So you’ve been sharing the work, have you? Then tell me why you’ve decided to come together today.”

27“It’s more fun when there are two of you,” said the brothers.

“Hmm,” said Brother Thomas. “You naughty little truants! But the two of you belong together, eh? You’ve realized that now. And school’s not really that bad, is it?”

The boys shyly shook their heads.

Brother Thomas burst out laughing, his belly shaking, and the whole class laughed along with him. “But tell me,” he asked, “which one of you is Laurenzo and which is Jiacomo? Or do I have to guess?”

“Yes, guess!” the class cried.

“Let me see,” the monk said to the twins. “Who can tell me the story I told yesterday?”

“Me! Me!” cried both Laurenzo and Jiacomo.

Brother Thomas sighed. “How will I ever know who is one brother and who is the other?” he wailed, putting on a sad face.

“Jiacomo told me the story,” said Laurenzo.

“Excellent! Now I know who’s who. And by the end of the week, I won’t make any more mistakes.”

But no matter how clever Brother Thomas was, he still got it wrong, many, many more times! 28

The twin brothers Laurenzo and Jiacomo had a happy and carefree childhood. But when they were fifteen years old and had just become apprentices to their father, a contagious disease broke out in Bainu, and both of their parents died, one after the other. They did not even have time to grieve properly, as their parents’ illness had cost the family so much money that they had to sell the cobbler’s shop. And when they had done that, they were penniless.

“Luckily we still have each other,” they said. “We must look for a job so that we can earn our living.”

However, that turned out to be more difficult than they had thought. There were plenty of people who wanted a servant. But no one needed two.

“There are no jobs here in Bainu for the two of us together,” Laurenzo said to Jiacomo. “What shall we do?”

“We belong together and we shall stay together,” replied Jiacomo. “Let’s leave Bainu and go out into the world. We’re sure to find work somewhere.”

“You’re right,” said Laurenzo. “Why should we stay here?”

So the brothers packed up their few belongings. They found homes for their cats and pigeons with some kind neighbours. Only the dogs were allowed to go with them. Then they said farewell to their friends and, with heavy hearts, left the city that was so dear to them.

29

30

The Third Tale

Out into the World

We are brothers, as you can see.

But when shall I see him – and he see me?

A Dutch folksong

So the twin brothers headed out into the world. And once they were outside the city walls, their sadness began to give way to a feeling of anticipation. Every twist in the road might lead them to a surprise, and behind every hill a beautiful view might be hidden.

They travelled through Babina, along the banks of the River Grior, imagining that they might encounter adventure at any moment. Their dogs trotted along beside them, and back and forth, wagging their tails and covering twice the distance that their masters travelled.

At first the brothers enjoyed their freedom so much that they did not even think about looking for work. There was always something for them to eat and they could easily sleep out in the open, as it was summer. But when autumn came, and it grew colder, they both agreed that they should find a job.

But alas, they had no more luck finding a job together than they had in Bainu!

32One day, they came to a place where the road split in two. There was a shabby little hut nearby, and they were tired, so they decided to knock on the door and ask for hospitality. They found an old pedlar living there, who welcomed them warmly and invited them to share his meagre meal. Before long, the brothers were telling him all about themselves and complaining that they had been unable to find a job that would allow them to stay together.

“There’s only one option,” said the pedlar. “You’re going to have to split up.”

“But that’s exactly what we don’t want to do,” said Jiacomo.

“We’ve always been together,” said Laurenzo.

“That was fine when you were children,” said the pedlar. “But now that you’re almost adults and there’s no other way, you will each have to choose your own path.” He looked at Laurenzo and asked: “What would you like to do? What kind of work appeals to you most?”

Laurenzo thought about it. “I believe that I would like to make something,” he said then. “Not shoes, like our father, but objects made of silver and gold. Vases and bowls and beautiful jewellery.”

“And what about you?” the pedlar asked Jiacomo. “Do you share your brother’s wish?”

