3,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

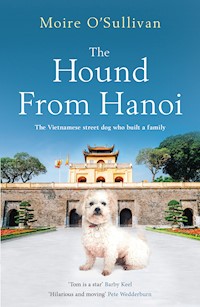

Tom is on the menu at a dog-meat restaurant in Hanoi when he is rescued by an Irish couple escaping economic woes back home. The three embark on a whirlwind tour of Vietnam, Nepal and Cambodia, determined to stay together against the odds.In this poignant tribute to her late husband Pete, Moire O'Sullivan recalls how their devotion to Tom helped forge a love between them that will last for ever.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Moire O’Sullivan is a mountain runner, adventure racer, outdoor instructor, author and mum. Moire previously worked throughout Africa and South-East Asia for international aid agencies. It was while living in Vietnam that she and her late husband Pete met Tom, the intrepid street dog. Moire now lives in Rostrevor, Northern Ireland with Tom and her two young children.

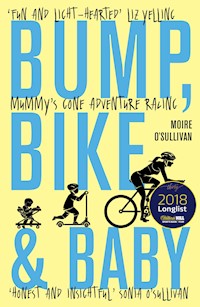

Also by Moire O’Sullivan

Bump, Bike & Baby

Mud,Sweat & Tears

First published in Great Britain by

Sandstone Press Ltd

Willow House

Stoneyfield Business Park

Inverness

IV2 7PA

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Moire O’Sullivan 2020

Editor: K.A. Farrell

The moral right of Moire O’Sullivan to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Sandstone Press is committed to a sustainable future. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

ISBN: 978-1-912240-58-6

ISBNe: 978-1-912240-59-3

Tom’s portrait © Sinead Murphy from Photography & The Dog

To my dear Pete

Rest inPeace

List of Illustrations

1. Tom the puppy after just arriving in our flat in Hanoi, Vietnam 2009

2. Reggie, Pete’s childhood sheepdog. Waterford, Ireland

3. Moire and Pete visiting Hạ Long Bay, Vietnam 2009

4. Pete with his beloved Tom, Vietnam 2009

5. Pete and his Honda Motorbike in Hanoi, Vietnam 2009

6. Pete and Moire hiking to Poon Hill on the Annapurna Circuit, Nepal 2010

7. One-year old Tom in his home in Kathmandu, Nepal 2010

8. Moire on a mountain run on Kathmandu’s ridge. Nepal 2010

9. Pete in Kathmandu’s Durbar Square, Nepal 2010

10. Pete and Moire in a traditional Cambodian outfit photoshoot, Phnom Penh 2011

11. Pete and his beloved Tom back home safely in Ireland, 2014

Contents

Prologue

1 – A New Home

2 – The Search

3 – The Perfect Hound

4 – Puppy Trouble

5 – Toilet Training

6 – Vietnamese Ladies

7 – New-Found Love

8 – Near-Death Experiences

9 – On the Move

10 – Kathmandu Chaos

11 – Tom’s Flight

12 – Himalayan Home

13 – Abandoned

14 – Reunited

15 – Bad Beginnings

16 – Tom’s Teething Pains

17 – If You Go Down to the Woods Today

18 – On the Move (Again)

19 – Decompression

20 – Tom’s Villa

21 – Teenage Tom

22 – Doggie Dates

23 – Should We Stay or Should We Go?

24 – Certificates and Signatures

25 – Homeward Bound

Prologue

Pete asked me to write this book.

‘Wouldn’t it be great to walk into a bookshop and see a picture of our dog on a paperback?’ he’d say.

I wasn’t convinced. I write about mountain running and adventure sports, not pets.

It didn’t take long for Pete to convince me, however, that our ‘Hound from Hanoi’ deserved to have his memoirs told. Our dog had travelled more places and lived through more hair-raising experiences than most humans we knew. There was definitely a story there.

I spent most of 2018 writing The Houndfrom Hanoi, each completed chapter being passed to Pete for his gentle nod of approval. It was only when I was doing the final edits on this book that Pete became unwell. It didn’t seem anything serious; just a piece of work that was stressing him out a little and making him lose sleep. We didn’t think much of it.

Unfortunately, Pete never showed any signs of recovery. Instead his worries continued to multiply, his insomnia spiralling out of control. Within months he was diagnosed with depression. He was put on a cocktail of medication and prescribed counselling sessions. Nothing seemed to work.

