1,90 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lebooks Editora

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

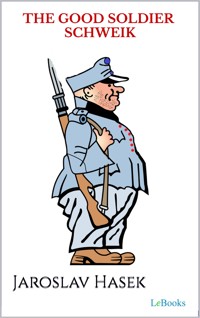

The Good Soldier Schweik is a satirical masterpiece that exposes the absurdities of war, bureaucracy, and blind obedience through the misadventures of its protagonist, Josef Švejk. Written by Jaroslav Hašek, the novel follows Schweik, a seemingly simple-minded yet cunningly subversive soldier, as he navigates the chaos of World War I. With sharp irony and dark humor, Hašek critiques the incompetence of military institutions and the hypocrisy of authority figures, portraying a world in which survival often depends on feigned ignorance and strategic foolishness. Since its publication, The Good Soldier Schweik has been celebrated for its biting wit, satirical depth, and its unique protagonist, whose apparent naivety serves as a powerful tool for exposing the contradictions of rigid hierarchies. Its exploration of the absurdity of war and the resilience of the individual against oppressive systems has cemented its place as a seminal work of anti-war literature. The novel's episodic structure and richly drawn characters continue to captivate readers, offering both comic relief and sharp social commentary. The book's enduring relevance lies in its ability to highlight the paradoxes of authority and the unpredictability of human nature in times of conflict. By blending humor with critique,The Good Soldier Schweik challenges readers to reconsider notions of duty, resistance, and the true cost of blind loyalty in a world governed by irrational rules and senseless violence.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 411

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Jaroslav Hašek

THE GOOD SOLDIER SCHWEIK

Original Title:

“Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka za světové války”

Contents

INTRODUCTION

THE GOOD SOLDIER SCHWEIK

BOOK I

BOOK II

BOOK III

INTRODUCTION

Jaroslav Hašek

1883 – 1923

Jaroslav Hašek was a Czech writer, journalist, and satirist, best known for his novel "The Good Soldier Švejk." Born in Prague, in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Hašek gained renown for his biting satire and humorous critique of authority, bureaucracy, and the absurdities of war. His work, particularly "The Good Soldier Švejk," remains a seminal piece in anti-war literature and has influenced generations of writers and political thinkers.

Early Life and Education

Jaroslav Hašek was born into a modest family and lost his father at a young age. Despite financial difficulties, he attended the Czech Higher Grade School and later the Prague Business Academy, where he studied commerce. However, he quickly abandoned a conventional career path in favor of literature and journalism. Hašek lived an unconventional and often chaotic life, traveling extensively, engaging in political activism, and writing for satirical magazines.

Career and Contributions

Hašek wrote thousands of short stories, sketches, and satirical pieces, often lampooning the inefficiencies of bureaucracy and the hypocrisies of society. However, his most significant contribution to literature is "The Good Soldier Švejk," a novel published in installments starting in 1921 and left unfinished at his death in 1923. The book follows the misadventures of Josef Švejk, a seemingly simple-minded but cunning soldier navigating the absurdities of World War I. Through humor, irony, and absurdity, Hašek exposes the incompetence and futility of military and governmental institutions.

Impact and Legacy

Hašek's work was groundbreaking in its time, blending satire, political criticism, and dark humor to challenge the established norms. "The Good Soldier Švejk" has been translated into numerous languages and adapted into various forms, including theater and film. His depiction of war as a senseless bureaucratic farce resonated deeply with readers and influenced later anti-war literature, including the works of Kurt Vonnegut and Joseph Heller.

Jaroslav Hašek died at the age of 39 in 1923, suffering from health complications exacerbated by his erratic lifestyle. Although he did not live to see the full impact of his work, "The Good Soldier Švejk" remains one of the most important satirical novels of all time. His legacy endures in literature and popular culture, serving as a testament to the power of humor and satire in exposing societal absurdities and injustices. Hašek's sharp wit and irreverent storytelling continue to captivate readers, ensuring his place among the great literary satirists of the 20th century.

About the work

The Good Soldier Schweik is a satirical masterpiece that exposes the absurdities of war, bureaucracy, and blind obedience through the misadventures of its protagonist, Josef Švejk. Written by Jaroslav Hašek, the novel follows Schweik, a seemingly simple-minded yet cunningly subversive soldier, as he navigates the chaos of World War I. With sharp irony and dark humor, Hašek critiques the incompetence of military institutions and the hypocrisy of authority figures, portraying a world in which survival often depends on feigned ignorance and strategic foolishness.

Since its publication, The Good Soldier Schweik has been celebrated for its biting wit, satirical depth, and its unique protagonist, whose apparent naivety serves as a powerful tool for exposing the contradictions of rigid hierarchies. Its exploration of the absurdity of war and the resilience of the individual against oppressive systems has cemented its place as a seminal work of anti-war literature. The novel’s episodic structure and richly drawn characters continue to captivate readers, offering both comic relief and sharp social commentary.

The book’s enduring relevance lies in its ability to highlight the paradoxes of authority and the unpredictability of human nature in times of conflict. By blending humor with critique,The Good Soldier Schweik challenges readers to reconsider notions of duty, resistance, and the true cost of blind loyalty in a world governed by irrational rules and senseless violence.

THE GOOD SOLDIER SCHWEIK

A great epoch calls for great men. There are modest unrecognized heroes, without Napoleon’s glory or his record of achievements. An analysis of their characters would overshadow even the glory of Alexander the Great. To-day, in the streets of Prague, you can come across a man who himself does not realize what his significance is in the history of the great new epoch. Modestly he goes his way, troubling nobody, nor is he himself troubled by journalists applying to him for an interview. If you were to ask him his name, he would answer in a simple and modest tone of voice: “I am Schweik.”