“No,” said Jiacomo after a pause. “I love beautiful things too, but I don’t think I could make them, not like Laurenzo. I don’t really know exactly what I’d like to do. I would just like to travel the world, and go on long journeys, and to spend some time here and some time there. And to discover new things, and to meet all kinds of people and to have adventures – that all sounds very fine to me.”

33“You see?” said the pedlar, looking at one brother and then the other. “You see that you’re not the same, even though you’re brothers and as alike as two drops of water? So each of you needs to choose his own path.”

He saw the worried looks on their faces and smiled at them kindly. “Never mind,” he said. “This is not goodbye for ever! There’s a fork in the road nearby. Each of you should go his own way and agree to meet here again in a year’s time.”

The brothers looked at each other as they considered his words.

“Take my advice,” said the pedlar. “Look, I have a knife here. I’ll drop it and whoever the tip is pointing at should take the left path. Whoever is facing the handle should take the right. But you must both make sure to return here in a year’s time. And what you do after that – well, we’ll cross that bridge later. So what do you think of that idea?”

“We’ll take your advice,” said the twins. “If there is no other way, then we shall part company.”

34The pedlar dropped the knife on the ground, and it landed so that Laurenzo should take the right-hand path and Jiacomo the left.

The next morning, the two brothers said goodbye to their host. They said a very fond farewell to each other and promised once again to meet at the same place in a year’s time. Then each of the brothers went his own way, Laurenzo to the right and Jiacomo to the left.

Laurenzo’s path took him through a beautiful hilly landscape. For the first two days, he met no one, but on the third day he caught up with an old man, who was struggling to lug a big sack. Laurenzo asked him if he could carry the sack for a while, and his offer was gratefully accepted.

“Thanks. I’m not getting any younger,” said the man, “and it was starting to become a little too heavy for me. My horse stumbled yesterday and broke its leg, so I had to continue on foot. Where are you heading?”

35“Wherever the road takes me,” replied Laurenzo.

“Then you will end up in Sfaza,” said the man. “What are you going to do there?”

“Look for a job,” replied Laurenzo.

“What kind of job?”

“I don’t know yet. Maybe working with a goldsmith.”

“A goldsmith? Why?”

“Because that is the trade that appeals to me most,” said Laurenzo.

“But why do you need to go to Sfaza for that?”

“Oh, that’s purely by chance,” replied Laurenzo. “Fate showed me this road. I hope I will find my fortune there.”

“Then let us travel together,” said the old man. “I love company. Or is your dog enough company for you?”

“I’d be happy to be your travelling companion,” said Laurenzo, who had been feeling rather lonely since saying goodbye to his brother.

So the two of them travelled onwards, with Laurenzo carrying the sack.

When evening fell, they came to an inn, and the old man said: “You are my guest, and I shall treat you well, as you carried my sack. And then you may have something from the sack as payment for your help.”

Laurenzo assured him that he did not expect a reward, but the old man said: “I know that! But I would like to give you something.”

When they had eaten dinner and were sitting in the room that the old man had rented for the two of them, he opened up the sack and, to Laurenzo’s surprise, took out the most 36valuable of objects – silver necklaces, cups and bowls of beaten gold, elegantly decorated rings and brooches, set with precious stones. “I’m going to sell them in Sfaza,” said the old man. “But first you may choose something for yourself. Do you like them?”

“They’re beautiful,” said Laurenzo. “Far too beautiful for me.” And he wondered how his travelling companion, who did not look at all wealthy, had come by these costly objects.

“I made them all myself,” said the old man, as if he had read his mind. “I am, in fact, a goldsmith by trade.”

“A goldsmith!” said Laurenzo. “And is that a difficult trade?”

“Only as difficult as any other job,” said the man. “If you have a talent for it, that is.”

“There are lots of goldsmiths in Bainu too,” said Laurenzo. “One of them is very famous. His name is Master Philippo and he has even worked for the king.”

“Do you know this Master Philippo?” asked the old man.

“No,” replied Laurenzo. “Although I have heard a lot about him. I have only seen his shop from outside.”

“Well, then now you do know him,” said the old man. “I am Philippo the goldsmith, and I come from Bainu. So tell me which of these things you think is most beautiful.”