Then, on 27 December 2018, Pete took matters into his own hands. Unable to cope with his oppressive negative thoughts and feelings, he left the house early one morning and never came back. Mountain rescue found his body five hours later in the nearby forest where he would often run.

Nothing prepares you for the loss of a loved one, let alone to suicide. For the next few months I was in pure survival mode, bracing myself for the next raw emotion to batter me just when my guard was down.

While all of Pete’s loved ones were busy coming to terms with his death, the Hound from Hanoi manuscript lay in a file of my computer, untouched. I didn’t know what to do with it. It wasn’t until I considered what Pete would have wanted that I realised that I had to release it to the outside world.

Reading through these pages again after Pete’s untimely departure, it has struck me that this book is not just about our dog. Though I never intended it at the time of its writing, The Hound from Hanoi is a magnificent testament to Pete and to all that he loved in the world.

This book is also an appeal to those suffering from depression to please never give up hope. You may believe that the world would be better without you, but despite what this horrific illness might tell you, nothing could be further from the truth.

1

A New Home

Every dog needs a loving, stable home. Ten years ago, this was the one thing I didn’t have.

It was early 2009, and I was living in Dublin, witnessing the demise of the Celtic Tiger. Everywhere I turned, there was frightening talk of pay cuts and job losses, mortgage defaults and home seizures as the Irish property bubble burst.

‘There’s no point hanging around here with everyone so depressed,’ my boyfriend Pete told me on a near-daily basis. ‘I’m going to find myself a job somewhere else and get the hell out of here.’

When Pete said ‘somewhere else’, he didn’t mean some other Irish city. He didn’t consider taking the boat to England like emigrants of the 1970s escaping Ireland’s long-stagnant economy. He meant packing a single bag and jetting to the other side of the world as he had done before at the tender age of eighteen, fleeing Ireland for the United States. Twenty years on, Pete was intent on doing exactly the same again.

I was quickly learning that Pete didn’t do things by halves.

After just a few calls, he reconnected with an old friend in Vietnam, who needed someone just like Pete to work for him.

‘Come with me,’ Pete said to me after another one of my what-am-I-going-to-do breakdowns.

I hesitated. Vietnam seemed like a terribly long way to go just to find employment. What if I went all that way and still remained jobless, homeless and depressed? What if I missed Ireland too much and pined for its shores?

‘What have you got to lose?’ Pete said, sensing my reluctance. It was a valid question. Neither of us had borrowed copious amounts of money from the banks when they were desperately throwing cash around. Neither of us had property tying us to our country of birth. We had no children to care for, no pets to rehome. All we had was our redundancy money, which was just about enough to cover a plane ticket and a couple of weeks’ rent.

What I feared was that our relationship wouldn’t survive the drastic move. We had been together less than a year, taking advantage of the heedless days of Ireland’s boom, spending money on frivolous things, having tons of flirtatious fun. Yet, as a dating couple, we had still lived relatively separate lives. Relocating to Vietnam meant that a lot would have to change. I would see an awful lot more of Pete, and he of me, and I wasn’t sure whether we’d both like what we discovered. At the same time we would have to adapt to another culture, language and lifestyle. How would we cope if one of us loved Vietnam, and the other one felt only homesick?

‘I’ll give it six months,’ I said to Pete, after going over in my mind ad nauseam all the pros and cons. Even if it didn’t work out, at least I could consider it an adventure, to explore a part of the world that I had never been to before.

Pete looked visibly relieved when I finally gave him my answer. ‘Great,’ he said. ‘Let’s book return flights, and if it’s not working out by, say Christmas . . . well, I suppose we’ll see.’

Six months. That gave us just enough time to cast our fledgling relationship into the Vietnamese waters and see if it would sink or swim.

So we moved to Vietnam. After a month in our new home of Hanoi, much to my surprise, our relationship seemed to be bobbing along. We had found a beautiful open-plan apartment overlooking the city’s Trúc Bạch Lake. Pete’s new job was interesting, and lucrative enough to sustain us both while I continued my search for work. More importantly, the country was thriving. There was investment, growth, employment and construction, a sharp contract to the bleak Ireland we had fled.

As I sat sipping chilled Chardonnay on the balcony overlooking our new city, I gazed across at Pete opposite me, reclining on a bamboo chair with a matching glass in his hand.

‘More wine?’ he said, catching my wandering eye. I nodded, silent and content. Maybe hanging out in Hanoi wasn’t as bad as I had originally thought.