And this quiet, unassuming, shabbily dressed man is actually the good old soldier Schweik; that heroic, dauntless man who was the talk of all citizens in the Kingdom of Bohemia when they were under Austrian rule, and whose glory will not pass away even now that we have a Republic.

I am very fond of the good soldier Schweik, and in presenting an account of his adventures during the Great War, I am convinced that you will all sympathize with this modest, unrecognized hero. He did not set fire to the temple of the goddess at Ephesus, like that fool of a Herostratus, merely in order to get his name into the newspapers and the school reading books.

And that, in itself, is enough.

THEGOOD SOLDIER SCHWEIK

BOOK I

CHAPTER I – SCHWEIK, THE GOOD SOLDIER, INTERVENES IN THE GREAT WAR

“So they’ve killed Ferdinand,” said the charwoman to Mr. Schweik who, having left the army many years before, when a military medical board had declared him to be chronically feeble-minded, earned a livelihood by the sale of dogs — repulsive mongrel monstrosities for whom he forged pedigrees. Apart from this occupation, he was afflicted with rheumatism, and was just rubbing his knees with embrocation.

“Which Ferdinand, Mrs. Muller?” asked Schweik, continuing to massage his knees. “I know two Ferdinands. One of them does jobs for Prusa the chemist, and one day he drank a bottle of hair oil by mistake;

and then there’s Ferdinand Kokoska who goes round collecting manure. They wouldn’t be any great loss, either of ’em.”

“No, it’s the Archduke Ferdinand, the one from Konopiste, you know, Mr. Schweik, the fat, pious one.”

“Good Lord!” exclaimed Schweik, “that’s a fine thing. And where did this happen?”

“They shot him at Sarajevo with a revolver, you know. He was riding there with his Archduchess in a motor car.”

“Just fancy that now, Mrs. Muller, in a motor car. Ah, a gentleman like him can afford it and he never thinks how a ride in a motor car like that can end up badly. And at Sarajevo in the bargain, that’s in Bosnia, Mrs. Muller. I expect the Turks did it. I reckon we never ought to have taken Bosnia and Herzegovina away from them. And there you are, Mrs. Muller. Now the Archduke’s in a better land. Did he suffer long?”

“The Archduke was done for on the spot. You know, people didn’t ought to mess about with revolvers. They’re dangerous things, that they are. Not long ago there was another gentleman down our way larking about with a revolver and he shot a whole family as well as the house porter, who went to see who was shooting on the third floor.”

“There’s some revolvers, Mrs. Muller, that won’t go off, even if you tried till you was dotty. There’s lots like that. But they’re sure to have bought something better than that for the Archduke, and J wouldn’t mind betting, Mrs. Muller, that the man who did it put on his best clothes for the job. You know, it wants a bit of doing to shoot an archduke; it’s not like when a poacher shoots a gamekeeper. You have to find out how to get at him; you can’t reach an important man like that if you’re dressed just anyhow. You have to wear a top hat or else the police’d run you in before you knew where you were.”

“I hear there was a whole lot of ’em, Mr. Schweik.”

“Why, of course there was, Mrs. Muller,” said Schweik, now concluding the massage of his knees. “If you wanted to kill an archduke or the Emperor, for instance, you’d naturally talk it over with somebody. Two heads are better than one. One gives one bit of advice, another gives another, and so the good work prospers, as the hymn says. The chief thing is to keep on the watch till the gentleman you’re after rides past.... But there’s plenty more of them waiting their turn for it. You mark my words, Mrs. Muller, they’ll get the Czar and Czarina yet, and maybe, though let’s hope not, the Emperor himself, now that they’ve started with his uncle. The old chap’s got a lot of enemies. More than Ferdinand had. A little while ago a gentleman in the saloon bar was saying that there’d come a time when all the emperors would get done in one after another, and that not all their bigwigs and such-like would save them.”

“The newspaper says, Mr. Schweik, that the Archduke was riddled with bullets. He emptied the whole lot into him.”

“That was mighty quick work, Mrs. Muller, mighty quick. I’d buy a Browning for a job like that. It looks like a toy, but in a couple of minutes you could shoot twenty archdukes with it, thin or fat. Although between ourselves, Mrs. Muller, it’s easier to hit a fat archduke than a thin one. You may remember the time they shot their king in Portugal. He was a fat fellow. Of course, you don’t expect a king to be thin. Well, now I’m going to call round at The Flagon and if anybody comes for that little terrier I took the advance for, you can tell ’em I’ve got him at my dog farm in the country. I just cropped his ears and now he mustn’t be taken away till his ears heal up or else he’d catch cold in them. Give the key to the house porter.”

There was only one customer at The Flagon. This was Bretschneider, a plainclothes policeman who was on secret service work. Palivec, the landlord, was washing glasses and Bretschneider vainly endeavoured to engage him in a serious conversation.

“We’re having a fine summer,” was Bretschneider’s overture to a serious conversation.

“Damn rotten,” replied Palivec, putting the glasses away into a cupboard.

“That’s a fine thing they’ve done for us at Sarajevo,” Bretschneider observed, with his hopes rather dashed.