“This one,” said Laurenzo, pointing at a small bowl. “But I couldn’t possibly accept it. It’s far too beautiful and precious for me.”

“Listen to me,” said Master Philippo. “I know you a little now, and you seem like a good lad. And you also have a good eye, as that bowl is indeed the finest of all the objects in my sack. So if you don’t wish to accept anything from me, then I have another proposal for you. Become my apprentice. If 37you have a talent for the job, then an excellent future awaits you. What do you say?”

“Oh, Master Philippo!” cried Laurenzo. “There is nothing I would rather do! I truly believe I found good fortune on my path today.”

“Excellent,” said the goldsmith. “I have to go to Sfaza first to sell these things, and then we’ll travel back to Bainu, where I work and live. Is that what you would like to do?”

“Of course,” said Laurenzo. “Bainu is the most beautiful city in the world.”

“You’re right,” replied Master Philippo, “although you can’t actually know that for sure, as you’ve seen hardly anything of the world. And now it’s time to sleep, as I’d like to make an early start tomorrow. I’ll be a good master, but you’ll need to work hard.”

“I’m not scared of hard work,” said Laurenzo. He could not get to sleep at first, as he was so excited about the future that awaited him. The only shadow over his happiness was that Jiacomo could not be with him. But, he consoled himself, we’ll see each other again in a year’s time.

Jiacomo had taken the left-hand path. Although he was sad about saying goodbye to his brother, he was still singing. It was a song he had made up himself:

“Oh, when will we two see each other again?

When will we meet once more?

When will we see each other again?

And will there be sun?

Or will there be rain?”

38The first two days, like his brother, he met no one. On the third day though, he came to a sheep pen. He asked the shepherd if he needed any help.

“Bah!” said the shepherd, scornfully spitting on the ground. “A boy like you soon tires of looking after sheep and then he runs away and abandons the poor creatures. Go on! Clear off!”

As Jiacomo walked on, he thought to himself: I hope everyone around here isn’t that unfriendly. I’ve been walking for three days now and I still haven’t found a job. Maybe I should just go back to Bainu. Then he stopped.

No, he thought. I’ll follow this path to the end. I already know what lies behind me. What lies ahead is a surprise.

So he walked on, followed by his faithful dog. And he came to a vast plain covered with yellowish grass, where rocks lay scattered around, as if thrown by giants. This was the Plain of Babina, where there was dense fog for half the year, and a stormy wind blew for the rest of the time – a hostile, mysterious region, where few people lived. Travellers who had to cross it did so as quickly as possible, afraid of fog and storms, of robbers and will-o’-the-wisps.

Jiacomo headed across that desolate plain. First there was a storm, then mist and finally he got lost. He wandered around for three days, with no idea where he was going, and he thought to himself: I was longing to travel and to see the world, but that’s no good if you never meet anyone to talk to.

Three days later, the fog lifted, and he saw a man walking ahead of him in the distance. He stepped up his pace and soon caught up with him. He was a big, dark man, and he was 39struggling to carry a large sack. Jiacomo greeted him and said: “Would you like me to carry your sack for a while?”

“Yes, please,” said the man, “I’ve already walked a long way. My horse broke its leg so I had to put it out of its misery. Where are you going?”

“Wherever the road takes me,” replied Jiacomo. “But right now it doesn’t seem to be taking me anywhere.”

“If you tell me where you want to go, I’ll point you in the right direction,” said the man. “You can go to Bainu, Forpa or to Talamura, whichever you prefer.”

“Bainu – that’s where I came from,” said Jiacomo. “Which is better, Forpa or Talamura?”

“I can’t tell you that,” said the man. “I don’t know what you want to do.”

“Look for a job,” said Jiacomo.

“What kind of job?” asked the man.

“I don’t know yet,” replied Jiacomo.

“What would you prefer,” asked the man, “an ordinary, dull job, or one that’s full of adventure?”

“Adventure, of course,” said Jiacomo.