‘What do you fancy for dinner?’ I said, after an unexpected tummy rumble. ‘I could cook if you like.’ Pete shrugged his shoulders, easy enough with the idea. ‘I saw a market at the end of the street and was hoping to check it out,’ I continued. ‘Maybe I could pick up some ingredients there for, I don’t know, a stir-fry?’

‘Sure,’ Pete said. ‘Do you need a hand?’

I shook my head as I readied myself to leave. I wanted Pete to stay and enjoy the sunset. He had done enough for me already, bringing me to this amazing place.

Leaving the serenity of our apartment, I braced myself as I descended the stairs to the road below. Opening the front door, I was immediately hit by the torrent of traffic that is Hanoi’s transportation network. Buses, lorries, motorbikes, rickshaws, cars and cabs flooded past me, a wall of rubber, metal and fumes barring my passage to the other side. I stood there, mesmerised by the mania. It took a split second before I remembered the market I planned to visit was located on the same side of the street as our apartment.

I turned, having received a momentary reprieve. I knew that one day I would have to learn to traverse a Hanoian street, but for the moment I was happy to watch this traffic turmoil as a tourist from the safety of the pavement.

A five-minute walk transported me to the market’s gates. Once inside its confines, the smell of rotting produce bombarded me straightaway, stifling sickly-sweet gases entrapped under its sun-scorched tarpaulin roof. The noise of boisterous food vendors heckling prospective buyers quickly replaced the deafening din of the road users outside. Flustered, I vowed to make my purchases quickly and to retreat as soon as I could back to the sanctity of our flat.

Meat and vegetables were the sole items on my shopping list. I spotted the butcher’s stall in front of me and headed straight for it.

As soon as I got within striking distance, I stopped dead in my tracks. Starring hard at the fly-infested corpses strewn across the butcher’s wooden blood-stained table, I tried to convince myself otherwise but no, it was a dog all right. The sharp teeth protruding from its head were undeniably canine. The body’s dimensions were those of a small domestic pet. It was just that I didn’t expect to see ‘dead dog’ on display on that day’s specials list.

The way the body was positioned made it look oddly at peace. It was lying on its back, with all four of its legs dangling in the air, paws bent. If it had been still alive, it would have been an invitation to me to approach the bench and rub its furry belly. A scratch on this dog’s stomach, however, would have drawn no looks of adoration from it, no licks of unending affection. The dog was as rigid as a plank, riddled with rigor mortis.

There was not even a patch of fur on this animal for me to stroke. The butcher had skilfully stripped the poor doggie of its entire coat, leaving behind a shiny, leathery skin. Even its snuggly ears and soft waggly tail had been relegated to the bin. I couldn’t help but see my own beloved childhood canines lying there lifeless on that table, and immediately felt faint.

Coming to my senses, I realised that the butcher was watching me, intently. Slowly, he took his cleaver and gestured to the canine carcase, snarling a toothless grin.

‘No,’ I said. ‘God, no.’

But the butcher could not understand me, and seemed intent on making a sale.

I shook my head profusely, backing away from his stall while contorting my face in disgust. Surely such body language was universally understood, even here in Asia. The butcher fixed his eyes on me as I reversed quickly away, disappointed that I didn’t fancy serving up a leg of dead dog for dinner that night.

I made a hasty retreat in the direction of the nearest vegetable stall. There I browsed its exotic fare, trying all the while to erase from my mind the image of the dead dog. The abundant variety of fresh fruit and vegetables would have made anyone happily forgo meat. I quickly filled my shopping bag with water spinach, bamboo shoots and bitter melon, before making eye contact with the vegetable vendor.

‘Bao nhiêu?’ I said, with a confidence that took me by surprise. Miss Phuong, our new Vietnamese teacher, would have been proud of my latest vocabulary advances. My grasp of the local language, however, stopped there. The lady shouted a sentence at me that bore no resemblance to any I had learned thus far. Not wanting to lose face, I stuffed a fistful of dong notes into the seller’s hand and hoped she would give me back some change.

I glanced over my shoulder to the butcher, who had apparently lost all interest in me. Instead he was busy carving up some canine fillets for an eager customer who had just arrived at his stall. I had wanted to buy some pork for the stir-fry I had promised Pete, but didn’t dare approach his counter, still littered with animal figurines, again. I was too scared I might offend this knife-laden butcher by refusing his local dog delicacy. If there was one thing I had already learned in this country, it was that you don’t want to offend the Vietnamese, even accidentally.