“I never shove my nose into that sort of thing, I’m hanged if I do,” primly replied Mr. Palivec, lighting his pipe. “Nowadays, it’s as much as your life’s worth to get mixed up in them. I’ve got my business to see to. When a customer comes in and orders beer, why I just serve him his drink. But Sarajevo or politics or a dead archduke, that’s not for the likes of us, unless we want to end up doing time.”

Bretschneider said no more, but stared disappointedly round the empty bar.

“You used to have a picture of the Emperor hanging here,” he began again presently, “just at the place where you’ve got a mirror now.”

“Yes, that’s right,” replied Mr. Palivec, “it used to hang there and the flies left their trade-mark on it, so I put it away into the lumber room. You see, somebody might pass a remark about it and then there might be trouble. What use is it to me?”

“That business at Sarajevo,” Bretschneider resumed, “was done by the Serbs.”

“You’re wrong there,” replied Schweik, “it was done by the Turks, because of Bosnia and Herzegovina.”

And Schweik expounded his views of Austrian international policy in the Balkans. The Turks were the losers in 1912 against Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece. They had wanted Austria to help them and when this was not done, they had shot Ferdinand.

“Do you like the Turks?” said Schweik, turning to Palivec. “Do you like that heathen pack of dogs? You don’t, do you?”

“One customer’s the same as another customer,” said Palivec, “ even if he’s a Turk. People like us who’ve got their business to look after can’t be bothered with politics. Pay for your drink and sit down and say what you like. That’s my principle. It’s all the same to me whether our Ferdinand was done in by a Serb or a Turk, a Catholic or a Moslem, an Anarchist or a young Czech Liberal.”

“That’s all well and good, Mr. Palivec,” remarked Bretschneider, who had regained hope that one or other of these two could be caught out, “ but you’ll admit that it’s a great loss to Austria.”

Schweik replied for the landlord:

“Yes, there’s no denying it. A shocking loss. You can’t replace Ferdinand by any sort of tomfool. If war was to break out to-day, I’d go of my own accord and serve the Emperor to my last breath.”

Schweik took a deep gulp and continued:

“Do you think the Emperor’s going to put up with that sort of thing? Little do you know him. You mark my words, there’s got to be war with the Turks. Kill my uncle, would you? Then take this smack in the jaw for a start. Oh, there’s bound to be war. Serbia and Russia’U help us. There won’t half be a bust-up.”

At this prophetic moment Schweik was really good to look upon. His artless countenance, smiling like the full moon, beamed with enthusiasm. The whole thing was so utterly clear to him.

“Maybe,” he continued his delineation of the future of Austria, “if we have war with the Turks, the Gerrnans’U attack us, because the Germans and the Turks stand by each other. They’re a low lot, the scum of the earth. Still, we can join France, because they’ve had a grudge against Germany ever since *. And then there’ll be lively doings. There’s going to be war. I can’t tell you more than that.”

Bretschneider stood up and said solemnly:

“You needn’t say any more. Follow me into the passage and there I’ll say something to you.”

Schweik followed the plainclothes policeman into the passage where a slight surprise awaited him when his fellow-toper showed him his badge and announced that he was now arresting him and would at once convey him to the police headquarters. Schweik endeavoured to explain that there must be some mistake; that he was entirely innocent; that he hadn’t uttered a single word capable of offending anyone.

But Bretschneider told him that he had actually committed several penal offences, among them being high treason.

Then they returned to the saloon bar and Schweik said to Mr. Palivec:

“I’ve had five beers and a couple of sausages with a roll. Now let me have a cherry brandy and I must be off, as I’m arrested.”

Bretschneider showed Mr. Palivec his badge, looked at Mr. Palivec for a moment and then asked:

“Are you married?”

“Yes.”

“And can your wife carry on the business during your absence?”

“Yes.”

“That’s all right, then, Mr. Palivec,” said Bretschneider breezily. “Tell your wife to step this way; hand the busi-ness over to'her, and we’ll come for you in the evening.”

“Don’t you worry about that,” Schweik comforted him. “I’m only being run in for high treason.”

“But what about me?” lamented Mr. Palivec. “I’ve been so careful what I said.”

Bretschneider smiled and said triumphantly:

“I’ve got you for saying that the flies left their trademark on the Emperor. You’ll have all that stuff knocked out of your head.”

And Schweik left The Flagon in the company of the plainclothes policeman.

And thus Schweik, the good soldier, intervened in the Great War in that pleasant, amiable manner which was so peculiarly his. It will be of interest to historians to know that he saw far into the future. If the situation subsequently developed otherwise than he expounded it at The Flagon, we must take into account the fact that he lacked a preliminary diplomatic training.

CHAPTER II – SCHWEIK, THE GOOD SOLDIER, AT THE POLICE HEADQUARTERS

The Sarajevo assassination had filled the police headquarters with numerous victims. They were brought in, one after the other, and the old inspector in the reception bureau said in his good-humoured voice: “This Ferdinand business is going to cost you dear.” When they had shut Schweik up in one of the numerous dens on the first floor, he found six persons already assembled there. Five of them were sitting round the table, and in a corner a middle-aged man was sitting on a mattress as if he were holding aloof from the rest.

Schweik began to ask one after the other why they had been arrested.

From the five sitting at the table he received practically the same reply:

“That Sarajevo business.” “That Ferdinand business.” “It’s all through that murder of the Archduke.” “That Ferdinand affair.” “Because they did the Archduke in at Sarajevo.”

The sixth man who was holding aloof from the other five said that he didn’t want to have anything to do with them because he didn’t want any suspicion to fall on him. He was there only for attempted robbery with violence.