“You can go to Forpa or to some other place,” said the man, “but if you like adventure, I’d say you’re best off coming with me. I’ve only just met you, but you seem like a bright lad. Come and work with me, and I’ll teach you my trade. If you have a talent for it, you won’t regret it.”

“So what is your trade?” asked Jiacomo.

“Hmm,” said the man. “You could say that I’m a hunter. I hunt valuable game. My trade is one for skilful, intelligent and resourceful people. I’ll explain it to you in more detail later. Come with me. You’ll have a good life with me.”

40Jiacomo looked at him and decided that he seemed trustworthy. “Fine,” he said. “I’ll come with you.”

And so he went with the man, who turned out to be called Jannos, and they took it in turns to carry the sack.

After a while, Jannos and Jiacomo came to some big rocks.

“Here’s my house,” said Jannos.

Jiacomo looked surprised, as he couldn’t see anything resembling a house. But his companion gently pushed one of the rocks. It rolled aside and, after passing through a gap, they came to a small grassy area that was surrounded by more rocks. In the middle of the grass, there was a house made of stone, with two horses grazing beside it.

“Come inside,” said Jannos, “and make yourself at home. Now you’re my apprentice and your first duty is to tell no one where we live.”

41As soon as they were inside, he opened the sack and tipped its contents onto the floor. Jiacomo was astonished to see the valuable objects that came tumbling out: cups and bowls of beaten gold, silver coins, elegantly decorated daggers and glittering jewels. He wondered how Jannos, who did not look at all wealthy, had come by these precious items.

“Now I’m your apprentice,” he said. “But I still don’t know what I can learn from you.”

“You’ll find out soon enough,” replied Jannos. “Your lessons begin tomorrow.”

Then he put all of the objects into a large chest, which he carefully locked, and said: “We won’t talk about business now though. Go and sit at the table, and I’ll prepare a nice meal.”

Jiacomo was starving. So he did not ask any more questions, but tucked into the meal that Jannos had made.

That night in bed, he lay awake for a long time. He wondered what trade Jannos was going to teach him, as the man still refused to tell him anything. And he also thought about his brother. How was Laurenzo faring?

Laurenzo was back in Bainu, where Master Philippo was teaching him to be a goldsmith. He learnt how to forge and cast and beat metals, and he learnt how to tell the difference between different kinds of precious stones. He enjoyed his work, even though it would be some time before he could make beautiful objects, as Master Philippo could.

“How long will it take me to finish learning?” he once asked.

“You never finish learning,” replied the old goldsmith, “but in about three years or so you’ll be able to make some nice pieces. You have a talent for this work.”

42“But I can’t stay that long,” said Laurenzo. “I’m supposed to meet up with my brother after a year.”

“Then you can return to me after you’ve met up with him,” said the goldsmith. “No one can learn a trade in just a year.”

So Laurenzo sat in the workshop every day, surrounded by his animals. In addition to his dog, he now also had the two cats and two pigeons, which he had fetched from his old neighbours, with his master’s permission. One cat and one pigeon were for Jiacomo, when he came back to Bainu. Because Laurenzo was sure that would happen one day.

Meanwhile, Jiacomo had also begun his lessons. On the first day, Jannos gave him a bow and arrows and taught him how to shoot. He made a target close to his house, and Jiacomo practised for many hours. A week later, Jannos told him to get onto one of the horses and when the boy could ride, he took him out onto the plain and showed him every path, every rock and every hiding place.

So, when Jiacomo could both shoot and ride, and he knew his way around the area too, he asked his master when he would be able to go hunting.

“You don’t know enough yet,” said Jannos. “These were just the lessons 43to prepare you, which have little to do with the job itself, although they can come in handy. Now we’re really going to get started. Dexterity, that’s something you’ll need to develop. Remember, too, that the only reason you have weapons is so that you don’t have to use them – unless you’re really in trouble.”

Jiacomo did not understand what he meant, and he told him so.

“Wait and see,” said Jannos and he gave him a small box. “Open it,” he commanded.

“There’s no key,” said Jiacomo.

“That’s the point,” said his master. “Open this box without using a key.”

Jiacomo took a hammer, a pair of pliers and a nail, and he managed to force the lid.