I walked the short distance from the market back to our apartment block and climbed the four flights of stairs to our flat. Catching my breath, I slid open the front door and threw my shoes inside the entrance. Dropping my market purchases in the kitchen, I spied Pete through the glass doors, still sitting on the balcony. I hesitated to go outside to him, back out into the hot, humid weather that I had just escaped. Pete had left the air-con on inside, and our home was wonderfully cold and sterile. It was the perfect antidote for the humid walk, oppressive traffic and putrid market smells that still inundated my senses.

I was so traumatised by my dead-dog encounter, however, that I had no choice but to join Pete on the balcony. I pushed open the glass door and was instantly hit by the clammy heat I had tried so hard to avoid.

‘Hey there, what’s up?’ Pete said. ‘Did you get everything you need?’

‘Did you know they eat dogs here?’ I said, answering neither of his questions.

‘I thought they only did that in China,’ Pete replied, slowly placing his wine glass back on the table. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘The feckin’ butcher at the market,’ I said, no longer able to hide my distress. ‘He just tried to sell me dog steaks.’

I yanked my chair back out from under the table and threw myself into it. Without asking, Pete poured a glass of wine and pushed it in my direction. He had begun to recognise my look when I desperately needed alcohol.

‘Have you eaten dog?’ I asked, unsure if I wanted to know. I did know that Pete had lived in China for a while in his twenties, so there must have been times when dog was served up on the menu.

‘God no,’ Pete replied, nearly choking on his drink at the mere mention. ‘I like my dogs alive.’

I clinked my glass against his, congratulating him on the right answer. I had still a lot of things to learn about my boyfriend.

‘I thought dog meat was meant to give men strength, vigour and virility?’ I said cheekily, the wine quickly loosening my tongue. ‘Surely you’d like a bit of that? I can always go back to the butcher and buy some if you like.’

Pete appeared to contemplate my offer for a moment, then thankfully declined. He probably thought he already had enough of those qualities, so had no need of a top-up via some canine dining.

‘Why don’t we just sit here and enjoy our wine instead?’ he said. ‘Then maybe I can help you rustle up that stir-fry you were suggesting?’

The mere mention of my ill-advised cooking plan unexpectedly made my stomach lurch. ‘Ah, would it be okay if we eat out instead? I’m sure those vegetables I got will last until tomorrow.’ I also planned to get some pre-packaged frozen meat from the relative safety of the nearby supermarket the following day. ‘What about some street food?’ I added, as Pete downed the dregs of his glass.

He hesitated.

‘Come on, it’ll be fun.’

‘Fun getting food poisoning?’ he replied. ‘No thanks.’

‘Seriously Pete, I’m sure it’s perfectly safe,’ I said, surprised that I was now the adventurous one. ‘Why don’t we go downstairs and try out the hot-pot stalls below the flat? If we don’t like it, we can always go to a proper restaurant further on down the road.’

I had secretly wanted to try Vietnamese hot-pot ever since we had arrived. Every evening, like clockwork, Vietnamese hot-pot ladies arrived en masse outside our home laden down with utensils. They would first set about meticulously sweeping and scrubbing the pavements, before throwing down gigantic woven mats on the sparklingly clean slabs. On top of these, they set knee-high tables and tiny plastic stools, the type typically used in Irish playschools. The tables were then set with a simple gas-burning cooker, surrounded by plastic bowls and chopsticks.

I had watched hungry Vietnamese labourers pass these hot-pot ladies at the end of the day and murmur their deepest dinner desires. These workers would then take a seat at the low-level tables and wait for food to materialise. From out of nowhere, I had seen plates of thinly sliced raw meat and fish conjured up, together with a dazzling array of vegetables. These were placed on the table in front of the ravenous customers, together with a saucepan of steaming stock. Into this cauldron the diners themselves threw the uncooked morsels for them to be boiled. Then, at their own leisure, the diners picked out their freshly cooked meat and veg, and gobbled the whole thing up.

After some persuasion, Pete reluctantly agreed to my dinner suggestion and we made our way down to the street. By then the torrent of daytime traffic had subsided to a trickle, and Pete was able to shepherd me safely across the tarmac to the lakeside dining area.