Schweik joined the company of conspirators at the table, who were telling each other for at least the tenth time how they had got there.

All, except one, had been caught either in a public house, a wineshop or a caf6. The exception consisted of an extremely fat gentleman with spectacles and tear-stained eyes who had been arrested in his own home because two days before the Sarajevo outrage he had stood drinks to two Serbian students, and had been observed by Detective Brix drunk in their company at the Montmartre night club where, as he had already confirmed by his signature in the report, he had again stood them drinks.

When Schweik had heard all these dreadful tales of conspiracy he thought fit to make clear to them the complete hopelessness of their situation.

“We’re all in the deuce of a mess,” he began his words of comfort. “You say that nothing can happen to you, or to any of us, but you’re wrong. What have we got the police for except to punish us for letting our tongues wag? If the times are so dangerous that archdukes get shot, the likes of us mustn’t be surprised if we’re taken up before the beak. They’re doing all this to make a bit of a splash, so that Ferdinand’ll be in the limelight before his funeral. The more of us there are, the better it’ll be for us, because we’ll feel all the jollier.”

Whereupon Schweik stretched himself out on the mattress and fell asleep contentedly.

In the meanwhile, two new arrivals were brought in.

One of them was a Bosnian. He walked up and down gnashing his teeth. The other new guest was Palivec who, on seeing his acquaintance Schweik, woke him up and exclaimed in a voice full of tragedy:

“Now I’m here, too!”

Schweik shook hands with him cordially and said :

“ I’m glad of that, really I am. I felt sure that gentle-man’d keep his word when he told you they’d come and fetch you. It’s nice to know you can rely on people.”

Mr. Palivec, however, remarked that he didn’t care a damn whether he could rely on people or not, and he asked Schweik on the quiet whether the other prisoners were thieves who might do harm to his business reputation.

Schweik explained to him that all except one, who had been arrested for attempted robbery with violence, were there on account of the Archduke.

Schweik went back to sleep, but not for long, because they soon came to take him away to be cross-examined.

And so, mounting the staircase to Section 3 for his cross-examination, and beaming with good nature, he entered the bureau, saying:

“Good evening, gentlemen, I hope you’re all well.”

Instead of a reply, someone pummelled him in the ribs and stood him in front of a table, behind which sat a gentleman with a cold official face and features of such brutish savagery that he looked as if he had just tumbled out of Lombroso’s book on criminal types.

He hurled a bloodthirsty glance at Schweik and said:

“Take that idiotic expression off your face.”

“I can’t help it,” replied Schweik solemnly. “I was discharged from the army on account of being weak-minded and a special board reported me officially as weak-minded. I’m officially weak-minded — a chronic case.”

The gentleman with the criminal countenance grated his teeth as he said:

“The offence you’re accused of and that you’ve committed shows you’ve got all your wits about you.”

And he now proceeded to enumerate to Schweik a long list of crimes, beginning with high treason and ending with insulting language toward His Royal Highness and members of the Royal Family. The central gem of this collection constituted approval of the murder of the Archduke Ferdinand, and from this again branched off a string of fresh offences, amongst which sparkled incitement to rebellion, as the whole business had happened in a public place.

“What have you got to say for yourself?” triumphantly asked the gentleman with the features of brutish savagery.

“There’s a lot of it,” replied Schweik innocently. “You can have too much of a good thing.”

“So you admit it’s true?”

“I admit everything. You’ve got to be strict. If you ain't strict, why, where would you be? It’s like when I was in the army----”

“Hold your tongue!” shouted the police commissioner. “And don’t say a word unless you’re asked a question. Do you understand?”

“Begging your pardon, sir, I do, and I’ve properly got the hang of every word you utter.”

“Who do you keep company with?”

“The charwoman, sir.”

“And you don’t know anybody in political circles here?”

“Yes, sir, I take in the afternoon edition of the Narodni Politika, you know, sir, the paper they call the puppy’s delight.”

“Get out of here!” roared the gentleman with the brutish appearance.

When they were taking him out of the bureau, Schweik said:

“Good night, sir.”

Having been deposited in lais cell again, Schweik informed all the prisoners that the cross-examination was great fun. “They yell at you a bit and then kick you out.” He paused a moment. “In olden times,” continued Schweik, “it used to be much worse. I once read a book where it said that people charged with anything had to walk on red-hot iron and drink molten lead to see whether they was innocent or not. There was lots who was treated like that and then on top of it all they was quartered or put in the pillory somewhere near the Natural History Museum.”

“Nowadays, it’s great fun being run in,” continued Schweik with relish. “There’s no quartering or anything of that kind. We’ve got a mattress, we’ve got a table, we’ve got a seat, we ain’t packed together like sardines, we’ll get soup, they’ll give us bread, they’ll bring a pitcher of water, there’s a closet right under our noses. It all shows you what progress there’s been. Ah, yes, nowadays things have improved for our benefit.”

He had just concluded his vindication of the modern imprisonment of citizens when the warder opened the door and shouted:

“ Schweik, you’ve got to get dressed and go to be cross-examined.”

Schweik again stood in the presence of the criminal faced gentleman who, without any preliminaries, asked him in a harsh and relentless tone:

“Do you admit everything?”

Schweik fixed his kindly blue eyes upon the pitiless person and said mildly:

“If you want me to admit it, sir, then I will. It can’t do me any harm.”

The severe gentleman wrote something on his documents and, handing Schweik a pen, told him to sign.