“Not too bad for a first attempt,” said Jannos. “Now I’ll show you how to do it better – quickly and without making a sound.”

Within a few days, Jiacomo was opening all kinds of boxes and chests and doors, without using keys and without making any noise.

“Now for the next lesson,” said Jannos, when they were having dinner one night. “I want you to take the salt cellar from the table, without me seeing, and to drink my cup dry, without me noticing. You’ll need to be quick and skilful, and you’ll also have to spin a nice, entertaining yarn to distract me. No, if you reach out your hand like that, I’ll spot it straightaway.”

Jiacomo put down his spoon and said: “Tell me now what your trade is!”

44“Can’t you guess?” asked Jannos.

“I believe I can,” replied Jiacomo. “But if it’s true, then I can’t stay on as your apprentice.”

“Why not? It’s a fine job trade, with few true masters. Hey, where’s the salt cellar?”

“Here, in my hand,” said Jiacomo.

“Good work! You have talent,” said Jannos. “You know, you could become a decent robber and an excellent thief!”

A thief! That’s not an honest job, thought Jiacomo, and he said: “I’m sorry, master, but I don’t want to be a thief.”

“Don’t be so foolish,” said Jannos. “You’ve been training for a while now, and it would be a shame if you didn’t finish your studies. Stay at least until you have completed your final test. Then you’ll be fully skilled and qualified, so you’ll be able to make a living.”

Jiacomo had to admit that there was a lot of truth in his master’s words. Even if he never practised his trade, it might still prove useful. So he said: “Fine, I’ll stay,” and he picked up Jannos’s cup and downed his drink without him noticing.

“Laurenzo,” said Master Philippo to his apprentice, “I have to go to Forpa with two silver necklaces and a golden bowl that the duke has ordered from me. It’s springtime now and good weather for travelling, and I can go with an easy mind, as I know you and your dog will look after my house. Keep on working hard, even though I’m away.”

He said farewell to his apprentice, climbed onto his horse and went on his way, with the precious objects packed up carefully inside his saddlebag. In addition, he had armed 45himself with a dagger and a big stick, as he had to cross the Plain of Babina, where robbers sometimes roamed.

“Jiacomo,” said Jannos, the thief, to his apprentice, “now it is time for you to make practical use of your knowledge. We’ll start with something simple. It’s spring and travellers are using the road again. Your task today is to stop a man and rob him of his belongings. Make sure you come home with something good.”

Jiacomo hesitantly said that he was not too keen on the idea, but Jannos became angry and yelled: “Don’t be so foolish! What good is knowledge that you don’t use? You have to show that you’ve learnt my lessons well and prove that you can indeed carry out the trade of thievery. You’re not afraid, are you?”

Jiacomo was not afraid and besides he thought Jannos was right – well, looking at it from Jannos’s point of view anyway. Of course Jiacomo had to prove that he could rob and steal, even if his conscience was not entirely easy. So he armed himself, wrapped a piece of cloth around his face, so that only his eyes could be seen, climbed onto his horse and rode to the big road that went from Bainu to Forpa. When he got there, he hid behind a rocky outcrop and waited. His dog had followed him and jumped around him, barking. That would be sure to give him away, so he spoke sternly to the animal and told it to go home. It was not easy to make the dog obey, but finally it went and Jiacomo was alone.

He waited for a long time, but saw no living creatures except for the butterflies on the flowers and the lizards in the 46grass. Just as he was beginning to wonder if anyone would ever come, he heard the sound of hoofs. A little later, he saw a horse approaching, carrying an old man whose saddlebag looked nice and full. It was Master Philippo, but Jiacomo had no way of knowing that, of course. The young man waited until the traveller was close to him and then he stepped out from his hiding place. He drew his bow, nocked an arrow and shouted: “Your money or your life!”

Master Philippo urged on his horse and was about to flee, but Jiacomo blocked his path and repeated: “Your money or your life!”

The goldsmith raised his stick, but Jiacomo, much younger and stronger than him, pulled it from his hand and said: “Give me what you have and I won’t harm you.”