The first obstacle Pete faced was making himself comfortable on the miniature plastic stool. It soon became obvious that they had not been designed with six-foot Caucasian males in mind. The Vietnamese were not only smaller in stature than Pete, but infinitely more flexible. After several aborted attempts at squatting without tipping over, Pete threw the toy chair to one side, sitting instead awkwardly cross-legged on the mat. Instead of a calm yogi pose, he looked distinctly squashed and grumpy. It was not a good start to our dinner date.

‘So how do we go about getting some food around here?’ Pete said, hoping his raised voice would attract someone’s attention. I silently looked around to see if I could spot a hot-pot lady who might come and take our order.

We didn’t have to wait long before one arrived tableside. She said something in quick Vietnamese that neither of us understood.

‘Ah, menu?’ Pete said, tracing a square in the air with his fingertip.

Instead of a piece of paper, his request was met with a further onslaught of local lingo.

‘This is hopeless,’ Pete said, rapidly losing patience. As he struggled to stand up to leave, I desperately tried to remember some vocabulary from the weekly Vietnamese language lessons we’d been taking. I don’t give up that easily.

‘Thịt bò?’ I said, imploring her to understand.

‘Vâng,’ she replied, before marching away from us back to her makeshift kitchen on the roadside.

‘What did you just say?’ Pete asked me when she was out of earshot, unsure if he should settle himself back down again.

‘I just said, “beef.” That’s all,’ I replied. ‘It seems to have done the job, no?’

‘As long as she doesn’t think we ordered raw dog, I really don’t mind what she brings,’ Pete said. ‘I’m starving.’

‘Don’t remind me of that poor animal,’ I implored.

‘I’m sorry,’ Pete said. ‘It’s just that all this talk of dead dogs reminds me of my poor Reggie.’

‘Reggie?’ This was the first time I had heard Pete mention the name.

‘My dog, when I was a teenager,’ Pete said. ‘He died when I was at university.’

‘That was over twenty years ago,’ I said, surprised that he’d still be upset by a dog’s death nearly two decades on. I’d also had dogs when growing up, but my parents had taught me to handle their demise stoically.

‘Yeah, but he was the best dog ever!’ Pete proclaimed, just as the hot-pot lady emerged from the shadows, carrying a pot of piping hot stock. She proceeded to place it carefully between us on the gas burner before scurrying away to retrieve the rest of our order. The aromatic steam spiralled upwards, moistening Pete’s cheeks ever so slightly.

‘My Dad brought home this pup one day,’ Pete started to explain. ‘He was meant to be just a family dog. But, seeing that we lived on a farm, Reggie was soon put to work.’

I was always on a mission to find out more about my boyfriend, and this canine conversation had started him down a road I was happy to follow. ‘Did Reggie herd sheep?’ I asked, knowing that many rural Irish farms keep such flocks.

‘No – we had a dairy farm, and my Dad also planted wheat,’ Pete said. ‘Da would send Reggie and me out to the fields to pick stones out of the ground so they didn’t catch in the harvesting machinery.’

‘I’m sure the dog was a great help moving rocks,’ I said, with obvious sarcasm.

‘He was!’ Pete said, practically jumping out of his yogi pose, oblivious to my attempt at humour. ‘Reggie was the best company ever for stone-picking.’

The hot-pot lady returned and covered our kiddy table with produce, briefly interrupting our discussion. I carefully picked up a pair of chopsticks, intending to skilfully use them to pick and place the food she had given us into the boiling stock. Instead I fumbled with them, dropped them, then gave up entirely, opting instead to up-end the entire contents of various plates straight into the pot.

Despite nearly four weeks of practice, I had zero dexterity when it came to these wooden tools. Fortunately, Pete was seemingly too caught up in resurrected thoughts of his deceased dog to register my chopstick uselessness.

‘I was sent to boarding school when I was a teenager and I had to leave Reggie at home,’ Pete continued. ‘One day, my Mum phoned and asked how I was doing, if I missed anyone at home.’

‘And you said?’

‘I think she wanted me to say that I missed her terribly and that I desperately wanted to come back to the farm,’ Pete said. ‘But all I did was break down and blurt out, “I really miss Reggie”. I don’t think my mother ever forgave me for choosing my dog over her.’

I picked up my chopsticks again, determined they would not defeat me. Anchoring them together, I pivoted the top one and made a stab at the food floating on the pot’s surface. Borderline starvation rendered me successful. I pinched out strands of meat and spinach leaves, and divided them out between us. We then slurped up the contents of our bowls and emptied them within seconds.