And Schweik signed Bretschneider’s depositions, with the following addition:

All the above-mentioned accusations against me are based upon truth.

Josef Schweik.

When he had signed, he turned to the severe gentleman!

“Is there anything else for me to sign? Or am I to come back in the morning?”

“You’ll be taken to the criminal court in the morning,” was the answer.

“What time, sir? You see, I wouldn’t like to oversleep myself, whatever happens.”

“ Get out! ” came a roar for the second time that day from the other side of the table before which Schweik had stood.

As soon as the door had closed behind him, his fellow-prisoners overwhelmed him with all sorts of questions, to which Schweik replied brightly:

“I’ve just admitted I probably murdered the Archduke Ferdinand.”

And as he lay down on the mattress, he said:

“It’s a pity we haven’t got an alarm clock here.”

But in the morning they woke him up without an alarm clock, and precisely at six Schweik was taken away in the Black Maria to the county criminal court.

“The early bird catches the worm,” said Schweik to his fellow-travelers, as the Black Maria was passing out through the gates of the police headquarters.

CHAPTER III – SCHWEIK BEFORE THE MEDICAL AUTHORITIES

The clean, cosy cubicles of the county criminal court produced a very favourable impression upon Schweik. And the examining justices, the Pilates of the new epoch, instead of honourably washing their hands, sent out for stew and Pilsen beer, and kept on transmitting new charges to the public prosecutor.

It was to one of these gentlemen that Schweik was conducted for cross-examination. When Schweik was led before him, he asked him with his inborn courtesy to sit down, and then said:

“So you’re this Mr. Schweik?”

“I think I must be,” replied Schweik, “because my dad was called Schweik and my mother was Mrs. Schweik. I couldn’t disgrace them by denying my name.”

A bland smile flitted across the face of the examining counsel.

“This is a fine business you’ve been up to. You’ve got plenty on your conscience.”

“I’ve always got plenty on my conscience,” said Schweik, smiling even more blandly than the counsel himself. “ I bet I’ve got more on my conscience than what you have, sir.”

“I can see that from the statement you signed,” said the legal dignitary, in the same kindly tone. “ Did they bring any pressure to bear upon you at the police headquarters?”

“Not a bit of it, sir. I myself asked them whether I had to sign it and when they said I had to, why, I just did what they told me. It’s not likely that I’m going to quarrel with them over my own signature. I shouldn’t be doing myself any good that way. Things have got to be done in proper order.”

“Do you feel quite well, Mr. Schweik?”

“I wouldn’t say quite well, your worship. I’ve got rheumatism and I’m using embrocation for it.”

The old gentleman again gave a kindly smile. “ Suppose we were to have you examined by the medical authorities.”

“I don’t think there’s much the matter with me and it wouldn’t be fair to waste the gentlemen’s time. There was one doctor examined me at the police headquarters.”

“All the same, Mr. Schweik, we’ll have a try with the medical authorities. We’ll appoint a little commission, we’ll have you placed under observation, and in the meanwhile you’ll have a nice rest. Just one more question : According to the statement you’re supposed to have said that now a war’s going to break out soon.”

“Yes, your worship, it’ll break out at any moment now.”

That concluded the cross-examination. Schweik shook hands with the legal dignitary, and on his return to the cell he said to his neighbors:

“Now they’re going to have me examined by the medical authorities on account of this murder of Archduke Ferdinand.”

“I don’t trust the medical authorities,” remarked a man of intelligent appearance. “Once when I forged some bills of exchange I went to a lecture by Dr. Heveroch, and when they nabbed me I pretended to have an epileptic fit, just like Dr. Heveroch described it. I bit the leg of one of the medical authorities on the commission and drank the ink out of the inkpot. But just because I bit a man in the calf they reported I was quite well, and so I was done for.”

“I think,” said, Schweik, “that we ought to look at everything fair and square. Anybody can make a mistake, and the more he thinks about a thing, the more mistakes he’s bound to make. Why, even cabinet ministers can make mistakes.”

The commission of medical authorities which had to decide whether Schweik’s standard of intelligence did, or did not, conform to all the crimes with which he was charged, consisted of three extremely serious gentlemen with views which were such that the view of each separate one of them differed considerably from the views of the other two.

They represented three distinct schools of thought with regard to mental disorders.

If in the case of Schweik a complete agreement was reached between these diametrically opposed scientific camps, this can be explained simply and solely by the overwhelming impression produced upon them by Schweik who, on entering the room where his state of mind was to be examined and observing a picture of the Austrian ruler hanging on the wall, shouted: “Gentlemen, long live our Emperor, Franz Josef the First.”

The matter was completely clear. Schweik’s spontaneous utterance made it unnecessary to ask a whole’ lot of questions, and there remained only some of the most important ones, the answers to which were to corroborate Schweik’s real opinion, thus:

“Is radium heavier than lead?”

“I’ve never weighed it, sir,” answered Schweik with his sweet smile.

“Do you believe in the end of the world?”

“I’d have to see the end of the world first,” replied Schweik in an offhand manner, “but I’m sure it won’t come my way to-morrow.”

“Could you measure the diameter of the globe?”

“No, that I couldn’t, sir,” answered Schweik, “but now I’ll ask you a riddle, gentlemen. There’s a threestoried house with eight windows on each story. On the roof there are two gables and two chimneys. There are two tenants on each story. And now, gentlemen, I want you to tell me in what year the house porter’s grandmother died?”

The medical authorities looked at each other meaningly, but nevertheless one of them asked one more question:

“Do you know the maximum depth of the Pacific Ocean?”