“You won’t harm me?” said the goldsmith, panting. “Robbing me? Is that what you call doing no harm? You can have what I am carrying, because you are stronger than me. But don’t pretend you’re doing me a favour by not killing me.”

Jiacomo did not reply, but started searching through his victim’s bag. He found the necklaces and the golden bowl – a valuable haul!

“So you have what you were looking for,” said the goldsmith. “Now clear off, you coward!”

“I’m no coward!” cried Jiacomo indignantly. “My job is a job like any other.”

“Then why are you hiding your face, as if you are ashamed? An honest man always dares to show who and what he is.”

Jiacomo was indeed ashamed. “Fine. You can see my face!” he cried. “Here you go!” And he pulled away the cloth.

47When the goldsmith saw his face, he almost fell off his horse. He stared incredulously at the young man. “Y-you!” he stammered.

Jiacomo, who had been about to ride off with his haul, stopped, surprised by the look on his victim’s face.

“You…” repeated the goldsmith. His surprise gave way to fury and disappointment. “You are robbing me!” he said. “Robbing me, when I have taught you and given you shelter, without ever asking for anything in return.”

“I don’t understand,” said Jiacomo.

“You two-faced liar!” cried the goldsmith. “I trusted you, Laurenzo, as I would have trusted my own son. I would never have believed you could behave like this!” Now Jiacomo understood.

“Laurenzo!” he cried. “You are mistaken. I am not Laurenzo.”

48“Silence!” said the goldsmith. “Just go! I never want to see you again.”

The old man was about to ride off, but Jiacomo stopped him.

“I’m truly not Laurenzo,” he said. “I’m Jiacomo, his twin brother.”

Master Philippo looked at him. Was this boy really not his apprentice? He remembered that Laurenzo had often spoken about his twin brother.

“Honestly,” Jiacomo persisted, “I’m not Laurenzo. Is he a friend of yours? Then please don’t think badly of him. Be angry with Jiacomo, not with his brother.”

The goldsmith believed him. “I’m glad you’re not Laurenzo,” he said. “Maybe I shouldn’t have suspected him, but how could I have known that he and his brother looked so alike?” He looked seriously at Jiacomo and added: “And I had no idea that Laurenzo’s brother was a robber!”

Jiacomo stared down at his feet. “Neither does Laurenzo,” he said. Then he looked back at the goldsmith and asked: “How is he?”

“Fine,” replied Master Philippo. “Better than you, or so it seems. He is my apprentice and he is learning to make the things you steal.”

Jiacomo blushed. Then he took out the silver necklaces and the golden bowl and put them in Master Philippo’s hands. “Here is your property,” he said. “I don’t want to rob a friend of Laurenzo’s. Give him my best wishes and tell him I’m longing for the moment when we will see each other again. And please also tell him that this is the first and last time I’ve ever stolen anything.”

49He turned his horse and galloped away, as quickly as he could. The goldsmith stared after him until he had disappeared from sight. 50

The twin brothers Laurenzo and Jiacomo lived far from each other and the work they did was very different. Laurenzo was an apprentice to Master Philippo, the goldsmith. He was going to become a goldsmith himself – and that was exactly what he wanted to do. Jiacomo had learnt how to rob and steal, but he no longer wished to become a thief. So he decided to leave his master, Jannos, and to learn an honest trade instead.

The Fourth Tale

The Silver Cups of Talamura

“I want to put you to the test and see what you can do.”

grimm: ‘The Four Skilful Brothers’

1 The Adventures Of Jiacomo

“So did you get something good?” Jannos the thief asked his apprentice, Jiacomo, upon his return from his first raid.

“Yes,” replied Jiacomo. “I stole two silver necklaces and a golden bowl.”

“Excellent,” said Jannos. “Let me see.”

“I can’t,” said Jiacomo. “I gave them back.”

“What did you say?” exclaimed Jannos.

“I gave them back,” repeated Jiacomo. “The man I robbed turned out to be a friend of my brother’s. He has taught him and given him a roof over his head. I can’t take something from a friend of my brother’s, can I?”