‘So why don’t we get a dog?’ I said, surprising myself with the question.

‘You’re not serious,’ Pete said.

Pete was right, it was a ridiculous idea. Vietnam was still so new to both of us, I had yet to find a job and neither of us knew how long, or even if, our own relationship would last. Still, something felt so right about my suggestion. Maybe I craved a sense of stability, something I thought a dog could provide. On reflection, I was probably more like a crazed woman desperate for a child, certain the arrival of an infant would make her present life better.

‘Why not?’ I replied, before cautiously adding, ‘sure we’ll probably be staying here for a while?’

Much to my chagrin, Pete refused to confirm or deny our future whereabouts.

‘Then again,’ I said, changing tack, ‘maybe we could help save one of those beasts from that mad butcher’s knife at the market.’

Secretly, I missed having an animal companion of my own. I had craved a pet when I lived in Dublin, but had travelled too much for work to actually take care of one.

‘No, it’s not that,’ Pete said, looking around for the hot-pot lady so that we could get the bill and hightail it out of there. ‘I couldn’t have another dog after Reggie. It would be . . . disloyal.’

I was taken aback; I had never heard Pete being so sentimental.

‘Let me keep an eye out at least,’ I said, ignoring what Pete had just said. ‘If I find a dog that’s suitable, maybe we could have a quick look? Well, what do you think?’

2

The Search

Despite Pete’s reluctance, I resolved to find us a dog. I didn’t want to fork out cash, however, because of my diminishing bank balance; I wanted one going for free who would appreciate a good home.

I soon realised my search couldn’t be for just any dog. Living in an apartment, up four flights of stairs, meant we could only accommodate one relatively small in size.

I started asking around everyone I knew, but finding a dog alive and well in Hanoi is easier said than done. In desperation, I logged on to the website that all expats turn to when negotiating the various peculiarities of living in Hanoi: The New Hanoian is the one-stop shop for everything expats need to know, acquire or share. Via this site, we had procured crockery, located a flat, joined a running club and found a Vietnamese language teacher. As we’d sourced such a disparate array of objects on the New Hanoian already, I figured that it must be the place to locate one lonely, Vietnamese puppy.

I scanned the classifieds section for any dog-related ads. I saw all manner of items for sale – everything from Honda motorbikes to fish tanks to second-hand yoghurt makers. I purposefully ignored the dodgy notices from lonely men and women looking for ‘good massages’ and ‘cuddle buddies’. I occasionally clicked on house-moving adverts, to see if a dog was also part of the clear-out deal. All too soon, however, I found I could scroll down the list no more. Dogs were not given the slightest mention despite hundreds of items listed.

Obviously the hounds of Hanoi were all happily housed, or had already been served up on a succulent platter. Even when I posted an advert explicitly labelled, ‘Wanted: Dog’, I failed to receive a single answer. My hound had evidently yet to learn how to turn on a computer and log on.

While my search for a canine companion reached an unforeseen impasse, Pete and I turned our attention to a more pressing concern. We were spending a small fortune on taxis to get around Hanoi’s expansiveness. Pete came home one day from work, his wallet devoid of Vietnamese dong for the umpteenth time.

‘We need to get a motorbike,’ he said as soon as he came through the door.

‘Motorbike? Do you even know how to drive one of those things?’ I replied, drying my hands on a dishcloth after washing up our respective two bowls and plates. I made a mental note to go back to the New Hanoian and find us some more kitchenware.

‘Kinda,’ he said. ‘Someone always had a motorbike knocking about on the farm when I was young. Actually, me and my mate Denny used to bomb around on back roads on his dirt bike. I’m sure the motorbikes here are just like the ones at home.’

I turned back to the sink and the dishes to hide from Pete my look of horror. I wanted to tell him not to be so stupid, that motorbikes are really dangerous, but I didn’t want to make the classic mistake of telling my man what to do.

‘Where would you even get a motorbike anyway?’ I asked, concealing the fact that I’d already seen hundreds for sale on the expat website.

‘The guys at work said you can hire them for like fifty US dollars a month,’ Pete replied. ‘The only thing is, I need to get a license first.’

‘How do you get one of those?’ I asked, turning around to see Pete shrugging his shoulders.

‘Seeing that I’m at work all week,’ Pete said, cringing ever so slightly, ‘I was hoping you could figure that one out.’