“ I’m afraid I don’t, sir,” was the answer, “ but it’s pretty sure to be deeper than what the river is just below Prague.”

The chairman of the commission curtly asked: “Is that enough?” But one member inquired further:

“How much is 12897 times 13863?”

“729,” answered Schweik without moving an eyelash.

“I think that’s quite enough,” said the chairman of the commission. “You can take this prisoner back to where he came from.”

“Thank you, gentlemen,” said Schweik respectfully, “it’s quite enough for me, too.”

After his departure the three experts agreed that Schweik was an obvious imbecile in accordance with all the natural laws discovered by mental specialists.

CHAPTER IV – SCHWEIK IS EJECTED FROM THE LUNATIC ASYLUM

When Schweik later on described life in the lunatic asylum, he did so in terms of exceptional eulogy: “The life there was a fair treat. You can bawl, or yelp, oj sing, or blub, or moo, or boo, or jump, say your prayers or turn somersaults, or walk on all fours, or hop about on one foot, or run round in a circle, or dance, or skip, or squat on your haunches all day long, and climb up the walls. I liked being in the asylum, I can tell you, and while I was there I had the time of my life.”

And, in good sooth, the mere welcome which awaited Schweik in the asylum, when they took him there from the central criminal court for observation, far exceeded anything he had expected. First of all they took him to have a bath. In the bathroom they immersed him in a tub of warm water and then pulled him out and placed him under a cold douche. They repeated this three times and then asked him whether he liked it. Schweik said that it was better than the public baths near the Charles Bridge and that he was very fond of bathing. “If you’ll only just clip my nails and hair. I’ll be as happy as can be,” he added, smiling affably.

They complied with this request, and when they had thoroughly rubbed him down with a sponge, they wrapped him up in a sheet and carried him off into ward No. 1 to bed, where they laid him down, covered him over with a quilt, and told him to go to sleep.

And so he blissfully fell asleep on the bed. Then they woke him up to give him a basin of milk and a roll. The roll was already cut up into little pieces and while one of the keepers held Schweik’s hands, the other dipped the bits of roll into milk and fed him as poultry is fed with clots of dough for fattening. After he had gone to sleep again, they woke him up and took him to the observation ward where Schweik, standing stark naked before. two doctors, was reminded of the glorious time when he joined the army.

“Take five paces forward and five paces to the rear,” remarked one of the doctors.

Schweik took ten paces.

“I told you,” said the doctor, “to take five.”

“A few paces more or less don’t matter to me,” said Schweik.

Thereupon the doctors ordered him to sit on a chair and one of them tapped him on the knee. He then told the other one that the reflexes were quite normal, whereat the other wagged his head and he in his turn began to tap Schweik on the knee, while the first one lifted Schweik’s eyelids and examined his pupils. Then they went off to a table and bandied some Latin phrases.

One of them asked Schweik:

“Has the state of your mind ever been examined?”

“In the army,” replied Schweik solemnly and proudly, “the military doctors officially reported me as feebleminded.”

“It strikes me that you’re a malingerer,” shouted one of the doctors.

“Me, gentlemen?” said Schweik deprecatingly. “No, I’m no malingerer, I’m feeble-minded, fair and square. You ask them in the orderly room of the 91st regiment or at the reserve headquarters in Karlin.”

The elder of the two doctors waved his hand with a gesture of despair and pointing to Schweik said to the keepers: “Let this man have his clothes again and put him into Section 3 in the first passage. Then one of you can come back and take all his papers into the office. And tell them there to settle it quickly, because we don’t want to have him on our hands for long.”

The doctors cast another crushing glance at Schweik, who deferentially retreated backward to the door, bowing with unction all the while. From the moment when the keepers received orders to return Schweik’s clothes to him, they no longer showed the slightest concern for him. They told him to get dressed, and one of them took him to Ward No. 3 where, for the few days it took to complete his written ejection in the office, he had an opportunity of carrying on his agreeable observations. The disappointed doctors reported that he was “a malingerer of weak intellect,” and as they discharged him before lunch, it caused quite a little scene. Schweik declared that a man cannot be ejected from a lunatic asylum without having been given liis lunch first. This disorderly behaviour was stopped by a police officer who had been summoned by the asylum porter and who conveyed Schweik to the commissariat of police.

CHAPTER V – SCHWEIK AT THE COMMISSARIAT OF POLICE

Schweik’s bright sunny days in the asylum were followed by hours laden with persecution. Police Inspector Braun, as brutally as if he were a Roman hangman during the delightful reign of Nero, said: “Shove him in clink.”

Not a word more or less. But as he said it, the eyes of Inspector Braun shone with a strange and perverse joy.

In the cell a man was sitting on a bench, deep in meditation. He sat there listlessly, and from his appearance it was obvious that when the key grated in the lock of the cell he did not imagine this to be the token of approaching liberty.

“ Good-day to you, sir,” said Schweik, sitting down by his side on the bench. “I wonder what time it can be?”

The solemn man did not reply. He stood up and began to walk to and fro in the tiny space between door and bench, as if he were in a hurry to save something.

Schweik meanwhile inspected with interest the inscriptions daubed upon the walls. There was one inscription in which an anonymous prisoner had vowed a life-and-death struggle with the police. The wording was : “ You won’t half cop it.” Another had written: “ Rats to you, fatheads.” Another merely recorded a plain fact: “I was locked up here on June 5, 1913, and got fair treatment.” Next to this some poetic soul had inscribed the verse:

I sit in sorrow by the stream.