“You must be insane!” yelled Jannos. “You’re a terrible thief – that’s what you are!”

“I’ve proved that I can steal,” said Jiacomo, “and that was the point, wasn’t it? But I’m not going to steal any longer. I’m leaving.”

52“What? You’re leaving?” cried Jannos.

“Yes, I am,” replied Jiacomo. “I don’t want to be a thief.”

Jannos was furious, but neither cursing nor cajoling could sway Jiacomo from his decision.

“Now listen,” the thief said finally. “I’ve taught you and given you a roof over your head, without ever asking for anything in return. It would be most ungrateful if you left me just like that.”

These words got through to Jiacomo and, spotting this weakness, the clever Jannos continued: “So let’s come to an agreement. You will carry out a job for me. When you have done that, your debt to me will be paid and you will also have proved your mastery.”

Jiacomo really did not want to steal again, but he could not help asking: “So what’s this job?”

“In the west, among the rocks and the pine forests that border the plain, lies the Castle of Talamura. A rich and powerful man lives there, who owns many treasures. Among those treasures are thirteen silver cups, beautiful and precious, decorated with magnificent engravings. I have always planned to steal those cups, although the Lord of Talamura knows me and has sworn that he will hang me. This is my task for you: bring me one of those cups. It only needs to be one. If you succeed, your debt to me is paid, and you can call yourself my equal, a master thief.”

Jiacomo thought about it. The job was tempting, but he had made up his mind never to steal again.

“Oh dear,” said Jannos, shaking his head. “I can already see it on your face. You won’t do it. The task’s too difficult. You’re too scared to accept my challenge.”

53“Of course I’m not!” cried Jiacomo. “It’s just that I don’t want to be a thief.”

“Well, maybe you’re not scared,” said Jannos, “but you’re simply not up to it. Only a master thief could steal one of the silver cups of Talamura.”

“Didn’t you train me well enough?” asked Jiacomo.

“I certainly did,” said Jannos, “but this is all down to you and to your own ingenuity, and I can’t give you that, not in a thousand lessons.”

“Tell me more about these cups,” said Jiacomo.

“I’ve already told you they’re made of silver,” replied Jannos, “decorated with beautiful engravings and with the arms of Talamura on them: an eagle and a squirrel on either side of a pine tree. The Lord of Talamura is very fond of them and keeps them closely guarded against thieves. They are said to stand next to each other on a shelf inside a large cabinet, but there are of course many cupboards in the castle, so I cannot tell you exactly where they are kept.”

“What’s the castle like?”

“Strong and impregnable. It’s up on top of a rock. Day and night, there are guards at the gate, and no stranger is admitted.”

“Are there any secret doors? Or hidden passageways? Or weak spots in the walls?”

“The walls are many feet thick, and there are no secret passages.”

“So how am I ever supposed to get inside?” asked Jiacomo. “How am I going to steal one of the cups?”

“I don’t care,” replied Jannos. “I asked you for a cup, and I’m not interested in how you get it. But let’s not talk about 54this any longer. You don’t want to steal anyway, and I can see that this task is too difficult for you.”

“It is hard, I will admit that,” said Jiacomo. “But not so hard that I won’t give it a try.”

“I’ll just come up with another task for you,” said Jannos.

“No,” said Jiacomo, “this one suits me fine.”

“So you’ll do it?” asked Jannos.

“Yes,” replied Jiacomo. He might not have wanted to steal any longer, but the lure of the adventure and the challenge was too strong for him. If the Lord of Talamura owned thirteen cups, then surely he could do without one of them. Besides, Jiacomo thought he should do something for Jannos, who had done so much for him, without ever asking for payment.

The thief smiled at him. “You are a boy after my own heart,” he said. “And I wish you good luck. This is a true test of mastery, which is first and foremost about cleverness. Go and have a look inside my chests – you’ll find everything you need, from false beards to crowbars.”

Jiacomo picked out everything that he wanted to take and the next morning he dressed himself in the finest clothes he could find. He buckled a sword around his waist and on his feet he wore leather boots with silver spurs.