The whole idea of riding a motorbike filled me with inexplicable dread. I felt I was being forced to work out how to procure a license for something I didn’t want either of us to have permission to drive. However, I did accept that having a motorbike was probably the best way to get around Hanoi. All the Vietnamese seemed to have one, even tiny pretty girls who seemed far too dainty to be wearing a crash helmet and revving a throttle at traffic lights. If they could drive one, I figured that burly Pete and I could as well.

Pete found out from his colleagues the documentation we needed. Once I managed to get it all together, I made my way bright and early the following morning to the driver licensing office in downtown Hanoi. I entered the building and joined a queue, the only white girl in a long line of Asian commuters.

When I arrived at the counter, I presented the lady behind the glass with our paperwork. I gave her completed application forms, together with originals, copies and translations of our passports and Irish driving licenses. But instead of the lady accepting my paper offering with serenity and calmness, it was received with bitter consternation. She started to point angrily at various sections on the form while spitting rapid-fire Vietnamese.

My statement of ‘I just would like some motorbike licenses for myself and Pete, please,’ was met with even more irate words beyond my comprehension. I looked at the growing line of drivers behind me, fearing this could, if I wasn’t careful, descend into an international incident.

Quickly, I dug out my phone and called Ms Phuong, my Vietnamese teacher, who would surely understand what the hell was going on. As soon as I connected, I thrust my phone in the direction of the administrator. Ms Phuong had barely the chance to introduce herself before she also received an earful of abuse. Once the lady had finished with Ms Phuong, she shoved the phone back into my face. I held up the earpiece to hear the shaky voice of my Vietnamese teacher on the other end.

‘You have brought your application to the wrong office,’ Ms Phuong whimpered. ‘You are at the driving test centre. What the lady has been trying to tell you is that you must instead exchange your Irish licenses for Vietnamese licenses, not get new ones. For that you need different forms and you need to go to another office on the other side of town.’

I thanked Ms Phuong for her intervention, forced an apologetic smile at the administrator, and slunk my way back out on to the street. Opening the door, the full heat of Hanoi hit me with a vengeance.

Though Ms Phuong had really tried to help me back there, I felt that the majority of Vietnamese were more like the administrator, unwilling to welcome foreigners into their country. Even though I liked Vietnam, I was beginning to get the impression that I wasn’t really wanted there.

After a stressful taxi ride across town, I finally located the correct office where the exchange process could take place. I was not in the door five minutes, however, when I was sent straight home with a different form that needed filling in. The following day, I marched back to the same place with every piece of paper possible, stamped with every insignia imaginable. The clerk flicked through my file of official documentation, slowly nodding his head. I allowed myself to think the impossible: that Pete and I might actually get Vietnamese driving licenses that day.

‘Photo too big,’ the clerk said, handing me back my file.

‘What?’ I said.

‘Too big,’ he said, pointing vigorously to the universally accepted passport-sized picture that I had taken back in Ireland. ‘Need small.’ He seemed satisfied with Pete’s photos, which he had had specially taken at his Hanoi workplace. Pete’s application was good to go, while mine was unfortunately rejected.

‘But where?’ I said, terribly close to dropping to my knees to beg him to change his mind.

‘Photo shop,’ he said, stating the obvious before diverting his attention to the customer standing behind me. Our conversation, as far as he was concerned, was done.

I staggered out of the office, about to scream with rage. Then I came to my senses: having an angry-looking mug shot on my driving license wouldn’t be wise if a Vietnamese cop ever stopped me at a later date. I put on my most serene expression, and went searching for a ‘photo shop.’

I accidentally visited a pharmacy, then a bakery, before finally stumbling randomly across a small Kodak processing store. Through an intricate mixture of hand-signals and jumbled-up vocabulary, I managed to explain to the shop attendant that I needed my photo taken for a driving license. He took the shot, then emailed it somewhere. Thirty minutes later, a man pulled up on a motorbike, photos in his hand. He gave them to me. I took one look and handed them straight back.

‘Not me,’ I said, cursing myself for thinking that something as simple as getting some passport photos would happen without a hitch in this country.

The man took a look, shook his head, and pushed them back in my direction. At his insistence, I took a second look.

‘You’re not serious,’ I whispered, as I absorbed my Vietnamese version. I no longer had brown hair, but instead what appeared to be a jet-black mane. My skin had become as flawless as Ms Phuong’s, with a slightly browner tone. The developers didn’t know what to do with my blue eyes, having never encountered an iris that wasn’t brown. Instead, in the photo, they had made them a piercing shade of blue, straight out of a Disney film.