The sun is hid behind the hill.

I watch the uplands as they gleam, Where my beloved tarries still.

The man who was now running to and fro between door and bench came to a standstill, and sat down breathless in his old place, sank his head in his hands and suddenly shouted:

“Let me out!”

Then, talking to himself: “No, they won’t let me out, they won’t, they won’t. I’ve been here since six o’clock this morning.”

He then became unexpectedly communicative. He rose up and inquired of Schweik:

“You don’t happen to have a strap on you so that I could end it all?”

“Pleased to oblige,” answered Schweik, undoing his strap. “I’ve never seen a man hang himself with a strap in a cell.”

“It’s a nuisance, though,” he continued, looking round about, “that there isn’t a hook here. The bolt by the window wouldn’t hold you. I tell you what you might do, though. You could kneel down by the bench and hang yourself that way. I’m very keen on suicides.”

The gloomy man into whose hands Schweik had thrust the strap looked at it, threw it into a corner and burst out crying, wiping away his tears with his grimy hands and yelling the while. “I’ve got children! Heavens above, my poor wife! What will they say at the office? I’ve got children! ” and so ad infinitum.

At last, however, he calmed down a little, went to the door and began to thump and beat at it with his fist. From behind the door could be heard steps and a voice:

“What do you want?”

“Let me out,” he said in a voice which sounded as if he had nothing left to live for.

“Where to?” was the answer from the other side.

“To my office,” replied the unhappy father.

Amid the stillness of the corridor could be heard laughter, dreadful laughter, and the steps moved away again.

“It looks to me as if that chap ain’t fond of you, laughing at you like that,” said Schweik, while the desperate man sat down again beside him. “Those policemen are capable of anything when they’re in a wax. Just you sit down quietly if you don’t want to hang yourself, and see how things turn out.”

After a long time heavy steps could be heard in the passage, the key grated in the lock, the door opened and the police officer called Schweik.

“Excuse me,” said Schweik chivalrously, “I’ve only been here since twelve o’clock, but this gentleman’s been here since six o’clock this morning. And I’m not in any hurry.”

There was no reply to this, but the police officer’s powerful hand dragged Schweik into the corridor, and conveyed him upstairs in silence to the first floor.

In the second room a commissary of police was sitting at a table. He was a stout gentleman of good-natured appearance. He said to Schweik:

“So you’re Schweik, are you? And how did you get here?”

“As easy as winking,” replied Schweik. “I was brought here by a police officer because I objected to them chucking me out of the lunatic asylum without any lunch. What do they take me for, I’d like to know?”

“I’ll tell you what, Schweik,” said the commissary affably. “ There’s no reason why we should be cross with you here. Wouldn’t it be better if we sent you to the police headquarters?”

“You’re the master of the situation, as they say,” said Schweik contentedly. “From here to .the police head-quarters’d be quite a nice little evening stroll.”

“I’m glad to find that we see eye to eye in this,” said the commissary cheerfully. “You see how much better it is to talk things over, eh, Schweik?”

“It’s always a great pleasure to me to have a little confab with anyone,” replied Schweik. “I’ll never' forget your kindness to me, your worship, I promise you.”

With a deferential bow and accompanied by the police officer he went down to the guard room, and within a quarter of an hour Schweik could have been seen in the street under the escort of another police officer who was carrying under his arm a fat book inscribed in German: Arrestantenbuch.

At the corner of Spdlend Street Schweik and his escort met with a crowd of people who were jostling round a placard.

“That’s the Emperor’s proclamation to say that war’s been declared,” said the policeman to Schweik.

“I saw it coming,” said Schweik, “but in the asylum they don’t know anything about it yet, although they ought to have had it straight from the horse’s mouth, as you might say.”

“How do you mean?” asked the policeman.

“Because they’ve got a lot of army ofiBcers locked up there,” explained Schweik, and when they reached a fresh crowd jostling in front of the proclamation, Schweik shouted:

“Long live Franz Josef! We’ll win this war.”

Somebody from the enthusiastic crowd banged his hat over his ears and so, amid a regular concourse of people, the good soldier Schweik once more entered the portals of the police headquarters.

“We’re absolutely bound to win this war. Take my word for it, gentlemen,” and with these few remarks Schweik took his leave of the crowd which had been accompanying him.

CHAPTER VI – SCHWEIK HOME AGAIN AFTER HAVING BROKEN THE VICIOUS CIRCLE

Through the premises of the police headquarters was wafted the spirit of authority which had been ascertaining how far the people’s enthusiasm for the war actually went. With the exception of a few persons who did not disavow the fact that they were sons of the nation which was destined to bleed on behalf of interests entirely alien to it, the police headquarters harbored a magnificent collection of bureaucratic beasts of prey, the scope of whose minds did not extend beyond the jail and the gallows with which they could protect the existence of the warped laws.

During this process they treated their victims with a spiteful affability, weighing each word beforehand.

“I’m"extremely sorry,” said one of these beasts of prey with black and yellow stripes, when Schweik was brought before him, “that you’ve fallen into our hands again. We thought you’d turn over a new leaf, but we .were mistaken.”

Schweik mutely assented with a nod of the head and displayed so innocent a demeanour that the beast of prey gazed dubiously at him and said with emphasis:

“Take that idiotic expression off your face.”

But he immediately switched over to a courteous tone and continued:

“You may be quite certain that we very much dislike keeping you in custody, and I can assure you that in my opinion your guilt is not so very great, because in view of your weak intellect there can be no doubt that you have been led astray. Tell me, Mr. Schweik, who was it induced you to indulge in such silly tricks?”

Schweik coughed and said:

“Begging your pardon, sir, but I don’t know what silly tricks you mean.”

“Well, now, Mr. Schweik,” he said in an artificially paternal tone, “isn’t it a foolish trick to cause a crowd to collect, as the police officer who brought you here says you did, in front of the royal proclamation of war posted up at the street corner, and to incite the crowd by shouting: ‘Long live Franz Josef. We’ll win this war!*”

“I couldn’t stand by and do nothing,” declared Schweik, fixing his guiltless eyes upon his inquisitor’s face. “It fairly riled me to see them all reading the royal proclamation and not showing any signs that they was pleased about it. Nobody shouted hooray or called for three cheers — nothing at all, your worship. Anyone’d think it didn’t concern them a bit. So, being an old soldier of the 91st, I couldn’t stand it, and that’s why I shouted those remarks and I think that if you’d been in my place, you’d have done just the same as me. If there’s a war, it’s got to be won, and there’s got to be three cheers for the Emperor. Nobody’s going to talk me out of that.”

Quelled and contrite the beast of prey flinched from the gaze of Schweik, the guileless lamb, and plunging his eyes into official documents, he said:

“I thoroughly appreciate your enthusiasm, but I only wish it had been exhibited under other circumstances. You yourself know full well that you were brought here by a police officer, because a patriotic demonstration of such a kind might, and indeed, inevitably would be interpreted by the public as being ironical rather than serious.”

“When a man is being run in by a police officer,” replied Schweik, “it’s a critical moment in his life. But if a man even at such a moment don’t forget the right thing to do when there’s a war on, well, it strikes me that a man like that can’t be a bad sort after all.”

For a while they looked fixedly at each other.

“Go to blazes, Schweik,” said the jack-in-office at last, “and if you get brought here again, I’ll make no bones about it, but off you’ll go before a court-martial. Is that clear?”

But before he realized what was happening, Schweik had come up to him, had kissed his hand and said:

“God bless you for everything you’ve done. If you’d like a thoroughbred dog at any time, just you come to me. I’m a dog fancier.”

And so Schweik found himself again at liberty and on his way home.

He considered whether he ought not first of all to look in at The Flagon, and so it came about that he opened the door through which he had passed a short while ago in the company of Detective Bretschneider.

There was a deathlike stillness in the bar. A few customers were sitting there. They looked gloomy. Behind the bar sat the landlady, Mrs. Palivec, and stared dully at the beer handles.

“Well, here I am back again,” said Schweik gaily, “let’s have a glass of beer. Where’s Mr. Palivec? Is he home again, too?”

Instead of replying, Mrs. Palivec burst into tears, and, concentrating her unhappiness in a special emphasis which she gave to each word, she moaned:

“ They — gave — him — ten — years — a — week — ago.”

“Fancy that, now,” said Schweik. “Then he’s already served seven days of it.”

“He was that cautious,” wept Mrs. Palivec. “He himself always used to say so.”

The customers rose, paid for their drinks, and went out quietly. Schweik was left alone with Mrs. Palivec.

“And does Mr. Bretschneider still come here?” asked Schweik.

“He was here a few times,” replied the landlady. “He had one or two drinks and asked me who comes here, and he listened to what the customers were saying about a football match. Whenever they see him, they only talk about football matches.”

Schweik was just having a second glass of rum when Bretschneider came into the taproom. He glanced rapidly round the empty bar and sat down beside Schweik. Then he ordered some beer and waited for Schweik to say something.

“Oh, it’s you, is it?” said Schweik, shaking hands with him. “I didn’t recognize you at first. I’ve got a very bad memory for faces. The last time I saw you, as far as I remember, was in the office of the police headquarters. What have you been up to since then? Do you come here often?”

“I came here to-day on your account,” said Bretschneider. “They told me at the police headquarters that you’re a dog fancier. I’d like a good ratter or a terrier or something of that sort.”

“I can get that for you,” replied Schweik. “Do you want a thoroughbred or one from the street?”

“I think,” replied Bretschneider, “that I’d rather have a thoroughbred.”

“Wouldn’t you like a police dog?” asked Schweik. “One of those that gets on the scent in a jiffy and leads you to the scene of the crime?”

“I’d like a terrier,” said Bretschneider with composure, “a terrier that doesn’t bite.”

“Do you want a terrier without teeth, then?” asked Schweik.

“Perhaps I’d rather have a ratter,” announced Bretschneider with embarrassment. His knowledge of dogcraft was in its very infancy, and if he hadn’t received these particular instructions from the police headquarters, he’d never have bothered his head about dogs at all.

But his instructions were precise, clear and stringent. He was to make himself more closely acquainted with Schweik on the strength of his activities as a dog fancier, for which purpose he was authorized to select assistants and expend sums of money for the purchase of dogs.

“Ratters are of all different sizes,” said Schweik. “I know of two little ’uns and three big ’uns. You could nurse the whole five of ’em on your lap. I can strongly recommend them.”

“That might suit me,” announced Bretschneider, “and what would they cost?”

“That depends on the size,” replied Schweik. “It’s all a question of size. A ratter’s not like a calf. It’s the other way round with them. The smaller they are, the more they cost.”

“What I had in mind was some big ones to use as watch dogs,” replied Bretschneider, who was afraid he might encroach too far on his secret police funds.