I stuffed some money into his hand and glanced quickly at my watch. It was 10.20 a.m. For some inexplicable reason, the office closed at 10.30 a.m. I hadn’t a second to lose. I bolted out of the shop, ploughing into pedestrians and street-vendors unfortunate enough to impede my way. To get to the photo shop I had originally crossed the street via a considerable detour, using a set of traffic lights that vehicles actually obeyed. If I was going to make it before the office closed, such an elaborate diversion was no longer feasible.

I had no option but to run the gauntlet and dash straight across the street. Miraculously, as if I were Moses himself parting the Red Sea, the motorbikes swerved to the left and right of me. In a moment of sheer desperation, after weeks of unsuccessful attempts, I had finally learned to properly cross a congested Vietnamese street.

At 10.26 a.m., I burst through the office doors, dripping in nervous sweat. I pushed my way through to the clerk who had earlier rejected me, and proudly presented him with my slightly smaller, made-in-Vietnam photos. My application was complete.

When I arrived home, Pete was overjoyed to hear that we would soon be the proud owners of brand-new Vietnamese driving licenses. I was unable to share in his excitement after the rigmarole I’d just been through, so while he went off to find a motorbike for hire, I logged back on to the New Hanoian to find myself a normal pedal bicycle.

Back in Ireland, I had ridden my bicycle everywhere. If it was good enough for me at home, I reasoned, it would do me just fine in Hanoi. Despite the licenses arriving a few days later, I refused to ever make use of mine. To this day in fact, I still have no idea how to drive a motorbike. Anyhow, the Vietnamese used regular pedal bikes for years before all those new-fangled motorised Hondas ever came along.

I scrolled down the website’s classifieds to see if there were any bicycles for sale. I dared not raise my expectations, given the random junk people always seemed to post up, but soon glanced across a new ad that stopped my mouse-finger dead in its track. Not a bicycle, but a ‘Schnoodle, going to a good home’.

Schnoodle? What the hell is that?

Out of curiosity, I opened a new window and typed ‘Schnoodle’ into the browser. My screen instantly filled with pictures of cute, little puppies. A schnoodle is a type of dog, a cross between a schnauzer and a poodle, and this one was looking to move house. My hound had finally worked out how to get in contact.

I hit reply to the advert immediately and told its author that I was very interested indeed. They soon emailed back with a phone number and address, telling me to contact them if I wanted to visit said schnoodle.

Pete soon arrived home with his brand-new hired motorbike. He didn’t have time, however, to show me his latest wheels.

‘Pete, I’ve found a dog!’ I said. ‘Come look!’ I shoved my laptop right under his nose, the cutest picture I could find of a schnoodle dog emblazoned across its display.

‘That’s nice,’ Pete said, flopping down on the sofa. ‘But it’s not Reggie.’ He handed me back my computer.

‘You’re not going to find a replica sheepdog like Reggie out here in Vietnam, you know,’ I said, slightly exasperated.

‘Why are you so set on getting a pet anyway?’ Pete asked. ‘I really don’t understand.’

It was a good question. Like Pete, I was also brought up with pets around. Although we’d had dogs, my first pets were primarily of a feline kind. When I was six months old, my eldest brother dragged home a stray cat. She landed on all four proverbial feet as soon as she hit our doorstep. It wasn’t long before the creature was christened ‘Mother Cat’ as she popped out a litter of four. My parents let us keep the entire brood, upon which we bestowed the illustrious names of Eeny, Meeny, Miny and Moe.

We worked out that Moe was a female when she too started reproducing. My siblings and I were of course overjoyed with these additional playmates, and we set about naming them in earnest. The obvious solution was to call each of these brown and white kittens after our favourite chocolates, so we ended up having a plethora of cats called Yorkie, Milky Way, Smarties and Maltesers.

After seven years of multiplying moggies, my parents wisely decided to move house. Eeny and Yorkie, now safely neutered, were the only ones allowed to come with us. The rest were rehoused or ran away, depending on how smart or wild they were.

I knew that getting a cat now would be completely out of the question: Pete only had to sniff a cat’s hair from fifty paces to descend into a sneezing frenzy. He is so allergic he can barely sit in a room that a cat frequents before he has to make a hasty retreat to swallow some anti-histamines. Fortunately for Pete, although I was an established cat-lover from my early years, as a teenager I defected to the other side.